August 22, 2012

The Vicious Circle forgives us our trespasses

Last Thursday, our book club hit what was either an all time low or an all time high, depending on your point of view. If you think it was the former, we will assure you that it wasn’t our fault, but that we’d elected to barely discuss the book at all (a rare act of defiance for the Vicious Circle, which is constitutionally obliged to discuss the book in question at least half as much as it discusses Russell Smith at every meeting) simply because the book was unremarkable. Not in the same way that Wayne Johnston’s Human Amusement was unremarkable, so bizarrely unremarkable that it blew one’s mind with its sheer uninterestingness; how could any book be so thoroughly boring (though to be fair, she of us who writes the blog post recaps felt this most among us, hence the lack of a blog post recap)?

Last Thursday, our book club hit what was either an all time low or an all time high, depending on your point of view. If you think it was the former, we will assure you that it wasn’t our fault, but that we’d elected to barely discuss the book at all (a rare act of defiance for the Vicious Circle, which is constitutionally obliged to discuss the book in question at least half as much as it discusses Russell Smith at every meeting) simply because the book was unremarkable. Not in the same way that Wayne Johnston’s Human Amusement was unremarkable, so bizarrely unremarkable that it blew one’s mind with its sheer uninterestingness; how could any book be so thoroughly boring (though to be fair, she of us who writes the blog post recaps felt this most among us, hence the lack of a blog post recap)?

No, instead the book (which was Trespass by Rose Tremain, her follow-up to the Orange Prize-winning The Road Home [which is a book, it has been reported, that gives Orange Prizes a bad name]) was mind-dumbingly uninteresting. We’ve had a conversation many times inside the Vicious Circle in which one of us makes disparaging remarks about the awfulness of genre-fiction–that it’s not the genre, but the awfulness that troubles. And another of us always points out that literary fiction also has its fair share of crappy books, books that exist solely to meet the lit-fic formula, to win orange prizes, and which actually have no souls of their own. And here was one.

Trespass was stupid, those of us who’d finished shrugged and said it was all right, but that her characters weren’t really people, that elements of the text were preposterous, that we couldn’t understand how it had received that terrific review in The Observer. And then, really, there was nothing more to say, so we moved on to ol’ Russell, debating Caitlin Moran and saying goodbye to one of our own who is decamping to Mexico in the coming days! Though we were saying goodbye via cake, which helped. And it was weird, because we’ve been a book club for almost 2.5 years and the time has flown by, and we’ve had the perfect dynamic, diversity, connection between our members. So we are very sad to see one of us (and she assures us that it wasn’t Human Amusements and Trespass that drove her to it).

We also decided that we had had enough of mediocre books and that maybe we’d all been a little too enthusiastic and uncritical when we planned our next two years of reading about a year ago. So we threw out the list and started anew. No more middling CanLit, no more books chosen because they’d been sitting on our shelves for years and a book club pick would make us pick it up finally. We decided to be more deliberate in our choices, to pick books that are either mostly likely good or that will foster good conversation.

So that we don’t have any more book-free conversations at our meetings in the future. Not that we mind so much when we do. Because even with Trespass and also without it, ours was a very splendid evenings.

August 20, 2012

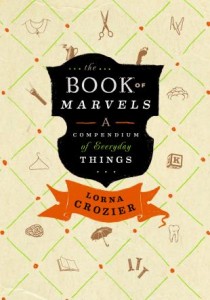

The Book of Marvels by Lorna Crozier

The most disappointing book I ever received was a book of household tips containing such wisdom as how to clean decanters and select bathroom soaps, and poet Lorna Crozier’s new book The Book of Marvels: A Compendium of Everday Things is that disappointing book’s most polar opposite. Fitting for a book that renders ordinary objects extraordinary, Crozier’s book itself is an extraordinary object, one of the few books I’ve ever encountered that dazzles you when its dust jacket falls off: the book is argyle. Its design is splendid, and the contents will not disappoint, guaranteed to appeal to anyone who loves words, and stories, and the thingy-ness of things.

The most disappointing book I ever received was a book of household tips containing such wisdom as how to clean decanters and select bathroom soaps, and poet Lorna Crozier’s new book The Book of Marvels: A Compendium of Everday Things is that disappointing book’s most polar opposite. Fitting for a book that renders ordinary objects extraordinary, Crozier’s book itself is an extraordinary object, one of the few books I’ve ever encountered that dazzles you when its dust jacket falls off: the book is argyle. Its design is splendid, and the contents will not disappoint, guaranteed to appeal to anyone who loves words, and stories, and the thingy-ness of things.

Arranged in alphabetical order, The Book of Marvels is a dictionary of sorts, each definition illuminating the extraordinary lives of objects that we rarely look at twice. Sometimes Crozier will regard a familiar object from an unusual point of view (“Bed: Solid. Immovable. It does little more than take up space in the room it gives its name to, but at night the bed could be any kind of boat…”), use it to tell a story (“The shoe the old dog dropped on the step at dusk… It’s a man’s shoe, black, with a built up sole, as if the owner is a 1950s’ child of polio. Perhaps he’s not lame, just short, and the partner of this show is also heightened…”), invent mythologies (“The first rake was a hand. The older the better, rachitic fingers permanently bent, a scraping tool of bone and flesh…”),or uncover the hidden life within (“All doorknobs are twins, joined at the centre by a bolt narrow as a pencil, inflexible, unvertabraed. Though they move as one, they never get to see each other. They are like siblings separated at birth by a war, by a wall of stone and razor wire”).

I can tell you that I delighted in reading this book on the bus last week, in being the woman seen reading an argyle book called The Book of Marvels, in nearly falling down every time the bus lurched because I’d let go of the hanging strap in order to frantically underline all the best bits. Sometimes the underlines were because the idea was so right, so perfect: “Flashlight: It feels neglected. Too often it’s merely a case for carrying dead batteries.”Or: “The mop lacks the mystery of the broom. No one thinks of it steering through the stars.”

Or the writing: “Shovel:… You’d swear it is a noun but it’s a verb, in stasis, waiting in the shed for a shift of circumstance or season.” And there is this: “Snail: It sails without sails in the garden, so slow, if it were a ship, there’d be no wind.”

The one I went around reading to everybody on Friday was from Fork: “It’s the only kitchen noun, turned adjective, attached to lightning.”

And oh, how I loved: “Whatever it’s called, its country of origin, in a past life the umbrella must have harmed the wind–the wind, without doubt, plots its undoing.”

The Book of Marvels was the title of Marco Polo’s travel writings, and also those of traveller/adventurer Richard Halliburton, and is a title that would set up high expectations for any book, even without the allusions. Lorna Crozier not only meets these expectations, however, she exceeds them, in her excellent argyle book which affirms with delectable language that the world’s wonders are all around us.

August 19, 2012

How to keep more books

I had a revelation yesterday afternoon: if we had a taller bookshelf, we could keep more books. And as we’ve completely run out of floor/wall space for book storage, this revelation was truly a revolution. I did a search for tall bookshelves on Craigslist and very nearly forgot my recent vow to buy no more furniture that isn’t really furniture (bookshelves with cardboard backs or made of particle board), and then I found a listing for a solid wood bookshelf for only $40. The ad had been up for a week, but I got an immediate response from a seller who’d only just started answering her responses and who’d recognized my name as we had a mutual friend. She also just lived up the street, which was handy, so I took a trip there last night in the Autoshare cargo van, and brought this beauty of a bookshelf home. Of course, its arrival has instigated a massive clear-out/re-organzation that has since turned the entire house to chaos, and resulted in a massive pile of free books being put out on the curb (which were gone in two hours, and yes, my bookish garden is better for the pruning). The task before me now is to clear out our garret-turned-overstuffed-storage-closet, which is totally terrifying. But in the meantime, there is the brand new bookshelf, and we’re absolutely in love with it.

I had a revelation yesterday afternoon: if we had a taller bookshelf, we could keep more books. And as we’ve completely run out of floor/wall space for book storage, this revelation was truly a revolution. I did a search for tall bookshelves on Craigslist and very nearly forgot my recent vow to buy no more furniture that isn’t really furniture (bookshelves with cardboard backs or made of particle board), and then I found a listing for a solid wood bookshelf for only $40. The ad had been up for a week, but I got an immediate response from a seller who’d only just started answering her responses and who’d recognized my name as we had a mutual friend. She also just lived up the street, which was handy, so I took a trip there last night in the Autoshare cargo van, and brought this beauty of a bookshelf home. Of course, its arrival has instigated a massive clear-out/re-organzation that has since turned the entire house to chaos, and resulted in a massive pile of free books being put out on the curb (which were gone in two hours, and yes, my bookish garden is better for the pruning). The task before me now is to clear out our garret-turned-overstuffed-storage-closet, which is totally terrifying. But in the meantime, there is the brand new bookshelf, and we’re absolutely in love with it.

August 16, 2012

Mary Poppins and Afternoon Tea

“So, still admiring themselves and each other, they moved on together through the little wood, till presently they came upon a little open space filled with sunlight. And there on a green table was Afternoon-Tea!

“So, still admiring themselves and each other, they moved on together through the little wood, till presently they came upon a little open space filled with sunlight. And there on a green table was Afternoon-Tea!

A pile of raspberry-jam-cakes as high as Mary Poppins’s waist stood in the centre, and beside it tea was boiling in a big brass urn. Best of all, there were two plates of whelks and two pins to pick them out with.

“Strike me pink!” said Mary Poppins. That was what she always said when she was pleased.

“Golly!” said the Match-Man. And that was his particular phrase.

“Won’t you sit down, Moddom?” enquired a voice, and they turned to find a tall man in a black coat coming out of the wood with a table-napkin over his arm.

Mary Poppins, thoroughly surprised, sat down with a plop upon one of the little green chairs that stood round the table. The Match-Man, staring, collapsed on to another.

“I’m the Waiter, you know!” explained the man in the black coat.

“Oh! But I didn’t see you in the picture,” said Mary Poppins.

“Ah, I was behind the tree,” explained the Waiter.

“Won’t you sit down?” said Mary Poppins, politely.

“Waiters never sit down, Moddom,” said the man, but he seemed pleased at being asked.

“Your whelks, Mister!” he said, pushing a plate of them over to the Match-Man. “And your Pin!” He dusted the pin on his napkin and handed it to the Match-Man.

They began upon the afternoon-tea, and the Waiter stood beside them to see they had everything they needed.

“We’re having them after all,” said Mary Poppins in a loud whisper, as she began on the heap of raspberry-jam-cakes.

“Golly!” agreed the Match-Man, helping himself to two of the largest.

“Tea?” said the Waiter, filling a large cup for each of them from the urn.

They drank it and had two cups more each, and then, for luck, they finished the pile of raspberry-jam-cakes. After that they got up and brushed the crumbs off.

“There is Nothing to Pay,” said the Waiter, before they had time to ask for the bill. “It is a Pleasure. You will find the Merry-go-Round just over there!” And he waved his hand to a little gap in the trees, where Mary Poppins and the Match-Man could see several wooden horses whirling round on a stand.

“That’s funny,” said she. “I don’t remember seeing that in the picture, either.”

“Ah,” said the Match-Man, who hadn’t remembered it himself, “it was in the Background, you see!”

The Merry-go-Round was just slowing down as they approached it. They leapt upon it, Mary Poppins on a black horse and the Match-Man on a grey. And when the music started again and they began to move, they rode all the way to Yarmouth and back, because that was the place they both wanted most to see.

When they returned it was nearly dark and the Waiter was watching for them.

“I’m very sorry, Moddom and Mister,” he said politely, “but we close at Seven. Rules, you know. May I show you the Way Out?”

They nodded as he flourished his table-napkin and walked on in front of them through the wood.

“It’s a wonderful picture you’ve drawn this time, Bert,” said Mary Poppins, putting her hand through the Match-Man’s arm and drawing her cloak about her.

“Well, I did my best, Mary,” said the Match-Man modestly. But you could see he was really very pleased with himself indeed.

Just then the Waiter stopped in front of them, beside a large white doorway that looked as though it were made of thick chalk lines.

“Here you are!” he said. “This is the Way Out.”

“Good-bye, and thank you,” said Mary Poppins, shaking his hand.

“Moddom, good-bye!” said the Waiter, bowing so low that his head knocked against his knees.

He nodded to the Match-Man, who cocked his head on one side and closed one eye at the Waiter, which was his way of bidding him farewell. Then Mary Poppins stepped through the white doorway and the Match-Man followed her.”

-From P.L. Travers’ Mary Poppins, which our whole family has been so enjoying for the past week or so.

August 14, 2012

The Blondes by Emily Schultz

I appreciated Emily M. Keeler’s piece about pre-natal narratives and connections between Emily Schultz’s The Blondes and The Handmaid’s Tale, but it was actually Atwood’s The Robber Bride that The Blondes had me thinking of. Because while The Blondes certainly has a post-apocalyptic feel (as have so many other books this year, books as different as Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Lauren Groff’s Arcadia), fundamentally, The Blondes is a novel about how women betray one another. From the first page: “For women, power comes by subtle degrees. I could write a thesis on such women–and I nearly did.”

I appreciated Emily M. Keeler’s piece about pre-natal narratives and connections between Emily Schultz’s The Blondes and The Handmaid’s Tale, but it was actually Atwood’s The Robber Bride that The Blondes had me thinking of. Because while The Blondes certainly has a post-apocalyptic feel (as have so many other books this year, books as different as Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Lauren Groff’s Arcadia), fundamentally, The Blondes is a novel about how women betray one another. From the first page: “For women, power comes by subtle degrees. I could write a thesis on such women–and I nearly did.”

The narrator is Hazel Hayes, and she is addressing her unborn child, mostly because she has no one else to talk to and nothing else to do. Also because she wants to put the pieces of her story back together, to understand the story for herself. She has been a graduate student in New York City, studying “aesthetology”, the study of looking. Her work has been unfocused, mainly because she’s just run away from an affair with her (married) professor in Toronto, Professor Karl Mann (born Karl Diclicker, and many of Schultz’ name-choices are so delightfully Dickensian– in New York, Hazel’s made her home at the Dunn Inn, Hazel’s own name with its ambiguous colouring and haziness, the woman who she appeals to for saving is called Grace). Things become even more complicated when Hazel discovers that she’s pregnant, and her attempts to get home to deal with the problem are stymied by the effects of a mysterious plague.

The plague is “Blonde Fury”, the media label applied with alacrity, as instances of fair-haired women acting out murderous fits of rage begin to take hold in New York and quickly spread through the world. And this premise was all I really knew about this novel before I read it, imagining the book as some kind of fashionable zombie romp, but I’d got it all wrong. First, because the plague itself is very much of this world, complete with scientific explanations involving melanin and double-X chromosomes. And second, because the plague itself functions just as effectively as metaphor as it does plot-driver, compelling the reader to rush through the pages (and I’ll put it to you like this: this was a 380 page novel that I read in a single weekend when I was out of town) and then to go back to the beginning and re-experience the story again in all its depth.

Just as in her studies (and in her life), Hazel imagines herself to be at a remove from womanhood, she situates herself on the periphery of the plague as well, consumed as she is by her personal problems. However, she is actually a witness to the first known attack, when a blond woman throws a teenage girl onto the subway tracks. When Hazel tries to back to Canada not long after, she’s injured when a pack of flight attendants go on a rampage at the airport. When she later tries to cross the border in a rental car, she’s detained and kept under quarantine, and though she seems to go unaffected by the virus, it’s unknown whether her own hair color actually makes her more susceptible–although Hazel has long dyed her hair an unremarkable brown, her natural colour is red. (“What was orange, but a variation on gold? Red-gold. A thing ablaze.”)

She also displays some of the symptoms of blonde fury herself– panic attacks, feelings of rage, depression. Which isn’t so surprising really, considering how general the symptoms are. “The threat becomes abstract, and the fear is almost as intense as the disease itself.” The public is urged to avoid contact with the apparently afflicted: “The thing about the disease is that it’s based on connection.” And so women turn on women in futile attempts to protect themselves.

But this is nothing new, of course, this idea that women are manipulated in order to undermine their power as a mass. Even before the plague, we see that Hazel’s study of female beauty is personal, that she admits to a fear of beautiful women, that she sees these women as “others”. In her affair with her Professor “Mann”, she has set herself in opposition to his wife. She smiles apologetically to men being harassed by women in the street. When she finds herself pregnant, she admits, “The academic feminist part of me felt defeated: devastated by biology, I had run out to get by hair done as a balm.”

Hazel’s few friendships and alliances with women are shattered as individuals try to navigate their respective ways to safety. When Hazel is put into quarantine, she leaves a friend at the border; she takes advantage of her oldest friend; she leaves vulnerable women stranded so as not to put herself in harm’s way. “Power comes in subtle degrees.” “If you come from very little, why give up privilege?” But Hazel ultimately finds herself entirely powerless to her biological destiny and to patriarchal tyranny when the plague and its circumstances make impossible her choice to terminate her unwanted pregnancy. Schultz shows how change creeps in little by little so that to a feminist academic, lack of access to abortion can become almost remarkable.

The Blondes is powerful and solid, gripping and scary. And if it had a soundtrack, I”ve no doubt that this song would be on it.

August 13, 2012

The Beautiful Mystery by Louise Penny

Louise Penny’s latest Chief Inspector Gamache novel The Beautiful Mystery was a present I gave myself, the nicest way to come down after returning home from a perfect holiday. My second Louise Penny, after A Trick of the Light, but this time far removed from Quebec’s Eastern Townships. When a murder occurs at the remote Saint-Gilbert-Entre-les-Loups monastery, the cloistered monks are forced to break their vow of silence and open their doors to outsiders, because the murder has been committed by one of their own.

Louise Penny’s latest Chief Inspector Gamache novel The Beautiful Mystery was a present I gave myself, the nicest way to come down after returning home from a perfect holiday. My second Louise Penny, after A Trick of the Light, but this time far removed from Quebec’s Eastern Townships. When a murder occurs at the remote Saint-Gilbert-Entre-les-Loups monastery, the cloistered monks are forced to break their vow of silence and open their doors to outsiders, because the murder has been committed by one of their own.

The entire novel takes place over just two days, during which Armand Gamache and Jean-Guy Beauvoir have been stolen away from their domestic arrangements in Montreal to take the case on. The separation is particularly significant for Jean-Guy who has just made solid his relationship with Gamache’s daughter Annie, though they’ve not yet told the world of their plans. Unable to access the internet or get a phone signal at the monastery, Annie and Jean-Guy send missives of love via Blackberry messenger.

It’s a challenge Penny has set for herself, to situate a detective story in such a closed community in such a short period of time. All suspects present and accounted for, all identically clad and, until recently, silent. The challenge is heightened for Gamache and Beauvoir as well–the monks know their own world better than anyone, rarely betray themselves with errant words, and are adept interpreters of the police officers’ own gestures and facial expressions, skills learned from years of silent community. They’re a tough lot to crack.

The Beautiful Mystery of which the book’s title speaks is the effect of the monks’ Gregorian chanting, recordings of which had made their way into the world and made the reclusive order world-famous. In different ways, Gamache and Beauvoir fall under the spell of the chanting as they conduct their investigation. The chants themselves also take on significance as it’s the choir director who has been murdered. Could the chants themselves be key to understanding what stirred one of the monks to murder? And what of the mysterious music notation the choir director had been clutching in his hands when he died?

The investigation is further complicated by the unexpected arrival of Gamache’s superior, who’s determined to cause trouble in Gamache’s relationship with Beauvoir. What are his motives? Will the still vulnerable Beauvoir remain loyal to his boss? Are Gamache’s own motivations as innocent as they seem? In the other-worldly Saint-Gilbert-Entre-les-Loups, it’s hard to tell who is friend or foe.

Penny’s distinctly stilted prose can be’ difficult to warm to, though it flows easily once the reader gets a sense of her rhythm. The novel is peppered with Gamache’s literary allusions and with pop culture references also, which add extra texture to her already substantial story. Its characteristically strong sense of place and connections to current events drive this point home even further, so that yes, as it begs to be said, Louise Penny has crafted another “beautiful mystery” of her own.

August 12, 2012

Long Weekend

No post tonight as Pickle Me This is extending the weekend. We had just a little too much fun at the wedding of Rebecca Rosenblum and Mark Sampson, and three cups of tea and a late afternoon nap have done nothing to ease the post-party burden. So we will take to the bath with a copy of Emily Schultz’ The Blondes, which is so wonderful. And in the meantime, check out the wedding cake– with books on top! A most fitting cake for this literary duo, and my goodness, did they ever throw a party. It was a fantastic event, and only the beginning of a really delightful, inspiring, happy tale they’ll make together. So happy to be a supporting character. So happy for them both. xo

No post tonight as Pickle Me This is extending the weekend. We had just a little too much fun at the wedding of Rebecca Rosenblum and Mark Sampson, and three cups of tea and a late afternoon nap have done nothing to ease the post-party burden. So we will take to the bath with a copy of Emily Schultz’ The Blondes, which is so wonderful. And in the meantime, check out the wedding cake– with books on top! A most fitting cake for this literary duo, and my goodness, did they ever throw a party. It was a fantastic event, and only the beginning of a really delightful, inspiring, happy tale they’ll make together. So happy to be a supporting character. So happy for them both. xo

August 9, 2012

On Inger Ash Wolfe and my career failure as literary sleuth

I thought I’d solved a literary mystery a few weeks back, completely by accident too. It was a Saturday morning and I was sitting at home in my pajamas putting up a new week’s main page at 49thShelf. A new book was out called A Door in the River by the pseudonymous Inger Ash Wolf, and the title seemed familiar to me. I could have sworn it was a song by Crowded House, which was intriguing. (Apparently if you want at least one reader and you want her to be me, you should name your next book Weather With You.) So I googled the title to discover that the Crowded House song I was thinking of was “Hole in the River”, but that was no longer the point once I’d stumbled on this page, a biography of Canadian writer Don Coles on the site “Canadian Poetry Online”.

I thought I’d solved a literary mystery a few weeks back, completely by accident too. It was a Saturday morning and I was sitting at home in my pajamas putting up a new week’s main page at 49thShelf. A new book was out called A Door in the River by the pseudonymous Inger Ash Wolf, and the title seemed familiar to me. I could have sworn it was a song by Crowded House, which was intriguing. (Apparently if you want at least one reader and you want her to be me, you should name your next book Weather With You.) So I googled the title to discover that the Crowded House song I was thinking of was “Hole in the River”, but that was no longer the point once I’d stumbled on this page, a biography of Canadian writer Don Coles on the site “Canadian Poetry Online”.

Inger Ash Wolfe, until more recently than the Saturday morning I’ve been referring to, was the pseudonym of a well-known Canadian literary author, and Door in the River was his/her third Hazel Micallef detective novel. And, as I discovered from the Don Coles biography, “A Door in the River” was also the title of a chapter from an unpublished novel by Don Coles, a chapter that was published in The Tamarack Review in 1964.

A strange coincidence, I figured. What are the odds? Further, Coles and Inger Ash Wolfe share a publisher, which published Coles’ literary novel Doctor Bloom’s Story in 2004. Inger Ash Wolf’s name has its Scandinavian edge, while Coles has spent time living in Denmark and Sweden. And no one else had ever guessed! It was amazing. So obvious, staring us all in the face (as long as we were looking at the Canadian Poetry Online website). I realized that Don Coles was hardly the biggest name in Canadian literary authors, but then all the more reason for the mysterious alter-ego, no? Perhaps Coles had forgotten about the Tamarack Review publication, nearly 50 years ago, when he’d resurrected his long-unpublished novel as a contemporary mystery, and kept the old title. Or maybe it was a clue, that he wanted us to find it. That Don Coles wanted to be found.

Perhaps it was Don Coles himself who’d set me loose that Saturday morning. I got dressed and my family consented to have me leave them, because I was off to solve a literary mystery after all. I am fortunate to have the University of Toronto’s Robarts Library at the end of my street, fortunate to have its opening hours include Saturday mornings in the summer. I was even permitted to enter the stacks, because my part-time instructor status comes with a library card. And so up I went to the 13th floor, which was dark and empty save for two students checking Facebook. When I came to the shelf where The Tamarack Review was stored, the lights switched on above me, almost as though the library knew I was there.

It was even on the shelf, albeit dusty, the issue I needed, from Summer 1964. Don Coles had published as “D.L. Coles”, alongside such notables as Margaret Laurence and George Jonas (and just in case you wondered when I was going to bring all this around to gender, there were two women contributors to eight male). Such a triumph, the book in my hands bringing me one step closer to the mystery’s solution. I was high on the smell of the stacks, bookish redolence I don’t get to experience so much now that I’m out of school. I was imagining that I was Maud Bailey. I wondered if I’d become a little bit famous.

The story itself though didn’t fit so well into the scheme. It was curious that Wolfe’s story of a small down Ontario female police detective had originated with this story of a failed architect in Florence in 1960. Coles’ story was mysterious, surely, full of gaps, but it wasn’t a mystery. I wondered… The key, I decided, would be the door in the river image. In Coles’ story the door is as literal as it is symbolic, a drowned door in a river in Florence, half-submerged, and “around it were squares of masonry and odd chunks of chimney, all that was left of the quartiere vecchio that the tidily retreating Germans had blown into the river with the bridges sixteen years before…”

So you can imagine that I was gutted two weeks ago when Michael Redhill outed himself as Inger Ash Wolfe, completely thwarting my dreams of professional literary sleuthdom. It was doubly frustrating because it was so predictable; Redhill had been suspected of Inger Ash Wolfing for ages. Whereas no one had ever suspected Don Coles, and the 1960s’ Tamarack Review connection. But alas, the answer that would make the best story (written by me, of course) can’t always be the right one.

August 9, 2012

On cracking the code of Canadian literary criticism

When I started paying attention to Canada’s literary conversations about five or six years ago, it was quickly evident that I had a whole lot to learn. Until that point, my reading tastes had been determined by prize lists, by what was front and centre at the bookstore, and what the Globe & Mail saw fit to review. I didn’t know that it wasn’t all right to love In the Skin of a Lion or that The Stone Diaries didn’t set every reader swooning. I had no idea of the vast richness of books being published by Canadian small presses like Goose Lane, Anvil and Biblioasis. I still connected House of Anansi to Yorkville hippies. In short, I didn’t have a clue.

So I started taking notes, trying to pin the whole thing down. There was a code, I was beginning to understand, and if only I could get it right. Books with rural settings were bad, and prairie fiction was a crime, I was starting to see. We wanted our books urban. We especially wanted them to be about young men in their twenties. But then it got confusing because it turned out that the prairies were okay as long as they were written by Robert Kroetsch, and even small town fiction about women’s lives were fine as long as it was written by Alice Munro. It got confusing too because it turned out that urban fiction was bad after all, particularly Toronto’s which wasn’t authentically Canadian.

Whether David Adams Richards was okay depended on your point of view, because while he was ticking all the right boxes, he wasn’t ticking them correctly. Bonnie Burnard’s A Good House was a shorthand for all that was wrong with the world. And it turned out that while small press books were really great, small press books were also terrible, and while it was really wonderful that Gaspereau book had won the Giller, did it have to be that Gaspereau book? And who fucking cares about the Giller anyway? You will disdain the Giller. Until your book ends up on its longlist (and not even by popular vote).

Eventually, it became clear that there was no code after all, and that instead we had a whole lot of critics shouting at each other, discussing work in theory, but with no one actually talking about books. That there are as many points of view regarding Canadian Literature and literature in general as there are books themselves, and that is okay. I disagree, however, that all this shouting/debate has made for a healthier literature, mainly because nobody ever listens in a debate, being too busy planning their rebuttal, and the arguments were rarely about reading after all.

It’s such a narrow way to approach literature, to think of it first in terms of themes and tropes. And it’s even narrower when you don’t bother to read the books in question, dismissing them outright based a sentence or two from a publisher’s catalogue. Or because they happen to be set in the past, or on a prairie, or in Toronto, or in a lighthouse, or because people like them, or because women like them (which is usually the worst crime of all for a book to commit).

It may always be 1955 in CanLit, as some say, but I can’t say our sorry excuse for criticism is much more progressive.