April 23, 2016

The M Word: Kerry Clare on Motherhood and Abortion

This is the fourth in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From previous weeks: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“; “Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self”; Dear Me, by Nicole Dixon.

**

My essay for The M Word was called “Doubleness Clarifies” (you can read it online here) and I wrote it over four mornings during one week in July 2012 while perched in the rafters of the Wychwood Library—the most terrific vantage point. Harriet was three years old, and it was the first time she’d ever been in childcare—a city-run day-camp managed by a woman I loved who ran the creative play sessions we’ve been attending at the Hillcrest Community Centre since Harriet was one. I’d dropped her off and it was the first time she’d ever been anywhere without me, and I had all this time. Three whole hours. And so I rushed up the street to the library, settled into a carrel, and got to work, headphones plugged into my ears playing Carly Rae Jepsen on repeat.

My essay for The M Word was called “Doubleness Clarifies” (you can read it online here) and I wrote it over four mornings during one week in July 2012 while perched in the rafters of the Wychwood Library—the most terrific vantage point. Harriet was three years old, and it was the first time she’d ever been in childcare—a city-run day-camp managed by a woman I loved who ran the creative play sessions we’ve been attending at the Hillcrest Community Centre since Harriet was one. I’d dropped her off and it was the first time she’d ever been anywhere without me, and I had all this time. Three whole hours. And so I rushed up the street to the library, settled into a carrel, and got to work, headphones plugged into my ears playing Carly Rae Jepsen on repeat.

It was a pivotal time in our family life. Harriet would be starting playschool in September, and I was planning on becoming pregnant again around the same time. The shock of new parenthood had worn off and we’d finally found our groove as a family of three. The pieces of the universe were reassembled and were figuring out the way forward. And now I was putting together an anthology about motherhood, because it seemed I had a knack for telling its truths. And the truth that I wanted to tell about it now was how fundamental choice had been to my whole experience, and how for me the experiences of motherhood and abortion were irrevocably connected.

I’ve written before about learning to talk about my abortion, a process in which my essay from The M Word played an enormous role. “It is only recently, and with a great deal of practise, that I have been able to say ‘abortion’ in conversation without dropping my voice an octave and muttering in order for the word to be nearly inaudible” I wrote in my essay, and that’s the only part of it that seems foreign to me now. I remember writing those lines and contemplating that one day I could possibly end up saying “abortion” in front of an entire room full of people, and wondering whether this was possibly the wisest idea. And yet. It turned out I was braver than I ever thought I could be; and that most people are way less hung up about abortion than you’d ever expect; and that there is nothing more liberating than refusing to feel shame. In understanding that you don’t have to apologize for wanting to know your own soul. Writing that essay, putting my name on it and owning it has taught me a lot about not giving fucks, what it means to be steely, and the kind of example of womanhood I want to set for my daughters. It’s made me into the kind of person I always wanted to be.

It helped, of course, that I was pregnant when the book went out for submission, and that I had a wee baby girl sleeping on my chest throughout the fall of 2013 as I edited the book, and that when the book was launched the following spring, I went to author events wearing the baby on my chest. (The night the book launched at Ben McNally books, I read my piece, and then had to strip down to breastfeed in the fiction section, for I’d chosen a book launch dress with a back zip, perhaps not so wise.) It was easier to stand up in front of a room full of people talking about abortion while holding my cute (albeit very bald, especially in retrospect) baby—I felt her presence shielded me from the possibilities of some criticism, and also legitimized my argument because (as I wrote in my essay): “It is possible that no one more than a mother can truly understand just what it is that a woman who has had an abortion has lost and gained.”

I still think that’s true, though I feel now that the baby was unnecessary. And while she made me feel more comfortable saying the word abortion out loud in public, I don’t wish to imply that any woman has more right to do so than another. But, as I’ve said, for me the experiences of abortion and motherhood are so irrevocably connected. It was the one that allowed me the other.

**

Other happenings in the lives of the women of The M Word:

Myrl Coulter’s latest book is A Year of Days. * Christa Couture’s new album, Long Time Leaving, has just been released. * Saleema Nawaz’s novel, Bone and Bread, was a finalist for CBC Canada Reads 2016 * Alison Pick’s memoir, Between Gods, was a national bestseller and a Globe and Mail Best Book of 2014 *Carrie Snyder’s Girl Runner was shortlisted for the Rogers’ Writers’ Trust Prize * Patricia Storms’ latest picture book is Never Let You Go, which was an OLA Best Bet * Sarah Yi-Mei Tsiang’s The Night Children was published in Fall 2015 * and Priscila Uppal’s latest book is the short story collection, Cover Before Striking.

April 22, 2016

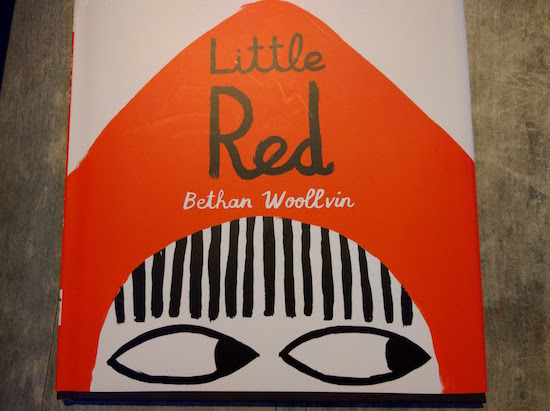

Little Red, by Bethan Woollvin

My big girl blew my mind this week with her “persuasive writing assignment,” about why the book Super Red Riding Hood should win the Blue Spruce Award through the Ontario Library Association’s Forest of Reading Award. “Firstly, it is a feminist book because it has a has a superhero who is a girl,” she wrote in her piece. “Secondly, it is cool and interesting because it has a great superhero. Finally, it is based on a fairy tale and full of suspense.” And of course because the best thing about fairy tales is one can never have too many versions of one, this week we were overjoyed to welcome Bethan Woollvin’s Little Red into the feminist Red Riding canon, a book that won the Macmillan Prize in 2014.

Woollvin’s illustrations reminded of Jon Klassen’s because while her style is very different, her approach is similar in its spareness, and also in how she uses her character’s eyes to provide emphasis to the understated text (which reminded me a lot in terms of rhythm and sentence structure of Mac Barnett’s in Extra Yarn).

And never ever has an illustrator put side-eye to such incredible use—Red Riding Hood’s facial expressions are magnificent.

In the author’s biography, we learn that this story was born out of Woollvin’s own problem with the Red Riding Hood Story when she encountered it in childhood: what kind of a moron would be taken in by a wolf in a nightdress? Surely Red Riding Hood was smarter than that?

And in this story, we see that she is. Red Riding Hood catches onto the Wolf’s preposterous posing as soon as any other smart, courageous girl does, and she comes up with a plan to deal with it on her own terms, no huntsman required. What transpires exactly between them is left up in the air, but we see Red Riding Home afterwards heading home in a wolf-suit—a most terrific homage of Sendak’s Max, I thought. It seems that girls can indeed be superheroes—and they can channel the ferocity of a wild thing too when it suits them.

Girl Power.

April 21, 2016

Light and darkness, dancing together

This morning I dropped Iris off at playschool, and noticed pussy willows in a jar on the counter, which took me back to a scary time we went through through just over three years ago now. It was a time in which I learned that it was possible to navigate life even in the presence of one’s deepest fears, and also that doing so sometimes required errands such as an excursion with shopping list consisting only of a bouquet of pussy willows and a tub of chocolate ice cream. I remember that with the pussy willows, I finally began to feel better, and I think I was thinking of A Swiftly Tilting Planet at the time, but I didn’t pick it off the shelf to get the reference.

This morning I dropped Iris off at playschool, and noticed pussy willows in a jar on the counter, which took me back to a scary time we went through through just over three years ago now. It was a time in which I learned that it was possible to navigate life even in the presence of one’s deepest fears, and also that doing so sometimes required errands such as an excursion with shopping list consisting only of a bouquet of pussy willows and a tub of chocolate ice cream. I remember that with the pussy willows, I finally began to feel better, and I think I was thinking of A Swiftly Tilting Planet at the time, but I didn’t pick it off the shelf to get the reference.

But yesterday morning I was walking to school with my seven-year-old neighbour who’s currently in the middle of A Wrinkle in Time and has the other books in the series before her, and I told her how much A Swiftly Tilting Planet still means to me as an adult. It was the book I picked up in September 2001, after two planes flew into buildings and we wondered if the world as we knew it was entirely gone. I remember the comfort it brought me, the comfort it always has.

But yesterday morning I was walking to school with my seven-year-old neighbour who’s currently in the middle of A Wrinkle in Time and has the other books in the series before her, and I told her how much A Swiftly Tilting Planet still means to me as an adult. It was the book I picked up in September 2001, after two planes flew into buildings and we wondered if the world as we knew it was entirely gone. I remember the comfort it brought me, the comfort it always has.

Mrs. Murry said, “I remember my mother telling me about one spring, many years ago now, when relations between the United States and the Soviet Union were so tense that all the experts predicted nuclear war before the summer was over. They weren’t alarmists or pessimists it was a considered, sober judgement. And Mother said that she walked along the lane wondering if the pussy willows would ever bud again. After that, she waited each spring for the pussy willows, remembering and never took their budding for granted again.

I took it down off the shelf this morning to find the pussy willows paragraph, and realize that I absolutely have to reread this book again. And I considered how fundamental it might have been in cementing my understanding of the cosmos, the world.

Darkness was, and darkness was good. As was light. Light and darkness dancing together, born together, born of each other, neither preceding, neither following, both fully being in joyful rhythm.

April 20, 2016

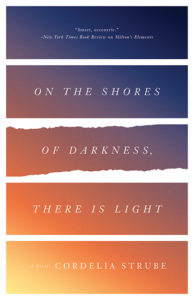

On the Shores of Darkness, There is Light, by Cordelia Strube

Ever since 1964, writers whose protagonists are eleven-year-old girls called Harriet have been taking a serious chance on things. How can one actually pull that off that kind of literary homage? But Cordelia Strube, whose many books include the 2010 Giller-nominated novel Lemon (which was one of my favourite books that year) has absolutely pulled it off. Her Harriet, in On the Shores of Darkness There is Light, is a many-splendored, singular creation, and the novel goes and goes and never falters.

Ever since 1964, writers whose protagonists are eleven-year-old girls called Harriet have been taking a serious chance on things. How can one actually pull that off that kind of literary homage? But Cordelia Strube, whose many books include the 2010 Giller-nominated novel Lemon (which was one of my favourite books that year) has absolutely pulled it off. Her Harriet, in On the Shores of Darkness There is Light, is a many-splendored, singular creation, and the novel goes and goes and never falters.

Harriet lives in an apartment building called the Shangrila, once a luxury high-rise but now a place housing mostly downtrodden seniors and her family since they lost their home in the 2008 economic downturn. Her mother is trying to keep them afloat through under-the-table bookkeeping, with no help from Gennady, her broke criminal lawyer boyfriend in Crocs, or Harriet’s father Trent, avid cyclist who lives with Uma who he met at the farmer’s market and who is currently in the middle of an IVF cycle. And then there is Irwin, Harriet’s five-year-old brother who has hydrocephalous and whose traumatic entrance to the world brought forth the end of Harriet’s parents’ marriage and all semblances of stability in her life. His health remains perilous, with frequent seizures and hospital visits, ever a source of anxiety and preoccupation for their mother, leaving Harriet with a preponderance of freedom that she exploits for her own devices.

Dumpster-diving for materials for her found art projects, charging her elderly neighbours for runs to the convenience store, and hanging out with her teenage neighbour, Darcy, and losing her scattered grandmother at the Scarborough Town Centre, Harriet has her own agenda, which ultimately involves her dream of escaping it all and getting away to a rural retreat far away in Algonquin Park, living alone by a lake and painting much like Tom Thomson did. A playwright, Strube has an ear for dialogue, and the novel is enlivened by conversation by the people all around Harriet, from confused senior citizens to forthright angry teens, and we see all the information contained within these throwaway lines being filtered through Harriet’s precocious but still eleven-year-old brain and how they come to inform her view of the world. The connections she makes between her father’s obsession with cycling and her stepmother’s IVF cycle, for example, or how a diatribe from the malicious Gennady becomes the title of a sculpture she creates called “The Leopard Who Changed Her Spots.” In a subtle fashion, this is very much a novel that is preoccupied with language, by words, and the puzzles of what things really mean.

As in her previous work, Strube is unafraid to portray adults as a ragtag collection of lost souls and idiots. (This is another feature this novel shares with the collected works of Louise Fitzhugh.) That such folks are responsible for the care of vulnerable people is always a terrifying thing for those people to discover, and On the Shores of Darkness… is about that loss of innocence, the realization that none of us are really ever safe, and that our parents are as vulnerable as we are. “I want you to get better, but I don’t want to be blamed,” admits Harriet’s mother at one point regarding her son’s unhappiness, which is indicative of every adult’s failure in this book to take responsibility for his or her own actions, for their own life. “All of this has been very hard on me,” so say the grown-ups in relation to their children’s hardships, over and over again.

At nearly 400 pages, the novel is long, but swiftly paced and never dull. The bleakness of its considerations are broken up with incredible humour, from the cacophony of the voices in its background to the sheer audacity of Harriet herself, her nerve, all the things she is willing to do and say. There is a humour too in the contrast between the child’s point of view and the world around her, and—in the case of Harriet’s friend, Darcy, in particular—the person she is trying to to be. The sheer naïveté of these would-be old souls. Darcy likes to go on about, “that Caitlin whore,” a friend from her old neighbourhood, and we learn about what Caitlin did to her at Guides: “I was a Sprite and she was a Pixie. That ho bag made like all the cool girls were Pixies….Then the skank fucked up my puppetry badge.”

There is a twist two thirds of the way into the novel that is absolutely devastating and potentially crazy-making, but Strube manages to make the final section work with the introduction of a new character, a young girl who underlines the novel’s Fitzhugh ties by her determination to be a detective, carrying a magnifying glass and clues jotted in a notebook even. And while the novel veers dangerously toward sentimentality as it heads to its conclusion, Strube shows just enough restraint, and manages an impeccable ending, one that brings its pieces together, steady as the beat of a heart.

April 18, 2016

How books talk to each other

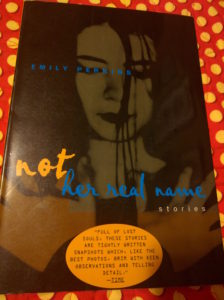

Tonight I was inspired by Sarah’s #ShortStoryaDay post to pick up “Not Her Real Name,” by Emily Perkins, from her short story collection of the same title. I’d first read the collection when I interviewed Emily Perkins in 2008, when Novel About My Wife came out. In her post, Sarah notes that she was surprised to reread this story and discover that two characters share a name with her daughter, and surmises that it was was with this story that she first fell for the name. She quotes a couple of lines from the story: “—Imagine a couple both called Thea, says Thea. —Isn’t it awful? One of the hazards of same-sex relationships I suppose.”

Tonight I was inspired by Sarah’s #ShortStoryaDay post to pick up “Not Her Real Name,” by Emily Perkins, from her short story collection of the same title. I’d first read the collection when I interviewed Emily Perkins in 2008, when Novel About My Wife came out. In her post, Sarah notes that she was surprised to reread this story and discover that two characters share a name with her daughter, and surmises that it was was with this story that she first fell for the name. She quotes a couple of lines from the story: “—Imagine a couple both called Thea, says Thea. —Isn’t it awful? One of the hazards of same-sex relationships I suppose.”

Now right now I’m reading a book called The Name Therapist, by Duana Taha, which is so much fun and absolutely fascinating and I can’t wait to tell you all about it. And perhaps I should have seen it coming, going from such a non-fiction book about names and how they define their bearers to a story called “Not Her Real Name” that I might encounter uncanny connections. And while I didn’t encounter either of my own daughters in this story, what I did find was really kind of strange.

I read the beginning of the story, the part about the two Theas, and then went back to The Name Therapist, in which Taha writes about the possibilities of same-name couples in same-sex relationships and how this idea fascinates her as a name enthusiast. And then there was a bit about a guy named Marc who orders coffee at Starbucks and gives his name as “Marc with a C,” which comes back on his cup labelled, “Carc”. Going back to “Not Her Real Name” then to find another Marc drinking coffee:

“Marc with a c. Cody’s seen it written down by the telephone… Marc. Marc. There’s something disturbing about the name. Like Jon without an h. Or Shayne with a y. Marc. Spelt backwards, it makes cram. A real word. This makes it seem like code. Code for what? Cram, cram. Trying to break the Code. OK, so her own name is enough of a liability. She shouldn’t laugh at other people’s. But Marc—its like biting tinfoil.”

Cody’s own name is referred to in connection the Jack Kerouac novel, Visions of Cody, which she’s never read, she says, and I haven’t read it either. I’m still a bit confused by the story’s title and what it means exactly, trying to break that code. And maybe this is the point. Earlier in the story, Cody’s thinking about a guy called Francis. “You always thought, Francis, rhymes with answers. Which it doesn’t, really. But you’d change the s of answers to be soft like his name.”

And isn’t all that so weird? I am really not so singular but I suspect that I am the only person in the world who is reading The Name Therapist and “Not Her Real Name” concurrently, two works that speak to each other so clearly, asking questions with answers echoing back. A book that came out the other day with a short story collection that was published twenty years ago by an author on the other side of the world—and they are connected in ways their authors never even fathomed. And this is why I love books and literature so much, that it’s all a code, quite beyond us and quite unbreakable. And the infinite possibilities of these connections too, how books upon books can talk to each other, the libraries of the world abuzz with these private conversations.

April 18, 2016

In Praise of Messy Blogging

I have started unfollowing all the people on Instagram whose corporeal selves are represented sole by a pair of legs. Not necessarily because it’s repetitive, because certainly they change up their knee socks and stripy tights, but because it’s just weird. How are we to know that these people are not (part of) an octopus? How much do you ever know a person when you know her only from the mid-thigh down? And what are these disembodied limbs (that are not entirely distinct from the kind you’d find at a crime scene, albeit a carefully arranged, colour-coded crime scene with impeccable lighting) telling us about the way that people are decided to construct their selves online?

I have started unfollowing all the people on Instagram whose corporeal selves are represented sole by a pair of legs. Not necessarily because it’s repetitive, because certainly they change up their knee socks and stripy tights, but because it’s just weird. How are we to know that these people are not (part of) an octopus? How much do you ever know a person when you know her only from the mid-thigh down? And what are these disembodied limbs (that are not entirely distinct from the kind you’d find at a crime scene, albeit a carefully arranged, colour-coded crime scene with impeccable lighting) telling us about the way that people are decided to construct their selves online?

I’ve been thinking about writing this blog post since reading Melanie’s Instagram post on social-media burnout a few weeks ago. She’d been contacted by someone wondering why she didn’t separate her bookish Instagram posts from ones related to her personal life, her family and her health, and become “a real bookstagrammer.” It’s advice I find so baffling as someone who’s been sharing my life online for nearly sixteen years, as well as reading about other people’s lives. Because for me, these windows into other people’s worlds has always been the most remarkable thing about web 2.0 and beyond it. In the very best book blogs, it’s not necessarily the reviews themselves that are so compelling, but what they tell us about the person who is writing them, and how the books fit into the larger narrative of the writer’s life. And I end up having a better understanding of where the writer is coming from and how their reviews work because I’ve read the posts in between (and between their lines even) and have a sense of who these people really are.

Partly this is a question of medium, of course, of platform. Superficially, old school blogs and Instagram are different, though I would argue that the latter is definitely informed by the former. And because there is no character limit on captions, Instagram has the same potential for in-depth posts which is followed up by the kind of community engagement we haven’t really seen on blogs for about a decade. But there is not the same sense of ownership of an Instagram account that one has of a blog, a “homepage,” and more of a tendency toward conformity and memes. With the immediacy of Instagram, it’s simplest to learn how it’s done by watching others. The community connections resulting from hashtags and memes are as such that Instagrammers are less inclined to operate beyond the lines of wider experience. Blogging was about being on the margins; Instagram is about being central. And of course, the platform is image-driven, and so how things look will always take priority over how things really are.

Partly this is a question of medium, of course, of platform. Superficially, old school blogs and Instagram are different, though I would argue that the latter is definitely informed by the former. And because there is no character limit on captions, Instagram has the same potential for in-depth posts which is followed up by the kind of community engagement we haven’t really seen on blogs for about a decade. But there is not the same sense of ownership of an Instagram account that one has of a blog, a “homepage,” and more of a tendency toward conformity and memes. With the immediacy of Instagram, it’s simplest to learn how it’s done by watching others. The community connections resulting from hashtags and memes are as such that Instagrammers are less inclined to operate beyond the lines of wider experience. Blogging was about being on the margins; Instagram is about being central. And of course, the platform is image-driven, and so how things look will always take priority over how things really are.

For me, a blog has always been a little bit like a selfie. (I don’t mean this in a bad way. Selfies are wonderful. Nothing tells a story like the human face, though it’s true that a little less duckface would go a long way.) This was the case even back when I started blogging, when platforms didn’t support images and no one’s phone even had a camera. The appeal of the blog has always been its human face, even with blogs as divergent as those lists of links that were essentially internet filters or those that functioned as online diaries. Whatever the material and how it was presented, a blog gave the reader a sense of the human being that was behind it. (Now whether that human being was an accurate representation of its writer is another story; I also love May Friedman’s suggestion that a person being about to construct their own online identity is not particularly a bad thing.)

Sometimes I get the sense that Instagram is about obscuring the humanness though. Pip Lincolne has written a terrific post about virtuous intentions and true character—that one is about becoming while the other is about simply being. She posits that true character is less easily displayed through visuals and more likely to be found on Twitter or long-form blogs, while Instagram is the ideal platform for these people striving to be their best selves. Which can be kind of crazy-making. Which can have the effect of reducing a person to a pair of limbs, because everything else is too complicated.

Sometimes I get the sense that Instagram is about obscuring the humanness though. Pip Lincolne has written a terrific post about virtuous intentions and true character—that one is about becoming while the other is about simply being. She posits that true character is less easily displayed through visuals and more likely to be found on Twitter or long-form blogs, while Instagram is the ideal platform for these people striving to be their best selves. Which can be kind of crazy-making. Which can have the effect of reducing a person to a pair of limbs, because everything else is too complicated.

(I love Instagram. Have I made that clear? It enriches my life exponentially, and has connected me with amazing people, and inspires me immensely. It highlights that beauty is everywhere, even in the most curious corners. I also find it fascinating that Instagram, like blogging, is impossible to generalize about. For every pair of legs, there is a girl tight pants doing complex yoga poses on the beach or posing in the bathroom mirror showing off her fantastic outfit. I love the radicalness of Instagram accounts that give fat women or non-binary people the chance to construct their identities and be seen. And if the human face is what I’m looking for, there are many Instagram accounts that feature nothing but…though these accounts come with their own questions and complications.)

Blogging is about process. This is what I tell my students, and for many of them their biggest challenges involve overcoming notions of perfectionism and letting their unpolished selves show, using a blog post as a kind of working-though (which is what I am doing right now). But Instagram, and more visual-driven blogs, are about results. It’s about polished veneers and flawless skin tones. There’s less room for nuance, for delving into the realities of being, warts and all. Instead, there’s just a photo of a wart. And who would ever want to look at that? And now it seems I’m getting confusing because if blogging is about process, then isn’t that the “becoming” that I connected with Instagram two paragraphs back? What’s the difference between becoming and process? But I think the distinction is that with blogging, process itself is a way of being. It’s accepting life itself as a work-in-progress, and the destination is never ever the point. (Arriving at your destination, of course, would only mean that you’ve finished blogging; it would only mean that you’re dead.)

Blogging is about process. This is what I tell my students, and for many of them their biggest challenges involve overcoming notions of perfectionism and letting their unpolished selves show, using a blog post as a kind of working-though (which is what I am doing right now). But Instagram, and more visual-driven blogs, are about results. It’s about polished veneers and flawless skin tones. There’s less room for nuance, for delving into the realities of being, warts and all. Instead, there’s just a photo of a wart. And who would ever want to look at that? And now it seems I’m getting confusing because if blogging is about process, then isn’t that the “becoming” that I connected with Instagram two paragraphs back? What’s the difference between becoming and process? But I think the distinction is that with blogging, process itself is a way of being. It’s accepting life itself as a work-in-progress, and the destination is never ever the point. (Arriving at your destination, of course, would only mean that you’ve finished blogging; it would only mean that you’re dead.)

In blogging, process means showing your work and necessitates a bit of a mess. You’ve got to be a bit vulnerable, which goes against all the general advice these days about building a brand online. But the reasons for not positioning oneself as an online guru are tenfold, least among them that you’re totally lying (and if you weren’t, you’d probably have a platform that wasn’t a blog), although ultimately it’s just not sustainable. As I explain in my blogging course, if you’re writing only about those things on which you’re an expert, you’re probably limiting yourself, whereas if you’re willing to explore all you don’t know, the possibilities are infinite. It also means that if you’re making your online project an act of discovery, you’re getting something out of it beyond the (likely) pennies of ad revenue coming your way. Anyone who has ever read a novel too knows that discovery is so much more interesting to read about than somebody who knows everything already.

I also think that the pressure to know everything and be everything all the time is a lot to put on a human being, one who is doing unpaid work at that. And that allowing that human to be human is healthy and therapeutic. When a person is feeling lost and alone, there is nothing more heartening than learning there is somebody else out there who’s been there, who understands…the amazing miracle of human connection that has always been the best part of blogs anyway.

Letting humans be human then means that a person is not simply a pair of legs, or only a bookstagrammer. But rather that a person is a bookstragrammer with an actual life of which bookstagramming is simply a facet, and there are also friends and family, an interest in wildflowers and bundt cake, messy bedside bookstacks, children with dirty faces, an obsession with The Bachelor and Little House on the Prairie fan fiction—do you know what I am saying? Also, when you’re scrolling through photo after photo of impeccably arranged books on tea trays with sprigs from the garden and an artful jug against a painted wooden floor, don’t your eyes kind of glaze over?

Letting humans be human then means that a person is not simply a pair of legs, or only a bookstagrammer. But rather that a person is a bookstragrammer with an actual life of which bookstagramming is simply a facet, and there are also friends and family, an interest in wildflowers and bundt cake, messy bedside bookstacks, children with dirty faces, an obsession with The Bachelor and Little House on the Prairie fan fiction—do you know what I am saying? Also, when you’re scrolling through photo after photo of impeccably arranged books on tea trays with sprigs from the garden and an artful jug against a painted wooden floor, don’t your eyes kind of glaze over?

Hybridization is the best thing that blogs have on their side—in terms of form and technology. And I am convinced the same can be true of content, no matter who’s out there persuading others to becoming “real bookstagrammers”. And who, by the way, are the people doing that kind of persuading? I do suspect their marketers looking for the peddling of their own wares, and it’s far more simpler and salubrious to have your products marketed (without pay, no less) by people who have no human foibles and are wart-free. It also makes me sad that there are people living who’ve never known a time in which the central experiences of being online were not selling stuff and being sold stuff. In the words of Bonnie Stewart, “forget agency and voices and relationships. if you are using your network solely to sell the message of a corporate entity, what you are doing is NOT social media, no matter your platform. what you’re doing is at best a marketing job, and more likely something akin to Amway.”

I am hopeful though. I’ve been noticing a trend among Instagrammers to show their faces once in a while, with various hashtags attached to this, latching onto some kind of meme, and positing the whole thing like some kind of revelation. With these big reveals too have come some genuinely fascinating insights: one woman explained that she’s been dealing with a debilitating skin ailment for the past while and she’s been terrified to show what she really looks like. Another reviewed the new book, 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, and wrote about being fat, something she’d never dealt with in her blog before and which never been clear in her carefully positioned photos. And I can’t help but think how liberating it must have felt to finally admit these things, to own one’s imperfections, to put these things out there for everyone to see and discover that the world still likes you anyway. And for readers I am sure these posts were most remarkable too; certainly here I am still thinking about them weeks later.

April 17, 2016

The M Word: Dear Me, by Nicole Dixon

This is the third in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From previous weeks: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“; “Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self”

In her essay in The M Word, Nicole Dixon ruminated on her choice to be child-free, considering the parts of the choice she was uncertain about and and those she knew for sure, one of which was that saying no to kids is not the same as saying no to life, to love. And in this follow-up piece, she finally steps into the sun.

*****

Dear Me,

Dear me! I have to warn you—you’re about to go through two years of hell, but you will get through those two years and on the other side, the side I’m on now, you will be stronger, more hopeful, more at peace than you’ve ever felt. Trust me.

Take solace in your garden, in books, in silence and stillness, in the life you’ve built for yourself in this worn-out town on this beautiful island. You can do it. You’ll get through this. Go for walks. Stare at the ocean. Breathe it in. Feel how big it is, how easily it swallows your sorrow and carries it away on its tides and currents.

Your M Word essay, rereading it, is about choices, and you are about to make plenty. You will quit your shitty job after fighting an abusive boss; you will choose to change the system until you realize how broken it is. You will then choose to turn your back on that system in order to build a new one. You won’t know how to do this or where to begin until one day you will stand in your garden and you will hear it: here. Start where you are. Grow where you are planted. Here—this backyard, this soil, this town, this island. Stay put. Stop moving. Root yourself here. The answer, a dormant plant, will suddenly bloom like spring.

But your hardest choice will be your decision to stop talking to your mom. You will turn to her for support during all your work shit, and she will once again rage at your choices and, finally, after years of fearing your mother, you will choose to step out from her shadow and feel the sun. You too, like your garden after winter, will thrive in the warmth of that sun.

And you will realize, in this choice more than so many others, how much your mother’s abuse has influenced your decision not to have kids. You can’t write about it now, can’t even admit it, but you will. And the darkness she inherited from her mother, the darkness she tried to pass on to you, is a trait you need to nip in the bud. Instead, you will make and nurture another life, other lives, your life. You will grow food in your soil, in a town that has weathered its share of abuses, and you will write about this, you will write and love the land, the earth, and it, unlike your mother, will love you.

Go to your garden. Feel and grow life there. Let it fill you. It will. Believe me, it will.

Be strong in your choices and enjoy the sunlight,

Me

***

Nicole Dixon’s first book was the collection of stories, High-Water Mark. She lives in New Waterford, on Cape Breton Island.

April 15, 2016

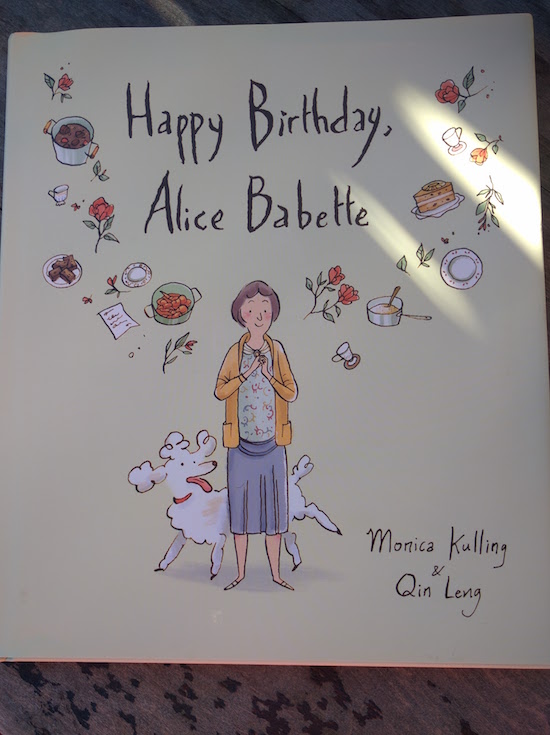

Happy Birthday, Alice Babette, by Monica Kulling and Qin Leng

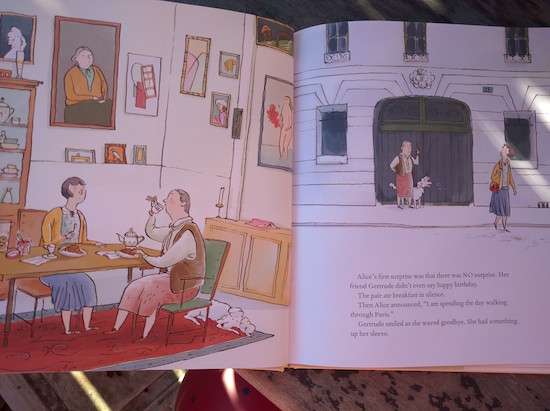

If you loved Julia, Child, by Kyo Maclear and Julie Morstad (and who didn’t?) then you must feast your eyes on Happy Birthday, Alice Babette, by Monica Kulling and Qin Leng. Here is another autobiographical picture book about an admirable American in Paris, as Kulling tells the story of the relationship between Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. Monica Kulling’s picture books always come with a sweet subversive bent, and this one is no exception. Because it’s huge to see a lesbian couple depicted in a picture book, to see a female character who looks like a man and can’t be arsed in the kitchen (and when she is, it all goes wrong because she forgets to check the oven because she’s consumed by the composition of a poem), to see this example of a family (two women, no kids) because this is what Gertrude and Alice are, how they care for one another, each complementing the other’s strengths (though it’s true that Alice seems to have the patience of a saint).

Although young readers will only pick up on all this subliminally. The children who pick up this book will be delighted by Qin Leng’s whimsical stylings (which we know from works like A Flock of Shoes) and this story of a woman named Gertrude and her friend Alice, whose birthday Gertrude becomes determined to mark in an extra-special way.

Although Gertrude says nothing of this in the morning as they eat their breakfast together, Alice announcing she’s going to spend the day walking around Paris, Gertrude with her own tricks up her sleeve.

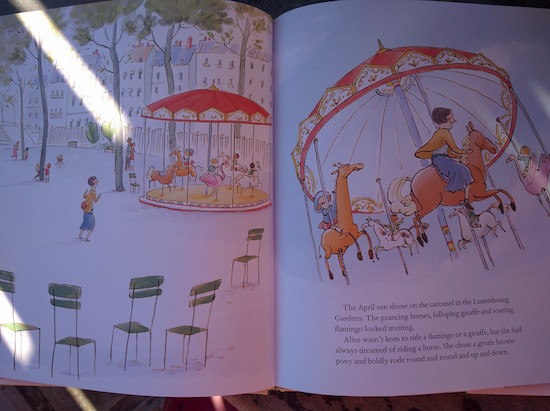

Alice has an eventful day just walking about, riding a carousel, watching a puppet show, and even diverting a would-be jewel thief as he attempts his getaway.

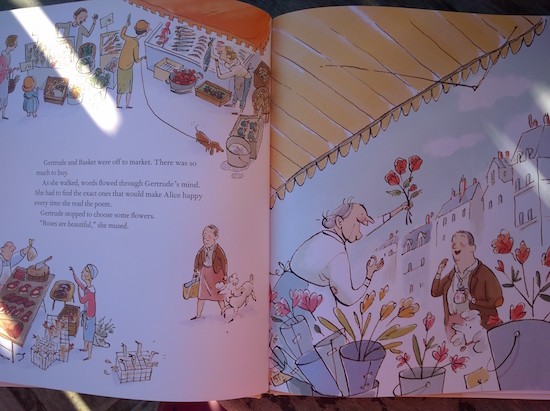

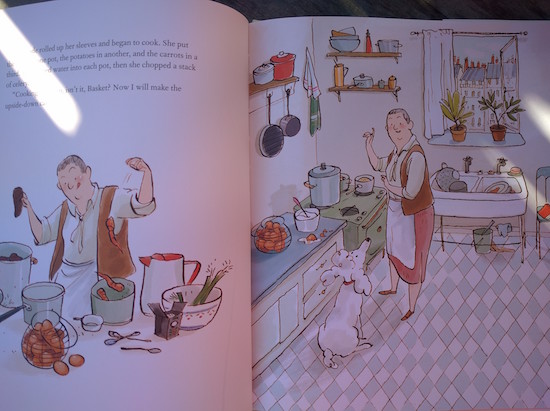

While Gertrude tries to execute her plan of making Alice a special dinner, and writing her a birthday poem. The latter’s inspiration comes easily enough as Gertrude buys a bouquet of roses from a flower seller and the ideas start flowing. Dinner, however, proves to be more of a challenge.

Gertrude does her best, even attempting to top it all off with a pineapple upside-down cake, but composing the poem turns out to be quite the distraction. So much so that she leaves the kitchen unattended, everything burnt to a crisp, Alice discovers, as she returns home from her “day of marvels.” And by this point Gertrude is lost altogether, busy at her desk turning her cooking misadventure into a story. Fortunately when their friends arrive for the party, they’ve got some food in tow and so Alice’s birthday can be properly celebrated after all—and Alice has made brownies for dessert (though it’s not clear whether these are her special ones).

It’s not a fair story, with poor Alice being left to clean up Gertrude’s mess, but then so often love really isn’t. Instead, this is a truer story about love and togetherness, and the myriad ways that two people can build a life together.

April 13, 2016

The Road to Atlantis, by Leo Brent Robillard

Leo Brent Robillard’s novel The Road to Atlantis has been sitting on my shelf for about six months, and while I’ve wanted to read it—it’s a novel about family, and I love that cover—I’ve been terrified to pick it up. Because it’s a novel that begins with the death of a child, and I just don’t want to go there, not even in fiction, and also because a novel about the death of a child is so easy to do badly, all emotional manipulation and cliche. But last week I’d finally steeled myself, and I am so glad I did. The Road to Atlantis works on every level.

Leo Brent Robillard’s novel The Road to Atlantis has been sitting on my shelf for about six months, and while I’ve wanted to read it—it’s a novel about family, and I love that cover—I’ve been terrified to pick it up. Because it’s a novel that begins with the death of a child, and I just don’t want to go there, not even in fiction, and also because a novel about the death of a child is so easy to do badly, all emotional manipulation and cliche. But last week I’d finally steeled myself, and I am so glad I did. The Road to Atlantis works on every level.

Here’s why. The tragedy occurs in the first chapter, and we know it’s coming. Anne and David are at the seashore with their two children on a summer vacation, and while the plot is taking the reader toward the inevitable moment (because the back of the novel has told us as much) the narrative itself is concerned with all the details and frictions of ordinary life, which is to say that there aren’t any ominous clouds, or if they are, we only notice them in retrospect. And when it finally happens—their daughter disappears while swimming, and the entire beach goes on alert as they search for her, because perhaps she’d only wandered off —David thinks, “So this is how my life was meant to be…This is what tragedy feels like.” But we don’t hang there for long inside that moment. Within a paragraph (“This is it, he thought.”) this chapter is over.

We’re given a blank page for the purpose of recovering our senses (for certainly, the end of the first chapter hit me like a gut-punch) and when the second chapter begins, we find the family a year ahead in time, their lives seemingly resumed, the rest of the world no longer so conscious of the tragedy that had befallen the Henry family. Which makes it almost easier to carry on the charade that life goes on, these characters still stunned, numb and vacant as it does. And it’s here where the novel launches, taking us through the next two decades of their lives, the moments where Anne and David hang together and where they fall apart, each of them navigating grief in their own way. And it is in their own way, ways that are so connected to the people they were before their daughter died (the people we met in the first chapter) that these trajectories seem inevitable. “This was how my life was meant to be.” This entire novel is about that resignation.

Which sounds depressing, but there’s too much substance to be simply that. At one point in the novel, David takes his high school history students on a field trip to the Diefenbunker near Ottawa, a Cold War era bunker deep under ground, and while the narrative too plumbs similar depths, it’s not the plunge itself that matters but the scenery down there. We see David and Anne trying to carry on with ordinary family life, performing their respective jobs well and less well, parenting their son as he grows older, confronting their own family histories, and yes, all the while their daughter is present, memories of her stirred continually. They’re pursuing their own passions and fascinations, some of them inexplicable. Turns out “This was how my life was meant to be,” is not as straightforward as one might assume, because while the tragedy of a child dying touches everything, there comes a point at which it no longer defines it.

I loved this book, it’s depiction of real people who are so thoroughly tied to the world, although there are certainly moments at which they might not want to be. The Road to Atlantis is an engrossing read, the reader swept along by its pace, and as amazed at what time can do as its characters are.

April 12, 2016

April 30: Authors for Indies

I still remember what it felt like to take for granted the bookstore that was located within a five minute walk from my house. To have it suddenly occur to me mid-morning that I was yearning for a copy of, say, The Mystery of the Shopping Cart, by Anita Lahey, and then to just venture out and get it. To ask the clerk at the counter if they had a copy—because it’s a collection of essays, poetry, and criticism, and I couldn’t imagine where such a book could be found in the shop, and because it’s a small press title, the slim kind that can get lost easily amongst bigger books—to be told that they had two. And then there it was: the book I wanted in my hands. Could there be a more efficient system?

The lovely people of Blue Heron Books in Uxbridge.

I was spoiled. I was. Because even now, two years after Book City closed their Annex location and left Bloor Street bookless, I am feeling the loss, even with the excellent bookstores still in our midst: I frequent Bakka Phoenix Books and Parentbooks on Harbord Street, and Little Island Comics on Bathurst is a kidlit oasis, and while I am so glad that these speciality stores have found their niche and continue to survive, I miss the generalness of Book City.

I miss a bookstore that specialized in everything: new releases, award-winners, mid-list titles, thrillers, memoirs, CanLit, non-fiction, and small press gems. I miss the discovering of walking around Book City’s shelves and tables: I still remember the excitement of discovering a new Margaret Drabble release I hadn’t heard of; and I remember going in to pick up Zadie Smith’s NW on its release date in 2012; or the day I bought The Goldfinch. I remember years ago when I didn’t have money to buy books as prolifically as I now do, and what it meant to hold these books, to want them and wait for them. I remember when my husband was unemployed and I didn’t buy new books for ages, and then he got a new job, and Book City purchases were the first ones I made and it felt so good—so you see, I wasn’t always taking it for granted. I always knew how lucky I was. Maybe what I mean by taking it for granted instead is that it was just so imaginable that it could possibly end.

I miss a bookstore that specialized in everything: new releases, award-winners, mid-list titles, thrillers, memoirs, CanLit, non-fiction, and small press gems. I miss the discovering of walking around Book City’s shelves and tables: I still remember the excitement of discovering a new Margaret Drabble release I hadn’t heard of; and I remember going in to pick up Zadie Smith’s NW on its release date in 2012; or the day I bought The Goldfinch. I remember years ago when I didn’t have money to buy books as prolifically as I now do, and what it meant to hold these books, to want them and wait for them. I remember when my husband was unemployed and I didn’t buy new books for ages, and then he got a new job, and Book City purchases were the first ones I made and it felt so good—so you see, I wasn’t always taking it for granted. I always knew how lucky I was. Maybe what I mean by taking it for granted instead is that it was just so imaginable that it could possibly end.

A bookshop on a boat—why not?

If there is a bright side to the closure of my local, however, it’s that it’s inspired me to take up Bookshops as destination travel. With a store like Book City no longer at arm’s reach, it’s up to me to seek them out, and so we do: a trip to the East or West end now inevitably brings a stop at the Book City locations in those areas; we make day trips to places like Blue Heron Books in Uxbridge (which was definitely worth the journey, and we’re going to do it again this summer); and a year ago we spent two weeks in England visiting one amazing bookshop after another. Because there is no better way to travel.

Last year at Authors for Indies

And now I’m exciting to be making another bookshop my destination, although I’m not the only one. On April 30, I’ll be taking part in the second annual Authors for Indies Day and pushing titles at Book City on the Danforth (348 Danforth Avenue) between 4 and 5pm. I did this last year and it was ridiculous fun, to meet other readers and connect them with books they’re totally going to love, and just to be in a bookshop (which really is my natural environment). So I hope you’ll come and browse with me, and we can talk books, and love books, and buy them too, supporting these shops that mean so much to our communities and without whom our streetscapes would be so much bleaker.

See you there?

And find out what Authors for Indies events are happening in your neighbourhood.