May 25, 2009

What life has been like lately…

Because I am a very lucky lady. And now we’ll just have to wait and see what happens next.

Because I am a very lucky lady. And now we’ll just have to wait and see what happens next.

I’ll be back when I’m ready. I’ll miss you until then.

May 25, 2009

The Children's Book by A.S. Byatt

Fairy tales can be as tricky as the shadowy creatures inhabiting them, and at a Midsummer Party in 1895, the children of Todefright Hall discover just how much in A.S. Byatt’s new novel The Children’s Book. These children are the Wellwoods, progeny of children’s writer Olive Wellwood and her husband Humphrey who is a Fabian banker (neither he nor Olive too uncomfortable with contradictions such as that). The children have just impressed by a terrifying performance of Cinderella by sophisticated puppets, and are intrigued by the differences between the story they’re accustomed to and what they’ve just seen (Cinderella’s stepsisters hacking apart their feet to make the slipper fit, and no fairy godmother or magic pumpkin coach). So it turns out there are many different versions of the stories the children know, and this one is by the Brothers Grimm.

Fairy tales can be as tricky as the shadowy creatures inhabiting them, and at a Midsummer Party in 1895, the children of Todefright Hall discover just how much in A.S. Byatt’s new novel The Children’s Book. These children are the Wellwoods, progeny of children’s writer Olive Wellwood and her husband Humphrey who is a Fabian banker (neither he nor Olive too uncomfortable with contradictions such as that). The children have just impressed by a terrifying performance of Cinderella by sophisticated puppets, and are intrigued by the differences between the story they’re accustomed to and what they’ve just seen (Cinderella’s stepsisters hacking apart their feet to make the slipper fit, and no fairy godmother or magic pumpkin coach). So it turns out there are many different versions of the stories the children know, and this one is by the Brothers Grimm.

The story wasn’t exactly scary, one of the children remarks. Among the grown-ups present in this Bohemian circle is a scholar of fairy tales who agrees, “It should be scary, there was a lot of blood. [But…] these were memories of some other time, long ago, and… they weren’t scary./ ‘They are just like that,’ said Griselda [the child], feeling for what intrigued her, not finding it.” “Like that”, being precisely what they are; not meant to entrance, to sanitize, to edify, to terrify. Folk tales, not children’s tales, which means not geared to any particular audience, and therefore resonating wider.

But these are children who’ve been reared on fairies, whose parents are idealists committed to keeping magic alive in their own lives. Into this circle has also come Philip Warren, a working class boy run away from the potteries, discovered in the basement of the South Kensington Museum (which is to become the Victoria and Albert), and his presence does provide balance and make clear that the Wellwoods’ privilege is rarer than these socially aware children might imagine. But of course Philip is taken with the Wellwoods, and their wild existence, scrambling up trees, riding up and down lanes on bicycles, by the personal stories their mother has written for each of them, by the way that each one of them is his or her own particular sprite.

The difference between the fairy tales the children are accustomed to, the stories their mother writes, and the “like that” stories of the Brothers Grimm is that the latter does not attempt to make itself of another world. Olive Wellwood’s stories are meant to be as “through the looking glass”, but as the story progresses, we see that life itself really is rather “tale-ish”: boys found hidden down hidey-holes, children who appear to be changelings, dubious parentage among the offspring of the Wellwoods and their freewheeling circles, Bluebeardy locked doors with terrible secrets behind them, and vanishings without any explanation.

So that when the children venture out into the world, they find they’ve been sorely deceived. The world is not a firefly-chasing idyll, and the monsters aren’t all fiction– the abuse sustained by Tom Wellwood at public school traumatizes him for the rest of his life, turning him into a Peter Pan type character. The girls grow up to see that for all their scrambling and rambling, society (and their parents) expects something very conventional about the kind of women they’re mean to be. They begin to recognize their parents’ infallibilities, and are taken aback by a world more complex than a good-queen/bad-queen dichotomy. And then comes World War One, into which the boys are led by some kind of Pied Piper, by leaders suffering from “the childish failure to imagine the world as it was” (when “the world as it was” is precisely “like that”).

The Children’s Book is a big book in which time passes quickly, and the reading is gripping. Similarities to Byatt’s best-known work Possession have been made for good reason, though this doesn’t mean the author is simply replaying an old game. She has embarked upon something sprawling here– a story about the invention of childhood, about artistry and artfulness, about motherhood, and the status of women, all with an enormous cast of characters, most of whom are made to be tremendously alive. The novel also stands up as historical fiction, though I don’t like to use that term about books I like and I loved this one– there is nothing dusty, sepia-toned about it. The Children’s Book is decidedly vivid and surprising.

It is true that by the end of the book, Byatt’s immersion of her characters into historical events has perhaps become a bit too complete and the pages sweep by lacking the specificity we’ve seen in the earlier part of the novel. But so too did history seem to in the early twentieth century, and maybe we can understand it this way. Perhaps it’s also the way that time goes when children are grown too, a single day holding far less possibility in and of itself, pages turning faster. Towards the end of the 600+ page novel, but this is the sort one is sad to get to the end of. And here Byatt offers us the possibility of some light, of a happy ending at the end of four years’ bloodshed, and so we can dare to hope too that life and the world could also be like that.

May 22, 2009

Yellow House

Our house is being painted. Anyone who knows our house will also know that this is very good news. That no longer will we live in the shabby blue house, but in the freshly painted yellow one. I think this counts as upward mobility. We are very excited, and glad Baby won’t have to be embarrassed at its premises. We’re also getting a great deal on the painting (ie we’re renters, and so someone else is getting the bill). The only downside is that the last few days I’ve had to endure such disconcerting sights as this one.

Our house is being painted. Anyone who knows our house will also know that this is very good news. That no longer will we live in the shabby blue house, but in the freshly painted yellow one. I think this counts as upward mobility. We are very excited, and glad Baby won’t have to be embarrassed at its premises. We’re also getting a great deal on the painting (ie we’re renters, and so someone else is getting the bill). The only downside is that the last few days I’ve had to endure such disconcerting sights as this one.

May 22, 2009

Books Without Which

Here is a list of books without which I would have had to imagine up my own anxieties throughout my pregnancy. Thankfully, however, these works came with their own inspiration.

- The Monsters of Templeton by Lauren Groff: Willie Upton returns to her hometown “in disgrace”, and what happens in her pregnancy is a plot hinge I’ll not here reveal, but you should read the book to find out why I thought I was crazy.

- Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides: We wanted to find out our child’s gender, but nobody would tell us. So ever since I’ve been convinced that it doesn’t have one. Time will tell.

- Like Mother by Jenny Diski: A baby without a brain! It can happen! It happened to Diski’s Frances, but she was horrid, but then sometimes I am too.

- The Fifth Child by Doris Lessing: The Lovett’s fifth child is a monster who destroys the family, not to mention kicks the crap out of poor Harriet’s womb. The perils of banking too much on domesticity and cozy kitchen tables.

- Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins: The pregnancy goes just fine, and baby Arlo is a dream, but the whole experience brings Ann’s repressed demons back to the surface. I don’t actually have repressed demons, but what if they’re just really repressed?

- Rosemary’s Baby by Ira Levin. Speaking of demons. Because how can you be sure your baby is not the spawn of Satan? And I mean really sure.

- We Need to Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver. Was it nature or was it nurture? Regardless, somewhere along the line Eva went wrong, and brung herself up a high school killer. And it could happen to you (ie me).

- The Baby Project by Sara Ellis. I actually read this book twenty years ago, but skimmed through it recently in a book store because I thought it might be cute. No. SIDS, oh my, and then I started to cry. So the anxiety isn’t going to stop with the birth, it seems. No bumpers on the crib for Baby!

- The Girls by Lori Lansens. I didn’t read this while I was pregnant, so didn’t notice the potential trauma of the birth scene, but then I gave it to a friend who was pregnant, and let’s just say she was plenty relieved to see just one head and four limbs at her first ultrasound.

- Consequences by Penelope Lively. If I read a lot of 19th century literature, surely I’d see even more mothers dying in childbirth. Which is one reason I’m really glad that I don’t read a lot of 19th century literature.

May 22, 2009

Author Interviews@ Pickle Me This: Terry Griggs

It was one of those vivid reading experiences, the first time I read Terry Griggs. Last August, and I was sitting on a bench in a park in Elora Ontario, taking a sunny break in a lovely day’s outing. I was reading Issue 74 of Canadian Notes and Queries, the Salon Des Refuses Issue, and the story was a new one, “The Discovery of Honey”.

It was one of those vivid reading experiences, the first time I read Terry Griggs. Last August, and I was sitting on a bench in a park in Elora Ontario, taking a sunny break in a lovely day’s outing. I was reading Issue 74 of Canadian Notes and Queries, the Salon Des Refuses Issue, and the story was a new one, “The Discovery of Honey”.

First line: “My parents were married in a high wind that was conceived in the tropics and born in a jet stream.” And the whole of the story seemed to be impelled by that wind, by such a tremendous energy.

In reading other stories by Terry Griggs since then, however, I have found that same energy ever-present. Coming from the words themselves, I think, her prose “a language landslide, an avalanche”. She uses language, which sounds obvious, but most writers don’t, not quite like this. Griggs’ new novel is Thought You Were Dead, her own particular take on the crime-fiction genre, and her 1990 Governor General’s Award-nominated collection of stories Quickening has just been reprinted as part of the Biblioasis Renditions Series. I’ve reviewed both books here. Terry Griggs was lovely enough to answer my questions by email from her home in Stratford Ontario.

I: What has been your experience of crime fiction? Prior to Thought You Were Dead, were you an avid reader of it? What writers and books are you most familiar with? What are your thoughts on the genre?

TG: Very little experience, really. Before starting research for Thought You Were Dead, I’d read maybe two or three mysteries. But at some point I became interested in the form and intrigued with its popularity, especially among readers who would not otherwise read genre fiction. I’m an Eng Lit grad, so for the longest time the only kind of work I read was literary. Not a lit-snob, just didn’t know any better, thought that’s where the good stuff was. And it is, of course, but certainly not all. I still think of literature as being in two categories, although for me it’s no longer the literary/ popular fiction divide, but basically what appeals and what doesn’t. Some books fulfill my reading needs and desires and others don’t—it’s as simple as that. I find this a satisfying re-arrangement of priorities and one that opens up the field.

As for books: I discovered Ian Rankin’s Rebus series early on and followed along —to think that his publishers had wanted to dump him at one point before he hit the big time! I’ve read all of P.D. James and Martha Grimes, most of Elizabeth George, and sampled many others.

Kate Atkinson I’ve always liked, and she’s written some mysteries of late (although I believe she doesn’t call them that). Haven’t delved much into the oldie-goldies yet, I confess, although Dan Wells, my publisher has just sent me a copy of Chandler’s The Little Sister.

I: What did you learn about crime fiction while writing this novel? Though you’ve constructed a send-up of the genre, you’re still working within the formula. How was this experience different from your previous writing?

TG: I feel that I’ve always written mysteries, just not the kind that come with the sort of conventions that need to receive at least a nod as one is passing through. And literary does have its own formulas, perhaps less obvious ones. I found the genre to be a fair bit of fun, the form flexible enough to sustain a bit of larky handling. Although this book comes out as a send-up, it’s really just creative play and me inhabiting the genre in my particular, albeit subversive, way, making it my own, leaving my thumb print (evidence!). Plot is perhaps more easily traceable in Thought You Were Dead than in some of my other works, although I’ve never considered it a lesser element. I want to be a good storyteller.

I: I’m always interested in how writers name their characters, and names do seem to be a preoccupation in your work. Most particular, from where did you unearth a name like “Chellis Beith”?

TG: You’re right about the preoccupation. The other night at a reading I was asked about where I’d found the name Chellis, and if I recall, I encountered it in my reading somewhere, possibly in a magazine. I tend to collect names, and sometimes suffer from name-envy if I run across a good one. Someone once told me that they’d named their daughter after a celeb’s kid that they read about in People or Cosmopolitan, I forget which, and I found this proud admission a wee bit sad (okay maybe I am a snob). So in Thought You Were Dead this is how Chel’s mother discovers his name, reading a trashy magazine while waiting in line at the grocery store. Here’s something funny, though: Chellis is an unusual name, but I did run across it again recently in The New Yorker. A woman called Chellis Glendinning has written a book, perhaps it’s an article, entitled “My Name is Chellis and I’m in Recovery from Western Civilization,” which sounds exactly like something my character would write.

Now, his last name is actually borrowed from the town in Scotland where my own ancestral family came from before moving to Glasgow way back when. There’s a quiet little network of Scottish stuff in the book and Beith is one of many.

And, by the way, you have a very interesting name—two Irish counties. Wouldn’t mind hearing the story behind that.

I: The novel is packed with details, detritus from Chellis’ work as a literary researcher. (“The number of bones in the face (fourteen), the name of Sir Isaac Newton’s dog (Diamond)…”) Where did you get all this stuff? Had been saving it? Was it gathered specifically for this project? Do you require this kind of background yourself before you start writing, or can you just sit down with a blank page and go?

TG: Along with the names, I do collect these bits and bobs, often keeping them around for a long time before using them, if I use them at all. I’m not an info junkie, I don’t go scouring, but I find odd bits of information delightful. These sorts of details are telling. A small colourful fact can sharpen focus, or cast an object or subject in a different, more vital light. A sma

ll “fact” even plays a significant part in the book. It’s much easier to find these now with Google, but what you mention I discovered in my own reference books. No, I don’t face the blank page without doing some foraging beforehand, finds which go into a notebook. Usually a couple of notebooks—one for straight research—for Thought You Were Dead, I checked out women inventors and genealogy, among other things—and one for words, ideas, proto-conversations, wordplay, chapter titles, whatever might seem useful.

I: I loved your listing of Chellis and Elaine’s formative reading:. “Mad Magazine, or Archie comics, or PG Wodehouse, and she reading Popular Mechanics, Richie Rich comics, or Virginia Woolf.” Was your formative reading so diverse? What kind of thing did you spend summer afternoons reading out on your porch?

TG: You know, I wasn’t a devoted reader. Or at least reading didn’t occupy a large part of my time, as it does with true bookworms. I did read those comics, piles of them, and the Alice books repeatedly, and Enid Blyton’s adventure series, other stuff long forgotten. Most of the classic children’s books I didn’t read until I was a young adult, and now do read fairly widely, but I have to say I’ve never tackled Popular Mechanics.

I: Chellis notes that “Fiction filtered so surreptitiously into everyday life that you had to keep your eye on it. But not banish it altogether. That would be too too boring. Besides, it was so useful.” Has this been true in your own experience? Whether as a writer or simply a person living an everyday life? And would you, like Chellis’ employer, be annoyed at the terms “fiction” and “falsehood” used interchangeably?

TG: Well, you think of your own family stories, or anecdotes of daily happenings, the rendering of which often enjoy improving tweaks—fiction is a great assist in making life more interesting. It gives a finer, improved shape to conversation. Not that it isn’t true. That trip to the dentist may simply become a funnier, more artfully delivered report—you mine the situation for its subtext, or its less obvious charms. We’re story-telling animals, after all. Falsehood strikes me as being more intentional, purposely deceptive. Fiction transposes life into art, whereas lies are all craft.

I: I’ve thought a lot about how an author is meant to approach her readership, particularly because so many readers demand a pretty immediate kind of satisfaction from a book or a story. But in your foreword to Quickening, you suggest that any satisfaction seemingly withheld might just require the reader to work a bit harder. “If the gist of any particular effort here seems overly elusive, a reader might need to venture in like a beater and drive out the game.” This is a provocative stance to take, to make the reader work as hard as you do. Should reading not be entertainment, a kind of leisure? What are your thoughts on this?

TG: I love the idea of being provocative, but that was actually said as a kind of courtesy. I’ve been given the impression that the stories can be tricky, not immediate, as you say. Can’t see it myself. An attentive reader is all that’s required. So, the statement is just me acknowledging that people bring other reading experiences to a story and perhaps mine may potentially cause a bit of head-scratching. I do think a reading workout is a good thing, forging new neural pathways, etc., but I also believe that entertainment and pleasure are the main reasons for reading. Some of us are just entertained by more tangled offerings.

I: “A language landslide. An avalanche, out the words tumble slam bang, and razzle dazzle.” This from your story “Suddenly”, whose character’s words seem to “put on disguises before sneaking out of [her] mouth.” “Language landslide” or “avalanche” could also qualify as a description of your own prose. But does it really flow so easily from your pen?

TG: Slowly. I write sloooowwwly. Fuss fuss fuss. But this is the interesting thing. The result, or so I’m told, has zip, a certain energy. Words are alive, after all, and possibly I’ve been able to align them in such a way that enables them take off at a real clip.

I: Your story “The Man with the Axe” is much about the creation of fiction. “Two women talking, that’s all it took to spark a birth, a genesis, to entice someone out of the shadows.” Is this your experience? Where else does fiction come from?

TG: From the basement. Martin Amis says that writing comes from the back of the mind “where thoughts are unformulated and anxiety is silent.” The genesis does often seem mysterious, although yes, in my experience it doesn’t take too much to spark something—an image, a word, an expression, even a cliché. (The other day out walking I overheard a woman say to a man, presumably her husband, “I hate to tell you this . . . ” Didn’t catch the rest, but don’t need to—I could happily supply it, probably something he’d really hate to hear.)

I: As a writer for whom language is so important, “finding the exact place the words met events”, it is remarkable that you so often take on the point of view of characters without language— the dogs, the babies, the fetuses. What is the appeal in this for you? Is it the challenge? And how do you find the right words to match such characters’ experiences?

TG: Looking over some of what I’ve written, there appears to be two categories of the speechless. Or near speechless. Those who use language stupidly, cruelly, more as a weapon, and those, you mention, who are invested with emotion and smarts, but can’t express it. I’ve never analysed why I do this, but I assume it’s some presentation of how rich the medium—language—is, how difficult the access at times, or how easily abused. I’ve always been happy to grant sensibility to, well, just about anything. In the kids’ books it’s a fountain pen named Murray Sheaffer. Am a generous dispenser of human goods (and bads). Perhaps I’m a pantheist. People do this sort of thing with their pets all the time, I expect. You interpret a look or a quality and put words in the dog’s mouth to match. The cat says wonderfully astute or affectionate things to you in a cute voice you ascribe to her, whereas what she’s really thinking is how you’d be a tasty little snack if only you were more her size.

I: What are your preoccupations as a writer? Are these different than they used to be?

TG: My main concern is simply to write well, to improve, to keep things lively, and to have a good time doing it. All that has been consistent from the beginning. My fascination with language itself continues, and some subjects keep coming up: the male/female divide, what used to be called the battle of the sexes, and ambiguity—people in situations that they both want and don’t want.

I: Who are your favourite writers? What are your favourite books?

TG: I like the stylists mainly, and poets. So just off the top of my head: Vladimir Nabokov, Eric Ormsby, Hilary Mantel (new book out soon), Beryl Bainbridge, Ted Hughes, Seamus Heaney, Diane Johnson, Julian Barnes, Rose Tremain, Flann O’Brien, Martin Amis, Eva Ibbotson . . . oh lots lots.

I: And finally, what are you reading right now?

TG: I just finished a marvelous book, YA, called The Good Thief by Hannah Tinti. I’m re-reading Little Dorrit. Dickens can wield a sentence most fantastically—away they go. The Letters of Ted Hughes. The letters to his son heartbreaking in retrospect. The whole deal heartbreaking, but the book excellent. I’m going to have a look at A. S. Byatt’s new one, although, like you, her sister is more my cup of tea. Yikes, shouldn’t perhaps mention tea in their company…

May 21, 2009

You must read The Girls Who Saw Everything by Sean Dixon

I like this picture, because my enormousness gets lost in shadow. You also get the blue sky, sunshine, leaves on the trees, that I’ve picked up a little bit of colour (really– this is an improvement), and that I’ve had my nose in a book all day. Or at least for most of the day, when I wasn’t napping, swimming, being visited by a wee delightful baby and her as delightful mother (who came bearing scones), making more strawberry sorbet and eating the first bbq pizza of the season. Obviously, it has been a really wonderful day.

I like this picture, because my enormousness gets lost in shadow. You also get the blue sky, sunshine, leaves on the trees, that I’ve picked up a little bit of colour (really– this is an improvement), and that I’ve had my nose in a book all day. Or at least for most of the day, when I wasn’t napping, swimming, being visited by a wee delightful baby and her as delightful mother (who came bearing scones), making more strawberry sorbet and eating the first bbq pizza of the season. Obviously, it has been a really wonderful day.

But that book I’ve had my nose buried in has really been one of the very best parts of the day. Said book is The Girls Who Saw Everything by Sean Dixon, which I’m not going to review because I read it for fun and it’s two years old, but you can read great reviews at That Shakespearian Rag and Baby Got Books. (Outside of Canada, the book is called The Last Days of the Lacuna Cabal, which I bet is not as well designed as my Coach House edition, though it just might be.) Also check out Sean Dixon’s blog related to the book, and I know you’ll be intrigued.

The whole thing is brilliant. It’s a book that is accessible and complex, hilarious and poignant, serious and light, important and whimsical, and brimming with bookishness for the love of bookishness, and inside jokes and outside jokes, and all the very best things about literature. A completely original story, startling in its specificity, and yet the implications stretch wide. I adored this novel about “a whole bunch of girls and… an intense little book club.” And moreover, if I may say, I love that it was written by a man. Not enough books about a whole bunch of girls are. Reading about The Lacuna Cabal Montreal Young Women’s Book Club was ever-surprising, ever-satisfying. And perfect for a just-as-perfect Thursday.

UPDATE: Largehearted Boy features The Official Lacuna Cabal Playlist: “In the interest of satire, however, Emmy might choose, for Missy, “Common People” by Pulp, adding with a cocked eyebrow that the character played by Sadie Frost in the video reminds her of Donna Tartt’s slutty sister, so there’s a bookish dimension to the choice.”

May 21, 2009

Visit JessicaWesthead.com

I’m pretty excited about Jessica Westhead’s fabulous new website, not just because it showcases her work, but also because of my amazing husband Stuart Lawler’s part in its making (through his great venture Create Me This). And it’s a gorgeous site. Yay, Jessica! Yay, Stu!

I’m pretty excited about Jessica Westhead’s fabulous new website, not just because it showcases her work, but also because of my amazing husband Stuart Lawler’s part in its making (through his great venture Create Me This). And it’s a gorgeous site. Yay, Jessica! Yay, Stu!

May 20, 2009

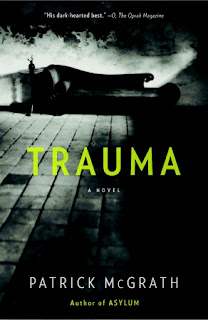

Trauma by Patrick McGrath

Charlie Weir’s mother got a lot of things wrong. Favouring Charlie’s brother Walt and disdaining Charlie’s profession, she once remarked, “Oh, anyone can be a psychiatrist… It takes talent to be an artist.” This statement filed away in the lock-box of Charlie’s mind, which he sorts through all too frequently, seething with ancient resentments. His fixation underlining the fact that many people probably shouldn’t be psychiatrists, him in particular. He lies down on his own couch from time-to-time, and self-regards with much the same insight he accords other people in his life, and eventually it becomes clear that Charlie Weir is a danger to himself and others.

Charlie Weir’s mother got a lot of things wrong. Favouring Charlie’s brother Walt and disdaining Charlie’s profession, she once remarked, “Oh, anyone can be a psychiatrist… It takes talent to be an artist.” This statement filed away in the lock-box of Charlie’s mind, which he sorts through all too frequently, seething with ancient resentments. His fixation underlining the fact that many people probably shouldn’t be psychiatrists, him in particular. He lies down on his own couch from time-to-time, and self-regards with much the same insight he accords other people in his life, and eventually it becomes clear that Charlie Weir is a danger to himself and others.

Charlie, the protagonist in Patrick McGrath’s latest novel Trauma, is at a remove from those around him. This he regards as an intellectual advantage, allowing him a deeper understanding of character, and making him a better psychiatrist in his own estimation. And it is true that for a time he received professional acclaim, working out of an office with a fashionable address, under an esteemed mentor. In the present day, however, circumstances are altered, though Charlie glosses over this (as he glosses over the fact that he grew up a loner, that he’s a man in his forties who has had only two serious relationships in his life.) He can no longer afford a receptionist, his referrals are way down, and one of his few clients has just attempted suicide.

Charlie works with victims of post-traumatic stress disorder, at a time when this is a relatively new field of study. His home in New York City circa 1980 is a fitting backdrop for such an occupation, a sordid, dirty, crime-filled nightmare of a city. His girlfriend Nora, troubled by her own bad dreams, explains them away with the city: “It’s a war-zone, Charlie, you have to be a warrior to live here.” He counsels women who’ve been victims of childhood abuse, of recent sexual assault. He’d previously been working with Vietnam Veterans, but gave this up when he’d started treating his brother-in-law, taken an intervention too far and the brother-in-law had killed himself. Discovering the body, believes Charlie, has been his own trauma, though he’s never had his situation “seen to”. He hasn’t really felt the need to, with his understanding of the pathology of trauma. This understanding, he thinks, is what differentiates him from the men and women he treats who are also unable to control their patterns of compulsive behaviour. It’s what sets him apart.

Of his brother-in-law, Charlie notes that never had he “encountered a man so profoundly alienated from his own humanity that he already felt dead.” Though Charlie himself is so profoundly alienated that he doesn’t even know he’s dead. His absolutely failure of empathy is his failing as a psychiatrist, as a brother, as a husband and a lover. When his brother-in-law dies, Charlie abandons his wife, believing her unable to cope with her husband’s role in her brother’s death. Displaying a complete lack of insight– what she’d be unable to cope with is abandonment in the wake of the loss she’s already been dealt. And now with his new girlfriend, Charlie is unable to regard her character beyond its pathologization, driving her away from him. He’s either being too much of a psychiatrist, or displaying behaviour so dense, it’s hard to believe he’s more than an automaton. He’s accused of being cold, of being clumsy, but fails to take on what these criticisms actually mean.

Charlie Weir is not an absorbing narrator. It’s true that he is cold and clumsy, and it’s a credit to McGrath that his voice doesn’t convince us otherwise– Charlie Weir convinces nobody except himself. (I do wonder about implications of psychiatrist/narrators– their seemingly absolute command of their characters, the characters’ resistance to falling under command. Is psychiatry itself a kind of failed novel?) What Charlie’s voice does mean, however, is that the narrative is not as enthralling as a “psychological thriller” probably should be. There is no “grip” about it, but tension does rise as Charlie becomes increasingly isolated. As we’re left with just his own voice, and the confines of his mind, which is a most terrifying place. His awareness of his breakdown cannot save him in the end, and we’re only forced to bear witness as he ever so clearly and evenly narrates his inevitable descent into an abyss.

May 19, 2009

Voracious

Now reading Trauma by Patrick McGrath, because Emily Perkins mentioned him in her interview last year. I reread Perkins’ Novel About My Wife yesterday, because Tessa McWatt’s puzzler put me in the mood to go back to it, plus Perkins writes about first pregnancy as a really bewildering, terrifying and tender time in a marriage, and I wanted to revisit that. Having the time and space to read voraciously is something I’ve not experienced in a while, and I’m really enjoying it.

And on the internet too– Jessica Westhead has a story up at Joyland.ca, “Todd and Belinda Rivers of 780 Strathcona“. Katia Grubisic in praise of difficult writing at the Descant blog. Seen Reading goes from sea to shining sea (or from Vancouver to Wolfville at least). The wondrous Meli-Mello responds to my post about Mommy blogging. And Marnie Woodrow guest-posting on Sesame Street turning 40 (plus she writes about loving Rita Celli, and who doesn’t love Rita Celli?). From The Walrus, “Water Everywhere, 1982”, which is an excerpt from Lisa Moore’s new novel February (out in June).

And we’re just back from our final midwife’s appointment, which is so strange to consider. And moreover, that in just a week, our Baby will be here. This little person we’ve known so long and haven’t even met yet– I am very excited for that moment to come. (Besides, the reusable baby wipes– I actually sewed them! We’re all ready now.)

May 18, 2009

Long Weekend

Long weekend= Sweet Fantasies Ice Cream, long rainy Saturday with plenty of time for napping, dinner out (with cake and two forks), The Movies (which was Star Trek, because I definitely owed Stuart for a variety of dullish [to him] cultural events he’s accompanied me to), grilled asparagus for lunch, long long walk to Trinity Bellwoods Park and home again (with plenty of bench resting along the way), brunch out, trip to the ROM and the Schadd Biodiversity Gallery, Dufflet treats in the ROM cafe, Greg’s Ice Cream, an afternoon together in the company of our books, three books for me in three days (and another one tomorrow?), squirms from the little one who will be born in just eight days, and yes, this is far too many sweets, I know, but as one is only ever 39 weeks pregnant a few times in a life, we shall shove your dietitian where the sun don’t shine. (Which isn’t here, thankfully. Happy May.)