February 27, 2013

The problem with optimism

The problem, of course, with my resilient and cheerful “It’s just a cyst!” response to last week’s lump discovery is that when an ultrasound suggests it’s something more suspicious than that, being optimistic just starts to seem stupid. Which is why I’ve spent many of the last 20 hours crying, imagining myself having the rarest form of thyroid cancer that has no treatment and kills in six months, and why the poor woman who made the mistake of asking how I was this morning was met with me bursting into tears. If you thought I was planning my funeral last week, it’s got nothing on what’s happened since. And baby has been kicking away like a mad-fetus, is healthy as ever, but this isn’t really consoling, actually, because I just keep thinking, “You can’t be here without me.”

And so the fact of the matter is that yesterday’s ultrasound revealed suspicious results and I am being referred to for a biopsy. I am really scared, not of a biopsy or even surgery, but of more bad news that is the opposite of what I’m expecting to hear. I am also nervous because I know that being in the third trimester of pregnancy complicates things, and that I wouldn’t be able to have surgery until after our baby comes. I keep desperately googling various combination of terms in an effort to finally stumble on the site that says, “You, Kerry, are going to be fine,” but I haven’t found that one yet. Even though I know that there is a good chance the lump is benign, and that even if it isn’t, that it can be treated, and that the survival rate for thyroid cancer is 97%, and these are the things I keep trying to remember, but it is hard to stay grounded. I have always had this weird tendency to see worry as insurance too, and fear that being optimistic will only trip things up and make everything fall apart.

I picked up Ina-May’s Guide to Breastfeeding at the library yesterday, and thought, “How on earth am I going to find time to read this book?” And then I heard from my doctor and it all seemed more and more unlikely. How does anyone ever has time for any of this? And how do you bear the waiting, the unknowing, the uncertainty (which is basically what life is, usually we can fool ourselves into thinking it’s less precarious)? What is giving me a little bit of peace though is imagining the summer, our baby here, leaves on the trees, and I do suppose the whole “not being dead” thing is going to give the post-partum days a rather glorious perspective. In the meantime, however, it is hard to just wait.

February 26, 2013

DisPossession by Marlene Goldman

“…the act of rereading–of doubling back and engaging with the spectre–is integral to the process of coming at the self, community, and nation-state creatively. Indeed, the power and attraction of the ghost lie in its transitional status–the fact that it hovers elusively between life and death, past and present, self and other. Ultimately, our encounters with ghosts–whether as terrifying shadows or as benevolent ancestral spirits–signal to us that we have entered the complex territory of home.”

“…the act of rereading–of doubling back and engaging with the spectre–is integral to the process of coming at the self, community, and nation-state creatively. Indeed, the power and attraction of the ghost lie in its transitional status–the fact that it hovers elusively between life and death, past and present, self and other. Ultimately, our encounters with ghosts–whether as terrifying shadows or as benevolent ancestral spirits–signal to us that we have entered the complex territory of home.”

Marlene Goldman’s course “The Politics and Poetics of Haunting in Canadian Literature” was one of my favourite parts of graduate school, and so when I discovered that the course had turned into a book, DisPossession: Haunting in Canadian Fiction, I was excited to read it. Canada is a land without ghosts, so has been declared by writers Catherine Parr Traill and Earle Birney, but Goldman shows that contemporary Canadian fiction is in fact rife with spectres. She politicizes and historicizes the trope of haunting by focussing on a few key texts: The Double Hook by Sheila Watson, The Cure for Death by Lightning by Gail Anderson-Dargatz, John Steffler’s The Afterlife of George Cartwright, Jane Urquhart’s Away, Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood, various works by Dionne Brand, and Thomas King’s Truth and Bright Water.

Goldman shows that in Canadian Gothic fiction (fiction in which the present is thought to have something more sinister and complicated lurking behind it than just the past), ghosts come about due to acts of possession, namely colonial atrocities against Indigenous peoples and land taken from them. (She links this idea with Freud’s definition of the uncanny, of something being both home and also not home.) This is demonstrated also in The Afterlife of George Cartwright, but Goldman takes the further step of noting that laws of primogeniture, which delivered Cartwright and others like him to the “New World”, were also an act of possession, rendering English sons homeless spectres in their own country, and dispossessed. She complicates the reading of Away by showing how its magic-realism sanitizes and romanticizes actual history. In both Away, Alias Grace, and works of Brand, Goldman portrays the female body as a site of possession and that possession as the effect of various trauma–possibly also as an assertion of control in a society in which women were powerless over their bodies and their destinies. And then with Truth and Bright Water, she demonstrates that ghosts exist not only to stir up histories that should not be forgotten, but also to help make sense of the present and offer hope for the future.

DisPossession is unabashedly academic, which represents a challenge for those of us who are common readers, and I would have also appreciated a broader, less specific approach to the nature of ghosts in Canadian literature beyond these texts. But this is only because I am greedy, and because my appreciation and understanding of the books in questions here have so been deepened by Goldman’s treatment. She shows that Canadian literature is more complex and relevant to the world beyond the page than many would have us believe.

February 25, 2013

Eloise Wilkin's The New Baby (or, "The Blog Post That Cost Me $50")

In November of 1981, my sister was born, when I was 2. The month before, according to to the note my mom made on the inside cover, I received from family friends a copy of The New Baby by Ruth and Harold Shane, illustrated by Eloise Wilkin. The New Baby became quite famous in our family as I memorized it entirely, and I’d amaze guests with my precocious “reading” skills. I have quite a vivid recollection of engaging with this book when I was very small, and when I read it now with Harriet, it’s not surprising that I loved it.

In November of 1981, my sister was born, when I was 2. The month before, according to to the note my mom made on the inside cover, I received from family friends a copy of The New Baby by Ruth and Harold Shane, illustrated by Eloise Wilkin. The New Baby became quite famous in our family as I memorized it entirely, and I’d amaze guests with my precocious “reading” skills. I have quite a vivid recollection of engaging with this book when I was very small, and when I read it now with Harriet, it’s not surprising that I loved it.

It’s something about Eloise Wilkin’s illustrations, I think. One of my other favourite childhood books was We Help Mommy, written by Jean Cushman, whose pictures still intrigue me now as much as they did 30 years ago. They intrigue Harriet too. It’s funny, because the illustrations were dated when I was small, and by now they’re probably about 70 years off, but it doesn’t make them any less engaging. Perhaps even more so? Because time has made these simple domestic tales become full of tiny mysteries (ie why do they clean the floor with a dust mop and not a vacuum?). These stories also show how the most essential parts of childhood never change.

Anyway, I wanted to write about The New Baby, which my mom saved for many years and passed along to Harriet not long ago. Harriet is now absolutely obsessed with it too as we await the arrival of our own new baby a few months down the road. I like the book too, but the pictures fascinate me for different reasons, the uber-’70s fashions in particular. Check out the kitchen, with the cookbooks and lentils in jars up on the shelf, and whatever they’re eating out of a tagine. The copper pots! Mom’s billowy dress. On other pages, we encounter dad’s indescribably nasty suit (yellow with a blue and red print) and Aunt Pat’s brilliant red plaid pants and pink collegiate sweater at the end of the book. It turns out some things do change, and thank goodness…

Anyway, I wanted to write about The New Baby, which my mom saved for many years and passed along to Harriet not long ago. Harriet is now absolutely obsessed with it too as we await the arrival of our own new baby a few months down the road. I like the book too, but the pictures fascinate me for different reasons, the uber-’70s fashions in particular. Check out the kitchen, with the cookbooks and lentils in jars up on the shelf, and whatever they’re eating out of a tagine. The copper pots! Mom’s billowy dress. On other pages, we encounter dad’s indescribably nasty suit (yellow with a blue and red print) and Aunt Pat’s brilliant red plaid pants and pink collegiate sweater at the end of the book. It turns out some things do change, and thank goodness…

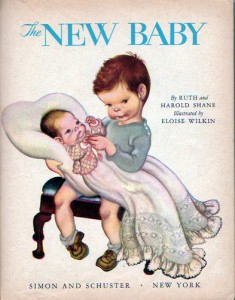

While I was googling to find images of the illustrations, however, I discovered that there was another version of The New Baby by Eloise Wilkin, and Ruth and Harold Shane. Turns out my book was a revised edition published in 1975, with updated illustrations. The original was published in 1948, and Wilkin’s drawings have a more-than-slightly-terrifying Norman Rockwell thing going on. Aunt Pat in this one is a hideous spinster with a crooked back, and in the kitchen there is not a lentil to be found. I was much intrigued by this, and really wanted to find out more about the original version of this book which was basically my literary foundation. It’s not in the library system but I tracked down a copy on AbeBooks, which should be coming my way in the next few weeks. I’m really looking forward to finding out the differences between the two.

While I was googling to find images of the illustrations, however, I discovered that there was another version of The New Baby by Eloise Wilkin, and Ruth and Harold Shane. Turns out my book was a revised edition published in 1975, with updated illustrations. The original was published in 1948, and Wilkin’s drawings have a more-than-slightly-terrifying Norman Rockwell thing going on. Aunt Pat in this one is a hideous spinster with a crooked back, and in the kitchen there is not a lentil to be found. I was much intrigued by this, and really wanted to find out more about the original version of this book which was basically my literary foundation. It’s not in the library system but I tracked down a copy on AbeBooks, which should be coming my way in the next few weeks. I’m really looking forward to finding out the differences between the two.

All this googling also directed me to the book Golden Legacy by Leonard Marcus, about the history of the Golden Books. (Apparently, I wrote about this book five years ago, though children’s books meant less to me then, which was probably why I never followed through so far as to actually read it.) As there is not a circulating copy of this book in the Toronto Public Library system, I was left with no choice but to order a copy for myself, which should arrive sometime this week. Very excited to encounter this one. Deirdre Baker’s 2008 review in the Toronto Star heightens my expectations.

Anyway, all this is how the quest to write this blog post ended up costing me 50 bucks. It’s going to lead to more blog posts though, and to new literary discoveries, and so I’m willing to bet that it all will be worth every penny in the end.

February 24, 2013

"Worse still, her parents were always bringing home MORE books."

The Girl Who Hated Books by Jo Meuris, National Film Board of Canada

Three years ago, I posted about this short film, but I’m returning to it again because this weekend I purchased the book upon which it is based for 50 cents from a bake sale/book sale taking place outside Harriet’s swimming lessons (along with a rice crispie square and two slices of cake). The book is The Girl Who Hated Books by Manjusha Pawagi and Leanne Franson, and we love it. I like the glimpses of storybook characters we know and love, but also how the family in the book is a little bit like our own, only far more eccentric:

“There were books in dressers and drawers and desks, in closets, cupboards and chests. There were books on the sofa and books on the stairs, books crammed in the fireplace and stacked on the chairs.

Worse still, her parents were always bringing home MORE books. They kept buying books and borrowing books and ordering books from catalogues. They read at breakfast and lunch and dinner…”

We’re not quite that bad, and while we do have books crammed in the fireplace, on the stairs, and even on our ceiling, we have not yet had to resort to the sink. And reading at dinner is strictly forbidden, though breakfast and lunch is all right, Saturday paper breakfast in particular. Obviously.

I like this book also because it’s a perfect addition to the excellent list we posted at 49thShelf last week, Picture Books Featuring Canadian Children of Colour, compiled by TPL librarian Joanne Schwartz.

February 21, 2013

Something is not right.

I don’t imagine I touch my neck very often, but somehow yesterday while I was eating breakfast, I happened to discover a very large lump on my throat. “Something is not right,” I realized, in Miss Clavel style, and it was an interesting realization because I spend as much as any woman does examining my body for lumpy things, and being that bodies are quite lumpy in and of themselves, I’d always wondered how you’d know when you found a real one. But it’s like love, I guess, and orgasms. I got up from the table and announced that I had googling to do. I kept googling to a minimum as you always should whenever anything is actually wrong, and made an appointment with my doctor. She saw me later in the afternoon, and couldn’t believe I hadn’t noticed the lump before. But then, as I’ve stated, I don’t touch my neck very often. The lump, she says, is on my thyroid, and feels more like a cyst than a nodule (and therefore, hopefully, less likely to contain nasty things). It is probably huge because I am pregnant, and pregnant bodies don’t do anything half way. She told me I am not to worry. I have an ultrasound next week which will confirm just what the lump contains. It is likely we won’t have to worry about what to do about it until after the baby is born. She said, “You’ve got bigger fish to fry anyway” (ie having a baby, who is, I am grateful to say, bigger than the lump).

I don’t imagine I touch my neck very often, but somehow yesterday while I was eating breakfast, I happened to discover a very large lump on my throat. “Something is not right,” I realized, in Miss Clavel style, and it was an interesting realization because I spend as much as any woman does examining my body for lumpy things, and being that bodies are quite lumpy in and of themselves, I’d always wondered how you’d know when you found a real one. But it’s like love, I guess, and orgasms. I got up from the table and announced that I had googling to do. I kept googling to a minimum as you always should whenever anything is actually wrong, and made an appointment with my doctor. She saw me later in the afternoon, and couldn’t believe I hadn’t noticed the lump before. But then, as I’ve stated, I don’t touch my neck very often. The lump, she says, is on my thyroid, and feels more like a cyst than a nodule (and therefore, hopefully, less likely to contain nasty things). It is probably huge because I am pregnant, and pregnant bodies don’t do anything half way. She told me I am not to worry. I have an ultrasound next week which will confirm just what the lump contains. It is likely we won’t have to worry about what to do about it until after the baby is born. She said, “You’ve got bigger fish to fry anyway” (ie having a baby, who is, I am grateful to say, bigger than the lump).

I am writing about this here not be melodramatic, but because the more I’ve talked about it, the more ordinary and okay matters have seemed. It helped considerably when I realized that Betty Draper too had had a lump on her thyroid and that she was fine. (I also had a funny conversation with my mom about how we’d tried desperately to have me diagnosed with thyroid problems when I was a teenager, but it turned out that I was just fat because I went through entire tubs of cheez-whiz in a weekend. There was, sadly, no other excuse.) I am writing about this here really to be the opposite of melodramatic, because keeping my anxieties to myself would only make me crazy and because the likelihood of everything being fine is as such that being a brave, desperate martyr isn’t really called for. There is sort of a script for these sorts of situations, in which I start imagining my children growing up without me, planning my own funeral, and things being as they are, following this script would be more self-indulgent than anything else. We will save the panic and melodrama for when it’s really required. And while it’s easier to follow the script, really, because it’s a script, it’s not a useful script. It is always helpful to remember that one is not a character in a television drama. It is always better to face troubles as they are, as they arrive. To not jump so far into the future. To do otherwise is a waste of a life.

And so, onward. This post resonated with me”: “I want to be strong. I think I am strong. But sometimes I wonder, at what point does “strength” become “unwillingness to appear weak”?” But then we’re all constructed of various strengths and weaknesses, aren’t we? We’re all vulnerable, and sometimes that vulnerability is the clearest sign we have that the world and everything we love in it is real.

Update: It occurs to me that this is a situation for which Caroline Woodward’s and Julie Morstad’s Singing Away the Dark comes in handy.

Update 2: I am feeling far less morbid and dramatic a few days later. Looking forward to an ultrasound this week that will confirm that all will be well. And in the meantime, are people ever kind. Thank you for your kind comments and emails, for tracking down second opinions, and offering to refer me to your thyroid specialist doctor dad. I sure do have some fine people looking out for me. And it’s much appreciated. xo

February 21, 2013

On my amateur theatre-going and literary criticism

Even though we would have much preferred to go bed at 7pm, Stuart and I dragged ourselves out the door on Friday night to see Do You Want What I Have Got? A Craigslist Cantata at the Factory Theatre. And we’re so glad we did, because basically the show was 80 continual minutes of us laughing. Stuart and I aren’t the most sophisticated theatre-goers, not least because Stuart and I aren’t the most sophisticated anything. We’re always a little bit disappointed by any play that does not contain song and dance, and the highest compliment we could think to pay to Do You Want What I Have Got? was, “It was a lot like Alligator Pie!” (Which is a high compliment. Really.) Really, our immediate response to most theatre experiences is a gleeful exclamation of, “We are at a play!!” Definitely not an outing to be taken for granted.

Even though we would have much preferred to go bed at 7pm, Stuart and I dragged ourselves out the door on Friday night to see Do You Want What I Have Got? A Craigslist Cantata at the Factory Theatre. And we’re so glad we did, because basically the show was 80 continual minutes of us laughing. Stuart and I aren’t the most sophisticated theatre-goers, not least because Stuart and I aren’t the most sophisticated anything. We’re always a little bit disappointed by any play that does not contain song and dance, and the highest compliment we could think to pay to Do You Want What I Have Got? was, “It was a lot like Alligator Pie!” (Which is a high compliment. Really.) Really, our immediate response to most theatre experiences is a gleeful exclamation of, “We are at a play!!” Definitely not an outing to be taken for granted.

Anyway, we loved Do You Want What I Got?, which was funny, smart and really well-executed. And it wasn’t just whimsy–there was meaning behind it too, that eternal story of the human condition, looking for connection in a crazy world. The show runs until March 3, and I’d urge anyone who can to check it out in the meantime.

There is a point beyond this, however, and it is what I take away from all of this in my position as literary critic/book reviewer. Now, Do You Want What Have Got? has received excellent reviews, but I’m always amazed by the criticisms that manage to turn up whenever I read a review of a play I loved. “How could the critic have noticed that?” I wonder. “Of all the things to focus on…” I think that criticism is really important, essential even, but part of me that feels that critics miss out on the unified experience, that they never get the pleasure of fidgeting in a seat and thinking, “We are at a play!!” It takes so much more to wow a critic, and that’s the critic’s loss.

But not entirely, of course. Being ill-informed and therefore wowed by mediocrity is really nothing to be proud of, and it’s probably better to be eternally dissatisfied. But still. I think critics have to strike a balance, to understand how the common reader/theatre-goer will be greeting the experience, what that impact will be. And I think the critic has to hold on to that wonder, that sense of, “Holy cow! This is art! I am lucky to be here.”

February 20, 2013

The Rosedale Hoax by Rachel Wyatt

“We started out, if you want to begin at the beginning…, an army of professional people, branching out to change things, in this lousy city, to make it great. All of our cells were full of energy. Each of us was a mass of creativity and talent. We were going to do great things as young men and women dream of… Maybe the tall buildings were too much for us because now we walk along long streets, carrying our briefcases with our heads bowed, to talk to each other across polished tables… The gold and silver skyscrapers are very new and quite beautiful but they distort the images of everything around them. You’d think, wouldn’t you, that our daily feet, give us this day our daily feet, beating the same tracks would have worn the sidewalk to a groove….” –Rachel Wyatt, The Rosedale Hoax (Published by House of Anansi in 1977).

“We started out, if you want to begin at the beginning…, an army of professional people, branching out to change things, in this lousy city, to make it great. All of our cells were full of energy. Each of us was a mass of creativity and talent. We were going to do great things as young men and women dream of… Maybe the tall buildings were too much for us because now we walk along long streets, carrying our briefcases with our heads bowed, to talk to each other across polished tables… The gold and silver skyscrapers are very new and quite beautiful but they distort the images of everything around them. You’d think, wouldn’t you, that our daily feet, give us this day our daily feet, beating the same tracks would have worn the sidewalk to a groove….” –Rachel Wyatt, The Rosedale Hoax (Published by House of Anansi in 1977).

More than two years after I read it for the first time, Amy Lavender Harris’ Imagining Toronto continues to play a huge role in my reading life, and has led to so many amazing literary discoveries. It was because of Harris’ book that I noticed The Rosedale Hoax by Rachel Wyatt in the pile at a used book sale a year or so back. And it was probably also the reason too why I became intrigued by Wyatt’s 2012 novel Suspicion, which I enjoyed very much last summer (and decided was the Canadian version of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl). In my review, I wrote, “Suspicion is a literary trick masquerading as a great suspense novel, a story with meta-elements in which characters must reconcile the fact that they’ve become characters.” More than 30 years before, The Rosedale Hoax had taken a similar approach, but satirizing upper-crust Toronto instead of small-town life, and with characters who are all too ready to cast themselves in the story of their lives.

I had some difficulty settling into The Rosedale Hoax, mostly because Wyatt casts her reader straight into the deep end, does not go to great lengths to delineate context, and takes great joy in language and its tricks. The first sentence of the novel is, “On the wall opposite was a picture of Elsa as Miss Niagara Wholesome Fruit 1967.” Elsa is the mistress of Bob Ferrand, nuclear engineer whose career is being held-up by government bureaucracy (turns out the Ontario government has been less than determined about power plants for awhile now), and whose marriage to the wonderful Martha has grown stale. Bob is the son of a peach farmer who has married well, and is raising his family in the same Rosedale home his wife grew up in. Ever conscious of his status as outsider, Bob seeks solace (and stems boredom) in sex with the former Miss Niagara Wholesome Fruit who lives in an apartment around the corner. He comes home in early morning light before his wife returns from her night shift as doctor at the hospital emergency room. Unbeknownst to Bob, though, his odd comings and goings are being spied by his peculiar poetess neighbour who has decided to take him as her lover. And there are other, even stranger forces at work–blackmail letters are turning up in the milk box and Bob becomes convinced that the mailman is the culprit, or the milkman, or the paperboy.

Anyway, about midway through, I was enjoying the ride, and found The Rosedale Hoax to be completely hilarious. I love that the 82 year-old Wyatt could release two novels decades apart that are both so very much of their time (and yet the older one not even remotely dated). There is a dark humour and deep sense of whimsy running through both books. A fantastic use of different voices too–it is not surprising that Wyatt has spent most of her career writing for radio. I’ll be keeping an eye out for her other novels, and you should defintely look out for this one.

February 19, 2013

My review in The Rusty Toque

I am very excited to have a review appear in the new issue of The Rusty Toque, because it puts me in good company, and because I get to go about literary criticism at length. From my review of Alix Ohlin’s books Signs and Wonders and Inside:

I am very excited to have a review appear in the new issue of The Rusty Toque, because it puts me in good company, and because I get to go about literary criticism at length. From my review of Alix Ohlin’s books Signs and Wonders and Inside:

“Read enough of Alix Ohlin’s new novel and the word “inside” becomes conspicuous, begins to assume invisible italics everywhere you spy it. For example, in the following sentence: By this point, it’s impossible to review either of Alix Ohlin’s new books inside a vacuum.

Ohlin’s novel, titled Inside, was nominated for the 2012 Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, and even endorsed by Oprah. On the flipside of all the hype, both Inside and Ohlin’s short story collection Signs And Wonders were the subject of a spectacularly nasty review in the New York Times, critic William Giraldi declaring Ohlin’s use of language to be “intellectually inert, emotionally untrue and lyrically asleep.” Borrowing the “immortal coinages” of a few dead men and employing clichés of his own, Giraldi takes care to define Literature proper and situates Inside far outside its bounds. (I will cease with the italics now, but you see what I mean.)

So the reviewer encounters these books now with an awkward self-consciousness, and, though Inside and Signs and Wonders both deserve to be considered in their own rights, each book as a self-contained universe, the world beyond can’t help creeping in.”

Read the rest here.

February 17, 2013

Capital by John Lanchester

I wanted to read John Lanchester’s novel Capital partly because I enjoy his writing in the London Review of Books, but mostly because Matt Kavanagh’s review of the book in The Globe & Mail made me crazy. This paragraph in particular:

I wanted to read John Lanchester’s novel Capital partly because I enjoy his writing in the London Review of Books, but mostly because Matt Kavanagh’s review of the book in The Globe & Mail made me crazy. This paragraph in particular:

[Capital] gets off to an ingenious start, prompted by the realization that “houses had become so valuable to people who already lived in them, and so expensive for people who had recently moved into them, that they had become central actors in their own right.” For a culture where mortgages are equivalent to a secularized notion of fate (whether you believe in a kindly God or a cruel one depends entirely on the movement of interest rates), Lanchester’s insight is the basis for a revitalized social novel that reveals how the abstract realm of economic relations structure everyday experience.

Have neither Kavanagh nor Lanchester himself ever read an English novel? Particularly those with such central characters as Pemberley, Thornfield Hall, Wuthering Heights, or Brideshead? Even Darlington Hall, or Hundreds Hall more recently. How about Howards End? And speaking of a “social novel that reveals how the abstract realm of economic relations structure everyday experience”, how about Howards End again? Or Pride and Prejudice? Not an English novel, but the best contemporary novel I’ve read yet to deal with the 2008 financial meltdown is Anne Enright’s The Forgotten Waltz, a novel which is profoundly about real estate, but then what novel isn’t? (I love this line from Enright’s book: “You think it’s about sex, then you remember the money…”) And not a novel at all, but what about Three Guineas? A Room of One’s Own? Abstract realm indeed.

Kavanagh’s review was as irksome as it was familiar, a critic lauding a male writer for venturing into female territory (because what is a novel about houses than “domestic fiction” after all?) and declaring that territory still yet to be explored. I wanted to read Lanchester’s book in order to understand if anything new was really at work here, and also because it seemed like the kind of novel I would probably enjoy.

“…immensely enjoyable, but important too.” So goes Claire Messud’s blurb on the novel’s back cover, and she’s right on both accounts if we assume “important” to mean, “notable non-fiction writer makes up tales based on current events”. The “enjoyable” part is pretty straightforward, Capital being a novel that is not altogether novel and which relies on traditional narrative shapes and patterns. Its heft is mainly in page count only (500), and the pages fly by in this story of colliding, disparate and parallel lives. They mainly take place on Pepys Road, a street in London whose homes were built in 19th century to cater to lower middle-class families but which had become, in the 21st century, residences for the rich: “The thing which made them rich was the very fact that they lived in Pepys Road. They were rich simply because of that, because all the houses in Pepys Road, as if by magic, were now worth millions of pounds.”

The residents include the Younts, Arabella and her husband Roger who works for a bank in The City and begins the novel urgently calculating the likelihood of his million pound bonus, whose acquisition has become vital in order for the family to sustain their extravagant lifestyle. At the other end of the scale is Petunia Howe, in her 80s and growing frail, her daughter struggling with an awareness that her mother’s death is going to make her a very wealthy woman. In between them live an African footballer, a family of Pakistani immigrants who run and live above the corner shop, and coming and going are the Polish builder (who is hired three times by Arabella Yount to paint the same wall a different shade of white), the Hungarian nanny, and the Zimbabwean traffic warden who is working illegally.

Kavanagh’s analysis of Capital is interesting when he remarks that the book “seems to ignore the lesson of [Lanchester’s earlier non-fiction book] I.O.U.: However individualistic our culture may be, the financial crisis reveals that we’re all in this together. The novel’s characters seem oddly unaffected by one another, particularly in their encounters with others outside their own station.” The characters in Capital only come together briefly for a community meeting after a strange campaign involving somebody leaving postcards on every doorstep with images of each of the houses on Pepys Road, marked with the note, “We Want What You Have”. Someone is photographing the houses, and also filming them, posting the images on the internet, and the residents of Pepys Road are uncomfortable with this attention. (“They love it… It’s that great British middle-class battle cry: “Something must be done!”… They’ll stop at nothing once they get their indignation going… It gives them an excuse to talk about property prices. It’s the only time they’re ever allowed to talk openly about money, so it’s no wonder it gets them excited.” )

Lanchester’s observations about the English and their peculiarities are one of this novel’s great charms, particularly as seen through the eyes of the book’s non-English characters. The trouble, however, is that rather than functioning as actual characters, Lanchester’s people are so forced to stand for England proper that they are types instead of individuals. No one ever takes a ride on a train or in a car without conjecturing about city and nation flying by outside the window. Everything here is functioning on a grander scale.

Capital is a novel that calls to mind the works of Zadie Smith, partly because it revisits ideas of a multicultural England and also of religious extremism that she wrote about in her first novel White Teeth. But also because Capital is similar in approach to Smith’s latest novel NW. While NW was a novel as flawed as it was ambitious, its reach counts for something. Smith understood that to write a novel which recreates a city, the shape of the novel itself would have to be recreated too, pushed further beyond the linear, the grid of well-drawn careful streets. She understood further that for a novel to truly encompass the diversity of characters she was writing about, she would need to employ a similar diversity of narrative styles. The shape of the world of Lanchester’s illegally-employed traffic warden, for example, would have to be vastly different from the well-born City banker. While both walk the same streets, those streets are not the same at all to each character, and moreover, their paces differ, as does their language, the rhythm of their thoughts and ideas.

For Capital to be successful as a piece of literature instead of merely “enjoyable and important”, Lanchester would have had to demonstrate this narrative divide, and he doesn’t even attempt to. Though it is possible that his novel is more enjoyable for the lapse, from the point of view of anyone who loves an absorbing and unchallenging read, but for this reason and others, Capital is certainly less important than we’ve been lead to believe.