May 31, 2012

Full Frontal T.O. by Patrick Cummins and Shawn Micallef

Now here is a book that our entire family can love, though not immediately, because after I picked it up at the bookstore last Thursday evening, I read it all through dinner and didn’t talk to anybody. Which was kind of annoying, but when I finally shared the book, they understood. Even the three year old, who found the pictures fascinating and absorbing, context not really being the point of their appeal. Full Frontal T.O.: Exploring Toronto’s Architectural Vernacular collects a series of photos by Patrick Cummins who’s been documenting Toronto’s street-scapes since the 1980s. Context is provided by way of Shawn Micallef’s pithy text. The photos show how the same city blocks have changed over time in some ways, and remained the same in others– the gist of the approach is shown on the Full Frontal blog.

Now here is a book that our entire family can love, though not immediately, because after I picked it up at the bookstore last Thursday evening, I read it all through dinner and didn’t talk to anybody. Which was kind of annoying, but when I finally shared the book, they understood. Even the three year old, who found the pictures fascinating and absorbing, context not really being the point of their appeal. Full Frontal T.O.: Exploring Toronto’s Architectural Vernacular collects a series of photos by Patrick Cummins who’s been documenting Toronto’s street-scapes since the 1980s. Context is provided by way of Shawn Micallef’s pithy text. The photos show how the same city blocks have changed over time in some ways, and remained the same in others– the gist of the approach is shown on the Full Frontal blog.

The black and white images of single building or blocks changing over time is an urban time machine, showing patterns of decay and gentrification, or stagnation, in other cases. Interspersed throughout the book are full colour spreads of buildings grouped by theme– dead stores, semi-detached houses, gothic cottages, DIY cottages (which is my favourite– these buildings fascinate me), variety stores. And the effect of all of this is make me realize how little I actually see of the city around me. We walk its streets as if we’re sleeping, and then turn to a book like this to find so much that is familiar, so much that is in my neighbourhood, so many buildings that I’ve wondered about (like this one!) but it never occurred me to take curiosity further than that.

Every time I’ve opened this book, I’ve discovered something new– my ex-boyfriend’s old house, places right around the corner, blocks of streets I used to walk down daily, and lines like, “It’s good to stick your head out of a window sometimes because, apart from looking out of, that’s what they’re made for,” a critique of Toronto’s ubiquitous three-panelled windows. And in this way Full Frontal T.O. is a simulacrum of the city itself– you never encounter it the same way twice.

May 29, 2012

The Occasion is Lavender

I only bake when it’s a special occasion, but the problem is that I seem to unearth occasions daily. Today it’s that the lavender in the front garden is in glorious bloom. We snipped twelve sprigs, and then I set to bake lavender cupcakes, which I’ve always wanted to bake, so that’s another life goal accomplished. I used the recipe from Nigella Lawson’s How to Be a Domestic Goddess, which has proven a very poor instruction manual in my experience. All the measurements are in imperial and I don’t own a kitchen scale, so I have to guess the measurements and so I’ve never had a recipe from that book come out right. Though these lavender cupcakes turned out to be pretty damn acceptable. The flower is absolutely delicious. And though Harriet claims that she doesn’t like them, we’ll try her again tomorrow.

I only bake when it’s a special occasion, but the problem is that I seem to unearth occasions daily. Today it’s that the lavender in the front garden is in glorious bloom. We snipped twelve sprigs, and then I set to bake lavender cupcakes, which I’ve always wanted to bake, so that’s another life goal accomplished. I used the recipe from Nigella Lawson’s How to Be a Domestic Goddess, which has proven a very poor instruction manual in my experience. All the measurements are in imperial and I don’t own a kitchen scale, so I have to guess the measurements and so I’ve never had a recipe from that book come out right. Though these lavender cupcakes turned out to be pretty damn acceptable. The flower is absolutely delicious. And though Harriet claims that she doesn’t like them, we’ll try her again tomorrow.

May 28, 2012

All the Voices Cry by Alice Petersen

Summer is here, at least in spirit, and the cover of Alice Petersen’s short story collection All the Voices Cry meant that I had to read the book at once. (Book has been reviewed well already, and been long listed for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award.) Though these are not stories of lazy, hazy days; the fish ain’t jumping and the cotton’s not high. Petersen’s are most often stories of summer places out of season, or of people out of place in those summer places. And the places themselves– rural Quebec, Petersen’s native New Zealand, even Tahiti– frame characters’ expectations in terms of idyll, pastoral, and usually (as is the way) experience comes up short.

Summer is here, at least in spirit, and the cover of Alice Petersen’s short story collection All the Voices Cry meant that I had to read the book at once. (Book has been reviewed well already, and been long listed for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award.) Though these are not stories of lazy, hazy days; the fish ain’t jumping and the cotton’s not high. Petersen’s are most often stories of summer places out of season, or of people out of place in those summer places. And the places themselves– rural Quebec, Petersen’s native New Zealand, even Tahiti– frame characters’ expectations in terms of idyll, pastoral, and usually (as is the way) experience comes up short.

Alice Petersen knows her way around a good sentence: “We knew he drank at night on the boathouse steps; the more beer he drank, the more bottles there were to get a refund on.” This from the first story, whose title “After Summer” is a good way to frame the whole book. A young man is looking back at summer memories and the darker shadows behind them, contemplating his single father’s loneliness, and how the notion of family got away from them. In “Among the Trees”, a widow contemplates the life she’d built around her artist husband which manifested in the artists colony they built together on her family’s property. This colony is a centre the collection revolves around, many of its stories loosely linked to its characters and geography. We see the widow and her husband from the outside in “All the Voices Cry”, in which Freya, another widow, a neighbour and a stranger, walks through the surrounding woods in winter and contemplates her “sustaining illusions”.

We meet Freya again in “To Catch a Fish”, avoiding entering her cabin where her new lover is cooking dinner. And fish aren’t jumping indeed, to great consequence, we see, when Freya makes the choice to choose herself and her solitude, the ground she stands on. In “The Frog”, with subtle gestures, a single mother considers what ties her to her life and beyond it, and how people without children move through life like amphibians (which is something to wrap one’s head around, just what exactly Petersen means by this, and the process of engagement steeps the reader further in the story).

The last six stories in the collection are different from the others, removed from the Quebec landscape we’ve been planted in thus far. Also, these stories are more storied, artificial, set-up than the others (which is not a criticism). Though I could get this impression from these stories’ settings’ unreality in my own mind. They take place in New Zealand gardens, on the International Date Line, on Tahitian cliff sides, foggy beaches. A few of them also have a mystical nature, and maybe that’s where the airiness comes from. A man enacts futile attempts to defy a psychic’s predictions, a woman dares to abandon her vexing husband in the middle of a tropical nowhere, a couple attempts to ignore potentially devastating news by going through the motions of sight-seeing, characters’ own lonely histories bubble up inside them.

None of Petersen’s characters is quite where they’re meant to be, where they want to be, and they see themselves in new lights against the unfamiliar contexts. The book is slim, the stories are subtle and quiet, and though their impact is not always immediate, All the Voices Cry is a collection you might want to meditate on, its pages getting dog-earned and stained with coffee rings as the summer wears on.

UPDATE: Speaking of quiet depth…

May 28, 2012

Harriet turns 3

Harriet turned three this weekend, and highlights included a fire station tour as part of Doors Open Toronto, much fun with good food and sunshine, and a fantastic party yesterday with ten friends, their siblings and moms and dads. We had a wonderful time, and the party met with my definition of party success, which was that Harriet didn’t cry. Or at least not until after everyone had left, and she was sad because, “There’s only one kid now. I want my friends!” But during the party itself, she had the most wonderful time, dancing, running, laughing, cupcaking, pinning tails in hilarious manners, and delighting in her wonderful pals. A terrific celebration of a girl who’s just as good. And now we’re all a bit tired…

Harriet turned three this weekend, and highlights included a fire station tour as part of Doors Open Toronto, much fun with good food and sunshine, and a fantastic party yesterday with ten friends, their siblings and moms and dads. We had a wonderful time, and the party met with my definition of party success, which was that Harriet didn’t cry. Or at least not until after everyone had left, and she was sad because, “There’s only one kid now. I want my friends!” But during the party itself, she had the most wonderful time, dancing, running, laughing, cupcaking, pinning tails in hilarious manners, and delighting in her wonderful pals. A terrific celebration of a girl who’s just as good. And now we’re all a bit tired…

May 25, 2012

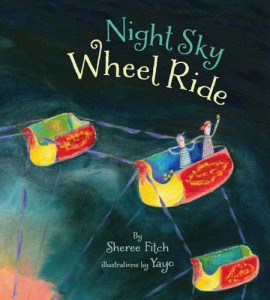

New book by Sheree Fitch: Night Sky Wheel Ride

A new book by Sheree Fitch is a very important event in our house, and so we were overjoyed to get our copy of Night Sky Wheel Ride yesterday. It’s the story of a Ferris wheel ride against a night sky and the dark sea, a brother and sister ecstatic at finally being big enough to ride. “Are we big enough this year, Mama?/ Are we brave enough, Brother?/ Sister, are you ready to fly?” Fitch’s free verse is delicious to recite, full of twists and turns that melt “sticky quick on the tips of our tongues.” Rhymes and repetition replicate the Ferris wheel’s momentum, and apart from the people down below who are “dancing jelly beans”, the poem’s imagery stays pretty literal because when you’re dealing with a Ferris wheel, metaphors aren’t entirely necessary. The illustrations, however, tell an altogether different story, Yayo taking cues from the language and pushing the story even further with a furious whimsy, turning everything into absolutely nothing like it seems. His Ferris wheel is an apple tree, a rowboat, a washing machine’s spin cycle, a bird perch.”Can you hear the mermaids murmur/beluga whales sing/ feel the whirling stir/ of every little humming phosphorescent thing?”

A new book by Sheree Fitch is a very important event in our house, and so we were overjoyed to get our copy of Night Sky Wheel Ride yesterday. It’s the story of a Ferris wheel ride against a night sky and the dark sea, a brother and sister ecstatic at finally being big enough to ride. “Are we big enough this year, Mama?/ Are we brave enough, Brother?/ Sister, are you ready to fly?” Fitch’s free verse is delicious to recite, full of twists and turns that melt “sticky quick on the tips of our tongues.” Rhymes and repetition replicate the Ferris wheel’s momentum, and apart from the people down below who are “dancing jelly beans”, the poem’s imagery stays pretty literal because when you’re dealing with a Ferris wheel, metaphors aren’t entirely necessary. The illustrations, however, tell an altogether different story, Yayo taking cues from the language and pushing the story even further with a furious whimsy, turning everything into absolutely nothing like it seems. His Ferris wheel is an apple tree, a rowboat, a washing machine’s spin cycle, a bird perch.”Can you hear the mermaids murmur/beluga whales sing/ feel the whirling stir/ of every little humming phosphorescent thing?”

The story takes on a special poignancy when you learn the story behind it.

May 23, 2012

On not being part of the problem

I spend a ridiculous amount of time being frustrated at the way women (artists in particular) are misrepresented and unrepresented in the media and in the world. It is not even the lack of appreciation for women’s work that bothers me as much as the perpetual lack of acknowledgement by so many critical voices and outlets that women artists actually exist.

I spend a ridiculous amount of time being frustrated at the way women (artists in particular) are misrepresented and unrepresented in the media and in the world. It is not even the lack of appreciation for women’s work that bothers me as much as the perpetual lack of acknowledgement by so many critical voices and outlets that women artists actually exist.

So accordingly, I find myself particularly attuned to issues of diversity in my own editing work, whether at 49thShelf, or in another editing project I’m undertaking at the moment. (I wonder: is this attunement a womanly thing? Does it take one to know one?). And it’s hard, it really is. The people I know and the people I like tend to be like me, and it’s so easy to look around this bubble I inhabit and forget it’s not the world. It takes a lot of trouble to reach outside my own limits, my own contacts. It also makes me uncomfortable to consider that a writer might think I was approaching him/her for reasons of diversity– this just seems offensive. Though I suppose that if a male editor got in touch with me one day and said, “Hey, I was just looking over my contributors and realized I’d forgotten about women and this is a problem,” I’d be more than happy to help fill the gap. I’d also probably think that the editor was a pretty classy guy.

But not being part of the problem extends past my work as editor. Though I realize that the problems I’m writing about here are very much systemic, I am willing to take some responsibility for having been being part of that system sometimes. For being that woman writer whom editors approach and never hear back from, of being nervous, intimidated, not brave enough to take myself and my work very seriously, to ask for what I deserve. I am willing to take some responsibility for the number of times I haven’t been brave at all.

But for a while, this has been changing. For an even longer while, pretending not to be scared has been my very best counter to fear, but lately genuine fearlessness has been easier to come by. A huge part of this is being a part of an incredible group of women writers, friends and mentors among them who bolster me. It was after one of our gatherings last winter that I got the nerve up to respond to an editor who was giving me an opportunity I wasn’t sure I could measure up to, that I had the confidence to take myself as seriously as this editor obviously did for having approached me in the first place. If things are going to change, these mentorships and support systems are the best chance there is. It also helped to have read Tina Fey’s Bossypants, which sounds inane, I realize, but there’s that line, “I don’t fucking care if you don’t like it”: seriously, my life has been remarkably better since I got it stuck in my head.

Eventually being brave, which is the same thing as taking responsibility– it becomes a kind of habit, a reflex. It’s the thing you’ve got to do to not be part of the problem. And it works, this whole not being walked over thing, in a way that’s kind of remarkable. It’s a delightful combination of not taking any shit and not giving a shit, and maybe it’s something you’ve got to wait until your 30s to learn, or else perhaps I am just a late bloomer, but the world opens up when it happens. And then you’ve got the strength, the power, the articulateness to continue take on the parts of the problem that weren’t you and which still remain.

May 22, 2012

Night Street by Kristel Thornell

I often wonder about the nature of the fictionalized biography, the kind of which Kristel Thornell has created in her first novel Night Street, which is based on the life of Australian artist Clarice Beckett. Though I realize any biography contains its own fair share of fiction, the blatant fictionalization makes me uneasy, it makes me seize on something that isn’t so and could lead to me going around in public spouting lies quite unaware. And then I wonder about my own wonderings, if they have any basis in a novel whose fiction is inspired by a real-life person I’ve never heard of. Do I put my wonderings away then? Does it even matter what is fact and fiction in a book that wholly creates everything I’ve ever known about this artist called Clarice Beckett? It’s kind of interesting to consider. Even more so when I think that this book was marketed to me as being an Australian literary award-winner, the Vogel Literary Award no less. Which I’ve never heard of either, but I take it as authority, and isn’t it funny how we do that? And I like it actually that I come to this book with no preconceptions at all.

I often wonder about the nature of the fictionalized biography, the kind of which Kristel Thornell has created in her first novel Night Street, which is based on the life of Australian artist Clarice Beckett. Though I realize any biography contains its own fair share of fiction, the blatant fictionalization makes me uneasy, it makes me seize on something that isn’t so and could lead to me going around in public spouting lies quite unaware. And then I wonder about my own wonderings, if they have any basis in a novel whose fiction is inspired by a real-life person I’ve never heard of. Do I put my wonderings away then? Does it even matter what is fact and fiction in a book that wholly creates everything I’ve ever known about this artist called Clarice Beckett? It’s kind of interesting to consider. Even more so when I think that this book was marketed to me as being an Australian literary award-winner, the Vogel Literary Award no less. Which I’ve never heard of either, but I take it as authority, and isn’t it funny how we do that? And I like it actually that I come to this book with no preconceptions at all.

I wanted to read Night Street because I’ve been dying for a novel, and also because we don’t get to read enough Australian writers in Canada (and when we do, I generally appreciate them. At the moment I’m thinking of Helen Garner). Thornell has apparently chosen to fictionalize most elements of Clarice Beckett’s life because Beckett was elusive by nature anyway, not terribly well known, and because Thornell wanted to blur the edges of her work as Beckett did with her own paintings, one of which is displayed on the novel’s front cover.

And when I read this book, I kept thinking of Katherine Mansfield, mostly because I read so little literature from Australia that New Zealand’s Mansfield is all I can come up with, also because Thornell’s treatment of Beckett’s life reminded me of Janice Kulyk Keefer’s Thieves, and because both Mansfield and Beckett came to tuberculotic fates, though that and approximate geography are about all they have in common.

Thornell’s Clarice Beckett (and I still have to make the distinction! I just can’t let it go) was not a woman of tumultuous passions, being wholly devoted to her art from a very young age. Painting was it from the very beginning, and so the decision to live at a remove from the rest of the world was never a difficult one to make. Her family’s reservations about her choices don’t bother her, she racks up rejected proposals without compunction, she builds a portable painter’s studio and wheels it out onto the beach and paints and paints as the rain falls down (which, as you might see, leads to the fate which befalls her). She has a couple of love affairs, but even these fail to permeate her focus, and her feelings towards her lovers are more aesthetic than erotic.

So it’s not so much Beckett’s edges that are blurry in this novel, but Beckett herself, whose remove from the world is also a remove from the book. She’s an unknown quantity. There is no friction driving the novel forward, which at times is frustrating, and yet the singularity of Beckett’s vision is the novel’s chief appeal. Everything she sees is in terms of tone, of light and colour. “Tone came in first. Apt and beautiful, the word tone for describing the stages of intensity of light and shade, gradations in luminosity being indeed every bit as subtle and sliding at the moods of a voice. ” Every person she speaks to, she’s peering past them, over their shoulders because landscape is the point always. “A distance off, the child, until then seated, unfolded, elongated and became kinetic: a small figure running away from the beach. Clarice noticed in herself a growing interest in the human form; perhaps physical love did that to you.”

A problem I often have with books about art is that I find myself unable to see what the text is describing, but this was not the case with Night Street. Thornell brings her images to life on the page, and uses language in way that is just as intriguing (“Silence flattered him like a high-class suit, a generously positioned lamp”). And it was refreshing to read a book that doesn’t rely on the same plot-points to turn on– pull between self and society, love or art, home or the world. For Thornell’s Clarice Beckett, it was only about art always, and Thornell has created a convincing portrayal of a woman so absorbed.

May 21, 2012

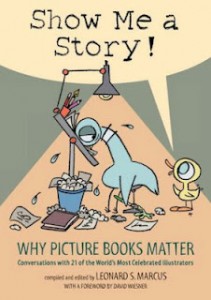

Show Me a Story: Why Picture Books Matter

Last Sunday, I had a the rare pleasure of walking into a bookshop, browsing awhile, and buying a book I had only just discovered. That book was Leonard Marcus’s Show Me a Story: Why Picture Books Matter, 21 Conversations with 21 of the World’s Most Celebrated Illustrators, which I bought not just for its cover art (a Mo Willems book for me!), but because the illustrators interviewed included Quentin Blake, John Burningham, Eric Carle, James Marshall, Robert McCloskey, Lois Ehlert, Helen Oxenbury, Maurice Sendak, Peter Sis, Rosemary Well, William Steig, and Willems himself, among others. The book was wonderful. I was amazed to learn that Oxenbury and Burningham are married, that Tana Hoban and Russell were siblings, Steig was incredibly grumpy, Blake said he could only draw automobiles that were falling apart, that George and Martha were inspired by Frog and Toad (but of course!). That Sendak was a mentor to so many others, and that picture book illustration was such an old boys’ network. I loved learning about how many illustrators had a background in graphic design, reading their ideas about fonts in picture books, how much of a role technology had– being able to do books in full colour changed everything. And now it’s a big deal when an illustrator wants to hold back a bit, do some pages in black and white. I also love that as I’m still a picture book novice, I can read a book like this and discover so many new authors and illustrators– the book is in alphabetical order, and first up was Mitsumasa Anno with whom I fell in love as soon as I hit the library.

Last Sunday, I had a the rare pleasure of walking into a bookshop, browsing awhile, and buying a book I had only just discovered. That book was Leonard Marcus’s Show Me a Story: Why Picture Books Matter, 21 Conversations with 21 of the World’s Most Celebrated Illustrators, which I bought not just for its cover art (a Mo Willems book for me!), but because the illustrators interviewed included Quentin Blake, John Burningham, Eric Carle, James Marshall, Robert McCloskey, Lois Ehlert, Helen Oxenbury, Maurice Sendak, Peter Sis, Rosemary Well, William Steig, and Willems himself, among others. The book was wonderful. I was amazed to learn that Oxenbury and Burningham are married, that Tana Hoban and Russell were siblings, Steig was incredibly grumpy, Blake said he could only draw automobiles that were falling apart, that George and Martha were inspired by Frog and Toad (but of course!). That Sendak was a mentor to so many others, and that picture book illustration was such an old boys’ network. I loved learning about how many illustrators had a background in graphic design, reading their ideas about fonts in picture books, how much of a role technology had– being able to do books in full colour changed everything. And now it’s a big deal when an illustrator wants to hold back a bit, do some pages in black and white. I also love that as I’m still a picture book novice, I can read a book like this and discover so many new authors and illustrators– the book is in alphabetical order, and first up was Mitsumasa Anno with whom I fell in love as soon as I hit the library.

“One of the most important things is to laugh with your children and to let them see you think they’re being funny when they’re trying to be. It gives children enormous pleasure to think they’ve made you laugh. They feel they’ve reached one of the nicest parts of you.” –Helen Oxenbury

May 17, 2012

Picture books in which animals are put in jail

This is something I’ve been thinking about for some time. It is by no means a comprehensive list.

Curious George by Margret and HA Rey: Early Curious George was not only an avid cigar smoker, but ends up in jail for making prank calls to the fire department. Being a monkey, he is able to escape from jail with relative ease when a prison guard stands on one end of George’s cot whilst chasing him and lifts the other end up to the window. He floats away in a balloon. Later, he stars in a movie.

Curious George by Margret and HA Rey: Early Curious George was not only an avid cigar smoker, but ends up in jail for making prank calls to the fire department. Being a monkey, he is able to escape from jail with relative ease when a prison guard stands on one end of George’s cot whilst chasing him and lifts the other end up to the window. He floats away in a balloon. Later, he stars in a movie.

Veronica by Roger Duvoisin: Veronica is a hippo who hates to blend into her herd (whose collective noun is actually “bloat”, but this isn’t part of the text). She gets around her camoflage by escaping to the city, but the gets hauled away for holding up traffic. The jail, unfortunately, barely contains her (speaking of bloat), and they have to bust down the doors to get her out of the place after a sympathetic little old lady comes to her aid and wins her freedom.

Chouchou by Francoise: Chouchou is a little French donkey who leads a simple but pleasant life having tourists pose with her for photographs. One day while provoked, however, she bites a young customer and is thrown in jail. She is only freed once the local children attest to her gentleness, demonstrating to officials that she’s indeed a harmless creature. She is freed in time to officiate at her photographer-owner’s wedding.

Chouchou by Francoise: Chouchou is a little French donkey who leads a simple but pleasant life having tourists pose with her for photographs. One day while provoked, however, she bites a young customer and is thrown in jail. She is only freed once the local children attest to her gentleness, demonstrating to officials that she’s indeed a harmless creature. She is freed in time to officiate at her photographer-owner’s wedding.