March 12, 2009

A Brief History of Anxiety (Yours and Mine) by Patricia Pearson

Though I’ve never considered myself laid back (or at least not since I faced a chorus of laughter this one time when I suggested that I was), I’ve never known anything like the anxiety I’ve faced during the last six months since finding out I was pregnant. Numerous times I’ve remarked how fortunate it is that I’ve had no real problems during my pregnancy, seeing as I’ve managed to drive myself absolutely crazy with the imaginary ones. Concocted, I think, because for some reason I’m unable to believe that things are going well without physical evidence of that fact, or any real control over its occurrence. That I’ve never been so powerless has sent me into a semi-permanent state of panic, and so I decided to read Patricia Pearson’s book A Brief History of Anxiety (Yours and Mine)— now out in paperback– in order to make some sense of what I’ve been feeling.

Though I’ve never considered myself laid back (or at least not since I faced a chorus of laughter this one time when I suggested that I was), I’ve never known anything like the anxiety I’ve faced during the last six months since finding out I was pregnant. Numerous times I’ve remarked how fortunate it is that I’ve had no real problems during my pregnancy, seeing as I’ve managed to drive myself absolutely crazy with the imaginary ones. Concocted, I think, because for some reason I’m unable to believe that things are going well without physical evidence of that fact, or any real control over its occurrence. That I’ve never been so powerless has sent me into a semi-permanent state of panic, and so I decided to read Patricia Pearson’s book A Brief History of Anxiety (Yours and Mine)— now out in paperback– in order to make some sense of what I’ve been feeling.

It is sort of ironic, however, that I turn to a book in order to understand anxiety, a book whose thesis is that anxiety is so prominent in our society because rational thought sells us short. Because we’re the kind of people who think our thoughts and emotions can be summed up and explained in a book, just say. But still, Pearson manages this. Her book’s effectiveness partly due to its unique approach– part memoir, part history, all readable and fascinating.

Pearson contextualizes her own experiences with anxiety through a close cultural and historical analysis of the phenomenon. And phenomenon does tend to be the right word– incidences of anxiety are unprecedentedly high in the Western world at this point of time, and Pearson seeks to make sense of this. Suggesting the culprit might be that “implausible myth: that we can assume mastery over our fates.” Which began out of the middle ages with the development of “reason as a new mechanism for keeping anxiety at bay… Reason– or rationalism, more specifically– evolved out of a need to impose order on a world that was both fraught with danger and haunted with ghosts.”

But the ghosts creep in, or rather, the holes in rationalism are all too apparent. Life in its randomness can be absolutely terrifying, particularly for those of us privileged to have become far more accustomed to order and control.

Pearson’s personal experiences colour this history– she writes of her first breakdown, of childhood incidence of fear and anxiety (which occurs, Pearson explains, because of the amygdala (“which act as the sensory headquarters of mammalian fear, [sending] out five-alarm panic signals” to the cerebral cortex, which in a child is “a work in progress, [so] she cannot yet rationally assess the threat…”). She writes of our acknowledgment of anxiety disorders, which weren’t diagnosed years ago, though there have always been people suffering from “nerves” (so-called to in order to make mental problems physical, and eliminate the stigma). Pearson uses her experience as a crime reporter to illuminate our relationship to fear, as well as our attraction to certain versions of it. She also deals with her reliance on anti-depressants, which became an addiction, asserting that these medications are over-prescribed by doctors who are sold by big drugs companies, and have no real understanding of what these medications do.

A Brief History of Anxiety made me feel better. Though hardly a self-help guide, or a typical memoir at all, it was such a pleasure to read, such a relief to see my own experience reflected, and to understand that it takes place in a context outside of myself. What a pleasure also to learn so much in general, a fascinating education. Plus, it’s funny– Pearson is an excellent writer.

March 11, 2009

A cynical deception

“It sometimes seemed to Molly that the library was a place of silent discord and anarchy, its superficial tranquility concealing a babel of assertion and dispute. Fiction is one strident lie– or rather, many competing lies; history is a long narrative of argument and reassessment; travel shouts of self-promotion; biography is just pushing a product. As for autobiography… And all this is just fine. That is the function of books: they offer a point of view, they offer many conflicting points of view, they provoke thought, they provoke irritation and admiration and speculation. They take you out of yourself and put you down somewhere else from whence you never entirely return. If the library were to speak, Molly felt, if it were to speak with a thousand tongues, there would be a deep collective growl coming from the core collection up on the high shelves, where the voices of the nineteenth century would be setting precedents, the bleats and cries of a new opinion, new fashion, new style. The surface repose of a library is a cynical deception.” –Penelope Lively, Consequences

March 11, 2009

The thoroughly unregulated state of Criticism

In what will be my last mention of Canada Reads (for this year), let me say that I’m glad that The Book of Negroes won. Though I don’t think it was a great novel– in fact, it was the most failed of the lot, I think, in those elusive “novelistic terms”– but it is a good book, one I enjoyed reading. I don’t know that it’s the novel all of Canada should read, but it’s one I think most people will like reading, which is certainly something. Though I would definitely be interested in the future to see a panel less composed of books that Canada has read already.

How wonderful though, the sound of readers reading. Ordinary-ish readers talking about books the way that people do, provoking similar conversations that must have continued out in waves. Some of the panelists more astute at literary discussion than others, but the mix was interesting. A spotlight, perhaps, on the kinds of bookish conversations going on all the time in this country amongst people who read. Showing people who might talk books less how to do so, opening up new avenues for readers who might be inclined to just look at books one way (though I think the panel actually could have done a lot more of this. Too many questions were stock.)

I was interested to read a commenter on one blog questioning the use value of this kind of discourse though, wondering why Canada Reads didn’t use “trained critics” instead of celebrities. And the “trained critic” thing really caught my attention, because I don’t think I’ve ever heard it put that way before. How do you become one of those? What is the system of accreditation? As much as free reign of the common reader in the blogosphere is terrifying, what should we make of the thoroughly unregulated state of Criticism?

Though they have editors, of course, but often these people have no formal accreditation either. Often the critics become critics because the editors are their friends, which makes the whole thing about as formal as a blogroll. Academic background might be considered a requirement, but I’m sure there’s a whole league of critics without one who think such a lack is a kind of merit. That you can’t really understand a book until you’ve worked for a while in a logging camp. Maybe no one’s a critic until they’ve read Northrop Frye (which I haven’t done, except for The Educated Imagination, which was quite short). Point being, there is a certain self-appointedness inherent in literary criticism, a lack of a foundation to the trade, and if I were a literary critic, I’d always be terrified of somebody lurking around every corner demanding to see my papers.

Because for all talk of the problems of democratization, I find the fallibility of criticism no less troubling. Common readers on the internet, at least, (should) lay no claim to authority, but critics do, and they are just as often wrong. I’m thinking about William Arthur Deacon’s limited vantage ground, and the writer who has just realized that an older critic was probably right years ago to infuriatingly tell him he was just too young to “get” Anita Brookner. And what about Henry James’ assessment that Middlemarch “sets a limit to the development of the old-fashioned English novel”?

I just know that I was feeling terribly sick last October, and every single book I encountered was tainted as a result, and I hated most of them desperately. Unfairly too, and mightn’t critics have months like that, or at least days? And wouldn’t it be a lot of pressure for one to have to pretend one is convinced one is always right? When, I wonder, does the doubt creep in. Because it should. Critics are only human.

I write all this not to undermine literary criticism, and not as a blogger’s rant about who owns the books really. I actually am an accredited admirer of literary criticism in that I have a Masters degree, in addition to subscriptions to Canadian Notes and Queries AND The London Review of Books, so there. But the idea of the “trained critic” did frame the whole “online literary discourse is in the hands of the masses” hysteria in a brand new way for me, which is one that I think is worth a ponder.

March 8, 2009

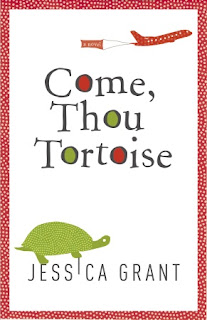

Come, Thou Tortoise by Jessica Grant

Bookwise, “quirky” is a demeaning term, and it only gets you so far. A grander scheme has to be in play in order for a quirky book to mean more than that, and so it is fortunate that in her first novel Come, Thou Tortoise, Jessica Grant so deftly pulls the strings. Fortunate because her premise is so intriguing, and the book itself is so physically appealing, that the substance of the story itself has an awful to live up to.

Bookwise, “quirky” is a demeaning term, and it only gets you so far. A grander scheme has to be in play in order for a quirky book to mean more than that, and so it is fortunate that in her first novel Come, Thou Tortoise, Jessica Grant so deftly pulls the strings. Fortunate because her premise is so intriguing, and the book itself is so physically appealing, that the substance of the story itself has an awful to live up to.

So what is with it with Audrey Flowers exactly? For she’s a strange one, certainly, the product of a rather unconventional upbringing, and in possession a decidedly unconventional point of view. She’s referred to, lovingly, as Oddly, and this is the main thing about her, I think– that she is loved. When she finds out her father is ill and she must fly across the continent from Oregon back to her home of St. John’s Newfoundland, she has friends with whom she can leave her pet tortoise Winnifred, and, however eye-rollingly, they do accommodate the tortoise’s special needs. Upon arriving at home, she’s surrounded by friends and neighbours wanting to take care of her, and when the Christmas light technician finally falls in love with her, in no way are we surprised or unconvinced.

There is much left unexplained in Come Thou, Tortoise, which is its point– upon returning home Audrey realizes there is much she doesn’t know (or has chosen not to know) about her background, and the rest of the story is of her pursuit to fill in the blanks. But Grant takes care not to explain too much to the reader either, not pathologizing Audrey. Though she does have a low IQ, she discovers, when she phones home to tell it to her father, and realizes that “what I had assumed was a high score was not a high score. It just sounded like a high score. It sounded like a not-bad grade, the kind of grade I never got in school.” But she isn’t stupid, she has friends, is utterly charming at times, and adept at the most surprising things– disarming an air marshal mid-flight, for example, and then hiding in the plane’s bathroom with the gun, refusing to believe they weren’t all being hijacked.

The narrative is unconventional, and every so often Audrey’s point of view is interjected by that of Winnifred the tortoise back in Oregon. Who is the voice of reason, as she serves her purpose as a bookmark/papermark in a collection of Shakespearean plays. But there is reason to Oddly Flowers too, an order to her skewed universe which we come to understand as her story progresses. Her narrative enhanced by simple artwork, and also her employment of wordplay, strange spellings, short and abrupt sentences and paragraphs. Grant plays with language in order to show us Audrey’s point of view, to show us Audrey herself, and though the result is quirky as you like, it is also utterly real and convincing.

The grander scheme here at play, however, is not even the fascinating character development at work, but rather something far more fundamental– plot. As the story progresses, mysteries deepen, and it’s a race to the end to see what is what. And what is what, as you might imagine, is not what is expected, nor perfectly clear, but it’s nearly perfect. As is Audrey Flowers herself, and this altogether marvelous and clever book.

March 8, 2009

(Almost) Definitive

Oh, this is good. Melanie from Roughing It In the Books gets a bit more definitive than I did about what she’d recommend for the nation to read. Her choice is Thomas Trofimuk’s Doubting Yourself to the Bone, which I’ve never heard of, and have requested at the library. And I’ve managed to narrow it down to two, which is the best I can do. Pickle Me This’s recommendations for Canadian books the whole nation should read is The Fire Dwellers by Margaret Lawrence, and Russell Smith’s Muriella Pent. The first because I bet you have strong opinions of Lawrence based upon having read The Stone Angel in grade twelve, and this might challenge some of them. The second, because it demonstrates that contemporary Canadian fiction can be fabulous to read, and different than anything else you’ve read before.

March 8, 2009

Small magazine. Big roar.

Over at the Descant blog, I’ve written about the importance of small literary magazines in Canada. This in the wake of federal budget cuts that would eliminate Heritage Canada funding to magazines with a subscription base under 5000. Which, in the words of Bookninja, “is essentially every lit mag out there.” Read my piece, and be sure to join The Coalition to Keep Canadian Heritage Support for Literary and Arts Magazines. At the bottom of the link, find addresses to which you should address your carefully worded letters of protest and support.

Over at the Descant blog, I’ve written about the importance of small literary magazines in Canada. This in the wake of federal budget cuts that would eliminate Heritage Canada funding to magazines with a subscription base under 5000. Which, in the words of Bookninja, “is essentially every lit mag out there.” Read my piece, and be sure to join The Coalition to Keep Canadian Heritage Support for Literary and Arts Magazines. At the bottom of the link, find addresses to which you should address your carefully worded letters of protest and support.

Thanks to Stuart Lawler for the image.

March 6, 2009

Who Does She Think She is?

Because Rachel Power’s book The Divided Heart: Art and Motherhood hasn’t been far from my thoughts since I finished it a few weeks ago, I was very intrigued to discover the new documentary film Who Does She Think She Is? Addressing the same divided heart that Power does, the film is directed by Academy Award winner Pamela T. Boll, and explores the lives of women artists who’ve managed to combine motherhood and artisthood, as well as the question of why they stand out as such anomalies in this experience.

Showing at the Revue Cinema in Toronto tonight, tomorrow and Sunday.

March 6, 2009

What would you bring?

All week I’ve been contemplating the inevitable– whatever will I decide to bring to the table the day CBC calls me up and asks me to be a panelist on Canada Reads? I’ve thought about this even more than I’ve thought about my Academy Awards acceptance speech, which is saying something. In addition to the fact that I’m delusional.

I’m really convinced that there is merit in celebrating underread “classics”, and that new books indeed could do with a boost, but we just don’t know enough about how they’d stand up yet. My longish shortlist would probably include The Fire Dwellers by Margaret Lawrence, The Watch that Ends the Night by Hugh MacLennan, Lady Oracle by Margaret Atwood, and Lucy Maud Montgomery’s The Blue Castle. Of more recent books, perhaps Muriella Pent by Russell Smith, Alligator by Lisa Moore, Nikolski by Nicolas Dickner, The Way the Crow Flies by Anne-Marie MacDonald, or The Republic of Love by Carol Shields.

No doubt you strongly disagree with my picks. But wouldn’t it be boring if you didn’t?

March 6, 2009

I'm glad at least

So maybe now everyone in Canada won’t be reading The Fat Woman Next Door is Pregnant, but I’m glad at least that I got to.