September 7, 2011

Upon my word…

“‘…The women one meets– what are they but the books one has already read? You’re a whole library of the unknown, the uncut.” He almost moaned, he ached from the dept of his content. “Upon my word, I’ve a subscription.”‘ –Henry James, The Wings of the Dove

September 7, 2011

September is insane, no?

September is insane, no? And I don’t even have children going back to school. (I do have one child who has recently gone onto a playschool wait-list for next September however, which has been a more emotional experience than one might expect. It looks like I’m going to be one of those parents after all). Anyway, for some reason, I decided that now would be the best time for me to read Henry James’ The Wings of the Dove, that reason being that I’d come to James on my to-be-read shelf, and to skip him for something lighter would be a violation of book selecting rules, and also an indication that I’d probably never read Henry James’ The Wings of the Dove ever.

September is insane, no? And I don’t even have children going back to school. (I do have one child who has recently gone onto a playschool wait-list for next September however, which has been a more emotional experience than one might expect. It looks like I’m going to be one of those parents after all). Anyway, for some reason, I decided that now would be the best time for me to read Henry James’ The Wings of the Dove, that reason being that I’d come to James on my to-be-read shelf, and to skip him for something lighter would be a violation of book selecting rules, and also an indication that I’d probably never read Henry James’ The Wings of the Dove ever.

So I’m reading it. It’s pretty wonderful. I do sometimes wonder if there aren’t ways Henry James could have expressed his ideas with a bit more clarity, but I’m enjoying the book much more than I liked What Maisie Knew when I reread it a while ago. Progress is slow, and I’m about halfway through. Also finding that avoiding reading James is enabling me to get a lot of other work done, plus I’m reading Granta 116 and Stephanie Bolster’s remarkable collection White Stone: The Alice Poems.

Anyway, the day after I started reading The Wings of the Dove, four books came in for me at the library, I got two freelance review jobs, and now I also have to read Rebecca Rosenblum’s new book The Big Dream in the next very little while because I’ve been honoured with the task of conducting an interview with her at her book launch on September 20th. The Canadian Bookshelf wheels are also spinning madly at the moment, because it’s publishing’s big season and so much is going on. Case in point, the three literary events going on tonight, each of which I’m longing to attend, but there will be just one, alas.

The opposite of all this, of course, would be a life devoid of everything I’ve ever wanted, and so you won’t hear me complain. Let’s take up a bit more Henry James now while the baby’s asleep, and my tea has just cooled enough to drink.

September 6, 2011

My Library Matters to Me

I entered the “My Library Matters to Me Contest” because there might be someone left on earth to whom I haven’t yet told my tales of library love. The contest is run by the Our Public Library campaign, in defense of Toronto’s public libraries. If I am chosen as one of the winners, I’ll get to have lunch with one of the participating authors, which doesn’t bode well considering my record with author contact. (What if Margaret Atwood greets me with, “We meet again,” and then asks me why I’ve stopped wearing a visor?)

I entered the “My Library Matters to Me Contest” because there might be someone left on earth to whom I haven’t yet told my tales of library love. The contest is run by the Our Public Library campaign, in defense of Toronto’s public libraries. If I am chosen as one of the winners, I’ll get to have lunch with one of the participating authors, which doesn’t bode well considering my record with author contact. (What if Margaret Atwood greets me with, “We meet again,” and then asks me why I’ve stopped wearing a visor?)

Anyway, the reason I’m telling you this is because I would very much like not to win this contest in order to save myself a lot of social awkwardness. And the more people that enter, the less chance I have, so won’t you help a girl out and enter too? Because surely your library matters to you. The deadline is Friday, so you’ve still got time.

September 6, 2011

On the Giller Long-Long List

I wrote a post last winter called “Ephemeral, yet eternal” in which I celebrated the good-but-not-great book. I wrote: “That [such a book] didn’t win prizes is not to say that it’s not a worthy book, but that a worthy book didn’t win a prize is also not to say it was robbed. Prizes are not the sole determinate of worthiness. And I’ve been thinking of this lately, considering the number of books I read that are considered unrecognized because they’re not short or longlisted by Giller and the like. The notion of the “snub”, the entitlement behind that notion, as though everyone deserves to be a winner. As though prizes were handed out on an assembly line, when really sometimes it’s the books that seem to be produced that way, so can you really be surprised when yours isn’t a winner?”

This year, as part of their mandate of bringing the public closer to the judging process, the people at the Scotiabank Giller Prize published a list of all the books that were eligible for the award. I had a bad feeling about this immediately. “My book has been nominated for the Giller Prize!” was how the spin went on a few posts on my Twitter feed, and it made me squirm with embarrassment, because of course the books hadn’t been. Books were on that list because they’d been submitted by their publishers for consideration they’d been published in Canada within the eligible time period for submission. (Thanks to AJ Somerset for his correction.) I’d read a few books on that list and some were terrible. Some others were the good-but-not-greats I’d been talking about earlier. One was a non-fiction book, and therefore not even eligible to be there in the first place, which goes to show how much screening had really gone into the submission process. (Some were wonderful books. A few of those have even made it to the longlist, which looks like a really interesting one.)

My problem with this is that there are 120-some writers who this morning were made to feel like they’d lost something. Now some of these writers might have felt this way anyway, but this time they were really set up to have done so. That they had their chances at the Giller Prize publicized, when some of them really never had that chance in the first place. To the others who did have the chance, I suppose, it’s just proved mainly a disappointing exercise, because I bet they didn’t get too many book sales out of the experience (except for those lucky writers whose names happened to start with A or B and showed up on the front of the website).

Awards-culture has its benefits, it does. I’ve discovered some wonderful books because of it, so many books have been sold on its coattails, and it’s a fantastic chance for unknown writers to take centre stage (Hello, much of the Giller shortlist from last year!). But the downside is that awards continue to be the standard by which success is gauged, even when those of us who’ve read widely know that, speaking critically, this is not really the case. Because a) terrible books win awards and b) really wonderful books don’t. This happens all the time.

And yet regardless, there is this assumption of entitlement. When a longlist is revealed, the first thing so many authors think is, “Why aren’t I up there?” An author who publishes a good-but-not-great book is made to feel like he has failed by not being nominated for prizes, even if that good book is a real harbinger of wonderful work to come. (And sometimes even when it isn’t.) Even if that good book has connected strongly with so many readers who are looking forward to see what he does next. (And sometimes even when it hasn’t.)

There aren’t enough prizes to go around. If there were, they would cease to be prizes. Very few books are truly extraordinary. And prizes are subjective, by the way. They matter, but they don’t matter. For sixteen writers, today is a wonderful day, but it really has no bearing on the status of any Canadian writer who is not among them on the Giller list.

PS: If I ruled the world (which would be a dictatorship, certainly), first books would be ineligible for book prizes…

September 5, 2011

QUARC

Throughout August, I had the joy of making my way through QUARC, a joint venture between The New Quarterly and ARC Poetry Magazine. The two estimable mags had decided to put their covers together, just once, and to play on the theme their combined names suggested. And so the issue was devoted to the place where art meets science, writers exploring this most unparticular point in an extraordinary variety of ways.

Throughout August, I had the joy of making my way through QUARC, a joint venture between The New Quarterly and ARC Poetry Magazine. The two estimable mags had decided to put their covers together, just once, and to play on the theme their combined names suggested. And so the issue was devoted to the place where art meets science, writers exploring this most unparticular point in an extraordinary variety of ways.

The whole package is absolutely stunning, with each side of the magazine featuring its own gorgeous colour spread, and so much bang for your buck– it’s the size of a small city phonebook. I started with the ARC side, with Margaret Atwood’s “Annie the Ant”, which she’d written in childhood (and I think this is where EO Wilson got the idea for his novel…), and then a short essay on the story and what we can detect of Atwood’s current preoccupations in her younger self. And then a wonderful selection of poems all about animals (this section has been entitled “Bestiary”), accompanied by illustrations of scientific specimens.

I loved Patricia Young’s poems about the various disturbing ways that animals have sex. There is an excerpt from Joan Thomas’ novel Curiosity, about a real life 19th century fossil hunter (who happened to be female), and then an interview with Thomas, with this wonderful passage: “Maybe we’d think more holistically if we’d retained the terms “natural history” or “natural philosophy” for what we now call “science”. There is a narrative in evolution so huge that it boggles the mind. The deeper we go, the more we find to marvel at…”

Then a series of poems by Danielle Devereaux about and/or starring Rachel Carson. The full colour spread is a series of photos  devoted to the narrative of obsolescence, which is more complex that we imagine– a circuit board from a 1960s computer, a dictaphone from the 1930s, and a cosmic ray machine. A PK Page glosa, Christian Bok as “language as virus”, a fascinating essay by Aradhana Choudhuri called “Code as Poetry”.

devoted to the narrative of obsolescence, which is more complex that we imagine– a circuit board from a 1960s computer, a dictaphone from the 1930s, and a cosmic ray machine. A PK Page glosa, Christian Bok as “language as virus”, a fascinating essay by Aradhana Choudhuri called “Code as Poetry”.

The New Quarterly asked its writers for “particle fictions”, creative responses to the rather fanciful names of quarks: Charm, Strange, Up, Down, Top and Bottom (or Truth and Beauty). Following these selections is an interview with Alice Munro by TNQ and ARC editors about her short story “Too Much Happiness”, about the mathematician Sophia Kovalevsky. I loved Robyn Sarah’s “The Scientist as Philosopher”, Alice Major’s mind-twisting “The Ultraviolent Catastrophe”, Don McKay’s “The Holy Ground of Plate Tectonics”, Susan Ioannou’s “Rocks and Words”– all right, I’m just quoting the table of contents now, but you get my point.

And then the exquisite “Ova Aves”, which is a full-colour excerpt from the letterpress book composed of photographs of eggs from the Mount Allison University biology collection, and accompanying poems by Harry Thurston: “Osprey”, “Common Loon”, and (intriguingly), “Unknown”, then an interview with Mount A. ornithologist Gay Hansen, curator of the collection, who answers a question I’d never considered: “What is an egg?”. The issue ends with three poems by Zachariah Wells, which I adored, in particular “The Engineer Produces Intelligent Design”. On eyes: “Shortsighted, longsighted, astigmatic/ crosseyed, walleyed, colour blind, macular/ degeneration, glaucoma, cataracts– that the sucker’s ever work’s miraculous.”

Truth be told, there was lot in these pages that I didn’t understand, but even truthier be told is that this is my experience often when I encounter a literary journal. And yet there was something marvelous about the concreteness of the ideas that still baffled me, and beauty in unpoetic language as rendered poetic.

QUARC is a wondrous object to behold, and I’d urge you to pick up a copy while you still can.

September 5, 2011

A is for Art

Alphabetically speaking, we’ve had a very successful weekend. Though this picture is sort of cheating. We didn’t actually go to the Art Gallery, but rather walked by it on our walk home from the wonderful Textile Museum of Canada. The Magic Squares exhibit was cool in particular as I’d just finished reading The Quarc Issue, which was about the intersections between art and science. The exhibit was about the intersections between mathematics and art in West African clothing, the mathematical and spiritual significance of many of the patterns. Then after that, we went downstairs to play with looms, do some knitting, and molest various kinds of fibres. Finally, we explored the excellent Museum Shop where we did most of our Christmas shopping…

September 5, 2011

X is for the Ex!

We went to the CNE today, and had a wonderful time. Highlights were the LM Montgomery Society booth, the flower/vegetable show (in particularly the prize-winning celery), tiny donuts, deep-fried oreos, colouring at the AGO booth, the farm building where we saw cows, horses, ostriches, alpacas, pigs, chickens, sheep and goats, plus the butter sculptures. And the amazing sand sculptures! Also the rednecks– unbelievable– they must bus these people in. And the food building– we had a healthy dinner of pierogies and poutine, just to keep everything deep-fried consistent. And the best part is that we got to go home on the streetcar…

September 1, 2011

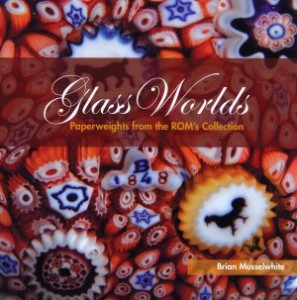

Glass Worlds

The ROM gift shop is one of my favourite local bookstores, and I covet several volumes from their collection. And it was to my great joy that last weekend I acquired a prized one, Glass Worlds: Paperweights from the ROM’s Collection by Brian Musselwhite (who has the best name ever). The book is a catalogue from the ROM’s 2007 paperweight exhibition, much of which is still on show, actually, tucked away in the northeast corner of the building on the 3rd floor– I suspect I am its most frequent visitor. I find the paperweights absolutely beautiful, and I’m fascinated by the juxtaposition of the dullness of their utility with their absolute unnecessary-ness at the same time. As well as their extravagance.

The ROM gift shop is one of my favourite local bookstores, and I covet several volumes from their collection. And it was to my great joy that last weekend I acquired a prized one, Glass Worlds: Paperweights from the ROM’s Collection by Brian Musselwhite (who has the best name ever). The book is a catalogue from the ROM’s 2007 paperweight exhibition, much of which is still on show, actually, tucked away in the northeast corner of the building on the 3rd floor– I suspect I am its most frequent visitor. I find the paperweights absolutely beautiful, and I’m fascinated by the juxtaposition of the dullness of their utility with their absolute unnecessary-ness at the same time. As well as their extravagance.

Musselwhite notes that their popularity grew with growth of literacy, and the popularity of letter-writing. Before most homes were outfitted with electricity, desks would be placed near windows for the best light, but with windows come breezes, hence the paperweight. Though Musselwhite points out that many other objects could have served its purpose: “Most likely, as the Victorians spent so much time at their desks, they wanted to look at something beautiful.”

August 31, 2011

Natural Order by Brian Francis

Whereas Brian Francis’ novel Fruit (which should have won and nearly did win Canada Reads 2009) was a hilarious little story with an undercurrent of sadness, his second book Natural Order is a sad huge story with an undercurrent of hilarity. Fruit ended with Peter Paddington on the cusp of his teenage years, his dawning awareness of his homosexuality, of a darkness on the horizon. The darkness was so subtle you might have missed it in this deceivingly light novel, and it is this darkness that Francis tackles in this latest book.

Whereas Brian Francis’ novel Fruit (which should have won and nearly did win Canada Reads 2009) was a hilarious little story with an undercurrent of sadness, his second book Natural Order is a sad huge story with an undercurrent of hilarity. Fruit ended with Peter Paddington on the cusp of his teenage years, his dawning awareness of his homosexuality, of a darkness on the horizon. The darkness was so subtle you might have missed it in this deceivingly light novel, and it is this darkness that Francis tackles in this latest book.

The book begins with a death notice from 1984, John Sparks dead of a sudden illness at the age of 31. He is survived by his parents, aunts and uncles, and cousins. And then in the first chapter, we meet his mother Joyce years later, living out the final years of her life in an old age home. Her husband has died, she had no other family, and hers is a lonely life that has caused her to grow a brittle shell. Her one diversion is visits from a volunteer called Timothy, a young man who is gay, and though she at first resists his attempts at connection, she warms to him because he reminds her of her son.

Times run together for the elderly, blurred borders between yesterday and today, and so accordingly, Joyce’s narrative reaches out in a variety of directions. In her youth, she’d developed a crush on a flamboyant co-worker who later commits suicide; we meet Joyce as a young mother delighting in her son; years later, she is dealing with the distance of a son whose true life she refuses to acknowledge (which makes his death, from AIDS, all the more painful. Not that she learns from this– she tells everyone he’s died of cancer). A major componant of the plot involves Joyce as a widow, still living in her home but becoming aware that her days there are numbered, and a discovery she makes that forces her to acknowledge her shortcomings as a mother and a wife.

The delights of this novel are many– Francis writes with a steady hand, creating believable characters who talk and act like people do. I particularly loved Joyce’s friends and neighbours– her single friend Fern in the red sequinned shirt, and her neighbour Mr. Sparrow who calls her to warm her about a strange man prowling around her house, who he’s since invited in for a coffee. Also, jokes about United Church Women who can whip up “a salmon loaf standing on [their] head[s] in thirty seconds”. Though my favourite joke is when Joyce goes over to visit a friend whose father had years before fallen off the roof during a lightning storm: “Stay off the roof,” my father said.

At times, Joyce seems too aware of her role in the story (“But the only way I could control things was if John went to the college here and stayed at home”), but for the most part, Francis has done a stunning job of getting into this character’s mind and creating sympathy for her. He shows Joyce’s overbearing nature as the result of a mother’s efforts to protect a boy who always had a hard time fitting in and faced persecution at school, and her refusal to acknowledge just how exactly he was different as a product of her time and culture.

I’m not crazy about the cover of this book– the whole point of Joyce is her unworldliness, and that she spent her whole life quite sure that the world in her backyard was the world as it was, and what I mean is that she never took her son to the seaside. But her stubbornness in clinging to her own view in the world is what makes her such a compelling narrator. At the end of a life of deception, she becomes quite adept at unflinching truths. She is wry, funny, and far more observant of others’ true nature than perhaps she ever wanted to be.

Brian Francis’ prose is wonderfully readable, he has a talent for perfect detail, though perhaps the novel’s greatest strength lies in how the many different story-lines and time-lines are woven together seamlessly. His generosity with happy endings is measured out just enough to be believable, but also for the novel to be uplifting, and Joyce Sparks is certainly a worthy addition to the canon of Hagar Shipley, Georgia Danforth Whitely, Daisy Stone Goodwill etc.: “I am not at peace.”

August 30, 2011

Here be (no) dragons

One day, after ages of it being beloved, Harriet suddenly refused to let me read Sheree Fitch’s Sleeping Dragons All Around. At that point, she was unable to articulate why, but it was still significant as the first time a book had been outright rejected (as opposed to, say, abandoned out of boredom, which is different).

One day, after ages of it being beloved, Harriet suddenly refused to let me read Sheree Fitch’s Sleeping Dragons All Around. At that point, she was unable to articulate why, but it was still significant as the first time a book had been outright rejected (as opposed to, say, abandoned out of boredom, which is different).

She also wouldn’t let us read her The Lady With the Alligator Purse— we’re still not sure why. But by the time she’d gone off two books as various as Neil Gaiman’s Instructions and Robert Munsch’s The Paper Bag Princess, I’d started detecting a theme. And by this time, Harriet had the words to explain: “Too scary,” she told us. Apparently it’s a fire-breathing dragon thing.

But how did she discover that dragons were scary? I’d certainly gone out of my way never to mention such a thing. In fact, I’d never mentioned that there was such a thing as “scary” at all, because little people are so open to suggestion, and I’ve been working hard on cultivating fearlessness. I don’t really do “scary” anyway, except when it comes to sensible things like diving off cliffs and tightrope walking. The closest thing I’ve got to an irrational fear is an extreme unease around dogs (which is not so irrational, I’d argue, because they’re equipped with teeth that could chew your face off), but I promise you that around a dog, Harriet has never, ever seen me flinch.

So this dragons thing has brought me to the limits of my powers, my powers of “cultivation”, and I get it that this is only the beginning of a very long education. And I get it too that it doesn’t take a genius to deduce that oversized fire-breathing lizards are probably best left undistubed between covers. (Interestingly, Harriet’s dragon aversion doesn’t extend to dinosaurs. She loves dinosaurs–plush, fossilized, wooden, Edwina, you name it.)

The thing is actually, that I fucking hate books with dragons (some excellent picture books aside). It’s true. I always have– when I was growing up, I never read a single book with a dragon on the cover. Which wasn’t really difficult to accomplish, because there weren’t many books with dragons on the cover. (My YA self would have been horrified by the popularity of science-fiction/fantasy today. And my adult self remains mystified.) A dragon on the cover was a kind of book design shorthand for “boring book for nerds”, and though I was certainly a nerd, I was the type of nerd who preferred books about pretty girls dying of anorexia or getting cancer.

Fantasy books: here’s another place where I’ve come to the limits of my own powers. I just can’t get into them, though I’ve tried. And I think back and wonder if I’d been less dragon-phobic in my youth, maybe fantasy-appreciation would come easier to me. There are a lot of things I wish I’d spent most of my life being a lot more open minded about, hence the reason why I want to make Harriet’s literary horizons broad from the very start. I want her to read better than I did, but then she persists in having her own feelings about things. She persists in refusing to be malleable, in having fears and preferences and in being a person apart from me.

But also a person who is very much like me, which I’m not sure is more or less disconcerting.