June 14, 2023

Author Website

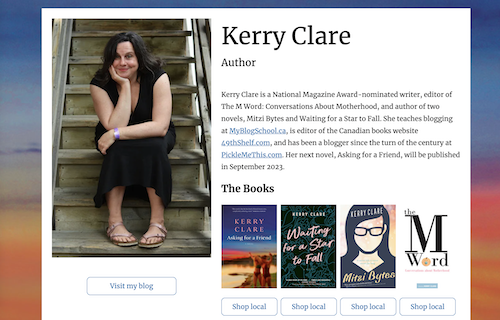

I’m very excited to announce, nearly ten years after the release of my first book, that I finally have an author website. I’m sharing it here in the unlikely case that someone reading my blog didn’t KNOW that I am an author (perhaps you are sidebar-blind?). If my next book does well, let’s give this author website ALL THE CREDIT, okay?

June 14, 2023

Gleanings

- We forget that we are also entitled to acceptance. We are entitled to evolution. We are entitled to true healing, which often means escaping the initial story and writing a fresh one that is less about our pain and more about the full spectrum of experience (you notice I didn’t say heroism…another trap of a story).

- In my writing life, in my writing career, it felt like waiting was the primary state of being. What if the waiting is over and I’m just floating on my back down a beautiful wide peaceful river?

- There used to be a time, so long ago that if you’re under a certain age you likely won’t remember, that air travel was glamourous.

- I’m often challenged regarding my sense of what’s “on the way home.” More than an actual bucket list, I’ve envisioned a life free to swerve and bend the map and the calendar for stops at beaches, cute mountain towns, hikes, and retreat centers.

- Due to down time whilst recovering from some injuries, today was my first outing in a long while, and Wheatley welcomed me back with open arms. Well, at least with wide-spread branches.

- I’ve been re-training my brain these last couple of years to remember all the things I LOVE, and to try and spread that love. But once in a while it’s good to CONSIDER THE OPPOSITE and to also have that comedic distance. So it makes me laugh a bit to consider what I hate once in a while.

- To allow the whole of it, be a part of it, to not see things as right or wrong, good or bad, better or best, but to make room for all of it. To delight in difference, be open, and listen for the next true for us decision, willing to shift and change as it comes.

- Lately, therefore, I’ve come up with a little game I call “Poetry Serendipity”: every time I go up into the stacks of the university library, I take different routes on my way to and from whatever section I am specifically visiting and, as I wander, I scan the shelves for names I recognize or (more random and risky, but also more fun) for those tell-tale slim volumes that you just know must be poetry collections.

- Some mornings I don’t look up as I walk down to the water. But this morning I’m glad I did.

- It’s at this time of the year that my camera roll is chock full of flowers. The peonies on Brunswick, the poppies on Howland, Irises, lilacs, and wisteria. Some flowers are easier to photograph than others. The translucent quality of a poppy’s petals is hard to capture when too much sunlight is pouring through it. All the beautiful detail gets erased by the sun.

- But that does not begin to describe what I am leaving behind. My head is swirling with so many little moments. The ringing of the doorbell and a neighbour on my doorstep in tears, asking for a hug. Going to check the mail and finally returning two hours later, having stopped for several conversations. Laughing as a friend climbs through a window because her three-year-old has locked her out. Remembering my children avoiding neighbours on Hallowe’en because their displays were just too creepy. Fighting the removal of the basketball hoop that neighbours felt was too noisy. Grateful for the flowers and hand-drawn cards left at our door by children when our old dog, Tucker, died.

- think scalpel, not sledgehammer

June 12, 2023

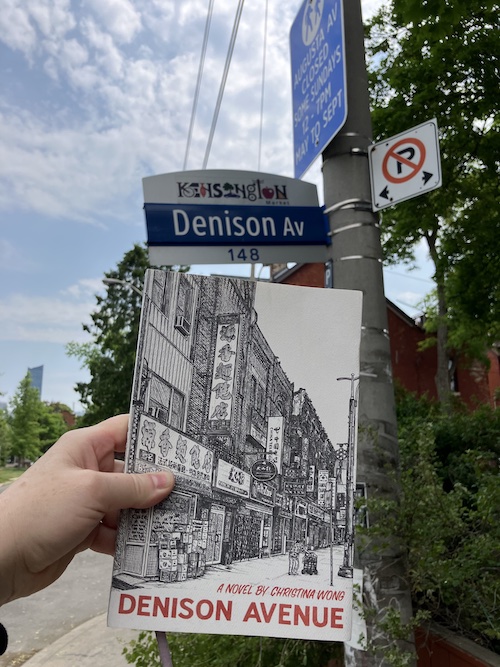

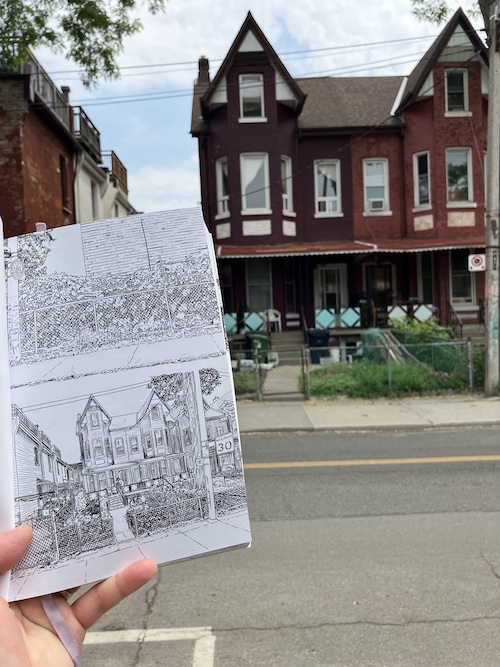

Denison Avenue, by Christina Wong and Daniel Innes

The nature of cities, of course, is that cities change (I wrote about this in my 2017 essay about Ann-Marie MacDonald’s ADULT ONSET, a book that maps on to this one in surprising and interesting ways), but anyone who loves that city or calls it home is going to struggle with that, or maybe that’s even just the baked-in nostalgia that comes from being alive. I’m well accustomed to stories and images of “Old Toronto,” the kinds of photos that get shared in Facebook groups with names like “Long-Gone Toronto,” the kinds of images that Kamal Al-Solaylee writes about in his 2014 essay “What You Don’t See When You Look Back,” about the whiteness of these vintage scenes: “The pictures depict a world where only white people roamed the streets or were allowed into the frame. I can’t help but conclude that the friends who post them would have preferred it if Toronto had stayed that way: small town, white, exclusive and free from people who look like me.”

But in their new book, DENISON AVENUE, Christina Wong and Daniel Innes are doing something different, and in more ways than one. First, the book itself, which is double sided, one side telling the story gorgeously in Wong’s prose and poetry fragments, and the other with panels showing Innes’s drawings of Toronto “now and then,” now being about ten years ago—when Honest Eds was sold and the Kromer Radio property on Bathurst was going to be developed into a WalMart—and then during the years before it with a thriving Chinatown and Kensington Market, before these areas had become ripe for development and working class people could live a decent life downtown.

Within Innes’s contemporary drawings, a figure appears pushing a cart along the sidewalk, picking up cans and bottles along the way, a figure I didn’t even notice the first time I flipped through the book, which is the point of the book, about what remains invisible, and who gets to be seen, and heard.

The woman in the drawings is Wong Cho Sum who immigrated to Canada in the 1960s and lived in a house with her husband on Denison Avenue until his death (when car sped past the streetcar doors on Dundas Street). Together they had built a steady and comfortable life with strong community ties, but in the wake of her husband’s death and the city’s changes (which are not bemoaned just because it’s change, but because these are changes that make life more difficult for Toronto’s poor and marginalized people, something Cho Sum has seen before as the city’s previous Chinatown was forced to move west when the area was redeveloped as New City Hall) she finds herself unmoored from the world around her.

To fill her days (or perhaps I mean her evenings and early mornings!) she begins collecting cans and bottles around local neighbourhoods, developing a route up and down streets that are familiar to me.

What I loved about this book was how it told the story of a changing Toronto from the perspective of a person of colour, a person who speaks very little English (in the book, Wong writes her dialogue in the Toisan dialect), which is a perspective I’ve never heard before. And similarly, though elderly women collecting bottles and cans are as ubiquitous in my neighbourhood as they are in Innes’s drawings, I’ve spent very little time considering these women’s perspectives, what brought them here, why they’re doing this—for Cho Sum, it’s to earn a bit of money, and give shape to her days, and for exercise. In so many ways, for me, Denison Avenue was absolutely a revelation.

And it was also just a tremendously moving story of strength and resilience, of love and courage, and friendship and community. (There is a swimming scene!! I just adored it.)

The nature of cities, of course, is that cities change, but in Denison Avenue, Wong and Innes manage to capture a unique view of the city as it was for just a moment, all the while making their readers consider what the city might become if we think about what it’s true heart is, which is to say the people who live here.

June 12, 2023

PEI Mini-Break

I try not to work too hard to ensure absolutely that my children get everything divided right down the middle, because life isn’t like that, and their needs aren’t always 50/50 either, and who has the time for that? But there are two instances in which it’s been important to me that Kid 2 gets what her sister had—the first was their baby books, and I remember scrambling to add to Iris’s in a sleepless exhausted haze quite convinced that my effort would be worth it once she was old enough to appreciate, and how right I was. And the second instance was the 10th Birthday Trip, a tradition we began with a long weekend in Manhattan when Harriet turned ten—it was magic! And four years later, especially after everyone missing out on so much, I was committed that Iris get her mini-break too, even if the cost of travelling has skyrocketed.

And thankfully, a solution arrived. A very cheap flight to the magical land of Prince Edward Island, where we were lucky to have cousins host us for three nights and even lend us the use of their car. It was amazing, and while this was a different kind of island than we visited before, it was no less exciting to experience and also there was a very good bookshop.

June 9, 2023

Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden, by Camille T. Dungy

With the essay collection Guidebook to Relative Strangers: Journeys Into Race, Motherhood, and History, Camille T. Dungy became one of my must-read authors, although I might have read her follow-up Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden anyway on the basis of that gorgeous cover (and oh my goodness, wait until you see the inside covers!!). Soil is a book about metaphors, but also about the thing itself and, to begin with, that this is the garden that Dungy designs and brings to life in the yard of her suburban home in Fort Collins, Colorado, a place where the propagation of native plants and a wild-looking garden is in defiance of home owner association standards about such thing as grass lengths, and Dungy and her family are part of the reason that culture begins to change.

This is a memoir about the labour (and setbacks) in cultivating diversity in our gardens, and beyond them. It’s also a story of receiving a Guggenheim grant to write a book whose progress is stopped up by the Covid-19 Pandemic and a ten-year-old child whose home schooling requires supervision. It’s about being a Black person and a Black mother in America in the wake of the 2016 election, whose fallout in a continuation of centuries of struggle and oppression, and what it feels like to be confronted by deaths of other Black people, those names like beads on a string over the past decade and more—Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd. Like a rosary.

She quotes her father’s response to a (white) reader’s question about how Dungy could consider herself an environmental writer when she spends so much time writing about African-American history. Her father (Dr. Claibourne Dungy) answers, “For us, there is no separation between the environment and social justice.” It’s not one thing or another, but instead everything connection, our environment home to the world we choose to build here, and also to the natural elements over which we have no domain (or at least cannot even imagine we do) and here Dungy writes of wildfires across the state of Colorado during that already miserable plague year, where neither indoor air nor outdoor was safe to breathe in the company of others, and disaster seemed perpetually just shy of the doorstep.

This is a book rich with love, wisdom, and humour, a book about neighbours, about community, about marriage and love, about trying to save truckloads of soil from blowing away in a windstorm. It’s about climate change, and weather, and history, and botany, and place, and travel and belonging, and longing, and grieving, and persisting. It’s about faith.

“Faith is the belief in things not seen. Or it is the hope that what has not yet materialized might, someday, manifest… One of the hallmarks of faith is to believe in a promise and—though the promise has yet to come to pass, and may never in my lifetime be fully fulfilled—to find a way to carry on. To discover and honour what HAS come to fruition.

I dig up a lot of awful history when I kneel in my garden, But, my god, a lot of beauty grows out of the soil as well.”

June 8, 2023

AFAF Mood Board: Part Three

Time for mood board number 3 for ASKING FOR A FRIEND, coming September 5 from @doubledayca. This instalment takes us through 2006-2007 as Jess and Clara find themselves back on the same continent for the first time in years, but worlds apart in so many other ways, Rihanna’s “Umbrella,” playing low on the radio in the background: “Said I’ll always be your friend, took an oath gonna stick it out to the end.”

Save the date for a Toronto launch on September 6!!

June 6, 2023

The Opportunist, by Elyse Friedman

There are all the book whose blurbs promise you they’re unputdownable, and then they were the books that are just impossible to put down, and Elyse Friedman’s The Opportunist is both. It’s the story of a woman estranged from her wealthy family whose brothers only get in touch because they want her to help get their elderly father’s fiancee—his twenty-seven-year-old nurse—out of the picture and preserve their inheritance. A single mom of a disabled daughter who ekes out a living working at a domestic violence shelter, Alana agrees to head back into the family fold because she’s promised enough money to buy her daughter an accessible mini-van. When she arrives at the family estate, however, her father’s gold-digger girlfriend turns out to be nothing like what she’d been led to expect, and more savvy than anybody is giving her credit for. Loyalties, much like the ground beneath these characters’ feet, are ever shifting, and just when the reader thinks they’ve got a handle on the situation, the next chapter reveals another unexpected twist, not to mention a whole new level of depravity. I’ve never seen Succession, but I think this excellent novel might fill the void its finale has left in the world of its fans. Taut and compelling, not to mention VERY FUNNY (the line about the orangutan!), The Opportunist is a glorious fuck-you to the patriarchy, and ends on a note as surprising as it’s glorious. Put this on your summer reading list right now.

June 5, 2023

Change Your Story

Ten years ago TODAY, Iris was born, and this photo is of my first glimpse of her, snapped by Stuart, who knew how upsetting I’d found it to never see Harriet until she was cleaned up, wrapped in a blanket and wearing a hat. Because without having seen, it felt impossible to me, that she’d come from my body, how one thing had turned into another. Which was part of the reason I tried so hard to have a natural birth with my second baby—not JUST because I wanted things to be different (though I did!) but really because I wanted to understand and to keep whole the many things that ended up broken the first time. All along conscious that maybe I was failing to learn the lesson I’d failed that first time, which is that these are stories that refused to be controlled and managed , and some submission is required. Which sounds TERRIBLE because it is, and so I’m so happy to report back that that is only part of it. Nope, I sure didn’t get my natural birth experience, but what I got instead was the chance to apply what I’d learned from things being so hard the first time to have an altogether better experience the second time around.

This photo was part of that, this magnificent image that will never stop blowing my mind, just like the seconds old baby at its centre never has either. I can’t possibly express what it meant to me to be able to have a new baby and to be happy during those tender blurry early weeks. How I’d envied other new parents who’d been there, secretly wondering if such a thing was possible. But it was, and it was us, and that extraordinary time (my husband took three months parental leave so we could it all together, our eldest was four years old, we’d been very methodical in orchestrating a situation in which I would be supported and not left flailing like I’d been the first time) was one of the greatest gifts of my life. It’s central lesson being that while some submission is required, we also do (to quote a line from Iris’s favourite musical) have the power to CHANGE OUR STORY. And oh, how I love this story so much.

May 31, 2023

On Momfluence

I was still five years away from motherhood the first time I came under the spell of momfluence, but of course 2004 was a very different time. I was living in Japan then and a blogger I followed about expat life in Japan took part in some sort of exchange with another blogger who was an American mother of three who lived in Malawi where her partner ran educational programming, and I was hooked. On her blog, which was called “Lucky Beans,” she used to have a blog feature called “Corners of My Home” where she could give readers glimpses into her family’s private spaces, which were usually littered with stones and pebbles collected in her youngest child’s pockets. I think her approach was Montessori-based and I was impressed by her household’s toy organization, a bin for everything and everything in its bin. None of the toys in her home were plastic, I think for Montessori reasons, but indeed this also had a particular aesthetic, and I fell in love with it. “When I have a child,” was the thing I thought, “this is the kind of mother I want to be.”

And I kind of was! There is no twist to this story. The internet has always been useful to me for aspirational purposes, but not in an aspirational aspirational way, if that makes any sense. It was never about striving for something unattainable, but instead putting an idea in my mind of an approach to parenthood that would suit my circumstances. And my aesthetic—I still hate plastic toys. But it was also less about aesthetics than practicality—I live in a small apartment and have never had that much extra money. Having less stuff and organizing it neatly just made sense, and also for the planet, because I think of all the exer-saucers that are going to outlive us all.

It helped that she wasn’t trying to sell me anything (like I said, this was 2004; she didn’t even have an Etsy shop!) and even if she was, I wouldn’t have been able to buy it. And indeed there was definitely an element of performance to her online identity (my favourite was the time she went away for a couple of weeks, and her husband took over the blog, temporarily changed the name of “Lucky Beans” to “Tough Beans: Dad’s In Charge,” and showed us a much less idyllic view of their domestic life) and surely there is one too to the fact that I’m writing this at all, and letting you know that even when my children began to acquire My Little Ponys, they were secondhand.

It’s complicated, which is the central thesis on Sara Peterson’s new book Momfluenced: Inside the Maddening, Picture-Perfect World of Mommy Influencer Culture. I have no idea how I would have been a parent before the internet starting throwing inspo my way, or how my own mom helped me figure out science projects, birthday party themes, or Halloween costumes without the help of Google (and to be fair, some of my Halloween costumes were pretty shitty). How performance is baked in to my experience of motherhood, as my blog documented my pregnancy, my bumpy intro to the mothering life, and then social media came along to help me track my children as they grew and grew and grew. Without online life, I would likely be less annoying in many ways, and I might even be less smug about my children’s wooden toys, and would they even have wooden toys at all if Lucky Beans hadn’t convinced me?

I think being an online creator, as opposed to a consumer, even as someone whose online platforms have a negligible following at best, has helped to keep my relationship to the mamasphere more positive and inspiring than soul-destroying; it’s broadened my world instead of depleting it. I wonder if it helped too that I didn’t join Instagram until 2016, by which time I’d found my feet as a parent, was not so lost in newbornland. And while I did recognize myself in some of Petersen’s profiles (I think we went apple picking twice and everybody hated it, and we don’t do that anymore; omg, I also just remembered the cookie bunting I tried to string at my daughter’s sixth birthday, which was definitely for the ‘gram, but I cut the holes wrong, and they fall fell together on a clump on the string before the whole thing fell on the floor) it has helped me that the ways I’ve been inspired by others’ online mothering has been alligned with my own inclinations anyway, that I’ve never been very interested in doing anything that I don’t want to do. (I don’t like crowds, for instance, so lining up for that iconic photo that everything else is doing is really not likely to happen.) I really do think that Instagram has inspired me to look for the spots of beauty in my life, and to try to cultivate more of that, which works to my benefit—it means there will be a bouquet of bright coloured tulips on table all summer long.

But I do wonder what the costs might be. What would my family photos look like if I hadn’t been influenced by other people’s poses? How would I be a different parent if I could be more focussed on the immediate, on the moment, rather than thinking about how it all might look from the outside, how best to capture the light. But see, would I even notice the light then? And I always notice the light. If a string of bunting hangs in the kitchen and no one is there to put it on instagram, does the bunting even bunting? (But it does! I see it every day! And oh, look at the light. Let’s take a photo. Let’s capture time for a moment, sunlight shining through the dregs of a jam jar like a Mary Pratt painting.)

May 30, 2023

Gleanings

- if you spend a lot of time imagining a person’s reaction to a present it’s probably a sign that the present is mostly about you, anyhow.

- And again and again I keep revelling in the reaction of people as I say, “I appreciate you.”

- If you’ve ever wondered what booksellers have in their beach bags, wonder no more!

- and though overall I am still disappointed in it as a revision of Dickens’s novel, as its own novel Demon Copperhead is, I think, actually pretty good.

- I want the names of everything. The bees in the first tomato flowers — Bombus vosnesenskii, the yellow-faced; the Swainson’s thrush I heard as I went out for my swim–whit, whit; the long roots of Rumex acetosella, sheep’s sorrel, I keep pulling from between the pavers in the greenhouse. The rough-skinned newt, the Pacific tree frog (sometimes the chorus frog, once Hyla regilla, now Pseudacris regilla, though nothing about the frog has changed), Rosa ‘Félicité Perpétue’ by the front door, where the tree frogs lie low in the damp earth.

- As my children and I stood at the intersection of Dupont and Davenport, it literally felt like it was raining petals. I resisted the urge to pull out my phone and video the whole wild scene. Some things are better experienced with the eyes.

- But the thing I ran into when my kids left me, once again, with a basket of overpriced strawberries on their last legs — fruit they’d asked me to buy but then mysteriously lost interest in eating when it was presented to them at breakfast — and I decided to instead turn strawberries into strawberry-ade, so to speak, was that every lemonade recipe I’ve already published contains steps I lacked inclination to do.

- But I am most intrigued by Radha’s question in the book, describe the scent of your mother.

- This, my friends, is a book that will pull back a curtain and show you something incomparably lovely, and then while you are gazing at it in awe, punch you in the stomach.

- Critique works when we’re playing together, when we like and admire each other’s unique gifts, when there is an equal exchange of energies.

- Although helmets have ruined that feeling in my hair, I felt the cool breeze on my face as I tooled around the quiet streets of Weston. There’s not much left of that farmgirl flying fearlessly over gravel. I’m a bit wobbly and weeks from feeling confident on roads with actual traffic but it felt terrific!

- It is a testimony to Donna Tartt’s brilliance as as a writer that when I was in the book I rarely thought “There is no reason for sane people to behave like this,” but later I would be mulling it over, or trying to describe it why I liked the book so much to Mark, and couldn’t string it together.

- The world is full of questions, but art doesn’t hand you the answers. It makes an offering.

- As ever, the only real secret to creativity, is to work, to be creative, to be obsessed, to look at art, to read. You never hear of any successful artist talk about their secret being to go to cocktail parties, or art shows or poetry readings. (Though those can all be lovely things).

- That’s the thing about wonders. They’re fleeting, ever changing. Nothing stays the same, especially me. But when I look, I can find one or two, or seven delights. Today’s wonders bring me joy or peace.