June 22, 2015

A Pitying of Doves by Steve Burrows

Steve Burrows’ first Birder Murder Mystery, A Siege of Bitterns, was one of my favourite reads of 2014, a smart and absorbing novel that introduced the enigmatic Chief Inspector Dominic Jejeune, reluctant police superstar, avid birder and expat Canadian on the Norfolk coast. I loved the premise, was drawn in by the character, and admired the intelligence and fun of Burrows’ writing—and that the mystery’s solution hung on a point of grammar. So ever since I’ve been looking forward to the second book in series, A Pitying of Doves.

Steve Burrows’ first Birder Murder Mystery, A Siege of Bitterns, was one of my favourite reads of 2014, a smart and absorbing novel that introduced the enigmatic Chief Inspector Dominic Jejeune, reluctant police superstar, avid birder and expat Canadian on the Norfolk coast. I loved the premise, was drawn in by the character, and admired the intelligence and fun of Burrows’ writing—and that the mystery’s solution hung on a point of grammar. So ever since I’ve been looking forward to the second book in series, A Pitying of Doves.

And I was not disappointed. Book two finds more bird-related murder and mayhem in Norfolk (and really, how can Jejeune ever doubt that he’s where he’s meant to be, a place with not one but two murders in which his ornithological background is useful). The book begins with a rather gruesome scene at a bird sanctuary where a researcher is found dead beside the body of a Mexican consular official. The powers that be are eager to have the diplomat found innocent of all wrongdoing in the interesting of international relations, but nothing is that simple. Is the case connected to two missing Turtle Doves from a local private aviary whose Mexican owner mysteriously vanished years ago? And what about the bird carver whom neither Jejeune nor his girlfriend Lindy trust completely? Meanwhile, Jejeune’s partner, Danny Maik, is obvious to love right in front of him, and he’s grappling with his own problems. With twists, turns, and plenty of peril (including a dramatic scene on a cliff face), Burrows plots his way to the finish and Jejeune triumphs again. But does the triumph even matter to him? And what’s with the apprehension by officials in St. Lucia? What ghosts are our birding hero still running from?

Burrows is beginning to fill out Jejeune’s backstory, which was tantalizingly alluded to in A Siege of Bitterns. I feel as though this is a series just begging for a prequel. And while the novel requires a certain suspension of belief—a few twists were the result of very convenient coincidences, and does it really seem possible that everything relates back to birding—it was a fun, smart and satisfying read just like its predecessor. Its a novel with a sense of humour too—the birding motif is tongue-in-cheek when it needs to be. But with enough depth and intrigue via great characterization that the story is as meaningful as it is a pleasure.

June 21, 2015

Where books go to die

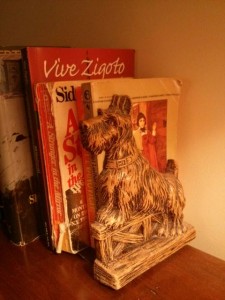

In monumental news, we spent a night away from our children this weekend for the first time in three years on the occasion of our 10th anniversary. They stayed with my mom while we embarked upon a getaway to a nearby resort with an unpretentious rustic feel. We had a wonderful time and it was not so rustic and unpretentious that I didn’t get to drink wine a jacuzzi tub, but the bookishness was extraordinary in its awfulness. There were books everywhere, and it was like they’d cleared out the dregs of every church basement book sale ever. There was a book called How to Get Things Cheap in Toronto that was published in 1977. I was pleased to find a Sidney Sheldon paperback in our room, because he was one of my formative novelists. So many hideous hardbacks. We also had two books by a novelist called Susan Howatch whose garish dust-jackets intrigued me, and I might have read them if not for the must and that I was happily away with The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson and How You Were Born by Kate Cayley (which is so very good). I was also impressed by the Scottish Terrier bookends. And I’m not even kidding.

In monumental news, we spent a night away from our children this weekend for the first time in three years on the occasion of our 10th anniversary. They stayed with my mom while we embarked upon a getaway to a nearby resort with an unpretentious rustic feel. We had a wonderful time and it was not so rustic and unpretentious that I didn’t get to drink wine a jacuzzi tub, but the bookishness was extraordinary in its awfulness. There were books everywhere, and it was like they’d cleared out the dregs of every church basement book sale ever. There was a book called How to Get Things Cheap in Toronto that was published in 1977. I was pleased to find a Sidney Sheldon paperback in our room, because he was one of my formative novelists. So many hideous hardbacks. We also had two books by a novelist called Susan Howatch whose garish dust-jackets intrigued me, and I might have read them if not for the must and that I was happily away with The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson and How You Were Born by Kate Cayley (which is so very good). I was also impressed by the Scottish Terrier bookends. And I’m not even kidding.

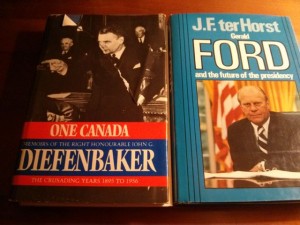

I’m really not. Not being snarky either. I love book collections like this, shelves packed with books that almost nobody wants to read. Where else in the world are you going to find a John Diefenbaker memoir beside a book called Gerald Ford and the Future of the Presidency? There’s nowhere else in the world anymore where such books belong. They’re kind of there for the decor really, but so unpretentiously, attractively faded like the armchairs. Somebody’s fancy, perhaps, but probably not. And I love that nobody even cares about that. I love how far such a collection would force you to read outside the lines, were you to arrive there otherwise bookless. And I think we’ve completely found the place where old books go to die, but it’s such a nice place. What an afterlife. Today’s literary wunderkinds could only hope for such a fate.

I’m really not. Not being snarky either. I love book collections like this, shelves packed with books that almost nobody wants to read. Where else in the world are you going to find a John Diefenbaker memoir beside a book called Gerald Ford and the Future of the Presidency? There’s nowhere else in the world anymore where such books belong. They’re kind of there for the decor really, but so unpretentiously, attractively faded like the armchairs. Somebody’s fancy, perhaps, but probably not. And I love that nobody even cares about that. I love how far such a collection would force you to read outside the lines, were you to arrive there otherwise bookless. And I think we’ve completely found the place where old books go to die, but it’s such a nice place. What an afterlife. Today’s literary wunderkinds could only hope for such a fate.

June 19, 2015

Butterfly Park by Elly Mackay

I bought Butterfly Park because Sara O’Leary named it as a hypothetical Sadie Summer Read in our 49th Shelf interview, and then I saw it featured on the wonderful children’s literature website, kinderlit. When I finally laid eyes on on the actual book, it was inevitable that we’d own it. It’s beautiful, magical, and infused with the same sense of wonder that is so compelling about This is Sadie.

The story is simple, and not really ground-breaking: a young girl moves from the lush countryside to a dank and dirty town. The one spot of hope is a park beside her house with an elaborate gate and a sign reading, “Butterfly Park.”

But when the girl goes inside, there is not a butterfly to be found. With the help of other children in the neighbourhood, however, the girl embarks upon a quest to make Butterfly Park live up to its name, and the whole community is awakened in the process.

While the story is pretty basic, the book’s depth comes from its illustrations—literal dept and otherwise. Mackay’s images are extraordinary, paper cut-outs painted and assembled in three dimensional scenes in a wooden frame, and then photographed. There is a an old-fashioned Victorian postcard feel to the children she has painted, except that her children show diversity in their skin colours, which is wonderful. And it’s remarkable to consider that her exquisite detail has been rendered in paper cut-outs—I’m especially fond of her clotheslines, garden gnomes, and all the other perfect little things in the corners of her scenes.

My favourite thing about Butterfly Park is MacKay’s rich and warm use of light, which indicate the passage of time and time of day. Her glowing oranges and yellow are beautiful to behold and add event more texture to this images, if such a thing is possible.

I also appreciate how my daughter’s response to reading the book was a very This is Sadie-like move to go out and make something. “Mom, I need the scissors,” she said, and got to work cutting out bits of paper in a way she hadn’t done since she was three (which, if you are a parent, you will know is most children’s peak cutting-out-bits-of-paper period). I also love how the book’s conclusion underlines things I’ve been thinking about lately about gardening as community building.

Plants need roots to grow, indeed.

June 17, 2015

Nobody ever believes in love

Nobody ever believes in love. I certainly didn’t. Ten years ago right now, the day before my wedding, when my husband-to-be and his mum were running errands in their town, they ended up waiting for ages at the bank. I was at home waiting for them to come back, and when they didn’t, I started to feel sick to my stomach. It was terrible. I was convinced that halfway there they’d had a heart-to-heart, and Stuart had confessed he didn’t want to go through it all, and now they were driving around in circles trying to come up with the kindest way to let me down. I was convinced of this not because I lacked faith in Stuart or in our relationship, but because it just seemed too easy, too simple, too lucky, that our wedding, our marriage would transpire. Because there were no flies in the ointment (except that we were both of us unemployable, and neither descended from moneyed stock, sadly).

Nobody ever believes in love. I certainly didn’t. Ten years ago right now, the day before my wedding, when my husband-to-be and his mum were running errands in their town, they ended up waiting for ages at the bank. I was at home waiting for them to come back, and when they didn’t, I started to feel sick to my stomach. It was terrible. I was convinced that halfway there they’d had a heart-to-heart, and Stuart had confessed he didn’t want to go through it all, and now they were driving around in circles trying to come up with the kindest way to let me down. I was convinced of this not because I lacked faith in Stuart or in our relationship, but because it just seemed too easy, too simple, too lucky, that our wedding, our marriage would transpire. Because there were no flies in the ointment (except that we were both of us unemployable, and neither descended from moneyed stock, sadly).

“Marry a good man,” answered Anne Enright in this weekend’s Globe and Mail Books to the question, “What the best advice you’ve ever received?” And I did. Ten years on, it only becomes more clear.

I still don’t believe it totally. Perhaps the problem is that I’ve spent my life reading fiction. It occurred to me as I contemplated writing this post that it would be very novel-like (i.e. the way that life goes) if three days from now by husband told me he didn’t love me anymore and was leaving me for somebody whose forehead wasn’t perma-wrinkled and rashy, maybe some whose abs were less rippled than mine (by which I mean rippling in the breeze, of course). Years ago, I read a line from an article about divorce—”‘Barring some catastrophe,’ Bonnie says, placing a hand on her husband’s khaki-clad knee. ‘We are going to have a successful lifelong marriage.'”—and it turned out I knew of Bonnie, though by the time I came across the article, she was already divorced. I don’t know if there was any catastrophe. But still. I am so fascinated by declarations of undying love and gratitude in the acknowledgements pages of backlist books by authors whom I know to be no longer attached. “To Pablo, my everything. It begins and ends with you.”

So I don’t know. But here is what I do know: ten years ago I married a good man, and I love him more and more all the time. And more than that, I like him. He is my choicest companion for any endeavour, from the Valentines we spent in the hospital ER while our three-year-old had an enema to dreamy vacations far across the sea. He is kind and patient and fun, smart and interesting. Everything good that I have ever made has been co-conspired by him. He is supportive, hilarious, imaginative, good, hard-working, generous, and adorable. I am absolutely nuts for him, and really, I could adjectivise him all day. And he loves me back. He doesn’t just say it, but he shows it. Simple, easy, lucky. Can you see why I’m not sure?

I worry about writing down these things in case I come across as more irritatingly smug than I usually do, if such a thing is possible. But in not writing it down, a different kind of narrative takes hold. The kind that presumes that it is not possible to be married to someone for ten years and to love them more and more all the time. That marriage is a sham, it doesn’t work, that everyone is cheating, or longing to. Which is so far from my experience, in which my marriage is the bedrock of my entire life. Solid ground, I think. The surest thing I know.

Or do I? I think so. But it’s a kind of faith, marriage, believing in somebody else, believing in oneself even. That’s all it is, but then it’s everything. It’s all we’ve got, but then there’s all we’ve got—with a focus on the muchness. Ten years ago, we had no idea. We were two weeks away from moving to Canada, making a start here, I was embarking on graduate school, Stuart applying for permanent residency. The year we got married and the year after that, we lived on groceries from No Frills, $50 a week, mostly chickpeas because we couldn’t afford meat, and things made from soup mixes because we didn’t know how to cook. But we learned. It was such a long time ago.

But things started to happen, the way they do when you start leaving your twenties behind. We figured out what we wanted to do and how to do it. We decided what our priorities were going be. It wasn’t all uphill—there were job losses, plenty of failure and disappointment, stupidity, illness, and mistakes. But all these things are better weathered together, and we’re better for them. Better for having kids too, our amazing daughters who are even harder to believe in than love is, because how can the world really be capable of such miracles as that? Life begetting life, first principles, but I don’t get it at all. All this extraordinary amazement at the most ordinary things, and when I look back on the last decade it overwhelms me. It makes me think there is no such thing as ordinary after all.

But things started to happen, the way they do when you start leaving your twenties behind. We figured out what we wanted to do and how to do it. We decided what our priorities were going be. It wasn’t all uphill—there were job losses, plenty of failure and disappointment, stupidity, illness, and mistakes. But all these things are better weathered together, and we’re better for them. Better for having kids too, our amazing daughters who are even harder to believe in than love is, because how can the world really be capable of such miracles as that? Life begetting life, first principles, but I don’t get it at all. All this extraordinary amazement at the most ordinary things, and when I look back on the last decade it overwhelms me. It makes me think there is no such thing as ordinary after all.

You never know what’s around the corner, though I think that’s a blessing far more than a curse. “To me, the grounds for hope are simply that we don’t know what will happen next,” writes Rebecca Solnit in her essay, “Woolf’s Darkness,” which is also an epigraph of my novel. (The other epigraph is from Harriet the Spy.) And while I could never have forecasted the past ten years in my wildest dreams, I think I would have hoped for them, if I’d dared to. For our incredible fortune, by which I mean Stuart and me, and that we found each other at all in a world so big and swarming with other people.

June 16, 2015

Making the world more beautiful…

Speaking of Miss Rumphius, we’ve been lucky enough to find a way to make the world a more beautiful place this summer. We live in one of those annoying (if you’re driving and want to get anywhere quickly) downtown neighbourhoods—literally a five-minute walk from where Jane Jacobs lived—in which the streets only partway belong to cars, and a one-way system has turned side streets into a maze. The one-way streets are indicated by concrete planters that block access to the road, but which haven’t been maintained regularly so that more than a few of them have been filled with weeds and garbage in recent years. Until this year, however, when the neighbourhood residents association went looking for people to “adopt” planters, and we volunteered. We didn’t even have to do the hard work. Another neighbour dug up the weeds, filled the planter with new compost, and planted a shrub.

Speaking of Miss Rumphius, we’ve been lucky enough to find a way to make the world a more beautiful place this summer. We live in one of those annoying (if you’re driving and want to get anywhere quickly) downtown neighbourhoods—literally a five-minute walk from where Jane Jacobs lived—in which the streets only partway belong to cars, and a one-way system has turned side streets into a maze. The one-way streets are indicated by concrete planters that block access to the road, but which haven’t been maintained regularly so that more than a few of them have been filled with weeds and garbage in recent years. Until this year, however, when the neighbourhood residents association went looking for people to “adopt” planters, and we volunteered. We didn’t even have to do the hard work. Another neighbour dug up the weeds, filled the planter with new compost, and planted a shrub.

And then it was over to us, and one day in May we planted alyssum and two lavender plants. We probably should have been more strategic and creative about what to plant, but we were keen and impulsive, so went for it. Happily, the flowers have spread and the garden is lovely now, and when we walk by on our way to school every day, our children bid the planter, “Good morning!” Every evening after dinner we head down the street with our watering cans and give the plants their drink.

There is also now a palm plant in the garden that looks strange and out of place. One day I arrived to water the planter, and someone had left it there for us, quite deliberately, it seemed, the bulb nicely preserved. Now, I’ve heard of people stealing plants from gardens but not so much anonymously bestowing them, and so in order to encourage such behaviour I planted the bulb. Community spirit and everything. I don’t know who gave it to us (or what the plant is!), but I do know that taking care of our planter has connected us with our neighbours in the most fantastic way. We’ve met people out-and-about while we’ve been watering, and heard from others who appreciate the cleaned-up planter and have volunteered to do the watering while we’re on vacation this summer.

There is also now a palm plant in the garden that looks strange and out of place. One day I arrived to water the planter, and someone had left it there for us, quite deliberately, it seemed, the bulb nicely preserved. Now, I’ve heard of people stealing plants from gardens but not so much anonymously bestowing them, and so in order to encourage such behaviour I planted the bulb. Community spirit and everything. I don’t know who gave it to us (or what the plant is!), but I do know that taking care of our planter has connected us with our neighbours in the most fantastic way. We’ve met people out-and-about while we’ve been watering, and heard from others who appreciate the cleaned-up planter and have volunteered to do the watering while we’re on vacation this summer.

It’s only June, but we’ve already got a best-part-of-our-summer-so-far. We really can’t walk past our planter without Iris sticking her nose into the lavender. It’s just about that point in the season where nature explodes with fecundity, so we’ve got weeding to do and the flowers are spreading fast. And I love that this experience is teaching my children about community involvement, how gardening can be revolutionary, about simple biology, and they’re learning responsibility too—which is important because we’re never ever getting a pet (no way!). They don’t even feel ripped off (yet) that instead of a pet, they’ve got a concrete box that stops traffic, but of course it’s so much more than that, as Jane Jacobs herself would attest.

It’s only June, but we’ve already got a best-part-of-our-summer-so-far. We really can’t walk past our planter without Iris sticking her nose into the lavender. It’s just about that point in the season where nature explodes with fecundity, so we’ve got weeding to do and the flowers are spreading fast. And I love that this experience is teaching my children about community involvement, how gardening can be revolutionary, about simple biology, and they’re learning responsibility too—which is important because we’re never ever getting a pet (no way!). They don’t even feel ripped off (yet) that instead of a pet, they’ve got a concrete box that stops traffic, but of course it’s so much more than that, as Jane Jacobs herself would attest.

June 14, 2015

Street Symphony by Rachel Wyatt

“‘This is what I want,’ he heard a woman saying. ‘That’s what I want.’ She seemed to be addressing the world at large. When he came closer, he saw she was pointing at a forty-inch flat screen TV in the store window.” –from “Caffe Italia”

“‘This is what I want,’ he heard a woman saying. ‘That’s what I want.’ She seemed to be addressing the world at large. When he came closer, he saw she was pointing at a forty-inch flat screen TV in the store window.” –from “Caffe Italia”

Nothing is ever quite what it seems in Rachel Wyatt’s new short story collection, Street Symphony. Everybody has a secret life, or else a secret grudge. Bodies fall from rooftops on quiet streets, mothers monitor their adult sons’ email, the woman furtively taking notes at the bar has her own agenda, and then there’s the character walking around town holding a sign asking, “Are you content to be nothing?” Disturbing the quiet of leafy streets has been what Wyatt’s been up to for the last forty years, with novels like The Rosedale Hoax (1977), a satiric comedy set in Toronto’s tony neighbourhood. In Street Symphony, Wyatt’s voice and point of view are just as strong and distinctive.

What that point of view is exactly depends on where one is standing. Or sitting, in the case of the story, “Falling Woman,” in which a character happens to choose a different seat in her living room in which to drink her coffee and read her paper one morning, and thereby observes somebody falling out of the sky. Her usual chair, and she would have missed it. And usual chairs populate the “Caffe Italia” story, which is a microcosm of the collections, in which early morning regulars in a coffee shop tell themselves stories of other people’s lives—and of their own. These are stories about the infinite number of ways that we brush up against each other, but how much we get wrong in the process of knowing. How we are each of us alone, connected only to each other, to paraphrase a line from Marina Endicott’s Close to Hugh, which makes an interesting complementary read to this one. How Wyatt’s characters see the world and each other depends on which direction each one is facing, and perhaps whether they’ve got their curtains closed or open, and all manner of other details.

Wyatt is a tricky writer, her narratives rushing forward and trusting their reader to keep up and to follow the twists and turns of plot and dialogue. Characters aren’t introduced but just appear in full force and action, and we’re to put the pieces together to find out who they are just as those characters discern the lives of the people they encounter in their own circles. Some of these stories will invite a reread upon finishing, and even then, not all the details will be clear. Mysteries remain, secrets kept, puzzles unresolved. Wyatt uses elements of intrigue as she did in her 2012 novel Suspicion, not always to full effect here, but still they keep the stories interesting. There are 17 in this collection and they don’t blend together, but have a cumulative force, building like into symphony of the title, layers of city life. And a few satirical suburban cul-de-sac stories reminded me of Zsuzsi Gartner’s Better Living Through Plastic Explosives, so we’re not just talking about the downtown core.

June 12, 2015

Better late than never

I don’t know that much about irises, except that we’ve had them blooming in our front garden in previous years. The year Iris was born, they were out on her due date, though by her birth date (two weeks later) they’d already been and gone. But this year, while there have been irises throughout the neighbourhood for weeks now (just around the time the lilacs peaked), our garden hasn’t yielded a single one. Where had the irises gone, I wondered? But then this morning on our walk to school we realized that the strange spiky stalks in the middle of the garden had been irises all along—just in hiding. It turns out that we really don’t know much about irises at all, until they spring into bloom. Which is happening a few weeks late this year because our garden is north-facing and mostly always in the shade, I think. But happening nonetheless, because by school pick-up, the flowers had opened up. Better late than never.

I don’t know that much about irises, except that we’ve had them blooming in our front garden in previous years. The year Iris was born, they were out on her due date, though by her birth date (two weeks later) they’d already been and gone. But this year, while there have been irises throughout the neighbourhood for weeks now (just around the time the lilacs peaked), our garden hasn’t yielded a single one. Where had the irises gone, I wondered? But then this morning on our walk to school we realized that the strange spiky stalks in the middle of the garden had been irises all along—just in hiding. It turns out that we really don’t know much about irises at all, until they spring into bloom. Which is happening a few weeks late this year because our garden is north-facing and mostly always in the shade, I think. But happening nonetheless, because by school pick-up, the flowers had opened up. Better late than never.

June 11, 2015

Harriet, You’ll Drive Me Wild by Mem Fox and Marla Frazee

Okay, can we just stop for a moment while I tell you how I worship at the feet of Marla Frazee‘s entire career? The woman behind some of the great picture books ever—Everywhere Babies, The Seven Silly Eaters, and All the World. Her own books too—Roller Coaster and The Farmer and the Clown. Her images are so vibrant, complex, textured, diverse, her world so detailed, her babies so perfect, and her toddlers so perfect…ly devious. I love her. I love her. I do.

I read somewhere once (or else I dreamed it?) that Marla Frazee was not the original illustrator for Harriet You’ll Drive Me Wild, and that there exists somewhere a completely different edition of this book. I am unclear as to the veracity of this rumour not just because I can’t find a single shred of evidence supporting it, but more because it seems unfathomable. (Update: but it’s true! The book was first published in 1986 as Just Like That, illustrated by Kilmeny Niland.)

My neighbours gave me their old copy of this book (the 2003 edition) when my Harriet was three weeks old. I remember sitting in the chair by the window, the scene of innumerable struggles to get the baby to latch, and how here was a book very different than the others we’d been reading in that storm. Different from the new parenting books I’d already filled with my manic marginalia, and different from the baby board books with their saccharine endings (which were somehow always about going to sleep. I wondered, when was that part going to happen?). Here was a book that gave me a glimpse of the future, of a time in which my new baby might not be small enough to tuck in neatly across my chest as we napped on the couch—shocking. A glimpse of a child-to-be, full of energy, beans and mischief.

Where Fox’s Harriet was once my future, six years later, she’s now the past. The character is about three, I think, not intending any trouble (which, according to the text, always happens “just like that”). Frazee’s images show another reality, however, of squirms, experiments, curiosity, contortions and shenanigans—but still, she can’t help herself. “Harriet Harris was a pesky child. She didn’t mean to be. She just was.”

There are so many things I love about this book. First, that it’s Mem Fox, whose work has been so essential to my happiness as a parent. (Read Where is the Green Sheep and not be happy. I dare you.) Second, it’s a literary Harriet, and we love these. Third, that it depicts a very realistic mother, a bit frumpy and struggling to get her own things done while her daughter thwarts her at every turn. (I imagine that between the pages, she is ignoring her daughter and scrolling through Twitter.) And shows that a mother can get angry (for good reason) but that this is okay. Things—people and pillows—can explode, but that doesn’t mean that it can’t be made all right again.

But the foremost reason I love this book is because of the text, and how the lines build on one another along with the mother’s frustration. She begins with her patience tested, saying (because she doesn’t like to yell), “Harriet my darling child. Harriet, you’ll drive me wild.” And that added on to that by the end is, “Harriet, sweetheart, what are we to do? Harriet Harris, I’m talking to you.” Delivered in harassed mother voice. The alliteration of the name is delicious to say, along with the rhyme. I love the consternation.

Reading the part of a mother in a book is rarely quite so nuanced and interesting.

June 10, 2015

Iridescent comes from Iris

From Between You and Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen, by Mary Norris:

From Between You and Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen, by Mary Norris:

“Etymology” is from the Greek and means the study (logia) of the “literal meaning of a word according to its origin” (etymon). (Not to be confused with “entomology,” the study of insects [entomon].) It can be a huge help n spelling. For instance, people sometimes misspell “iridescent.” It’s a trick that often appears on copy-editing tests. Webster’s Collegiate supplies this enthusiastic definition for “iridescence”: “a lustrous rainbowlike play of colour caused by the differential refraction of light waves (as from an oil slick, soap bubble, or fish scales) that tends to change as the angle of your view changes.” Rather than just try to memorize the spelling, if you look at the etymology—study the entrails of the word—you find that “iris, irid” is a combining form that comes from the Greek Iris, the goddess of the rainbow and the messenger of the gods. Wow! Like Webster, I could go off the deep end in finding significance in this: it seems like magic—a word that appeared in Homer’s Iliad and that we associate with Noah’s ark (the rainbow), and with optimism and promise, connects with puddles in Cleveland that I marveled at as a girl (there was a lot of grease in the puddles in Cleveland) and an indelible image from the opening pages of The Catcher in the Rye, in which Salinger has Holden remark on the “gasoline rainbow.” Anyway, once you know that “iridescent” comes from Iris, you’ll never spell it wrong.

(Am reading this book on the recommendation of Ann Patchett, and enjoying it very much. Even the parts without irises.)

June 10, 2015

My Best Books of the Year (so far!)

Nearly midway through the year, I can say that 2015 has yielded some wonderful books. And while the difficult thing about having a mind is that details fall out of it as time passes, a blog can counter that. So let’s remind us both of the best things I’ve read this year (so far!) and perhaps some of the titles can spur on your own summer reading list.

The Devil You Know, by Elisabeth de Mariaffi

The Big Swim, by Carrie Saxifrage

Born to Walk, by Dan Rubinstein

Welcome to the Circus, by Rhonda Douglas