April 29, 2012

Morstad, Nadeau and Arsenault: 3 Great Illustrators

I realize that I’m not telling you anything you don’t know already, because it’s not that these illustrators are up-and-coming, but that they’re everywhere. Behind the books we love and books we’re still discovering, and perhaps it’s incidental that all the books they illustrate are brilliant, but I suspect it isn’t. In fact, I think that at least half of the brilliance these illustrators can totally take credit for.

Julie Morstad: I first bought a child one of Julie Morstad’s Henry books (written by Sara O’Leary) back in 2008, and have been doing so regularly ever since, as recently as last weekend. (It was When I Was Small. Went over a charm). She’s also the pictorial force behind the award-winning Singing Away the Dark by Caroline Woodward, which I adore, and also the art book Milk Teeth by Drawn & Quarterly, which I’m currently winding my little head around. And now I hear she’s got a new book, an illustrated version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s poem The Swing and I am so very excited.

Julie Morstad: I first bought a child one of Julie Morstad’s Henry books (written by Sara O’Leary) back in 2008, and have been doing so regularly ever since, as recently as last weekend. (It was When I Was Small. Went over a charm). She’s also the pictorial force behind the award-winning Singing Away the Dark by Caroline Woodward, which I adore, and also the art book Milk Teeth by Drawn & Quarterly, which I’m currently winding my little head around. And now I hear she’s got a new book, an illustrated version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s poem The Swing and I am so very excited.

Janice Nadeau: Nadeau is the illustrator of Cinnamon Baby, which is one of our family’s favourite books ever (and I gave a copy of this book to somebody as recently as yesterday). Like Morstad and Arsenault, her illustrations have a vintage feel, an irresistible prettiness, but are also a bit cheeky and whimsical. She is also the illustrator of the award-winning graphic novel Harvey, and she’s the creator of the poster for 2012 TD Children’s Book Week (which is currently hanging on Harriet’s bedroom door).

Isabelle Arsenault: We discovered Isabelle Arsenault via Kyo Maclear’s wonderful first picture book Spork: never has cutlery appeared so full of vitality (and so shiny!). Harriet was still little but found the illustrations, of the baby in particular, very appealing. And then along came Arsenault next with Maxine Trottier’s award-winning Migrant, the beautiful story of a little girl from Mexico whose family comes north to Canada to work as farmers every summer. Her latest is Virginia Wolf, also with Maclear, and I’ve already written about how much I adore it. Though I haven’t bought a copy yet for any library except our own, but I suspect it’s going to make a good gift one of these days soon.

Isabelle Arsenault: We discovered Isabelle Arsenault via Kyo Maclear’s wonderful first picture book Spork: never has cutlery appeared so full of vitality (and so shiny!). Harriet was still little but found the illustrations, of the baby in particular, very appealing. And then along came Arsenault next with Maxine Trottier’s award-winning Migrant, the beautiful story of a little girl from Mexico whose family comes north to Canada to work as farmers every summer. Her latest is Virginia Wolf, also with Maclear, and I’ve already written about how much I adore it. Though I haven’t bought a copy yet for any library except our own, but I suspect it’s going to make a good gift one of these days soon.

April 26, 2012

On Girls Fall Down: "Like it's liminal between real and imaginary, you know?"

As it was when I first read this book in 2008, the plot is weak, but then plot is not the point in Maggie Helwig’s Girls Fall Down, which is this year’s One Book Toronto read and also one of the most evocative Toronto books I’ve read ever. And it’s been a funny week on my end, nothing dire, much that’s lovely, but just very busy and divorced from the strict routine my life is constructed around usually. Yesterday, I rode the subway so many times I bought a day-pass, and it was a strange thing to be reading this book on the TTC and carrying it through other places where some its most important scenes are set. It was a strange thing also to come home from a gathering where emotions were particularly heightened, and I kept thinking about the line on page 128, “our lives marked always by the proximity of others.”

As it was when I first read this book in 2008, the plot is weak, but then plot is not the point in Maggie Helwig’s Girls Fall Down, which is this year’s One Book Toronto read and also one of the most evocative Toronto books I’ve read ever. And it’s been a funny week on my end, nothing dire, much that’s lovely, but just very busy and divorced from the strict routine my life is constructed around usually. Yesterday, I rode the subway so many times I bought a day-pass, and it was a strange thing to be reading this book on the TTC and carrying it through other places where some its most important scenes are set. It was a strange thing also to come home from a gathering where emotions were particularly heightened, and I kept thinking about the line on page 128, “our lives marked always by the proximity of others.”

It’s such an atmospheric book, and the atmosphere keeps stealing into my own. Today I felt like Alex does: “…everything now seemed to assimilate into the city’s larger narrative.” Or rather, the city assimilating into Maggie Helwig’s narrative. It’s remarkable, isn’t it, the curious places where fact and fiction meet. Today I encounter the newspaper headline, “Students, staff at Scarborough elementary school fall ill”. ““They did a thorough inspection of the school and carbon monoxide or any other airborne problems were deemed not to be the cause,” said… spokesman for the Toronto Catholic District School Board”. And even the abortion clinic scenes, and today’s attack on Canadian women’s reproductive rights.

“So it was like that now, catastrophe inevitable at the most empty moments. Everyone waiting, almost wanting it, a secret, guilty desire for meaning. Their time in history made significant for once by that distant wall of black cloud.”

And it’s funny because my reaction to this book upon first read was that the Toronto under siege depicted felt so foreign to me– I’d missed the SARS epidemic, and the big black-out. But Helwig’s city feels more familiar now, and not just the police brutality since this happened, or how much awful the world is in 2012 as compared to how it was in 2008 (which is much). More amusingly, there’s the scene where the pigeon gets into the hospital, which definitely means more since this happened (and the birds! How I have to reread Headhunter).

But I think basically I’ve just been overwrought this last day or so and that the weather has been funny, but still. What crazy things fiction can do to our minds, and the innumerable ways our stories appear to affect the world.

April 26, 2012

Funny women

“This is what I used to think about Sherry– wait, that’s not what I meant to say. I never really thought anything about Sherry. Except that she always seemed like a nice person. I don’t know if I would’ve said before this that she was nice enough to give you the shirt off her back, but when you stop and think about it, that’s a lot to ask from someone.” –Jessica Westhead, “We Are All About Wendy Now”

“This is what I used to think about Sherry– wait, that’s not what I meant to say. I never really thought anything about Sherry. Except that she always seemed like a nice person. I don’t know if I would’ve said before this that she was nice enough to give you the shirt off her back, but when you stop and think about it, that’s a lot to ask from someone.” –Jessica Westhead, “We Are All About Wendy Now”

This is from page 3 of Jessica’s collection And Also Sharks. And now is the time when I think we need to start an award for women’s humour writing, because I don’t think the establishment gets it. Also Caroline Adderson, Zsuzsi Gartner (the exchange student riding the tortoise!!!), Heather Birrell (“Geraldine and Jerome”, anyone? So funny: ‘”It’s okay,” said Geradline. “I like your belt.”‘), Anne Perdue, Julie Booker, Anakana Schofield, Esme Claire Keith, Laura Boudreau, Lynn Coady, Suzette Mayr, Carolyn Black (Martin Amis! Remember Martin Amis?).

We could fill a fucking ballroom.

The humour is so dark and subtle though, with all of these women. Perhaps this is what the Leacockians aren’t getting (and when is the last time you laughed out loud at Sunshine Sketches, laughed so hard that you woke up your husband and then insisted on reading him entire paragraphs? Seriously?).

In these books are suicides, paraplegics, decapitations, dead babies, and maimed pot-bellied pigs. And they’re so funny they’ll make your heart hurt. Which is way funnier than heart-hurt caused by systemic discrimination and disregard of brilliant women writers, no?

Ha ha ha.

UPDATE: In all fairness, I see that the list of entries for this year’s Leacock Prize did not include many of last year’s funniest books. Though if I were them, I’d still want to revamp my program to get a broader range of books to choose from.

April 25, 2012

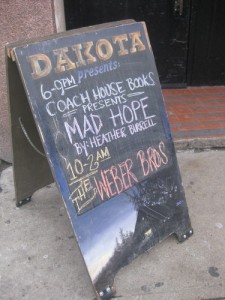

Mad Hope is launched

My friends-writing-extraordinary-books streak continues with Heather Birrell‘s story collection Mad Hope, which is so rich and wonderful. We’re currently working together on an interview that I’m looking forward to sharing with you soon. But in the meantime, I wanted to share photos from Heather’s launch last night at the Dakota Tavern. Her reading was brilliant, followed by an excellent interview with Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer. The room was packed with Heather fans, and it was really a most enjoyable evening. PS You can still get a copy of her story Frogs for free.

My friends-writing-extraordinary-books streak continues with Heather Birrell‘s story collection Mad Hope, which is so rich and wonderful. We’re currently working together on an interview that I’m looking forward to sharing with you soon. But in the meantime, I wanted to share photos from Heather’s launch last night at the Dakota Tavern. Her reading was brilliant, followed by an excellent interview with Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer. The room was packed with Heather fans, and it was really a most enjoyable evening. PS You can still get a copy of her story Frogs for free.

April 24, 2012

What We Talk About When We Talk About War by Noah Richler

Noah Richler’s new book What We Talk About When We Talk About War comes with a warning label of a blurb with Margaret MacMillan’s “You don’t have to agree with everything Noah Richler says — I don’t — but you must take him seriously.” Which is is the first sign that we’re dealing with a polemic that exists to complicate the idea of polemicism. (It is also helpful a helpful blurb if you’re part of the choir Richler is preaching to– to keep an open mind is the very point.) The second sign that we’re dealing with such a polemic is Richler’s explanation of his book’s title, which comes from the Raymond Carver story whose full sentence is, “It ought to make us feel ashamed when we talk like we know what we’re talking about when we’re talking about love.” And so it should with war, according to Richler, in particular for those who’ve been in charge of our “strategy” in Afghanistan since 2001 and so clearly didn’t.

Noah Richler’s new book What We Talk About When We Talk About War comes with a warning label of a blurb with Margaret MacMillan’s “You don’t have to agree with everything Noah Richler says — I don’t — but you must take him seriously.” Which is is the first sign that we’re dealing with a polemic that exists to complicate the idea of polemicism. (It is also helpful a helpful blurb if you’re part of the choir Richler is preaching to– to keep an open mind is the very point.) The second sign that we’re dealing with such a polemic is Richler’s explanation of his book’s title, which comes from the Raymond Carver story whose full sentence is, “It ought to make us feel ashamed when we talk like we know what we’re talking about when we’re talking about love.” And so it should with war, according to Richler, in particular for those who’ve been in charge of our “strategy” in Afghanistan since 2001 and so clearly didn’t.

Most of my impressions of war were formed from the perspectives of my grandfathers who served in the Canadian Navy during World War Two and never had anything to say about war other than that it was awful. There was also the letters long saved that my father’s father had written home to his wife and children during the many years he had to spend away from them. And a story about the body of a dead German, my grandfather’s long lasting impression that inside that man’s wallet there would have been photos of a family much like his own. Which is not to say that my grandfathers did not take pride in their years of service– I spent many a Remembrance Day watching my grandfather march in parade, his medals displayed. I’ve spent more time than you would imagine at the old Naval Club on Hayden Street. But I mostly remember listening to the lists of the ships that were lost in the fighting. I remember being told over and over that the reason they had fought was so that war could be obliterated. Back when I was learning what I know about war, they kept telling us, “Never again.”

Peacekeeping was invented by men who’d learned too much about war, and forgotten by men who’d never known it at all. In the years since my days at the Naval Club, Remembrance Day has been hijacked, the story of “peacekeeping” has been denigrated, and our country has been at war for a decade. And Richler shows that none of this just came about, but was instead the result of a deliberate campaign to shift public thinking, and build up the Canadian military in order to underline the presence of Canada on the international stage. At heart, the shift was rhetorical– we understand ourselves and our lives in terms of stories, and that story has moved in the last ten years from the complex shape of the novel with humanity at its core, to the simplistic epic tale with easy-to-grasp binaries of good and evil.

Richler outlines the circuity of the rhetorical arrangements– the government, think-tanks, the Canadian military has been successful at militarizing the Canadian mind-set by keeping Canadians so at a remove from war itself (which has not been difficult– Afghanistan is far away). That the media has been complicit in the game because war is news, it makes reporters feel useful and excited. That the liberal hippy-dippy platitudes of peacekeeping and love your brother are as empty as the troop-supporting sentiments expressed by ardent war-mongers like Don Cherry or Christie Blatchford (“The time we take to pay dues to war’s brutality… is an ersatz moral act that excuses actually having to do anything more proactive about a subject that is innately horrific.”) That the Afghanistan mission (which only turned into a “mission” once the war itself had become a little bit stale) became less about “war-making” and more about peacekeeping (and school building!) as the conflict wore on, the very approach that “top soldiers” had resisted in the beginning. That the military and government were able to turn instances of public mourning into public relations opportunities. Richler writes, “Ritual works, brilliantly. What chance does dissidence have when monolithic acclamation is the order of the day?”

Our notions of heroics have been hollowed out to exalt those in uniform to extents that are absurd. Women are exempt from this narrative unless they’re requiring rescue, Richler comparing responses to the deaths of photojournalist Tim Hetherington and Calgary Herald reporter Michelle Lang. Our language has been obfuscated, imbued with euphemism– torture is “enhanced interrogation,” a mission is war. The tragic disaster that was the Battle of Vimy Ridge is now a story of glory. People who dare to complicate the dictum of “Support Our Troops” are met with hateful vitriol.

“This is what passes for think-tank work in Canada, which is remarkable but what we have to put up with until others speak up,” writes Richler of a somewhat blathering blog post in which Canadian historian Jack Granatstein once again attempts to lay to rest the myth of the Canadian peacekeeper. In his book, Richler shows how these others have been silenced by rhetoric, and speaks up himself with an erudite text packed with wide-ranging references from Greek myth to modern video games, resisting all accusations of loftiness with a his very constructive final chapter, “What is to be Done?” (and there is plenty).

And while Richler’s message would have been better conveyed in particular to those beyond his choir with a bit more clarity and conciseness (as well as further editing. This text is a mess, though is promised to be cleaned up by next printing), it will be a relief to those of us who feel the same that someone is speaking up finally.

April 22, 2012

The Famous 5

So many things I love are a part of this photo. Also, we had a really wonderful trip to Ottawa this weekend. Lots of reading on the train, hotel fun, good food, friends, and, speaking of friends, we were the beneficiaries of some amazing hospitality. Long live the Mini-Break!

So many things I love are a part of this photo. Also, we had a really wonderful trip to Ottawa this weekend. Lots of reading on the train, hotel fun, good food, friends, and, speaking of friends, we were the beneficiaries of some amazing hospitality. Long live the Mini-Break!

April 18, 2012

Mini Review: Brief Lives by Anita Brookner

“There is no charm to Anita Brookner”, I wrote last year when I read her novel Look At Me. Like Barbara Pym with just the lonely bits. The book was slow and depressing, and while I appreciated what was good about it, I didn’t like it. I probably would never have picked up an Anita Brookner novel again except that I found this one in a cardboard box on the curb in January. We had a ridiculously mild winter this year, a cardboard box of free books on the curb in January was an even surer sign than lack of snow that something was askew climatologically speaking. But it was the only such box I’d seen in months so I picked through it, took this one home and I read it over the last couple of days.

“There is no charm to Anita Brookner”, I wrote last year when I read her novel Look At Me. Like Barbara Pym with just the lonely bits. The book was slow and depressing, and while I appreciated what was good about it, I didn’t like it. I probably would never have picked up an Anita Brookner novel again except that I found this one in a cardboard box on the curb in January. We had a ridiculously mild winter this year, a cardboard box of free books on the curb in January was an even surer sign than lack of snow that something was askew climatologically speaking. But it was the only such box I’d seen in months so I picked through it, took this one home and I read it over the last couple of days.

And that I read it over a couple of days suggests that pace-wise it was better-going than my last Brookner. Though it features the same kind of self-effacing narrator whose unreliability is never affirmed, only subtly suggested (and how does she do that subtlety? The narrator who ever so subtly is not really so subtle). With all tell and very little show, Brookner tells the story of Fay Langdon, a singer who gives up her career when she marries Owen whose business brings her into contact with the magnificent and obnoxious Julia. Fay asserts continually that she and Julia have little in common beyond their husbands’ relationship, that each exists on the other’s periphery, but the careful reader will discern otherwise.Who is the true victim here, and who is the villainess? What are the limits to Fay’s extraordinary self-denial?

Still not much in the way of charm, even better this was really good. A compelling and enjoyable read.

April 18, 2012

Don't pick the flowers

“Don’t pick the flowers” is a cardinal rule at our house (along with “Don’t chase the pigeons”). It is so important to me that Harriet learn to engage with and appreciate nature without torturing or destroying it. Not every experience needs to be hands-on. And so what she’s come to understand about the flowers we encounter in our neighbourhood (and gloriously, there are so so many) is that they’re still growing. When she touches them, she has to be gentle. “They’re still growing?” she asks me, looking back over her shoulder, and when I nod, she seems to get it. But we’ve made an exception for the dandelions. Not because they’re lesser flowers, but because they’re a flower of abundance. She seems to get this too. And so we gathered a bouquet on Monday morning on our way home from the library, and it’s been decades since I did this. It’s been decades since I sat at a table with a dandelion centrepiece. I’d forgotten there had even been such centrepieces, but there were so many, and as we picked our flowers, it all came back to me. The “this was why I had a child” moment I didn’t even know that I was waiting for. And the lesson too about exceptions– as important as the lesson about still growing. How important it is for our children to grasp that we live in a bendy and beautiful world.

“Don’t pick the flowers” is a cardinal rule at our house (along with “Don’t chase the pigeons”). It is so important to me that Harriet learn to engage with and appreciate nature without torturing or destroying it. Not every experience needs to be hands-on. And so what she’s come to understand about the flowers we encounter in our neighbourhood (and gloriously, there are so so many) is that they’re still growing. When she touches them, she has to be gentle. “They’re still growing?” she asks me, looking back over her shoulder, and when I nod, she seems to get it. But we’ve made an exception for the dandelions. Not because they’re lesser flowers, but because they’re a flower of abundance. She seems to get this too. And so we gathered a bouquet on Monday morning on our way home from the library, and it’s been decades since I did this. It’s been decades since I sat at a table with a dandelion centrepiece. I’d forgotten there had even been such centrepieces, but there were so many, and as we picked our flowers, it all came back to me. The “this was why I had a child” moment I didn’t even know that I was waiting for. And the lesson too about exceptions– as important as the lesson about still growing. How important it is for our children to grasp that we live in a bendy and beautiful world.

April 16, 2012

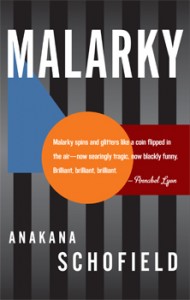

Malarky by Anakana Schofield

If Hagar Shipley met Stella Gibbons, the end result might be Anakana Schofield’s Malarky, but then again, it probably wouldn’t be, because Malarky refuses to be what you think it is. And moreover, it probably wouldn’t be because the book is meant to be chock-a-block with allusions to James Joyce and Thomas Hardy. Don’t tell anybody, but I still haven’t read Ulysses (and hence the Gibbons instead of the primary sources), but I have read Malarky, and it was brilliant, which I know for certain even with the burden of my literary ignorance. And that I can pronounce a book as wonderful even whilst unable to access its higher planes of greatness is certainly saying something for the book itself, which is mostly, “You’ll like it too.”

If Hagar Shipley met Stella Gibbons, the end result might be Anakana Schofield’s Malarky, but then again, it probably wouldn’t be, because Malarky refuses to be what you think it is. And moreover, it probably wouldn’t be because the book is meant to be chock-a-block with allusions to James Joyce and Thomas Hardy. Don’t tell anybody, but I still haven’t read Ulysses (and hence the Gibbons instead of the primary sources), but I have read Malarky, and it was brilliant, which I know for certain even with the burden of my literary ignorance. And that I can pronounce a book as wonderful even whilst unable to access its higher planes of greatness is certainly saying something for the book itself, which is mostly, “You’ll like it too.”

Schofield’s heroine, Our Woman, if she can be summed up at all, will be summed up with the explanation she gives for the period of despair she suffered after the birth of her first child: “Then I had a cup of tea and six weeks later, I felt better.” There is so much that goes unspoken of, silences to be filled with the rudiments of life as a farming wife, of motherhood, of friendship with her gang of local women (“…not a day passed when several of them didn’t meet. They were like tight ligaments in each other’s life, contracting, extending and sustaining the muscle of each other, house to house, tongue to ear”).

The bottom falls out, however, when she discovers her son up to unmentionable things with the neighbour’s boy. Our Woman’s stress is compounded by a woman she meets in town who confesses to her that she’s been doing unmentionable things with Our Woman’s husband. In response, Our Woman goes out into the world determined to do a few unmentionable things of her own to learn a thing or two, but the situation becomes more complicated– her son takes off to join the US army and local rumour has it that he did it to get away from her, and also her obsession with what she saw him doing becomes a kind of fascination, a desire to be close to him in an impossible way that suggests local rumours could be true.

But it’s hard to tell. Malarky is very much of the world– the Irish economy, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the plight of immigrants, mental illness, grief– and yet, its interiority is impermeable. When Our Woman spies her son shirtless in the barn, she notes, “He must have been freezing, his pale body bleary and quivering, trousers at his ankles.” However perversely, she is ever a mother, urging on a sweater. But she’s not just a comic figure; Schofield evokes Our Women with remarkable sympathy: “Mainly she had wanted to hit him about the head and shout these aren’t the things I have planned for you.” Malarky is a journey beyond the limits of love, an equally sad and hilarious portrait of motherhood.

“Malarky is like nothing else, and what everything should be,” is something I wrote down this weekend. First, because it’s as funny as it’s dark, and also because it dares readers to be brave enough to follow along an unconventional narrative. Though the winding path is only deceptively tricky– Our Woman’s voice is instantly familiar, and the shifting perspectives remain so intimate and immediate that the reader follows. Consenting to be led, of course, which is the magic of Malarky. This is a book that will leave you demanding more of everything else you read.

April 15, 2012

Only in hindsight

I loved Stephen Marche’s piece “The Persistence of Mad Men”: “Everything in Mad Men is predictable, but only in hindsight.” Marita Dachsel and Carrie Snyder, two women I like and admire, have a conversation about The Juliet Stories, motherhood, and the writing life. Carrie Snyder also turns up at Blog of Green Gables writing about the various stages of reading with her children. I love that Sarah Tsaing is writer-in-residence at Open Book Toronto this month. Sarah is also on the New Generation of Canadian Poets, which has its own page at Amazon. Jonathan Bennett on Kyo Maclear’s Stray Love. Nathalie Foy likes Jo Walton’s Among Others. My friend Erin gave me a Cath Kidson Diamond Jubilee mug (which should go really well with my new bunting, which is due to arrive in the post soon. And how amazing that I get to spend the next couple of weeks anticipating bunting in the post [because is there any greater state of being?]). Blogs that are interesting me lately and challenging notions of the form: Habicurious (“Exploring the intersection of people, their housing and communities”), and Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer’s May I Stare At You?, and Heinonen on writing and reading fiction (in particular, lately, “The Notebook Habit and the Hell of Notebooks“). Richard Florida on “Why Young Americans Are Driving So Much Less Than Their Parents”. And finally, we’re currently building a box city at our house (of cereal boxes, pasta boxes and very much lately of tissue boxes) as inspired by Alfred Holden’s Beaver, whose exhibition Stuart and I went to see years ago.

I loved Stephen Marche’s piece “The Persistence of Mad Men”: “Everything in Mad Men is predictable, but only in hindsight.” Marita Dachsel and Carrie Snyder, two women I like and admire, have a conversation about The Juliet Stories, motherhood, and the writing life. Carrie Snyder also turns up at Blog of Green Gables writing about the various stages of reading with her children. I love that Sarah Tsaing is writer-in-residence at Open Book Toronto this month. Sarah is also on the New Generation of Canadian Poets, which has its own page at Amazon. Jonathan Bennett on Kyo Maclear’s Stray Love. Nathalie Foy likes Jo Walton’s Among Others. My friend Erin gave me a Cath Kidson Diamond Jubilee mug (which should go really well with my new bunting, which is due to arrive in the post soon. And how amazing that I get to spend the next couple of weeks anticipating bunting in the post [because is there any greater state of being?]). Blogs that are interesting me lately and challenging notions of the form: Habicurious (“Exploring the intersection of people, their housing and communities”), and Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer’s May I Stare At You?, and Heinonen on writing and reading fiction (in particular, lately, “The Notebook Habit and the Hell of Notebooks“). Richard Florida on “Why Young Americans Are Driving So Much Less Than Their Parents”. And finally, we’re currently building a box city at our house (of cereal boxes, pasta boxes and very much lately of tissue boxes) as inspired by Alfred Holden’s Beaver, whose exhibition Stuart and I went to see years ago.