January 21, 2025

My Good Bright Wolf, by Sarah Moss

“You both had to live in a time and a place where people or at least women didn’t like themselves, or if they did, concealed their self-esteem with rigour.” —Sarah Moss, My Good Bright Wolf

My Good Bright Wolf, a memoir by Sarah Moss—the author of odd spare novels I’ve loved lately like Ghost Wall, Summerwater, and The Fell—is the kind of book that I keep talking about, and when I do, I’m served with the inevitable question, “What’s it about?” A question whose simple answer is that this is a memoir about anorexia, about how Moss’s eating disorder was born from a childhood of some depravity and would flare up again during the pandemic when she was in her mid-40s. A description that sounds interesting enough, though I confess I’d be unlikely to pick up such a book on those merits, and I only picked it up at all because Sarah Moss has become a must-read author for me, the kind of author whose books are never be “about” anything quite so straightforwardly as that.

Because her memoir is also about childhood, about being the child of parents who carry their own trauma, about the inheritance of pain, about how girls are taught to hate their unruly bodies and their unruly minds. It’s about escaping into books, and what she learned about life (and care and food and eating!) from Beatrix Potter’s tales, from Jane Eyre, Swallows and Amazons, Laura Ingalls Wilder, Little Women, Virginia Woolf, Mary Wollstonecraft, and more. It’s about growing up in a culture where you might have never met a woman who wasn’t suffering a diet, who ate what she wanted to, who didn’t hate her body, who had ever managed to be enough or not too much.

It’s a memoir about memory too, most of it written in the second person, the narration interspersed with commentary in italics by a character whose voice might well be that of the narrator’s mother, ever critiquing, undermining, suggestion it wasn’t bad as all that, that the problem was the narrator, all stories and her lies. Via these interjections and elsewhere, the narrator is hard on herself, though I admit I double down on that at times as a reader, the more contemporary parts of the memoir demonstrating the impossible mindset of someone with anorexia who refuses to relinquish their sense of control, making choices that put their life in peril. From the outside, the problem looks easy to fix, but Moss shows that the reality is much more complicated.

This is a very thoughtful memoir, a memoir about anorexia that even seems to avoid fat-phobia (the author lists Aubrey Gordon’s What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat and the podcast “Maintenance Phase” among the lists of resources), and anyone who ever had a female body or struggled with mental illness will relate to Moss’s story.

And anyone who doesn’t will still be enchanted all the same by the power of Moss’s writing and the rigorous thinking that is its underpinnings.

January 20, 2025

Showing Up

I showed up like this eight years ago, and I’m not sorry I did, but there was a whole lot I still had yet to understand about the moment I was trying to meet. Which I really did think was just a moment, one grand obstacle to be overcome, I was so utterly convinced of my righteousness, and it felt like a grand performance, utterly infused with ego: LOOK AT ME ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF HISTORY. And I wasn’t wrong about that, necessarily, but my grasp of the shape of history definitely left something to be desired. I kept thinking, “LOOK, HOW THERE ARE MORE OF US THAN YOU!” but I have come to doubt if this is a particularly good argument, especially when a convoy of people who definitely don’t share my principles tried a similar tactic in 2022, albeit with violence, implicit and otherwise. Which made me think that maybe it’s a slippery slope in which I do not want to participate, and wonder what better ways there might be to rise up in opposition.

Anand Giridharadas writes: “The first Trump presidency was a time of great and often smug certitude. He was so wrong that the contrast made us right. He was so against democracy and justice and freedom that anything we did was self-evidently heavenly. But self-righteousness corrodes the soul and the mind. And the long posture of resistance and fury and perma-vigilance has turned many of us into certitude bots instead of people of curiosity. Democracy is all about curiosity, it depends on curiosity, because it is about you and I figuring each other out and then choosing the future together, instead of the king doing it for us. But the moral clarity triggered by Trump’s vacuous viciousness lulled many of us into a dogmatic slumber. Now I see and hear around me people who are getting into a posture of real rethinking, who are returning to curiosity, who are willing to ask real and hard questions about what many of us missed and didn’t see and may not see still. Their posture is not outward but inward.”

Today, I don’t have any answers. I don’t even have a placard, but what I do have is a conversation with Heather Marshall about her 2022 bestselling novel LOOKING FOR JANE, which keeps on showing up on the bestseller list after all this time, its themes of reproductive justice and bodily autonomy continuing to resonate. The conversation is for paid subscribers on my Substack page, but the preview is available for everybody is and it’s worth checking out. Listen here!

January 13, 2025

Like Mother, Like Mother, by Susan Rieger

Admittedly, it’s an odd book, Susan Rieger’s third novel, Like Mother, Like Mother, told almost entirely through through expository dialogue by characters who talk like people in golden age film, the protagonist dead in the opening sentence—”Lila Pereira died on the front page of The Washington Globe.” I wasn’t sure in the opening chapters that the writer would be able to pull this off at all, but soon I was in the thrall of Rieger’s rigorous prose and compelled by its energy, and the Ephron-esque punch punch punch of this story, which is an ode to the knots and tangles of family ties and also to the culture of journalism.

Lila Pereira may be dead, but Rieger resurrects her immediately to show her style, unique, brutal and awesome at once. When she was two, her mother had been taken taken away to die in an insane asylum, her children left to fend with their abusive father. Lila decides that she’d be just as ineffectual as a mother herself, and only consents to have children when she falls in love with and marries Joe Maier, who she knows will be a perfectly good mother himself and accepts her otherwise refusal of the maternal role. Which sounds good in theory, but Grace, their youngest daughter, resents her mother’s devotion to her work and absence from home, writing her pain into a roman a clef about a monstrous mother, which backfires when Lila dies not long after publication and Grace looks awfully unsympathetic.

After her mother’s death, Grace takes on the job of finding out what really happened to Lila’s mother all those years ago, using her own journalistic chops (not far from the tree) to uncover the mystery, and everything that happens after that is a pleasure to behold.

January 13, 2025

Ways To Read More in 2025

I’m of two minds about this post. First, I am allergic to the ways in which online writing has become so prescriptive, which means that online reading has become about emphasizing the ways in which we’re all doing it wrong and are in need of optimization. This is everything I’ve been turning away from as a writer and a reader, and what I’m abjectly refusing for this new year. If all this striving was turning us into happy and satisfied beings, I’d be okay with it, but it’s not. (A book I read last year that clarified this was Meditations for Mortals.)

HOWEVER (and this is self-serving as someone who earns a living from books and publishing and also dreams of a world in which literature occupies as much cultural attention as reality television) aspiring to read more is a resolution that’s different from trying to lose 15 lbs, develop an entirely different personality, or make a fortune in a multi-level marketing scheme. I also think it’s an aspiration that, if you’re realistic, fair and easy on yourself, really can make you a little bit better off.

Further, I read 214 books last year, which is more books in a year than I’ve ever read in my life, so I know what I’m talking about. And I’m sharing the number 214 because having read so many books in a year is actually the single most impressive thing about me; I don’t run marathons, I don’t have pretty fingernails, I last won a literary prize 20 years ago for a story that was terrible—so please just let me have this one thing. If your own reading goal ever seems paltry compared to mine, remember that comparison is the thief of joy and you do you… but how about doing you with a just a little bit more time for reading?

Here are my tips for how to find some.

1) Get Your Blood Checked

This was a game changer for me! I went to donate blood last January and was refused because my iron count was too low, which was not surprising since I’d spent the last six months (during which I was otherwise well) struggling to get out of bed in the morning, feeling very much like a hibernating bear. So I started taking iron supplements (Floradix, the vegetarian variety that doesn’t cause digestive issues) and waking up an hour earlier (um, not too early—I will never been an early riser) and I decided to spend this bonus time not getting out of my cozy bed, but picking up the book on my bedside instead. Which is so much time for reading, not to mention a really lovely way to start each day.

And so if you, like me, are not particularly youthful, and you’re one of those people whose eyes fall down every time you curl up with a book, getting bloodwork done might be something to consider.

2) Put Your Phone (Far) Away and Delete Socials

It’s much easier to wake up in the morning and pick up a book if your smartphone is out of reach. Mine charges overnight far away from my bedside, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I’ve also deleted the only social media app (Instragram!) that had remained on my phone, which has freed up so much space in my mind and hours in my day. I still use social media on my desktop, and download Instagram once or twice a week to post and share other people’s posts in my stories (which I can’t do on the desktop) but I delete the app once I’ve finished.

And yes, it means I’m a little less connecting to the quotidian details of the 3000+ people I follow on Instagram, but maybe that’s okay…?

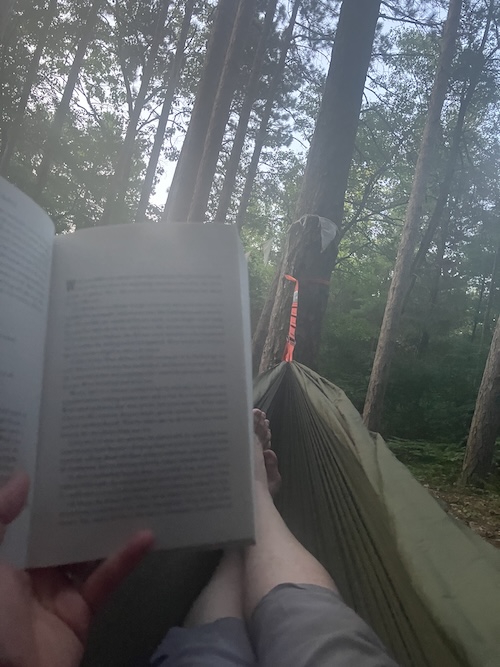

3) Find Your Desert Islands

Once your phone is out of reach, you’re on your way. I like to find opportunities to be stranded someplace with a book and nothing else for distraction. The bathtub is my favourite place for this, but so is the coffee shop at the block near where I drop my daughter off at an extracurricular every week for an hour and a half. Along those lines, going out for lunch with just a book for company is one of my favourite indulgences. If nothing else, I try to read between 9pm and 11pm every evening when nothing else is going on. If you tend to spend that time streaming television, maybe consider designating one night a week for reading instead? (I rarely watch TV, which I do think [in addition to my robust iron counts these days] is the most important answer to the question of how I find the time to read.)

4) Make It Easy

Reading doesn’t have to be a chore. It should actually be fun. And while some people’s idea of fun is Middlemarch or War & Peace, accepting the reality that you’re not such people (if you’re not such people) will go a long way toward having your reading habits take hold. Which is to say: read the kind of books that make you relish the turning of pages. Yes, reading widely and challenging yourself is a great way to read, but if you’re striving to read at all, making the experience purely a delight will help a lot. Read short books! Quit books you’re not enjoying. Ignore the books you think you should be reading. Don’t be afraid to trust your tastes and instincts, and to steer your own reading ship.

5) Build a Framework

And along those lines, I like a reading project. I’ve taken on a whole bunch of these this year (more to come in my January essay for paid subscribers), one of which is #WinterofStrout, as I go back and read every book Elizabeth Strout has ever published. I reread all of Madeleine L’Engle’s Austens series back in 2019. In March 2020, which I found it hard to read anything, I found my back to books by rereading Kate Atkinson’s Jackson Brodie books.

If there’s something that interests you, an author you’ve been meaning to get around to, any particular kind of book—books set in a certain place or time period, award-winners from a particular decade, a particular segment of the books already waiting on your to-be-read shelf, anything that might seem fun, and feel good and satisfying—steer your reading ship that-a-way, and let the literary magic happen as those books weave their way into your day-to-day life.

January 10, 2025

Chrystia, by Catherine Tsalikis

It was 2018 and I was riding the subway with my husband and kids toward Bloor/Yonge Station when I started eavesdropping on the family behind us who were discussing the ongoing postal strike, the parents asking smart questions and the kids (who were a little bit older than mine) asking smart questions back, all of them engaging with ideas. Intrigued, I turned around to spy on them, and will admit that the thing I noticed first was that the parents in this very smart family were schlumping about in track pants (ie they were about as well put together as I was). It wasn’t until we’d all disembarked from the train that I realized the mom in question was Chrystia Freeland (my Member of Parliament since 2015; her office sends me a card every Christmas, sometimes two by accident) and by then they’d disappeared up the escalator.

“As her friend,” wrote Katharine Lake Berz a few weeks ago in a Toronto Star about Freeland in the wake of her departure from the federal cabinet, “I have witnessed in her something vanishingly rare in public life: [Chrystia’s] character never wavers, whether she’s addressing world leaders or chatting about her children over coffee.” It was a description that resonated with my own fleeting impression of her in the wild, and which was only underlined by Catherine Tsalikis’s just-released biography.

Chrystia: From Peace River to Parliament Hill, was supposed to come out in February, but House of Anansi Press rushed it into onto shelves just before Christmas following Freeland’s unexpected announcement which led to the Prime Minister’s stament last week of his intentions to resign. And now some are hoping Freeland will step up for Liberal leadership; others crossing their fingers that she gives someone else a chance to go down with the ship before taking on the top job herself. What happens next is anyone’s guess but regardless, Freeland’s story is inspiring and fascinating, and this first book by Tsalikis—an international affairs journalist who became inspired to write this biography in 2020 when she was on parental leave with her first child—does a terrific job rectifying the dearth of stories about Canadian women in public life (as opposed to their quite happily self-mythologizing male counterparts).

Tsalikis traces Freedland’s origins from the stories of her grandparents, on the paternal side, a Scottish war bride who married a farmer from rural Alberta, and maternal, whose lives were defined by European war and turmoil in the first half of the 20th century and immigrated from Soviet Ukraine to Canada in 1948 after their daughter, Freeland’s mother, was born in a displaced persons camp. Freeland was born three weeks premature in 1968, just small enough to be tucked into a desk drawer when her mother—age 20, and finished her first year of law school—returned to work at her father-in-law’s law practice two weeks later. Freeland’s parents would later divorce, but her father’s rural Alberta roots and her mother’s Ukrainian nationalism (and progressive activism) would give their daughter’s character a strong definition. Her brightness shone from a young age, and Freeland would take part in a high school program in Italy, earn her undergraduate degree from Harvard, become labelled as a troublemaker by the KGB during a university exchange in the last days of Soviet Kyiv, and struggle just a little bit to balance the writing of her masters thesis at Oxford (where she was a Rhodes Scholar) with her reporting on the fall of the Soviet Union for the Financial Times.

Chrystia follows Freeland’s story through her years in journalism, her triumphs and professional misses, that unwavering character cited by her friend an absolute through-line, a trait which earns her much admiration and success, but also foes including Vladimir Putin and JAN WONG (who are the true main villains of this story). Tsalikis compiles her story from interviews with friends and former colleagues, and close family members (Freeland’s aunt and sister are key sources), as well as Freeland’s own journalism (she has THOUGHTS about Hillary Clinton as a potential presidential candidate in 2008), and profiles in magazines including Chatelaine and Toronto Life. The result is the portrait of a figure for whom loyalty is a fundamental trait, but who also is unafraid of standing up for what she feels is right, which has included the forces of democracy in the former USSR and as a counter to tyrants all around the world, which puts into context the recent events that didn’t make it into the book, making sense of why Freeland chose to step away from her former boss when she did.

What I loved most about this book, apart from learning the details of Freeland’s extraordinary life and also the finer grains of politics and diplomacy that I may not have understood as well during the years I was watching history unfold via a Twitter timeline, is Chrystia Freeland as an example of somebody who stands up tall before authoritarian forces (which is no small thing when you’re five foot two), how her courage and steadfastness have made her a force to be reckoned with, never to be underestimated. Chrystia Freeland is so far from an ordinary person (however she might ride the subway in such a guise) but there is a lot we can learn from her example about how to respond to our current moment, of how to be clear-eyed and fearless in the face of authoritarianism, and how we might live the values that we know to be true.

January 7, 2025

12 Essential Lessons for Writers from Bookspo Season 2

Bookspo Season 2 was a triumph in all kinds of ways, not least of which was that, in terms of listeners, it grew exponentially over the first season, hitting 4000 downloads by the season finale. Even more importantly, it featured a fantastic group of excellent books published in the second half of 2024 with a terrific range of genres and approaches, with authors celebrating the pleasures and joys of reading and creative inspiration. There is some amazing guidance for writers here, which you can scroll down to get a taste of.

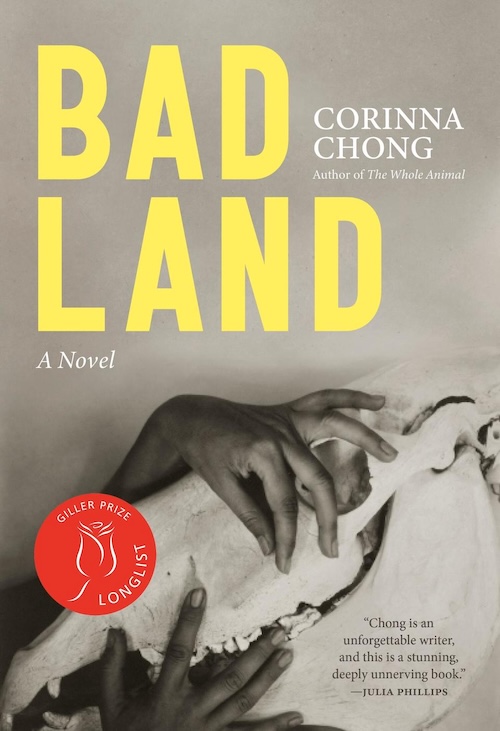

Episode 1: Corinna Chong, Bad Land

The key to a slow-burn plot is building TENSION!

Episode 2: Ayelet Tsabari, Songs for the Brokenhearted

To dare to rewrite old and familiar stories is to be part of a long tradition.

Episode 3: Alice Zorn, Colours in Her Hands

Learn to trust your imagination.

Episode 4: Marissa Stapley, The Lightning Bottles

When you’re basing a character on a real person, it’s only when you let go of their reality in the world that they become truly real in your fiction.

Episode 5: Suzy Krause, I Think We’ve Been Here Before

It’s refreshing to reminded—both in writing and in life—that most people are fundamentally good and trying really hard.

Episode 6: Jennifer Whiteford, Make Me a Mixtape

Give yourself a kind of punk rock permission to create your own vision.

Episode 7: Anne Hawk, The Pages of the Sea

To sit down to write a novel is to be chasing something magical (which can take a long time!)

Episode 8: Kirti Bhadresa, An Astonishment of Stars

Just get started. One can build an entire work of fiction from a list poem! (Who knew??)

Episode 9: Richard Van Camp, Beast

Incredible things can happen when you raise the stakes for your characters.

Episode 10: Priya Ramsingh, The Elevator

A good book makes the reader really care about its characters.

Episode 11: Jenny Haysom, Keep

Fiction allows you to wear many hats and to take on different perspectives.

Episode 12, Andrew Forbes, The Diapause

When you’re writing, it’s useful to keep the books that inspire you close at hand.

January 6, 2025

SPACE

Our Christmas tree was wonderful, lush and redolent until (almost) the very end, and once it was gone, we had so much space it was almost like getting a new room, and so we tidied it. Too many books, as always, so I got rid of a lot of them, and then freed up an entire shelf by relocating my encyclopedia set (circa 1987, Berlin Wall forever) to a space on top of another bookcase that had previously been occupied by crap and clutter. Which means SPACE, my books with room to breathe, my personal library with room to grow. And speaking of SPACE, here is ORBITAL, by Samantha Harvey, which (I will confess!) I was not much looking forward to reading because I’d read her previous novel DEAR THIEF—pitched as a fabulous novel that not enough people were reading, a mark of the state of publishing together—and I didn’t like it at all, perhaps because I don’t actually know the song “Famous Blue Raincoat” on which the novel is cleverly based. So when ORBITAL won the Booker Prize, I didn’t rush out and buy it, but requested it from the library instead, finally sitting down to read it over the holidays, and IT WAS SO GOOD. Yes, it’s me, as ever, with the least hot takes, but I adored this book, which is set on the international space station over the course of a single earth-day, and it really was a love song to our planet and to people and the possibilities when we choose to be our better selves. The image that has stuck on my mind is the floating astronauts at the window watching the earth down below, Harvey giving us the whiteness on the bottom of their very clean socks, which is a perspective I’d never even started to imagine. When I was finished reading, I pushed it onto my teen, who read it in an evening, and then her dad read it too, and we had to buy our own copy because we all loved it so much—and with the relocated encyclopedia there is even room to shelf it now. And I barely know about controversy the book was embroiled in either (it was targeted with bad reviews on Goodreads for supposedly glorifying Russia [um, it definitely does not]) because I’ve spent very little time on social media in the past month, which I’m not sorry about at all, a choice that has freed up mental SPACE for me to read and think and be, and I’m going to carry all that with me into a hopefully spacious new year.

December 5, 2024

The Mighty Red, by Louise Erdrich

I loved THE MIGHTY RED so much, one of those books I managed squeeze in before the calendar year is out, and I’m so glad I did, because it’s easily one of the most wonderful novels I’ve read in 2024. Like the river of its title—which originates in Minnesota and North Dakota, and flows north through Manitoba (where I’ve visited it in Winnipeg!), ultimately to Hudson’s Bay—this novel holds vast amounts of geological time, and history, and sediment, and strangeness, and ghosts, and kindness, and cruelty, and it flows and flows and flows. It begins with Crystal Frechette, who works the nightshift hauling sugarbeets and listening to talk radio, worrying about her daughter, Kismet, and perhaps she should be, because Kismet (who’s just finished high school) has found herself within the sights of Gary Geist, high school jock who’s still not over a recent local terrible tragedy that nobody ever talks about. Even though Kismet is sleeping with nerdy Hugo, Gary proves to be somehow irresistible and the two are married, which feels as wrong to Kismet as it should, but everything has been wrong for her family since her father absconded with the church renovation fund and her mother realized she’s on the verge of losing her house to a very dodgy mortgage. Light, quirky and breezy in places, The Mighty Red is also weighted with substance at the very same time, a story of the land, and the connections to it by Crystal and Kismet, who are Indigenous (Erdrich is a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa), Gary’s mother whose family’s farm was lost a generation ago, farmers who are working on an industrial scale and seeing their soil being ruined by Round-Up, other farmers trying natural methods of controlling pests and organic farming, the whole story feeling a little bit Barbara Kingsolver, and I mean that in the best possible way. This is a story about love, and family, and books and reading, and gardens and weeding, and the 2008 economic crisis, which is also the story of how we got to 2024, and it’s really about everything, like the river at its heart. Awesome and eternal.

December 4, 2024

Taking Stock for December

Getting: set to take a break for the holidays, a break from social media and books published before 1963. It’s my favourite thing and a highlight of every year.

Cooking: Nothing at the moment, and I have NO CLUE what we’re having for dinner, but Smitten Kitchen’s Chicken Soup with Dumplings continues to be a highlight. (The recipe is from Smitten Kitchen Keepers but this recipe is pretty similar.)

Sipping: A Christmas tea from last year that I really need to finish up in case someone gives me some for this year. Full disclosure: I don’t actually like the flavour of most things called Christmas tea.

Reading: The Mighty Red, by Louise Erdrich, omg it’s so fantastic. A last minute addition to my books of the year list.

Thinking: I mean, a little bit? But only a little bit. It’s been a bumpy week in terms of sleeping.

Remembering: When I had babies and all my weeks were bumpy in terms of sleeping

Looking: out the window at a grey and dismal day. There is snow on the ground, but it’s not fun snow.

Listening: to the Fast Politics podcast with Molly Jong-Fast

Wishing: That I wasn’t so tired and that the next door neighbour with whom I share a wall was a little bit quieter in the middle of the night.

Enjoying: This fuzzy ugly cardigan I liberated from my teen’s clothing discard pile.

Appreciating: The blue cheese I ate with apple in my lunch, which was on super discount at the grocery store last week.

Wanting: Dona nobis pacem

Eating: I just had a took the last bit of Smitten Kitchen’s Grapefruit Cake from the baking tin, but the other half of the cake is in the freezer.

Finishing: Everything? (See previous point about getting ready for the holidays…)

Liking: Winter clothes against the winter chill

Loving: Deleting Instagram from my phone every day once I’ve done my posting and not wasting time checking it again after that.

Buying: Christmas presents from small businesses, which the current postal strike has forced me to do, and I’m grateful.

Watching: I finally watched Everything Everywhere All At Once last weekend, and I loved it so much. I am looking forward to watching Season 2 of Bad Sisters over the holidays.

Hoping: Proper snow and winter weather (with lots of tobogganing)

Wearing: Wide legged jeans on a snowy day for the first time in years and am concerned I’ve forgotten what bad idea this is.

Walking: to the swimming pool en route to pick up Iris from school this afternoon.

Following: the news from South Korea

Noticing: How suddenly the trees are all naked.

Saving: money for my kid’s orthodontia!

Feeling: fine, but sleepy.

Hearing: Sounds of sirens in the distance, part of the usual city soundscape.