October 29, 2024

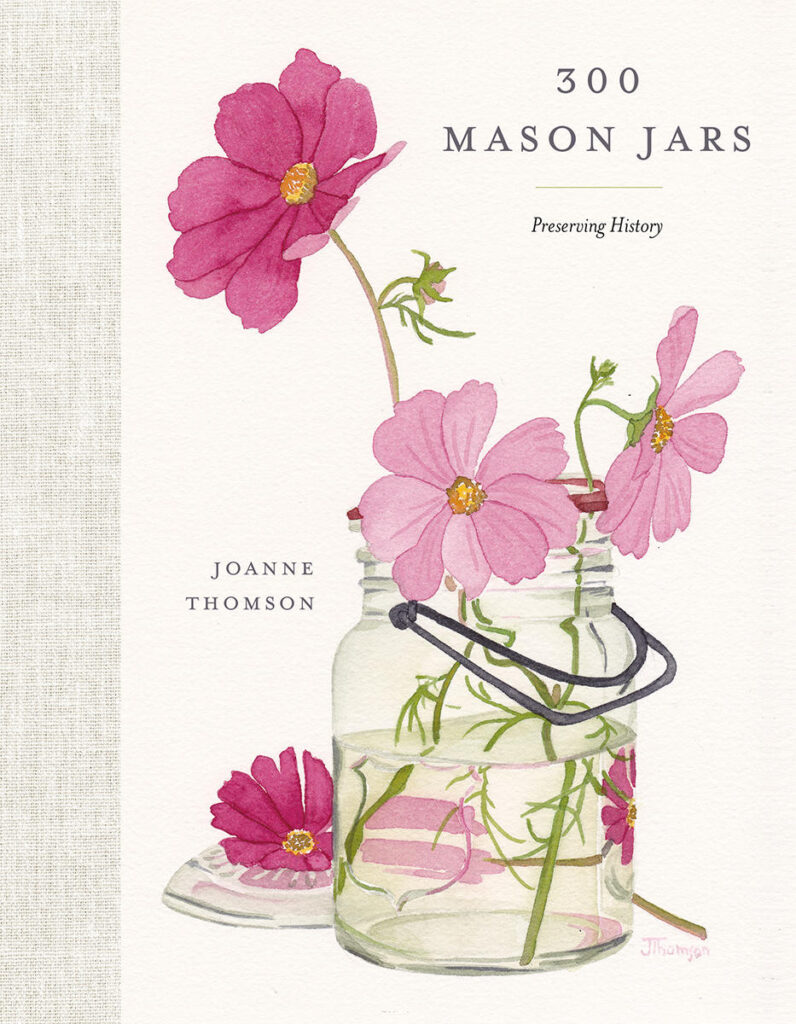

300 Mason Jars, by Joanne Thomson

It’s curious that 300 Mason Jars is such a personal book, inspired by the author’s history, because it also feels like a book that was created just for me, the cosmos in a jar on the cover as familiar as the one on my kitchen table, but it’s the ordinariness of this image, and of the other quotidian objects preserved in the paintings on its pages—crochet hooks, sugar tongs, a pair of scissors, a yellow pencil, along with many plants and flowers—that has this effect. Joanne Thomson is telling her own family’s story through her series of paintings of objects in Mason jars, a riff on preservation that had me thinking about Mary Pratt’s own paintings of jars and scenes of domesticity, but this images will have viewers/readers recalling their own histories, whether their own families were Canadian settlers in the 20th century, as Thomson’s are, or if their stories are different and there would be other objects on display in their jars. There is a sense of play and whimsy to this project—”Mason jar with pliers”; each painting is accompanied by a short piece of verse—but also a real gravity to it, the project inspired by painful parts of her family’s story that Thomson’s ancestors didn’t talk about it, but she brings it to the light of day, light being the very point (Mary Pratt again!) and she imbues it all with such beauty. This book deserves a special spot on Canadian coffee tables, to be flipped through, and returned to, time and time again.

October 22, 2024

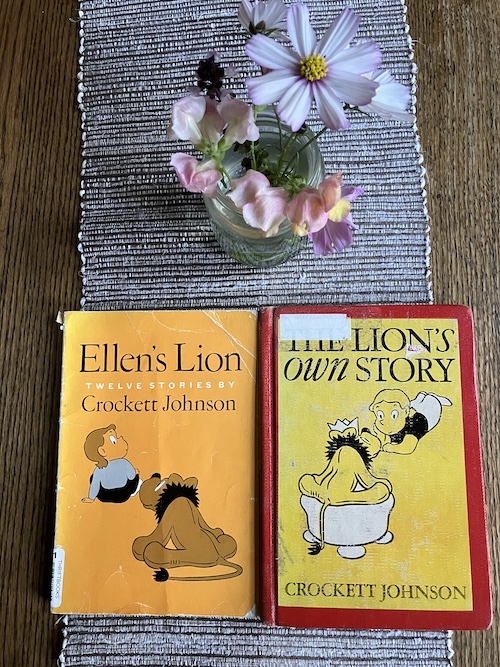

Ellen and the Lion

One of the most interesting things about raising kids in our neighbourhood has been our proximity to the Lillian H. Smith Library, home to the Osborne Collection of Early Children’s Books (which plays a cameo in my most recent novel!), and whose circulating collection was born out of the Toronto Library’s Boys and Girls House, the first dedicated children’s library in the British commonwealth. When the Lillian H. Smith Library opened on College Street in 1995 (named for the first head of Toronto Public Library’s Children’s Department), the Boys and Girls House collection moved in, which means that on the shelf with books by all the authors you might expect (Shirley Hughes, Jon Klassen, Ruth Ohi, Pat Hutchins, Ezra Jack Keats, Mo Willems) are some obscure vintage gems you might not find at other branches that haven’t been around since 1922, usually trippy 1960s picture books (SPECTACLES, by Ellen Raskin!), and the most legendary of all of these for me (I loved them so much I ended up ordering my own secondhand copies online) has been the two Crockett Johnson books (he of the HAROLD AND THE PURPLE CRAYON fame) about an imaginative girl called Ellen and her stuffed lion, each book a collection of stories, mostly text, and they’re so wonderful, tricky, and funny. Now that my youngest is 11 and we don’t read picture books together so often anymore, we do enjoy these stories and taking turns with the deadpan dialogue.

The bane of my existence, however, is that if you google ELLEN’S LION and the title of Mo Willems’ 2011 book HOORAY FOR AMANDA AND HER ALLIGATOR, the sole search result is the blog post I wrote in 2013 about how Willems was surely inspired by Johnson’s book. And all I want in the world is somebody else to talk about this with, the wit and warmth that these books have in common.

October 21, 2024

Death of Persephone, by Yvonne Blomer

I walked home reading this book on Saturday evening, the setting sun turning the tall buildings east of us golden, and it felt like the book was casting a spell. I was a woman walking in the city reading a book about women walking in the city, a riff on the myth of Persephone told through poetry structured as a detective story, and this book was doing it all, the plot, the language, the allusions, the truth of it. Blomer’s Persephone in Death of Persephone is Stephanie, a young woman who’s grown up in the tunnels beneath Montreal where her Uncle H. runs a souvlaki stand, her story punctuated by case notes from Detective Inspector Boca, investigating a series of violent deaths by young women throughout the city. Each poem taken on its own is a marvel, colours ever-changing when it’s held up to the light, but they come together to take on the rhythm of a gripping crime novel, a fierce feminist tale and who dunnit is misogyny. From “Violence is a bone in the body”: metatarsal, metacarpal, maxilla,/ mandible. How violence bites.”

October 18, 2024

The Rich People Have Gone Away, by Regina Porter

I had no idea what I was getting into when I started reading THE RICH PEOPLE HAVE GONE AWAY, a Covid-era novel by Regina Porter, a book that came to my attention via Maris Kreizman’s wonderful substack. A novel whose first section begins with an encyclopedia definition of “door”: “barrier of wood, stone, metal, glass, paper, leaves, or a combination of materials, installed to swing, fold, slide, or roll in order to close an opening to a room or building,” the novel’s following two sections beginning with similar definitions of “doorframe” and “threshold.” And Porter’s doorway/opening to the novel itself, (which is to say, her book’s first paragraph): “Mr. Harper takes sex in doorways. Halts new lovers at the threshold of his front door. Left hand on shoulder. Right hand on hip. He searches the ninth-floor hallway for furtive eyes before pressing the whole of himself in the tender nook of his lover’s ass.” I mean, what now?

Nothing is what it seems in THE RICH PEOPLE HAVE GONE AWAY, set in March 2020 as the world has shut down, neither Mr. Harper himself, who is Theo, presumed suspicious when his young pregnant (white) wife Darla (a bassoonist) disappears on a hike near their cottage in upstate New York, nor the teen in the Cardi B t-shirt who seems to be loitering in Theo’s Park Slope building, nor Darla herself with her secret skills in hotwiring vehicles, or her father, who perished on 9/11. Porter is also an award-winning playwright, and the novel’s playful heteroglossia has those skills on display, resulting in a dynamic and shapeshifting text, full of tricks but never cheap ones, missing white lady/GONE GIRL tropes turned inside out and on their noses, and it’s all so interesting. The narrative moving swiftly through that strange and harrowing season (the teen in the Cardi B shirt’s mother is hospitalized with Covid; she comes off her ventilator; she goes back on her ventilator…) to late spring, late May, the teen boy’s phone blowing up, Minneaopolis, another threshold. “Did you see it?” No resolution. A story without end, but that is also what makes the novel particularly satisfying.

October 16, 2024

Another Year of the TURNING THE PAGE ON CANCER Read-a-thon

Five years ago, I embarked upon my very first TURNING THE PAGE ON CANCER fundraiser, and was in love with founder Samantha Price Mitchell (in the photos above) right out of the gate. First, because she was just lovely, and brave, and honest, and awesome, but also because she dreamed up a cancer fundraiser for those of us who’d rather not run (some of my favourite parts of the population, to be honest), for those of us who love nothing better than sticking our heads in a book, and who’ve been training our whole lives for such a thing as a “read-a-thon.”

I met Sam through my friend Melanie, who was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer in 2016, and who loved books as much as I do (we’d met online through Canada Reads in 2009!), connecting me with Turning the Page on Cancer, whose proceeds go toward Rethink, supporting research and better outcomes for women living with MBC through. Sam was also a book lover, and had just landed her dream job as a merchandiser at Indigo before her diagnosis, and I was so grateful to her for giving me this way to support my friend and raise money for a good cause. And through our online connection, Sam became a friend too, and I’m so happy to remain connected with her family and to be helping to carry her generous legacy on.

Sam died in July 2021. She was 30. Melanie died on the winter solstice that December. She was 45, a mother of three. Sam and Melanie both had so many books still to be read…

And so we’ll be reading for them, and if you’d like to join us, it’s not to late to sign up for your own read-a-thon. If the idea of spending EIGHT STRAIGHT HOURS READING is beyond your athletic abilities, then please donate to the campaign if you’re able.

October 16, 2024

Keep, by Jenny Haysom

I’ve been reading all over the place lately, out of necessity, sometimes seven books at at time, bits and pieces, and so it was quite delightful to fall into a novel for the first time in a long time, to read the whole thing in a day. I loved KEEP, by Jenny Haysom, a novel following her award-winning debut poetry collection DIVIDING THE WAYSIDE. KEEP is the story of two real estate stagers charged with packing up the life of Harriet, an elderly poet with dementia, who become entangled in the mess of her life. Although their own lives are not so tidy either—Jacob, in his early 20s, has just been dumped by the boyfriend he moved to Ottawa to be with, having tried and failed to conjure domestic bliss for them; Eleanor, 20-some years older, is dissatisfied with her own domestic arrangement, the small home she shares with her husband and three children altogether too confining, everybody relying on her labour to make it work, and she’s exhausting. KEEP is a novel about building home, about keeping house, about what life does to everybody’s best intentions, and the distance between the faces we present to the world and the realities we’re actually facing. The braided narrative is so well balanced, each character a vivid and engaging presence in the novel, and it’s interesting (and refreshing!) to encounter a book presenting three different generations together and the genuine connections between them.

October 16, 2024

Love is a Mixtape

At the turn of the century, almost all of the romantic love I had to give was unrequited, and the only problem with that (in retrospect) was that I never got to realize my dream of having a boyfriend come along to digitize my vast collection of mixed tapes, and then burn them onto CDs. And I suppose I could have done like Dalloway and digitized the mixtapes myself, but I didn’t have my own internet connection back then, let alone a CD burner, and besides, it used to take entire afternoons to download half a song, and burning a CD could take even longer, and the only people with patience for such projects were the kinds of emotionally stunted, technically-inclined dorks that I tended to have crushes on, and none of them ever cared about me enough to do so.

So my trove of mixtapes was lost to time, from “Britt’s Mix 93” to the ska tape our friend Laura made in 1997, that very random tape I made in Grade 10 that went from April Wine’s “I Wouldn’t Want to Lose Your Love” to Alannah Myles’ “Lover of Mine,” and that most iconic Summer of ‘99 tape whose Side B began with Sophie B. Hawkins’ “As I Lay Me Down” to Mariah Carey’s “Always Be My Baby” (and “Angels” by Robbie Williams in there somewhere).

And yes, it’s true that if any of those CD burner-owning boys I’d fancied had ever managed to love me back, the attraction might have petered out around the time they discovered the extent of my affinity for soft rock. The one guy I did go out with during this period didn’t have a CD burner either, but when I gave him a tape that included Heather Nova’s “London Rain (Nothing Heals Me Like You Do),” he was really mean about it, which should have been a red flag—nobody puts a track from the Dawson’s Creek soundtrack in the corner. (Full disclosure: his mixtape for me was really cool, introducing me to music I love to this day, but he was not very nice in the end.)

Mixtapes, for me, in the 1990s, were almost like a scrapbook, compiled in real time. My Sony Sports Walkman was always nearby, and I’d be listening to the tape-in-progress, removing the tape from my deck only to add to it, taping something off a friend’s CD, recording a song off the radio, or from somebody’s parents’ record collection. And then once the tape was complete, it would be titled and dated, a record of time, much of the music not actually contemporary, assembled by chance, but that would become my soundtrack as I made my way through the world, foam headphones ever-present on my ears (at least until I stepped on the headset and broke it, which happened all the time).

My husband never made me a mixtape. We met in 2002, and he’d already embraced the future, a never-to-be-obsolete technology called the minidisc (ha ha) and he brought me on board, for which he still regularly apologizes. He must have made me a mix-minidisc, but I don’t remember what was on it, mostly because there was so much else going on at the time, our separate lives converging, the beginning of forever. In 2005, under the impression of an iconic ad, we each purchased an ipod shuffle (catchphrase: “Life is random”), which was the start of the end of our relationship with physical media (although we still own an entire shelf unit of CDs).

But the ipod shuffle would not be the the end of us sharing music together, on road trips, in the kitchen doing dishes. My husband has a Spotify playlist called “The Kerry List” that is 2 hours and 26 minutes long, specially curated at the intersection of our tastes, and while there’s no Mariah Carey, every single track is one that makes me exclaim, “Tune!” at the opening strains, and to me there is nothing more generous.

Including “London Rain (Nothing Heals Me Like You Do).”

Love is a mixtape, indeed.

October 16, 2024

BOOKSPO Season Two

7/10 episodes of the BOOKSPO podcast are up now (with more to come on the next three Wednesdays). I’m also so pleased to report that the podcast is now available on Spotify, along with Apple Podcasts, Substack, and (pretty much) everywhere else you get your podcasts.

Guests so far are Corinna Chong, author of the Giller-longlisted BAD LAND; Ayelet Tsbari, author of SONGS FOR THE BROKENHEARTED; Alice Zorn, author of COLORS IN HER HANDS; Marissa Stapley, author of THE LIGHTNING BOTTLES; Suzy Krause, author of I THINK WE’VE BEEN HERE BEFORE; Jennifer Whiteford, author of MAKE ME A MIXTAPE; and Anne Hawk, author of THE PAGES OF THE SEA. More to come!

October 15, 2024

Toxemia, by Chistine McNair

TOXEMIA‘s gorgeous cover (a collage by @rhinocerospoems) sets the reader up for what’s to come, the literary bricolage, a hybrid of memoir and poetry. “To Lady Sybil,” the book is dedicated, the character from DOWNTOWN ABBEY who died of pre-eclampsia in the show’s third season (after which I refused to watch any more because *how could they have done that?!*). Christine McNair blends high and low cultures, arts and science, words and images, memoir and research to tell the story of her life as a woman with a body, a body that is so often wrong or dangerous, her symptoms and experience disbelieved, disregarded. McNair’s experiences of pre-eclampsia during her two pregnancies don’t just have consequences for her mental and physical health in the years afterwards, but also tap into her experiences with depression, self-harm, and eating disorders. “I am now more afraid of telling doctors my history,” she writes. Though with TOXEMIA, she’s made art of that story, a moving and compelling narrative, strange and edgy, unsettling. Unputdownable.

October 10, 2024

The Accomplice, by Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson

I will admit that I first picked up 50 Cent’s debut novel because I found the idea of a novel by 50 Cent really funny, but when I opened up THE ACCOMPLICE, I was surprised from the very first line: “Nia Adams doesn’t have a green thumb, but waters her garden diligently, cares for the soil, tends to the flowers, and tames the weeds. Her favourite perennial is the Lupinus texensis, the Texas blue bonnet. The bright blue petals are the showpiece of her front yard. The flowers thrive on full sunlight and damp soil and are resilient during dry spells. Like Nia, they’re survivors.”

With delight, I can tell you that I loved this book, the story of Nia Adams, the first Black female Texas Ranger, whose fate becomes bound up with that of Vietnam-vet turned thief Desmond Bell after a bank robbery goes very strange with nothing of value appearing to be stolen. The lines between good guy and bad guy, and right and wrong, becomes blurred as we learn more about Bell’s story and as Adams comes to understand her colleagues and the institution she works for.

Written in partnership with crime novelist Aaron Philip Clark, THE ACCOMPLICE is a deft thriller with proper twists and turns, and is absolutely gripping. The only thing that tripped me up was some fairly gruesome violence in a couple of parts, but thankfully the story doesn’t linger there, instead tackling big questions about history, race, power and the possibility of redemption. And 50 Cent even makes a cameo in the text, or at least his music does, when “P.I.M.P.” is being played on somebody’s karaoke machine—Desmond Bell unplugs it.

It’s all a little ridiculous, but I’d be disappointed if it wasn’t.