November 27, 2014

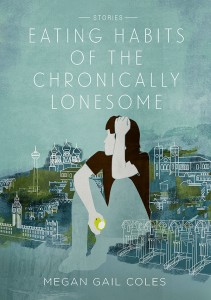

Eating Habits of the Chronically Lonesome by Megan Gail Coles

My reading rut from last week was successfully defeated by the books I picked up at the Toronto Book Fair, in particular Megan Gail Coles’ Eating Habits of the Chronically Lonesome, which was the book I bought because I kept seeing other people walking around carrying it. In some crowds, such a method of book selection could steer one wrong, but not in this one. The book was fantastic, a collection of short stories about Newfoundlanders at home and away. The characters in the stories have lives that are linked, but the connections are loose, and stories take place across a long period of time, so that the connections vaguely inform one another rather than being integral to the collections’ construction. They do give a wonderful sense of these characters’ lives off the page being rich and ongoing, the stories themselves just standing in for a moment in time.

My reading rut from last week was successfully defeated by the books I picked up at the Toronto Book Fair, in particular Megan Gail Coles’ Eating Habits of the Chronically Lonesome, which was the book I bought because I kept seeing other people walking around carrying it. In some crowds, such a method of book selection could steer one wrong, but not in this one. The book was fantastic, a collection of short stories about Newfoundlanders at home and away. The characters in the stories have lives that are linked, but the connections are loose, and stories take place across a long period of time, so that the connections vaguely inform one another rather than being integral to the collections’ construction. They do give a wonderful sense of these characters’ lives off the page being rich and ongoing, the stories themselves just standing in for a moment in time.

Coles, whose background is in theatre and playwriting, is the real thing. Deft with prose, gifted with voices, writing from a wry, wise and empathetic perspective, she is undoubtedly part of the established tradition of fine Newfound short story-writing.

In “There are Tears in This Coconut”, two fractious sisters take a trip together to Thailand following the eldest’s divorce, a lifetime of resentment and anger acted out on the part of each of them.

“Everyone Starves to Death As I Eat Here” begins with the shining line, “Damon thinks, this, everything, is Brenda Hann’s fault for making him believe her pussy was made of gold.”

And then a few pages after, “The reason Garry did these things was ’cause he couldn’t afford any better. Half of what he earned over at Pretty Paws was carted off to Newfoundland. Child support for an autistic kid he had with Slutty Marie down Gilbert Street, this the result of a one night stand./ Have you ever heard a sadder story, Dame? I mean, really? I barely poked her. We weren’t even lying down. It’s like her body sucked me sperm right inside her that night, vacuum cunt on her. Don’t ever have a go at the neighbourhood whore in an alley. Nothing good will come of it.”

And then in the next story, Nigerian immigrant to Newfoundland working at Tim Hortons woos a local woman and thinks his life is made, the story ending on the suggestion that this is perhaps not the case. Time telescopes in “A Sink Built for Small People,” which is next, in which a couple moves to Korea to teach English and their relationship (predictably) falls apart. A new mother laments what’s become of her life in “I Will Hate Everything, Later.”

A widower wonders about his shaky domestic life with a new partner: “I think washing up the supper dishes shows I care. I always flushes the toilet three times. And I knows that’s more than Father ever did. She says that’s gross. Not like in her books. That my love is vulgar. Not refined. Not civilized. I’m rural in my heart. She plans the birthday party she’d like. I does the same. We always ends up with the wrong birthday party. And we aren’t young.” We always ends up with the wrong birthday party—isn’t that some kind of amazing definition of a tragedy?

A woman navigates the terrain of a new life, after breaking up with the man she’d thrown away her twenties on in “This Empty House is Full of Furniture.” Another contemplates the circumstances that led her to homelessness and vagrancy in “French Kissing is For Teenagers.” “Single Gals Need All Wheel Drive” is one of the best stories I’ve ever read about a character with cancer. A Haitian immigrant to Montreal plots a future with her dodgy landlord in “There’s a Fish Hook In your Lip.” “Ultimatums Grow In This Wild Place” returns us to first story, this one written from the perspective of the divorced sister’s ex as he prepares to end their marriage (and have her finally face the fact that he’s gay).

And then “A Dog is Not a Baby”, which is simply the thoughts going through a an elderly mother/grandmother’s mind as she waits for the phone to ring, for one of her children or grandchildren to call: “If she starts thinking on how the phone never rings now, she won’t be able to be conversational when it finally does. Instead, she’ll respond with a series of grunts. Maybe make an off-handed remark on how she might as well be dead. Tiffany will feel guilty, her mother Margaret won’t even notice, and Joss will say, it’s a wonder anyone calls her at all. / What would anyone want to call you for? You never got anything pleasant to say sure.”

The stories in “Eating Habits of the Chronically Lonesome” are also linked by references to food, to hunger and indulgence, flimsy plastic forks and years ago when spinach was rare. Vivid, mordant and moving, they’re about connection and disconnections, and the ways in which we hurt and heal ourselves, and each other.

November 26, 2014

Let’s all dance with Julie Flett

I am so pleased with, proud of, and excited by my 49th Shelf interview with the brilliantly talent illustrator, Julie Flett, who is behind the images in a few of our family’s most beloved picture books (including Little You, which I’ve written about before). The post is gorgeous, first because it’s packed with Flett’s beautiful illustrations and book covers, but also because her responses to my questions are so fresh and thoughtful, with so many excellent book recommendations. Plus, we talk about holey socks, wallpaper patterns, big suns, and all the exciting things happening in First Nations Children’s Literature in Canada today. It’s so good.

November 24, 2014

On Mentors

Recent news had me thinking about mentors, how we imagine that success comes from kneeling at the feet of wise professorial men, or at least job opportunities from a date with a charismatic celebrity. What about women mentors though, I wondered? I started asking other writers about their own women mentors, and it turned out that these kind of relationships are not very common. For a few reasons, I think.

Recent news had me thinking about mentors, how we imagine that success comes from kneeling at the feet of wise professorial men, or at least job opportunities from a date with a charismatic celebrity. What about women mentors though, I wondered? I started asking other writers about their own women mentors, and it turned out that these kind of relationships are not very common. For a few reasons, I think.

First, that there are fewer women in positions of power to serve as mentors. Second, that women are often already stretched with other caring commitments. Third, that perhaps we all know that mentorships will never make or break a writer’s career—her work and talent matter, and probably best to focus on that. And finally, because of the realities of women’s lives (dearth of time, power, money, etc), mentorships have taken on less traditional structures, are often virtual, and perhaps aren’t always recognizable for what they are.

Certainly, I’ve never knelt at the feet of the women who’ve served as mentors to me, some of whom I’ve only met in person once or twice. I think of Sheree Fitch, who never ceases to champion other women writers’ work, a vocal supporter of my blog and my book for so many years; Michele Landsberg, whom I encountered in the comments of my blog and we bonded over mutual admiration for Joan Bodger, who has been so supportive of my work; Rona Maynard, who has been a huge influence as I’ve put the pieces of my career together over the last decade and tried to take it all more seriously; Marita Dachsel, who helped me navigate my early days as a mother/writer; Tabatha Southey, who rocks it every week in the Saturday Globe and exists to make us all aspire to be smarter (and funnier); and my friend, Anakana Schofield, who sends me emails that say (and I’m paraphrasing), “Stop talking about mentors already, and just write your fecking book.”

Oh, the women I have in my corner. They’re everything. Not least of all my friends, plus contacts in The Toronto Women Writers Salon, and CWILA. This is all turning into a protracted version of my Linked In profile, which is beside the point, which is to say that supportive women are everywhere. You only have to look, and also to celebrate, and be inspired too to serve a similar role for younger women whose work you admire.

*****

I asked some other women to tell me about their own mentors, and am pleased to be able to share their responses.

**

In the mid-eighties, I set up a meeting with Karen Mulhallen, hoping to volunteer for Descant magazine. I knew nothing about anything. About an hour later, I left her house as managing editor. Karen became a mentor, an ally and a dear friend, doling out challenges in a way that seemed offhand but was somehow impossible to refuse. Over the years she has continued to put me in the way of writing and editing opportunities I would never have tackled had it not been for her confidence in me—or her willingness to take a leap of faith. I suspect I’m not alone in saying this about Karen. She is a truly generous person, in both life and art.

**

When the phone rang at Berton House in Dawson City, Yukon four years ago, I never imagined it would be my Can-Hist hero – and a future mentor. But on the other end of the line, there was the crisp English accent of renowned biographer and historian Charlotte Gray, congratulating me on my successful Skype-in to the fundraising gala in Toronto. I had fan-girled her in my live interview, talking about how I had slid my book next to hers on the alumni bookshelf and was trying to soak in the genius left behind by her, Pierre Berton, and others. Since then, we have crossed paths in person only twice, but she has written me letters of recommendation, we have tweeted about her “academic ninja-ness” on Canada Reads, and she even made me her junior “running mate” in a literary award competition. Those votes of confidence have spurred me on through the inevitable crises of confidence and the exhaustion of juggling a small child and a writing career. I’m so glad I picked up that phone.

So I took her advice.

Eventually I got to study with Sarah’s mentor, Zsuzsi Gartner and the experience was challenging and enlightening and transformative.

Later, I returned to Sarah and thanks to her thoughtful direction, I was given the opportunity to work under the insightful and practical guidance of Annabel Lyon.

All my mentors have had helped shape me as a writer through developing style, building confidence, and trusting my voice. I am appreciative, grateful, and humbled and I continue to work under their influence.

This year, I am honoured to be a TA for Sarah’s online e-course where I have the opportunity to give back. And you bet I am giving away all the secrets I know, which, of course, are not secrets at all.

*****

I have been fortunate to have several great teachers—Priscila Uppal and Richard Teleky certainly helped chart my present course. But the woman I would call my mentor, who supported me beyond any professional obligation, is Susan Swan. She was my fiction professor at York, and subsequently supervised a directed reading course that allowed me to start my memoir. I dropped my first draft on her doorstep in four boxes: 776 pages. She sent emails by turns encouraging and devastating (I am loving this; it’s not going anywhere), and was unoffended by my request not to send any more before reading the whole thing. She did, and then invited me over. I always loved being at her home: it signified to me that writing was not incommensurate with a good and beautiful life. Those hours of discussion helped me to believe I had written something worth taking seriously. She gave the book to her daughter, the agent Samantha Haywood, whose representation has been an incredible gift. After its publication, Susan mentioned my book whenever there was opportunity—a deep kindness that helped me feel as though I was part of a literary community.

*****

Alas, I’ve not yet met American writer Susan Griffin face to face, but voice sounds and resounds inside me whenever I recall her our conversations. A year ago she was my editor but years before her book Woman and Nature, a poetic exploration of Western culture’s ideas of gender and nature, altered forever how I see the world and gave me language and the courage to dare to honour my own perceptions about woman as creators.

Susan became my editor at a time when I was in trouble with my novel, The Pig and the Soprano, the (true) story of a privileged Victorian woman who dared ambition on the Paris stage and ended her days as an impoverished recluse living with her pet pig. Susan worked as a midwife, giving me the sense that I had within me everything I needed to tell the story as it needed to be told and inspiring me to let the creative process unfold. Her written comments were insightful and catalytic and our phone conversations opened imaginative doors that set my spirits soaring. I’m forever grateful.

*****

I signed up for Colleague Circle for the free dinners. On the last Thursday of every month, eight of us—the six new humanities hires and two facilitators—gathered at the faculty club at 5:30 pm for insipid meals that consisted of a meat dish, a starch and an obligatory overcooked vegetable, followed by a creamy dessert. We ate, drank wine, debriefed about our first-year-faculty-member woes, compared grant notes, politely appreciated everything the University of Missouri offered us, and went our separate ways. I gravitated toward Maureen Stanton for her self-deprecating humor and her academic discipline: creative nonfiction writing. She had made a career for herself writing precisely the kind of prose I loved to read and found myself writing, yet not showing anybody—slices of life, creatively rendered. I hadn’t realized there was an institutionally accepted term for this. Timidly, I asked Maureen if she might share her course syllabus with me or provide me with a list of creative nonfiction classics. She responded with a generous reading list that I immediately began to work my way through with disturbing enthusiasm. Here I was at the university of Missouri, an assistant professor of Russian literature, and all I wanted to do was read literary nonfiction and acquaint myself with this new, yet strangely familiar genre. Maureen and I met for coffee and she shook her head as I regaled her with family story after story. “Why aren’t you writing this down?” she demanded to know. And that might have been the beginning. We later formed a writing group—her comments, the perfect combination of encouragement, awe, and incisive criticism—and she wrote letters of recommendation for me when I applied to artist colonies. “You’re a writer,” she told me after reading a short essay of mine, years before I ever dared to use that word to describe myself. I devoured all of her essays and read them closely, pencil in hand, as perfect lessons in craft. Her book, Killer Stuff and Tons of Money, is a riveting peek into the world of antiques and flea markets. In the end, we both left the University of Missouri (not at all on account of the awful Colleague Circle meals); she ended up teaching in Massachusetts, and I moved back to Toronto. Though I haven’t seen Maureen in eight years, she’s the first person I alert when I have a new publication out in the world.

*****

It’s damn difficult to name just one mentor. I’ve been so lucky: even in the deep bullshit of high school, there was Bev Hiller, my art teacher. She didn’t tell me that things were going to get better, she showed me how they could be. She treated us like adults and for that hour, we were. That classroom was an oasis.

Much later, after I’d already had two children and could only see the size of the canyon between me and the novel I wanted to write, I met Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer. I was writing journalism; it was as close as I could get to where I wanted to be. I was starting to think it was too late to start, that I’d never get there, that I’d blown my chance. But she had small children too, and she was doing it. She was fierce and committed and her generosity knew no bounds. She let me trail after her like a lost duckling at literary events. She kept nudging me by example and by suggestion. She has read almost everything I’ve written since then. My debut novel exists in no small part because she’s in my world. Merci beaucoup, Kathryn.

*****

My mentors are peers, women whose intelligence and generosity have encouraged me to work harder, write better, sometimes to write at all. Tending towards both vanity and insecurity, I depend on the bracing opinions of friends who won’t indulge either trait. Karen Connelly, Ann Shin, Camilla Gibb and Donna Bailey Nurse have all sustained me with their support and encouragement, and by their example. There are other mentors I’ve met only on the page who’ve sustained me in a more private way. (And I confess, some of them are men.).

November 23, 2014

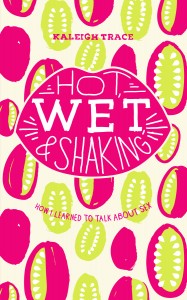

Hot, Wet and Shaking by Kaleigh Trace

The news of three individuals engaging in sexual activity on a streetcar on Thursday night (the King car, even! At rush hour, no less!) resulted in an interesting dinner conversation at our house the other night, leading us to reminisce about the couple who were caught having sex on the Spadina Station subway platform a few years ago (on the north-south line—it’s less busy and the brown circular tiles made for an interesting backdrop in the film of the event, which I watched. So did everyone). We were also wondering how you stage a threesome or any sexual act at all when everyone involved is (presumably) wearing winter coats—Thursday was cold!

The news of three individuals engaging in sexual activity on a streetcar on Thursday night (the King car, even! At rush hour, no less!) resulted in an interesting dinner conversation at our house the other night, leading us to reminisce about the couple who were caught having sex on the Spadina Station subway platform a few years ago (on the north-south line—it’s less busy and the brown circular tiles made for an interesting backdrop in the film of the event, which I watched. So did everyone). We were also wondering how you stage a threesome or any sexual act at all when everyone involved is (presumably) wearing winter coats—Thursday was cold!

“What’s sex?” asked Harriet, who knows where babies come from, but it’s always been a more theoretical concept than something involving actual bodies. And public transit.

It was a moment. Stuart and I looked at each other. I would take this one.

“It’s something that grown-ups do,” I told her. “To make babies, or just for fun. But they should not be doing it on the subway platform. And don’t you forget it.”

Mostly that anecdote is unrelated to Kaleigh Trace’s book, Hot, Wet & Shaking: How I Learned to Talk About Sex, except that I started reading it a few hours after that dinner conversation, and I’m recounting it because it’s a conversation that should go down in history as one of my all-time best parenting successes. I didn’t even miss a beat.

*****

Kaleigh Trace is a sex expert, a person who happens to pull a giant dildo out of her bag in line at the supermarket check-out when she’s fumbling for her wallet. But her book is less a sex guide than a memoir of how she came to be a woman with a dick in her bag, which might have seemed unlikely considering the unsatisfactory nature of her early sexual experiences (which are probably pretty similar to a lot of your early sexual experiences). Her own view of her sexuality is made more complicated by a physical disability resulting from a childhood spinal cord injury—the standard sexual techniques don’t work for her; after years as a patient with whom so much was “wrong”, she has difficulty imagining her body as a vehicle for sexual pleasure.

But the thing about her disability, about “the standard sexual techniques” not working for her is that she’s driven to find the ones that do. To realize that it’s not her body that’s the problem, but instead a rigid view of sexuality defined by lurid billboards and misogyny and internet porn, a view of sexuality that would have us supposing that disabled people (or fat people; or people of colour; or queer people; or old people; or people who aren’t photoshopped) don’t actually exist, or have sex. This is what happens when we don’t talk about sex (on streetcars, or otherwise): other people get to set the terms of sex and sexuality, usually at the expense of one’s own liberty and/or self-esteem.

So Trace’s is a lesson that’s no less valuable to an able-bodied person—that one has to be open to exploring one’s own sexuality on one’s own terms and seeking to discover what works for them, because it turns out that sex isn’t prescribed after all, and everybody/ every body is different. Trace begins to learn this lesson when she finds work at Venus Envy, a Halifax sex shop, a place she is attracted to in the beginning for its wealth of books—new fiction, feminist publications, cultural critiques. Eventually she gets the nerve to venture beyond the book shelves, however, and realizes the world of sexuality is more complicated, messier, and more excellent than she’d ever imagined.

Fitting, for someone with a body, Trace’s identity as a disabled person is connected to her sexuality. She writes of parallel journeys to embrace the queer and disabled labels (the latter which in particular she had spent most of her life pushing up against):

“The labels queer and disabled fit well together and I am honoured to hold them both. They fit together because they both involved resistance. Resistance against those tired ideas of what and how one should be, resistance against presumed and ill-fitting “truths” about the world. In this resistance, both of these words work to create a much-needed space. Space for bodies to be valued in an of themselves space for beauty and love to be redefined.”

There is such generosity to be found in the pages of Hot, Wet and Shaking. Trace’s remarkable and long-sought generosity toward herself, for one thing, which readers should be inspired to embrace in their own experiences. But also generosity too toward her reader, in Trace sharing what she has learned won through her own experiences, her vulnerabilities too, her processes of overcoming (which are, as for all of us, never ending). She’s not just talking about sex, but also talking about language, about being in the world, as a woman, as a person with a disability, a daughter, a girlfriend, a friend. Included in the book also is the story of her abortion, which makes sense because of how abortion is part of so many women’s experiences of sex and being in the world, and the story is important because every time such a story gets told, it becomes clear that abortion isn’t an unspeakable word after all—according to Trace, there are no such things—and that it’s a procedure that happens all the time. As with sex, when we don’t talk about these things, the parameters get set by somebody else and this is dangerous. We all have to have more of a willingness to look life in the eye, and in her candour, her intelligence and sense of justice, Kaleigh Trace is such an inspiration.

Hot, Wet and Shaking is based on Trace’s blog, “The Fucking Facts“, its prose revealing such origins with the very best of what blogs have to offer—the incredible resonance of a single human voice. It’s a funny, fast and absorbing read; powerful, empowering, and so important.

November 20, 2014

I’m Doing It All Wrong

Lately, I can’t shake the feeling that I’m doing it all wrong. I’ve been feeling strange about books, less in love with many I’ve encountered that I’d expected to be (and certainly less than last year when my Top Ten Books of the Year List Had 22 Books In It). We’re coming up to year-end, when we start taking stock, but only a few books are standing out in my mind, and I’m bothered that these weren’t better celebrated by Canadian literary prizes this year. I have also come to the conclusion that there are too many books in my house, which means we should probably call a doctor. Plus I bought 20 new ones last weekend, and I want to read these because perhaps they’ll be the ones I’m waiting for, earning a coveted place on my year-end list.

Lately, I can’t shake the feeling that I’m doing it all wrong. I’ve been feeling strange about books, less in love with many I’ve encountered that I’d expected to be (and certainly less than last year when my Top Ten Books of the Year List Had 22 Books In It). We’re coming up to year-end, when we start taking stock, but only a few books are standing out in my mind, and I’m bothered that these weren’t better celebrated by Canadian literary prizes this year. I have also come to the conclusion that there are too many books in my house, which means we should probably call a doctor. Plus I bought 20 new ones last weekend, and I want to read these because perhaps they’ll be the ones I’m waiting for, earning a coveted place on my year-end list.

But I’m not reading these, instead choosing to read The Stories by Jane Gardam, a doorstopper of a book. It comprises stories from over Gardam’s career, as selected by Gardam herself on the occasion of her shortlisting for the Folio Prize for Last Friends last year (which I loved—I read it in March at Futures Bakery on a rare Saturday morning spent alone). An uneven collection, as reviews have declared, but fascinating in that, and such a joy to escape in.

“Of course, the best antidote to the disappointment of the literary life is to read.” –Caroline Adderson

And so I’m reading, reading, reading, and I don’t even want to talk about what I’m reading. But I do suggest that if you’re a Jane Gardam fan that you should check out this book yourself.

November 19, 2014

Happy to Be Affiliated

We’re getting toward the end of my blogging course, which has been the most wonderful, inspiring experience. I have enjoyed it so much, and look forward to following my students’ blogs as they grow. Though next week is the lesson I know the least about—the business of blogging. Even though my blog is ideal for an affiliation with an online bookseller, but I’ve never done this because I don’t like the predatory practices of the big online booksellers, and don’t want to profit off their gains (which tend to come at a loss for literary culture on the whole).

We’re getting toward the end of my blogging course, which has been the most wonderful, inspiring experience. I have enjoyed it so much, and look forward to following my students’ blogs as they grow. Though next week is the lesson I know the least about—the business of blogging. Even though my blog is ideal for an affiliation with an online bookseller, but I’ve never done this because I don’t like the predatory practices of the big online booksellers, and don’t want to profit off their gains (which tend to come at a loss for literary culture on the whole).

But it recently occurred to me that there was another option. Indeed, Canada’s largest online bookstore, McNally Robinson, does online orders and has an affiliates program, and I’m pleased to announce that Pickle Me This is now a part of it. When you purchase a book by McNally Robinson via a link from Pickle Me This, I will receive a cut of the profits. You can learn more about McNally Robinson’s Affiliate Program here. I will be adding links to my archived book reviews, and links will appear on all posts in the future.

I am pleased to be affiliated with McNally Robinson because I recently used their online ordering system to send a gift to a friend in Vancouver, and was really impressed with their customer service. (The book was not in stock, an actual person emailed to tell me so, and to give me the option of cancelling my order; when the book came in stock a few days later, the person emailed me to let me know.) I will be sending Christmas gifts to my sister’s family in Alberta via McNally Robinson this year for sure now, a nice alternative to Amazon. They don’t have the same discounts, but I’d gladly pay a higher price for the Amazon behemoth not to devour the entire literary world.

And books cost money because books have value anyway.

I am also pleased to be affiliated with McNally Robinson because we had such a good time there last spring when they hosted The M Word. The Winnipeg location is an incredible bookstore, a magical space, and we need more spaces like it in the world. So I’m happy to be directing some business their way, and also pleased to be leveraging this blog as a channel to my becoming a billionaire. When I make my first fortune, I promise to buy you a cup of tea.

Thank you for supporting independent bookstores, and book bloggers too.

November 18, 2014

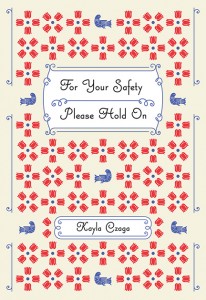

For Your Safety Please Hold On by Kayla Czaga

I’ve written about how I’m learning to be more patient with poetry, but I still relish the experience of a poetry collection I find devourable. Kayla Czaga’s remarkable debut, For Your Safety Please Hold On, begins with “Mother and Father,” a series of poems that journey through a particularly specific set of family albums. Lines like, “My father is more like a poem than most poems/ are. He once tucked a living loon into his coat…” from “Another Poem About My Father.” A narrative arc emerges—the father is an immigrant from Hungary, the mother suffers from serious health problems, and the edges are blurry, but the fine details so clear.

I’ve written about how I’m learning to be more patient with poetry, but I still relish the experience of a poetry collection I find devourable. Kayla Czaga’s remarkable debut, For Your Safety Please Hold On, begins with “Mother and Father,” a series of poems that journey through a particularly specific set of family albums. Lines like, “My father is more like a poem than most poems/ are. He once tucked a living loon into his coat…” from “Another Poem About My Father.” A narrative arc emerges—the father is an immigrant from Hungary, the mother suffers from serious health problems, and the edges are blurry, but the fine details so clear.

In “The Family,” the poet half-steps away from biography to explore family archetypes in the second-person. “Snapdragons, wild garlic, her loose arms/ hugging closed her cardigans, touring/ you around her garden. You visited her/ for two weeks each summer. How strange/ you must’ve seemed, taller every time,/ a girl perhaps she hardly recognized/ except for her daughter’s eyes planted/ into your face…” from “The Grandmother.” Or “The Drunk Uncle”: “wears the same old skill T-shirts for thirty years.”

The collection veers away from narrative in the next section, “For Play,” though we’re still in the same nostalgic terrain (an entire poem inspired by Math Minute assignments!) but the poems are less concrete here, the words the point more than the story they tell. For your safety please hold on, indeed.

And then in “Many Metaphoric Birds,” they take flight, philosophical realms, and I don’t really get it, but that’s okay.

It’s a really wonderful collection.

November 18, 2014

We meet Jon Klassen

Tonight we got to go see Newbery Winner/our hero Jon Klassen at Little Island Comics. He’s on tour promoting his new book with Mac Barnett, Sam and Dave Dig a Hole. He read us I Want My Hat Back and This is Not My Hat, plus my beloved Extra Yarn (and he pointed out that Little Louie was intended to be a baby. Also that Mr. Crabtree was originally naked and hanging out outside the liquor store). He drew a turtle and gave the drawing to Harriet. Then was kind enough to sign our big huge stack of all his books, drawing a picture inside every one, so if we thought these books were priceless before…

Tonight we got to go see Newbery Winner/our hero Jon Klassen at Little Island Comics. He’s on tour promoting his new book with Mac Barnett, Sam and Dave Dig a Hole. He read us I Want My Hat Back and This is Not My Hat, plus my beloved Extra Yarn (and he pointed out that Little Louie was intended to be a baby. Also that Mr. Crabtree was originally naked and hanging out outside the liquor store). He drew a turtle and gave the drawing to Harriet. Then was kind enough to sign our big huge stack of all his books, drawing a picture inside every one, so if we thought these books were priceless before…

November 16, 2014

Inspire

I didn’t know I needed a book fair. Truthfully, my taste for book events are limited because books are my whole life already, and when I go out, it only means less time to read them, and then yesterday I took the escalator up arriving at the Toronto International Book Fair, and I was instantly converted.

It was wonderful.

It was like 49th Shelf, but in real life. Our site, with it’s nearly 80,000 title listings, as I explained to passers-by today as they visited the 49th Shelf booth. These Canadian titles with their beautiful covers, and it’s my job to select which ones to feature on our main page every week, which to include on our lists. So many books, and I know the people who make them, publishers across the country whose good work makes my work so much easier and such a pleasure.

It was like 49th Shelf, but in real life. Our site, with it’s nearly 80,000 title listings, as I explained to passers-by today as they visited the 49th Shelf booth. These Canadian titles with their beautiful covers, and it’s my job to select which ones to feature on our main page every week, which to include on our lists. So many books, and I know the people who make them, publishers across the country whose good work makes my work so much easier and such a pleasure.

And all of a sudden, here the books were, with covers I know so well, but have never touched. My favourite parts of the fair included the Discovery Pavilion, with Ontario Presses like Biblioasis, Coach House, Mansfield Press, Second Story…so many more. Nearby was Breakwater Books, all the way from Newfoundland. And also the booth for All Lit Up, featuring books by independent Canadian publishers. Books by First Nations authors, a display of art by Canadian illustrators, and then I turn a corner and there’s Gordon Korman. Random House and Simon and Schuster had great booths too, and it was so much fun. So many books. I was in book heaven.

I had the most wonderful time yesterday, and left disbelieving that I’d really get to do it all again tomorrow. The fair was oh so good that I brought my kids and family this morning, quite sure that they’d enjoy the kids’ programming in store, and they did, as you can see in this photo of Iris helping out Debbie Ridpath Ohi with her presentation. The fair was well attended but not hugely so, this being the first year, which meant that we could browse without being crowded, and there was room enough for everyone, and room enough even for children to run amuck. It was an excellent atmosphere, and hugely cool presentations—we caught part of Jon Klassen today. I had the pleasure of introducing Catherine Gildiner yesterday, and there were also appearances by Anne Rice and Margaret Atwood, and so so many others. Truly something for everyone.

I had the most wonderful time yesterday, and left disbelieving that I’d really get to do it all again tomorrow. The fair was oh so good that I brought my kids and family this morning, quite sure that they’d enjoy the kids’ programming in store, and they did, as you can see in this photo of Iris helping out Debbie Ridpath Ohi with her presentation. The fair was well attended but not hugely so, this being the first year, which meant that we could browse without being crowded, and there was room enough for everyone, and room enough even for children to run amuck. It was an excellent atmosphere, and hugely cool presentations—we caught part of Jon Klassen today. I had the pleasure of introducing Catherine Gildiner yesterday, and there were also appearances by Anne Rice and Margaret Atwood, and so so many others. Truly something for everyone.

And then there were the books I bought. I couldn’t quit. Believe it or not, I’d intended to buy nothing. Because do I need books? I do not. But then I was there, and it was so good, and such a joy to see so many wonderful publishers being celebrated, to celebrate them myself. By buying their books, of course. The books I know from 49th Shelf, some of which are a little bit mythical, but there they were, and I had to have them. I bought Hot Wet and Shaking: How I Learned to Talk About Sex by Kaleigh Trace, because Harriet picked out the cover (and I have heard many good things about this book). Eating Habits of the Chronically Lonesome by Megan Gail Coles, because I’d featured it on our main page last week and everybody I saw today was walking around with a copy. Diane Schoemperlen‘s because it was reviewed in the newspaper yesterday. Catherine Gildiner’s Coming Ashore, because her presentation was oh so funny. And others still, just because because because. I had to leave finally because my book bag was stuffed and it was getting ridiculous.

And then there were the books I bought. I couldn’t quit. Believe it or not, I’d intended to buy nothing. Because do I need books? I do not. But then I was there, and it was so good, and such a joy to see so many wonderful publishers being celebrated, to celebrate them myself. By buying their books, of course. The books I know from 49th Shelf, some of which are a little bit mythical, but there they were, and I had to have them. I bought Hot Wet and Shaking: How I Learned to Talk About Sex by Kaleigh Trace, because Harriet picked out the cover (and I have heard many good things about this book). Eating Habits of the Chronically Lonesome by Megan Gail Coles, because I’d featured it on our main page last week and everybody I saw today was walking around with a copy. Diane Schoemperlen‘s because it was reviewed in the newspaper yesterday. Catherine Gildiner’s Coming Ashore, because her presentation was oh so funny. And others still, just because because because. I had to leave finally because my book bag was stuffed and it was getting ridiculous.

(“You know, you don’t have to single-handed keep Canadian publishing afloat,” said my husband. Yes, but…)

So what fun, revelling in bookish things, meeting and re-meeting book people—my people. How rare in this day and age to have an event in the publishing industry so big and forward-looking and optimistic. A party instead of a funeral. The world as a bookstore. It was refreshing and so much fun to be celebrating reading, and readers, and writers and books (and booksellers too!). There was nothing tired about it, and being there was such a pleasure.

So what fun, revelling in bookish things, meeting and re-meeting book people—my people. How rare in this day and age to have an event in the publishing industry so big and forward-looking and optimistic. A party instead of a funeral. The world as a bookstore. It was refreshing and so much fun to be celebrating reading, and readers, and writers and books (and booksellers too!). There was nothing tired about it, and being there was such a pleasure.

I’m a bit sorry that we can’t do it all again tomorrow again, but I’m excited to do it again next year.

November 14, 2014

Disposable women, forever and always

We always had true crime books lying around the house when I was little, and since I read everything, these books were no exception, and I do wonder how the 10 year old’s psyche is affected by rigorous rereadings of Blind Faith by Joe McGinniss. I have a better sense of the impact of Wasted: The Preppie Murder by Linda Wolfe, the story of the murder of 18 year old Jennifer Levin in New York City by a man who strangled her in a park and pleaded guilty to manslaughter—the death was a result of “rough sex”, he said. (When police found him the next day, he was covered with scratches. He claimed he’d been attacked by his cat.) Which is that from very early on, I learned that there were some men for whom women were completely disposable, and that our justice system is stacked against victims of sexual violence in a way that is absolutely heinous.

I’ve been thinking about Jennifer Levin’s death since yesterday, when the verdict was delivered in another case involving the death of a teenage girl. We all know her name, but no one is permitted to print it, which means just this: you can indeed be prosecuted for using a rape victim’s name, but you can actually photograph the victim being raped and then share the image on social media—destroying the self-esteem and reputation of a teenage girl, who goes on to commit suicide—and receive a punishment that involves writing a letter of apology and attending a course on sexual harassment. “He must learn how to properly treat females,” is part of the judge’s verdict, as though this is something that must be taught, as though knowing “how to treat females” (who are indeed people) isn’t sort of one of the barest prerequisites for being a human being.

I’ve been thinking about Jennifer Levin’s death since yesterday, when the verdict was delivered in another case involving the death of a teenage girl. We all know her name, but no one is permitted to print it, which means just this: you can indeed be prosecuted for using a rape victim’s name, but you can actually photograph the victim being raped and then share the image on social media—destroying the self-esteem and reputation of a teenage girl, who goes on to commit suicide—and receive a punishment that involves writing a letter of apology and attending a course on sexual harassment. “He must learn how to properly treat females,” is part of the judge’s verdict, as though this is something that must be taught, as though knowing “how to treat females” (who are indeed people) isn’t sort of one of the barest prerequisites for being a human being.

“Why didn’t he help her?” I wonder. The boy with the camera, I mean, or any of his friends, or the police who shrugged when the victim came to them with the actual photo of her rape being committed, and who found no way to prosecute any of the perpetrators (for distributing child pornography—the charge that has a man punished by letter of apology) until after her death by suicide. Why did nobody help?

Let alone, why are there people actually defending the perpetrators? The same kind of people who are bothered by rape charges ruining the lives of nice young men, or promising footballers? What kind of inside out world do we live in? The kind of world in which the parents of a young man who talks about having his colleague raped as a kind of punishment actually speak out in defence of their son? If that were my son, I’d draw the curtains and not go out again for a very long time. Have these people no shame? “We ask you to give him the chance to learn,” the parents say, to which I respond with a vehement, NO. One does not have to learn about how it’s wrong to talk about raping one’s colleagues (or anybody). If you don’t know this already, you never ever will.

When Toronto’s terrible mayor and a godforsaken excuse for a human being was diagnosed with cancer last fall, I fumed as public figures postured about prayers being with him etc. etc. This is another man who has not yet learned that it’s wrong to talk about raping one’s colleagues. It was all I could think of, as his ass fat tumour came down, that a public figure gets to say the things he said (let alone do the things he did) and then get up there with a whole lot of actually honourable citizens and campaign beside them for the job of mayor. “But no!” somebody protests, “do not make disparaging remarks about a man with cancer.” Because we’re willing to draw a line there—we are moral after all—but it’s women who are disposable, women who are nothing more than something for you to stick your dick in, or make jokes about sticking your dick in. A dick receptacle. And if that’s not enough, you can choke them too, “rough sex,” says another public figure, not even sheepishly. And now I’m thinking about Jennifer Levin again, a moment in time, 1980s’s excesses, but it’s forever and always. This is the world in which we live.

You can call it rape culture. You can call it the most horrendous, pervasive male entitlement too. But not all men, another voice pipes up, but oh, there are ever so many. Some of whom are even seemingly feminist allies, examining complicity as they forget about the women whose bodies they themselves have groped, and carrying banners at feminist rallies, even. These men are fathers, husbands, brothers and sons—to frame things in those terms. And I don’t know what to do.

In The New Quarterly 131, Karen Connelly’s essay, “#ItEndsHere,” parallels Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan’s seeming unconcern with the disappearance of 300 school girls with Canada’s own lack of response to the more than a thousand missing and murdered Indigenous girls and women in this country. (The most recent in the news is the young girl in Winnipeg, Rinelle Harper, who was assaulted twice and thrown in the same river where 15 year old Tina Fontaine’s body was discovered months ago. Mercifully, Rinelle Harper survived. She is recovering in hospital.) Connelly reminds us of the rumours surrounding the farm where the remains of so many women were eventually discovered—those rumours would not be investigated for years, during which time so many women died. Disposable women. Ineffectual authorities. There’s a pattern here. It’s like stringing beads.

In The New Quarterly 131, Karen Connelly’s essay, “#ItEndsHere,” parallels Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan’s seeming unconcern with the disappearance of 300 school girls with Canada’s own lack of response to the more than a thousand missing and murdered Indigenous girls and women in this country. (The most recent in the news is the young girl in Winnipeg, Rinelle Harper, who was assaulted twice and thrown in the same river where 15 year old Tina Fontaine’s body was discovered months ago. Mercifully, Rinelle Harper survived. She is recovering in hospital.) Connelly reminds us of the rumours surrounding the farm where the remains of so many women were eventually discovered—those rumours would not be investigated for years, during which time so many women died. Disposable women. Ineffectual authorities. There’s a pattern here. It’s like stringing beads.

Connelly writes, “When there were enough missing women—68 to be exact…—the police finally began to look for them. The investigation into the missing women of the downtown east side began in 1998. [Redacted] continued committing murders until his arrest on February 22, 2002.” And from her poem, “Enough,” from her recent collection, Come Cold River:

Unfold the maps on the table.

Let me show you hell.

As described in The Globe and Mail.

Oddly, it includes English Bay,

blue salt water, sand, crows,

owls in the cedars.

The road out?

Oh, that remains

under construction.