February 16, 2012

"It was not that I merely read The New Yorker; I lived it in a private way"

“It was not that I merely read The New Yorker; I lived it in a private way. I had created for myself a New Yorker world (located somewhere east of Westport and west of the Cotswolds) where Peter de Vries (punning softly) was forever lifting a glass of Piesporter, where Niccolo Tucci (in a plum velvet dinner jacket) flirted in Italian with Muriel Spark, where Nabokov sipped tawny port from a prismatic goblet (while a Red Admirable perched on his pinky), and where John Updike tripped over the master’s Swiss shoes, excusing himself charmingly (repeating all the while that Nabokov was the best writer of English currently holding American citizenship). Meanwhile, the Indian writers clustered in a corner punjabbering away in Sellerian accents (and giving off a pervasive odor of curry) and the Irish memorists (in fishermen’s sweaters and whiskey breath) were busy snubbing the prissily tweedy English memorists.

Oh, I had mythicized other magazines and literary quarterlies, too, but The New Yorker had been my shrine since childhood. (Commentary, for example, held rather grubby gatherings at which bilious-looking Semites-all of whom were named Irving-worried each other to death about Jewishness, Blackness, and Consciousness, while dipping into bowls of chopped liver and platters of Nova Scotia.) These soirees amused me, but it was for The New Yorker that I reserved my awe. I never would have dared to send my own puny efforts there, so it outraged and amazed me to find someone I had actually known frequenting its pages.” –Erica Jong, Fear of Flying

February 14, 2012

The Winter Palace by Eva Stachniak

Historical fiction is one of my groundless literary prejudices, so I must admit that Eva Stachniak’s The Winter Palace was not an immediate draw. But then I got to know Eva a bit and she’s lovely, plus her book’s reception has been so overwhelmingly positive, and having conquered Wolf Hall, I’m not afraid of anything anymore. So I decided to go for it, and I loved it.

Historical fiction is one of my groundless literary prejudices, so I must admit that Eva Stachniak’s The Winter Palace was not an immediate draw. But then I got to know Eva a bit and she’s lovely, plus her book’s reception has been so overwhelmingly positive, and having conquered Wolf Hall, I’m not afraid of anything anymore. So I decided to go for it, and I loved it.

That I would love it seemed a sure thing from the top of page 12 when I encountered the line, “My father was a bookbinder.” Another of my literary prejudices is that if you stick a bookbinder if your novel, I will adore it, and in particular if the narrative goes into the intricacies of bookbinding, the book as object, has characters who are readers, and has pivotal scenes taking place in libraries, imperial or otherwise. Everybody is reading in this novel– narrator Barbara’s young daughter leafs through old books looking for pictures of herself, Stachniak so perfectly articulating how children read to see their selves reflected. Her recently-crowned Catherine the Great takes care to keep her afternoons clear so she can read alone in her room (though imperial business threatens to interfere with this arrangement). Barbara herself achieves status in the imperial palace after a chance run-in with the Russian Chancellor in the library, gaining a new position reading aloud to the Crown Prince.

We see the 18th century Russian court through the eyes of Barbara, a Polish immigrant and orphan who is in Princess Elizabeth’s debt because her late- father the bookbinder had once repaired a tattered, treasured prayer book. Barbara is defined by her mutability, even down to her name: “Barbara, or Basienka, my mother called me. In Polish, as in Russian, a name has many transformations. It can expand or contract, sound official and hard or soft and playful. Its shifting shape can turn its bearer into a helpless child or a woman in charge. A lover or a lady, a friend or a foe./ In Russian, I became Varvana.”

Varvana begins working as a seamstress in the Winter Palace, a position for which she is horribly unsuited, but she has other skills, and these are noticed. She is enlisted by the Chancellor to become a “tongue”, one who reports on palace goings-on. She becomes closer to the Empress Elizabeth, and also to the Grand Duchess Catherine who arrives at the palace to marry the Crown-Prince, and soon it becomes unclear where her loyalties lie (or rather, she begins to develop loyalties where she should have none at all). Her unclear loyalties become evident to Empress Elizabeth as well, who marries Varvana off to a Palace Guard to be rid of her, but this doesn’t manage to sever her connection to Catherine. As Elizabeth gets frailer, the system of power becomes precarious, and Varvana must finally take a side, even if just for the purposes of self-preservation. But it’s more than that– she has come to care for and trust the Grand Duchess Catherine, who’s on the verge of becoming Catherine the Great. But is anyone really worthy of trust in the Winter Palace, where loyalties are as fluid as identities are? What will be the consequences of ceasing to be just a pair of eyes and ears, and attempting to live without fear as a real human being?

The historical details through the eyes of Barbara are made accessible and vivid, the latter point by the exquisiteness of Stachniak’s prose. (I kept highlighting passages I especially loved, like the part about the expanding names. I think my favourite line was, “Hope can be as brittle as a wishbone”.) The characters are made human, in particular by their presence in their bodies, which miscarry, get diseases and become disfigured over time. There are no stock characters here, which is saying something a book with so many characters, but Stachniak manages the right strokes to bring her people to life with a remarkably human complexity (in particular, Barbara’s husband, and how I admired the connection that grows up between them). The plot is riveting and makes every page-turn in this 400+ page book seem most worthwhile, and I loved the ending, how the narrator steps away from the tale of Catherine the Great, and we manage to see what we’ve always suspected: that Barbara has been the hero of her story all along.

February 12, 2012

Wild Libraries I Have Known: Quiet Reading Room at the Amundsen Scott South Pole Station

How exciting that the Wild Libraries series hits its 5th continent with this post by Laura Conchelos, perhaps our wildest post yet (or at least most extreme). I met Laura nearly twenty years ago, and ever after, she’s been one of my most fascinating friends. I enjoy her adventures vicariously, and delight in the Christmas cards to the South Pole that our friendship gives me occasion to send.

How exciting that the Wild Libraries series hits its 5th continent with this post by Laura Conchelos, perhaps our wildest post yet (or at least most extreme). I met Laura nearly twenty years ago, and ever after, she’s been one of my most fascinating friends. I enjoy her adventures vicariously, and delight in the Christmas cards to the South Pole that our friendship gives me occasion to send.

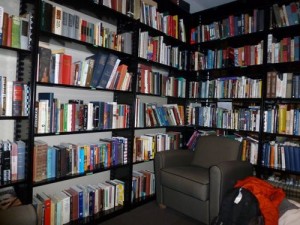

It may not look like much but the Quiet Reading Room at the Amundsen Scott South Pole Station is pretty important to us. We work for the United States Antarctic Program which runs and supports science at the South Pole with the National Science Foundation. Unlike many libraries these days, it’s strictly books and magazines here with some audio books and CDs thrown in for good measure. For our computer needs, we use our own laptops in our rooms or go to the computer room.

It may not look like much but the Quiet Reading Room at the Amundsen Scott South Pole Station is pretty important to us. We work for the United States Antarctic Program which runs and supports science at the South Pole with the National Science Foundation. Unlike many libraries these days, it’s strictly books and magazines here with some audio books and CDs thrown in for good measure. For our computer needs, we use our own laptops in our rooms or go to the computer room.

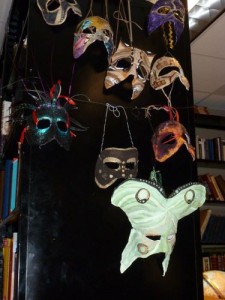

This room isn’t as cute or cozy as many libraries but it is chock full of good reading for  those with the patience to look. Most recent bestsellers can be found here, left by someone else and available for the taking. I usually end up with a stack of books from this room next to my bed that I have to return at the end of our four-month season. Usually I haven’t read half of them! By the end of the 8-month South Pole winter, the Reading Room looks grand, as somebody often has taken it under his or her wing and put energy into reorganizing and labeling the books. Most of the books are novels but there are history books, short stories, poetry, travel, religion and education sections, amongst others. Just as the books get donated over the years, the reading room has been decorated with odds and ends over time, my favorite items being the masks that were made for our wearable art show a few years ago and which can be seen here.

those with the patience to look. Most recent bestsellers can be found here, left by someone else and available for the taking. I usually end up with a stack of books from this room next to my bed that I have to return at the end of our four-month season. Usually I haven’t read half of them! By the end of the 8-month South Pole winter, the Reading Room looks grand, as somebody often has taken it under his or her wing and put energy into reorganizing and labeling the books. Most of the books are novels but there are history books, short stories, poetry, travel, religion and education sections, amongst others. Just as the books get donated over the years, the reading room has been decorated with odds and ends over time, my favorite items being the masks that were made for our wearable art show a few years ago and which can be seen here.

A locked cabinet in the room keeps most of the Antarctic-themed books and other coveted reading. Most of the knitting books get kept in the cabinet, as do the travel guides like the Lonely Planet. All one needs to do to sign these books out is get the keys from the store during its daily hours of operation.

A locked cabinet in the room keeps most of the Antarctic-themed books and other coveted reading. Most of the knitting books get kept in the cabinet, as do the travel guides like the Lonely Planet. All one needs to do to sign these books out is get the keys from the store during its daily hours of operation.

Apart from pilfering for good reading or doing crossword puzzles here on Sundays  (our one day off), I spend little time in this room. It does get a lot of use from others, however. As the station is such a public place, there are not many locations within it that offer some sort of quiet. People go here to read, write letters, and nap when they don’t want to make the long trek to their rooms. This room is also used by visiting clergy for Masses and church services.

(our one day off), I spend little time in this room. It does get a lot of use from others, however. As the station is such a public place, there are not many locations within it that offer some sort of quiet. People go here to read, write letters, and nap when they don’t want to make the long trek to their rooms. This room is also used by visiting clergy for Masses and church services.

February 10, 2012

Our Best Book of the Library Haul: Our House by Emma and Paul Rogers, Priscilla Lamont

I love picture books that show the passage of time, the largeness of history and our relative smallness (but our place nonetheless) in the scheme. And of course, I also love house books, so Emma and Paul Rogers’ Our House, which is illustrated by Priscilla Lamont, was inevitably going to be a delight. The illustrations are very Ahlberg-meets-Shirley Hughes, and the sense of place and history in the text is similar to Virginia Lee Burton’s in The Little House and Life Story. The book is made up of four pretty ordinary domestic stories taking place in 1780, 1840, 1910, and 1990, each showing subtle changes in the house and surrounding area, and also the lifestyles of its changing inhabitants. The final story shows an awareness of the people who’d lived in the house before, as the family, whilst searching for an errant pet mouse, finds bits of history under floorboards and in backs of cupboards. (“We shed as we pick up, like travellers who must carry everything in their arms, and what we let fall will be picked up by those left behind.”– Tom Stoppard, Arcadia.) There is no supernatural element at work here, but the connection between the child in the first story and the child at the end reminded me of my favourite time out of time novels like Tom’s Midnight Garden, Charlotte Sometimes, and A Handful of Time. And of course, we love the pictures where the house’s fourth wall has come away and we can see its skeleton, under its floorboard, plumbing, all the rooms and the people who make their lives inside them.

I love picture books that show the passage of time, the largeness of history and our relative smallness (but our place nonetheless) in the scheme. And of course, I also love house books, so Emma and Paul Rogers’ Our House, which is illustrated by Priscilla Lamont, was inevitably going to be a delight. The illustrations are very Ahlberg-meets-Shirley Hughes, and the sense of place and history in the text is similar to Virginia Lee Burton’s in The Little House and Life Story. The book is made up of four pretty ordinary domestic stories taking place in 1780, 1840, 1910, and 1990, each showing subtle changes in the house and surrounding area, and also the lifestyles of its changing inhabitants. The final story shows an awareness of the people who’d lived in the house before, as the family, whilst searching for an errant pet mouse, finds bits of history under floorboards and in backs of cupboards. (“We shed as we pick up, like travellers who must carry everything in their arms, and what we let fall will be picked up by those left behind.”– Tom Stoppard, Arcadia.) There is no supernatural element at work here, but the connection between the child in the first story and the child at the end reminded me of my favourite time out of time novels like Tom’s Midnight Garden, Charlotte Sometimes, and A Handful of Time. And of course, we love the pictures where the house’s fourth wall has come away and we can see its skeleton, under its floorboard, plumbing, all the rooms and the people who make their lives inside them.

Bonus: Our best short film of the library haul appeared on the very excellent Harry the Dirty Dog DVD by Scholastic, and is the excellent “I Want a Dog” by Sheldon Cohen. Based on the book by Dayal Kaur Khalsa, narrated by Marnie McPhail (who was Annie Edison!!), and with a soundtrack by Neko Case, it’s absolutely wonderful AND you can watch it on the National Film Board of Canada website!

February 9, 2012

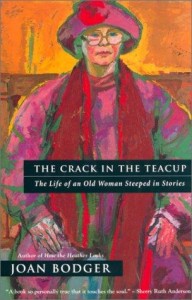

Of Myths and Mad Men: Rereading Joan Bodger's The Crack in the Teacup

It was only two years ago that I first read Joan Bodger’s The Crack in the Teacup, but revisiting it was an experience that was altogether new. First, because my interest in children’s literature has become so much deeper since then (mostly due to what I learned from reading this book the first time, and from Bodger’s other book How the Heather Looks) and also because of Mad Men. But we’ll get to that.

It was only two years ago that I first read Joan Bodger’s The Crack in the Teacup, but revisiting it was an experience that was altogether new. First, because my interest in children’s literature has become so much deeper since then (mostly due to what I learned from reading this book the first time, and from Bodger’s other book How the Heather Looks) and also because of Mad Men. But we’ll get to that.

I do think that A Crack in the Teacup might be one of my favourite books ever. I read it over five days last week, and absolutely would not shut up about it. You will see. The beginning is a little slow, if only because Bodger’s childhood is spent at a remove from the rest of the world. Which is what makes it interesting of course, but she examines it in such minute detail, perhaps because these details of a happy time are so much more pleasant to examine than what comes later.

I think it is inevitable that one becomes a storyteller when one can write about her grandfather’s first wife who was killed in a shipwreck in 1877. Really, all the ingredients here are the stuff of storybooks: her mother is English, the daughter of a sailor whose third wife is a quarter Chinese, who grows up in a stately home surrounded by books but no schooling, spends her teenage years crippled after being flung from a horse, and then recovers enough to drive an ambulance during WW1 (without a license). She marries an American at the end of the War, moves across the sea, and has three daughters (with Bodger in the middle). Her husband joins the US coast guard chasing rum runners and leading ships out of Arctic ice after failed polar expeditions, and they spend the ’20s and ’30s moving up and down east and west coasts.

It was a happy enough childhood, rich with stories and lore, but also an isolated one. Bodger’s immigrant mother held herself apart from American society, and that the family moved around so much didn’t help matters. From early on, Bodger had a hard time fitting in, accepting authority, understanding how the world worked outside the Higbee family. There was also so much that was never talked about– her mother’s health problems, father’s infidelities, her own burgeoning sexuality, her yearning for the education her father didn’t feel was necessary for a daughter to have. Bodger and her sisters were being groomed to be ladies, roles none of them would easily fulfil.

Bodger’s college plans are diverted by WW2, she joins the army, and becomes a bumbling decoder (“I put my hand in the grab bag and pulled out a message about a place spelled Yalta. Obviously a mistake! I changed the Y to M.”) She goes back to school once the war is finished, and meets John Bodger, a graduate student and fellow veteran. She’s head over heels, and without a doubt that their life together will be a happy one as he completes his PhD (with her love and support, of course), and becomes internationally recognized as the brilliant mind he obviously is.

Which is where Mad Men comes into play. Apart from a few years in California, the Bodgers spend the ’50s and early ’60s living in and around Westchester County NY, which is Cheever-country, the world of Mad Men. And though the Bodgers could not pretend to be the cookie cutter figures their suburban surroundings suggested, it”s the same backdrop, healthy kids and big green lawns, the war in the past now, educated mothers idle in the afternoons, philandering husbands, cracks becoming apparent in all kinds of veneers. It soon becomes apparent that not all is right with John Bodger: he struggles to hold down a job at all, has to give up his academic aspirations, begins to display signs of paranoia. Joan Bodger makes life-long connections with the women in her neighbourhood, many of whom have similary troubled marriages and dissatisfaction with their lives. But she doesn’t connect with all her neighbours:

“Bette told me that another woman in the neighbourhood was writing a book– a sort of update to Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. Her name was Betty Friedan. She lived just down the street from us; her little girl was in Lucy’s class. I telephoned her. I felt silly doing it, yet I longed to talk shop with someone. How do you manage to write with kids around? Betty Friedan said she was too busy to talk to every suburban housewife who called her.”

The book Bodger was writing, of course, was How the Heather Looks, the story of a trip her family takes to England in 1958 to rediscover worlds they only knew from storybooks, to make end paper maps come alive. A book whose portrayal of ideal family life belies the real story of her family– John Bodger would be diagnosed with schizophrenia, he and Joan would eventually divorce. Before their divorce, their daughter Lucy would die of a brain tumour, and their son Ian would battle his own demons, with mental illness and drug addiction. And throughout these tragedies, it is Bodger’s faith in story that enables her to survive. And not neat stories either, with beginnings, middle and ends, but rather the dark archetypal stories with no end that occur over and over in cultures all around the world, and which give our own experiences depth and meaning, that help us to understand the things that happen to us in our lives.

But story, of course, is useful in a more practical sense as well. Eager for diversions after Lucy’s death, Bodger becomes involved in an education program to promote graduation rates for black students in her town of Nyack NY. She realizes that although she lives in the very same town, she knows nothing about the lives of the black people around her. She starts sitting on the steps of a church in the black neighbourhood, armed with candy and picture books to give away (because by this time, she’s become a children’s book reviewer, and has plenty of review copies to spare), ready to make some connections. She quickly discerns that the picture books she’s brought are useless– they reflect nothing of the lives of the children she’s trying to reach, and many of the children don’t know how to relate to or connect with a book anyway. So she starts telling stories instead, and she’s good at it. Eventually a police man contacts her and says he’s concerned she’s going to stop telling stories when the weather gets cold. He’s with the NAACP and they want to help her out– could they get her an indoor place where the children can go to hear her?

Bodger uses what she learns from this experience to set up a free nursery school in the neighbourhood, and continues to learn about what children’s literature can do. She writes about the impact of black children seeing somebody like themselves in storybooks for the first time in Ezra Jack Keats’ A Snowy Day, and about her own conversations with Keats about resisting their liberal impulses and acknowledging the childrens’ race. (“Not until we gave ourselves permission to see their blackness could these children give themselves permission to see themselves.”) Similarly about the powers of books like Where the Wild Things Are and A Apple Pie to encourage children to express their own feelings of rage, anger and aggression. To begin to tell stories themselves, to make the stories their own.

Her husband and son drift far away from her as she becomes more involved in early literacy and storytelling. Eventually Bodger leaves New York and for short time works for the library association of Missouri (where her ability to make waves is less accepted than it had been in New York, and she is eventually dismissed from her job, somewhat farfetchedly, for being “a communist pornographer” [and her second husband would jokingly complain of the false advertising of that title]). She head back east and works in editing and consulting for Random House, though still shell-shocked and heartbroken by the tragedy she’d had to weather: “Just a few years before, I had had a husband, two children, a house on the Hudson River. Wave a magic wand and I’m spending half my life in a one-room apartment in Greenwich Village, complete with cockroaches in the fridge and drug addicts on the stairs.”

On a business trip to Detroit, she sidelines to Toronto to visit the famous Osborne Collection of Children’s Literature. On June 18, 1970 (which was, I should note, thirty-five years to the day before I got married), she was standing under an awning waiting out a sun-shower when a man came up behind her and commented on her reading, which was Stuart Little. He wondered why she was marking up the pages with proofreaders marks, which he recognized because he worked in publishing too. “‘Anyone who would change one jot or title of EB White’s prose, I could have nothing to do with,’ he said.” The man was Alan Mercer, a writer and photographer, and the love of Bodger’s life. Within two weeks, they knew they would be getting married, Bodger resettling to Toronto and the two of them establishing a marriage of much support and love, but also independence. Mercer died in 1985 of cancer, and though the loss would ever be a scar she bore, she would never be as broken as she’d been before she found him. She tells him, “When I met you, I felt as though I were walking around with a gaping wound. You healed me.”

The rest of the book narrates Bodger’s involvement with establishing the Storytellers School of Toronto, and also some of her travels. I found the end of the book less compelling than the middle, though I’m not sure it could have been any other way. And it’s fitting really– Rick Salutin is wrong and so is Diane Sawyer. Stories aren’t about endings at all, but about how they weave our experiences into the tapestry of human existence, and the strands twist and turn in incredible ways, and no connection is without meaning– so that it is significant that Bodger meets her husband on my wedding anniversary, how she connects the narrative of her own life to folk tales, about how her experiences are microcosmic of the mid-20th century with civil rights and the women’s movement. (I suppose it’s also significant that Ian Bodger was convicted of blowing up a police car last month to protest state healthcare cuts. There are no happy endings indeed.)

Another thing that has changed in my life since I read this book in April 2010 is that at least once a week I visit the Lillian H. Smith Library now, where the Osborne Collection is now located and where Bodger scattered her husband’s ashes after his death. (He’d wanted them scattered in the foundation for the opera house at Bay and Wellesley, which they’d be able to see from their apartment balcony on Church Street, but the opera house was never built. When the Lillian H. Smith Library was under construction, Bodger deemed the site a bit too far west, but otherwise perfect.) I finished reading The Crack in the Teacup last Sunday evening, and was under a Bodger-spell when we went to the library the following morning. We got there a few minutes early and went upstairs to the Obsborne Centre before the toddler program started. I wanted to see the lectern where the guestbook is kept, a guestbook I’ve even signed and seen so many times, but whose significance I’d never noted until I read this book again. Inscribed on a plaque upon it: “Alan Nelson Mercer, 1920-1985. He loved a good sentence.”

As Bodger writes of this library that is such an important part of my family life, investing this place with infinite meaning (and this is the stuff of story, don’t you think?):

“…I was finally allowed, after months of committee meetings, to present a Hepplewhite-style lectern where the guestbook would repose. The committee, of course, was kept ignorant of my grander plan: to make the airy, playful, much-used library building into a fitting mausoleum for a man who loved cities, loved book, and words, loved me.”

February 7, 2012

The Betrayal of Trust by Susan Hill

While the business of writing, publishing and book selling in Canada has certainly been adversely affected by the economic chaos of the past four years, our stories themselves have largely remained untouched by such things. (Possible exceptions are a few writers working with post-apocalyptic visions, but I would bet their work is more prescient than written in response to current events.) Elsewhere, however, in countries where effects of crises have been more overt, the literature is already reflecting economic troubles and their impacts– the Irish real-estate boom was an overarching theme of Anne Enright’s brilliant The Forgotten Waltz, and Penelope Lively’s How It All Began has banks going bust and bottoms falling out of businesses built on too much credit.

While the business of writing, publishing and book selling in Canada has certainly been adversely affected by the economic chaos of the past four years, our stories themselves have largely remained untouched by such things. (Possible exceptions are a few writers working with post-apocalyptic visions, but I would bet their work is more prescient than written in response to current events.) Elsewhere, however, in countries where effects of crises have been more overt, the literature is already reflecting economic troubles and their impacts– the Irish real-estate boom was an overarching theme of Anne Enright’s brilliant The Forgotten Waltz, and Penelope Lively’s How It All Began has banks going bust and bottoms falling out of businesses built on too much credit.

And even detective fiction isn’t safe. Susan Hill’s latest Simon Serrailler novel The Betrayal of Trust is operating in a very current environment of austerity and cuts. When flash floods unearth the bodies of two dead women in Lafferton, Simon is without the resources necessary to assemble a team to investigate their murders thoroughly. One of the bodies is that of a local teenage girl who’d gone missing fifteen years ago, but the identity of the other remains unknown, and it’s a mystery what happened to either of them. Simon must find a way to crack these cold cases, even venturing to try a crime show re-enactment on television to do the job the police themselves would have done not so long ago. Even after all these years, he knows that someone out there must know something.

Susan Hill is one of those writers I mentioned when I read Louise Penny in December, part of a British tradition of mystery writers who can really write. She’s written five other books in the Simon Serrailler series (I read The Vows of Silence in 2008), numerous works of literary fiction, she’s the author of The Woman in Black (which has just been made into a film starring Harry Potter, no less!), and I adored her Howards End is On the Landing. She’s got cred, and it shows through in The Betrayal of Trust, whose characters are rich and whole and woven into several plots that offer the novel its depth– Simon is lovelorn, we meet his recently widowed sister Cat who is a doctor working with hospice patients (and yes, the hospice too is struggling to find funding). One of her patients has just received a terminal diagnosis, and is considering the decision to end her own life. Another character, whose connection to the plot we’re not quite sure of until the end, is struggling to care for a partner whose dementia has rendered her a violent stranger. Hill herself has never been shy with her politics, which means that euthanasia here is treated for the most part without nuance and as a sinister business undermining the sanctity of life from all angles, and also that Serrailler and his murder investigation is not this novel’s chief focus. The second point, however, I don’t intend as a criticism; the crime novels that are most rich have as much life as they have murder (even if here, the life is mostly concerned with its end).

The two Simon Serrailler novels I’ve read have featured meta glimpses of the real world within its page, The Vows of Silence with its dedications to “The Wedding Guests” (!). In The Betrayal of Trust, Hill acknowledges a debt to Antonia Fraser, which became apparent to me on page 117 when Simon at the end of a party faces the (married) woman he’s met that night and asks her, “Must you go?” I cheered in recognition, and so began another narrative strand of the novel, Simon in love. And while this strand, with others, is not so neatly tied up by the book’s end, the open-endedness of Hill’s conclusion makes particularly clear that we’ll have another Simon Serrailler novel to look forward to before long.

February 6, 2012

Me and Teddy Jam at Green Gables

Kristen den Hartog’s Blog of Green Gables is one of the most fascinating, thoughtful, inspiring blogs I’ve ever encountered, and so I’m absolutely honoured to have a guest post appear there today. My post “Once there was a baby…” is the story of how Teddy Jam’s Night Cars became the story of our family, which is really part of a deeper story about the way that the worlds of picture books become a part of our own.

Kristen den Hartog’s Blog of Green Gables is one of the most fascinating, thoughtful, inspiring blogs I’ve ever encountered, and so I’m absolutely honoured to have a guest post appear there today. My post “Once there was a baby…” is the story of how Teddy Jam’s Night Cars became the story of our family, which is really part of a deeper story about the way that the worlds of picture books become a part of our own.

“But the baby arrived, and Night Cars became our story too. Whose rhythm is really a lullaby, an almost-nonsense verse whose meaning became clearer the less sleep I got: “Someone needs a pillow/ Call a taxi on the phone/ Someone needs a good-night kiss/ Someone’s eyes have fallen down.” Read the rest!

February 5, 2012

Our Saturday Morning Book Crawl

On Friday, I read about the opening of Sellers & Newal, a new bookstore on College Street, and then hatched a plan for a Saturday morning book crawl. In order to make a “Saturday morning book crawl” attractive to my husband, I mapped out a route that involved stopping at Sam James Coffee Bar, and breakfast at the Lakeview. It was a sunny, gorgeous morning and felt just like springtime. The walk down to Dundas and Ossington was particularly lovely because we hadn’t seen the sun in ages.

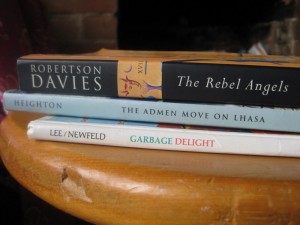

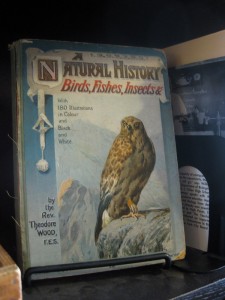

After breakfast, we walked west on Dundas to The Monkey’s Paw, where I’d never been before but had heard so much about. It’s a bookstore of secondhand curiosities, and if we hadn’t had a monster child in tow (with a case of the “nearly-threes”), we could have browsed for ages. Highlights included vintage cookery books, a wall of Penguins, Toronto-health pamphlets on

After breakfast, we walked west on Dundas to The Monkey’s Paw, where I’d never been before but had heard so much about. It’s a bookstore of secondhand curiosities, and if we hadn’t had a monster child in tow (with a case of the “nearly-threes”), we could have browsed for ages. Highlights included vintage cookery books, a wall of Penguins, Toronto-health pamphlets on  baby-rearing from the ’40s, a book by Shari Lewis on making puppets and several old typewriters whose Hs Harriet wanted to press. Old atlases, books about UFOs, goatherding and sex. The air was marvelously redolent with dustiness and books— “something smells funny in here,” was how Harriet so charmingly put it as soon as we walked in the door. I ended up getting a copy of Dennis Lee’s Garbage Delight, which I’d never read before but it turns out to be the best of all wonderful his picture book. (My favourite poem inside is “Worm”.)

baby-rearing from the ’40s, a book by Shari Lewis on making puppets and several old typewriters whose Hs Harriet wanted to press. Old atlases, books about UFOs, goatherding and sex. The air was marvelously redolent with dustiness and books— “something smells funny in here,” was how Harriet so charmingly put it as soon as we walked in the door. I ended up getting a copy of Dennis Lee’s Garbage Delight, which I’d never read before but it turns out to be the best of all wonderful his picture book. (My favourite poem inside is “Worm”.)

Then we went to the new store, Sellers & Newal, and I browsed while Harriet (who had decided she wouldn’t wear shoes) was held captive in her stroller, and read to from Garbage Delight by her father. So many cool books here, and not much dust because the store is brand new (as well as bright and airy). Lots of good Canadian fiction, books on advertising, typography and graphic design, a set of Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books, affordable paperbacks, collectable hardcovers, and a shelf that was built out of a coffin. Oh my! I was happy to get a copy of Steven Heighton’s essay collection The Admen Move on Lhasa.

Then we went to the new store, Sellers & Newal, and I browsed while Harriet (who had decided she wouldn’t wear shoes) was held captive in her stroller, and read to from Garbage Delight by her father. So many cool books here, and not much dust because the store is brand new (as well as bright and airy). Lots of good Canadian fiction, books on advertising, typography and graphic design, a set of Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books, affordable paperbacks, collectable hardcovers, and a shelf that was built out of a coffin. Oh my! I was happy to get a copy of Steven Heighton’s essay collection The Admen Move on Lhasa.

And then finally to Balfour Books at their excellent dust-free, light-filled location near College and Bathurst. Which is where my family won the Patience Prize as they sat up at the front near the door (you can see them in the picture) and not once asked me if I was done yet. And because they were so considerate, I did my best to be done as yet as possible. I finally got my hands on a copy of Robertson Davies’ The Rebel Angels, which my friend Patricia has recommended, because she says that those of us who only read Fifth Business in high school don’t know Robertson Davies at all.

And by then it was nearly naptime, so to home. Harriet was wished good dreams, and I curled up on the couch and read and read and read (and knit).

February 2, 2012

The New Quarterly 120: Love is Abroad

I’m behind on the times because The New Quarterly 121 has just shown up in my mailbox (which was very crowded. Apparently my downstairs neighbour has just taken out a subscription to The New Quarterly). But I still want to write about how fabulous the last issue was.

I’m behind on the times because The New Quarterly 121 has just shown up in my mailbox (which was very crowded. Apparently my downstairs neighbour has just taken out a subscription to The New Quarterly). But I still want to write about how fabulous the last issue was.

It featured the winner of the Edna Staebler Personal Essay Contest, Lisa Martin-DeMoor, whose poetry I reviewed nearly two years ago. Her essay “A Container of Light” did that brilliant thing that great essays do, which is to take something very personal personal and intimate, and shine a light upon that story in such a way that the story becomes one about something much bigger. It is particularly significant that Martin-DeMoor is writing about a miscarriage, about mourning and loss, because how do you tell a story bigger that that? But she does, and it’s beautiful: “How light is always leaping out of darkness, even when a light goes out.”

Catriona Wright’s essay “You Just Put Your Lips Together and Blow” resonated with me for personal reasons– I find the sound of whistling more grating than any other on earth. Wright addresses her own compulsive whistling (and the negative reviews it has received), and also the history and meaning of of whistling cross-culturally: “In Hawaii it is supposed to bring bad luck because it mimics the language of the Nightmarchers, ghosts of ancient Hawaiian warriors.” Totally! Also instances of whistling in pop songs, the wolf-whistle and Emmet Till, and the few remaining professional whistlers out there.

Stephen Heighton’s short story “Dialogues of Departure” was wonderful, the story of a Canadian English teacher in Japan who begins to learn Japanese through a language textbook with sinister undertones. (And it got me thinking about books stories about Canadian/Japanese experience– Heighton’s collection Flights Path of the Emperor, Catherine Hanrahan’s Lost Girls and Love Hotels, Sarah Sheard’s Almost Japanese, and even my short story “Georgia Coffee Star”.) Mark Anthony Jarman’s “Adam & Eve Saved from Drowning” was so incredibly good, Jarman’s mastery of language creating an effect that was as rich and sad as it was funny.

I also enjoyed Sara Heinonen’s “Blue Dress”, the story of a woman as lost in her life as she is in Hong Kong (and it was nice to read Heinonen’s fiction, as I enjoy her blog very much). And then “The Fires of Soweto” by Heather Davidson, and we’re told, “This is her first published story”, and I will tell you that this is what small magazines are for. What an amazing discovery. I suspect we’ll be hearing more from her.

And then if that weren’t enough, they publish two poems by one of my most beloved poets, Kerry Ryan. And another by Susan Telfer, who wrote one of my favourite books of 2010.

Every time I receive The New Quarterly, I have this weird sense that it’s been custom-edited just for my pleasure. It’s one of the great pleasures of my life to be a subscriber.