July 4, 2012

The City's Sublime

If ever there was a centre to my personal geography, I suspect that the Toronto Islands would be it. My grandparents used to take me there– I remember the day they bought me a $13 day-pass to the Centreville amusement park, and it felt like being handed a key to the world. I’ve rode that ferry with at least 3 different boyfriends, which is particularly significant when you note how few boyfriends I’ve ever had in total. The Islands were key to my development as a feminist, as a person— I remember the liberation of fleeing the city on my bicycle to read Mrs. Dalloway on a south-facing beach, and how no one in the whole world knew where I was. Later that same summer, I swam naked at Hanlan’s Point and felt more powerful and fabulous than I had ever felt in my life.

If ever there was a centre to my personal geography, I suspect that the Toronto Islands would be it. My grandparents used to take me there– I remember the day they bought me a $13 day-pass to the Centreville amusement park, and it felt like being handed a key to the world. I’ve rode that ferry with at least 3 different boyfriends, which is particularly significant when you note how few boyfriends I’ve ever had in total. The Islands were key to my development as a feminist, as a person— I remember the liberation of fleeing the city on my bicycle to read Mrs. Dalloway on a south-facing beach, and how no one in the whole world knew where I was. Later that same summer, I swam naked at Hanlan’s Point and felt more powerful and fabulous than I had ever felt in my life.

I spent my 26th birthday on Ward’s Island, with friends who braved a 90 minute-long wait at the ferry docks because I didn’t have a phone so they couldn’t call to cancel once they wait had got ridiculous. We had dinner at the Rectory Cafe on our 3rd anniversary, and it was really the most tremendous thing, to jump on a ferry boat after work, such an extraordinary way to spend a Wednesday. We’ve taken out of town guests there, had picnics with friends, partaken many times in Wards Island ice cream, played frisbee, rode our bikes, once lost a three-legged race at a company picnic (against children), and shivered and swam in the lake.

We’ve gone every year at least once since Harriet was born, though our visit last weekend was the first one in which she was old enough to appreciate island goodness. We all love the ferry boats, which we know best from Allan Moak’s Big City ABC (I being for Island Ferry, of course). We spent our morning at Centreville, whose day-pass hasn’t been $13 for many years, but is still great value and we had a wonderful time riding the carousel, log flume, tea-cups, train, swan-boats and antique cars. Harriet couldn’t quite fathom that she’d entered a world in which she was permitted to drive.

After, we had our picnic on the banks of the lagoon, bread and cheese and fresh strawberries, then took a trek over to the Franklin Children’s Garden where Harriet had a fabulous time spotting the characters she knows from the Franklin books, watering the plants in the garden plots, and tracing her way along the snail trail. Then it was time for splash-padding and sand-digging, and re-applying our sunscreen. As the day got long, we took a long walk along the boardwalk to the Rectory Cafe for dinner. And when we were finished, we approached the Ward’s Island docks just as the boat was arriving which we boarded so it could take us home, exhausted but revelling in the goodness of a perfect day.

“Neither entirely land or water, but containing elements of both, the Toronto Islands are a fitting site for memorial rituals because their fluctuating sands reflect the fleeting passage of life, buffeted by storms of fortune and bracketed by the permeable border between here and the hereafter… Without mountains to serve as an urban muse, the islands have become the city’s sublime. Visiting the islands, valuing them, Torontonians experience something truly akin to transcendence.” –Amy Lavender Harris, Imagining Toronto

July 3, 2012

Stony River by Tricia Dower

It was funny to be reading Tricia Dower’s Stony River this morning, sprawled on the grass under trees at the park while Harriet played in the wading pool, to be as blissed out as the girl on the cover appears to be. And as that cover might suggest, this is indeed an ideal book for a summer long weekend, to curl up on the grass with, or on the dock, or on a towel on the beach. The book opens up with an irresistible literary map, so you can choose to navigate Stony River or simply get lost in it.

It was funny to be reading Tricia Dower’s Stony River this morning, sprawled on the grass under trees at the park while Harriet played in the wading pool, to be as blissed out as the girl on the cover appears to be. And as that cover might suggest, this is indeed an ideal book for a summer long weekend, to curl up on the grass with, or on the dock, or on a towel on the beach. The book opens up with an irresistible literary map, so you can choose to navigate Stony River or simply get lost in it.

I interviewed Tricia Dower in 2008, after the publication of her first book, the short story collection Silent Girl. Dower’s new book expands upon Silent Girl‘s first story, and is also connected to the book in other more surprising ways. Each of Silent Girl‘s stories took its cue from a Shakespearean play, but with a contemporary, feminist spin, and Dower took great leaps and risks in writing in a wide range of voices. Similarly, Stony River has a theatrical/cinematic feel, a sense of epic, of grandness, and Dower is ambitious in her approach, tackling crime fiction, riffing on True Romance, writing men and women, children and adults, and considering topics including domestic violence, depression, incest, religion, the supernatural, and murder.

Though Stony River seems at first an unlikely backdrop for such a story. A sleepy New Jersey town in the 1950s, most of what happens tends to go on behind closed doors. But one door is busted open on a hot summer day when 12 year-old Linda Wise and her tough-girl pal Tereza witness a young girl and baby boy being removed by the police from the home of “Crazy Haggerty,” a local character who’d been assumed all these years to live alone. When the crazy man dies, however, the existence of the girl–his daughter– and her son come to light, kept prisoner in his house for years, the younger child likely to be a product of incest. Linda and Tereza learn details of the case from the newspaper, and it sets off a chain of events that spins the girls’ lives far apart but also keeps them irrevocably bound.

The unknown girl is Miranda, who is cast into a world she’s only heard about from the books her father urged her to read from his expansive library. She finds refuge with the wife of a local police officer, who stays close to Miranda even after she’s sent to a Catholic orphanage to live with her son. Miranda is urged by everyone to confirm the identity of her son’s father, but she refuses to, insisting that his conception had been by divine intervention. Turns out her father had been a worshipper of various pagan gods and goddesses from his Irish homeland, and Miranda carries with her a special kind of vision. Her religious passion seems easily transferable to her Catholic surroundings, and soon the nuns admit that she possesses a strange connection to God. They’re urging her to become a nun herself, to give up her son and begin life anew, and Miranda refuses to.

Miranda’s sections of the novel are narrated in present tense, providing a sense of immediacy that makes sense as we see her discovering the world around her, whereas Tereza and Linda’s sections are in past tense, the ’50s in sepia tones, rife with cultural references. Tereza is already a girl in trouble and she sees Crazy Haggerty’s now-abandoned house as a perfect place to hide from her abusive stepfather. Whilst hiding, she discover’s Haggerty’s enormous stash of cash, and uses it to skip town for good, running away with a boy she’s met at the White Castle who has a shady past, is a devotee of Charles Atlas, and whose well-intentioned grandmother is happy to put her up for a while.

Meanwhile, Linda stays put in Stony River, wondering what became of her spirited friend, attempting to please her unhappy mother and trying desperately to conform to the 1950s’ expectation of womanhood that Tereza never bothered to understand, Tereza who’d preferred to imagine herself as a Hollywood starlet. One evening Linda gets into a car with an unknown man and is assaulted in the woods, and is left alone to deal with the fear and shame of her experience because she has no one to tell, and because anyone she did tell would protest that she’d been “asking for it.”

But when young girls begin to go missing around Stony River, Linda can longer permit herself to stay silent, putting her reputation on the line to bring her assaulter to trial, unknowingly also bringing herself back into Tereza’s orbit, and Miranda’s too. There turn out to be parallels between Linda’s ordinary life and Tereza and Miranda’s more extraordinary ones, and as ever, it turns out that nothing is quite what it seems.

Dower’s writing is excellent, her period details wonderfully wrought, a sense of place and time absolutely evoked. The novel is bursting with its seams with story and plot, though sometimes the plot fits too tidily into place and the seams themselves are too visible. With so many characters too, it’s not surprising that some are flat, that they all aren’t drawn with the depth of Miranda. And it’s true that after the novel’s mid-point, its pacing begins to fall off a bit, that you’ll wonder where the story is going. But, if you’re lucky, you’ll find yourself sprawled on the grass like I was, or on the dock, or on the beach as the novel begins to reach its conclusion. And then you won’t be able to put it down, caught up in the drama, the intrigue, and the feeling– the joy of a perfect summer read.

July 1, 2012

The seas inside my soul

As a rule, the seas inside my soul are so far from frozen, which is why I always roll my eyes at the Kafka quote about the book as ice-axe. And it occurs to me that while I have no need for an ice-axe, that perhaps I tend to employ my books as paddles, life buoys, fishing nets, and also that what I want from a book more than any other thing is for it to grab my soul and hold it steady for awhile.

As a rule, the seas inside my soul are so far from frozen, which is why I always roll my eyes at the Kafka quote about the book as ice-axe. And it occurs to me that while I have no need for an ice-axe, that perhaps I tend to employ my books as paddles, life buoys, fishing nets, and also that what I want from a book more than any other thing is for it to grab my soul and hold it steady for awhile.

June 28, 2012

On Barbara Reid's The Party, and devilled eggs, Joan Didion and cousins

I was born into a family already stocked with aunts and uncles, lots of cousins. And while I was about two decades too late for the party-going as captured in Barbara Reid’s The Party (which has a ’50s/’60s vibe), I can tell you that my grandparents were still hauling around the same cooler, same chairs, bowls full of dip and tins full of squares by the time I came along. I know what it’s like to confront a backyard full of cousin/strangers who are so familiar by day’s end that saying goodbye is a tragedy. And that menu! One day I want to have a The Party party just so that I can serve all the staples: “There’s sausage roles, casseroles, pineapple rings. Devilled eggs, chicken legs, little cheese things. Salads with jelly, salads with beans. Enough? Let the dog lick your party plate clean.”

I was born into a family already stocked with aunts and uncles, lots of cousins. And while I was about two decades too late for the party-going as captured in Barbara Reid’s The Party (which has a ’50s/’60s vibe), I can tell you that my grandparents were still hauling around the same cooler, same chairs, bowls full of dip and tins full of squares by the time I came along. I know what it’s like to confront a backyard full of cousin/strangers who are so familiar by day’s end that saying goodbye is a tragedy. And that menu! One day I want to have a The Party party just so that I can serve all the staples: “There’s sausage roles, casseroles, pineapple rings. Devilled eggs, chicken legs, little cheese things. Salads with jelly, salads with beans. Enough? Let the dog lick your party plate clean.”

It makes me sad that Harriet is unlikely to know the abundance of cousins that I did (and any cousins she might have will live a 5 hour plane journey away from on either side of us), that Barbara Reid’s The Party is a foreign storybook land. Joan Didion’s wrote this about her daughter in “On Going Home”: “I would like to give her more. I would like to promise her that she will grow up with a sense of her cousins and of rivers and of her great-grandmother’s teacups, would like to pledge her a picnic on a river with fried chicken and her hair uncombed, would like to give her home for her birthday, but we live differently now.” And we do.

Though my beloved cousin, who is my oldest friend, has a little girl who is five months younger than Harriet. They see one another just a few times a year, which means they’ve probably met about six times in their lives, but every time, they’ve adored each other and that delights me. That Harriet will know the bonds of cousinship. And then two weekends ago, on the other side of the family, my aunt and uncle invited everybody in the family to spend a sunny afternoon at their farm. These days, we usually only meet at funerals, and the family tree has grown so many branches of its own and with our grandparents gone, it’s hard to get everyone together. But we did, and it was glorious, and Harriet met aunts, uncles and cousins for the very first time, all these people who are a part of who she is, and there was even devilled eggs and bean salads, and a sky that shone like plasticine.

June 27, 2012

The Forrests by Emily Perkins

New Zealand author Emily Perkins’ last book was 2008’s Novel About My Wife, a curious and absorbing novel about a woman with a mysterious past who remains unknowable to her husband, and how motherhood seems to bring about her undoing. On the surface, it was an easy book, accessible, full of familiar references; and yet something so strange was going on under the surface, such darkness, an ambiguity that was frustrating and also thoroughly engaging. It was a novel that didn’t wear its literary-ness on its sleeve, but something underlying seemed to suggest that Emily Perkins was no ordinary author.

New Zealand author Emily Perkins’ last book was 2008’s Novel About My Wife, a curious and absorbing novel about a woman with a mysterious past who remains unknowable to her husband, and how motherhood seems to bring about her undoing. On the surface, it was an easy book, accessible, full of familiar references; and yet something so strange was going on under the surface, such darkness, an ambiguity that was frustrating and also thoroughly engaging. It was a novel that didn’t wear its literary-ness on its sleeve, but something underlying seemed to suggest that Emily Perkins was no ordinary author.

And with her latest, The Forrests, that fact is established. The novels starts off slow and it’s hard to find one’s footing in the narrative, mostly because there isn’t a narrative yet. We are treated to scenes from a childhood, from an eccentric family. The Forrests are four children, including two sisters Dorothy and Evelyn, so close that they’re practically twins, and their parents whose lapses in responsibility are painfully obvious to their children. The parents break up, then reconcile, and their children mostly make their own way, rudderless. Dorothy marries young, and Evelyn drifts, and both are irrevocably bound to Daniel, a family friend who is part-lover, part-brother to both of them.

The novel finds its plot in adulthood, in much the way life does. Perkins is particularly adept at showing the peculiar connections of marriage and motherhood, and how these impact the sisters who are living parallel lives. Gradually, the novel’s focus becomes Dorothy only, illustrating the unsustainability of family as an institution, or at least of this family. I found it curious to note that The Forrests contains secondary characters called Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy, all of them peripheral and never interacting with one another– the modern family and its connections are fragmented, illusory.

We follow Dorothy through the storm of motherhood, into middle age, to old age, to the point at which “time becomes measurable.” Perkins has not fixed her novel in time with many specific cultural references, and so the story has a contemporary feel from the start, a sense of immediacy. And as Dorothy’s awareness begins to diminish as she ages, we see that the seemingly random scenes at the novel’s beginning were actually the pivotal moments of her life in the grander context, the flashes of light that will remain when everything else is confused and dark.

The Forrests is like The Stone Diaries, but edgier, and structured as the interior of its subject’s mind rather than her scrapbooks, and it’s enormously successful. Rachel Cusk, Virginia Woolf. Vividly human characters, gorgeous writing. It’s full of surprises, twists, turns and moments of illumination, quiet but profound in its brilliance, and devastating to have to finally put down.

June 26, 2012

Bye Bye Butterflies

Since the last time we talked about Andrew Larsen, having become big fans of his award-winning book The Imaginary Garden, we’ve also become big fans of Andrew Larsen himself. We live in the same neighbourhood and always delight in seeing him, and so it was a particular joy when a few weeks back, he hand-delivered us a copy of his latest book Bye Bye Butterflies.

Since the last time we talked about Andrew Larsen, having become big fans of his award-winning book The Imaginary Garden, we’ve also become big fans of Andrew Larsen himself. We live in the same neighbourhood and always delight in seeing him, and so it was a particular joy when a few weeks back, he hand-delivered us a copy of his latest book Bye Bye Butterflies.

It’s a story, he told us, that would have particular resonance as Harriet’s gearing up to go to play school in September. Because it’s a story about Septembers, and Junes, and seasons that go round and round, of the things we long to hold onto but have to instead set free in the world. It begins with a little boy called Charlie who’s walking down the street with his dad and in a moment of silence, they hear sounds from the rooftop of a neighbouring school. Shouting children and then, at once, a swarm of butterflies are released into the sky and it’s as though the world is transformed for a little while, then it’s like nothing ever happened.

And Charlie too forgets about this incredible experience, as he starts school himself, as the seasons change and he gets bigger. And then his class begins a new project, raising caterpillars, and eventually, he finds himself on the school rooftop ready to set his butterfly free. “The children felt a little happy and a little sad all at once.” And then the butterflies go, and Charlie peers down to the street and sees another boy gazing up at him and the butterflies, standing just where he’d been with his dad a year before. And so the cycle begins again…

“Our new friends will be with us for just a few days… Then we will have to release them,” says Charlie’s teacher as the butterfly project begins, and of course Larsen’s book is not just about a butterfly’s life cycle only. It’s a story to help young children understand the steps involved in transitioning to big kid, and subtly captures the bittersweet, wonderful-terrible experience of being a parent and having to look on while this transition occurs, as our babies learn to fly away from us.

The idea of happy and sad all at once too is one that struck Harriet as quite profound, and she talked a lot about this after the fact. “Did you know, Mommy,” she said to me, “that something can be happy and sad altogether?” And it’s true that even as adults, we have a hard time getting our heads around this thought, so it was interesting for me to ponder too, and I love how Larsen’s books acknowledge the complexity of the world with such grace and simplicity, rendering these big ideas graspable, the world fixed, if only for a moment.

Check out illustrator Jacqueline Hudon-Verrelli’s blog, with lots of Bye Bye Butterflies in process. Design-wise and visually, the book is wonderful, and I love that it comes stamped with a large warning on its backside: “LIVE CONTENTS. OPEN IMMEDIATELY.” Orders I’d urge any reader to follow fast.

June 25, 2012

The Vicious Circle reads Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

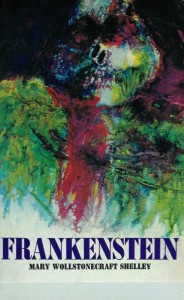

Comparing covers is one of my favourite parts of being in a book club, and I was overjoyed at our meeting last week to see that one of my comrades had brought along the crazy psychedelic edition that I read in university and had completely forgotten the look of. This time around, I’d bought a very respectable Modern Library edition (see below) whose previous owner had only yellow-highlighted a few random lines in chapter five.

Comparing covers is one of my favourite parts of being in a book club, and I was overjoyed at our meeting last week to see that one of my comrades had brought along the crazy psychedelic edition that I read in university and had completely forgotten the look of. This time around, I’d bought a very respectable Modern Library edition (see below) whose previous owner had only yellow-highlighted a few random lines in chapter five.

Anyway, I’m off track already, which is okay, because Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a bit heavy on the preamble anyway. (I made a chart: there are at least five stories in a story in this story, maybe six.) We didn’t have a roaring fire to gather ’round last Tuesday night, but we didn’t need one because it was so hot you’d sweat sleeping. We met up in the East End in one of the finest backyards in the city, and ate cheese, cherries, and strawberry bread, and drank just as much as we should have.

We got to talking about this book and Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin, about a person dealing with the implications of having created a murderous monster, and considering whether or not the monstrousness was innate or the result of the creator’s lack of naturing. (You, my creator, abhor me; what hope can I gather from your fellow-creatures, who owe me nothing??” says Frankenstein’s monster at one point.) We spend a long time arguing about whether we were talking about Frankenstein or his monster when we said “Frankenstein”, and 50% of the time, we meant the other. Which is funny because of how they became the same creature eventually, how Mary Shelley might have planned that confusion.

We got to talking about this book and Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin, about a person dealing with the implications of having created a murderous monster, and considering whether or not the monstrousness was innate or the result of the creator’s lack of naturing. (You, my creator, abhor me; what hope can I gather from your fellow-creatures, who owe me nothing??” says Frankenstein’s monster at one point.) We spend a long time arguing about whether we were talking about Frankenstein or his monster when we said “Frankenstein”, and 50% of the time, we meant the other. Which is funny because of how they became the same creature eventually, how Mary Shelley might have planned that confusion.

Is Victor Frankenstein sympathetic? And we were fortunate this night to have a Frankenstein scholar in our midst, who has written actual books on the subject, so we ended up talking about blow jobs a lot less than usual and instead discussed Victor as a man who truly doesn’t understand the consequences of his actions. We talked about the monster as self-taught (and how we loved that he took fiction as history, what it means to see the world that way), as representative of the limits of what one can do with one’s self, analogous with what a woman could do with herself in the early 19th century. And Mary Shelley herself, her biography, kept coming into this conversation. Author’s biography means more to a classic than to a contemporary work. Or does it… How we keep comparing the book to contemporary novels, because there was nothing else like it in its time, how it was a pointed response to the Romantics.

We talked about Walton the Polar Explorer, and Victor Frankenstein, of their senses of themselves as loners, as heroes, but that they’re both self-indulgent and controlling, messing with other people’s lives. It’s only their complete disregard of others which allows them to cast themselves as selfless heroes at all. How the miracle of Victor’s singular creation is something that women do all the time. Frankenstein and motherhood– apparently Shelley wrote the novel while she was pregnant. In a few weeks. Though novels are always becoming engulfed in these sorts of legends– it’s just another ring around the kernel of the story.

We talked about how Victor and the monster’s voices become more and more alike as the novel progresses, about how Victor seems set up for some of the monster’s crimes and how they’re so connected by that point that it doesn’t matter who killed who, their crazy symbiotic relationship in which neither can live without the other and Victor virtually sacrifices his bride as bait for his obsession. How the monster’s own dawning consciousness was like a baby’s, but that he’s never allowed to evolve into a human being. How you can never escape what you look like, how monsters bring out the monstrosity in others. We wondered about Mary Shelley whose own mother died in childbirth. Who was her monster?

And then the very last note I took was without context, “Hemingway was the John Irving of his time” and we’d lost the plot by then. We started yelling about 50 Shades and the state of publishing, and so it seems most appropriate just to leave it there.

June 25, 2012

Summer summer at 49thShelf

I’m in love with the main page of 49thShelf this week, with its Summer Summer list front and centre. Images of docks, beaches, summer reading, barbecues, the Beach Boys and a swing. I’m looking forward to reading Tricia Dower’s Stony River in the next week or so– I enjoyed her first book and interviewed her in 2008. Right now I’m reading Emily Perkins’ The Forrests, which starts slow but becomes enthralling. Also, I received Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl for my birthday, which is my cottage reading set. She’s got blurbs by Kate Atkinson, Kate Christensen and Laura Lippman, which is some pedigree, I think. Can’t wait to be beach-side with this one.

I’m in love with the main page of 49thShelf this week, with its Summer Summer list front and centre. Images of docks, beaches, summer reading, barbecues, the Beach Boys and a swing. I’m looking forward to reading Tricia Dower’s Stony River in the next week or so– I enjoyed her first book and interviewed her in 2008. Right now I’m reading Emily Perkins’ The Forrests, which starts slow but becomes enthralling. Also, I received Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl for my birthday, which is my cottage reading set. She’s got blurbs by Kate Atkinson, Kate Christensen and Laura Lippman, which is some pedigree, I think. Can’t wait to be beach-side with this one.

June 24, 2012

On slow-reads, and Robertson Davies' The Rebel Angels

I spent most of last week reading Robertson Davies’ The Rebel Angels upon the recommendation of my book club-mate Patricia, who mentioned it after we’d read Lucky Jim and talked about campus lit. And it is just a coincidence that I’d read it after Sue Sorensen’s A Large Harmonium, which was another campus satire, and also mentioned Patient Griselda, who I’d never even heard of (and which is really a terrible story, actually). It also mentioned Cornelius Agrippa, who I’d read about in Frankenstein, the other book I’ve just finished. And then there were the references and allusions I didn’t get or didn’t pick up on, and there were plenty. But I still enjoyed The Rebel Angels very much, my first Robertson Davies beyond the Fifth Business I read in school. It’s a slow read though, slow to start and packed with detail. And because I’m a notorious speedy reader, it was a bit hard to get used to the pace. To just let myself give into it, to stop thinking that slowness was a problem, or a sign of one. To be patient and realize that I really do have all the time in the world to get through it, that the other books can wait. To realize that this book was demanding time and patience of me, but delivering richness in rewards. And it did.

I spent most of last week reading Robertson Davies’ The Rebel Angels upon the recommendation of my book club-mate Patricia, who mentioned it after we’d read Lucky Jim and talked about campus lit. And it is just a coincidence that I’d read it after Sue Sorensen’s A Large Harmonium, which was another campus satire, and also mentioned Patient Griselda, who I’d never even heard of (and which is really a terrible story, actually). It also mentioned Cornelius Agrippa, who I’d read about in Frankenstein, the other book I’ve just finished. And then there were the references and allusions I didn’t get or didn’t pick up on, and there were plenty. But I still enjoyed The Rebel Angels very much, my first Robertson Davies beyond the Fifth Business I read in school. It’s a slow read though, slow to start and packed with detail. And because I’m a notorious speedy reader, it was a bit hard to get used to the pace. To just let myself give into it, to stop thinking that slowness was a problem, or a sign of one. To be patient and realize that I really do have all the time in the world to get through it, that the other books can wait. To realize that this book was demanding time and patience of me, but delivering richness in rewards. And it did.

Whereas Frankenstein, the book I read before it, was a book with a deadline, to be read before our book club meeting last Tuesday. On Saturday evening, when I’d only read 30 pages, it wasn’t really looking likely that I was going to get it read, and so I got down to it. I read most of Frankenstein in 24 hours, and what a joy to get so solidly inside a book, to take it in in almost one gulp, without distractions. Speedy reading can be wonderful.

But yes, there is a place for slowness, for stories that have to steep. I’m grateful to Robertson Davies for reminding me of that.

June 21, 2012

The Girl Giant

Kristen den Hartog’s novel And Me Among Them was one of my favourite books of last year, and my admiration for its author was only intensified when I met her in November for an interview. It’s a quiet book but, like its protagonist, And Me Among Them has made an impact on the world– it was shortlisted for the 2012 Trillium Book Award, and was just awarded the Alberta Trade Fiction Book of the Year Award. And now it’s coming out in the United States published by Simon & Schuster with a new cover and a new title: The Girl Giant.

Kristen den Hartog’s novel And Me Among Them was one of my favourite books of last year, and my admiration for its author was only intensified when I met her in November for an interview. It’s a quiet book but, like its protagonist, And Me Among Them has made an impact on the world– it was shortlisted for the 2012 Trillium Book Award, and was just awarded the Alberta Trade Fiction Book of the Year Award. And now it’s coming out in the United States published by Simon & Schuster with a new cover and a new title: The Girl Giant.

I met up with Kristen recently and she gave me a copy of the new book. It’s small and square and lovely, but I’ve already got my gorgeous edition from Freehand Books, so I’d like to pass on The Girl Giant to one of you. If you leave a comment below before the end of Sunday June 24 (my birthday!), your name will be entered in a draw and I’ll send the copy of the winner. Good luck, and thanks to Kristen, with congratulations too for all her book’s success.

Update: Congratulations to Deborah! I will be in touch.