August 7, 2012

Above All Things by Tanis Rideout

Ever since I started thinking about these things, the question has occurred to me: what is this literary reflex triggered by books so far away from here and now that convince us that said books are great? Even though some of our best writers write books with titles like Small Ceremonies and or depict parents picking nits from each others’ heads, why are Canadian readers (and awards juries) so swept away by sweeping, by largeness, by grandeur?

Ever since I started thinking about these things, the question has occurred to me: what is this literary reflex triggered by books so far away from here and now that convince us that said books are great? Even though some of our best writers write books with titles like Small Ceremonies and or depict parents picking nits from each others’ heads, why are Canadian readers (and awards juries) so swept away by sweeping, by largeness, by grandeur?

And it doesn’t come any bigger than the the Mount Everest in Tanis Rideout’s first novel Above All Things. The second-biggest topic she tackles is the British Empire and its crumbling. There is a mention of Toronto in the novel, guaranteed to get us all a little giddy, but then George Mallory really doesn’t think much of the place: “Cold. Even after Everest. And grey and dark. The cold there pinned up down.”

That Rideout’s book and its inevitable acclaim will serve as fodder for brand new versions of the “Is Canadian writing un-Canadian?” argument, however, should not undermine the fact that the novel is actually quite extraordinary, really wonderful. Smartly designed with an arts and crafts font, a cover image meant for mass-appeal, marketed as “The Paris Wife meets Into Thin Air“, but yet there is a singularity to this novel. As I read it, I kept thinking, “If every book was as good as this, maybe publishing wouldn’t be in trouble after all.” It’s an ambitious task she takes on, what with empires and mountains, but Tanis Rideout pulls it off, takes the summit. I’ve been disappointed by so many novels lately whose mechanics have been evident beneath their surfaces, whose writer’s stretching has been all too clear, but Above All Things is so perfectly formed, not only a novel to get lost in but one whose literary-ness will surely take you higher.

Above All Things comprises the parallel stories of Ruth Mallory, and her husband George, the latter the mountaineer whose infamous ill-fated Everest attempt makes the novel’s outcome clear from the start. There are several links to Virginia Woolf– the novel’s opening chapter is titled “The Voyage Out”; Woolf herself appears as a character in the book, a contemporary of the Mallorys, well-known thanks to George’s Bloomsbury connections; and Ruth’s own story is told in a Mrs. Dalloway fashion, the hours in the day of a woman with a party to plan, who will buy the flowers herself.

Though it’s not a party she wants to have, necessarily, but she’s having it anyway to put a brave face to the world, to attempt to distract herself from her husband’s absence. It’s his second Everest attempt, though he’d promised he wouldn’t try it again. There is also the time he spent on tour in America, and the years he spent away at war, and so Ruth is accustomed to his absence, but it doesn’t make it easier. It doesn’t make her less resentful either, or less angry, as she meditates on all he’s chosen over her again and again, what it is to come second to a mountain.

Meanwhile George’s own story is told in alternating chapters, taking place over months where Ruth’s is in a single day. His pace furious, the stakes high, and he’s able to avoid meditation for the most part. Rideout goes into considerable detail about the practicalities of an Everest climb in 1924, the minutiae necessary to complete the task, and we begin to see that the boundaries between domestic and wild, between men’s stories and women’s, are not as solid as they seem. George’s single-mindedness means another point of view is required to complete his sections, and Rideout uses that of Sandy Irvine, a young climber only too eager to follow in George Mallory’s footsteps.

Above All Things is a love story, and also a puzzle– is it Mallory’s love for Everest or the love of his marriage that the title refers to? What is a love story whose trajectory is two people moving further and further apart? Rideout writes of her inspiration from the real life letters that George and Ruth wrote to one another, and of how she used the letters as a jumping-off point to change these historical characters to fictional people. She subverts notions of marriage to show it as a many-textured thing, rife with compromise and betrayals upon which love itself doesn’t necessarily hinge. The story also has contemporary resonance in our time in which men are still being urged towards a “duty” that involves dying for their country, in which we’re still learning how to be in a world whose corners are nearly all explored.

So what does it mean then, that I’ve been swept away again? Impressed that this Canadian writer has imagined her way into these historical lives, imagined her way to the top of the world? I’m getting savvier though, and I can tell you this: sometimes the same old arguments have nothing to do with the matter, and I also know a really good book when I see it.

August 6, 2012

The water was warm & the reading was good.

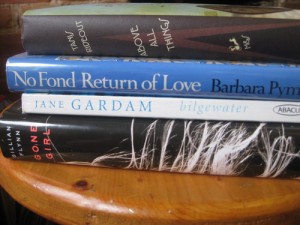

When I tell you that my vacation was wonderful, what I really mean is that I got a lot of reading done. Five novels, kind of six. I started with Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, which was gripping and fun, the perfect beach read for a woman with a brain. The story of a man whose wife has disappeared but then we begin to see that he might have unabashedly been the one who disappeared her. It wasn’t a perfect crime novel– there were so many twists that I felt like I was chasing my tail– but I enjoyed it thoroughly. Next up was Bilgewater by Jane Gardam, which was a wonderful novel. I’d only read Gardam’s Old Filth before, and I’d found it weird, but now within the context of another of her books, I see that it was actually Gardam-esque. Bilgewater is the coming-0f-age story of a girl who has grown up without a mother, living with her eccentric father at a boy’s school, and must navigate her place in the world outside of that context. It would appeal to those who loved Jo Walton’s Among Others, minus the fantasy. Gardham absolutely trusts her reader and her text to light the way through the story, with no interference on the author’s part. She also so vividly illuminates such odd corners of Englishness, ones you never even imagined existed.

When I tell you that my vacation was wonderful, what I really mean is that I got a lot of reading done. Five novels, kind of six. I started with Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, which was gripping and fun, the perfect beach read for a woman with a brain. The story of a man whose wife has disappeared but then we begin to see that he might have unabashedly been the one who disappeared her. It wasn’t a perfect crime novel– there were so many twists that I felt like I was chasing my tail– but I enjoyed it thoroughly. Next up was Bilgewater by Jane Gardam, which was a wonderful novel. I’d only read Gardam’s Old Filth before, and I’d found it weird, but now within the context of another of her books, I see that it was actually Gardam-esque. Bilgewater is the coming-0f-age story of a girl who has grown up without a mother, living with her eccentric father at a boy’s school, and must navigate her place in the world outside of that context. It would appeal to those who loved Jo Walton’s Among Others, minus the fantasy. Gardham absolutely trusts her reader and her text to light the way through the story, with no interference on the author’s part. She also so vividly illuminates such odd corners of Englishness, ones you never even imagined existed.

I remained Anglo-centric with a rereading of Barbara Pym’s No Fond Return of Love, which is my favourite Pym and my first Pym reread since I finished the lot of them last year. I’m entranced by the novel’s meta-narrative, that Pym herself makes an appearence in a hotel dining room and one of her books is referenced as being on a character’s shelf (Some Tame Gazelle). There is much comparison to how life and fiction measure up, a statement that some people could walk onto the pages of a book and you’d never believe they were true. I also know more about Pym’s biography than I did first read, and see this book in connection to her own obsessive, usually unrequited love experiences, which were pretty much the story of my own (love) life for a substantial period. These aren’t stories that are put down in books so often, stalker-ish tendencies well-shy of bunny boiling. Pym is Austenish, certainly, but the solutions to the romantic problems she poses are less conventional than you’d think. She is a strange kind of mathematics that you’ve got to get a feel for to appreciate.

Next up was Tanis Rideout’s Above All Things, a Canadian novel but just as Anglo as the other two in subject matter. It’s very good and though it was a vacation book rather than a book for review, I’ve got much to say about it and will be posting a review this week. Felt just right to be reading it though as last year at the cottage, I read a biography of Gertrude Bell.

We made our annual trek to Bob Burns’ Books in Fenelon Falls on Monday while it rained, and I was so thrilled to find Barbara Pym’s unfinished novel Civil to Strangers. It’s almost impossible to find Barbara Pym books secondhand, so this was a find. I’m saving it for the future so I can continue to have unread Pym before me. I also was happy to find the book Fairy Tale by Alice Thomas Ellis, whose novel The 27th Kingdom blew my mind last year. I didn’t love this one as much, though the more I think about it, the more it gets under my skin. It’s a fairy tale quite literally, but also an English novel of manners. A young woman escapes to the Welsh countryside in search of a simpler life, and finds her general boredom relieved when she comes into possession of a changeling, tragic and rather hilarious results ensuing. Would appeal to anyone who admires Hilary Mantel’s supernatural stuff.

The sixth book was The Hunger Games, whose trilogy had kept Stuart as glued to the page all week as I am to books in general. I was happy to have a chance to read it as when we are at home, I have so many books to read that I don’t have the space for books like it. Predictably and disappointingly, however, I wasn’t very interested in it, and mainly skimmed the last two thirds. I kept comparing it to Bilgewater, which is a book about a similarly aged character and so much more interesting in terms of how it’s written. I found The Hunger Games so predictable, with a protagonist who we’re always meant to be on board with, who is obviously always going to win, and I was frustrated by how everything in the book required so much explanation, by how Katniss Everdeen is writing down to us. It’s sort of patronizing. I also don’t understand the YA preoccupation with post-apocalyptic worlds, how discussion of these books with young people is always meant to be issues based rather than about the book itself. It’s so prescribed. So there you go. I didn’t like the book so much, though I know I was approaching it wrong, I am not its intended audience, and I think I’d been spoiled by having read books all week long which were so brilliant.

Anyway, it was a fantastic week. We swam every day, played on the beach, I sat down so much it made my tailbone ache, loved hanging out with Stuart on the porch and playing games every evening, the weather was glorious, and Harriet was thrilled by not having to wear shoes for a week and running wild with a huge pack of kids to play with. It was perfect. We are lucky. And now we are also happy to be home.

July 26, 2012

Gone Fishing

Well, not really. Fishing is kind of barbaric actually, but plans for the week do include lots of reading with a lakeview. And I’ve got great books packed. In fact, books are all I’ve got packed. So I need to get my act together, but yes. It’s going to be an excellent holiday.

Well, not really. Fishing is kind of barbaric actually, but plans for the week do include lots of reading with a lakeview. And I’ve got great books packed. In fact, books are all I’ve got packed. So I need to get my act together, but yes. It’s going to be an excellent holiday.

July 25, 2012

Afternoon Tea: A Timeless Tradition by Muriel Moffat

No surprise, really, that I’d find this little book appealing, Afternoon Tea: A Timeless Tradition by Muriel Moffat. I am the kind of person who has a tea books shelf in her kitchen (just above the tea things shelf, if you’re wondering). Moffat’s book is an ode to afternoon tea in general, and to tea at Victoria’s Fairmont Empress Hotel in the specific. She writes of her own connections to teatime, of the importance of English grandmothers in passing along such traditions. Her prose is light and punctuated mainly by exclamation marks. She addresses the history of tea and tea ceremonies, a guide to tea-taking (from how to warm the pot to what to wear), and then a chapter on tea at the Empress Hotel, the experience and its history. The rest of the book comprises recipes for scones, cookies, tiny sandwiches and other things (and now I see, I have to get myself a crumpet ring).

No surprise, really, that I’d find this little book appealing, Afternoon Tea: A Timeless Tradition by Muriel Moffat. I am the kind of person who has a tea books shelf in her kitchen (just above the tea things shelf, if you’re wondering). Moffat’s book is an ode to afternoon tea in general, and to tea at Victoria’s Fairmont Empress Hotel in the specific. She writes of her own connections to teatime, of the importance of English grandmothers in passing along such traditions. Her prose is light and punctuated mainly by exclamation marks. She addresses the history of tea and tea ceremonies, a guide to tea-taking (from how to warm the pot to what to wear), and then a chapter on tea at the Empress Hotel, the experience and its history. The rest of the book comprises recipes for scones, cookies, tiny sandwiches and other things (and now I see, I have to get myself a crumpet ring).

As tea books go, Afternoon Tea is hardly groundbreaking, but it’s a pretty little object and a perfect keepsake. Originally self-published with 30,000 copies sold at the Empress Hotel gift shop in five years, it’s now been gorgeously re-packaged by Douglas&McIntyre, and is about to find a wider readership among afternoon tea devotees.

July 25, 2012

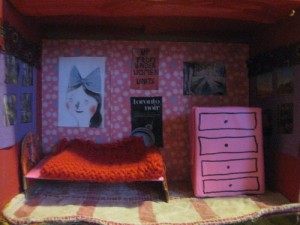

Our shoebox dollhouse

Stuart has taken up running, which is exciting, and means that he bought a new pair of shoes. Also that Harriet was crabby on Saturday while Stuart was out for his run and I was making dinner, and so I distracted her by proposing that we build a shoebox dollhouse. And naturally, the first step was to consult the internet. We found these instructions, and got to work, painting the walls, selecting the wallpaper (which was origami paper). As with every physical object I’ve ever created (except for Harriet), the result is a little bit sloppy. I think the creator of the prototype was a perfectionist, while I am a half-ass-est, and they also didn’t use old kitchen rags for flooring. I don’t think I’m going to be sewing tiny throw cushions either or a bedskirt, but I’m still quite thrilled with the result and Harriet is forbidden to colour on it or put stickers on it. (I am absolutely no fun). I did knit a tiny bedspread (and incidentally, we’ve taken to referring to bedspreads as counterpanes ever since we learned what a counterpane was). We still want to make a few more things– a bookshelf, a clock. Note the lace curtains, and the cool posters in the bedroom. Anyway, Harriet has enjoyed playing with it, even while restricted from sticker putting-onning. And I’m just a little bit in love with the dollhouse too.

Stuart has taken up running, which is exciting, and means that he bought a new pair of shoes. Also that Harriet was crabby on Saturday while Stuart was out for his run and I was making dinner, and so I distracted her by proposing that we build a shoebox dollhouse. And naturally, the first step was to consult the internet. We found these instructions, and got to work, painting the walls, selecting the wallpaper (which was origami paper). As with every physical object I’ve ever created (except for Harriet), the result is a little bit sloppy. I think the creator of the prototype was a perfectionist, while I am a half-ass-est, and they also didn’t use old kitchen rags for flooring. I don’t think I’m going to be sewing tiny throw cushions either or a bedskirt, but I’m still quite thrilled with the result and Harriet is forbidden to colour on it or put stickers on it. (I am absolutely no fun). I did knit a tiny bedspread (and incidentally, we’ve taken to referring to bedspreads as counterpanes ever since we learned what a counterpane was). We still want to make a few more things– a bookshelf, a clock. Note the lace curtains, and the cool posters in the bedroom. Anyway, Harriet has enjoyed playing with it, even while restricted from sticker putting-onning. And I’m just a little bit in love with the dollhouse too.

July 24, 2012

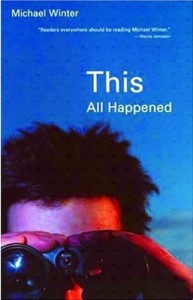

The Vicious Circle reads This All Happened by Michael Winter

Oooh, summer nights with the Vicious Circle are the very best. Last evening, we assembled on one of our favourite West End porches as the night fell, trains rumbled by, lightning flashed, and a storm threatened to arrive. It never did. We ate ice cream sandwiches and delighted in our ever-excellent conversation.

Oooh, summer nights with the Vicious Circle are the very best. Last evening, we assembled on one of our favourite West End porches as the night fell, trains rumbled by, lightning flashed, and a storm threatened to arrive. It never did. We ate ice cream sandwiches and delighted in our ever-excellent conversation.

And speaking of ever, we were once again a book club divided, this time on Michael Winter’s 2000 novel This All Happened. Apparently Gabriel English is meant to be a heartthrob, one of us pointed out, but another disagreed, remembering the Gabriel English from Winter’s previous story collection One Last Good Look. She said, “That Gabriel English is better than this.”

Half of us liked the book, the vignettes, an entry a day for a year about ordinary life. Others found it boring, weren’t pressed to care about anything that happened. (“What all happened?”) And all of us were weirded out by punctuation, the inconsistencies less than the strange choices. No one could give an explanation for the near-omission of apostrophes. One of us pointed out that it was strange that the punctuation was so experimental when the rest of the book decidedly… wasn’t.

But no, we disagreed from the other side of the table, the other side of the bowl of Magnum ice cream bars. It was experimental in particular in relation to his other books, that it was a character from a previous book who was writing a book that Winter himself would actually go on to publish. And it is experimental to write a novel composed of mundanities. A novel in which nothing happens.

The people in this book are annoying, we complained, the main character in particular. We liked the peripheral characters best. We liked Boyd Coady. We weren’t sure what the drippy Gabriel saw in Lydia though perhaps her problem was that we only ever saw her from his point of view. Aspects of her personality seemed contradictory, but then maybe it was just his failure to see her properly.

We remarked upon absurd details going by unremarked upon admist the mundanities, like Max who pokes a hole in a condom to get his girlfriend pregnant. The rest of us realize how awful it is that we hadn’t really considered how awful that was. That Max and Daphne are held up as the great example of love in this book, which is kind of horrifying to consider.

The one moment that gripped us all was the canoe trip, when the pregnant Daphne is thrown out of the boat. This event stands out so much from the rest of the novel. We note that Gabriel English is so passive, that he has these ideals of how things should be and seems content to live on these instead of reality. That nobody has a job in this book– the arts council grants seem very generous. We loved the names, that Craig Regular was never just called by his first name. And Maisie Pye! How remarkable in CanLit that a character with the name of Pye should be good and like-able. We thought about how immature these characters were, what it meant that Gabriel English had lived a whole life until this book begins and yet this sorry love is his most significant.

“Any resemblance to people living or dead is intentional and encouraged…” Winter tells us before his story begins, and we do spend time trying to map his fictions onto reality. The edges don’t quite line-up exactly, however, which is frustrating, interesting, and fascinating. We wonder if this novel of true stories is actually more interesting in theory than execution. Though it definitely succeeds in creating a sense of place, of community. Of arts communities in small towns (and we laugh about the scene in which the erotic poetry reading upstairs from the curling club is broadcast into the curling club by mistake). It’s a novel about ways of seeing, someone remarks, notions of cameras, film, Gabriel’s window which he refers to as the eyes of the city. How the ruggedness of Newfoundland creeps into this novel about a city, in the seasons, how the women are as game to the outdoors as the men are, the fish, the fish.

We think about autobiographical novels, which there is a recent trend for. It makes us think of the reader as being in a position of the only sober person at a table full of drunks. But yes, we think. This novel was intriguing enough. It left us with questions, and that is something.

July 22, 2012

Why You Can Never Have Too Many Mother Gooses

When Harriet was very small, I read a prescription by Mem Fox, the mother of children’s literacy, that we were to give our children ” at least three stories and five nursery rhymes a day, if not more, and not only at bedtime, either.” And while we were doing just fine in the story department, I realized I really had to pick up the pace in terms of nursery rhymes. As much as nursery rhymes were nonsense, they were also so important to developing literacy skills, in their rhythm and rhyme, and I loved how they connected us back to stories that have been told to children for centuries.

When Harriet was very small, I read a prescription by Mem Fox, the mother of children’s literacy, that we were to give our children ” at least three stories and five nursery rhymes a day, if not more, and not only at bedtime, either.” And while we were doing just fine in the story department, I realized I really had to pick up the pace in terms of nursery rhymes. As much as nursery rhymes were nonsense, they were also so important to developing literacy skills, in their rhythm and rhyme, and I loved how they connected us back to stories that have been told to children for centuries.

It was around this same time that Mother Goose collections began entering our lives, right when we needed them most. When Harriet was born, my friend Kate had sent us Scott Gustafson’s gorgeously illustrated Favourite Nursery Rhymes from Mother Goose. Not long after, our next door neighbours gave us their old copy of Iona Opie and Rosemary Wells’ My Very First Mother Goose (with characters, we’d realize later, who were Max and Ruby’s forebunnies).

It was around this same time that Mother Goose collections began entering our lives, right when we needed them most. When Harriet was born, my friend Kate had sent us Scott Gustafson’s gorgeously illustrated Favourite Nursery Rhymes from Mother Goose. Not long after, our next door neighbours gave us their old copy of Iona Opie and Rosemary Wells’ My Very First Mother Goose (with characters, we’d realize later, who were Max and Ruby’s forebunnies).

And so we were chugging along with a Mother Goose in the bedroom and a Mother Goose in the living room, which we thought was probably enough Mother Gooses for one small apartment (with Barbara Reid’s board book Sing a Song of Mother Goose tucked in my purse for days out), until our friends Curtis and Laura gave us Richard Scarry’s Best Mother Goose Ever. Excessive, I know, but we kept this copy in the bedroom too, and we loved Scarry’s cats and rabbits, and his collection’s deliciously violent edge.

And so we were chugging along with a Mother Goose in the bedroom and a Mother Goose in the living room, which we thought was probably enough Mother Gooses for one small apartment (with Barbara Reid’s board book Sing a Song of Mother Goose tucked in my purse for days out), until our friends Curtis and Laura gave us Richard Scarry’s Best Mother Goose Ever. Excessive, I know, but we kept this copy in the bedroom too, and we loved Scarry’s cats and rabbits, and his collection’s deliciously violent edge.

We picked up a copy of Nursery Rhyme Comics last year, because it was the coolest book we’d ever laid eyes on, and here were all of our favourite rhymes made anew by some of the best comic artists working today. The old woman who lives in the shoe heads a rock band, for example, and it’s the Grand Old Duke of York as imagined by Kate Beaton. We love this book, which isn’t as well thumbed through as all the others because it lives up on the shelf for special (which is often).

We picked up a copy of Nursery Rhyme Comics last year, because it was the coolest book we’d ever laid eyes on, and here were all of our favourite rhymes made anew by some of the best comic artists working today. The old woman who lives in the shoe heads a rock band, for example, and it’s the Grand Old Duke of York as imagined by Kate Beaton. We love this book, which isn’t as well thumbed through as all the others because it lives up on the shelf for special (which is often).

And so you might suppose that receiving a second-hand copy of The Arnold Lobel Book of Mother Goose last month would have tipped us into too much Mother Goose, finally, but I don’t think so. We’ve chosen to keep this one in the living room, in case you’re wondering, right next to Iona Opie, and I’ve realized that in our excessive Mother Gooses, my entire parenting philosophy is inherent, the things I want to impart to my daughter most.

And so you might suppose that receiving a second-hand copy of The Arnold Lobel Book of Mother Goose last month would have tipped us into too much Mother Goose, finally, but I don’t think so. We’ve chosen to keep this one in the living room, in case you’re wondering, right next to Iona Opie, and I’ve realized that in our excessive Mother Gooses, my entire parenting philosophy is inherent, the things I want to impart to my daughter most.

First, in that one can never have too many books. Second, that there are many, many versions of the same old story, different words entirely to tell it. Sometimes it’s hickory dickory, and sometimes it’s dickory dickory, is what I mean, and you are even free to make it your own. Third, that we are indeed connected to people who lived hundreds of years ago and told these same stories that we do, and some of them might have even made sense then. That we belong to something larger then ourselves. And then finally, as each of these collections is marvellously illustrated, that the same picture never looks the same to anyone. How different, valid and vivid is each of our separate points of view. That all of our favourite stories and characters are imagined over and over again, and we have to be open minded enough both to respect that, and also to recognize them when they appear.

July 19, 2012

Threading the Light: Explorations in Loss and Poetry by Lorri Neilsen Glenn

“The essay wants to go its own way. In an unstable world, we want to know what we’re getting, and with an essay, we can never be sure. Partaking of the story, the poem, and the philosophical investigation in equal measure, the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go. Places we may not want to go. We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave. That’s the risk we take when we pick up an essay.” –Susan Olding, The Trying Genre

“The essay wants to go its own way. In an unstable world, we want to know what we’re getting, and with an essay, we can never be sure. Partaking of the story, the poem, and the philosophical investigation in equal measure, the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go. Places we may not want to go. We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave. That’s the risk we take when we pick up an essay.” –Susan Olding, The Trying Genre

In Lorri Neilsen Glenn’s essay collection Threading Light: Explorations in Loss and Poetry, we’re given a sense of what we’re getting with its first sentence, “This parcel of essay and verse and anecdote…”, and I love parcels. But it’s true that the reader embarks on the book with just just a vague idea of the parcel’s contents, unsure of where the sentences will lead. The title doesn’t help much either–my husband spotted the cover the other night, and was concerned a book exploring loss and poetry might send me melancholic (and as he has to live with me, he has a right to be concerned).

But it’s not like that at all; light is the word. The book takes its title from the painting by Mark Tobey which, Neilsen Glenn tells us, inspired John Cage to understand that “[w]hen we pay attention to anything–a bird wing, a man sleeping on an open grate, the horizon–it becomes a magnificent world worthy of your attention.” In her bookish parcel, Neilsen Glenn pays attention, digs to the foundations of her preoccupations, and most of these surround instances of loss, the irresolvable– a boyfriend’s suicide, her son’s disability, her mother’s death, the death of a friend, others’ losses, the crash of Swissair Flight 111 not far from her home ( a sound she thought was thunder). Compassion, late blooming (arm-in-arm with motherhood), war and sons, the domestic (“Whatever our differences, there is still laundry”), decades flying by, community and retreating, the art of losing, the gaps in women’s history, encounters with cultural others, on writing communities and the generosity and respect necessary for such communities to thrive. She is drawn to cemeteries, the graveyard in Halifax where the Titanic’s victims are buried, Margaret Lawrence’s grave. The shadows, of course, which come with the light. “The dead carry knowledge that the living cannot. It is we, here, now, who are in the dark.”

The book is the story of Neilsen Glenn’s own progress toward spirituality and poetry. Her narrative is circuitous, undulating, and if I traced it with a pencil, it would end up looking like the Mark Tobey painting. Which means that I’m having as much difficulty as the subtitle is in describing to you precisely what this book is, but I will tell you that the experience of reading it was was a pleasure. That it joins my list of amazing essay collections by Canadian women, books which I might line-up side-by-side and point to when I tell you, “Here’s my personal philosophy. Here’s what it’s all about.”

July 18, 2012

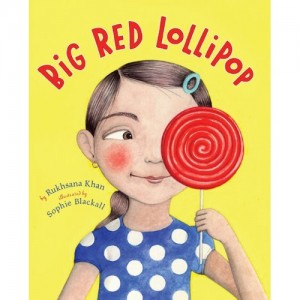

Our Best Book of the Library Haul: Big Red Lollipop by Rukhsana Khan and Sophie Blackall

Big Red Lollipop by Rukhsana Khan and Sophie Blackall is the story of a young girl who is eager to fit at school, but who must also conform to her mother’s cultural expectations. When Rubina is invited to a birthday party, her mother sees no reason why her younger sister Sana can’t go too, even though Rubina protests that everyone will think it’s strange her sister comes. And she’s right, they do. When a while later, Sana is invited to a birthday party of her own and is expected to take along their smallest sister, Rubina overcomes the temptation for revenge and steps in to set their mother right

Big Red Lollipop by Rukhsana Khan and Sophie Blackall is the story of a young girl who is eager to fit at school, but who must also conform to her mother’s cultural expectations. When Rubina is invited to a birthday party, her mother sees no reason why her younger sister Sana can’t go too, even though Rubina protests that everyone will think it’s strange her sister comes. And she’s right, they do. When a while later, Sana is invited to a birthday party of her own and is expected to take along their smallest sister, Rubina overcomes the temptation for revenge and steps in to set their mother right

I’ve read this book five times today, at Harriet’s request, and I’m not sure what draws her to it exactly– she’s a bit too young to get it, and I think she’s mostly entranced by the idea of lollipops. And perhaps there is some attraction to the power struggles between the sisters in the book, the squabbling over sharing that she engages in herself with her own friends. I think both of us are also in love with Sophie Blackall’s illustrations, and the fact that two spreads are maps on which we trace our fingers to follow Rubina’s walk home from school, and the sisters’ dash around the furniture.

Big Red Lollipop defies picture book convention in so many ways. Significant time passes in this book, a good year or so. There are clear instances of injustice taking place in the text, no matter how petty, and it’s frustrating to encounter this as a reader. The characters are of an Asian-immigrant background, but the background is not the point of the story. Here is a book in which an Asian-Canadian child can see herself reflected, and in which my daughter can see people who look different than she is–a reflection of the community we live in. In which the parent is both honoured, but also shown as a person who can learn from her children. It is a picture book with the depth of a novel.