March 17, 2014

After Alice by Karen Hofmann

What a pleasure is spending a weekend devouring a book, and for me this weekend, that book was After Alice by Karen Hofmann, which I absolutely adored. It was the most unCanLitty CanLit I’ve encountered in ages, the story instead calling to mind English novelists like Anita Brooker and Daphne DuMaurier, and then Wallace Stegner, Barbara Kingsolver and Joan Didion in its evocation of place. This is a debut novel by Hofmann, whose previous poetry collection was shortlisted for the Dorothy Livesay Prize in 2009, but she writes with a touch so rich and deft that there is nothing of the debut about it.

What a pleasure is spending a weekend devouring a book, and for me this weekend, that book was After Alice by Karen Hofmann, which I absolutely adored. It was the most unCanLitty CanLit I’ve encountered in ages, the story instead calling to mind English novelists like Anita Brooker and Daphne DuMaurier, and then Wallace Stegner, Barbara Kingsolver and Joan Didion in its evocation of place. This is a debut novel by Hofmann, whose previous poetry collection was shortlisted for the Dorothy Livesay Prize in 2009, but she writes with a touch so rich and deft that there is nothing of the debut about it.

There’s a lot going on here: Sidonie Von Täler has retired from her academic job in Montreal designing computer models for psychology experiments. Sidonie herself is something of a cold-fish, so this seems a job to which she’d be unusually suited. We’re locked into her point of view, and it soon becomes apparent that something is just askew–she is a synesthete, displays some symptoms of Aspergers in her perception of the world. Which is not to say that Sidonie’s point of view is the point of this story, that this is a novel or that she’s a protagonist we’d ever refer to as “quirky” ala Come Thou Tortoise or the Dog in Nighttime, but just that she’s a bit peculiar. Her point of view is fascinating, and her voice is sharply defined.

She’s returned to the Okanagan Valley where she’d fled from years before. In her childhood, her family’s orchard had been one of the biggest in the area, their land defining every circumstance of their existence and their status in the community. Sidonie, ever awkward, had been raised in the shadow of her beautiful sister, Alice, whose tragic later circumstances we’re not made aware of until later in the book. Upon her return, Sidonie gets to know her sister’s sons and their own family’s. She’s also close to her niece, Cynthia, whom she’d raised after Alice’s death, and Cynthia’s son, Justin, though much goes unsaid between all of them, Sidonie choosing to believe that she prefers her independence to the complications and niceties of family ties.

And you can’t blame her–Sidonie is brilliant, accomplished and self-succificent, having left a life rich with culture and a couple of close, rewarding friendships back in Montreal. She’d married well–an architect who built Habitat 67 in Montreal, where they’d lived until their marriage ended. She looked upon her marriage not warmly, but as coolly as she did everything. Some might find her life lonely, but there is no sign that she does. But something has driven her to come home, to a past that refuses to stayed packed away in boxes.

After Alice has mystery at its core, and while its approach is most literary, Hofmann has combined that approach with well-tuned plot that makes this book a page-turner. It is also very much a book about place, though not sentimentally so–Sidonie doesn’t do that–but instead the details of the land and what grows there, what it means to work that land in terms of economics and physical labour. It’s a novel that might take a place on the shelf beside Kingsolver’s Animal Vegetable Miracle or The Hundred Mile Diet in its consideration of the terroir, what the land does to its people. And what times does too, Hofmann weaving past and present together, Sidonie’s family home casting a spell that makes it difficult for her to tell where one of them finishes and the other begins, though it’s really that points like this just don’t happen.

Hofman’s prose is lyrical and effective, if a little in need of tautness. And her ending is a little bit too tidy and choreographed, though still with its surprises. But these are minor quibbles for a novel so ultimately satisfying, and so I welcome Hofmann’s refreshing voice with this wonderful book, one of the most interesting and exciting that I’ve encountered in ages.

March 16, 2014

Spring Break

I totally get March Break now. I never really did before. But the weeks leading up to it were threatening to destroy me. Compared to others, we didn’t have it so bad, but we’d had three straight weeks of sick kids, too much going on on the weekends, and the mad scramble that is every day. This year, February didn’t really seem so bad, but I think it was just saving itself for March, which hit with such a wallop. And oh, this long winter. We’ve really had enough, and so, this was the week that came along to save us. Stuart took the week off too, and we did what we do best: a few splendid things, plenty of lunch, a whole lot of nothing, and precious precious time.

Monday was lunch at Caplansky’s, which never ever fails, followed by a visit to the Lillian H. Smith Library for a brand new stack of books. On Tuesday, we took a road trip to the McMichael Gallery to see the Mary Pratt Exhibit, which was oh, so extraordinary, definitely worth a visit. We felt a bit guilty (not really) as we drove past the sign for Legoland, but luckily Harriet can’t read yet, and the Mary Pratt exhibit was engaging for her as well, with all its bright colours and familiar objects. (She likes the hot dog one the best). On Tuesday, we actually wore shoes instead of boots, but any indication that spring was in the air was packed away with Wednesday’s snowstorm, which we walked through to get to lunch at Fanny Chadwick’s and it was totally worth it, even with the snow so wet and awful that my face was burning with cold and so soaked I had to be mopped off when we arrived. Thursday, the sun came out, and we went to the AGO, which was no crowded and had totally excellent stuff on for kids (so I felt better about Legoland), though I have no photos of any of it because I smashed my phone on the streetcar floor (which is made of rubber. How is that possible?). And then on Friday, we had afternoon tea at the Windsor Arms Hotel, and Harriet and Iris were both so totally good—with the former, this is due to her being excellent, the latter is pure luck. It was Iris’s first afternoon tea, and we threw scone pieces her way to keep her happy, and it worked. As ever, it was nice to do something so special.

And now with tomorrow, we’re back to reality, though it will be reality with extra crazy because The M Word is in the world! Which will bring me out of my hermetic existence, which I am slightly dreading, but which I’m also committing to enjoying, because this is such a dream come true.

March 13, 2014

Little You

Little You by Richard Van Camp and Julie Flett is the first book whose content interests Iris just as much as its flavour. This makes me happy because I love it too, and so delight in reading it over and over. The line, “You are mighty/ you are small” describes our littlest girl so perfectly. And then then next line, “You are ours after all,” and I love that too, because ours is what she’s always been, belonging to our whole family, and I’ve loved her even more for that.

At first glance, Julie Flett’s illustrations are simple, though they’re made interesting with different prints and patterns throughout, and I notice new details all the time. Like the Mother’s bright red tights in this in image as she dances with her baby.

And then I looked even closer upon my 180th read to see a hole in her big toe, which is pretty much the story of my life.

Just when I thought I couldn’t like this book any more…

It’s so absolutely perfect.

- Learn more about this book here, how it was inspired by Eddie Vedder, and how it was distributed across the Northwest Territories and published also in Cree, Chipewyan and South Slavey.

March 11, 2014

Bark by Lorrie Moore

I’m still discovering Lorrie Moore, which is a pretty lucky place to be in as a reader. The first book I read of hers was Anagrams, and I just thought it was weird. I really liked The Gate at the Stairs, and then I read Birds of America but I mustn’t have been reading carefully because I don’t even remember it. So when I opened up her latest collection, Bark, I didn’t have the same expectations that her much more devoted readers might have had. I wouldn’t have been able to tell if it was a good Lorrie Moore or a middling Lorrie Moore. As I read it, all I could think was, “So, this is Lorrie Moore,” which was a pretty fantastic revelation.

I’m still discovering Lorrie Moore, which is a pretty lucky place to be in as a reader. The first book I read of hers was Anagrams, and I just thought it was weird. I really liked The Gate at the Stairs, and then I read Birds of America but I mustn’t have been reading carefully because I don’t even remember it. So when I opened up her latest collection, Bark, I didn’t have the same expectations that her much more devoted readers might have had. I wouldn’t have been able to tell if it was a good Lorrie Moore or a middling Lorrie Moore. As I read it, all I could think was, “So, this is Lorrie Moore,” which was a pretty fantastic revelation.

The stories themselves are many-angled, surprising, full of perfectly articulating revelations. On divorce: “It’s like a trick. It’s like someone puts a rug over a trapdoor and says, ‘Stand here.’ And so you do. Then boom.” Or, “It was like being snowbound with someone’s demented uncle. Should marriage be like that? She wasn’t sure.” And, “A life could rhyme with a life—it could be a jostling close call that one mistook for the thing itself.”

No super-narrative tricks or sleights of hand are going on here. As short story shapes go, these ones are mostly standard, riddled with quirk, but then there is this extra-perspective at play in which characters call out surreality of their situations. “He had never been involved with the mentally ill before…” it is noted of a character in the first story, “Debarking,” a guy who’s dating the bizarre quirky kind of woman who turns up in many a short story, a manic pixie dream girl gone very very wrong. All of these are stories of a world gone askew, and its people definitely know it, however powerless they may be against its forces.

The surrealism and sense of askewness is unsurprising. These are stories of America in the first decade of the twenty-first century, the first story situated sometime in the months after 9/11 and before the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The final story begins the day after Michael Jackson died in 2009, and doesn’t offer much hope for the decade to come: “I tried to think positively. ‘Well, at least Whitney Houston didn’t die,’ I said to somebody on the phone.” Foreclosures, banks and big-box bookstores, both. War, fear and Abu Grahib are the backdrop to these smaller stories of domestic disappointment. It got to the point where I was underlining references to decapitation, and there were more than a few. I got the sense that this is a book haunted by the story of Daniel Pearl.

While many of these stories have been published elsewhere, they’ve been collected seamlessly into a curious, fascinating whole that is as much worth remarking on as the stories themselves. The stories are linked by weird decapitation references, and the word “bark” which comes up again and again in a variety of contexts. Trees for one, the bark their protection, as is the case with dogs (which also come up again and again). The question of whether bark is, in fact, worse than bite—just one of many things we’re told that’s patently not true. I wonder if Moore’s bark, our bark, is in fact humour—what saves us from this savage life.

March 9, 2014

The M Word in Waterloo!

Carrie Snyder will be reading from The M Word at Waterloo Indie Lit Night on April 14, along with some other fantastic authors. It’s going to be great.

Carrie Snyder will be reading from The M Word at Waterloo Indie Lit Night on April 14, along with some other fantastic authors. It’s going to be great.

March 9, 2014

For Sure by France Daigle, trans. Robert Majzels

For two weeks, I was reading For Sure by France Daigle, a 719 page novel that doesn’t have much of a plot. However plotless though, For Sure is more useful than most novels I encounter—with its help, I taught my daughter to swim. Seriously. And not just that, but for those two weeks as I lived with this book, a giant doorstop, and its people, strange connections were made between the happenings in their lives and the occurrences within my own. Which is precisely what France Daigle wants me to think. She has no truck with characters or their stories staying within the confines of their pages.

For two weeks, I was reading For Sure by France Daigle, a 719 page novel that doesn’t have much of a plot. However plotless though, For Sure is more useful than most novels I encounter—with its help, I taught my daughter to swim. Seriously. And not just that, but for those two weeks as I lived with this book, a giant doorstop, and its people, strange connections were made between the happenings in their lives and the occurrences within my own. Which is precisely what France Daigle wants me to think. She has no truck with characters or their stories staying within the confines of their pages.

Not least of all because this is the fourth book in her series about a group of people who live and work in converted lofts in Moncton, New Brunswick. In its original French, Pour Sur won the Governor General’s Award for French Literatre in 2012. Though it wasn’t French exactly, but instead Chiac, an Acadian-French dialect mixed with English and Aboriginal influences, spoken by Acadian communities in southeast New Brunswick. Which has been translated into English by Majzels as French-accented English with a Newfoundland bent–“fer sure” for “for sure”, a lot of “dat dem dare.”

The novel is made up of twelve sections, each section broken into fragments, assigned a number code and category. A sense of progression comes from moving through the code rather than the fragments themselves, whose connections are often elusive. (I just mistyped that as “allusive” but I kind of mean that too.) There’s a lot about Scrabble, colours, the names of colours, the colour of letters, attempts to quantify the abstract, apply methodology to slippery things (like novels). An attempt to write the book of Chiac, to put the colloquial down on paper, articulate its rules and laws, but then language is as slippery as a novel after all. And life itself.

There are people here too. At its heart, this is a novel about Terry and Carmen and their small children Etienne and Marianne, and their friends at the lofts where they live, and where Terry works at a bookstore and Carmen co-owns a bar (called Babar). There are little plots, small mysteries, and even a murder (on the periphery). Terry worries about being a good father, they wonder whether their kids might grow up to be gay, they take a holiday, do crosswords, and define their language through acts of every day life. All the characters in the book ponder the mysteries of language and words, and search for meaning in their patterns. Just as the reader of For Sure seeks to put the pieces together in her own right, connect the dots, come up with a whole.

What is most compelling about these characters is their goodness, their aspirations toward such things. And yet that they’re compelling all the same—this is something. They’re flawed too enough to be real, so much so that when France Daigle herself (so we assume) sits down with these fictional people for a chat, and they discuss their place within her narrative and her control over their fates, the conversation is completely plausible, as is the fictional existence of Daigle herself.

More for plausibility: Terry teaches his son to swim by imploring him to try to drown. The boy tries, finds it’s impossible and begins having faith in his buoyancy after all. Which is the same trick I tried the next day after reading this passage, in the swimming pool with my daughter whose relationship to swimming lately has been of an adversarial nature. And it worked! 30 minutes later, she was swimming without clutching another human body for dear life, which is huge. And to think we owe it all to Terry Thibedeau.

It is worth nothing that in reading this translation, rendered in a made-up dialect, there is an enormous gap between what we’re reading and what Daigle and her novel intended. And yet, I think this gap only underlines the novel’s central thesis, which is that precision of language is something of a fallacy. That anything expressed in language is going to be a muddle, a translation. That in reaching toward precision, the reach instead of the precision is always going to be the point.

March 5, 2014

It Was Not What I Expected by Val Teal

We’ve had The Little Woman Wanted Noise out of the library, a picture book by Val Teal and illustrated by Robert Lawson, recently reissued by New York Review Books. Lawson is notable as the illustrator of The Story of Ferdinand and Mr. Popper’s Penguins, though it was Val Teal’s biography that most intrigued me. “In addition to her stories for children,” it reads, “Teal also wrote a memoir of motherhood, It Was Not What I Expected.”

We’ve had The Little Woman Wanted Noise out of the library, a picture book by Val Teal and illustrated by Robert Lawson, recently reissued by New York Review Books. Lawson is notable as the illustrator of The Story of Ferdinand and Mr. Popper’s Penguins, though it was Val Teal’s biography that most intrigued me. “In addition to her stories for children,” it reads, “Teal also wrote a memoir of motherhood, It Was Not What I Expected.”

It Was Not What I Expected is described in this 1948 review as “[s]teering away from sentimentality… a vivacious, gaily turned account of modern parenthood.” I liked the sound of that, as well as any parenting memoir by the author of The Women Wanted Noise, who in her dedication thanks her own three sons, “whose noise inspires the little woman.” The book isn’t easy to come by, long out of print and not held by local libraries, but used copies are available on Abebooks (though that I bought the cheapest I regret now, because it came without a dust jacket).

I had some ideas of what an account of modern parenthood published in 1948 might read like. I had these ideas because a long time ago I’d read Dream Babies: Childcare Advice from John Locke to Gina Ford by Christina Hardyment, which is where I first encountered the idea of babies being aired from apartment buildings in cages. It is also where it was first made clear to me that childcare advice (and “parenting philosophies,” baby fads and gadgets, and dictums everyone from Ferber to Sears) is a complete load of bollocks, and that we ought to cleanse our minds of most of it, except for reasons involving amusement or historical interest. The more things change, the more they stay the same, which is both a cliche, and also Hardyment’s thesis and in this context, such a revelation.

I had some ideas of what an account of modern parenthood published in 1948 might read like. I had these ideas because a long time ago I’d read Dream Babies: Childcare Advice from John Locke to Gina Ford by Christina Hardyment, which is where I first encountered the idea of babies being aired from apartment buildings in cages. It is also where it was first made clear to me that childcare advice (and “parenting philosophies,” baby fads and gadgets, and dictums everyone from Ferber to Sears) is a complete load of bollocks, and that we ought to cleanse our minds of most of it, except for reasons involving amusement or historical interest. The more things change, the more they stay the same, which is both a cliche, and also Hardyment’s thesis and in this context, such a revelation.

For example, here is Val Teal on big strollers, which remain, of course, a contentious issue to this day:

“In those days buggies were built. None of your light canvas affairs. They had a solid steel framework and lots of it. They had a big wicker body and hood with a steel bottom with a diaper compartment large enough to hold a dozen or so. The baby-carriage manufacturers expected you to push the baby on really long trips. If you took the notion to walk to Chicago some afternoon to visit your aunt they would not stand in your way. They had prepared a perambulator with ample space for the baby’s and your luggage during your stay. They expected you to have a big baby and push him around until he was three or four years old and they had provided room for this, with enough left over to bring home the groceries, including a watermelon if you were so inclined. The buggy weighed several hundred pounds, several hundred and fifty pounds with the baby and his paraphernalia aboard. We did not have an extra garage to keep it in. It furnished our small dining room very nicely before we could afford a dining room set. While you pushed this young truck around like mad, your tongue hanging out the baby sat like a rosy king, taking in the world with his round eyes, the air with his pink nose.”

It is often said that nobody tells the truth about motherhood, though I think the reality is really that nobody ever listens. Because Val Teal was telling the truth in 1948, Betty Friedan in 1963 Erma Bombeck in the 1970s, Susan Swan in 1992, just to pick a handful of examples. Some early passages from It Was Not What I Expected were so similar to my own experiences, which had come as such a surprise to me when my first baby was born. Like this one, as Teal and her husband arrive at the hospital for their first baby’s arrival:

It is often said that nobody tells the truth about motherhood, though I think the reality is really that nobody ever listens. Because Val Teal was telling the truth in 1948, Betty Friedan in 1963 Erma Bombeck in the 1970s, Susan Swan in 1992, just to pick a handful of examples. Some early passages from It Was Not What I Expected were so similar to my own experiences, which had come as such a surprise to me when my first baby was born. Like this one, as Teal and her husband arrive at the hospital for their first baby’s arrival:

“Across the street a young couple were just getting home. They were laughing and talking softly as he found the key and put it in the door. We could have been just like that as well as not. We could have been just coming home from a party. Why had I been so eager? Maybe I’d die. Maybe we’d never come home from a party like that again together… We had been so happy. We’d had a good life. Why had I had to get ambitious? Darn it all, I didn’t want a baby. I just wanted to go home and go to parties.”

A few pages later, the baby is born, and mother and son are home:

“The Baby cried and cried. I had given up not feeding him at two in the morning long ago. Every time I fed him he went to sleep for half an hour. Then he cried again.

‘I didn’t know it would be like this,’ I wept to Bill. ‘I wish I was back in the hospital.'”

Motherhood was less complicated for previous generations, Teal explains. She describes a trip when her first son was seven months old, the directions they’d had to send ahead, provisions required, their car ridiculously packed. Along they way, they stop for the baby’s sunbath (as dictated by both government pamphlets and the Women’s Home Companion). She writes, “I used to think about [my mother] being cleaned up every afternoon, baking cakes for visitors, sprinting off peppy as a kitten to coffee parties, pushing her baby-sled full of clean babies, and I wished I’d lived then when babies were less complicated…”

Motherhood was less complicated for previous generations, Teal explains. She describes a trip when her first son was seven months old, the directions they’d had to send ahead, provisions required, their car ridiculously packed. Along they way, they stop for the baby’s sunbath (as dictated by both government pamphlets and the Women’s Home Companion). She writes, “I used to think about [my mother] being cleaned up every afternoon, baking cakes for visitors, sprinting off peppy as a kitten to coffee parties, pushing her baby-sled full of clean babies, and I wished I’d lived then when babies were less complicated…”

It Was Not What I Expected takes great joy in dissecting the naiveté of the new mother, insistent upon raising baby according to the book (what book? depends which decade, I suppose). How stupid we all were in those early days, and how determined we were that we would be the masters of motherhood rather than motherhood be the masters of us. Naturally, hilarity ensues.

Memorable scenes include Teal getting locked in the attic while her son sits outside the door eating beads, and the time she hires a simple-minded creature prone to seizures to babysit as she tries to better herself at a meeting of the American Association of University Women and it all goes wrong. (“I began gradually to give up the International Relations section because Hitler seemed to go right ahead doing impolite and smarty things, even though we met every week with luncheons too, instead of teas.)

And like any mother, she frets about play dates:

“I learned at the Child Study Group that children need companionship. If you child did not have others to play with you must do something about it. You must see that other children came to your house. It was a matter of life and death. Or anyway the difference between success and failure. You must drag in companionship. You must inveigle children to come. You must offer them food and toys, anything, to get them there. Companionship was the breath of life to the normal child.”

Teal’s second child just escapes being born in the Piggly Wiggly. “Now I knew all about babies,” she writes. “Peter would be easy to raise. I was experienced. There would be no foolishness about who was boss. I knew who was boss.” Instead of books to raise this baby, she decides, she’ll employ her own instinct. She will let the baby do what he likes.

More adventures in motherhood with boys: the necessary acquisition of a menagerie, dogs, ducks and rabbits. The obligatory paper-route. She helicopter parents, terrified of her boys riding their bicycles and therefore driving along behind them in the car on the way to their music lessons.

More adventures in motherhood with boys: the necessary acquisition of a menagerie, dogs, ducks and rabbits. The obligatory paper-route. She helicopter parents, terrified of her boys riding their bicycles and therefore driving along behind them in the car on the way to their music lessons.

She addresses her determination that her boys shall play with dolls, much to the concern of everyone around her. To which she replies, pre-dating Charlotte Zolotow, “If more boys had been allowed to play with doll there’d be more intelligent fathers. Boys have been taught for too long a time that it is shameful for men to have anything to do with the care and bringing up of children. Men need tenderizing. I’m going to raise them to, first of all, be kind and loving fathers, and considerate husbands.” This chapter is wonderful, and ends with her son packing his doll (Uncle Pat Mulligan), along with a toy revolver on a trip:

“What have you got that for?” I asked. “Leave [the gun] at home. You’ve got enough to carry.”

“No, I gotta have it,” Peter grabbed for the gun.

“What for?” I asked, holding it back.

“If Pat Mulligan turns bad on this trip I’ll have to shoot him in the stomach,” Peter said.

I gave Peter the gun. You never could tell when Pat Mulligan might turn bad.

Teal’s picture book and her memoir are excellent companions. In the former, the little woman cannot rest without noise and goes out of her way to acquire more and more animals to liven up her farm and fill the air with sound. With that same lust for more, Teal writes in her memoir of her own yearning for a large family, a yearning augmented by a miscarriage and a stillbirth. “What no man, no doctor, no woman who has never lost a child can ever know about, is the consuming desire to replace that child that comes to the woman who has lost one.” The losses are not dwelt on here, but neither are they swept under a rug, instead acknowledged in practical terms as part of the vast motherhood experience.

Teal’s picture book and her memoir are excellent companions. In the former, the little woman cannot rest without noise and goes out of her way to acquire more and more animals to liven up her farm and fill the air with sound. With that same lust for more, Teal writes in her memoir of her own yearning for a large family, a yearning augmented by a miscarriage and a stillbirth. “What no man, no doctor, no woman who has never lost a child can ever know about, is the consuming desire to replace that child that comes to the woman who has lost one.” The losses are not dwelt on here, but neither are they swept under a rug, instead acknowledged in practical terms as part of the vast motherhood experience.

Teal’s narrative is remarkable for its blend of wry humour and depth, of exasperation and joy. She so perfectly articulates motherhood as the curious mix that it is of the spiritual and earthly, the perfect and perfectly awful:

“Sometimes I’d look down and see these children around the house and feel very surprised and young and incapable… My goodness, where had they come from?… How in the world had this come about all of a sudden? They weren’t dolls, dream-figures. They were real, alive children, going-to-be men; dear Heaven, what had I done? I had made people! I had made people, Lord help me, people with emotions and plans and wishes and disappointments and longings. People. With souls. And when it would come over me, I’d stand very still and get very scared and helpless feeling. But they always brought me out of it.”

March 3, 2014

Reading when the world seems unsteady

That time does fly is demonstrated by the fact that once again, I am waiting for test results on my thyroid lump (as I will be six months from now, and six months after that, and if this schedule alters, it’s probably not a positive twist in the story). It is no fun waiting for test results, I am learning, no matter how routine it becomes to get needles stabbed in one’s neck. It is no fun getting needles stabbed in one’s neck either. But the very worst is waiting on test results when one is reading a novel that isn’t very good.

That time does fly is demonstrated by the fact that once again, I am waiting for test results on my thyroid lump (as I will be six months from now, and six months after that, and if this schedule alters, it’s probably not a positive twist in the story). It is no fun waiting for test results, I am learning, no matter how routine it becomes to get needles stabbed in one’s neck. It is no fun getting needles stabbed in one’s neck either. But the very worst is waiting on test results when one is reading a novel that isn’t very good.

I was reading that not very good novel yesterday when I wasn’t waiting for test results, and while the novel wasn’t good, reading it wasn’t so bad. But once I’d had the tests and things got heightened, I started to feel resentful.

We turn to books for certain things–for entertainment, for wisdom, to pass the time. Sometimes the right book comes along and offers all the answers that infinite existential google searches might fail to turn up. But to need some such thing and find yourself instead in the hands of an author whose book is carelessly constructed, sloppy, superficial, thoughtless. I don’t have time for that. The amount of understanding I’m willing to extend as a reader shrinks to about none.

When my world seems unsteady, I don’t want to read for escape. Instead, I require literary foundations solid and deep, something sure beneath my feet.

Is it too much to want a book to capture my attention, and also save my life? Anything less is just bookish jetsam.

Anyway, if you need me, I’ll be reading the new Lorrie Moore.

March 2, 2014

The Mystery Shopping Cart by Anita Lahey

It’s about once or twice a day when something happens that reminds me how much I’m going to miss Book City when it’s gone (which is not too long now–stock is down to 40% off and the shelves are bare). I’m going to miss having a shop just around the corner that I could quite sure would have a copy of The Mystery Shopping Cart: Essays on Poetry and Criticism by Anita Lahey in stock. In fact, they had two. To think I took this for granted for awhile, being served as a member of the public who just happened to require The Mystery Shopping Cart at a moment’s notice.

It’s about once or twice a day when something happens that reminds me how much I’m going to miss Book City when it’s gone (which is not too long now–stock is down to 40% off and the shelves are bare). I’m going to miss having a shop just around the corner that I could quite sure would have a copy of The Mystery Shopping Cart: Essays on Poetry and Criticism by Anita Lahey in stock. In fact, they had two. To think I took this for granted for awhile, being served as a member of the public who just happened to require The Mystery Shopping Cart at a moment’s notice.

And the reason that I required the book was because I was developing this fantasy in which I published a series of books of literary essays and reviews by Canadian women critics (including myself, naturally). I find that women writers in particular tend to be a bit all over the shop in terms of oeuvre, and I think that something magical might happen when you curate their non-fiction into a book, and some kind of overarching narrative emerges, their preoccupations become apparent, the approach that was always always there, but it’s just that she didn’t feel the need to state it in boldface over and over again.

This fantasy came about because I kept noticing the way in which male critics tend to get their work collected into books in numbers which, compared to female critics, reflects how much more of their criticism is published in the first place. And then I discovered The Mystery Shopping Cart, the book of my dreams. To Book City I ventured then in order to hold that dream in my hand.

Last week I stated (on twitter, no less) that The Mystery Shopping Cart was a perfect antidote to February, as well as to bookstore closures and general dissatisfaction with the state of the world. Because here is a book that testifies that words, books and ideas matter. Here is a smart and generous voice that takes the reader into its fold. The book begins with friendship, Lahey’s with poet Diana Brebner, and I didn’t manage to get through the first piece about Brebner (and how a mysterious shopping cart had once found its way, overturned, onto Anita Lahey’s lawn) before putting one of Brebner’s books on hold at the library–the one with her Mary Pratt poems.

This is that kind of book, the kind that takes you places. The kind with essays about poetry that I read anyway, though I am not a poet myself, or a confident reader of them. These are essays about poets I’ve never heard of, poets that I’ve never read, and I read these essays anyway. They presume that I should care about these things, invite me to do so, and I do. I am welcomed into the conversation, rather than alienated from it (by jargon, theory, grudges and biases I’m not privy to). Last week, for the first time I reviewed a poetry collection and felt confident about what I’d written, certainly not least of all because I was writing under Lahey’s influence. From The Mystery Shopping Cart, I’m learning that poetry might be mine to think about and write about, that I don’t necessarily need to learn a whole other language in order to do so, and just because poetry sometimes leaves me puzzled doesn’t mean I’m reading wrong, and that puzzlement (and a willingness to be made so vulnerable) is sometimes the very point.

Much of this book was familiar to me from Lahey’s associations with The New Quarterly. It was a pleasure to once again encounter her interview with Sharon McCartney and Kerry Ryan about poetry and boxing/wrestling/kickboxing, as well as her conversation with Kim Jernigan and Alice Munro. I’d also read some of her reflections from Arc Poetry Magazine in the wonderful Quarc Issue (which I adored and wrote about in 2011).

I enjoyed her essays about poets familiar to me (PK Page and Gwendolyn MacEwen, and how she takes issue with the former for inspiring a generation of Canadian poets to write terrible glosssas, and with the rest of us with conflating the self and work of the latter) and others–Dorothy Roberts, exiled Canadian and niece of Charles G.D.–who knew? I also appreciated her conversation with poets Stephanie Bolster and John Barton about the lure of ekphrasis. And how Lahey’s critic work is complemented by the personal essay included at the end.

The whole book was so good that it makes me fantasize about my female critics series more than ever. Sometimes I fear that in spending so much time lamenting the voices that are missing that we’re neglecting to pay attention to the few that are there. Kudos for Palimpsest Press for making this reader pay attention.

February 28, 2014

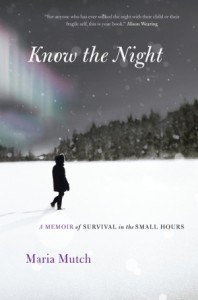

Review in The National Post: Know the Night

I reviewed Know the Night: A Memoir of Survival in the Small Hours by Maria Mutch in the National Post, and writing the piece was like building something out of materials which are more exquisite than anything I’ve ever worked with. The book is weird, wonderful and enthralling, and to call it a memoir about parenting or autism is to reduce the book to something finite, which it isn’t. The book is bigger than all of that–it’s about books, jazz, lists, loneliness, the whole world, and it’s a love story too.

I reviewed Know the Night: A Memoir of Survival in the Small Hours by Maria Mutch in the National Post, and writing the piece was like building something out of materials which are more exquisite than anything I’ve ever worked with. The book is weird, wonderful and enthralling, and to call it a memoir about parenting or autism is to reduce the book to something finite, which it isn’t. The book is bigger than all of that–it’s about books, jazz, lists, loneliness, the whole world, and it’s a love story too.

‘”There is nothing quite like caring for a child alone, while the rest of the world is sleeping. In the dark, reality loses its shape, time slows as the clock ticks towards sunrise. It is easy to become unhinged. In her first book, Know the Night, Maria Mutch documents her own experiences during what she calls “the small hours.” For two years her oldest son, Gabriel, slept very little. She was either up caring for him, or, anticipating he would soon awaken, be unable to sleep herself. It was an arrangement Mutch calls a product of “parenting’s alchemical gist: the love for the child … mitigates everything else; what would seem anathema to others becomes … the status quo.'”