May 21, 2015

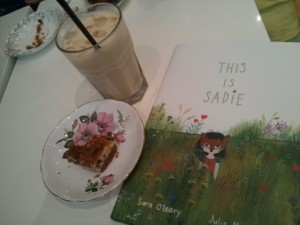

This is Sadie by Sara O’Leary and Julie Morstad

I have a special affinity for This is Sadie, the gorgeous new collaboration by Sara O’Leary and Julie Morstad (whose When You Were Small and other books in the Henry series I have loved since before I had my own small people to love them with). I like to imagine it was written just for me.

It’s got bunting, and swimming, and tea parties, and paper dolls, and even squids, and a spirited girl who gets lost in a whole wide world of books.

It’s got everything that made Morstad’s award-winning How To so wonderful—the mermaid girl, a pair of legs revealing someone hiding in a tree. Plus, O’Leary provides the mischief of Judith Viorst’s and Hilary Knight’s Sunday Morning, the bookish inspiration of Charlie Cook’s Favourite Book by Julia Donaldson, and allusions to Alice in Wonderland, The Jungle Book, Little Red Riding Hood, and Rapunzel. It’s a book about passing time. reading books, and how Sadie likes to make “boats of boxes/ and castles out of cushions./ But more than anything she likes stories,/ because you can make them from nothing at all.” We see Sadie in bed reading a book called The Story of a Snail, then by the next page, her boat box has been transformed into a snail shell.

Morstad’s illustrations are full of jokes and details, things to discover—an apple with a bite out of it, Sadie’s abandoned shoes, a toadstool bedside lamp, a mysterious family of tiny foxes. The book reminds me of Carson Ellis’s Home in how things from around Sadie’s room and in her books recur as images in her imaginings—just as Ellis’s own artist uses the things around her as inspiration for the illustrations in her book. Both This is Sadie and Home make connections between the world around us and where we go in our dreams.

And what anyone needs for dreaming is room to explore. “In This is Sadie, it is pretty easy to draw a direct line between boredom and creativity,” writes O’Leary on her blog, underlining the importance of giving kids the opportunity to make their own play, to dream their way into all kinds of stories—the mermaid, the boy raised by wolves, and “the hero in the world of fairy tales.”

“The days are never long enough for Sadie. So many things to make and do and be.”

May 21, 2015

You can win a copy of Mad Miss Mimic!

On Tuesday night, I had the pleasure of attending the launch for Sarah Henstra’s novel, Mad Miss Mimic. It was even more fantastic than the book, if you can believe it, with strings and strings of bunting. teacups, tiered plates with squares and sandwiches, fancy hats, and an entire choir performing. You can check out a couple of photos here, one with me beaming. It was that kind of night.

On Tuesday night, I had the pleasure of attending the launch for Sarah Henstra’s novel, Mad Miss Mimic. It was even more fantastic than the book, if you can believe it, with strings and strings of bunting. teacups, tiered plates with squares and sandwiches, fancy hats, and an entire choir performing. You can check out a couple of photos here, one with me beaming. It was that kind of night.

And naturally, I bought the book. But I already had a copy, which means there is one going spare now, and I’m going to give it away to someone signed up for the Pickle Me This Digest, as determined for a random draw. Sign up by June 15 for a chance to win. And those of you already on the list are automatically entered in the draw.

- Read my review of Mad Miss Mimic.

May 20, 2015

Survival Gear for Our Stories

A lot went wrong when my first child was born, most of it involving the loss of my mind, but there was also the fact of the loss of my hard drive when the baby was four weeks old. I lost everything on my computer, which was actually kind of liberating—this all happened on the day I turned 30, and I was intrigued by the idea of a fresh start, a clean slate as I embarked upon a brand new decade. The only thing we lost that I truly regretted were photos, unflattering ones taken soon after the birth, photos of us in the recovery room as we were learning to breastfeed for the very first time. These were the kind of photos one wouldn’t post on Facebook, all bare boobs and double-chins, and besides, I was still then the kind of person who didn’t want to put too many pictures of my child on Facebook. I didn’t want to be one of those people.

A lot went wrong when my first child was born, most of it involving the loss of my mind, but there was also the fact of the loss of my hard drive when the baby was four weeks old. I lost everything on my computer, which was actually kind of liberating—this all happened on the day I turned 30, and I was intrigued by the idea of a fresh start, a clean slate as I embarked upon a brand new decade. The only thing we lost that I truly regretted were photos, unflattering ones taken soon after the birth, photos of us in the recovery room as we were learning to breastfeed for the very first time. These were the kind of photos one wouldn’t post on Facebook, all bare boobs and double-chins, and besides, I was still then the kind of person who didn’t want to put too many pictures of my child on Facebook. I didn’t want to be one of those people.

The baby had only been around for four weeks, but those early weeks are such times of enormous change. At four weeks, she’d already amassed multitudinous selves, passed through several incarnations, and it was impossible to keep track of all them. And most of that was irrevocably lost when my hard drive went kaput, taking all my photos with it. Except, ironically, for the few photos I had posted on Facebook—an exercise I’d undertaken with remarkable restraint. And suddenly, those few photos were the only ones I had. Facebook was my saviour—who’d ever have imagined?

So I was converted by the time my second daughter was born four years later. There were going to be so so many pictures. We were also going to have her photographed immediately after her birth by ceasarean, all purple and gloopy and as foetal as she’d ever be again. I wanted to see it. I’d missed it before, when Harriet been all cleaned up and wrapped in a blanket before I saw her at all, her father by my side reporting that, “Our baby has so much hair.” There had been a gap between her birth and her life that I was never able to get over, the medical screen never really coming down, and perhaps I’m just coming up with metaphors to explain my failure to process that this child was mine, but there it was. I wanted pictures this time. Of all of it. I didn’t want to miss a single thing.

When Iris was a few weeks old, my computer began to fail again, laptops seeming to have a similar lifespan to the space between my children. But we’d learned our lesson and backed up our photos, so that all of them now live on a portable hard drive. Which means they’re inconvenient to access, but they’re there. And I pulled them out not long ago to prove my case in point

“Words and pictures—survival gear for our stories,” writes Myrl Coulter in her memoir, A Year of Days, and I underlined that part. Survival gear indeed, for when I started looking at photos—hundreds of them—from the days after Iris’s birth, I scarcely recognized any of the moments documented within. At least not at first, but then the memory of these moments started returning to me. Mundane things that would be of no interest to anyone but me, for whom they’re unbearably precious—photos of me lying in bed at home with my children, who were discovering each other as sisters; crazy eyed bloated fat face photos from post-op; breastfeeding pics galore; and even a photo my incision just before the staples came out, because I couldn’t actually see it and was unbelievably curious.

“Words and pictures—survival gear for our stories,” writes Myrl Coulter in her memoir, A Year of Days, and I underlined that part. Survival gear indeed, for when I started looking at photos—hundreds of them—from the days after Iris’s birth, I scarcely recognized any of the moments documented within. At least not at first, but then the memory of these moments started returning to me. Mundane things that would be of no interest to anyone but me, for whom they’re unbearably precious—photos of me lying in bed at home with my children, who were discovering each other as sisters; crazy eyed bloated fat face photos from post-op; breastfeeding pics galore; and even a photo my incision just before the staples came out, because I couldn’t actually see it and was unbelievably curious.

I’d forgotten all of it, which is natural, I suppose, and it’s possible that it’s unnatural to have so much documentation, that it may tax our minds to have so much evidence of… of what? Of life, I suppose. And these photos bring it all back so clearly. Having taken them certainly does not mean that I was any less in the moment (and really, being a mother is to be eternally in the moment no matter how you try to swing it). If it had only been about the moment and not its preservation, those memories would have been lost altogether.

There has been a lot of criticism thrown at my generation, and those younger, for oversharing, for selfies, for self-absorption, and toward mothers in particular for conspicuously mothering on social media. (This is a criticism I was responding to when I resisted baby photos on Facebook so many years ago). But the idea of survival gear frames it all in another way. In her book, Mommyblogs and the Changing Face of Motherhood, May Friedman writes against criticisms that mommy blogs will cause harm to the children who later in life encounter their own childhoods documented online. She writes:

There has been a lot of criticism thrown at my generation, and those younger, for oversharing, for selfies, for self-absorption, and toward mothers in particular for conspicuously mothering on social media. (This is a criticism I was responding to when I resisted baby photos on Facebook so many years ago). But the idea of survival gear frames it all in another way. In her book, Mommyblogs and the Changing Face of Motherhood, May Friedman writes against criticisms that mommy blogs will cause harm to the children who later in life encounter their own childhoods documented online. She writes:

Children are silent witnesses to their own parenting, unable to recall the nuances of their own infancy and early childhood. Indeed, it is arguable that children can only remember parenting as it becomes combative. By reading not only about their mothers’ struggles, but also about their mothers’ obvious love and care, perhaps adult children may find their relationships with their mothers bolstered rather than damaged. Whether the outcomes are positive or negative, mommyblogs allow children to see their mothers as three-dimensional individuals…

This morning when I read of the sudden death of Today’s Parent editor Tracy Chappell, I thought about her post from December, “Why I’m breaking up with my blog,” which is one of the most thoughtful pieces on blogging I have ever encountered. I’m going to be using it in my course going forward. She writes about blogging makes you live your life in a more reflective way, see the world differently, and how blogs are such remarkable records of these lives we live.

This morning when I read of the sudden death of Today’s Parent editor Tracy Chappell, I thought about her post from December, “Why I’m breaking up with my blog,” which is one of the most thoughtful pieces on blogging I have ever encountered. I’m going to be using it in my course going forward. She writes about blogging makes you live your life in a more reflective way, see the world differently, and how blogs are such remarkable records of these lives we live.

Chappell writes, similarly to Friedman:

I hope that, through this blog, they will learn to see me as not just “Mom” but as a woman who had her own things going on—a career, relationships, dreams, struggles, goals—as I was wiping bums and making dinner and gently (oh-so-gently) brushing knots out of hair. I hope they’ll see the value in taking lots of pictures and marking special moments. I hope they’ll understand that parenting is really hard and also has great rewards. I hope they’ll see how much fun we had. I hope they’ll see that I recognized and appreciated their many beautiful, individual gifts, even if they thought I wasn’t paying enough attention at the time. I hope they’ll see how hard I tried. I hope they’ll see how much they were loved. I hope they’ll see how proud I’ve always been to be their mom.

These would be poignant words anyway, but mean so much more now with their writer’s death. What a legacy for her girls, all those posts, which will provide them answers to those questions all of us have about our childhoods, answers that are forever lost to time, confusion, blurry brains. How they will still have this remarkable access to their mother’s voice, even now that she is gone. It will never make up for their loss, but what a gift too, to be able to know who she was. And how profound her love was for them.

All of which underlines my sense that these acts of documentation are some of the most important things we’ll ever do.

May 19, 2015

Four Things That Saved Holiday Monday

1. We went to Kensington Market, and I finally found a copy of This is Sadie by Sara O’Leary and Julie Morstad at Good Egg.

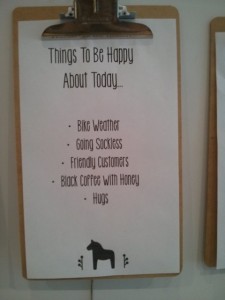

2. We went to Fika, where I had an iced tea latte and baked goods, and this notice was posted. Plus they have an entire wall decorated with repurposed paperbacks.

3. We found a wallet full of cash on the sidewalk and were able to return it to its owner, who was most relieved and had just been about to cancel his credit cards.

4. We went out for sushi, and a family with a 20 month old sat at the booth behind ours. The little girl and Iris spent the entire meal hugging and kissing each other, and by the time the sushi was done, we were all singing songs from Annie.

May 18, 2015

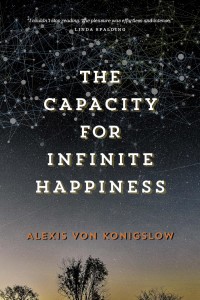

The Capacity for Infinite Happiness by Alexis Von Konigslow

I credit this to living downtown, or maybe there are interesting, creative people everywhere, but I have had some incredible fortune meeting other mothers at the library’s baby time. Most recently, Alexis Von Konigslow whose debut novel is The Capacity for Infinite Happiness, a weird, enthralling, and singularly original book. I was drawn to it by its story of a mathematician, because I love books about math and science, which allow me access to these worlds I’m not otherwise privy to. But I wasn’t as sure about the rest of the book’s description—Harpo Marx, who I wouldn’t be able to tell from Karl, and Passover, when I know as much about the Seder as I do about the Marx Brothers. More over, how do you plot a novel whose points are so divergent, against the setting of a Muskoka lodge, no less? But plotting points is what the book is all about, in terms of math and narrative, drawing connections between ideas, and the pattern that emerges is remarkable.

I credit this to living downtown, or maybe there are interesting, creative people everywhere, but I have had some incredible fortune meeting other mothers at the library’s baby time. Most recently, Alexis Von Konigslow whose debut novel is The Capacity for Infinite Happiness, a weird, enthralling, and singularly original book. I was drawn to it by its story of a mathematician, because I love books about math and science, which allow me access to these worlds I’m not otherwise privy to. But I wasn’t as sure about the rest of the book’s description—Harpo Marx, who I wouldn’t be able to tell from Karl, and Passover, when I know as much about the Seder as I do about the Marx Brothers. More over, how do you plot a novel whose points are so divergent, against the setting of a Muskoka lodge, no less? But plotting points is what the book is all about, in terms of math and narrative, drawing connections between ideas, and the pattern that emerges is remarkable.

It’s the story of Emily who seeks refuge at her family’s lodge in Muskoka, a near century old Jewish resort, after a devastating revelation from her mother and frustration with her PhD thesis. She has been mapping social networks, showing how math can chart the connections between people, and she wants to apply what she’s learned to her own family and the lodge, but the lines aren’t matching up. She’s having trouble untangling the connections, figuring out who came from where in her family’s complicated network, and what exactly happened years ago when her great-great-grandparents arrived in Canada escaping persecution in Russia. Her confusion isn’t mitigated by her grandmother and great-aunt’s cryptic ways with history and storytelling—Emily’s questions are never properly answered. Was Harpo Marx really once a guest at the lodge? What is the real story of her family in Russia? And what was her great-grandmother’s tragic secret?

Emily’s story takes place in 2003, and is countered with chapters from 1933 when Harpo Marx was indeed a guest at the lodge. These chapters are from Harpo’s point of view, which might explain their oddness, their dreamlike sensibility. Though Emily’s story is pretty strange as well, her character as eccentric as her ancestors’. She and her friend Jonah, who she’s known since childhood and has feelings for, begin to care for a pet lamp called Jazzy. A kookiness that might be characteristic of the Marx Brothers infuses the entire narrative. It is all very odd and slightly skewed, and would be off-putting and fey in the hands of a lesser author, but Von Konigslow is very good. There is something so absorbing about the novel’s crafting, how its two parts start to echo each other, a formula that begins to emerge as to how they are connected, and this is the mystery for which we are reading. This project is large and ambitious, and fascinatingly realized—when I got to the end, I was breathless. It was such a pleasure to read this book, which is unlike any I’ve ever read before.

And now I want to go and watch A Night at the Opera.

- Purchase The Capacity for Infinite Happiness from McNally Robinson

- Speaking of connections, I liked Pasha Malla’s piece about whether you should trust a review by a writer’s friend. (A nice thing about having a blog is that I can review books by whomever I like.)

May 18, 2015

Night and Day

Night

We are going through a difficult period. I like framing it this way because it suggests an ending, as opposed to, We are going through a difficult eternity. “It’s just a phase,” we keep saying. “Things will get better,” but we’re beginning to sound less sure of this. It has been so long. Nearly two years since I’ve had unbroken night’s sleep. And since we came back from England, things have been awful. Iris moved downstairs into Harriet’s room to sleep, but her nighttime wake-ups have continued, plus it’s started taking her sometimes up to an hour to fall asleep, she requires us lying down beside her to do so, and then she gets up again at 11, at 1. She won’t settle unless she’s in bed with us, which would be okay (and I’m certainly not going to fight a screaming nearly-two-year-old in the middle of the night) except that then she flops and kicks and pinches my upper arms. It is unpleasant. And last night we had a babysitter booked so we could go out to a movie, but Iris refused to go to sleep. Or she would be asleep until we dared to rise and leave the room, and then her eyes would snap open and there we’d be again. Eventually, I gave the babysitter $20 and told her to go home, because we’d missed the movie. And it seems like the baby is holding us hostage, when I dare to frame the whole thing like a power struggle (which I shouldn’t do—it only makes unpleasant realities worse). We can’t go out together to anything that starts before 9pm, because no one else but Stuart and I has the patience to put Iris to bed, and now that she’s only staying asleep for 2hrs after that (if she goes to sleep at all), the world seems to have shrunk to the size of an acorn. I know that there are far worse problems to have than this one, but perspective can be hard to come by when one is having melodramatic thoughts about being subject to tyranny. Five years ago, I wrote a blog post about baby sleep books called The Trajectory of a Downward Spiral, but the trajectory of this plot is more like a head smashing into a wall. Repeatedly.

Day

But. We have had the most wonderful weekend. A weekend whose wonderfulness is currently under threat as I spend this holiday Monday morose and bereft at the end of Mad Men. The children watched Annie and ate goldfish crackers in Harriet’s room while Stuart and I watched the final episode this morning. It was so absolutely perfect. Overwhelmingly good. I feel about this show like I’ve been immersed in the narrative for six years, swimming around inside it and examining from all angles. I can’t believe it’s over, but then it isn’t really. We rewatched an episode from Season 1 on Saturday night, and it occurred to me that I’ll never really be done with it. But still, I’m sad there is no more to look forward to. So many of my feelings were invested in these characters. It all mattered a lot to me.

But. We have had the most wonderful weekend. A weekend whose wonderfulness is currently under threat as I spend this holiday Monday morose and bereft at the end of Mad Men. The children watched Annie and ate goldfish crackers in Harriet’s room while Stuart and I watched the final episode this morning. It was so absolutely perfect. Overwhelmingly good. I feel about this show like I’ve been immersed in the narrative for six years, swimming around inside it and examining from all angles. I can’t believe it’s over, but then it isn’t really. We rewatched an episode from Season 1 on Saturday night, and it occurred to me that I’ll never really be done with it. But still, I’m sad there is no more to look forward to. So many of my feelings were invested in these characters. It all mattered a lot to me.

On Saturday, we celebrated summer things with a trip to the Wychwood Barns Farmers’ Market and ate delicious food, and delighted in the fact that our children are old enough to play unattended (in mud puddles, no less) while we sit on a park bench. We also delighted in that our children were so thrilled to take the bus to the market, but were also cool with walking home. So many of my plans for this summer are inspired by Dan Rubinstein’s book, Born to Walk, and I appreciate that Harriet is big enough to be venturing further afield on foot, to be discovering her pedestrian legs without (too much) complaining. But there are also wheels, and so after Iris’s nap, she went on a bike-ride. We’re going to shed the training wheels this summer, we’ve resolved, but this is just one more thing we’re not sure about how to teach her to do—along with shoelace tying. After that, we did our planting, mostly flowers because the squirrels thwart our efforts to grow anything more substantial. Some kale and basil, but otherwise impatiens, and suddenly our deck is beautiful again. The silver maple that shades our house and yard in magnificent bloom. There is a hammock set up underneath it.

On Saturday, we celebrated summer things with a trip to the Wychwood Barns Farmers’ Market and ate delicious food, and delighted in the fact that our children are old enough to play unattended (in mud puddles, no less) while we sit on a park bench. We also delighted in that our children were so thrilled to take the bus to the market, but were also cool with walking home. So many of my plans for this summer are inspired by Dan Rubinstein’s book, Born to Walk, and I appreciate that Harriet is big enough to be venturing further afield on foot, to be discovering her pedestrian legs without (too much) complaining. But there are also wheels, and so after Iris’s nap, she went on a bike-ride. We’re going to shed the training wheels this summer, we’ve resolved, but this is just one more thing we’re not sure about how to teach her to do—along with shoelace tying. After that, we did our planting, mostly flowers because the squirrels thwart our efforts to grow anything more substantial. Some kale and basil, but otherwise impatiens, and suddenly our deck is beautiful again. The silver maple that shades our house and yard in magnificent bloom. There is a hammock set up underneath it.

Yesterday, we went on our first ravine walk of what is to be many, as we’ve declared 2015 as #SummeroftheRavines. Once again, this is a plan born of Born to Walk—to explore these wild corners of our city. We didn’t have much of a plan and climbed down into the Rosedale Valley via the path behind Castle Frank Subway Station. Unfortunately, Bayview Avenue cuts off our access to the Don Valley, which we weren’t expecting, so we had to climb back out of the ravine in order to get to where we really wanted to be, and by this point, it was nearly time to quit.

Yesterday, we went on our first ravine walk of what is to be many, as we’ve declared 2015 as #SummeroftheRavines. Once again, this is a plan born of Born to Walk—to explore these wild corners of our city. We didn’t have much of a plan and climbed down into the Rosedale Valley via the path behind Castle Frank Subway Station. Unfortunately, Bayview Avenue cuts off our access to the Don Valley, which we weren’t expecting, so we had to climb back out of the ravine in order to get to where we really wanted to be, and by this point, it was nearly time to quit.

But we had fun and the weather was beautiful, and once again, there are very little complaining. We’d compiled a Ravine Walk Bingo sheet, which gave our walk some incentive, as did the promise of lunch afterwards. We went to the House on Parliament and had the most delicious meal, our first patio of the season. And then back to the hammock. I’ve been reading H is for Hawk all weekend, which is not a great read for the emotionally fragile, I am realizing. But it’s really good, deep and layered, and totally weird. So intense. It is possible my whole family will be relieved when I’m finally completed it.

But we had fun and the weather was beautiful, and once again, there are very little complaining. We’d compiled a Ravine Walk Bingo sheet, which gave our walk some incentive, as did the promise of lunch afterwards. We went to the House on Parliament and had the most delicious meal, our first patio of the season. And then back to the hammock. I’ve been reading H is for Hawk all weekend, which is not a great read for the emotionally fragile, I am realizing. But it’s really good, deep and layered, and totally weird. So intense. It is possible my whole family will be relieved when I’m finally completed it.

Which brings me to right now where I’ve just been delivered lunch. (“Um, if I’d known you were having lunch in bed, I might not have brought you breakfast there.”) And it’s up to me to save this day from my lugubriousness and histrionics. Iris has started being capable of having actual conversations (albeit stilted ones, usually about dogs), which is extraordinary, and clearly her brain is going wild these days. If I’m able to muster perspective, it would be that these development changes are responsible for our sleep woes. If I am able to focus less on the woe. In a few weeks she will be two. Harriet turns six next Tuesday. For our family, the next month and a bit is a season of happy birthdays and anniversaries and so so many reasons for cake. (Another? My sister is having a baby tomorrow.)

Which brings me to right now where I’ve just been delivered lunch. (“Um, if I’d known you were having lunch in bed, I might not have brought you breakfast there.”) And it’s up to me to save this day from my lugubriousness and histrionics. Iris has started being capable of having actual conversations (albeit stilted ones, usually about dogs), which is extraordinary, and clearly her brain is going wild these days. If I’m able to muster perspective, it would be that these development changes are responsible for our sleep woes. If I am able to focus less on the woe. In a few weeks she will be two. Harriet turns six next Tuesday. For our family, the next month and a bit is a season of happy birthdays and anniversaries and so so many reasons for cake. (Another? My sister is having a baby tomorrow.)

It all goes by so fast.

May 14, 2015

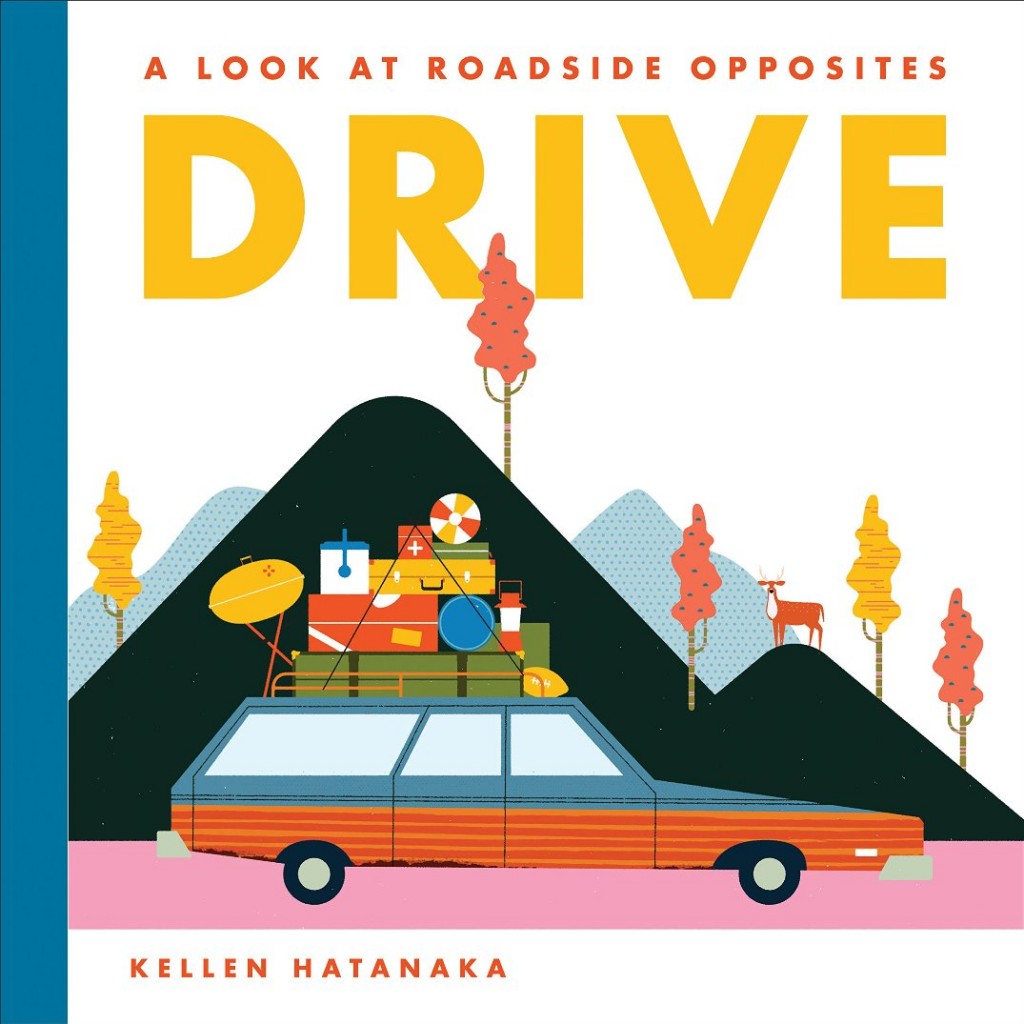

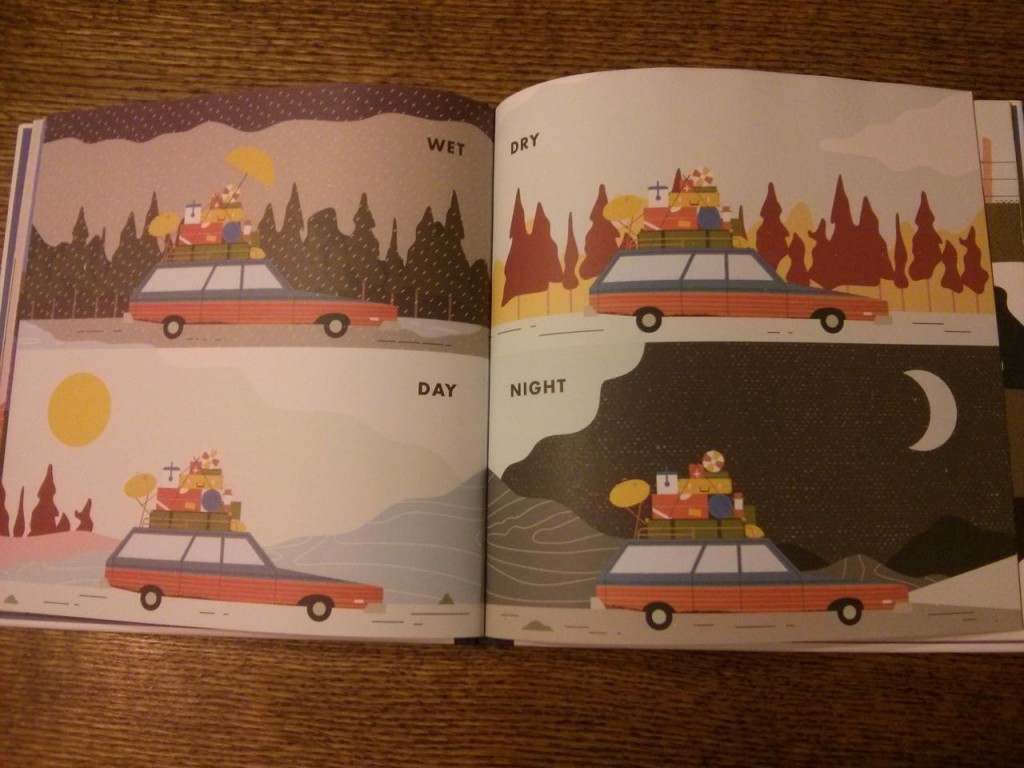

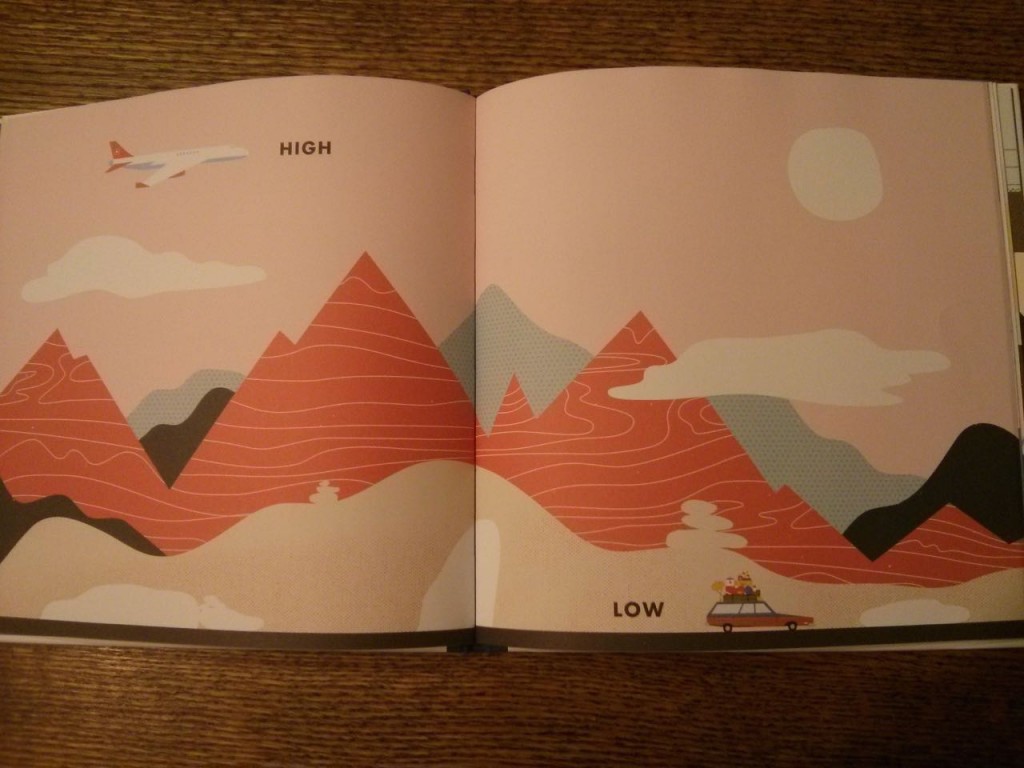

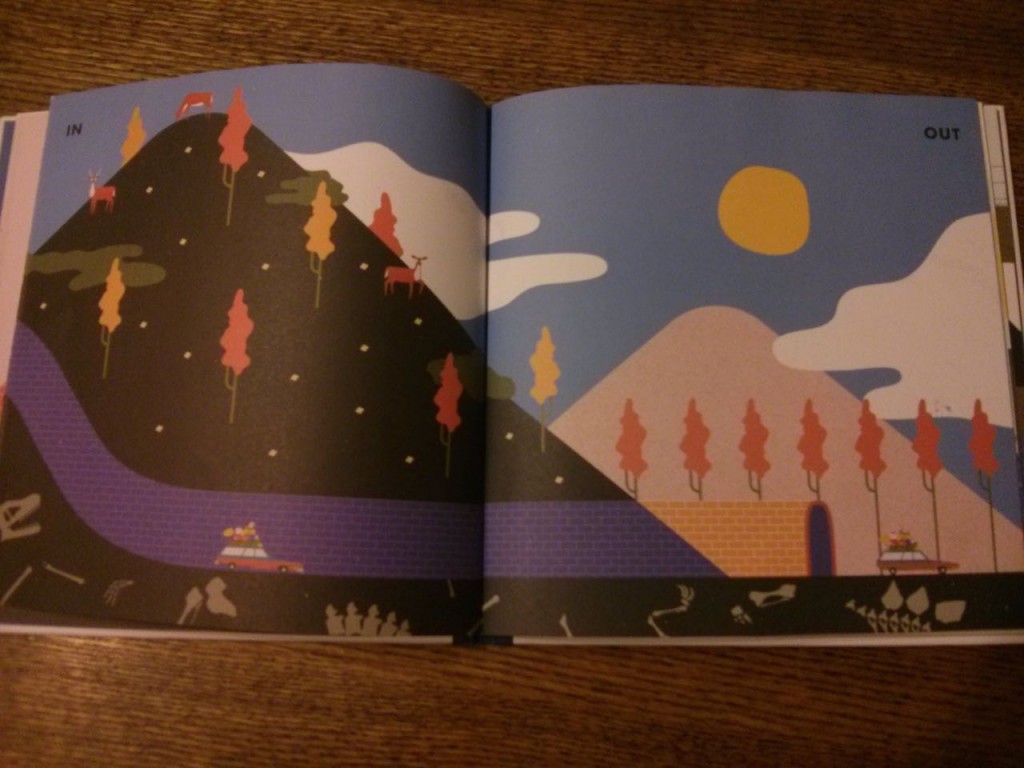

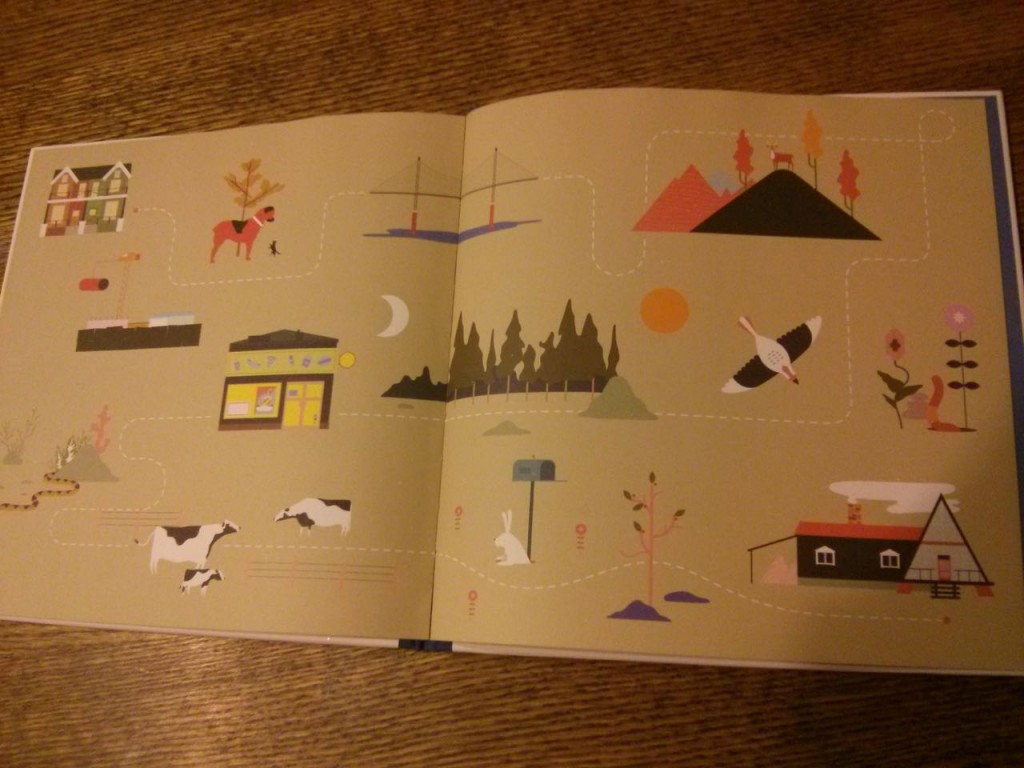

Drive by Kellen Hatanaka

Mad Men ends on Sunday, after years and years, and in tribute to my favourite show, I’ve picked a picture book this week with a similar aesthetic. I think Betty Draper even owned that station wagon exactly. Drive: A Look at Roadside Opposites is the second book by Kellen Hatanaka, whose Work: An Occupational ABC was on my Hipster Picture Book list last year. While this new book is similarly focussed on design, it’s got more of a narrative, and I like it even better than the first one.

Drive is the story of a journey toward a summer holiday, from the city to the country, and therefore a natural setting for I-spying opposites. The car is packed with summer things—a barbecue and beach balls—and we can only imagine the Are We There Yets? before they finally arrive.

But in the meantime, there is looking out the window. Big, small. Above, below. Winding roads and straight ones.

With all of these Don Draper is actually DB Cooper rumours, this page seems particular eerie.

The illustrations are fantastic, full of funny and interesting details. We particularly like the dinosaurs bones under the mountain in the image below. As with his previous book, Hatanaka plays up the unexpected—I love the “Worm’s Eye View” that opens up into a four page spread of “Bird’s Eye View”, the world spread out below, patchwork fields and the winding road, the car viewed straight down on the roof-rack.

At the end, there is a map, a dotted line tracing the journey from place to place and suddenly the whole thing all comes together—the same story from another perspective.

Drive would be an excellent book to take on the road (perhaps along with See You Next Year?), giving a young reader lots to look at when there’s nothing to see out the window, and perhaps inspiring her to look again and closer at the weird and wonderful world whizzing by outside.

- For more on Mad Men and children’s books, see my post, “What Sally Draper Must Have Been Reading“

May 13, 2015

I Can’t Believe It’s Not Better by Monica Heisey

“A Day in the Life of Pinterest” by Monica Heisey is the most ridiculously funny thing ever, plus it’s in The New Yorker, which is pretty darn impressive, and so it was with admiration that I picked up Heisey’s new book, I Can’t Believe It’s Not Better: A Woman’s Guide to Coping With Life. Heisey is a Canadian writer and comedian in her 20s whose column, “The Grown-Ass Woman’s Guide to Life” for the Toronto website, She Does the City, was inspiration for much of her book’s material. Pieces like, “When It’s Time to Switch to Water” (“You Are Considering Peeing Somewhere That Is Not a Bathroom…”) reminded me a lot of being in my 20s, accompanied by “How to Be a Good Roommate” (good tip: “Do Not Leave a Used Pad in a Container of Half-Eaten Poutine…”), and “Working From Home: How to Do It”. Heist’s advice is either markedly sensible (“Some Notes on Etiquette for the Behaviourally Disenfranchised”: “No one thinks your opinion represent those of your employer, so you can probably relax about this”) or tongue-in-cheek, using humour (“What to Wear to Barf at 30,000 Feet”) to satirize a society that positions women as helpless and idiotic, and seems to like us this way. With pieces like, “Good Mistakes Vs. Bad Mistakes: A Fuck Up’s Guide,” Heisey’s book is less a guide to coping than a manifesto to muck through, eat burritos and figure it all out in your own damn time.

“A Day in the Life of Pinterest” by Monica Heisey is the most ridiculously funny thing ever, plus it’s in The New Yorker, which is pretty darn impressive, and so it was with admiration that I picked up Heisey’s new book, I Can’t Believe It’s Not Better: A Woman’s Guide to Coping With Life. Heisey is a Canadian writer and comedian in her 20s whose column, “The Grown-Ass Woman’s Guide to Life” for the Toronto website, She Does the City, was inspiration for much of her book’s material. Pieces like, “When It’s Time to Switch to Water” (“You Are Considering Peeing Somewhere That Is Not a Bathroom…”) reminded me a lot of being in my 20s, accompanied by “How to Be a Good Roommate” (good tip: “Do Not Leave a Used Pad in a Container of Half-Eaten Poutine…”), and “Working From Home: How to Do It”. Heist’s advice is either markedly sensible (“Some Notes on Etiquette for the Behaviourally Disenfranchised”: “No one thinks your opinion represent those of your employer, so you can probably relax about this”) or tongue-in-cheek, using humour (“What to Wear to Barf at 30,000 Feet”) to satirize a society that positions women as helpless and idiotic, and seems to like us this way. With pieces like, “Good Mistakes Vs. Bad Mistakes: A Fuck Up’s Guide,” Heisey’s book is less a guide to coping than a manifesto to muck through, eat burritos and figure it all out in your own damn time.

But there are quizzes. I am a bit too old for Heisey’s book (I am only 35, but her bits on “aging” made me want to say, “Bless…”) but the quizzes took me right back to *my* YM days. When I was ostensibly reading to figure out what kind of person I was (ABC, or D), when the reality was that I wasn’t formed yet, but I knew who I wanted to be, and skewed my answers to get the desired result—which was usually D. Which is to say that we were figuring it out in our own damn time even then, we already know the answers but sometimes it’s just nice to have some affirmation. (Heisey’s quizzes include, “Should You Text Them Back?,” “Should You Eat That?”—all answers point to YES—, and “Which Of The Terrible Fashion Mistakes of My Past Are You?” [“You are my sixteen-year-old self’s attempt at ‘boho-chic’…”].)

There is a tendency among the kind-hearted people of the internet to label anything that’s not a list an essay, which is a little bit misleading (and mortifying when I dash off a blog post, and someone shares it with a reference to the e-word). Most of these pieces are too breezy to be essays exactly, which is not to say that they’re less than, but they lack the depth and precision I expect from a really good essay. The book also suffers a bit in comparison with Lena Dunham’s Not That Kind of Girl (several pieces of which really were essays, as I wrote in my review), similarly structured with lists and doodles. If you hated Dunham’s book, you won’t like I Can’t Believe It’s Not Better, though if you liked it, probably add this one to your list. And while there can never be too many women telling other women that they don’t need to wear uncomfortable underwear in order to get laid, “Some Gentle Advice on Underwear” was reminiscent of Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman (a book whose spirit infuses Heisey’s ethos).

Which is not to say that Heisey doesn’t do her own thing. In fact, she’s her very best when she’s doing her own thing. My favourite pieces in the book were removed from the advice-giving—I laughed out loud on the subway reading “Diary of a Bra,” “On Splitting the Bill and Other Nightmares” is indeed a modern day horror story, the Pinterest piece is so absolutely perfect and smart and hilarious, and also, “How to Make Your Apartment Look Like You Read Design Blogs.” Even if some bits of the book are derivative, they still go massively against the grain of what society is telling women all the time, so it’s not like we’re being saturated by these messages after all. And it’s not like it isn’t incredibly brave still for a woman to stand up and be funny, gutsy, and smart (and vulnerable) in public. Not to mention an inspiration.

So, more of this please. As Heisey writes, “Women speaking to women about being a woman remains one of the best parts of being alive and one of the most important things you can do. Do it often.”

May 12, 2015

A God in Ruins by Kate Atkinson

I’m such an admirer of omniscience, though I’ll admit it’s not for everyone. There are readers for whom omniscience pulls them out of the story, exposing the limits of the fictional universe—that all this is artifice after all—but those very same limits, to me, are the very indicators that there is a fictional universe. It’s the point of reading a book, a whole imagined world to be revealed, and Kate Atkinson is a master at commanding its reins. From her very first book, Behind the Scenes at the Museum, which begins with Ruby Lennox’s conception: “I exist! I am conceived to the chimes of midnight on the clock on the mantelpiece in the room across the hall…”—Atkinson has been part of a grand tradition of English writers (Laurence Sterne, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, etc.) pushing the bounds of narrative to discover just what a novel can hold and the multitudinous ways a story can be told.

I’m such an admirer of omniscience, though I’ll admit it’s not for everyone. There are readers for whom omniscience pulls them out of the story, exposing the limits of the fictional universe—that all this is artifice after all—but those very same limits, to me, are the very indicators that there is a fictional universe. It’s the point of reading a book, a whole imagined world to be revealed, and Kate Atkinson is a master at commanding its reins. From her very first book, Behind the Scenes at the Museum, which begins with Ruby Lennox’s conception: “I exist! I am conceived to the chimes of midnight on the clock on the mantelpiece in the room across the hall…”—Atkinson has been part of a grand tradition of English writers (Laurence Sterne, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, etc.) pushing the bounds of narrative to discover just what a novel can hold and the multitudinous ways a story can be told.

Her last novel, Life After Life, was unabashed in its experimentation. What if, it supposed, a person could go back in her life, over and over again, and have the chance to do over what went wrong before? This was the story of Ursula Todd whose preternatural tendency toward expiration is matched only by her ability to be reborn (“I exist!”) over and over. Her story spans the first half of the twentieth century, encompassing world wars and radical social change. The metaphysical elements of the novel are never clearly delineated—Ursula sort of understands her situation but Atkinson provides no reason for her ability to be reborn and go back in time over and over again. Life After Life is a novel far more concerned with What If? than Why?—to what extent is there predestiny, can we control our fates, what are unintended consequences of that control? Can practice make perfect? What I found remarkable about Life After Life is that Atkinson uses her life-after-life device not just to play tricks, but to build characters too and and develop plot, and how this book of starts comes together to be something altogether whole.

(I am incapable of real criticism of Kate Atkinson. I am simply in awe of her work. But I also thought that Rohan Maitzen’s critical review of Life After Life was excellent, and adds even more texture to a very substantial novel.)

Atkinson’s new novel, A God in Ruins, is not a sequel to Life After Life, she explains in her afterword, but “a companion novel.” It’s the life story of Ursula’s brother Teddy in a version of their family’s life that is slightly different than those portrayed in the first novel. Where Ursula died over and over again, Teddy shows a predilection toward survival, miraculously making it through a career as a WW2 bomber pilot. And it is the war upon which his story hinges—an experience both makes him and destroys him. An experiences that does not become less raw as the war itself fades into history, though those around put it away in the past. “You can only go forward,” is a line delivered again and again in the text, a winky joke at the premise of Life After Life, but also blatantly wrong in the matter of narrative because an author is free to put her story together anyway she likes—forward, backward, and round and round in circles. Posing the questions: what if history never entirely goes away? how does it change as we carry it with us? And how is a conventional existence not unlike Ursula’s in reality: “It felt as if he had lived many lifetimes,” Teddy remembers at one point, and who has not felt this way? What is the cumulation of these lives, these selves? What is the thing that connects them?

The reader follows Teddy through his many lives, which are all lived in the same life—through the trauma of his war experiences (whose violence is unflinching but matter-of-fact), the happy early years of his marriage, his tumultuous relationship with his daughter, Viola, and the injustices she inflicts upon her own children, whom Teddy becomes responsible for. As with Life After Life, there is repetition, details slightly changed, conflicting accounts—reading the novel through a similar metaphysical lens as the previous novel is an illuminating experience. And at the end of the story, Atkinson shows her hand with a twist that shall not be revealed, but it’s wonderful and gut-punching, and demonstrates that we’re in the hand of a master writer. As if you ever had any doubts…

May 10, 2015

Aching testicles, bodacious breasts, and other childhood lessons in anatomy

Image from here.

“My testicles are aching,” my daughter confessed to me the other day, which is the only problem I’ve so far encountered in my experience of having taught her the correct name for anatomical parts. That eventually, one might get mixed up when meaning to say “limbs” and start talking about her balls instead. And maybe this is the danger parents are hoping to avoid, those who pulled their children out of Ontario schools last week in protest of the new sex-ed curriculum. That there are so many body parts and the children aren’t ready, and with everything getting so mixed up, gender fluidity is surely just around the corner. It’s contagious. What else can you expect when it’s scrotums for everybody, and sexual identity is all a slippery slope.

I haven’t actually read the new sex-ed curriculum, because unlike some people, I’m not a total pervert. And I’ve got better things to do than vet school curricula for ways it’s going to warp my child’s mind, because the world is going to warp her anyway, and here is the point where my job as a parent kicks in: I send her into the world and then, when she gets home, together we try to make sense of the mixed messages it’s throwing at her. Like why, for example, in a hyper-sexualized world (ever driven down a highway and looked at a billboard lately?), we are so fearful of teaching our children there is such a thing as sex or that parts of their bodies actually have names.

I can’t do it all on my own though. As Hillary said, it takes a village. From proximity to my body, my daughter has learned about all varieties of skin rash, but that’s only the tip of the anatomical iceberg—there is so much more. And my plan for this education, which I hope will avert much future sextastrophe (the more you know!) involves extra-curricular activities.

My daughter is enrolled at swimming lessons at the university pool, and we strategically avoid the Family Change Room. After her lessons, we head to the Women’s where she has her hair washed surrounded by naked ladies. An invaluable education—how to be subtle, for one thing, and look like you’re not looking, and also how not to pee in the shower, which is mostly “at all”, but if you have to, don’t announce it while you’re doing it.

Mostly, her post-swimming showers are a lesson in the exquisiteness of womankind. Women of all shapes, sizes, and colours, gloriously naked, just having finished some activity that makes her body strong. Beautiful, all of them, stunning in their variety. Contrary to what a series of lingerie ads might have you suppose, there are so many ways to have a body. No two alike. Shockingly, almost all of them have pubic hair. And the bodies themselves are big and small, curved and slender, muscular, wiry, always amazing (because it’s ill-fitting clothing that fails to flatter the body, I find. The body itself requires no flattery at all). Bums, boobs, tummies and, yes, limbs. We’re both kind of mesmerized. What a sorority. You’re a woman, albeit a small one, and you’re part of this, a body-haver. It’s the most incredible way to put the whole thing in perspective.

Of course, it’s not all naked utopia. You’ve got the woman who’s squeezing her ass-zits in the shower, and the other who is shaving her thighs, which is kind of gross because her pubes are flowing across the tiles. But that bodies are disgusting is an important lesson too. And that they’ve got functions, beyond their ability to be stuffed into a bikini and be beholden to the male gaze. We’re getting all of this in the Woman’s Locker Room and I’ve got to shut up about this, or swimming lessons are going to up their fees. And even if they did, I’d probably pay the difference. There is awkwardness, yes, and the pain of aching testicles, but it’s the best basis for sex education that I can imagine—the knowledge our bodies are gorgeous and amazing—and knowing this we’re better prepared to handle whatever this curious world hands us next.