January 25, 2024

The Writing is the Point

I texted my husband a few months ago with an idea I had for a new novel. He replied with a comment about how he was excited that I was excited about writing something new. “I bet you are, ha ha,” I wrote back, because he’d been the one to console me through my months of post-publication ennui, but he affirmed that he really meant it, because he knows that writing is a thing I do, even if it’s not a wise thing, and certainly not a financially lucrative thing, even if publication itself is not a destination that delivers me much in the way of satisfaction and contentment. And that is why I love him, and this is what love is, I think, someone who gives you permission to make bad choices that are the right choices, because even though they might know better, they also understand.

Towards the end of December, I was feeling paralyzed creatively, any confidence I’d felt in my abilities and expertise totally zapped by how hard it had been to publish my latest novel. I felt like a fraud. It was painful, and dispiriting, and I’m so grateful for the long break I took over the holidays, to retreat from the FOMO of the online world and take solace in actual real life people (to quote a certain Anna) and a huge pile of books, to feel my soul grow back, and begin to feel creative and inspired again.

In 2021, I hadn’t been without a project in years. I started Mitzi Bytes in 2014, I started Asking for a Friend in 2015, published Mitzi Bytes in 2017, and started Waiting for a Star to Fall in 2018. That makes for almost a decade with something creative waiting in my back pocket, an easy answer to the question, are you working on something new? Plus there was a global pandemic still going on and, though I didn’t know it at the time, I was well on my way to a mental health crisis that was going to break my brain, so it’s not so surprising that I was having some trouble thinking up a new idea for a book.

Somehow I broke through that pressure, however, and started writing a novel about a woman who has just left (exploded) her marriage and who begins a new life in a Toronto rooming house, a novel about a character I’d envisioned as a modern day Barbara Pym heroine. I had a framework for the novel, 12 chapters, each one taking place over a month, the entire novel the course of a year. The trouble started, however, when I’d reached 70,000 words and wasn’t even six months in, plus the problem of there being no plot. So I abandoned that project, and decided I would write a thriller, but then that fell apart, and then I fell apart. Speaking of paralyzed.

Imagine my surprise, however, when I reread the modern-day Pym book a year later…and realized it was really good? (It was really good because, though my crippling self-doubt of last fall would tell me otherwise, I’ve figured out a thing or two about writing novels, and also because I started writing it under the influence of Katherine Heiny, whose work has taught essential things about enlivening fiction and highlighting the absurdity of everyday life). I decided to abandon the 12 chapter framework, broke the chapters down into smaller pieces, conceded that a literary arc could be possible in a six month period, and just fell deeper and deeper in love with Clemence Lathbury and her world.

Last year I set to revising the manuscript, in between edits and revisions on Asking for a Friend, preparing for that book’s publication, and working with manuscript consultation clients…and I didn’t get much done. Something was missing, and I didn’t know what it was. I didn’t have the focus. Maybe there’d been nothing there there after all? But the bits of dabbling I was doing over the fall suggested otherwise. At the end of December, as I recovered from a difficult season and prepared to start creating again—remember, I had this idea for another new novel, this one a family saga—I set a goal of first getting Clemence’s story into fighting form by the end of January, if such a thing was even possible. Was it possible?

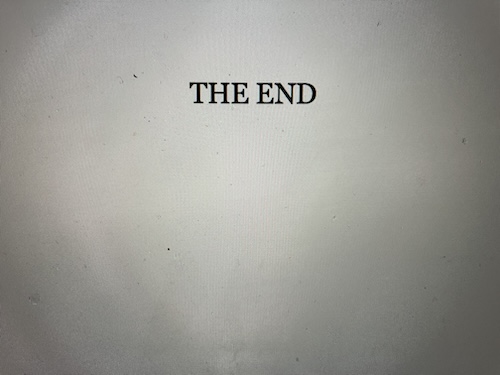

But reader, I did it! Yesterday I added the final link in the thread that had been missing from my narrative, and today I read the final chapter and the epilogue, and was just absolutely dazzled by the ending, which I’d forgotten altogether, and I was properly impressed with myself for pulling it off. I begin working with manuscript consultation clients for the next two months, but will commit to a read-through in April, after which point I will likely (!) send it off to my agent. The prospect of which terrifies me to no end, because while I think that my agent will like it, and that it’s the best book I’ve ever written (so fun! so smart! so full of humour and light!) I’m also the author of three poor-selling novels, which is not a stellar track record, and the deeper on gets on that path, the harder it becomes to change course. Sigh.

But right now, I’m choosing not to focus on that, instead to celebrate my win of getting to this finish light, amidst global crises, and mental health breakdowns: I have written another novel and I really really love it. I am also having fun putting together my new newsletter, and I’m recording the first interview for my new podcast tomorrow! And at some point in the next few months, I’m going to start writing that family saga, and maybe I won’t be able to pull it off, and maybe no one’s going to want to publish it even if I do, a challenge I’ll face if and when it arrives, but in the meantime I will do what I do, which is write, because I love to write, because the writing is the point.

January 23, 2024

Gleanings

- But once the pianist played our opening and we assumed our positions, then began to move in formation as a real corps de ballet, I stopped thinking about how I might be perceived. Instead, I smiled, breathed in, imagined the top of my head reaching toward the ceiling and let my body present the movements it had been perfecting all week. I stopped judging my every bodily infelicity, quieted any fears and just danced, suspended in time.

- And so yeah, I love my own books, and I want them to be successful but I just…cannot get very fussed about it. Mainly…every now and then I’m still fussed. But really–just what are the odds! If you have seen what I’ve seen–which is actually NOT all the books published in the English-speaking world in a year, but a fair percentage of them–you just can’t get that upset anymore. You still work hard–I still work hard–but like Le Petit Prince on his tiny planet (why are so many things like Le Petit Prince to me?)…it’s an odd perspective

- A middle-aged woman being a life coach is a laughingstock. I know it. We all know it. (I’m Not Sorry About Being a Coach)

- So here I am, feeling a bit shaky like James, falling into your arms. My dad has dementia. It is terrible and often beautiful in totally surprising ways. I’d like to write more about it here. I hope that will be as healing for some of you as I know it probably will be for me.

- I am from the hot desert sand, from where palm trees sway/ Heavy with fresh, golden dates hanging just out of reach./ I am from mudpies, made outside while parents napped./ And the sun beat down on our bare, unprotected brown skin.

- This book of mine pays tribute to poets adults read—Elizabeth Bishop, Emily Dickinson, Mary Oliver—but also to Margaret Wise Brown. You are never too young for the rapture of language—or too old to let it take you somewhere entirely new.

- This is going to sound so trite, so petty, but…I actually feel bad for them. What a sad little world they’ve created, where perfection is the thing that matters. Where the ability to Control your Human-ness is rewarded. To earn your spot here, you must be able to push down your fear, your flaws, your idiosyncrasies, your pain, your personality. Please be a machine, with just the right amount of “musicality.”

- My lobster is out there. Who knows, I may have already met him. But, rest assured, I haven’t waited this long, or done the inner work or, frankly, endured the experiences I have to be disappointed. My person is out there, just waiting for me to make space for them in my life and in my heart.

- You are the original Teflon. You sear meat, reduce a sauce, sweat an onion, and yes, dear cast iron pan, you’ll fry my morning egg.

- In moments like these I start to doubt even “reasonable hope.” I have to admit it. When you see such horror and unjust actions. And, yet, part of me believes that we cannot move forward without some element of hope. What is reasonable hope at the moment? Very difficult to describe. But I communicate with Palestinian and Jewish friends of good will. Notwithstanding the context, they give me hope. Notwithstanding the tears they shed and the sorrow they go through, I can feel hope in their words. I hope I am being reasonable!

- My bridge tales come directly from my heart and my imagination. I just hope I have the fortitude and competence to get this project across the finish line which, for me, would be taking it to the printer.

- I’m glad to have a place to hang up my hat, both literally and figuratively.

- But what I’m wondering, these days, is how to model the behaviour of reading more? In the summer, I’m going to try and read more in public spaces and on park benches. Maybe until then I’ll read in cafes and in libraries.

- When you’re the one who doesn’t leave … you always wonder – what it would be like if you left? Wonder what it would be like if you were elsewhere. Especially when you were the teenager who couldn’t wait to get outta this place …

- I’m really proud of my day, of the feelings of achievement I have for resting, the creativity seeping through as cracks start to appear in the bed of tight, tense perfectionism.

- i can get really tired of people thinking i’m odd. i’m only as odd as the next guy. and i’m not talking about the naked guy at the beach. It gets old, and being embarassed is not that good a feeling, it seems to ride side-saddle to shame.

January 22, 2024

Taking Stock for January

Getting: Ready to start booking summer camping trips, which is my favourite winter vice. (Ontario Parks reservations open up five months in advance!)

Cooking: Soup, soup, always soup. The chicken dumpling soup in Smitten Kitchen’s Keepers is a life changer!

Sipping: WATER. Water that’s not infused with tea, because water is one of my New Year’s Resolutions, in terms of ingesting and marinating in via frequent visits to a steam room.

Reading: Interesting Facts About Space, by Emily Austin, and just as wonderful as I’d hoped as a follow-up to Everyone In This Room Will Someday Be Dead.

Thinking: About the person who tried to shame me on Friday for LIKING and then UNLIKING her Facebook post (even though I did like it, and explained as much, but I had pressed LIKE and immediately felt a sense of dismay at the gamification of my feelings AND then the whole ensuing fallout really underlined that my instinct to disengage was quite correct in the first place.

Remembering: to experience the moment/season I’m in right now rather than rushing to the next one

Looking: at the snowy powder on the porch outside. I don’t hate it!

Listening: to the Kara Swisher podcast conversation with Heather Cox Richardson. Why can’t I stop listening to US politics podcasts? I don’t know!

Wishing: The US politics was boring.

Enjoying: The slowness of January as we ease into the new year

Appreciating: Any time the sun shines and the sky is blue

Wanting: More opportunities to promote my novel this spring.

Eating: A McVities digestive biscuit! (Plain, not chocolate)

Finishing: The first essay in my new substack, which will make its debut next week! It’s about re-reading Danielle Steele after 30 years!

Liking: Spending less time on social media and improving my focus by writing long form

Loving: Taking more time in the whirlpool and steam room at my gym.

Buying: A new winter hat! (It’s so good!)

Watching: I introduced my kids to the 1990s movie MERMAIDS starring Cher, Winona Ryder, and Christina Ricci last weekend, and (to my great joy!) they loved it (and it really did hold up!)

Hoping: To be able to keep my January sense of chill as life begins to speed up again.

Wearing: A cardigan, OBVIOUSLY. Because I am a human person with arms and it’s January.

Walking: Carefully on the slippery sidewalk

Following: the trajectory of my 10-year-old’s illness (which is the first time either of my kids have been sick this school year. We’re pretty lucky!)

Noticing: The light lasting longer every day

Saving: A packet of Mini-Eggs that I bought right after Christmas on sale. My daughter asked me if I’d forgotten we had them. I haven’t forgotten. I just like having them.

Bookmarking: Every piece in TNQ’s Writing In/During Crisis series. Have you read them? You should.

Feeling: Good!

Hearing: The mysterious babble of my very noisy 15-year-old fridge.

January 22, 2024

A History of Burning, by Janika Oza

While A History of Burning arrived in my mailbox months ago, it’s taken me some time to finally get to it, because it’s a big book, in terms of scope and word count, and the literary autumn is always overwhelming, and so I’ve been glad for the slowing-down-ness of January and the chance to finally get to dig in to this book that’s garnered so many accolades from writers I admire, plus an honoured spot among finalists for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction.

Spanning almost 100 years, the novel begins with Pirbhai, aged 13 in 1898, tricked into leaving his mother and sisters and boarding a boat for Kenya where he spends the next few years as an indentured worker building a railway for the British. Eventually he marries Sonal, another Indian in Kenya, and together they set off for Uganda in pursuit of a better life, which they achieve, and their son, Vinod, grows up happy and hale. He has dreams of pursuing a university education, but his parents don’t have the means for that, and so he does the best he can with his marriage to Rajni, who doesn’t want to marry a stranger, but Karachi in 1947 is dangerous, and Rajni’s parents feel she’ll be safer in Uganda, so she goes, and the two build a life upon the foundation of Pirbhai and Sonal’s big dreams for life and prosperity, though it’s not long before their world is disrupted by Uganda’s independence, a movement embraced by the Vinod and Rajni’s spirited eldest daughter, Latika. And in 1972, as Asians are expelled from Uganda under the brutal tyranny of Idi Amin, the family loses everything, forced to begin all over again in a new life in Toronto.

The narrative moves between these family members, as well as others, to paint an ambitiously broad picture of this family’s story, the exiles they’re forced into together and apart. And while there were moments I wished the story had drilled down deeper into specific characters’ experiences, the story’s broadness and grand sweep were necessary to show the ways in which the same patterns of loss, heartache and exile recur so many times over a century, the unrelenting violence of colonialism and its echoes. The many ways too in which human beings are able to other their neighbours, regard them as inferior, fall under the spell of autocracy. Such gorgeous writing: “They held their voices low, because they knew: how a dictator’s word becomes the world, how he bends reality before him, how it was not the facts that would determine their lives, but the whispers, the rumours spilling between.”

January 19, 2024

Who’s That Girl?, by Mhairi McFarlane

“The Midlands were in-between, just like she was, and the landscape, flat and unassuming, suited her needs. Low and soft, just like a heath, an ideal place for her to land.” —Asking for a Friend

I didn’t know how much it would mean to me to open the pages Mhairi McFarlane’s Who’s That Girl? and be transported back to the city of Nottingham. I haven’t been this excited to be back since I first read Saturday Night, and Sunday Morning, except back then it had only been a handful years since I’d lived there, and now it’s been more than 20. More than 20 years since the last time I walked down Mansfield Road, and then up Sherwood Rise on my way to my little house in Basford. More than 20 years since I’ve been to a Goose Fair, visited the Old Trip to Jerusalem Pub, or contemplated the spiritual distance between West Bridgford and The Meadows. 20 years ago, there wasn’t a burger joint in The Lace Market, but I was so excited when McFarlane’s protagonist, Edie, goes to The Broadway. Her best friend gets divorced and moves into a depressing bachelor pad in Sneinton. She hangs out at the Arboretum. A picnic at Wollaton Hall! I was only disappointed that she doesn’t actually realize her dream of finding ducks to feed on her birthday, because I was very into ducks when I lived in Nottingham, and she wouldn’t have had to search so far to find some.

That, for very personal reasons, I was captivated by this novel about a young woman who slinks into Nottinghamshire with her whole life in shambles (Edie has just attended her work colleagues’ wedding in Harrogate [it becomes Harrogate-gate] and been caught snogging the groom, even though the groom was snogging her, but no matter, she’s on the verge of losing her job as well as her social standing, and her only chance at redemption is coming back to her hometown and ghostwriting the autobiography of a pampered movie star, who is also a Nottingham native) doesn’t mean that this isn’t a story that anyone might enjoy. This is the third novel I’ve read by McFarlane, and I think I love her. She writes romance in which the romance itself takes a backseat to complicated and difficult stories of living through and overcoming trauma, complete with vivid characterization and sparkling humour.

PS A McFarlane has just announced that a sequel to Who’s That Girl? is coming out this year!

January 18, 2024

CNOY 2024 in support of the Fort York Food Bank!

It’s cold out there, and so many people need support more than ever. This will be my third year participating in the Coldest Night of the Year fundraiser in support of my neighbours at the Fort York Food Bank and I hope you will support me. If you’re local, consider joining my Harbord Village North team and walking with us on February 24. If you can’t make it or if you’re further afield, please consider making a donation here.

The food bank has set an ambitious goal of raising $200,000, reflecting the fact that they’re receiving more clients than ever before, currently more than 4600 a week. The Fort York Food Bank are doing essential work these days and I’m grateful for an opportunity to help.

January 17, 2024

Off the Record, edited by John Metcalf

I’ve written before about my aversion to self-mythologizing male writers, how much space such hot air takes up in so many rooms, a logical counter, of course, being more women encouraged to see themselves as subjects of grand narratives, to tell their own stories in their own voices, and so enter Off the Record, an anthology of essay-interviews with six writers who’ve worked with editor John Metcalf over the years. Metcalf continuing the editor’s work of self-effacement in this volume, his questions removed from the interviews so just the writers’ voices remain, each interview telling the story of one writer’s becoming, followed by a short story by the writer in question, the fiction as a kind of arrival.

Keep your pencil handy, for this is an underlining, notes (and hearts) in the margins kind of book, with highlights like this from Kristyn Dunnion: “Good writing often embodies a numinous quality, sifting through echoes of other lives lived, connecting clues in an attempt to find meaning: ghost hunting.” Dunnion, along with Elise Levine, two of the writers included here whose work I’m not familiar with, but I appreciated their pieces just as much as those by Caroline Adderson, Cynthia Flood, Shaena Lambert, and Kathy Page, all of whom have written books I’ve loved. The ways in which each of their journeys have been different, but the commonalities too (quite a few backgrounds in activism informing the imagining of fictional worlds). Complicated relationships with parents, publishing journeys that affirm something my friend Marissa Stapley shared not long ago, about a writing career as a marathon, not a sprint, rife with as many downs as ups. The publishing business has always been fraught, and a book deal has never been the end of the story, but maybe we’d be sorry if it was.

From Shena Lambert: “Showing makes our worlds more believable. But this is a secular way of understanding what is actually more like a magical question. In fiction, anytime you press into the five senses, you will write something specific, something, precisely because of its singularity, which will begin the strange work of making meaning. Things of the earth want to be doors into something greater.”

THINGS OF THE EARTH WANT TO BE DOORS INTO SOMETHING GREATER. I don’t know a better explanation of fiction-making, which is to say meaning making, than that.

January 15, 2024

Gleanings

Special edition of “Gleanings” with pieces from The New Quarterly’s stunning “Dispatches: Writing In/During Crisis.” I’m so grateful to TNQ and all the writers who contributed.

- You don’t need to know the answers. Writing is driven by questions. Readers want to see you stumble toward truth. I give them permission to be uncertain, to search, to fail. Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart, I tell them, quoting Rilke. Live the questions now.

- End this war. As the great soul Vivian Silver, murdered so brutally by Hamas, told her beloved Palestinian and Israeli friends: There is no road to peace. Peace is the road.

- With the intensity of the ruination it has created and continues to create in Gaza, Israel seems to have ambitions to destroy our ability to imagine at all. As a writer, I felt particularly attuned to it.

- This language—the power it carries—cleaves me. I think to myself, naively, that if the world understood the beauty of this moment without the blunting, the thinning translation into English for it to be understood, this earth-shattering moment in Arabic, they might care about this girl, and this man who saves her from the death she thinks she’s experiencing. I think about how journalistic language describing Palestinian men and girls like them is rarely this beautiful, this tender, this poetic. Western audiences never see this beauty because not only do we reduce and censor the language we use about Palestinians, we can barely even speak about them at all.

- Was it possible to be blameless and innocent? What would it mean to create a house with “no more padding between the word and the world”?

- I believe that it is my particular obligation as a Jewish writer and one who has written about persecution and genocide to speak out about this. I know that many in my (Jewish and other) community will be angry and upset with me. That they will be horrified that I don’t centre the hostages and the loss experienced on October 7th. It’s not that I don’t understand the pain or want those humans returned to safety. Or that I support Hamas or don’t wish for a different political leadership and solution in Gaza. It’s that I believe the horrifying events happening there meet the definition of genocide. We’re in the middle of a genocide. Never again.

- To choose to embrace suffering, whether in experiencing or witnessing it, though our fears may tell us we’re unequipped to handle that. To choose not to stay trapped within the suffocating boundaries of comfort, though our fears may tell us they’re the only thing keeping us safe. Perhaps most of all, to embrace our inherent wildness, the endless contradictions and complexities of ourselves and others, though our fears may tell us that will leave us unmoored without the ballast of simpler, easier moralities./ Only then, perhaps, can we say we’re truly alive. The words come unbidden after that.

January 15, 2024

One-On-One

Yesterday I sat on my couch beside a friend who scrolled and scrolled through the vacation photos on her phone, two weeks in Japan, and it occurred to me that I can’t remember the last time I partook in such an activity, and also how much it fulfilled me. How different it felt to see her trip and hear her stories, rather than just aimlessly scrolling through them on my own social media feeds, how such a thing stands for everything I’m yearning for right now, one-on-one contact, live and in person. I have found existing so much on a virtual realm overwhelming and confusing as I try to make sense of my connections to others, what’s required of me, and what I should expect in return. I am having the unsurprising revelation that maybe human beings are not meant to have 3700 friends—who knew? So going back to basics, and grateful for the ability to share meals together, visit in our homes, have conversations over tea and coffee, all those things that until 2020, it never would have occurred to me to take for granted. And how completely they can fill my soul.

January 11, 2024

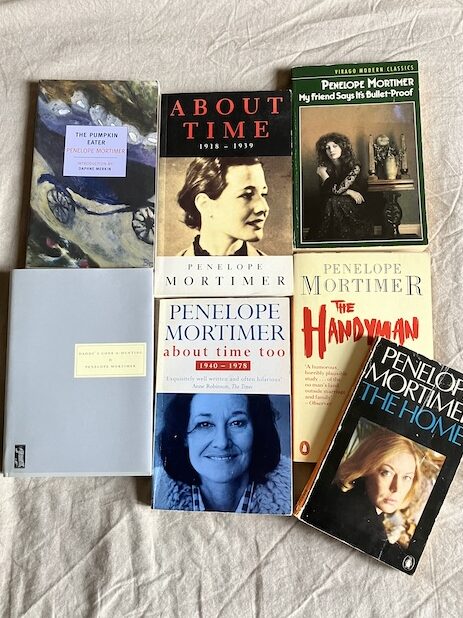

Penelope Mortimer: About Time (Too)

“Of all the Penelopes, Mortimer is my favourite,” I wrote in 2018, though I don’t think I’ve read her since then, and need to refresh my memory, especially now that I’ve just read her two memoirs, ABOUT TIME and ABOUT TIME, TOO. Penelope Mortimer is a standout in my library for being the only author whose books I own in editions from Virago Modern Classics, Persephone AND NYRB (plus two regular old orange-spined Penguins, even though THE HANDYMAN has fallen to pieces). I first learned about her from Carol Shields’ and Blanche Howard’s collected letters, in which they raved about THE HOME, which I loved so much. I actually have no recollection of reading DADDY’S GONE A_HUNTING, a 1958 novel about a mother procuring an abortion for her daughter. I took THE PUMPKIN-EATER, perhaps her best-known book, on a beach side holiday about ten years ago and found it wholly unsatisfying for the occasion, but I think I will appreciate it better now having read its author’s memoirs, for this novel—like all of her novels—was borne of her experience, and that context might just be essential.

In ABOUT TIME, TOO, she writes about looking back on her childhood as a kind of Eden, though it doesn’t read like that me in her first memoir, instead a middle-class English experience of sexual abuse and emotional deprivation, but she recounts it all so jollily that one might just be convinced. The second paragraph of ABOUT TIME begins, “Fortunately I know nothing about my ancestors, and see no particular reason to find out,” and I actually LOVE that, but it’s also emblematic of Mortimer’s refusal to engage with the heart of things, even if such refusal is why the memoir is a pleasure to encounter. The pain in ABOUT TIME, TOO is much more visceral, immediate (a lot of the book is taken from Mortimer’s journals), mostly surrounding the breakdown of her marriage to playwright John Mortimer, her second husband. In between the two husbands, she had two children with two more different fathers, having six children in total, and between the lines one might read some regret about how her children might have suffered by their parents’ unconventional choices, but not too much, and I admire the way Mortimer never apologizes for her sexual appetites, or for her creative impulses, her need to be writing and creating. “The only way to love it all is to cling to it too fiercely. I don’t want to let anything else, anyone else, in. My comfort is the idea of writing this novel. My aim is to keep alive.”