November 30, 2010

2011 Canada Reads Indies Picks!

When I was deciding to do Canada Reads Independently again, it was mostly because of the Fantasy Panel I had in mind. Imagine a group of smart people, of book experts, each with diverse and formidable talent that collectively is more than a little awe-inspiring. What incredible books might such readers recommend? And then my Fantasy Panel came true– they all said yes. And came at this project with so much thoughtfulness and enthusiasm that I’m overwhelmed, truly honoured, and really excited to tackle a fantastic stack of books. Read below and I have no doubt that you’ll be excited too.

When I was deciding to do Canada Reads Independently again, it was mostly because of the Fantasy Panel I had in mind. Imagine a group of smart people, of book experts, each with diverse and formidable talent that collectively is more than a little awe-inspiring. What incredible books might such readers recommend? And then my Fantasy Panel came true– they all said yes. And came at this project with so much thoughtfulness and enthusiasm that I’m overwhelmed, truly honoured, and really excited to tackle a fantastic stack of books. Read below and I have no doubt that you’ll be excited too.

Toes in my Nose ( Doubleday 1987) was written for my children when I was in my twenties, published when I was 30 and I’m still doing nonsense and learning how to be writer. I’m thrilled my children’s books like Mable Murple (re-release 2010 Nimbus) are now available for Harriet and a second generation of readers, including my own grandchildren, but I’m ever eager to explore other genres and voices. Kiss the Joy As It Flies, first adult novel, (Vagrant 2008) , was shortlisted for the Leacock Award, found and keeps finding a solid readership. Lately, I explored a male point of view and teenage angst in Pluto’s Ghost (Doubleday, fall 2010). I’ve been working on another collection of adult poetry since Gooselane published In This House Are Many Women in 1992, but confession: I’ ve been hoarding a collection of short stories on and off for twenty odd years. I’m a storyteller at heart and the “story” is still my favourite genre to read , quite possibly because it hearkens back to that oral tradition I came to love so early on. Before I’m 59, I’m hoping I”ll have a collection I’ll try to publish. For education, honorary doctorates and all that awards stuff people put in obituaries (but were hard won and deeply appreciated), folks can go to www.shereefitch.com.

The Book: Play the Monster Blind by Lynn Coady

I expect a lot from stories. I want them to knock me upside the head, crack my heart open and turn me inside out. I want a collection to make me laugh and cry and unravel me. To provoke. To haunt. To linger ever after in the inner circle of stories I keep tucked in the core of my being. I want stories with characters I’ve never met or characters I don’t necessarily like, but ones I can grow to understand, if not to love. Likewise, I like meeting characters I think I know until I scratch and sniff below the page and have to look again. Stories can be loud or quiet, they can be juicy or subtle, limn high brow, middle brow or low brow worlds, explore domestic drama or whiz me to exotic locales. Whether they are set in the past or in present, I also want them to be timeless.

Ultimately, however, I crave stories that leave me reeling– or maybe real-ing is a better. I want to have that aha feeling that, however briefly, makes me think I’ve seen deeper into the heart of things because the storyteller told a tale from that yearning place in the centre of themselves. They’ve dug into the minepit (mindpit?) from which a vibrant truth of theirs blasts forth and an authentic voice shines. Soul changing, shape shifting fiction. I want the book to vibrate in my hands. I want to feel the undistorted spirit of the writer present, while they are absent. Oh, yes, the creation should appear effortless not overwrought. No tell-tale scrubbing of the eraser.

Okay, so I would never have said it like that in grad school but my pick does almost all of the above.

Play the Monster Blind was published in 2000, ( Doubleday Canada) when Lynn Coady was thirty years old. (Proof again, like this year’s Giller winner, that chronological age does not discriminate when it comes to gifts of vision and a wisdom beyond years).

Coady’s prose has that edgy energy, a borderline cockiness I admire, and she’s wickedly funny. Her humour ranges from the wry to ribald, and her voice is versatile: upsetting and exhilarating. Forget gender-typical nice girls and cozy quilt-like feel good stories, strings of pearls, head nods to decorum or wombs of our own. Reader won’t find themselves cushioned by history, or strolling an art gallery or enjoying symphonies or even nestled in middle class suburban families with the kids at basketball games. Meet a world of big dog rage and oversized underpants, boozing, boxing, irreverence, complicated sex, cheap hotel rooms and searching men and women. Coady’s east coast of Canada , especially industrialized Cape Breton, is a landscape populated by the never get ways, the come from aways and the go aways. In Coady’s world there are razor -edged, truth-saying tellers; the smart and sassy, the off kilter and quirky and ordinary. From Paula Moron ( ball a more ‘n more ) to Nurse Ramona in the Devil’s Bo-Peep, to Jesus Christ, Murdeena, they are an unforgettable lot.

Beneath Coady’s laser eyed scrutiny and sure hand, we read of folks groping in the dark, trying and often failing to connect with each other and fully inhabit their lives. They are souls partially blind to their all too often own monstrous natures as they stumble about like Boris Karloff in the move Frankenstein. Coady’s narrative stance seems at times like a shrug of amused wonder but there is a steady pulse of fierce compassion, the kind that comes from an awakened mind and a beating heart, present in every story.

As a reader, and writer, and yes, an east coast woman with a different background and range of experiences, the real triumph of this collection is the fearlessness and delicious joy which lifts these stories into a hard won kind of grace. Laughter as medicine. A ride not just a read. I think Canada needs to read Play The Monster Blind, so we can see parts of ourselves and/or each other as clearly and wisely as Coady does.

Nathalie Foy would almost always rather be reading. She lives in Toronto with her husband and three sons and piles of books that multiply at an alarming rate. Thankfully books have no expiration date. Nathalie is an occasional instructor of Canadian Literature at the University of Toronto, and after being given Anne Fadiman’s Ex Libris: Confessions of a Common Reader by a student, she began collecting books about books and blogs about them at Books About Books.

The Book: Truth and Bright Water by Thomas King

Thomas King’s Truth and Bright Water is a delight. Each time I read it, I am newly charmed. It is brimful of offerings: part mystery and part coming of age, the story is peppered with red herrings and liberally seasoned with magic realism and social critique. There is tension throughout, and tragedy, but both are leavened by King’s inimitable comedic style. King has dialogue–and the non-sequitur in particular–down to a fine art, and one of the great joys of reading the book is how the characters come alive in their snappy exchanges.

Truth and Bright Water, an American town and a Canadian reservation, sit across from each other on the border between Canada and the U.S. The story takes place during Indian Days, as Bright Water prepares for the yearly deluge of tourists. There is also the homecoming of two former residents of Bright Water: the “famous Indian artist” Monroe Swimmer, whose art is one of the novel’s crowning glories, and the narrator’s black sheep of an aunt. Borders, revenants, the carnival atmosphere, family conflicts, ghosts and magic all make for exciting and dangerous territory, and we follow the teenaged protagonists, Tecumseh and his cousin Lum, as they negotiate it.

The narrator is Tecumseh, who often does not understand the significance of what he is telling us, and the deft handling of the ironic gap is another of the book’s delights. Thomas King’s novels are richly allusive, and it helps the reader to know, as Tecumseh does not, that the character Rebecca Neugin is real, a survivor of the Cherokee Trail of Tears, that there is more to a story than just the words, that things are not always what they appear.

In 2004, King’s Green Grass, Running Water was one of the final two books for the CBC’s Canada Reads, and one reason it got bumped was that several panelists called it a book for literature majors. To an extent, I agree. It is a book best read with the assistance of discussion, whether for a class, book group or CBC panel. Truth and Bright Water is a far more accessible novel, but it still makes us work and think. To my way of thinking, the very best books do.

Chad Pelley is a multi-award-winning writer from St. John’s. His debut novel, Away from Everywhere, was a Coles bestseller, won the NLAC’s CBC Emerging Artist of the Year award, and was shortlisted for the for 2010 ReLit award and the Canadian Authors Association Emerging Writer of the Year award. His short fiction has won awards, been anthologized, and accepted for publication by leading literary journals such as Prairie Fire. Chad facilitates a creative writing course at Memorial University, sits on the board of directors at the Writers’ Alliance of Newfoundland & Labrador, runs Salty Ink.com, and has written for a variety of publications, such as The Telegram and Atlantic Books Today.

The Book: Still Life With June by Darren Greer

Still Life with June won the 2004 ReLit Award, was a NOW Magazine top ten book of the year, and a finalist for the Pearson Canada Readers’ Choice Book Award. It’s also been optioned for film. I knew all that before I read it. What I didn’t know, but knew by page 9 or 10, was that this is one of the most innovative, original, memorable, and cleverly constructed novels I’d ever read.

It’s all there in Still Life with June: refined writing and a distinctive style paired with an engaging story. It also succeeds in pairing heavy subject matter with levity. Greer masks the sadder aspects of this story with a comedic tone, so that the dark side of the story feels all the more potent when he chooses to haul off that mask of humour. This is very effective. This novel is outright funny and downright grave: not something most writers could pull of so flawlessly.

In Cameron Dodds’ take on the world there are two kinds of people: “losers who know they are losers, and losers who don’t know they are losers.” Cameron, a small-time writer, considers himself a loser who knows he is a loser. He works at a Sally Ann drug and alcohol treatment centre, where he steals the file of Darryl Green, a recent suicide case, and gets so engrossed in the file that he translates Darryl’s life into fiction, going as far as befriending the deceased’s sister: a Down Syndrome patient named June, who he regularly visits.

It’s a book about a lot of things: the bonds and tensions unique to blood relations, a truthful and amusing exposé on the life of emerging writers, or even the ways cats have it knocked. But more than anything, it’s a novel about identity, replete with well-crafted and complicated characters, i.e very human characters. Every single character is in denial about who they are, and without giving too much away about the brilliant, page-turner of an ending, Cameron quite literally gets lost looking for himself.

Most novels leave a reader with a memorable story, or character, or ending. Maybe you’re even struck by a distinctive new style or narrative structure, or the thematic meat of a book. Greer leaves you with struck by all of that. I would recommend this book over 95% of Canadian novels published this decade, and it’s one I’d adapt if I was a screenwriter. As a novelist myself, this novel made me fondly jealous I didn’t write it, and remains one of only 3 novels I’ve read a second time. The style, structure, and story complement each other to perfection; there is nothing I would change about this book.

Carrie Snyder is the author of Hair Hat (Penguin Canada, 2004), a collection of stories chosen for last year’s Canada Reads Independently. Her second book, a collection of linked semi-autobiographical stories, is scheduled to be published in 2012, by House of Anansi. She blogs as Obscure CanLit Mama.

The Book: Home Truths by Mavis Gallant

It is with some trepidation that I put forward Mavis Gallant’s collection of selected Canadian stories, Home Truths, published nearly two decades ago, and which carries a faint whiff of the old-fashioned.But I simply must. Though Mavis Gallant is a master of the short story form, with a brilliant mind that shines on the page, I am willing to bet that her books will never be chosen for CBC’s parallel competition. I am also willing to bet that many readers and fans of Canadian literature, who would be moved and delighted by her work, are unfamiliar with it.

Skip the essay that opens the collection, and make your way directly to the stories. (Read it when you’ve gotten to the end, and are familiar with her work. In it, Mavis Gallant defends herself as a Canadian writer; she has lived as an expatriate in Paris, France for most of her writing life, and one has the sense of a writer who feels snubbed by her country; I hope we are less parochial readers two decades on).

The stories themselves … brilliant, precise, particular, detailed, mysterious, elegant. Each is set in a place and a time rendered in immaculate detail: Montreal in the 1920s and 1940s, Northern Ontario after the second world war, Geneva of the 1950s, Paris, 1952. As with any collection, some stories will grab a reader more than others, but all have something to offer: think of it as a smorgasbord for the mind.

So many of the characters in these stories are alone, or nearly alone: children abandoned by parents, as in “Orphans’ Progress”; unprotected children who find a cobbled-together comfort: “Jorinda and Jorindel”; an immigrant mother and her child riding a train into a landscape that might as well be the moon: “Up North.” And so many of the stories are heartbreaking. They peel away the masks of sophistication, and evoke the primitive emotions we begin hiding from ourselves at a very young age. Yet one has hope for the characters, who have hope for themselves, and are possessed of reserves no one would guess of them: resourcefulness, determination, spirit.

What sets Home Truths apart, and the reason I chose it from among Mavis Gallant’s many marvelous collections, is its final section: linked semi-autobiographical stories about a young woman, Linnet Muir, who returns to the city of her birth, Montreal, and makes her life up with daring and courage. The character, though still a teenager in the first story, “In Youth is Pleasure,” is completely alone in the world; and yet she is not afraid. Her invention of herself, in “Between Zero and One,” is bold, but she does not consider it so: “I was deeply happy. It was one of the periods of inexplicable grace when every day is a new parcel one unwraps, layer on layer of tissue paper covering bits of crystal, scraps of words in a foreign language, pure white stones.” The Linnet Muir stories do not progress in linear fashion, yet they hold together effortlessly, in the accretion of images that create a lost world, and a remarkable character.

As a writer, I read Mavis Gallant often; more often than anyone else. She is who I turn to when I want to remember how stories work. My editing brain turns off and I surrender to a mind that is quicker and wittier than my own. Her writing is complex, layered, intelligent; yet I read her for pleasure, easily, and with the delight of eternal discovery.

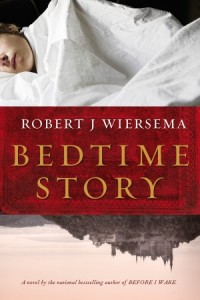

The Champion: Robert J. Wiersema

The Champion: Robert J. Wiersema

Robert J. Wiersema is a writer, reviewer and bookseller. His first novel, Before I Wake, was a national bestseller and a Globe and Mail Best Book in 2006, and has been published in more than a dozen countries. His novella, The World More Full of Weeping, was shortlisted for the Prix Aurora in 2010. His latest novel, Bedtime Story, was published in November. He lives in Victoria with his wife Cori Dusmann, and their son Xander.

The Book: Be Good by Stacey May Fowles

Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love is one of my favourite short story collections. It features some of Carver’s finest work, including “Why Don’t You Dance” and “Tell The Women We’re Going”, and every story is parsed and clean and brutal, exploding in their final lines with savage emotional force and resonance.

It’s that collection – including its title, which when repeated aloud takes on the quality of a mantra — that comes to mind when I think about Stacey May Fowles’ debut novel Be Good.

The 2007 novel from the Toronto writer and essayist orients around the question of what it means to “be good” for a loose constellation of twenty-somethings, with close focus on friends Hannah and Morgan. The novel doesn’t so much unfold as it does explode in a narrative-impressionist flurry, jumping from Montreal to Vancouver, from character to character, across time and meaning. The initial sense of flurry, however, only momentarily obscures a tightly organized, thematic- and character-driven work which builds through pain and doubt and fragile joy and sexual violence to moments of catharsis and heartbreak.

Fowles’ prose is reminiscent of Carver’s, almost clinical in its precision, not cold but incisive. Its starkness, and her frequently brutal insights, underscore a novel that is relentless in its pursuit of hard emotional truths. What does it mean to “be good”? What does it mean to be a friend? Where does one find meaning in a world seemingly devoid of significance? And what of love? In a way, Be Good revolves around love, about its levels, its possibility, its risk, and its impossibility. Fowles’ words are surgical, cutting through the defenses, laying bare the heart. Be Good is what we talk about when we talk about love, and about the brutal silence when the words just don’t come.

In one of the pre-pub blurbs, Michael Redhill wrote “Be Good announces the arrival of a wonderful new voice in Canadian fiction.” I couldn’t agree more.

November 29, 2010

The Sentimentalists by Johanna Skibsrud

The 2010 Gillers picked a book out of the blue for me, pushed me to pay it closer attention than I might have otherwise, and the payoff was enormous. This is literary awards at their very, very best (and also makes clear that “what sells” is self-fulfilling prophecy, marketing types take note). I was lucky enough to get my mitts on a Gaspereau Press edition of Johanna Skibsrud’s The Sentimentalists, which meant that my book was a book of a book, hand stitched, thick paper, a dust jacket for a paperback. Such care; for me this is “what sells” and I bought it.

The 2010 Gillers picked a book out of the blue for me, pushed me to pay it closer attention than I might have otherwise, and the payoff was enormous. This is literary awards at their very, very best (and also makes clear that “what sells” is self-fulfilling prophecy, marketing types take note). I was lucky enough to get my mitts on a Gaspereau Press edition of Johanna Skibsrud’s The Sentimentalists, which meant that my book was a book of a book, hand stitched, thick paper, a dust jacket for a paperback. Such care; for me this is “what sells” and I bought it.

I pushed through the story in a way I might not have had the book not been so celebrated. There was a lack of precision in the language, a distance between the reader and the story, and I kept putting the book down and not rushing to pick it up again. But I think this was as the book was intended to be read, a long slow journey without a destination in mind. Because when we arrive at the end of the book, at our destinations, the answers are still not all apparent. By which I mean that if you’re reading to find out what happens next, you’re probably going to find this book disappointing.

An intimacy creeps into the story though, between these people and I, as two fighting sisters drive their ailing father across the country. Sisters are at each others’ throats, banding together only to rally against their father who keeps lighting up cigarettes and forgetting to open the window– the family dynamics are set in motion, and they tell us who these people are and where they’ve come from; we are there. That the sisters have constructed their lives out of pieces, and now they’re older, they’re both discovering that lives are pieces after all. When the narrator discovers her partner with another woman, she goes to be with her father where he’s living with Henry, a family friend. It was at Henry’s where she and her sister spent their childhood summers, on the banks of a lake that had flooded where a town used to be, and being there is to have an awareness of the drowned town, ever-present whether it can be seen or not.

Which serves as a metaphor for the story of her father, who is called Napoleon Haskell, and his relationship to Henry, whose son Owen served with Napoleon in Vietnam. During the summer the narrator spends with her father and Henry, she constructs the story of her father’s past, what happened to Owen, and what had happened to Napoleon to fracture the rest of his life into just pieces of pieces.

Throughout the story, Napoleon is hard at work on crossword puzzles, and these puzzles are an indication as to the novel’s construction. Blanks are filled in from clues, with their correctness not always assured, but the puzzle takes on its own shape anyway. The puzzles pieces include Skibsrud’s prose, sentences with their many, many clauses, as well as allusions to poetry and film, and concludes with a transcript from Napoleon’s testimony of what he witnessed during his time as a soldier. The transcript provides many of the answers the rest of the story had been withholding, and creates an altogether satisfying conclusion to the novel, which doesn’t provide all the answers, but the effect is very much of a whole.

The Sentimentalists is sentimental, unabashedly so, but perhaps if you don’t like sentimental, find a book with another title. Because I liked this book, which portrays the humanness of men at war, particularly during this time when we’re all being brainwashed to believe that “soldier” and “hero” are synonyms. I like what it says about history and story– that the former can never been captured, and the latter has wings of its own. I like the tender gruffness of its men, that love and poetry are what remains, that some things may be irreparable but that doesn’t mean they’re truly broken.

November 28, 2010

Recent Reviews

A couple of my reviews of books I’ve enjoyed are now online at Quill & Quire: see Breakfast at the Exit Cafe by Wayne Grady and Merilyn Simonds and Ape House by Sara Gruen.

November 28, 2010

Canada Reads Indies Sneak Peek

Canada Reads Independently is revealed on Wednesday, though I offer a (not particularly telling) sneak peek here. What a stack though, you’ll just have to trust me. I am very excited, and pleased that my Fantasy Panel stepped up with such aplomb. I can’t wait to read these books, and I do hope you’re inspired to read a couple of them too.

Canada Reads Independently is revealed on Wednesday, though I offer a (not particularly telling) sneak peek here. What a stack though, you’ll just have to trust me. I am very excited, and pleased that my Fantasy Panel stepped up with such aplomb. I can’t wait to read these books, and I do hope you’re inspired to read a couple of them too.

The deal with Canada Reads Indies is this: last year, the CBC Canada Reads list disappointed me, so I lined up some bookish folks to choose me a new one. For me, most of the fun of Canada Reads has been less the week of radio debates, but rather the recommendations from out of the blue, and the reading of the books and discussions with other readers, and so that’s what I focused on for the Indies. And though my list last year (and this year) did/do feature some independent presses, the “Independently” of my title is more about reading on my own terms (though I loved it very much when others joined me).

The rules are very lax– I keep asking for novels, and the panel keeps throwing up short stories, but that’s all right with me because I love short stories anyway. If you want to take part, you can read all of the books or some, but please do get in touch with your responses (or links to your reviews posted elsewhere). I am going to start reading my five books in the new year, but you can get started any time. I will be finishing reading by the week of the CBC Canada Reads Broadcasts, and inviting readers to vote for their favourite of the five. I will also be following along with CBC Canada Reads and reading some of the books from their list, because it looks interesting this year. It’s not so much that I have a problem with CBC Canada Reads as that I just love the whole idea and want to manipulate and monopolize it– surely you understand?

Anyway, I hope to be reading not so independently, and that the titles revealed on Wednesday pique your interest. Looking forward to plenty of bookish conversation and debate unfolding over the next few months.

November 28, 2010

How one guy is

“Fiction isn’t about guys and girls, or any other convenient category by which we can divide the population into large groups, except in the minds of people who can’t actually read. Fiction, unlike political rhetoric, is never about the general case. It deals in specifics. A work of fiction is never “about pornography”; it is about its own story, carried by its own internal logic and adhering to its own internal rules. The story may depart from reality in any number of ways, but we can only say the writer got it wrong if the work fails as fiction. And fiction’s sole obligation, beyond being interesting, is that it be accurately observed and true to its own rules. Fiction isn’t about how guys are; it’s about how one guy is.” –AJ Somerset, “Mine Clearance for Dummies. Or, What Kind of Idiot Writes About Porn”

November 26, 2010

Wild Libraries I Have Known: The Nottingham Central Library

In 2002, overwrought and in disgrace, I ran away from home (for the second time in one summer) to live in England and work for a while on a working holiday-maker’s visa. I ended up in Nottingham, which was neither here nor there, quite the Midlands indeed, because I lacked the wherewithal and financial resources to take on a city like London. I had $400 in my bank account, which dwindled to nothing before I got a temporary job stuffing envelopes at a driving school. I was living in a bottom bunk of a dormitory at a backpacker’s hostel, where the bathroom tiles crawled under your feet, and everybody was having sex with everybody else, except that I wasn’t and, for once in my life, this was purely a matter of choice.

In 2002, overwrought and in disgrace, I ran away from home (for the second time in one summer) to live in England and work for a while on a working holiday-maker’s visa. I ended up in Nottingham, which was neither here nor there, quite the Midlands indeed, because I lacked the wherewithal and financial resources to take on a city like London. I had $400 in my bank account, which dwindled to nothing before I got a temporary job stuffing envelopes at a driving school. I was living in a bottom bunk of a dormitory at a backpacker’s hostel, where the bathroom tiles crawled under your feet, and everybody was having sex with everybody else, except that I wasn’t and, for once in my life, this was purely a matter of choice.

So you can see that life was a bit unsettled, that there was no centre to cannot hold and things had already fallen apart. The point then was to put it all back together, and the reconstruction began with my library card. I can’t remember the day I got my card, or how it came about, but I imagine that it had something to do with a mobile phone bill linking me a Nottingham address (however transient). And then suddenly, I had a Central anything, an axis for my tilting world, which was beginning to be righted again.

For our first date, which was on a Wednesday night nearly eight years ago, my husband and I met at the bus stop in the photo above, in front of the Nottingham Central Library. It was from the library that I signed out novel after novel because I had no money for books, and even after I had money for books, I didn’t stop my library habit. Sadly, the only novel I vividly remember signing out was Ash Wednesday by Ethan Hawke, because there was so much vivid about that time that it’s all sort of a blur, but I remember that I was always reading. I remember rushing down to the City Centre on my lunch breaks to use the library internet for a fifteen minute block (and how could my internet habits have ever been that? When did it change, and why didn’t I notice?). To check my email, send missives home, check out the Globe and Mail homepage to see what was going on back in Canada, to update my early-twenties dirty-laundry-airing blog. I remember using the library to do research for an article I was determined to write and to publish, except that I didn’t know how to write or get published, and now I use that point as a gauge between here and now just to determine how far I’ve come.

It’s trite but true– the Nottingham Central Library provided me with shelter when the rest of the world was anything but. It provided me access, connection, and a place to belong, and I’m not sure what might have happened to me without it.

November 25, 2010

The Difference of Value Persists

My essay “The Difference of Value Persists” is in Canadian Notes & Queries 80, on newsstands now, in which I write about Lisa Moore, Virginia Woolf, Barometer Rising, shipwrecks, placentas, Margaret Atwood, hysterics, and sock matching, and mean everything I say. The article before mine argues all the points I make in my piece, and this is one of the reasons that I love Canadian Notes & Queries. Also because it is the most beautifully designed magazine in the world right now, and I’m not even exaggerating.

My essay “The Difference of Value Persists” is in Canadian Notes & Queries 80, on newsstands now, in which I write about Lisa Moore, Virginia Woolf, Barometer Rising, shipwrecks, placentas, Margaret Atwood, hysterics, and sock matching, and mean everything I say. The article before mine argues all the points I make in my piece, and this is one of the reasons that I love Canadian Notes & Queries. Also because it is the most beautifully designed magazine in the world right now, and I’m not even exaggerating.

November 25, 2010

Bedtime Story by Robert J. Wiersema

I was afraid to read Robert J. Wiersema’s new novel Bedtime Story because it contains a book within the book, which fascinates me in theory but usually frustrates me when it comes down to actually reading the book(s). Also because the book within that book is a fantasy quest narrative, which is usually a very good sign of a book that’s not for me.

I was afraid to read Robert J. Wiersema’s new novel Bedtime Story because it contains a book within the book, which fascinates me in theory but usually frustrates me when it comes down to actually reading the book(s). Also because the book within that book is a fantasy quest narrative, which is usually a very good sign of a book that’s not for me.

I decided to read the book, however, in spite of my fears, because I have never quite forgotten how much I enjoyed Wiersema’s first novel Before I Wake. Also because it’s a story about a parent/child connection through reading, about the power of literature in childhood, and because Wiersema’s interviews at Kate’s blog and at Steven’s made it seem so interesting.

Christopher Knox is at an impasse– his marriage beyond repair, his eleven year old son at a distance, and he’s been struggling to write his second novel for so long that most people have forgotten he’d ever written a first. When he gives his son a book for his birthday, a used book, and not even Lord of the Rings which the boy had asked him for, it seems a typical misstep– the boy is disappointed, his wife once again has opportunity to reflect that Chris only ever thinks about himself. The book, however, proves surprising, transporting Chris’s son David into its fictional world, which is remarkable for a boy who’s always struggled with reading before.

The problem, of course, comes about when David is literally transported into the fictional realm, leaving his parents and medical experts bewildered by his unresponsiveness. Chris, however, is well-read enough to know that strange things can happen, and suspects that his son’s book is at the the root of what has happened, and so embarks upon a quest to discover the magic spell behind the text that has taken his son, to keep the book from enemy hands (including unscrupulous publishing types), and to find the key to the spell so he can reverse it somehow and return his boy to their metafictional reality.

At the same time, David is undergoing an analogous quest, crossing canyons and mountain ranges in search of the elusive “sunstone”. These passages were short enough that my interest rarely lagged, and made interesting by David’s awareness of his place in the fiction, and how he has to keep others from realizing that he is an imposter. Even more interesting, he is accompanied on his journey by the spirit of a boy who’d read the book before him and similarly fallen under its spell. Unlike the other boy, however, David’s journey continues because all the while his body sits empty at home, his father keeps reading the book, convinced (correctly) that continuing the story is essential to David’s survival.

Lots of interesting things are going on in the text. We are treated to no physical description of Christopher Knox, and his narration is first person while the others characters’ are third, the effect of all this being space for the reader to be enveloped by the story, similar to how David becomes the fictional Daffyd. The novel is also a bit too long, a twist too far, but is conscious of this– in the fictional realm, David remarks upon his fear that the story will keep going forever, questing for the sake of quest, and we can certainly empathize. Wiersema also takes advantage of fiction to make alternative realities possible– Chris’s wife’s Jacqui’s refusal to believe her husband’s theory of what has happened to their son begins to seem preposterous. The book’s magic is so solidly rooted in physical reality that all lines between realism and fantasy are blurred, and genre becomes any extraneous idea.

Bedtime Story is a novel to be enjoyed on multiple levels– a fast-paced thriller, ode to childhood reading, a testament to the power of literature and written word (which is always a kind of magic spell, however benign), a magical escape narrative, a heartening story of father/son relations, and there is murder, mafioso, and a mysterious library as well. It was truly a pleasure to get lost in this one for a while.

November 23, 2010

The Empire Within takes the QWF First Book Prize

Congratulations to Sean Mills for winning the Quebec Writers’ Federation First Book Prize for The Empire Within: Postcolonial Thought and Political Activism in Sixties Montreal (and thanks to McGill-Queens University Press for livetweeting the QWF Awards— next best thing to being there). Mills’ book was one of the biggest surprises of the 25 books I read in the running for the award– I had no connection at all to the subject matter, or the author, and I was initially intimidated by it being an academic book, am wary of theoretical constructs and non-fiction certainly isn’t my first bookish love.

Congratulations to Sean Mills for winning the Quebec Writers’ Federation First Book Prize for The Empire Within: Postcolonial Thought and Political Activism in Sixties Montreal (and thanks to McGill-Queens University Press for livetweeting the QWF Awards— next best thing to being there). Mills’ book was one of the biggest surprises of the 25 books I read in the running for the award– I had no connection at all to the subject matter, or the author, and I was initially intimidated by it being an academic book, am wary of theoretical constructs and non-fiction certainly isn’t my first bookish love.

But my lack of connection to the subject matter meant that the book was altogether absorbing– how could I ever have thought I knew anything about Quebec in the ‘sixties when my understanding of its history began and ended with the October Crisis? How could I ever have had an opinion on French/English relations in Quebec and Canada having never understood the disparity that had existed between the French and English up until the mid-twentieth century? Mills deftly weaves civil rights, women’s rights and French language/cultural rights together, and frames his ideas in post-colonial theory which (get this, it’s unbelievable) actually enhances our understanding of the subject matter rather than needlessly obscuring it for reasons of academic discourse. He also makes illuminating connections between activism in Montreal, and better-known movements in Paris, post-colonial Africa, and in the United States, complicated by the fact that the Quebec French were colonizers as well as colonized.

I learned so much from this book, and so enjoyed reading it, and vividly remember the sunny afternoon in which I finished it, on the second last day of July… Unlikely summer reading, I know, but the bookish life is full of surprises. Anyway, well done to Sean Mills and all the other prize winners, and many thanks to the QWF for asking me to be a juror.

(Click here for a free podcast of Sean Mills’ walking tour of 1960s’ activist Montreal).

November 23, 2010

Talking In Circles and Coming Full Circle: Talking About Talking About Motherhood

Marita Dachsel’s first book of poetry All Things Said & Done (Caitlin, 2007) was shortlisted for a ReLit Award. Her poetry has been published in many Canadian journals, in a recent chapbook, Eliza Roxcy Snow (red nettle press, 2009), and as part of Vancouver’s Poetry In Transit Program. Currently, she is working on a novel as well as finishing Glossolalia , her second poetry book, in which she explores the lives of the polygamous wives of Joseph Smith, founder of the LDS Church. After twelve years in Vancouver, during which she received both her BFA and MFA in Creative Writing at UBC, she now lives in Edmonton with her husband, playwright Kevin Kerr, and their two sons.

Marita Dachsel’s first book of poetry All Things Said & Done (Caitlin, 2007) was shortlisted for a ReLit Award. Her poetry has been published in many Canadian journals, in a recent chapbook, Eliza Roxcy Snow (red nettle press, 2009), and as part of Vancouver’s Poetry In Transit Program. Currently, she is working on a novel as well as finishing Glossolalia , her second poetry book, in which she explores the lives of the polygamous wives of Joseph Smith, founder of the LDS Church. After twelve years in Vancouver, during which she received both her BFA and MFA in Creative Writing at UBC, she now lives in Edmonton with her husband, playwright Kevin Kerr, and their two sons. Kerry: Marita, I think I’m beginning to change my mind. You see, I’ve been fascinated by narratives about motherhood since before I was a mother, and as I prepared to become one, I devoured the modern “ambivalent motherhood canon”.

But I’ve been reluctant to pursue such narratives myself. When I interview writers, I insist that their work is what’s important, and I avoid questions about writing and motherhood that would probably fascinate me as much. I worry that such questions would undermine the writers’ works, would undermine the individuals as artists, would undermine me as an interviewer and a reader. But I can’t shake a suspicion that these questions are important, that perhaps we just have to carve out a time and space for them. Or not. I’m not sure.

Did you feel any similar qualms as you embarked upon your Motherhood and Writing interviews?

Marita: When I first conceived of the Motherhood and Writing interviews, I had no qualms at all. I think that may have been because I really wasn’t aware of all the books written about motherhood and writing. I’m sure if I had dug a bit, I would have discovered them and not felt the need to start the interview series.

The interviews came from purely selfish place. I wanted content for my blog, but more importantly, I really needed to know how other writing mothers did it. My boys are twenty-two and a half months apart. When my second child was born, I panicked. I remember clearly breast feeding him while reading a biography of Margaret Laurence and having the terrifying flash that I would never write again. I knew I wasn’t as driven as Laurence was and couldn’t make the choices she had. My nascent career was over.

After my husband helped talk me down, I realized that of course my career wasn’t over. There were many, many writing mothers out there who were kind, loving, stable mothers. I wanted to talk to them simply to know how they did it. How does a mother balance all those things mothers do and make time to write. And I wanted to talk to women who were in various stages in their careers–from award winning to not yet published.

The project was supposed to be just for a year, but I’ve managed to draw it out longer, partly out of laziness and partly whenever I think it’s time to shut it down, I’ll get an email or a comment on the blog from some writing mother out there to thank me. It’s important, especially in those early difficult years, for those in the trenches to be reminded that they are not alone, that there are other women out there who are struggling, too. And, of course, that it will get better.

That said, recently I’ve begun to have qualms. Maybe it’s because I’m no longer in the trenches, or maybe because I’ve become sensitive that I might be contributing to the creation of a “motherhood ghetto”.

We would never ask a man how he manages to write while being a father, so why do we feel it’s relevant to ask a mother? Is it because there is an assumption that the woman is at home with the babies and that the man is not? And that if she isn’t, she should be? It’s insulting to both mothers and fathers. But I don’t know what I’d rather see–interviewers asking fathers what they ask mothers, or stop asking mothers what they don’t ask fathers.

So, yes, I am now quite conflicted. I hope that in the context of my interview series, the questions I ask aren’t insulting because that is the point of the interview. But I don’t think if I was interviewing a writer in another context, I would feel comfortable about asking about their relationship between writing and motherhood, unless the writer brought it up or it was clearly related to the writing.

Kerry: But yet, beyond domestic drudgery and “how does she do it?”, fascinating connections abound concerning art and motherhood. These interest me the most, and they’re questions that could serve to illuminate artists’ works and the experience of motherhood in general.

But there’s the matter of the ghetto, which you mentioned, and that, as Rachel Cusk mentioned in the introduction to A Life’s Work, that “motherhood is of no real interest to anyone except other mothers.” Why do you think this is?

Marita: I think there are a few reasons and they’re interconnected. The first that popped in my head is that it isn’t paid work, it’s part of the spectrum of “women’s work” (this label makes me want to scream, but I’m using it anyway). Also, because it seems anyone can get knocked up and therefore become parents (which anyone who has struggled with infertility knows how false this is), there is no understanding that parenting is a difficult job. I mean, how hard can it be, right? Turn on the t.v. and feed them and the job is done, right? Um, no.

It’s also invisible work. In public, unless you are a mother or you’re at a child/parent place (playground, school, etc.) you really only notice mothers when their children are in melt-down mode. Mothers are noticed when they are “failing”. I don’t know about you, but once I became a mother, I noticed how invisible I suddenly became.

But there is the inherent sexism of women’s work, too. In a patriarchal society, women’s work isn’t valued work. For mothers, the outcome is important–we want children to become obedient, hardworking adults–but how it’s done isn’t important. The idea of the loving mother is celebrated, but please keep that mechanics of that behind closed doors. We want to see smiling mothers and quiet children–not the day to day drudgery.

All these economic and feminist reasons I’ve been obsessing about since I became a mother, but this morning I woke up with might be the most basic reason: because it’s shop talk. Who likes going to a party and have to hear workmates talk about their jobs the whole night? Maybe it’s that simple with motherhood. People who aren’t mothers don’t care because they can’t relate, don’t want to relate. The politics and theories don’t interest them because they don’t affect them. (Although, I think the politics of motherhood does affect the wider society, however I’m sure the banking industry has an impact on my life, but I don’t really want to hear about either.) It seemed like such a revelation this morning, but now writing it down to you, it feels a little weak. What do you think?

Kerry: I actually love that idea, that it’s shop talk– it is! And it’s easier to think of motherhood being boring for that reason rather than motherhood itself being inherently boring. And yet, putting motherhood up/down there with dental hygienisthood and geography teacherhood isn’t quite right either, is it? Or perhaps it undermines what I’m most interested in about motherhood– how it changes how we understand the world, how we understand our bodies, other women, our own mothers. Issues of empathy, bonding.

I think that motherhood is mostly boring for a reason you mentioned– that it’s so ordinary. Everybody’s mother was a mother, and a lot of daughters will end up being one too, and quite a few of them even managed to go about it without waxing ad nauseum on the subject. Without having conversations like these.

Do you think it’s a phase, this obsession with motherhood? You’ve mentioned that you’ve moved away from it as your kids grow out of babydom. Was it a necessary phase? A useful phase? And how do we make it about more than navel-gazing (which so much online conversation about motherhood, I regret, never manages to do)?

Marita: On a personal level, I think it is a phase, at least at this level of intensity. I wonder if it is a product of our society, this need to analyse it so much? I can’t imagine mothers of our grandmothers’ generation dissecting it so much. Is it because we generally have children at a later age? We’re having less children? We’re not as physically (and perhaps emotionally?) as close to our families as generations past, so it’s more foreign to us? So many questions I don’t know how to answer.

For myself it was both necessary and useful. I was the first of my close girlfriends to have a baby and other than my small, immediate family, I have no relatives in North America. My husband had some friends with children, but I wasn’t in his life during their early years. Despite always knowing I would have a family, I had no idea what those early years of motherhood would be like. I became obsessed. I think that’s normal.

I learned so much about motherhood, about myself. I especially needed to see my position as both a writer and a mother reflected back at me. It’s almost silly now to think how desperate I felt, how much I needed to see that yes, I could be both a writer and a mother. The day-to-day life of writers and mothers can be terribly solitary. I needed to know that I wasn’t alone.

How do we get past navel-gazing? I don’t know. Partly we need it to be navel-gazing, because we need to see ourselves, our situations reflected back to us by others, and how can we do that if we don’t talk about ourselves?

Motherhood is incredibly transformational, especially for those of us lucky enough to have been able to conceive, carry, and birth our children. The physicality of pregnancy and birth is so intense, so raw and life-changing. Birth changes you. You battle through this profound visceral event, and on the other side of it, you have a new title, a new job: mother. It’s crazy. Of course we’re going to talk about it, analyse it, try to make sense of it.

I’m curious about your desire to take beyond the navel, that’s my impulse too, but I’m not sure what the forum should be. Are you specifically talking about the online world?

Kerry: Oh, I’m talking about the whole wide world, but online in particular. I think that’s what I liked about your motherhood and writing interviews– that they were looking at motherhood in the context of something bigger, and that was so interesting to me. Perhaps I also needed a reflection of mother/writers, to know it was possible.

Whereas the whole mommy blog circuit was just depressing, uninspiring. Once I’d grown accustomed to being overwhelmed by my crazy blown-apart new life, I didn’t so much want that experience affirmed, as some bloggers delight in doing. Maybe I am unusual in this, but I wanted to believe in the possibility of something better, something more. That I wasn’t limited to this entrenched idea of motherhood– of being forever harried, depressed and stretched to the point of exhaustion. I mean, of course it was nice to know I wasn’t alone in the hardships, but when life is really awful, how much do you really want it reflected back at you? And how far can that kind of reflection really take you?

If we’re talking beyond navels, I’ve been really inspired by the work being done through the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement (MIRCI, formerly the Association for Reseach on Mothering). Their book Talking Back to the Experts was a real tool of liberation for me as a new mother, and I also appreciated Mothering and Blogging: The Art of the Mommy Blog, which gave me such an appreciation for what blogs about motherhood have done in particular for marginalized or isolated mothers. These books had me understanding my own experience in a wider context, and also addressing issues of feminism and motherhood and how these ideas support and contradict one another. That motherhood was a job that required a great deal of thinking, learning and understanding. Worthy of an area of academic study, even– I liked that.

I wonder if the level of analysis and need for understanding you so astutely addressed is particular to artists– writers tell these stories over and over again, but would an architect fixate on the narrative quite so much? Does our artistry give us the means to engage with motherhood as we do, or do you think it happens to everyone?

Marita: Thank you, I’m glad you liked the interviews! I think you nailed how we can take the discussion of motherhood beyond the minutia–by talking about it in relationship to something else. Perhaps that is why we talk about it so much now. Our mothers’ generation was fighting for our rights to be anything we wanted to be, and now, our generation is figuring out how to negotiate our place within so much choice and what that all means.

As a huge, sweeping generalization, there seems to be two types of mommyblogs. The negative, complaining ones you mentioned and then the ones on the other end of the spectrum, where everything is perfect and idealized. No chaos, all domestic bliss. It’s hard to be in that place, too. Neither options feel honest or a reflection of my reality. But I must to admit that I still read a couple regularly, and one of them is the “perfect life” kind. (However, if she didn’t post every day, I probably would stop that one, too.) I can’t read the negative ones at all.

Your last question is a hard one. My hunch is that most mothers want to reflect on motherhood, at least early on and I think that’s why mommyblogs are so popular. That said, artists have the creative vocabulary to fixate, which many people do not, but more importantly, it’s our job to fixate. A new mother who returns to work at her architecture/accounting/law firm has other work she’s paid to do, but as artists, one of our jobs is to obsess. So many artist-mothers that I know try to work from home at the same time as trying to be a SAHM. Both are full time jobs, so it makes sense to me that this obsessing ends up being reflected in our work to some degree. Writers specifically create narrative, so of course we’re going to examine and dissect how this new character is changing our personal narrative arc.

I believe that every experience we have somehow influences our work. I haven’t read Emma Donoghue’s Room yet, but my hunch is that it would have been a very different book if she wasn’t a mother. You’ve read it. What do you think? And do you think you can tell if an artist is a mother? Would you want to?

Kerry: I think an artist can imagine her way into motherhood, and I say this with assurance because I’ve read Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin. I remember reading the novel The Almost Archer Sisters by Lisa Gabriele too, and being stunned to discover that Gabriele wasn’t a mother– it’s a funny, popular novel, but her depiction of mothering a disabled child is stunning. I asked Alison Pick if she’d made changes to how she wrote about parenthood in her novel Far To Go after her daughter was born, and she said she’d pretty much got it right the first time (and she did).

What was remarkable about Room to me was not how “right” Donoghue got my experience, but that she’d actually managed to articulate aspects of my experience I hadn’t before been conscious of– which is really incredible. I’m at home all day alone with Harriet, and I remember as I was reading that everything I said and did was taking on a new resonance. I had never realized (perhaps because Harriet is still so young) how much a mother constructs her child’s universe in the various real-world Rooms in which they find themselves– the womb, the empty house alone all day.

I think if Donoghue hadn’t been a mother though, Room would have had a different kind of emphasis. I recently read James Woods’ review of the novel in the LRB, and he wrote about its lightness, its readability, the cutesy focus on Jack– and how the actual story that inspired the novel would not have such a rosy tinge. Because of her focus on the mother-child bond, Donoghue was able side-step a horror story, the fact that an actual mother probably would not construct such a fair and happy world for her child, would have neither the tools nor the capacity to do so. Room is a fairy-tale, really. Perhaps as a mother Donoghue was unable to look the real situation in the face (and I can’t blame her). Her story is a hypothetical one rather than a particular one, and there is safety in that.

And I must say that you’ve just answered my question, Marita! Well done. You ask, “Can you tell if an artist is a mother?” and I think, perhaps, one can’t. (Though sometimes, with bad artists, you can tell when they’re not a mother cough cough Christos Tsiolkas). Which means that my longing to ask or not to ask questions to artists about motherhood is kind of beside the point of the art. Has more to do with my own life and my own interests at the moment than art itself. (Ah, sweet navel, nice to gaze at you some more…) Which doesn’t mean these questions don’t matter, and can’t be incredibly useful/interesting in some respects. But perhaps my aversion to dwelling upon them comes from a rational place?

I think, Marita, that we’ve come full circle, and in a satisfying way. Do you think so? Can you tell if an artist is a mother?

Marita: Yay! I’m glad I helped you find your answer. I agree, I don’t think you can tell if an artist is a mother, and one wouldn’t want to. There are things that only some mothers can know, like what let-down feels like, or when your water breaks, but those details are so small that they are insignificant when it comes to the creation of art.

Someone once told me to not write what you know, but write what you want to know. This seems rather relevant to this conversation. I’m more drawn to writing about certain subjects and themes at the moment (my polygamy project) because of motherhood, but I know I won’t only write about those for the rest of my life. As artists, it’s what interests us in the moment, and for some it is motherhood.

I do think, however, that we still need to have conversations amongst writing/artist mothers, even if it is simply to compare navels and say, yes, that’s normal too.