October 24, 2010

My Secret Summer Reading Project (which is no longer a secret)

It’s all out in the open now, what I spent my summer reading (in addition to everything I’ve already told you about). This summer my own rereading project was waylaid because at the beginning of June, I began my duties as one of three jurors for the Quebec Writer’s Federation First Book Prize. I had twenty-five books to get through, a stack that did seem quite daunting, but also exciting to consider– some of the books were so incredibly beautiful, others looked fun, and others fascinating.

And their diversity is the first thing I want to talk about– what it was like to evaluate novels, short story collections, memoirs, current-event nonfiction, history books and poetry against one another. Every book had been written with its own singular intention, and it was my place to deem how successfully these intentions had been realized. It had me considering the works far more broadly than I would have otherwise. And what joy it was to read so many of these, breaking me out of my own stiff reading habits. A pleasure indeed (and an honour too).

What was even more a pleasure, however, was to spend my summer visiting Montreal. Which, of course, I only did through the books I encountered, but it was enough. Amazing. I’ve actually spent very little time in Montreal myself, and have always known it best through books (like I do most places), but these books had me so steeped this summer in the city’s culture, history, and geography that I feel I know it almost well now. And from where I sit, it’s one of the most vibrant, beautiful cities in the world, and I do look forward to visiting again.

Anyway, I had a marvelous time. Too bad you weren’t there! And congratulations to the stellar shortlist.

October 21, 2010

We read The Dalhousie Review

In The Dalhousie Review Summer 2010 issue, editor Anthony Stewart writes that the magazine has started a return to its roots: the print issue design has been streamlined to fit with the magazine’s online presence (though I have to admit the blah minimalism seemed lacking to me, but alas); digital archives will soon be available back to 1921 when the magazine was born (fabulous); and though they continue to publish high quality prose and poetry, there has been a shift in their non-fiction from academic to more general-interest, which had been the intention of the magazine’s first editor 90 years ago.

In The Dalhousie Review Summer 2010 issue, editor Anthony Stewart writes that the magazine has started a return to its roots: the print issue design has been streamlined to fit with the magazine’s online presence (though I have to admit the blah minimalism seemed lacking to me, but alas); digital archives will soon be available back to 1921 when the magazine was born (fabulous); and though they continue to publish high quality prose and poetry, there has been a shift in their non-fiction from academic to more general-interest, which had been the intention of the magazine’s first editor 90 years ago.

Though they’re still mid-shift, I suppose. Jason Holt’s “Partworks” begins with promise– a list of great works of art, “all deservedly famous, all provocatively unfinished.” He then attempts to find a place for these works within aesthetic theory, but I confess that I didn’t understand anything in the entire piece. I think I became officially lost at, “If trying to preserve an intuitive view of partworks as occupying a middle-ground between non-artworks of the quotidian kind and bona fide artworks has such drastic theoretical consequences*…, then this might be taken as a reductio of the intuitive view.” (*I love the idea of “drastic theoretical consequences” though– what might they be? Getting your Adorno in a knot?)

Philip Beidler’s “History and Memory in the Great War Paintings of John Singer Sargent”, on the other hand, is accessible, fascinating, and accompanied by colour prints(!) of three of the paintings. Beidler takes into account the different nature of Sargent’s commissions, who they came from (British vs. American), and when in his career they came in order to understand the diversity of his WW1 portrayals. This is exactly the kind of stuff the Dalhousie Review should be after– devourable to those of us who didn’t know John Singer Sargent from a sewing machine, but after we’ve read it, we do.

Many of the stories in this issue take on “History and Memory”, as Beidler does. Julia Zarankin’s “The Fabric of Nostalgia” ruminates on language, letter writing, and how we assemble ourselves and others from words written on a page. (Full disclosure: Julia is my friend. I thought she was brilliant before she became my friend, however, so my bias means less than one might think.) Lynda Archer’s “A Heart in Saskatoon” takes what could be saccharine premise (a woman going to meet a man who long ago received her dead brother’s heart), and enlivens it with a dose of suspense and an interesting treatment of heart imagery. Andrea Bennett’s “The Falls” is also a reflection on the past, and though the story lacks depth where we’d like more, Bennett skirts cliche in all the right places and her ending is absolutely perfect. Alexis Lachaine’s “Gas” is situated in the present, but a present that is decidedly fixed and sepia-toned, backward looking (though less so than it supposes– something is going to happen, but this is not the point), and featuring some of the strongest writing of the bunch. Patrick Hick’s “Buster” was a small town hockey story that reminded me of Finnie Walsh.

Two other stories in the magazine were “Napoleon’s Eyes” by Vanessa Farnsworth, and “Dress Up” by Drew McDowell, both unconventional domestic comedy/tragedies. In the former, a wife watches her husband desperately try to insurance payout, putting their lives and home at risk in the process. McDowell’s story is about a husband who follows his wife too far into drugs and risque sexuality, and features two truly stunningly powerful moments, but lacks a satisfying ending.

(The poetry didn’t do it for me. I must say that I didn’t work very hard to make it do it for me, so the fault is probably my own rather than the poetry’s)

This is the first of what I hope will be a series of postings on literary magazines, as I venture outside of my comfortable subscription list for a single issue of something that’s new. I’m pleased to picked this one up, and to glimpse a magazine in transition, in the hands of an editor whose vision and passion underlies the entire issue.

October 20, 2010

Bunting!

Clipper Tea marketers, you’ve done it again! I was compelled to buy your tea solely on the basis of its gorgeous packaging, and then you went and made this television advert complete with bunting. Bunting! It even falls down, like the bunting in my kitchen, because masking tape can only ever be so sticky. And I am raising this point now because I want to post a photo of the bunting in my kitchen, which was an idea I stole from my friend Bronwyn, but we both thought it was a good one because India Knight has bunting in her kitchen too. I made my bunting out of origami paper, and it has made the kitchen one of my favourite rooms in our house (rivalled only by the living room, the hallway, Harriet’s room, and my attic loft). Other fantastic objects in this photo include my breadbox, the Blackpool tea towel, a wind chime made out of buckets and watering cans, and the first two of a row of five photos of a British supermarket cereal aisle. In unrelated news, my horrid craft blog has been updated. Click here to answer the question that’s been obsessing everyone: what has Kerry been knitting lately?

Clipper Tea marketers, you’ve done it again! I was compelled to buy your tea solely on the basis of its gorgeous packaging, and then you went and made this television advert complete with bunting. Bunting! It even falls down, like the bunting in my kitchen, because masking tape can only ever be so sticky. And I am raising this point now because I want to post a photo of the bunting in my kitchen, which was an idea I stole from my friend Bronwyn, but we both thought it was a good one because India Knight has bunting in her kitchen too. I made my bunting out of origami paper, and it has made the kitchen one of my favourite rooms in our house (rivalled only by the living room, the hallway, Harriet’s room, and my attic loft). Other fantastic objects in this photo include my breadbox, the Blackpool tea towel, a wind chime made out of buckets and watering cans, and the first two of a row of five photos of a British supermarket cereal aisle. In unrelated news, my horrid craft blog has been updated. Click here to answer the question that’s been obsessing everyone: what has Kerry been knitting lately?

October 20, 2010

Harriet has a meta moment

Okay, I’ll admit to not being exactly capitivated by the plots, but 17 month old Harriet is absolutely obsessed with the Hello Baby Board Book series by Jorge Uzon. These books have only lived in our house for a very short period, but Harriet keeps taking them off the shelf and demanding they be read to her. When she isn’t demanding they be read to her, she is struggling to walk around the house holding all four books at the very same time. Clearly, Uzon has found an audience for his beautiful photography.

Okay, I’ll admit to not being exactly capitivated by the plots, but 17 month old Harriet is absolutely obsessed with the Hello Baby Board Book series by Jorge Uzon. These books have only lived in our house for a very short period, but Harriet keeps taking them off the shelf and demanding they be read to her. When she isn’t demanding they be read to her, she is struggling to walk around the house holding all four books at the very same time. Clearly, Uzon has found an audience for his beautiful photography.

Our favourite part of all the books, however, is in Go Baby, Go! when the baby discovers another baby within the pages of his book. And the amazing thing about this is that he has discovered the Night Cars* baby! We love Night Cars, and pointing to the baby (who, when he finally falls asleep, has an adorable tendency to stick his bum into the air) is Harriet’s favourite part of the book (except for the fire truck). So to see the baby in her book pointing to the baby in her book, and then to point to that baby herself– I think Harriet is discovering that the bounds between fiction and reality are ever-blurry. Or maybe I’m just projecting.

*Do you know Night Cars? The absolutely gorgeous urban bedtime book by Teddy Jam, who was aka the late novelist Matt Cohen? I bought this book for Harriet when I was four months pregnant, and signed the inside cover “from Mommy and Daddy”, which was kind of amazing then. And still is. Its rhymes punctuate our days– “Garbage man, garbage man, careful near that dream. It could gobble up your garbage truck, and then where would you be?” Also notable for being a book about *Daddy*. And donuts.

Anyway, I didn’t know this book either until I heard Esta Spalding reading it as part of Seen Reading’s Readers Reading almost two years ago. And I am very glad I did.

October 19, 2010

Two books I bought today

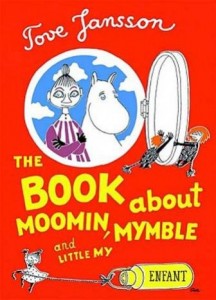

Harriet is receiving The Book About Moomin, Mymble and Little My for Christmas this year, after a recommendation from Charlotte. The book is published in English by the Drawn & Quarterly children’s imprint Enfant, and is really, truly a work of art. It is our introduction to Moominism, and if this book is any indication, I think I’m in love. The drawings are vivid, whimsical, and easy to get lost in, and the characters crawl through the story through a different hole in every page. I am also obsessed with the typography, and the translation from Swedish which still seems to rhyme absolutely perfectly. I look forward to reading this one to pieces.

Harriet is receiving The Book About Moomin, Mymble and Little My for Christmas this year, after a recommendation from Charlotte. The book is published in English by the Drawn & Quarterly children’s imprint Enfant, and is really, truly a work of art. It is our introduction to Moominism, and if this book is any indication, I think I’m in love. The drawings are vivid, whimsical, and easy to get lost in, and the characters crawl through the story through a different hole in every page. I am also obsessed with the typography, and the translation from Swedish which still seems to rhyme absolutely perfectly. I look forward to reading this one to pieces.

Also, tonight I made the world’s shortest appearance  at Amy Lavender Harris‘ book launch in order to congratulate her and pick up a long-awaited copy of Imagining Toronto. An expansive and almost exhaustive study of how Toronto has been rendered in its literature, how this city we know so well has been imagined by its writers. Harris writes, “Toronto is a city of stories that accumulate in fragments between the aggressive thrust of its downtown towers and the primordial dream of the city’s ravines. In these fragments are found narratives of unfinished journeys and incomplete arrivals, chronicles of all the violence, poverty, ambition and hope that give shape to this city and the lives laid down in it.”

at Amy Lavender Harris‘ book launch in order to congratulate her and pick up a long-awaited copy of Imagining Toronto. An expansive and almost exhaustive study of how Toronto has been rendered in its literature, how this city we know so well has been imagined by its writers. Harris writes, “Toronto is a city of stories that accumulate in fragments between the aggressive thrust of its downtown towers and the primordial dream of the city’s ravines. In these fragments are found narratives of unfinished journeys and incomplete arrivals, chronicles of all the violence, poverty, ambition and hope that give shape to this city and the lives laid down in it.”

October 19, 2010

Notables: Street Haunting by Virginia Woolf

May/June 2005 was certainly an exciting time in the history of the universe– Penguin Books had just turned 70, and I was about to get married. These two occasions colliding one day on Oxford Street in London where I happened to be shopping for a wedding dress, and had stopped into a Waterstones where Priscilla Presley was scheduled to be appearing. Though I was devastated to discover that we’d shown up for Priscilla precisely one day late, so I never got to see her promoting her new book. Instead, I bought a copy of Virginia Woolf’s Street Haunting, a gorgeous little volume (for 1 pound fifty!) that had been published as part of Penguin’s birthday celebration.

May/June 2005 was certainly an exciting time in the history of the universe– Penguin Books had just turned 70, and I was about to get married. These two occasions colliding one day on Oxford Street in London where I happened to be shopping for a wedding dress, and had stopped into a Waterstones where Priscilla Presley was scheduled to be appearing. Though I was devastated to discover that we’d shown up for Priscilla precisely one day late, so I never got to see her promoting her new book. Instead, I bought a copy of Virginia Woolf’s Street Haunting, a gorgeous little volume (for 1 pound fifty!) that had been published as part of Penguin’s birthday celebration.

So it’s not an especially rare book, or an old one, but it’s notable to me. It contains six examples of Woolf’s essays and short fiction, which blur the lines between the two particularly. And to be honest, I would have had an impossible time ever cracking this book and getting through its 56 page had I a month later not happened to sign up for a course in Woolf’s essays and short fiction at UofT where I was to begin graduate studies in September. Woolf’s essays and short fiction meaning nothing to me previously– I’d bought the book because I liked the idea of Woolf more than I really understood her work, and I’d signed up for the course because it was the only Woolf-course available.

My performance in the course was positively dismal, and if you never see me in graduate school again (which, I assure you, you won’t!), the challenges I faced in that course are all the reasons why. If by challenges, of course, you mean the brick wall I kept banging my head against in an attempt to understand academic theory, which, oddly enough, no one had ever mentioned to me during my undergraduate career, or just my efforts to get along in grad school life in general, which met with very poor results. Grad school taught me that I’m really not cut out for grad school, BUT, I learned so very much along the way. Like how to read Virginia Woolf, and that changed everything.

Because I found that her essays and short fiction really are the key to understanding her larger projects, and the foundations behind them. From reading her book reviews, and her Common Reader essays, and her short stories, I found myself positively immersed in her work, and my general academic stupidity aside, I became fluent in Woolf. I understand Woolfian arguments now, and how they turn and wobble, and the straight path was never her intention, so if you get confused reading Virginia Woolf, it’s because you’re supposed to.

And I couldn’t have learned any of this all on my own– if I’d taken a break from wedding planning during that day to read Street Haunting as I was swept along with the Oxford Street tide, I would have found myself baffled and disappointed. I would have read all that weirdness and thought the problem was me. I was sorely in need of a little guidance to illuminate just what was going on, and never mind that that guidance was just showing me the door out of academia, but en route, oh what I learned as I shuffled to the exit.

I learned to read Virginia Woolf— because there’s a knack to it, of course. It’s hard and weird, but infinitely rewarding, and the universe is a more mesmerizing place for it. I could pick up a copy of Street Haunting now and follow its meanderings for hours.

So I like this book because it’s a souvenir, and also because I learned to read Virginia Woolf is another way of saying I have lived.

October 18, 2010

The Journey Prize Stories 22

In the Canadian literary circles I tune into, everybody bitches about everything. It’s sort of a standard rule. Which makes it notable, I think, that I’ve never heard anybody complain about the dearth of a thriving literary magazine culture in this country. That I’ve never heard a writer tell me that they’d had it with Canadian lit. mags, and now they’re sending everything to some address in New York City or London. That L.A. is where the bucks are. Though no one ever says that here is where the bucks are either, but the bucks are not the point. Though they should be. Why aren’t they? And probably we could all start bitching about that.

In the Canadian literary circles I tune into, everybody bitches about everything. It’s sort of a standard rule. Which makes it notable, I think, that I’ve never heard anybody complain about the dearth of a thriving literary magazine culture in this country. That I’ve never heard a writer tell me that they’d had it with Canadian lit. mags, and now they’re sending everything to some address in New York City or London. That L.A. is where the bucks are. Though no one ever says that here is where the bucks are either, but the bucks are not the point. Though they should be. Why aren’t they? And probably we could all start bitching about that.

We take these magazines for granted, however. These little outfits all over the country, often driven by volunteers, undersubscribed but over submitted to. Whose funding was cut by the Federal Government a while back, remember? These magazines that have provided stellar platforms from which our best writers have launched their careers. Magazines that readers like me have fallen in love with, and thrill to see in my mail box about four times a year.

Of course, I go on about small magazines all the time. I also spend a lot of time celebrating the short story, and the fantastic work being created in the genre by new Canadians writers. And I realize that this all can be a bit overwhelming– what magazine to read? What writers? What stories? How to get a feel for any of this? So I am very happy to answer all these questions with The Journey Prize Stories 22.

Each year, Canadian literary magazines submit their best short fiction for The Journey Prize, which was founded in 1988 when writer James Michener donated the Canadian royalties of his novel Journey. This year’s judges were Pasha Malla, Joan Thomas and Alissa York, and they culled the list down to 12 stories which appear here. The collection was a pleasure to read, an exciting sampling of the diverse forces at work in Canadian short fiction, and an example of the amazing talent being spotted and fostered by our smaller magazines.

The three stories selected for the shortlist were all deserving– Krista Foss’ “The Longitude of Okay” is a gripping story of a school shooting incident and its aftermath, fiercely plotted, and sparsely drawn with perfect detail. Devon Code’s “Uncle Oscar” is told from the perspective of a young boy who is privy to disorder all around him, and orders that disorder in his own way. That young boy’s perspective never falters. And finally, Lynne Katsukake’s “Mating” takes place in Japan, where a husband is reluctantly supporting his wife in a an effort to find a wife for their son, and the narrative is a subtle meditation on family, love and parenthood.

For me, other standouts in the bunch were Laura Boudreau’s “The Dead Dad Game”, which is also a young person’s perspective on a broken world, and that world is realized with such humour, poignancy and quirky charm. Ben Lof’s “When In the Field With Her at His Back” is a disorienting story with all of itself encapsulated within its very first sentence, and yet it manages to be surprising. I loved Andrew McDonald’s “Eat Fist”, in which a young Ukrainian-Canadian math prodigy’s language lessons from a female weight lifter blossoms into her very first love affair. Eliza Robertson’s “Ship’s Log” is the story of a young boy who’s digging a hole to China, perhaps to escape from a home where everything has gone awry, and the gaps in this playful narrative are particularly devastating to great effect. Mike Spry’s “Five Pounds Short With Apologies to Nelsen Algren” begins, “No one ever tells you not to fuck the monkey…” and goes from there, and never falls over its feet with its furious pace.

As I read this collection, I tried to think of a way to link the stories, to find a way to talk about them all together in a review, but they each read so differently, and I never figured out how. But now I see that the small magazine thing was the underlining factor all along anyway– incredible stuff is happening here. And if you want to add your support to a really thriving culture, The Journey Prize Stories is a good place to start.

October 15, 2010

Vote vote vote for The Girls Who Saw Everything

Remember when I was 40 weeks pregnant and obsessed with Sean Dixon’s The Girls Who Saw Everything? I sure do, and even with everything that’s happened since, I’m still pretty obsessed with it. And Stuart also enjoyed it, and he’s quite a different kind of reader than I am, so that says something about this book’s appeal. Anyway, when asked to champion a Canadian book from the last ten years as a candidate for CBC Canada Reads 2011, The Girls… came to my mind immediately. Because, as I told the good people at the CBC:

it’s challenging, literary, fun, plot-driven, ripe with allusions, a good read even if you don’t get the allusions, a book about girls that’s written by a man, because it’s a celebration of bookishness, and because it’s about the most bizarre book club you could ever imagine.

October 15, 2010

There is no other way

“Nevertheless, Friedan raised a critical point: “The only way for a woman, as for a man, to find herself, to know herself as a person, is by creative work of her own. There is no other way.” What Friedan understood, but what many of us ultimately forgot, is that simply landing a job does not guarantee self-actualization. At the same time, the homemaker who simply learns to cook dinner, keep a garden and patch blue jeans will probably not find deep fulfillment either. Those who do not seriously challenge themselves with a genuine life plan, with the intent of taking a constructive role in society, will share the same dangers as the housewives who suffered under the mystique of feminine fulfillment; they face what Friedan called a “nonexistent future”.”– Radical Homemakers: Reclaiming Domesticity from a Consumer Culture by Shannon Hayes