March 31, 2015

The Big Swim by Carrie Saxifrage

Books come from trees, and I’ve got this theory they never entirely shake their wild origins. I think this every time I’m reading outside in the spring and blossoms rain down on my book’s pages, or when a tiny midge appears and sits down at the end of a sentence. The poetry book Decomp by Stephen Collis and Jordan Scott was created from what remained of copies of Origin of Species that had been left in five distinct ecosystems to decay for a year, and I love that idea: of books and reading being so firmly embedded in nature, like they belong there. And in her extraordinary book of essays, The Big Swim, Carrie Saxifrage underlines this point, with references to literary pumpkins (Linus’s, Cinderella’s, and Peter Pumpkin Eater’s wife’s) in her essay on growing a 300 lb. squash; by recounting her grand awakening to the perils of climate change that came with reading—a series of articles by Elizabeth Kolbert; by explaining that she writes about climate change because it’s the one thing that relieves her heartbreak about understanding what we’re doing to our planet; and finally by making the natural world come alive for her reader, capturing the wonderfulness and wondrousness of nature in sparking, evocative prose.

Books come from trees, and I’ve got this theory they never entirely shake their wild origins. I think this every time I’m reading outside in the spring and blossoms rain down on my book’s pages, or when a tiny midge appears and sits down at the end of a sentence. The poetry book Decomp by Stephen Collis and Jordan Scott was created from what remained of copies of Origin of Species that had been left in five distinct ecosystems to decay for a year, and I love that idea: of books and reading being so firmly embedded in nature, like they belong there. And in her extraordinary book of essays, The Big Swim, Carrie Saxifrage underlines this point, with references to literary pumpkins (Linus’s, Cinderella’s, and Peter Pumpkin Eater’s wife’s) in her essay on growing a 300 lb. squash; by recounting her grand awakening to the perils of climate change that came with reading—a series of articles by Elizabeth Kolbert; by explaining that she writes about climate change because it’s the one thing that relieves her heartbreak about understanding what we’re doing to our planet; and finally by making the natural world come alive for her reader, capturing the wonderfulness and wondrousness of nature in sparking, evocative prose.

The next best thing to a tree for a tree to be, I’d say, would be any single page in this extraordinary book.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring meets Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek meets Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love, with a healthy dose of Barbara Kingsolver—perhaps Animal Vegetable Miracle, a book that woke me up to the wonders of eating by the season, local food movements, and that potato have greens—who knew? In 12 absorbing, funny, and thoughtful essays, Carrie Saxifrage connects the personal with the universal and the scientific to the spiritual to celebrate her love for the world and confront her anxiety about its fate.

It’s a perfect book for spring, I think. Partly because bunnies turn up twice. The first time in “Hare,” when Saxifrage writes about tensions between “tree-huggers and rednecks” on her home of Cortes Island, BC. A friend whose family has ties to the local logging industry dares to bridge the gap between the two groups, but it all gets very complicated. (There is a blockade at one point, and Saxifrage offers muffins to everyone on sides, and I do so like that she appreciates the value of the muffin as a political tool.) A long story and good intentions lead to Saxifrage dressing up as “The Easter Hare” (not the bunny, no, this is the pagan symbol for springtime fertility) for the Volunteer Firefighter’s Easter Brunch, but things go wrong as best intentions always do, and our heroine ends up locked in a bathroom with terrifying children threatening to break down the door. In the end, Saxifrage resolves to get on side with her friend’s family by “non-controversial public service” in the future. Hopefully there still can be muffins.

In “Lagomorphic Resonance,” Saxifrage is hiking alone in Washington State, the same places she’d visited years before with a friend who’d later died: “It still felt like some remnant of Paul and me, as we had been, remained in the place itself.” And she’s there to see the pikas, mouselike creatures who are cousins of rabbits and live high up on mountains, who “seem like one of the many improbable details of the world’s enormous diversity.” The essay is partly about rumours of the pika’s endangerment, threats to its habitat by rising temperatures due to climate change, partly about her anxiety as mother of a teenager (and this anxiety hangs over a lot of the text in a really interesting way), about loss and memory, and the tremendous glory of being alone in quiet places.

The essays aren’t so much about what they’re about as they’re about narrative, and so many facts, anecdotes, sidelines adding layers of meaning to the reading experience. In the title essay, Saxifrage swims five miles in the cold ocean between Cortes Island and Quadra Island, capturing the unsexy details of such an endeavour (her entire body covered in lanolin to protect against the cold) and the thrilling ones, about the pleasures of swimming and its movements, of immersion, the challenges of endurance. It’s one of the best bits of swim-lit I’ve ever read: “Romantically speaking, I’m part ocean mammal. I spend time thinking about how real mermaids would actually swim… I’m strongly related to the marine branch of the family tree.” And why does she she partake in the splendid agony of these five mile swims? Because they permit her to “belong…to a vast, cold world where brilliant seaweed banners wave in exultation.”

(So yes, my love of this book also isn’t just because of what the essays are about, but because of how the writing is so incredibly good.)

In “Pumpkin People,” Saxifrage attempts to make her way into the community on Cortes Island where she has arrived as a homesteader (and one who was previously an American lawyer, no less…) by participating in the annual ritual of growing outsized gourds; in “Hail Mary, Shining Sea” she is awakened to the reality of climate change and its threats to the planet, this idea mingling with notions of “goodness”; pursuing a low-carbon lifestyle, she and her husband eventually stop flying, and so it’s by Greyhound bus that she makes her way to Mexico for adventure and Spanish lessons and to be part of a shining sea in a metaphoric way. “Deep Blueberry Gestalt” is Saxifrage hiking through Vancouver’s Strathcona Park alone while reading Arne Naess’s ideas about “possibilism”: “that we must decisively come up with our view of life and find meaning in it, yet remember that more things are possible than we can imagine.”

In “The Oolichan and the Snake,” she attempts to understand First Nations opposition to the proposed Northern Gateway Pipeline by taking the Greyhound for 20 hours to Kitimat in Northern BC to listen to First Nation testimony. “A lot of people don’t understand how industrious our people really were,” explains Gerald Amos, an elder of the Haisla Nation. “On this river alone, we estimate that our people harvested 600 tonnes of oolichan in the springtime. This went on for untold generations. We’ve made our living here for thousands and thousands of years without destroying it.”

“Nectar” is a beautiful story of Saxifrage’s mother’s final days, and contains one of the loveliest lines I’ve ever read: “Maybe when you love someone…you are preparing for a moment you don’t even realize will come.” “Falling into Place” is about a confluence of her mother’s death with the discovery of an ancient human jawbone on their property. “Journey to Numen Land” I loved because Saxifrage decides that sleeping a lot is radical, and she attempts to draw connections between her sleeping and waking life to fascinating ends. She returns to the water in “River Creatures,” rafting through the Grand Canyon and swimming (of course!) part way, making connections between her mother, the fossilized creatures in the canyon walls and river guides who’d gone before her: “None of them got to preserve for all time what they loved, or even completely determine their own course. Like me, they had the opportunity to study the rapids, choose their path, and find joy in the river’s firm embrace.”

March 29, 2015

Preparations for Travel

The first step in getting ready for our trip to the UK next month is revisiting these bookish volumes which will no doubt inform many of our adventures!

March 29, 2015

Easy, healthy, delicious wholewheat banana pancakes

On the occasion of it being Sunday, I wanted to share with you my recipe for the easy, healthy, delicious wholewheat banana pancakes I make for my family every Sunday morning (while reading the paper, of course), once I finally manage to get out of bed. This recipe has so thoroughly been adapted that it’s totally mine. And now it also can be yours!

On the occasion of it being Sunday, I wanted to share with you my recipe for the easy, healthy, delicious wholewheat banana pancakes I make for my family every Sunday morning (while reading the paper, of course), once I finally manage to get out of bed. This recipe has so thoroughly been adapted that it’s totally mine. And now it also can be yours!

It’s a very forgiving recipe with measurements so exactness is not required (and banana size may vary, so that’s a good thing). Basically, if the batter is too gloopy, add more flour, and if it’s too thick, add more milk until you reach your desired consistency.

Serves 2 adults and 2 children, with a couple of pancakes left over. The children will have eaten the leftover pancakes by lunchtime if you leave them out on the counter on a plate.

Ingredients:

1 cup of buttermilk (a tablespoon of lemon juice turns milk into buttermilk)

2 eggs

2 or 3 ripe bananas, mashed

1 cup of wholewheat flour

2 teaspoons of baking powder

1/4 teaspoon of salt

Coconut oil (which we only use because it’s trendy, but vegetable oil will suffice)

Directions:

1) Whisk buttermilk, eggs and mashed bananas together in a medium-sized bowl.

2) Add the dry ingredients and whisk until the batter is smooth.

3) Melt 1 tablespoon of coconut oil in whatever pan you happen to have.

4) Add 1/4 of a cup of batter to the pan once the oil is hot (i.e. sizzles when you flick some water at it). Add a few other 1/4 cups, leaving room between pancakes. Pick up the newspaper and read an article or two.

5) Flip the pancakes when bubbles have appeared on the top and/or edges are browned and/or when pancakes are formed enough for easy flipping.

6) Don’t worry if they’re a little overcooked—the maple syrup will eliminate any problems with that. Read more of the paper while cooking for 2 or 3 minutes until the bottom side is browned, and then remove from the pan.

7) Repeat with the rest of the batter.

8) If you finish reading the paper, enjoy in the company of a good book. Serve with maple syrup and fresh fruit. And tea. Always tea. (Below is a photo of my last Sunday. It was a good one.)

March 26, 2015

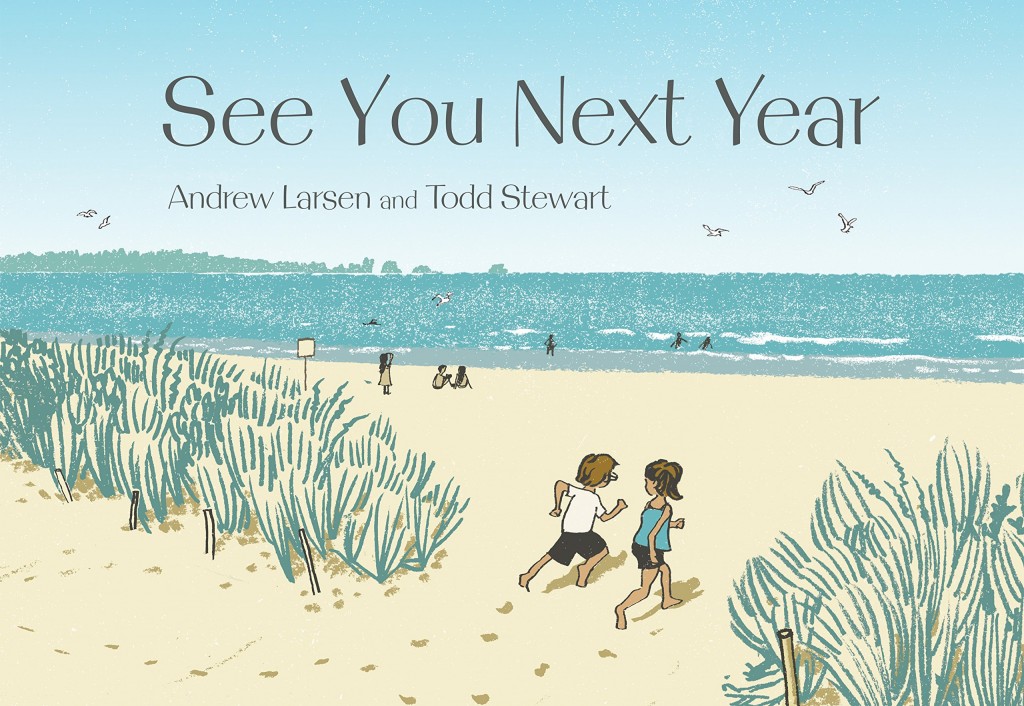

See You Next Year by Andrew Larsen and Todd Stewart

Our first Andrew Larsen book was The Imaginary Garden, which was a Best Book of the Library Haul almost 4 years ago. Since then I’ve raved about his other books, including In the Tree House and Bye Bye Butterflies, and even more important (though not more important than that he was a finalist for the TD Children’s Literature Award in November), Andrew has become my friend. We met first at the library, obviously, and because we live in the same neighbourhood, we get to walk together to school pick-up when circumstances are fortuitous. I enjoy his company immensely, and have been oh so looking forward to his new book, See You Next Summer, illustrated by Todd Stewart. And happily, it’s everything I was hoping it would be.

It’s a simple story celebrating ordinary wonders, the things we can count on, articulated in the perfect, slight-wistful child’s eye view that Larsen is becoming known for. And it’s a summer book, about a girl whose family returns to the same beachside motel for their vacations every year (“I call it our cottage. But it’s not really a cottage.”—and I appreciate that Larsen’s stories often reflect more modest economic realties, the kind we’re more familiar with in our family). It’s a place where nothing ever changes. On Sunday morning, the girl watches the tractor rake the beach, on Monday nights they go into town to the bandstand where a band plays, and on Tuesday it’s foggy, and so on. Though one thing is different this year—she’s made a new friend. They write postcards together, play in the waves, dig in the sand and roast marshmallows in a bonfire on the beach. And that’s it really. There is a twist at the end that’s really lovely, but it does nothing to counter the constancy of the narrative, to undermine the girl’s faith in sure things. Which I love—this simple celebration of rituals we build our lives around, an articulation of faith a bit less cloying than, say, The Carrot Seed. A affirmation that there are good things in the world, things to count on. Sure, the real world is going to come along and challenge the girl’s faith at some point, because that’s what growing up is, but not everything will get broken. Moreover, in this ever changing world in which we live in (to quote a Beatle), it really is the present moment that matters, and Larsen captures it splendidly—the confidence of the child who knows what she knows, whose confidence of her place in the universe is unquestioned, unshaken. It’s the sort of security that every child deserves to grow up amidst.

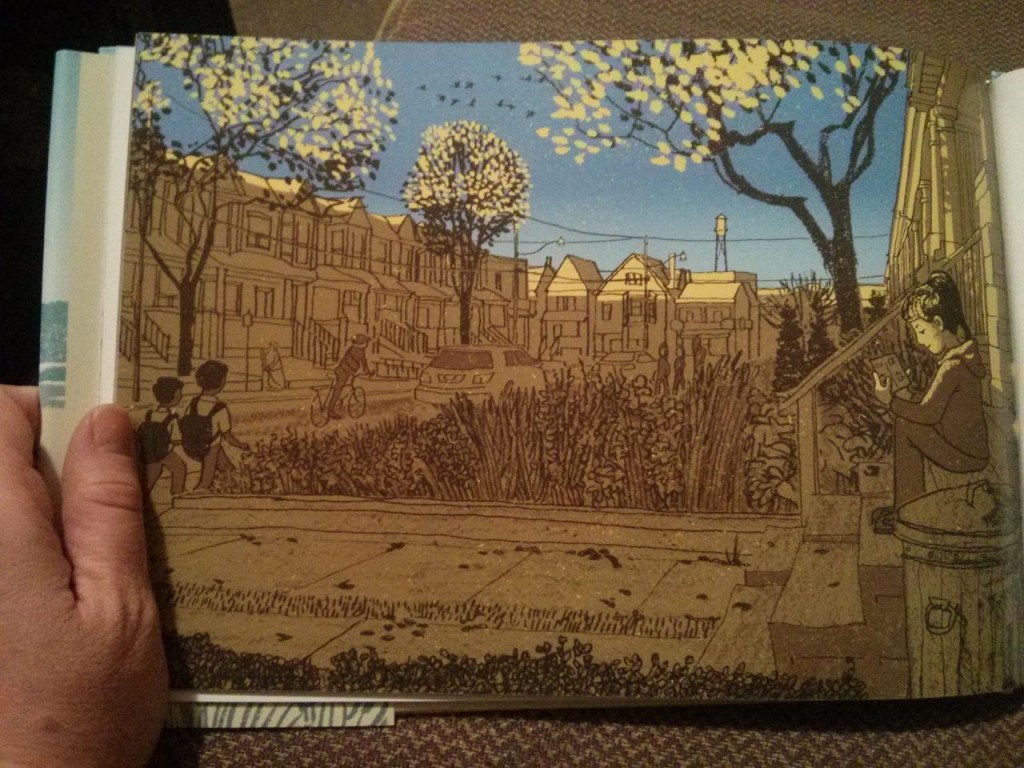

Todd Stevens’ illustrations are completely enthralling due his fascinating use of light. See the porch light above (with the red sunset just on the horizon), and the sunrise over the city with half the street still in shade, and elsewhere in the book, the shadow from beach umbrellas, the shadow of evening in later afternoon, how a streetlight shines through fog, the lights of the campfire, from shooting stars, the silhouette of the friend waving against the sun as the girl watches him through the back window of the car as her family begins their journey home. (On the very last page of the book, there is a light switch. I find this most significant, of course). And it occurs to me that his use of light is perfect to show the passage of time during a period in which nothing changes—Virginia Lee Burton pulled off a similar trick with The Little House. Suggesting that things are actually changing all the time, the world around us ever in flux, but that all change is part of a cycle. The images adding an additional layer of depth and poignancy to Larsen’s tale.

March 25, 2015

A Year of Days by Myrl Coulter

The title and premise of Myrl Coulter’s essay collection, A Year of Days, bring to mind the quote by Annie Dillard: “How we spend our days is how we spend our lives.” But considering its inverse, Coulter’s essays examining the shapes of our lives by the days a life comprises, the singular days upon which time hangs its hat, and that become our markers from year to year to year. February, birthdays, the August long weekend, Thanksgiving, Halloween. In a life forever changing, it’s these days that are ever constant, to be counted on, and the seasons too, cycles returning every year, and it’s only you who has become so different. Our connections to these days are visceral—sometimes in anticipation, or anxiety, or happiness, or grief. And it’s this viscerality (a word she coins) as well as the days themselves that are points of departure for the essays in this book. New Years Day, for the first essay, a calm day, the chance to start again. All the while she’s mourning the death of her mother, irrevocably lost.

The title and premise of Myrl Coulter’s essay collection, A Year of Days, bring to mind the quote by Annie Dillard: “How we spend our days is how we spend our lives.” But considering its inverse, Coulter’s essays examining the shapes of our lives by the days a life comprises, the singular days upon which time hangs its hat, and that become our markers from year to year to year. February, birthdays, the August long weekend, Thanksgiving, Halloween. In a life forever changing, it’s these days that are ever constant, to be counted on, and the seasons too, cycles returning every year, and it’s only you who has become so different. Our connections to these days are visceral—sometimes in anticipation, or anxiety, or happiness, or grief. And it’s this viscerality (a word she coins) as well as the days themselves that are points of departure for the essays in this book. New Years Day, for the first essay, a calm day, the chance to start again. All the while she’s mourning the death of her mother, irrevocably lost.

“As soon as she was gone from this earth, I felt an overwhelming need for more of her. I had to find her again. But how do you find someone after they’re gone for good? That’s where viscerality comes in handy. My viscerality took me on a trek into the years my mother and I had spent on the planet, both together and apart.”

Like many of my favourite essay collections though, the thematic here link is tangential. Even the essays themselves embark upon wild twists and diversions. Coulter’s essays fit Susan Olding’s definition of the genre, in which she writes, “Partaking of the story, the poem, and the philosophical investigation in equal measure, the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go… We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave.” And with the book as a whole, you start out expecting a book that’s a kind of calendar, only to find that Myrl Coulter has cast her net so very wide.

And what has she captured? The magnificent frigate bird swooping over the sea, seen from the hotel where Coulter partakes in a Mexican sojourn. How does one capture a sunset? Winter as an analogy for her mother’s dementia, casting their family into a season of darkness. An essay on Valentines, and hearts real and metaphoric, and perforated hearts, and the difficulty of cutting while left-handed with right-handed scissors. On Easter, and Easter Island, and Easter Bunnies, and the lies we tell our children for the sake of magic. I love this essay’s ending: “Nostalgia lives in the impossible notion that we can start again… I suppose that makes nostalgia a little like repentance.”

I loved the essay, “Gym Interrupted, Again,” in which Coulter contemplates the work-out clothing she’s acquired over decades, considering her high school PE uniforms, ’80s aerobic sweatbands, expensive running shoes, bagging jogging pants, running tights, and all the changing fashions of fitness and its attire, and the body, the one constant (though in itself, ever changing). “But one relationship we have that isn’t interrupted, at least until the day it ends forever, is the one we have with our bodies. They are the houses we live in.”

She writes about her discomfort with Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, built on idealized notions that often please no one. About the May long weekend, and her surprise that golfing has become part of her life, articulating what she loves about the sport in a way I found fascinating. “Lakes I Have Known” is summer and swimming and floating free. “Cornocopia Soup,” sort of about Thanksgiving, but essentially a recipe for making Chicken Soup over two days, about loneliness and soup-making as therapy, and it made me so hungry. “Survival Gear,” which riffs on Halloween and costumes, and our selves as costumed beings, and ends with, “Words and pictures—survival gear for our stories.”

“Wearing Black” on funerals and mourning, and the surprising “Music on the Hill” about the ins-and-outs of the Edmonton Folk Music Festival, and its peculiar and particular rituals recurring year after year, and she writes about these experiences while numbed by grief, after her mother’s death, of “my distraction year” when “my inner music stopped.” The collection ends with the weird and wonderful “Current Crossings” about Edmonton’s High Level Bridge and its various modes of crossing. Back and forth, back and forth, the traffic flowing like time is, and bridges are metaphors for so many things—for the possibility of connection, for how here we are between one thing and another, or the bridge itself as a year and every journey across it is so very different.

If Myrl Coulter’s name sounds familiar, it may be because she was a contributor to The M Word, her essay actually an excerpt from her phenomenal book, The House With the Broken Two. While Coulter’s complex relationship with her mother is an important aspect of her memoir, it’s considered more obliquely here. A Year of Days is not so much a book about grief as a book that’s haunted by Coulter’s mother’s spirit. As the whole world might seem to be after a loss, I’d suppose, the collection creating some order from the pieces that are left.

March 25, 2015

Pickle Me This: The Digest

You’ll see up in the top of the right-hand column that I’ve started a Pickle Me This newsletter, which will be referred to with the far more literary title of “Digest.” The Pickle Me This Digest will be the best of the blog delivered each month to your inbox with a smattering of book reviews, picture book reviews, and other features. I know that fewer people are visiting blogs on a regular basis these days, and instead come to specific posts via social media links, which is all fine and well, but I thought the Digest might be a great resource for anyone who’d like to stay better in touch on a regular basis.

You’ll see up in the top of the right-hand column that I’ve started a Pickle Me This newsletter, which will be referred to with the far more literary title of “Digest.” The Pickle Me This Digest will be the best of the blog delivered each month to your inbox with a smattering of book reviews, picture book reviews, and other features. I know that fewer people are visiting blogs on a regular basis these days, and instead come to specific posts via social media links, which is all fine and well, but I thought the Digest might be a great resource for anyone who’d like to stay better in touch on a regular basis.

Even better? Anyone who signs up for The Pickle Me This Digest in the next month will have their name entered in a draw to win a copy of the essay anthology I edited, The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, which was published last year by Goose Lane Editions. Mother’s Day is coming up soon, so the book is timely. And if you have a copy already? Well, why not pass your extra copy along to a friend? As Deborah Ostrovsky wrote in the Fall 2014 issue of Herizons magazine, “… You won’t keep this book; you’ll pass it on to friends whose current vocation is changing diapers, or to friends who want a child, and those who don’t.”

Even better? Anyone who signs up for The Pickle Me This Digest in the next month will have their name entered in a draw to win a copy of the essay anthology I edited, The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, which was published last year by Goose Lane Editions. Mother’s Day is coming up soon, so the book is timely. And if you have a copy already? Well, why not pass your extra copy along to a friend? As Deborah Ostrovsky wrote in the Fall 2014 issue of Herizons magazine, “… You won’t keep this book; you’ll pass it on to friends whose current vocation is changing diapers, or to friends who want a child, and those who don’t.”

If you’ve already signed up for the newsletter, I’ll add your name to the draw. And as ever, thank you for your support of Pickle Me This!

March 25, 2015

After Birth: Redux

Redux is the wrong word. I haven’t stopped thinking about After Birth since I finished reading it last week. This morning I had the most interesting conversations with a woman who is a newish friend of mine (and don’t you find that new friends become more and more precious as one gets older?) with whom I’ve had the pleasure of so much company over the past few months while she’s been on maternity leave with her third child. Fortuitously, her house is a stone’s throw from mine, her son and Harriet are passionate friends, she’s so ridiculously smart and funny, and she just read After Birth. (I wish every woman a friend with whom to discuss After Birth.) So this morning we sat around my living room while my baby mauled her baby, and we talked about the book, how it made us both uncomfortable. Because, I think, I said, trying to put my finger on it, it doesn’t tidy up. Nothing is resolved, it moves is a circle. It is an unsatisfying book, which I mean as the highest literary praise. Like another fine book, Harriet the Spy, After Birth is about a female person who doesn’t change, who doesn’t stop ranting, who doesn’t stymy her anger. And we need this anger, I think—to seize on its power—, and we need this insistence on circuity, as opposed to the narratives we’re being sold most of the time about how we should tuck our anger and our lives, our selves, inside tiny tidy boxes. We’re being sold narratives of binary—breast and bottle, wohms and sahms. Just today, there is an online fracas because someone wrote an inane justification for stay-at-home-momming (don’t seek it out or read it. Nothing new under the sun. Argument is best articulated and refuted here). The writer articulating her lifestyle in opposition to somebody else’s, and I just though, how boring. I thought about the writer’s argument in contrast with the vibrant thinking I was a part of this morning, and all I could think of to say to her is, I wish for you the freedom to live your life on your own terms. Not to care anymore. Not to have to purport to have all the answers, or believe there even needs to be an answer. We’re all cobbling together our pieces, and the patterns don’t have to be the same. And yes, I wish for the public conversations about motherhood to be like the ones we’re having in private: the passionate, expansive ones that are challenging, rich and about the whole wide world.

Redux is the wrong word. I haven’t stopped thinking about After Birth since I finished reading it last week. This morning I had the most interesting conversations with a woman who is a newish friend of mine (and don’t you find that new friends become more and more precious as one gets older?) with whom I’ve had the pleasure of so much company over the past few months while she’s been on maternity leave with her third child. Fortuitously, her house is a stone’s throw from mine, her son and Harriet are passionate friends, she’s so ridiculously smart and funny, and she just read After Birth. (I wish every woman a friend with whom to discuss After Birth.) So this morning we sat around my living room while my baby mauled her baby, and we talked about the book, how it made us both uncomfortable. Because, I think, I said, trying to put my finger on it, it doesn’t tidy up. Nothing is resolved, it moves is a circle. It is an unsatisfying book, which I mean as the highest literary praise. Like another fine book, Harriet the Spy, After Birth is about a female person who doesn’t change, who doesn’t stop ranting, who doesn’t stymy her anger. And we need this anger, I think—to seize on its power—, and we need this insistence on circuity, as opposed to the narratives we’re being sold most of the time about how we should tuck our anger and our lives, our selves, inside tiny tidy boxes. We’re being sold narratives of binary—breast and bottle, wohms and sahms. Just today, there is an online fracas because someone wrote an inane justification for stay-at-home-momming (don’t seek it out or read it. Nothing new under the sun. Argument is best articulated and refuted here). The writer articulating her lifestyle in opposition to somebody else’s, and I just though, how boring. I thought about the writer’s argument in contrast with the vibrant thinking I was a part of this morning, and all I could think of to say to her is, I wish for you the freedom to live your life on your own terms. Not to care anymore. Not to have to purport to have all the answers, or believe there even needs to be an answer. We’re all cobbling together our pieces, and the patterns don’t have to be the same. And yes, I wish for the public conversations about motherhood to be like the ones we’re having in private: the passionate, expansive ones that are challenging, rich and about the whole wide world.

March 23, 2015

Where I Find the Time to Read

I read a lot. I read for a living, and I read to save my life, and, “Where do you find the time to read?” is a question that continues to baffle me. It’s like being asked where I find the air to breathe. The time, like the air, is out there in abundance, and having children hasn’t changed that. It just means I have to be creative in finding a way to make that time my own.

I read a lot. I read for a living, and I read to save my life, and, “Where do you find the time to read?” is a question that continues to baffle me. It’s like being asked where I find the air to breathe. The time, like the air, is out there in abundance, and having children hasn’t changed that. It just means I have to be creative in finding a way to make that time my own.

The following is a list of ordinary occurrences disguising excellent opportunities to steal a moment with a book.

- Extended Breastfeeding: Of the many benefits of breastfeeding, the time to read in is paramount. Once you’ve mastered holding a book open with one hand, it’s effortless, and oh so efficient—nourish a baby and your mind in a single shot. When my first daughter finally weaned at age 2 ½, I so mourned the loss of reading time that I had to have another baby.

Before Bed: Every night, there is a window of sometimes up to ten minutes between the moment my head hits the pillow and when the baby awakes, and so I read then. And when the baby does awake, I breastfeed her. (See previous point.)

Before Bed: Every night, there is a window of sometimes up to ten minutes between the moment my head hits the pillow and when the baby awakes, and so I read then. And when the baby does awake, I breastfeed her. (See previous point.)

- Weekend lie-ins: Obviously, I don’t get out of bed in the mornings. Would you? On Saturday and Sunday mornings, there is always time to get a chapter in before I return to the vertical life, and if I stay in bed long enough, somebody probably will bring me a cup of tea. And then I don’t have to get up until I’ve drunk it.

Walking: Walking while reading is walking the one risky behaviour I indulge in on a regular basis. Doing it while pushing a stroller is even more reckless, I realize, but sometimes one has to live on the edge. Also, I could make it to kindergarten and back with my eyes shut, so there’s no harm in doing with text in front of my face.

Walking: Walking while reading is walking the one risky behaviour I indulge in on a regular basis. Doing it while pushing a stroller is even more reckless, I realize, but sometimes one has to live on the edge. Also, I could make it to kindergarten and back with my eyes shut, so there’s no harm in doing with text in front of my face.

- At the playground: I will argue that reading at the playground is not entirely the opposite of being present for my children, mostly because there are only so many mud-pies I can pretend to gleefully devour. Also, every time they look up at the bench and see me reading there, I’m increasing their own chances of being readers by setting a good example. Everybody wins.

During interruptions: Basically, I find the time to read by always having a book in my bag. Sometimes two. And this means that when my husband takes the kids to the bathroom after a restaurant meal, I can finish a chapter along with the dregs of my tea.

During interruptions: Basically, I find the time to read by always having a book in my bag. Sometimes two. And this means that when my husband takes the kids to the bathroom after a restaurant meal, I can finish a chapter along with the dregs of my tea.

- Sitting alone in restaurants by myself: And other times, I forfeit the husband and kids altogether, and take myself out for a chai latte and oversized cookie, or even an entire lunch, and read the entire time. Cultivate your own company, is what I mean, and you will get so much reading done.

- In waiting rooms: As a parent with a book in her bag, there is nothing more luxurious than having to wait for appointments while the children are asleep in their strollers or in the care of somebody else. I’ve spent some of the best afternoons of my life in recent years reading for solid blocks of time at the passport office, my doctor’s, or the dentist.

- While flossing: Regarding the dentist, I have never before been so attentive to dental hygiene. I’ve become a vigilant flosser since I learned to floss and read, which is a skill involving holding open a book with my feet. I do this daily. For ten to twenty minutes at a time.

- In the bathroom: Also, for ten to twenty minutes at a time. My digestive system is getting a bad reputation. But there is a door that locks and a stack of books nearby—why would I ever leave?

Pancakes: I don’t spend all my time avoiding my family, however. Every Sunday, I make whole-wheat banana pancakes from scratch, which sounds selfless and well-meaning until I explain that once the batter is mixed, I pull out what’s left of the Saturday paper, flipping the pancakes between articles. (“Go away. Mommy is cooking.”)

Pancakes: I don’t spend all my time avoiding my family, however. Every Sunday, I make whole-wheat banana pancakes from scratch, which sounds selfless and well-meaning until I explain that once the batter is mixed, I pull out what’s left of the Saturday paper, flipping the pancakes between articles. (“Go away. Mommy is cooking.”)

- But not at the table. Unless it’s breakfast or lunch…We don’t permit reading at the table at our house, because meals are a time for togetherness. We bend the rules for breakfast and lunch though, because bendy rules are useful for teaching flexibility. And because tables are so useful for having the Saturday paper spread across.

March 19, 2015

The Bus Ride by Marianne Dubuc

We’re becoming big fans of Marianne Dubuc’s books at our house, having enjoyed In Front of My House and Animal Masquerade. You will recall that picking up the latter title resulted in our entire family eventually assembling on the couch, gathering together captured by the book’s magic, and laughing hysterically at the surprises and absurdity. Dubuc’s latest book, The Bus Ride, similarly engages and surprises, and while it’s is very loosely based on the Little Red Riding Hood narrative, a more fitting descriptive for the story would be “curiouser and curiouser.”

We’re becoming big fans of Marianne Dubuc’s books at our house, having enjoyed In Front of My House and Animal Masquerade. You will recall that picking up the latter title resulted in our entire family eventually assembling on the couch, gathering together captured by the book’s magic, and laughing hysterically at the surprises and absurdity. Dubuc’s latest book, The Bus Ride, similarly engages and surprises, and while it’s is very loosely based on the Little Red Riding Hood narrative, a more fitting descriptive for the story would be “curiouser and curiouser.”

The Bus Ride is the story of a little girl’s first ride along on a city bus to visit her grandmother’s house. Her mother sees her off at the bus stop, ensuring she’s got a snack and a sweater in case she gets cold. And from there the rest of the story is of the bus ride, the bus’s interior each two-page spread. Passengers embark at the front doors and alight through the back. The little girl narrates what she sees in a sentence or two, although the real story is happening in Dubuc’s illustrations. A cat is knitting a scarf that grows ever-longer, a mouse is reading a tiny book, a family of rambunctious moles (I think?) climbs on board and end up swinging from the overhead bars (and one chews on a piece of gum he finds on the floor). A family of wolves boards the bus and the little girl makes friends with the wolf-boy who’s about her age—they share her cookies. A sleepy sloth snoozes the ride away. Someone’s hiding behind a newspaper whose headlines are ever-changing and reference what’s going on the pictures. I admired in the stolid bear in his big blue boats.

They pass through the forest, through a tunnel. Children run amuck. The fox keeps sleeping. The owl woman in the hat seems quite uncomfortable, and characters keep turning up in different places. The turtle gets nervous and hides in his shell. A wannabe pickpocket—a fox, of course—boards the bus, and and the little girl helps to divert a crime. And what is the beaver carrying inside his really big box?

They pass through the forest, through a tunnel. Children run amuck. The fox keeps sleeping. The owl woman in the hat seems quite uncomfortable, and characters keep turning up in different places. The turtle gets nervous and hides in his shell. A wannabe pickpocket—a fox, of course—boards the bus, and and the little girl helps to divert a crime. And what is the beaver carrying inside his really big box?

While The Bus Ride is first a story of one girl’s first independent journey into the world, it’s fundamentally a story of how interesting the world is and how fascinating it is to be in the midst of it all. At the end of the bus ride, the little girl reflects on all the stories she has to tell her grandmother now. Hers is an apprenticeship in narrative, but it is for the reader as well, who assembles her own story based on the curious scenes depicted in Dubuc’s illustrations, which are detailed and accessible, appealingly rendered in pencil crayon. And like all the very best picture books, it’s completely different with every encounter.

March 19, 2015

A sign of spring

I love the springs that arrive like this, like an unexpected gift instead of something long overdue. Spring is not quite here yet, but it’s making itself known, the way the green of a crocus appears like a dot in the dirt (and the way a tooth first appears, a dot of white on a baby’s gum—this is my metaphor lately). There are no leaves on the trees and the air still has a chill, but look how the sky is blue, the snow is gone, and our household’s sheets are drying on the line.

I love the springs that arrive like this, like an unexpected gift instead of something long overdue. Spring is not quite here yet, but it’s making itself known, the way the green of a crocus appears like a dot in the dirt (and the way a tooth first appears, a dot of white on a baby’s gum—this is my metaphor lately). There are no leaves on the trees and the air still has a chill, but look how the sky is blue, the snow is gone, and our household’s sheets are drying on the line.

Though the surest sign that it isn’t spring (yet) is how cold were my hands after hanging out the sheets. Soon though…

I was inspired to hang out the sheets from Sarah’s blog post about hanging out her washing (and her comments on the magical high-up washing lines with pulleys that need to be hauled in and out—I dream of these, though they terrify me also. What if something comes loose and my pillowcase falls down six stories, lost forever). It strikes me what a literary thing is clothes on the line—indeed, as I was hanging the sheets this morning, the “Grandma hanging washing on the clotheslines to be dried” line kept bouncing through my head from Peepo.

I was inspired to hang out the sheets from Sarah’s blog post about hanging out her washing (and her comments on the magical high-up washing lines with pulleys that need to be hauled in and out—I dream of these, though they terrify me also. What if something comes loose and my pillowcase falls down six stories, lost forever). It strikes me what a literary thing is clothes on the line—indeed, as I was hanging the sheets this morning, the “Grandma hanging washing on the clotheslines to be dried” line kept bouncing through my head from Peepo.

For more on literary washing, do read Anita Lahey’s blog post, “Oh, let there be nothing on earth but laundry.” (Lahey had a poem included in the anthology, Washing Lines, a collection of poetry of laundry and washing.) And see also Matilda Magtree (Carin Makuz) with “Pinning, Pining and Penning,” about repairing clothespins and other essential acts.