June 20, 2012

Cars Galore!

We’ve had Cars Galore by Peter Stein and Bob Staake out of the library for about six weeks now, and it’s starting to look like we’ll have to get a copy of our own. It’s a pretty simple concept, slick retro drawings of automobiles with accompanying rhyming couplets (and how we do love rhyming couplets). Some of the cars are pretty ordinary– fast and slow, on the go, but then the old car is wearing band-aids, which is fascinating if you happen to be three years old, and there’s a fort car, a shark car, and a Noah’s Ark car! “Honk cars! BEEP cars! At-a-creep cars. Miles of piles of in-a-heap cars.”

We’ve had Cars Galore by Peter Stein and Bob Staake out of the library for about six weeks now, and it’s starting to look like we’ll have to get a copy of our own. It’s a pretty simple concept, slick retro drawings of automobiles with accompanying rhyming couplets (and how we do love rhyming couplets). Some of the cars are pretty ordinary– fast and slow, on the go, but then the old car is wearing band-aids, which is fascinating if you happen to be three years old, and there’s a fort car, a shark car, and a Noah’s Ark car! “Honk cars! BEEP cars! At-a-creep cars. Miles of piles of in-a-heap cars.”

We’re a car-loving, road-tripping family, and we’ve never let not owning a car come between us and our love of driving. In fact, it’s probably a big reason for that love because we only get in a car about once a month, and so it’s always a special event when we do. And because we’re Autoshare members, it really has been cars galore around here. Harriet knows more about car brands than the average child from a carless household. We drove the Matrix for a long time, then the Prius, and were getting to be regular drivers of the Mazda 3, when we got a brand new car in our lot. (More about that new car in a sentence or two.) I especially love the “share” in Autoshare, that we get to show Harriet an example of sharing in action (keeping the car tidy, returning it on time, getting excited when we see other Autoshare cars out in the world) as she works hard to learn this vital skill for herself.

But yes, the car. How we do love “our” Fiat 500, whose awesomeness makes it entirely worth the effort required to get a car-seat into that tiny backseat. It’s red!, sporty, stylish, comfortable, fun to drive, and we like to shout, “Fiat 500!” whenever we’re on the road, to which the rest of the family responds with cheers. Indeed.

But yes, the car. How we do love “our” Fiat 500, whose awesomeness makes it entirely worth the effort required to get a car-seat into that tiny backseat. It’s red!, sporty, stylish, comfortable, fun to drive, and we like to shout, “Fiat 500!” whenever we’re on the road, to which the rest of the family responds with cheers. Indeed.

And we especially like that its radio seems to be playing Carley Rae Jepsen’s Call Me Maybe whenever we want it to be, which is always.

June 18, 2012

Books here and there

In the latest issue of UofT Magazine, I’ve got a short piece about Katrina Onstad’s new novel Everybody Has Everything:

In the latest issue of UofT Magazine, I’ve got a short piece about Katrina Onstad’s new novel Everybody Has Everything:

“Katrina Onstad ( MA 1999) might be best known for her national newspaper and magazine columns, but her debut novel How Happy to Be was celebrated for its satire, wit, and examination of loving and working in the 21st century. In her new novel, Everybody Has Everything, Onstad takes a similar approach, once again considering the isolating aspects of contemporary urban life. Through her characters James and Ana, she uses the perspective of a longchildless couple to take a provocative look at modern parenthood, illuminating the absurdity of a culture that has turned “parent” into a verb.” (Read the rest)

And my review of the picture book David Weale and Pierre Pratt’s Doors in the Air, which I loved, has just gone online at Quill & Quire:

And my review of the picture book David Weale and Pierre Pratt’s Doors in the Air, which I loved, has just gone online at Quill & Quire:

“In one of the final illustrations, the boy is perched atop an orange door like a flying carpet, on a journey to the moon. The accompanying text suggests there is no doorway more important than one’s limitless imagination, and drives home the book’s subversive and powerful message: ‘Remember, you don’t have to stay where you are.'” (Read the rest)

June 18, 2012

7 Years

We’ve got a sitter! Looking forward to dinner out tonight to celebrate 7 years since “I do”, and the success of not being remotely itchy.

We’ve got a sitter! Looking forward to dinner out tonight to celebrate 7 years since “I do”, and the success of not being remotely itchy.

“They would talk of such questions among books, or out in the sun, or sitting in the shade of a tree undisturbed. They were no longer embarrassed, or half-choked with meaning which could not express itself; they were not afraid of each other, or, like travellers down a twisting river, dazzled with sudden beauties when the corner is turned; the unexpected happened, but even the ordinary was lovable, and in many ways preferable to the ecstatic and mysterious, for it was refreshingly solid, and called out effort, and effort under such circumstances was not effort, but delight.” –Virginia Woolf, The Voyage Out

June 18, 2012

How to avoid being a spam-bot and change the world in the process

Two of the things I complain about most often in public are terrible examples of authors promoting their work online and women writers’ lack of representation in the media and in the world, and so it is amazing to me that both of these annoying things can be addressed with one solution.

But I will address the former problem first, those head-bangingly awful incidents in which it’s clear that authors don’t understand that the opportunity to shill their stuff an offshoot of social media engagement and not its primary purpose. Though I’ve met writers who go the other way, who get a poem published in a national magazine and think it’s bragging to put a link on Facebook. It isn’t. Linking to cool stuff is what people do on Facebook, on twitter and on blogs. But it’s when writers cross a line from, “Look at this!”” (link to published poem) to “Look at me!!” (link to published poem posted on twitter five times daily for months at a time, and also spamming link to other people’s feeds) that it gets to be a problem. When you’re a human who’s a spam-bot, you’ve clearly gone too far.

So how do you avoid becoming a human spam-bot? Easy: don’t post the same link more than twice. If you run out of links, do something new, something better. And in between those links, how about you talk about somebody who isn’t you? A book that isn’t yours? If you’re part of a literary community, you can talk about what your peers are up to. If you aspire to be part of a literary community, deposit yourself within it by engaging with that community’s literature online. If you’ve got nothing to do with any literary community, talk about the best books you’ve read lately and– ka-pow– you’ve just situated yourself in (close) relation to those books, those authors. It’s amazing. From these references, your readers will be able to figure out what you’re about.

When you have promotional opportunities– to write guest blog posts, to write your own blog, when you’re talking to a reporter or answering a Q&A– share your attention with other deserving writers and books. When someone puts a call out for book suggestions, resist to the impulse to chime in with “Mine!” and suggest somebody else’s. If there is a readers’ choice award going on, take a risk and champion a book that you didn’t write (which is the point of these things anyway. It’s not a “writer’s choice” award). If your book is up for a readers’ choice award, sit back and let the readers choose. (If you win a readers’ choice that you rigged, you didn’t win anything at all.) Engage with social media not just as a writer, but as a reader. It broadens your approach, and makes you that much more interesting.

And it also serves to promote a culture of readers, of reading. If you’ve already got someone’s attention, they know about your book, so why not suggest another? It increases the odds that whoever is listening will buy two books instead of one. And as a writer, you certainly stand to benefit when people start buying more books. When you reference other people’s books, it becomes less about your book than about reading in general, which is a terrifying leap to take, I know, but if your book is really good, it will only thrive in that healthy bookish eco-system. It means that you’re taking the opportunity to support other writers, and not in that annoying “rah-rah we all stick to together” way, but in that you have a platform from which to promote the work you really believe in, the books you’d like to see growing up alongside your own, the writing you admire.

And if you are a woman (and even if you’re not) and if the writing you admire happens to be written by women, then herein lies your chance to be part of the solution to the problem of women’s lack of representation in the media and the world. You don’t have to be a book reviewer or an editor to do something about it. You just have to be a reader as well as a writer, a reader/writer who champions the work of worthy women writers. Use your power as someone with a platform to shine a light on other books, other works. Support great work, be vociferous in that support, and understand how that support has greater impact when it’s a woman’s great work you’re supporting, that you’re helping to change the game for the better.

June 17, 2012

Sue Sorensen's A Large Harmonium

Please, let me tell you about Sue Sorensen’s A Large Harmonium, though it’s distinctly possible that I already did because I spent last week telling everyone about it, urging them to read it, this smart, hilarious book that delighted me so. “I say I will buy the Jiffy Markers myself,” is the novel’s first line, and I was hooked for Woolfish reasons and because I had no idea where a line like that might take me.

Please, let me tell you about Sue Sorensen’s A Large Harmonium, though it’s distinctly possible that I already did because I spent last week telling everyone about it, urging them to read it, this smart, hilarious book that delighted me so. “I say I will buy the Jiffy Markers myself,” is the novel’s first line, and I was hooked for Woolfish reasons and because I had no idea where a line like that might take me.

The line is delivered by Janet Erlicksen, a university English professor who’s on the cusp of a mild mid-life crisis. The novel begins in April with the school term ending and she must contemplate a summer before her without the scaffold of routine– what then to hang her days on? She considers writing an academic book about bad mothers in children’s literature, or penning a murder mystery in which her mother-in-law is the victim, or starting an online academic journal, but none of these ideas gets far off the ground. She’s also distracted by a sense that her husband Hector is in love with another woman, and she’s ever distracted by their three-year old son Little Max for whom distraction is a main occupation.

In 12 chapters, the novel takes us through Janey’s year month-by-month, incidents in her life, and those of her family and her friends, and it’s Janey’s voice and her humour that drives us, as well as turns in the plot that are never quite what you’d expect. And I love this novel quite simply because it’s doing all my favourite things: it’s funny, it shows a mother for whom motherhood is just part of a complex identity, it shows a rock-solid marriage (in spite of Janey’s suspicions), abortion shows up in the life of secondary characters but as a sad and ordinary thing rather than a plot-point, unabashed feminism shows up too, children’s literature is taken seriously, and it’s an academic satire that really is. (Janey presents a paper on the absence of talking animals in Canadian children’s literature. “It is far more fun to present a research project about something that is not there than something there is. I can get people riled up, outraged. Where are the talking animals? Who has repressed the talking animals? I could make my scholarly reputation.”)

Winnipeg resident Sorensen has much in common with Carol Shields, who was another, except that her tone is darker and more overtly hilarious. The novel’s pace is brisk and easy, which is not to say “light”, because there is depth here, but the story goes down just as well. Just as Shields did, Sorensen’s got a grasp on joy and how it factors amidst life’s absurdities. This is a wonderful novel with broad appeal. It’s absolutely the funniest and one of the best books I’ve read in ages.

June 14, 2012

I'm thinking about chick-lit circa 1995

I do wonder what it would have been like to publish a novel in 1995 about a flighty woman who works in an office and the tragic details of her romantic life. Especially if this was your second novel, the first having won the Whitbread First Novel Award. Think about it: Candace Bushnell was still a newspaper columnist, and Bridget Jones was just being born as the subject of an anonymous newspaper column. “Chick-lit” was nothing but the title of an edgy anthology of “postfeminist” fiction published by a university press.

I do wonder what it would have been like to publish a novel in 1995 about a flighty woman who works in an office and the tragic details of her romantic life. Especially if this was your second novel, the first having won the Whitbread First Novel Award. Think about it: Candace Bushnell was still a newspaper columnist, and Bridget Jones was just being born as the subject of an anonymous newspaper column. “Chick-lit” was nothing but the title of an edgy anthology of “postfeminist” fiction published by a university press.

Though there is not much about Rachel Cusk’s The Temporary that is chick-lit as we’ve come to know it. The writing, for starters. Chapter 3 begins: “Francine Snaith was lodged in the gloomy oesophagus of the Metropolitan Line, where her enjoyment of the single customary pleasure of underground travel– that of observing her reflection in the dark windows opposite her seat– had been obstructed since Baker Street by the disorderly herd of standing passengers which had been driven by overcrowding down the narrow corridor in front of her.” And that’s just a single sentence.

The book’s beginning is wonderful too, a strange and wonderful scene with Francine Snaith answering a ringing public telephone: “…being possessed of the conviction that destiny had it continually in mind at any moment to summon her, felt it was intended that she should answer.” Eventually, she decides that her destiny is Ralph, a man she meets at an art gallery launch who she imagines to be worldly and successful, though not as much as his friend whom she really fancies. It’s Ralph who calls her, however, this time on her own phone (and how much better is plot set in a pre-mobile phone world, don’t you think?), and from then on, the two are entangled.

Francine is a temp, and Ralph regards her as much of the same, a temporary salve for his loneliness, but once she sinks her paws into him, she’s reluctant to let go. Never mind that Francine doesn’t love him exactly as much as he disregards her, but he fills a vacuum in her life and she makes him do. Cusk illustrates the curious fact of how entire relationships can be enacted out of boredom. The book is told from both their points of view, in alternating chapters. Ralph himself is a bit pathetic but created with some sympathy, while Francine is stupid and a bit evil, and here is another chick-lit diversion, because how can a female protagonist not be lovable? But she isn’t.

There’s a lot of great work detail throughout the novel about the realities of life as a temp, about the uncertain foundation of one’s early twenties during which roommates and apartments are as fluid as identities. And like most of what Cusk writes, the book is also about class, about the enormous gap that exists between Francine and Ralph (or at least seems to. When Ralph’s humble origins are revealed to Francine, we see how baseless are the clues to these things, and yet what important signifiers they continue to be). It’s also a book about the city, about sweeping down streets with the tide, about being stuck in traffic, about being seen and being invisible, about being lost.

The Temporary these days would come complete with a pastel cover. But then so does Nancy Mitford, Jane Austen, Barbara Pym, all of these brilliant writers’ works reduced to their simplest most common denominator.

June 14, 2012

A Page From the Wonders…

This is the book I bought tonight in celebration of the Literary Press Group having their funding restored— Stephanie Bolster’s A Page From the Wonders of Life on Earth. The news was a surprise, and I’m only one of many readers who are overjoyed. You should be too, and your reading life will be better for this news, even if you don’t know it yet. And if you’d like to have a celebration of your own, I’d recommend any of the ones I mentioned in my original post, and also Sheree Fitch’s extraordinary new picture book Night Sky Wheel Ride, which Harriet shouts along to when we read it to her. Please also read Sheree’s gorgeous post on LPG funding and I dare you not to be moved.

This is the book I bought tonight in celebration of the Literary Press Group having their funding restored— Stephanie Bolster’s A Page From the Wonders of Life on Earth. The news was a surprise, and I’m only one of many readers who are overjoyed. You should be too, and your reading life will be better for this news, even if you don’t know it yet. And if you’d like to have a celebration of your own, I’d recommend any of the ones I mentioned in my original post, and also Sheree Fitch’s extraordinary new picture book Night Sky Wheel Ride, which Harriet shouts along to when we read it to her. Please also read Sheree’s gorgeous post on LPG funding and I dare you not to be moved.

June 14, 2012

Enter CWILA

I am inspired, excited and hopeful like I haven’t been in ages about Canadian Women in the Literary Arts (CWILA) which has apparently been simmering all spring and broke out into the world yesterday with a storm. A response to the American organization VIDA, CWILA has similarly compiled statistics about gender parity in book reviewing, and the results are predictably dismal. Less dismal, however, were particular statistics for Quill & Quire and THIS Magazine, whose parity negates the excuses of others as to why such a thing is impossible. It clearly isn’t. How wonderful.

I am inspired, excited and hopeful like I haven’t been in ages about Canadian Women in the Literary Arts (CWILA) which has apparently been simmering all spring and broke out into the world yesterday with a storm. A response to the American organization VIDA, CWILA has similarly compiled statistics about gender parity in book reviewing, and the results are predictably dismal. Less dismal, however, were particular statistics for Quill & Quire and THIS Magazine, whose parity negates the excuses of others as to why such a thing is impossible. It clearly isn’t. How wonderful.

From the site: “CWILA (Canadian Women in the Literary Arts) is an inclusive national literary organization for people who share feminist values and see the importance of strong and active female perspectives and presences within the Canadian literary landscape.”

It is an incredible honour to have such ranks to join.

June 12, 2012

Great City Picture Books

My love of city picture books continues, and these are some we’ve been enjoying lately, in particular for how they show the modern city in all its international multi-cultural richness.

Out of the Way! Out of the Way! by Uma Krishnaswami, illustrated by Uma Krishnaswamy (who are two different people! Really!). This wonderful, colourful book is Silverstein’s The Giving Tree meets Burton’s The Little House, but without the depressing saccharine of the former and the weird ending of the latter. A little tree sprouts in the middle of a path in an Indian town, and as a little boy kneels down to protect it, to admire it, passerbys in a hurry shout: “Out of the way! Out of the way!” The tree grows, the path bends to wind around it, and people come to sit under its branches, birds nest in the leaves, and a city grows up too around them as the path is steamrolled into a road whose traffic includes bicycles with dinging bells, bullock carts, and mango sellers shouting, “Out of the way! Out of the way!” The book gets bonus points for including fabulous pictures of the cars and trucks that crowd the streets, guaranteed to delight small readers (even a cement mixer!), and also for leaving the tree standing, a place for quiet and contemplation in the middle of the bustling city space.

Out of the Way! Out of the Way! by Uma Krishnaswami, illustrated by Uma Krishnaswamy (who are two different people! Really!). This wonderful, colourful book is Silverstein’s The Giving Tree meets Burton’s The Little House, but without the depressing saccharine of the former and the weird ending of the latter. A little tree sprouts in the middle of a path in an Indian town, and as a little boy kneels down to protect it, to admire it, passerbys in a hurry shout: “Out of the way! Out of the way!” The tree grows, the path bends to wind around it, and people come to sit under its branches, birds nest in the leaves, and a city grows up too around them as the path is steamrolled into a road whose traffic includes bicycles with dinging bells, bullock carts, and mango sellers shouting, “Out of the way! Out of the way!” The book gets bonus points for including fabulous pictures of the cars and trucks that crowd the streets, guaranteed to delight small readers (even a cement mixer!), and also for leaving the tree standing, a place for quiet and contemplation in the middle of the bustling city space.

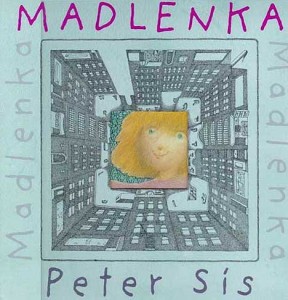

Madelenka by Peter Sis: Not a new book, but new to us, about a little girl who lives “in the universe, on a planet, on a continent, in a country, in a city, on a block, in a house, in a window, ” and she is Madlenka and her tooth is loose. Sis’s drawings give us a bird’s eye view of the block as Madlenka goes through the neighbourhood sharing her news. Each of the shopkeepers she encounters comes from a different place– the baker from France, the newsagent from India, the Italian ice-cream man, the German neighbour Mrs. Grimm who knows so many stories. In some cases, we’re granted a tour of the shops in questions, and also a visual representation of the stories Madlenka has told to her: the South American grocer’s jaguar legends, her Asian neighbours stories of dragons, and even the fantasy world that she’s invented with her school friend Cleopatra which transforms their courtyard into the African savanna. The tooth gets lost and Madlenka goes home to report that in connecting with her neighbours she has been around the world. (You can take a virtual tour of the book on Peter Sis’s website).

Madelenka by Peter Sis: Not a new book, but new to us, about a little girl who lives “in the universe, on a planet, on a continent, in a country, in a city, on a block, in a house, in a window, ” and she is Madlenka and her tooth is loose. Sis’s drawings give us a bird’s eye view of the block as Madlenka goes through the neighbourhood sharing her news. Each of the shopkeepers she encounters comes from a different place– the baker from France, the newsagent from India, the Italian ice-cream man, the German neighbour Mrs. Grimm who knows so many stories. In some cases, we’re granted a tour of the shops in questions, and also a visual representation of the stories Madlenka has told to her: the South American grocer’s jaguar legends, her Asian neighbours stories of dragons, and even the fantasy world that she’s invented with her school friend Cleopatra which transforms their courtyard into the African savanna. The tooth gets lost and Madlenka goes home to report that in connecting with her neighbours she has been around the world. (You can take a virtual tour of the book on Peter Sis’s website).

A Bus Called Heaven by Bob Graham: We love Bob Graham and his heartwarming stories of community in urban places (though they’re often more inner-suburban, run-down homes, shuttered shops and factories next to grassy yards). His books are also just a little bit strange, poetic and surprising. They’re edgy in the softest way, and Harriet is entranced with this latest one, the story of an abandoned bus that transforms a city street. With no idea where the bus arrived from, neighbours haul it off the road and into Stella’s driveway. Shy Stella is transformed herself as the bus is turned into a community hub, everybody doing their part to make it beautiful. Now there is a place for people to gather and connect, Graham’s illustrations showing neighbours of all different cultures and backgrounds together. And when regulations about busses protruding into the sidewalk threaten to spoil the show, it is Stella who saves the day (and the snails. And the sparrows). We love this book.

A Bus Called Heaven by Bob Graham: We love Bob Graham and his heartwarming stories of community in urban places (though they’re often more inner-suburban, run-down homes, shuttered shops and factories next to grassy yards). His books are also just a little bit strange, poetic and surprising. They’re edgy in the softest way, and Harriet is entranced with this latest one, the story of an abandoned bus that transforms a city street. With no idea where the bus arrived from, neighbours haul it off the road and into Stella’s driveway. Shy Stella is transformed herself as the bus is turned into a community hub, everybody doing their part to make it beautiful. Now there is a place for people to gather and connect, Graham’s illustrations showing neighbours of all different cultures and backgrounds together. And when regulations about busses protruding into the sidewalk threaten to spoil the show, it is Stella who saves the day (and the snails. And the sparrows). We love this book.

June 11, 2012

Magnified World by Grace O'Connell

“And as navigate the city at the centre of the map, we realize that we, too, are part of the story, crafting new narratives of Toronto even as the city swirls and eddies around us like a buried river brought back to life.” –Amy Lavender Harris, Imagining Toronto

“And as navigate the city at the centre of the map, we realize that we, too, are part of the story, crafting new narratives of Toronto even as the city swirls and eddies around us like a buried river brought back to life.” –Amy Lavender Harris, Imagining Toronto

Recent Toronto books, including Sean Dixon’s The Many Revenges of Kip Flynn, Alissa York’s Fauna, Claudia Dey’s Stunt and Maggie Helwig’s Girls Fall Down are remarkable for not just their Toronto settings, but for how their authors engage with the city as myth-makers, building on old myths (and yes, ravines are useful for this) and also for creating new ones. For imagining a Toronto beyond Toronto, an other city that looks like ours but shimmers in a different way, in a way that makes us look at the city twice.

Toronto is engaged with in just this way in Magnified World, the first novel by Grace O’Connell who is Random House Canada’s 2012 New Face of Fiction. It is a story told by Maggie Pierce who enters page one wearing unfamiliar shoes and stumbling home without a clue as to where she’s spent the night. Her home is an apartment above Pierce Gifts & Oddities, her mother’s shop on Queen Street West (with tin ceilings!) across from Trinity Bellwoods Park in the late 1990s, a period in which the neighbourhood was on the cusp of significant change. Maggie’s most significant change, however, has been her mother’s death just weeks before by drowning in the Don River, her pockets full of zircon stones from the shop.

“For the first few weeks, I forgot sometimes that she was dead; not completely, of course, but in little, individual moments, when I would see the yellow zucchini she liked in a store,or smell the rooibus tea she drank. If they were still selling these things, if they existed, then she must be alive, to eat, to drink.”

We begin to see that Maggie was at a remove from the world even before her mother’s death, having spent most of her time working in the shop and caring for mother through her mental health troubles. Her parents’ marital problems have alienated her professor father from the household in all but body, and Maggie’s only other connections are her best friend Wendy and boyfriend Andrew, both of whom are making their own ways and growing away from her. And so when she starts suffering from blackouts and delusions, it’s almost part of a pattern, Maggie moving farther and father away from the world. She doesn’t react in the way we think she might, but it’s a testament to how alone she is, how grief-stricken she is by the loss of her mother. She seeks help from a psychiatrist at the nearby CAMH hospital, but then is taken in by his enigmatic colleague who promises answers and seems to have ulterior motives. All the while, she’s being visited by a familiar stranger named Gil who calls her “darling”, wants to write the story of her life, and may or may not actually exist.

The novel lags in its second third as Maggie’s blackouts and visions begin to seem a convenient way for the novel to evade any real explanation of what’s going on. The farther she gets from reality, the more implausible becomes the behaviour of the people around her, which sort of makes sense, but not entirely, and doesn’t make for spectacular reading either. But then the novel picks up speed again in its final third as Toronto becomes a character, a body: “Below was the Don, flowing like a great vein. If the city were a body, this was where you would draw blood.” The city is most alive in a wonderful scene in which Maggie walks the streets of a downtown which is about to experience its own blackout: “The streetcar went by and then another, and another, like synapses, like the city thinking of itself.”

Sometimes the language got away from itself. I struggled with awkward similes like, “I let myself spread out, mentally checking the city like a tongue running over the empty socket of a tooth,” but these instances were conspicuous in their rarity, against the general strength of O’Connell’s prose. And my reservations about aspects of the story were gone by the novel’s end, as I realized how much Magnified World was a novel about the city, about being alone in the midst of millions of people, but the hope implicit in that it’s not really being alone after all.