April 11, 2025

Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre, by Mark Bourrie

Imagine releasing a book about current events in 2025, the challenge of telling a story with everything so unstable and with no indication of how that story is going to end. RIPPER, Mark Bourrie’s new biography of Pierre Poilievre, the leader of the federal Conservative Party, is current right up until the beginning of February, which is less remarkable for a book that I’m reading in April than absolutely incredible. Although the one advantage that Bourrie had was that, while the world is unstable, ever-changing, plotted with twists and surprises, his biographical subject is much easier to pin down. The thesis of RIPPER is that Poilievre is the same person he’s always been, ever since he was Grade 9 student vying for a spot on the executive of Preston Manning’s riding association, attending seminars at the Fraser Institute, and—like many teens—being outraged about the capital gains tax.

Bourrie writes in his introduction: “Is he a bad person? I’m reluctant to make that claim. I think he’s an angry teenager in the body of a grown man. That makes him a stellar opposition politician. It is a bad combination in a prime minister.”

RIPPER is not just about one man, but also about the place he comes from, Alberta, which has always played an out-sized role in Canadian politics compared to other provinces, and Bourrie tells the story of Alberta’s booms and busts, its sense of grievance, and why The Reform Party would emerge from there in the 1990s to remake Canadian politics. Through his story he shows that someone like Poilievre—whose politics and character would have seemed strange and fringe as he came of age—has had mainstream opinion shift in his favour over the last 25 years, through the fall of traditional media, the rise of partisan pseudo-media, a decline in standards of living that suggests there might be something to his claim of Canada being broken (although this decline is a global one), a data-driven approach to courting voters (which lends itself to dirty tricks), and an attack-dog style to politics that’s embodied by Poilievre himself and the people he surrounds himself with.

Bourrie’s narrative voice is personable, engaging and authentic—he makes clear in his introduction that he is not anti-conservative, but that he’s opposed to what Conservatism has become, employing American-style tactics and unafraid of undermining democracy, wholeheartedly embracing the protesters who occupied downtown Ottawa for weeks in February 2022 whose plans were to overthrow the government. Bourrie’s story is fast paced, and gripping, and—with real restraint—not petty (not a word about Poilievre’s remarkable SHE’S ALL THAT-style makeover once he’d become Conservative leader). The book’s depth and focus—as with so many other books I’ve read lately which are most current in their approach—is most clarifying, helping me connect the dots in the chaos of our moment and recent history, making some kind of sense of it. (This is the kind of understanding that inoculates one against becoming a conspiracy theory nut-job).

Imagine releasing a book about current events in 2025, the challenge of telling a story with everything so unstable and with no indication of how that story is going to end. And then, imagine—even worse—not even trying.

Kudos to Mark Bourrie and his publisher Biblioasis for meeting this moment.

And everybody else: read this book. (And also read Catherine Tsalikis’s biography of Chrystia Freeland, who you might remember as the person who orchestrated any and every hope of the Liberal Party doing well in our upcoming federal election.)

April 8, 2025

25 Years of Dar Williams; or I am the One Who Will Remember Everything

In the 1990s, interesting culture circulated via scenes, and zines, underground movements, and pre-internet online communities, and I didn’t know about any of it. Everything I learned about culture in the 1990s I learned from the movie Reality Bites and from pop-culture phenomena my best friend brought home to us from her all-girls summer camp, so I only knew about Lisa Loeb, smoking, the Gap, Ani DiFranco, and flared jeans, and imagined that was enough to built a life upon. Until the internet arrived in 1997 or so, expanding my universe infinitely, though not quite at the start when the internet was still fundamentally unorganized, the only really worthwhile thing I could think of to do there was to log onto random chat rooms and start talking to strangers.

I can’t remember now how I located these chat rooms, how I would have vetted them to discern if they’d be delivering me a salubrious experience, but I was also 19, and not all that discerning. My username was HitMeBaby1MoreTime, so you can probably tell. I actually didn’t get up to this kind of activity all that often, because meeting strangers on the internet was still perceived as fairly embarrassing in mainstream culture, for good reason too, because every time I did so, I’d end up talking about sex, but sometimes life was boring so what else were we to do?

Anyway, I met someone, a philosophy major who lived in the wilds of Iowa and we fell in love, as you do over text when you’re 19 years old and full of angst and longing, and we confessed such longing, and he mailed me a copy of Still Life With Woodpecker, which I thought was oh so romantic, and we exchanged photographs, and I knew that our love was different and extraordinary, though tried to be cool about it in a Tom Robbins fashion, and I kept listening to the Dave Matthews band’s “Lover Lay Down,” and he started emailing me less, and I started making out with my co-workers, and it was 1999, the year with the greatest soundtrack, and soon our undying love died and that was mostly fine.

But I wouldn’t let it go, and the internet enabled me not to do so (the internet is the opposite of closure) and there were search engines by then, so I could keep tabs on the guy, just to see that was he was out there and what he was up to, and he was friends with this woman who had a blog and wrote about music, in addition to writing stories in which he was a character, and it was from her that I first heard of Dar Williams, who had a song called “Iowa,” which brought it all full circle. And by this time, in addition to search engines, we also had Napster, so I could go listen to that song called “Iowa” myself, and unlike anything by Ani DiFranco, whose songs I never liked as much as much I wanted to like them, that song, and all Dar Williams’ music, felt like it had been directly tapped into my soul.

I’ve never been as sad and yearning as I was when I was in my early 20s, so much unrequited love and undelivered feelings, which swirled around my bloodstream in a crazy-making fashion, but Dar Williams felt like a channel for it. She had a sense of humour too, and I appreciated that, that she didn’t take herself too seriously all the time, but that she also knew the tragedy of wanting, and also of February, which could sometimes be so long that it lasted into March, and people who didn’t know how much I adored them.

I didn’t have Napster at home, only at the office where I was a section editor of our college newspaper, so I bought Dar Williams’ CDs (and of course I bought her CDs; I was always buying CDs; a CD was a piece of the world and I could hold it in my hand). Mortal City was my favourite, and I listened to it over and over in my final year at university, 2001/02, a funny year spent in the shadow of a terrorist attack whose ramifications would still be going on by the time I was entering my late 40s (and beyond?), and also on the cusp of the rest of my life. “Once I had everything, I gave it up/ For the shoulder of your driveway and the words I’ve never felt/ And so for you, I came this far across the tracks/ Ten miles above the limit and with no seatbelt, and I’d do it again.”

In 2002, after going through some real things, I took my CDs away with me to England, a huge book of them, taking up most of the space in my backpack, and a few months after I got there, I fell in love with a boy who loved me back and was my match in all the best ways. On Saturdays, we’d wander around the city centre, and flip through CDs together, even though our tastes weren’t identical. Dar Williams released The Beauty of the Rain in 2003, her first new release since I’d become a fan, and once again it felt like we were in sync, with songs like “Farewell to the Old Me,” and “The Mercy of the Fallen,” and songs of love that was actually requited: “I Have Lost My Dreams” and “The One Who Knows.”

I went to see Dar Williams in Sheffield that year, which was about an hour on the train from Nottingham, where I was living at the time. I can’t remember how I’d even heard about the show, or from where I got the wherewithal to plan the journey—I didn’t have the internet at home or work, and would visit the library a couple of times a week to use it—but maybe it was easier to be proactive before I’d come to take for having access to the world in my pocket via a smartphone. I went to that concert all by myself, and I can’t fathom it now—having no phone and navigating a strange city and taking the train home again in the darkness. My boyfriend didn’t come with me, and it’s possible I didn’t even mind that much, because our lives were not so connected then, I’d been independent enough to move across the world on my own, and my love of Dar Williams had always been something of a solitary pursuit anyway. Apart from the blogger who didn’t know I existed who’d been a friend of my internet boyfriend, I didn’t know anyone else who was a fan.

In 2005, my non-internet boyfriend and I got married, and moved back to Toronto, and I enrolled in Grad School, which, much like my early 20s, was more full of hardship and longing than I’d been hoping for, and Dar Williams released her album, My Better Self, which was the last Dar Williams album I’d get deep enough into that I would know every song, and I listened to it when I was sad about school, which it turned out I wasn’t very good at, though I think it was there that I learned the word “hegemony,” which Dar Williams rhymed with “enemy” on a song on the album. I loved her song “Teen for God” and this was a real Bush-era album, really. I loved her cover of “Comfortably Numb.”

In 2009, I went to see Dar Williams at The Mod Club when she was touring her album “Promised Land,” and my husband came with me, now ashamed for having left me to make my own way to Sheffield back in 2003. It was a fun show, and I was pregnant, just a few months away from becoming a mother. She returned to Toronto in 2011, and I had this idea that I’d gone to see her then too, but I can’t find any evidence that this ever happened. She released “In the Time of the Gods” in 2012, and the stories in her songs had drifted far enough that I couldn’t quite catch them anymore, couldn’t hold them and feel them as viscerally as I’d felt the stories she’d written in her own 20s and released on her albums in the 1990s. I did particularly appreciate one line from her song “I Am the One Who Will Remember Everything,” however, as my own life was wrapped up on the wonder and experiences of my own small child “Oh come over here, kid we’ve got all these books to read,/ With the turtles and frogs, cats and dogs who civilize the centuries,/ And in a world that’s angry, cruel and furious,/ There’s this monkey who’s just curious,/ Floating high above a park with bright balloons.”

Last Saturday I went to see Dar Williams again at Hugh’s Room’s new location on Broadview Avenue. And once again, my husband came with me, in atonement for Sheffield more than 20 years ago now, and we had a great time, and were surprised that almost everyone else in the audience was old. I sat beside a woman called Barb who lives in my hometown, directly across from my high school, and it felt a bit like a Dar Williams song, as did reflecting on how I came to love her music like I do. I listened to those songs, and felt like I was listening to my history, especially “As Cool as I Am” and “Iowa,” which we sang along to at her encouragement, and all the people whom I’d ever been came in on the chorus.

April 7, 2025

Steamy: A Menopause Symptomology, by Susan Holbrook

My first child was born in 2009, which was the year that Susan Holbook published her collection JOY IS SO EXHAUSTING, a book bursting with life and bodily fluids. I felt so seen by her epic poem “Nursery,” twelve pages documenting breastfeeding from side to side: “Left: Now that you’ve started solids, applesauce in your eyebrows, I’ve become a course. Right: Spider on the plastic space mobile, walking the perimeter of the yellow crescent moon. Left: Dollop. Right: Now it’s on Saturn’s rings; if it fell off, it would drop right into my mouth. Left: I take 2%, you take hindmilk. Right: Fingers shrimp their way through the afghan holes. Left: I have hindmilk.”

And now that I am 46, constantly itchy and getting my period every nineteen days, signalling the beginning of my perimenopausal journey, Holbrook has delivered STEAMY: A MENOPAUSE SYMTOMOLOGY, a poetic memoir that’s hilarious and searing at once. The baby from “Nursery” is all grown up now (see Symptom 29, “Dry Eyes,” in which the grown child is dropped off at university, and the poet does not cry. “For most of my life you could count on me to descend into blubbery convulsions at a filmic dog death or an airport farewell or, of course, a real dog death. I would readily cry for sad or happy reasons any old time. Now you can rarely squeeze a sob out of me. Maybe I’ve used up all my tears along with my eggs.”) and the poet is contending with other changes (see Symptom 3, “Cessation of Menses”: “I’m not sure why I never went to the doctor./ Maybe because I was so relieved each time my tsunami ended that I didn’t want to think about it again until three weeks later when I ruined the *other* side of the couch cushion”).

Like the symptoms of menopause themselves, Holbrook’s symptoms can go off on a tangent and sometimes end up being about raccoons or the time she broke her arm at age 11, which I don’t mind in the slightest because, like menopause, this book is full of twists and surprises, and, unlike menopause, it’s also very funny and rich with meaning (see Symptom 33, “Reduced Libido” for former, which is mostly about her grandpa, and Symptom 30, “Panic Disorder,” for the latter, “A year later my heart dances with the daffodils. I found a drug that muffles my panic but not my joy.”).

April 3, 2025

How to Survive a Bear Attack, by Claire Cameron

I never read Claire Cameron’s 2014 novel The Bear. My kids were 5 and 1 when the book came out, and at the time (and even now) I felt far too tender to contend with a story in which parents are killed in a bear attack and their small children are left to fend for themselves in the wilderness. Not unrelated to the arrival of my children OR my aversion to reading the story was also an anxiety that had settled into my consciousness like a fug and years later would knock me totally flat. (It’s curious to read my first novel and see it there, when my protagonist takes in the big old trees in her neighbourhood, and how vulnerable she is to dangerous objects falling from the sky, how vulnerable even her home is, and that safety is an act of faith more than it’s ever a fact). But that same anxiety, which I’m learning to live with and understand better, was absolutely why I very much wanted to read Cameron’s latest book, the memoir How to Survive a Bear Attack. Because it’s a book about anxiety and fear, and living with them both, and the fact that maybe we’ll even be strong enough when we have to step up to fight, but we can’t plan these things, and the danger is never quite where we imagine it will be.

Cameron’s father died of skin cancer when she was nine-years-old, and in the years after, she found her way back to herself, and through the weight of her grief, by immersion in the great outdoors. She became an avid canoeist, wilderness trekker, rock climber, tree planter, finding solace in nature and wildness, and also power in her own strength and abilities to succeed at the challenges the wilderness threw up at her, including run-ins with bears. She even fancied that she’d know what to do if the unlikely event of a bear attack occurred. Such attacks were rare, but Cameron she was interested in stories of these outliers, like the Canadian couple killed in Algonquin Park in 1991. Understanding what happened to them became an insurance of sorts, because if she could just figure out what they’d done wrong and do it differently, then she would be fine. It was also gateway to her literary breakout, with her second novel’s great success.

But when the danger finally arrived, it came from a place that Cameron had never seen coming. At 45, she was diagnosed with skin cancer, and learned she had a rare genetic mutation making her especially susceptible. She was advised by her doctor that her optimal UV exposure was precisely none. Facing her own mortality brought her back to her memories of her father, a professor of Old English, and the stories he’d taught and shared with her of monsters and dragon slaying. She calls on his courage and strength to help get her through her diagnosis, and many surgeries, and also begins to consider anew the story of the couple killed in Algonquin Park all those years ago. What had she missed from the story the first time? What other lessons might there be? How was she to find her home in nature again when parts of her life she’d always taken for granted—paddling in the sunshine on a lake that reflects the light like a mirror, for instance—had suddenly become perilous. And what of the bear itself? Where, exactly, was the heart of this story?

I tore through this memoir in a day, absorbed by every thread in this multifaceted narrative. The bear stuff BLEW MY MIND and Cameron’s own journey is gorgeously and emotionally wrought, and I came away with just the kind of perspective I’d been hoping to get. “Being alive is one big risk and it will end in death, but the bridge between those two things is love.”

April 3, 2025

New Book News!

This is my big news! It even made Publisher’s Lunch! I’m really really happy and looking forward to sharing this book with you.

April 2, 2025

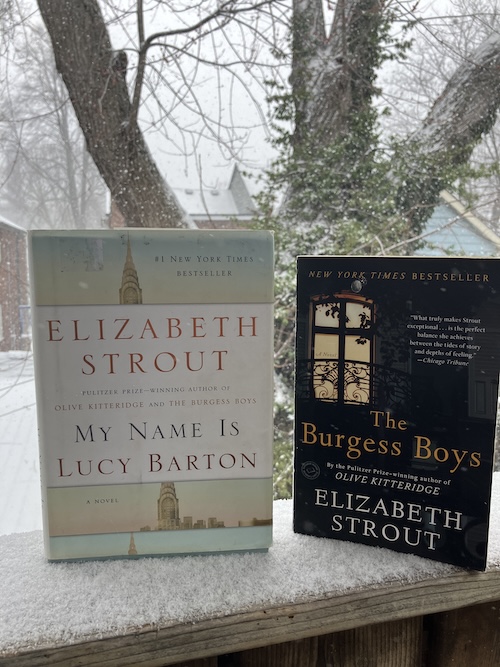

#WinterofStrout Update

I was going to talk about how my #WinterofStrout had gone on so long that it was finally spring, but now there’s a blizzard outside, so I guess I don’t have to. (There are now ice pellets blowing against my window.) After Olive Kitteridge, The Burgess Boys was my next Strout reread, which I first read almost exactly two years ago and adored. And having read Tell Me Everything since then, I love it even more now, and it seems less an outlier among Strout’s novels structurally speaking now that I’ve also read Amy and Isabelle and Abide With Me. It’s definitely a companion novel to Tell Me Everything, just without Lucy and Olive, but with the brothers, and a court case, the setting of Shirley Falls, and a consideration of class. And then I reread My Name is Lucy Barton, for the fourth time (I think?), but my first time since seeing the stage play in November, which made the book mean even more to be and made sense of Lucy’s mother’s character in a way I’d never been able to do from reading her on the page. It’s funny how this novel is so short and spare (which is how I’ve been able to reread it so many times) but I still found passages and points I hadn’t paid attention to when I’d been through it before. And now next up is Anything Is Possible, which I’m so excited to read again because it plots the points in Strout’s universe in a way I’d been hoping Olive Kitteridge to do but it didn’t. It will be wonderful to encounter so many characters in this book that I’m relatively familiar with by now.

April 1, 2025

At a Loss for Words, by Carol Off

“Populist politicians blame the government for the disparity between classes, feeding public resentment, distrust and anger. But that anger isn’t aimed at the 1 percent who play little to no tax, or at those whose obscene wealth can now pay for private trips into space for just lark. Instead of resenting the greed that drives the income gap, people direct their anger exactly where the agents of chaos want it directed—at government and civil society.”

Instead of looking for sense and meaning in newspaper live-blogs lately, I’ve been digging deeper and reading books, which definitely has helped with overwhelm, even when the books themselves are far from feel-good. (I’ve made a list of such books at 49thShelf: “Instead of Refreshing Your Feed.”) And former CBC journalist Carol Off’s At a Loss For Words: Conversations in an Age of Rage was positively chilling, instead of feel-good, but it was also so wise and made all sorts of connections between disparate things that look like random chaos from a distance, but Off shows that there’s nothing random about it. And that for decades, right-wing billionaires with nefarious intentions have been putting the pieces into place to lock in power for authoritarian leadership. And part of the way they’ve done this is by undermining our language, which is also our common ground, turning meaning inside out so that it becomes hard to know if anything is true. Off selects six words she explores to show how this has happened: Freedom, Democracy, Truth, Woke, Choice, and Taxes. Where do these words and ideas come from? How have their meanings and solidity been undermined, and who benefits from this happening?

What makes At a Loss for Words so important is its Canadian lens, highlighting the connections between what happens in Canada and the US, but also the ways in which Canada’s history is different. Throughout the book, she returns to her own childhood growing up, the child of parents who had rose to the middle class, and for whom the lessons of Europe in the first half of of the 20th century were close enough that they did not take for granted living in a pluralistic society where neighbours could think differently but also still have fundamental values in common.

This book was published in a world where the outcome of the 2024 US Presidential Election was still unknown, and it’s prescience is startling and disturbing—especially the part in the chapter in “Woke” in which she outlines Viktor Orban’s systematic dismantling of the university system in Hungary, how he brought these institutions under government control in a manner that the current US administration seems to be emulating to the letter. The implications are real and scary—former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper is now head of a global organization dedicated to electing right-wing governments around the world, and Orban has called him “a great ally.”

At the end of the book, Off tells us that it’s still not too late to change course, which seems harder to believe here in 2025 than it might have a year ago. But knowledge and understanding of what’s really unfolding is imperative, regardless and, having read this book, at the very least I feel better equipped to meet the considerable challenges of the moment.

March 31, 2025

A Bird in the House, by Margaret Laurence

My Manawaka journey continues! Except that I picked up A Bird in the House thinking it was the book Laurence published after A Jest of God, but it was not! Not that it matters entirely, because the books themselves aren’t published in chronological order—The Fire Dwellers takes place before A Jest of God, but was published after it. (I would be curious to know what order these books were written in, and one way to get to the bottom of that would be to reread Laurence’s wonderful collection of letters to publisher Jack McClelland.) A Bird in the House is also a story collection and so it was likely written across a wide span of time (with stories first published in magazines like Ladies Home Journal, Chatelaine, Atlantic Monthly, and by the CBC, which makes me nostalgic for such a literary landscape). Anyway, I’d already started reading when I figured out my mistake, and because I’m cool and laidback, I just kept on going, and am not bothered by the mix-up at all. (Note: This is a lie. I am! Alas.)

Okay, so A Bird in the House might be the Manawaka book with which I’ve had the longest and least complicated history. The copy I have, I think, might have been swiped from my mom’s bookshelf, a Seal paperback, which had become entirely unglued and fell apart when I opened it after all these years. So I went to BMV and found a newer secondhand copy, a New Canadian Library edition with a foreword by Isabel Huggan, who I was friends with before the pandemic but we’ve fallen out of touch. And just like a story from Huggan’s collection The Elizabeth Stories, I believe I first encountered one of the stories from this book (either “The Sound of the Singing” or the title story “A Bird in the House”) in The New Oxford Book of Canadian Short Stories in my Grade 12 English class (which I wrote about here). I must have read the entire collection (which also constitutes a novel, a bildungsroman) at least once, but I don’t think I read it more than once, and the aspects of the story I remember are those I encountered in the short fiction anthology—young Vanessa, and the brick house where her grandfather lived, and the harbinger of death that was the sparrow, and then her father died not long after.

Unlike, say, The Stone Angel, stories from A Bird in the House are well suited for young readers, and Laurence’s narration is more traditional in these stories than her other books are, which are very much interior-focused. Vanessa MacLeod, on the other hand, is looking outward, telling the stories of her parents and grandparents, of the world around her, albeit not connecting any of the dots to understand or explain what those stories mean, and this means that my impression of these stories was that they were simple and straightforward, but it turns out that was just by perspective that was simple and straightforward, and I’m now wise enough to understand what was going on between the lines in these stories, the pains and struggles of these characters’ lives. I really read it and thought was about a house, a girl, and a bird, but there is so much more than that. My own dawning awareness is analogous to that of Vanessa herself:

“For me, the Depression and drought were external and abstract, malevolent gods whose names I secretly learned although they were concealed from me, and whose evil I sensed only superstitiously, knowing they threatened us but not how or why. What I really saw only was what went on in our family.”

And when she gets a little older and writes about the music of her youth: “The music seemed the only music that ever was or ever would be. I had no means of knowing that it was being set into the mosaic of myself and that it would pass away quickly and yet remain always mine.”

About war: “It was then that war took on its meaning for me, a meaning that would never change. It meant only that people without choice in the matter were broken and spilled, and nothing could ever take the place of them.”

March 27, 2025

Storm the Ballot Box: An Inside’s Guide to a Voting Revolution, by Jo-Ann Roberts

The big picture continues to be overwhelming and terrible, and I’m finding solace at the granular level, with books like STORM THE BALLOT BOX, by Jo-Ann Roberts, a long-time journalist whose career in politics began when she was a federal candidate for the Green Party in 2015. After years of covering Canadian politics, Roberts figured she had a good sense of how her candidacy would unfold, which turned out not to be the case, partly because politics is always different when you’re in the thick of it, but also because 2015 was a pivotal point in politics, with new dynamics brought on by social media, less local news coverage, a promise by the Liberals of voter reform, and a whole lot of weirdness. (Remember the guy who peed in a mug?).

In this breezy and engaging book, combining memoir and reportage, Roberts shares her experiences in politics, and also shares her frustration with the fact that so many Canadians she encountered through her door knocking were disengaged with the political process. (Not me! I’ve only missed one election in my adult life, when I didn’t bother to show up to vote between David Miller and Jane Pitfield for Mayor in 2006, because I knew he was going to win and was fine with that, and I’ve been embarrassed about this ever since, that I would have been so blase about this right who other people have died for.) She also shares her understanding, however, about why it might be so easy for so many to feel disengaged with the political process—the allure of strategic voting, which limits real choice; the way that polls end up determining the story instead of telling it; the broken promise of proportional representation; parties engaging in disinformation instead of talking about the real issues that matter to Canadians; the unequal ways in which Canadian political parties are funded; and more.

To all these problems, Robert offers real and practical solutions—and also smart explanations, though I must admit that I still don’t understand what a polling margin error means in the slightest, but that’s the point, really, and maybe I should stop reading up on polling numbers like I do. What if media outlets were only permitted to release polls within a particular margin of error? What if Elections Canada was made responsible for voter turn-out? Roberts proposes a referendum on electoral reform, followed by an election under the new rules, and then another referendum for Canadians to determine if they wanted to keep the process? What if political parties were removed from ballots? (And did you know that political parties were not recognized under law in Canada until 1970?)

Storm the Ballot Box is as fascinating as it is inspiring. This is the kind of revolution we need.

March 26, 2025

A Return to Analogue

I remember the friction of pulling that tag off the shelf, its plastic a perfect fit inside my palm, and how it felt like I was holding a key to something vital. I would carry the tag to the counter where it would be traded in, more often than not, for the 1988 Lily Tomlin/Bette Midler vehicle Big Business on VHS, a video my sister and I rented from our local corner store so many times that when I watched it again more than 30 years later, I knew the whole thing by heart.

Video rental was such a big deal for the first 20-some years of my life, its high stakes made clear by the FBI warnings that preceded every film, the responsibility to be-kind-please-rewind, and the sinister curtains behind which the dirty movies were kept, not to mention how a certain title’s availability or otherwise would have the power to make or break one’s sleepover party.

I could chart the course of my life by video stores, from the pre-chain hometown joints, to Bay Street Video (which lives on!) during my university years, to our local video store in Japan where we’d pray for subtitles, and then the Queen Video locations we frequented back in Toronto until the last one closed in 2019—although it wasn’t very frequent by then because we didn’t have a DVD player any longer.

But at the end of January, we bought another one, part of a grander plan to combat the overwhelm (at which we’ve not always been successful, I’ve got to say; sheesh, it’s been a time) by cutting ties to corporate entities where possible and focusing on tangible finite things. Streaming services never once delivered the satisfaction I’d received from bringing my plastic tag up to the counter, and they also made my children wrangey and frustrated as there was never anything they wanted to watch enough but always something to suggest they should not give up trying.

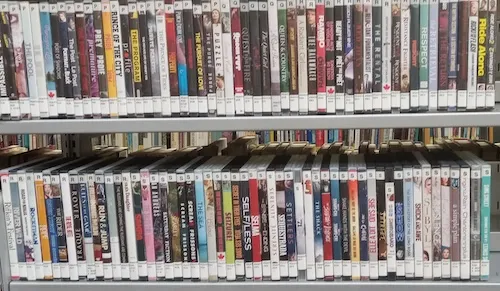

So we went back to DVDS, and I want to tell you about the joy of heading to the library DVDs shelf with my 11-year-old daughter for the very first time, about what it felt like to recall the sweet serendipity of this kind of selection and to have her experience it for herself. At dinner the night before, her dad and I had been remembering the 1986 movie Flight of the Navigator, and there it was on the shelf. She also borrowed a collection of Pixar shorts and Inside Out 2, and we felt so lucky and excited at finding these—for free, even. We’re currently #850 of 1125 on the library holds list for the DVD copy of the Wicked movie. We’ve got time and are happy to wait.

Our local secondhand/overstock bookstore has an entire basement full of tapes, CDs, records, VHS, and DVDS, and more, and I’d never been there before a couple of weeks ago when I went to scratch my new DVD itch, and descending those stairs was like arriving back in time (it didn’t help that the walls are the same shade of orange as the High Fidelity poster). We got Four Weddings and a Funeral because my Paddington-watching children have never known floppy-haired Hugh Grant, and Midsomer Murders, and the first season of Glee. There were no Velcro tags in the place, but I could almost imagine them, especially when I closed my eyes and listened to the sounds of flipping media all around me as customers were shuffling and riffling, almost paradise (and yes, I picked up a copy of Footloose while I was there).

-Check out “I don’t want to live in a world without video stores” from the West End Phoenix

(This post is taken from my monthly ENTHUSIASMS newsletter, which is free to all readers. You can sign up for it here. Or you don’t have to, because this site continues to be my home on the internet and you can always find me here!)