May 6, 2016

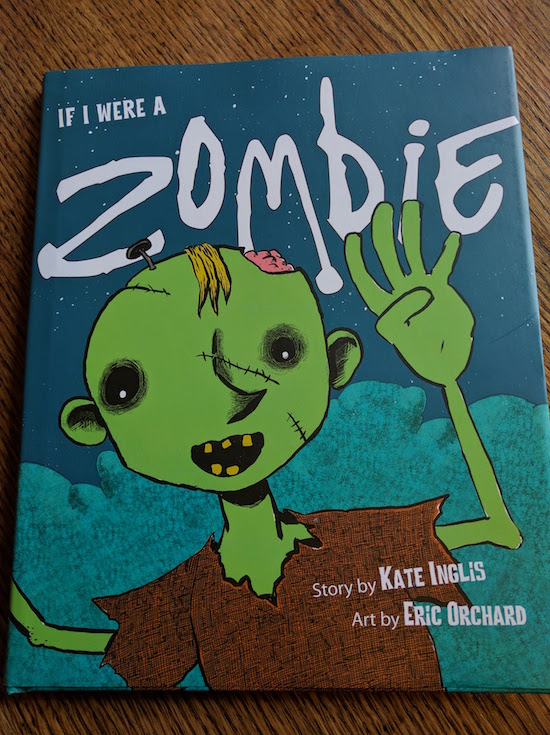

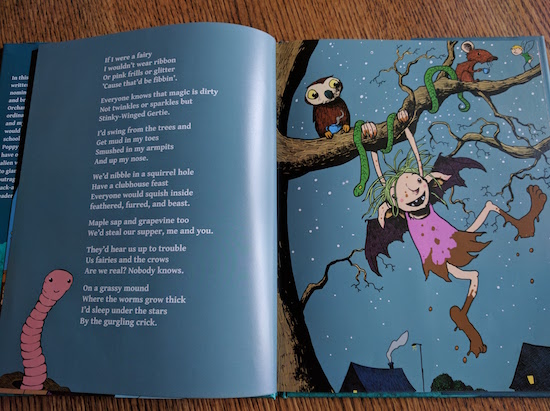

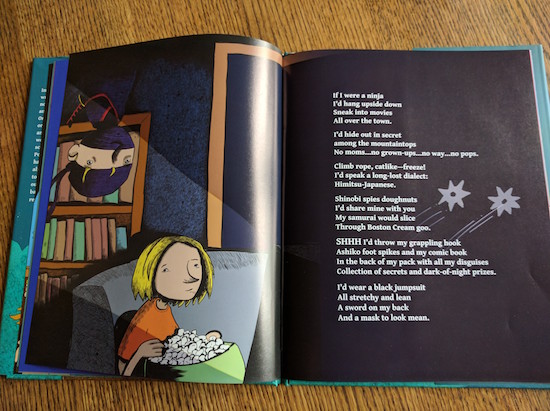

If I Were a Zombie, by Kate Inglis and Eric Orchard

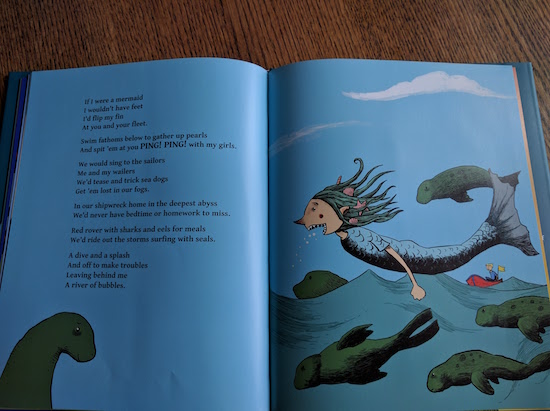

True confession: I don’t really get zombies. Along with “Talk Like a Pirate Day” and Nutella, zombies are a wildly popular phenomena whose appeal I just don’t understand. (I also have no strong feelings about Prince or Shakespeare, which made last week kind of strange.) What I do like is a beautiful picture book though, a kid-friendly one that my children delight in as much as I do, and so to that end, the undead notwithstanding, Kate Inglis’ latest book, If I Were A Zombie, illustrated by Eric Orchard, totally delivers.

The premise is this: the narrator explores the various possibilities for selfhood amidst the kinds of creatures with children tend to be most fascinated: fairies, giants, witches, pirates and vampires. And even actual ninjas! Plus the zombies, of course.

The text is poetry, whose structure reminds me of Sleeping Dragons All Around, by Sheree Fitch (which is by the same publisher). Admittedly, rhyming couplets would have made for an easier read—sometimes the prose is tricky to say, and it’s hard to keep a rhythm—but I am not sure that such bounciness was ever Inglis’s intention. This is also a book that older children will read on their own which makes matters of rhythm irrelevant. And read it, they will. This is a book with zombies and ninjas after all. But there is more to it than that—this is a book about exploring all kinds of being, about possibilities, and adventure, and dreaming up stories for our lives. Teachers and other grown-ups will easily be able to encourage young readers to explore all kinds of “If I were….”s of their own, after trying out the various roles suggested in the book.

My very favourite thing about If I Were a Zombie though is its treatment of gender, assuming boys and girls alike as its readership—and also that all possibilities in the story are open to both of them as well. For a boy to have fairies and mermaids in his story—and I love Orchard’s non-cutesy takes on these. For children to read a book in which the superhero is a girl, which is particularly appealing to my superhero-loving daughter too. I love how gender becomes completely irrelevant, and all possibilities are open to either.

PS: If I Were a Zombie makes a very cool companion to Vikki VanSickle’s If I Had a Gryphon, but concerned with monsters and imagined creatures, as well as the conditional tense.

May 5, 2016

The M Word: Ariel Gordon’s Additional Dependent

This is the sixth in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From previous weeks: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“; “Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self”; “Dear Me, by Nicole Dixon“; “Kerry Clare on Motherhood and Abortion” ; and “Christa Couture: Ever Since the End.”

“Primipara,” Ariel Gordon’s essay from The M Word about her choice to have one child, was one of the most widely remarked upon in the book’s critical responses—not least for its inclusion of her poem of the same name which began, “If I had had twins, I would have eaten one.” It was Gordon’s essay that earned The M Word its unlikely place on Brain Child Magazine’s Humour Book List last year. And now she catches us up to the very surprising news that her family has since acquired a new addition.

*****

My partner and I were together for seven years before we got knocked up.

It took us another decade to acquire an additional dependent.

In those ten years—the age of many of my friend’s marriages before they busted up—we had a tank full of fish which included Downie, a black Asian Upside-down Catfish.

We hand-fed Downie shrimp pellets, until those weren’t enough and s/he started eating everyone else. (One fish leapt to his/her death to avoid Downie’s jaws-of-death. S/he became fish-jerky between the dresser where the tank sat and the wall: “It smells in my room,” my daughter noted.)

We surrendered Downie to the pet store. We didn’t mention s/he was a cannibal.

Next we got black-and-white Mollies, which are starter fishes like Tetras, the difference being that they are prolific breeders. One female came pre-loaded with enough sperm that she gave birth every month for six months. She was the alpha: she got huge and monstrous and wouldn’t let any of the other Mollies eat, nipping their fins and head-butting them. And then she’d release a brood of baby Mollies, which looked like flecks of ash. They’d hide in the aquatic plants we grew in the tank, which came from the store infested with snails.

We surrendered entire litters of small black Mollies to the pet store.

After we drained the fish tank, my daughter pined, though she’d shown very little interest in the fish.

“I want a real pet,” she said. “Can we get a real pet?”

The summer after we drained the tank, we found a greeny-yellowy wild salamander swimming in the pool with us at the water park in Portage La Prairie. That fall, someone brought a carsick hedgehog to daycare. (“It pooped on two of my friends,” my daughter reported, excited.)

So we had serious conversations about salamanders, lizards, and geckos and then hedgehogs, guinea pigs, and rats. Anna pushed for a cat or a dog, though what she really wanted was a perpetual kitten or puppy. I resisted, citing my furry-animal allergies, but was glad that the conversation was about having-a-pet and not about having-a-sister/brother.

Now, I don’t watch kitten videos or hunt baby animals on the Internet. But when summer rolled around again and a friend posted pictures of a small white kitten stretched out, yawning, I felt a pang.

A friend of hers was trying to find homes for three kittens, including the white one. It turned out that I knew the friend-of-a-friend, so one Sunday, we went to go see them. The girl could barely contain herself on the way there, but neither of us connected with the kitten, so next we visited a no-kill shelter. I sneezed, my nose dripped, but we were both suddenly determined.

A week or so later, we brought home a half-grown black-and-white cat.

We only wanted one child and we similarly only wanted one cat. Not two or three, or a cat and a dog. One cat. But, unlike my daughter, we’ve so far managed to keep the cat out of our bed.

My boss and I commute to work together. When I told him we’d gotten a cat, he had one question.

“Who’s home the most?”

“I am,” I answered.

“She’ll love you best, then,” he said. He said with pets it’s a combination of who spends the most time with them and who feeds them.

This logic could equally be applied to children, of course. Mothers are still most often the ones home with their children when they are babies, primarily because they gave birth to them and have the boobs with which to feed them with. But I’m sure half the reason that mothers often have such strong bonds with their children is because they spend all those endless early days and weeks and months with them, skin on skin.

My boss was right. Given a choice, Kitty prefers to sit on my boobs, wedge her knobby spine under my chin, and listen to my heartbeat. She bunts my glasses aside, spreading contentment pheromone all over the bones of my face. If she’s feeling particularly tender, she licks my eyelids.

According to the Internet, this is submissive behaviour. She’d do the same to the alpha if she lived in a community of cats. She also rolls on the ground the moment the front door opens, showing her belly, as if to say “Hello, big hairless cats! Please love/feed me…”

Nowadays, people refer to their pets as furbabies and to themselves as their pets’ parents. But I prefer to think of myself as a cat that is slightly higher than Kitty in the social hierarchy. I have certain responsibilities to her—and affection for her— but I am not her parent.

Last night, after the girl had gone to bed, I was sitting on the couch and Kitty assumed her usual position. Except this time, she reached out and softly put her black-and-white paw on my eyelid. After a few moments, she tucked both paws under her body and promptly fell asleep.

When I was breastfeeding my daughter, I was often aware that I was putting my nipple into a mouth full of irrational teeth, that I was trusting her not to bite me.

Kitty’s paw is full of sickle-shaped claws. Her mouth is full of needles. But I am still willing to offer her my softest bits.

I’m good with animals, even if I don’t need them, if that makes any sense. When I was a kid, delivering newspapers in my neighbourhood, I came to an understanding with each of the neighbourhood dogs. They stopped barking at me when I entered their territory; some of them even offered me their bellies to rub.

Once, I was walking down my street at night and saw a dog-shaped animal twenty feet away. When I got a bit closer, I saw that it was a red fox. But I still bent down and offered my hand and said soft things, trying to tempt it to closer. We looked at each other for long moments, but it was wild and eventually loped away. I hold that memory close, the same way I hold the memory of watching my late uncle dandle my youngest cousin when she was two weeks old, the way I hold the memory of that hot summer when my daughter was born, how naked we both were.

My daughter had hoped that the cat would be hers, that it would love her best, but I tell her that Kitty loves all of us differently. I tell her she has to be more patient with the cat, let it come to her, but she’s almost ten now and isn’t very patient.

What’s more, she’s starting to push me, alternating pouting with correcting every single thing I say. I am embarrassing, she says.

I tell her I could be much more embarrassing, given half a chance. She squints at me.

Today, between karate and groceries, the girl was hungry, so we stopped at Tim Horton’s for a bagel and cream cheese. And she pouted because I wouldn’t get her a Frozen Lemonade or a Maple Cinnamon French Toast bagel, restricting her to the tap water I’d brought from home and a Twelve Grain bagel.

We’d made it through the drive-through and were sitting at the light and she was lifting my water bottle to her mouth when the light changed. I moved smoothly into the intersection and had just completed my left turn when she yelped.

“What?” I said.

“Waaaaaah,” she replied.

“Anna, what?”

“You—jerked—the car…”

“Anna, I was driving. I didn’t jerk the car.”

“You made me spill the water all over myself…”

A sniffly moment of silence.

“Here, blot yourself.” I passed her the box of tissues I keep in the front seat.

“I don’t even know what that means.”

“It means pat yourself with the tissues.”

“Like that’ll make a difference…”

“Anna—“

“What!?!”

“I’m starting to get mad…”

We spent the rest of the trip to the grocery store in silence. After we’d found a parking space, I handed the girl a coin and asked her to go get a cart.

I’d opened the trunk and was preparing to transfer our bags and bins when Anna returned, parking the cart next to the car.

“Mama,” she says, her face pink from crying and bashful. “Can I have a hug?”

And I didn’t need the Internet to tell me that this was submissive behaviour. That she was trying to apologize for shouting at me and for pouting before that.

But the difference between Anna and Kitty and even the neighbourhood dogs of my childhood is that my relationship with my daughter is slippery; we are both alternately dominant and submissive. More than that, we are just people, trying to get along, even if I built her in my body, cell by cell, limb by limb.

“Yes,” I say. And I pull her close, holding her tighter than usual. I want her to remember that once neither of us could remember where she began and I ended. I want her to hear my heartbeat, thudding irrationally in my chest.

And I am suddenly glad we are here, damp and irritable, in this parking lot, that we have all made it this far. My daughter was born in the hospital; Kitty was born under somebody’s stairs. But we love each other, and we most of the time, we remember to pull our claws.

Ariel Gordon is a Winnipeg writer. Her second collection of poetry, Stowaways (Palimpsest Press), won the 2015 Lansdowne Prize for Poetry. She is currently working on CNF about Winnipeg’s urban forest, which is slated for publication in 2018.

May 5, 2016

CanLit Gets Name Therapy

Anne-with-an-E, Booky, Dustan, Daisy Stone Goodwill, Zenia, Aminata, and more…

Anne-with-an-E, Booky, Dustan, Daisy Stone Goodwill, Zenia, Aminata, and more…

Inspired by Duana Taha’s book, The Name Therapist, I’ve made a list of the most storied names in Canadian literature. I had the most ridiculous fun writing this post, and really could have written it forever and ever.

May 4, 2016

No big scheme

It’s interesting to me how social media has changed the way I blog. I use Twitter to share other people’s stories, whereas I used to collect these in link round-ups here, and Instagram to capture moments of domestic mundanity thereby rendering them a little less mundane (which is arguable, of course. And I still take care to keep it pretty mundane around here too). Instagram is also a good place to tell my own stories, but it takes me ages to type on my phone so I do less of this. An exception is the story of slut sign, which I shared last night, but it got a really nice response. Anyway, maybe it’s clearer to say that social media hasn’t changed the way I blog, it just has had me spreading my blogging wider, across platforms. Twitter, Instagram, Facebook—it’s blogging, all of it. (But what about Snapchat? I don’t know. A blogger can only spread herself so wide.)

It’s interesting to me how social media has changed the way I blog. I use Twitter to share other people’s stories, whereas I used to collect these in link round-ups here, and Instagram to capture moments of domestic mundanity thereby rendering them a little less mundane (which is arguable, of course. And I still take care to keep it pretty mundane around here too). Instagram is also a good place to tell my own stories, but it takes me ages to type on my phone so I do less of this. An exception is the story of slut sign, which I shared last night, but it got a really nice response. Anyway, maybe it’s clearer to say that social media hasn’t changed the way I blog, it just has had me spreading my blogging wider, across platforms. Twitter, Instagram, Facebook—it’s blogging, all of it. (But what about Snapchat? I don’t know. A blogger can only spread herself so wide.)

Which brings me to this article about the end of the blog, Bookslut, which was one of the first book blogs I read years ago when my blog wasn’t a book blog and I could only dream of such a thing, along with other bloggers like Lizzie Skurnick and Maud Newton. The interview is so candid, smart and pointed, and embodies so many of my own ideas about blogging and its inherent wildness (and messiness!) and the fact that blogs and making money were never ever compatible (and that if you’re making money with your blog, it’s probably ceased to be a blog) and that blogging in search of a book deal is a sad sad pursuit and an insult to the form.

Anyway, I already shared the article on Twitter, but I want to share it here too, along with some of my favourite bits:

- “Well, the only reason why Bookslut was interesting was because it didn’t make money, and when I realized the sacrifices I was going to have to make in order for it to make money, it wasn’t worth it.”

- ” There was no big idea, no big scheme. I just wanted to talk about books with my friends.”

- “There’s always space to do whatever you want. You won’t get as much attention, but fuck attention. Fight for integrity.”

May 4, 2016

Flannery, by Lisa Moore

There was little doubt in my mind that Lisa Moore could pull off a YA novel. I remember her teen character in Alligator, which was a book that just delighted me when I read it first, and the vividness of her point of view. And as a writer who so skillfully employs word as tools to create meaning, I was sure she had the deftness to tune her work to a different kind of reader. Which, of course, didn’t preclude me from reading it too. If she wrote One Direction fan fiction, I’d probably read that as well. Lisa Moore’s name is a literary hallmark.

There was little doubt in my mind that Lisa Moore could pull off a YA novel. I remember her teen character in Alligator, which was a book that just delighted me when I read it first, and the vividness of her point of view. And as a writer who so skillfully employs word as tools to create meaning, I was sure she had the deftness to tune her work to a different kind of reader. Which, of course, didn’t preclude me from reading it too. If she wrote One Direction fan fiction, I’d probably read that as well. Lisa Moore’s name is a literary hallmark.

So it’s no surprised that I really enjoyed Flannery, her latest book. The title character is a sixteen-year-old girl whose best friend has started ditching her for her cool musician (and slightly dangerous) boyfriend. Meanwhile, Flannery has got to complete an entrepreneurship project with her partner Tyrone, who she’s known since they were babies and is quite possibly in love with, but he’s not showing up to do any work, plus her free-spirited artist mother can’t afford to buy Flannery the new biology textbook she’s required to have, and keeps writing about Flannery on her parenting blog, which other kids at school are actually reading.

Flannery’s voice and point of view represents a stable force in a crazy world, and she’s an amazing mix of confusion, steadfastness and yearning. And naturally, I was very interested in her mother’s character, which Moore renders with just as much nuance. I think a lot about a mother’s right to tell her own story, even when her child is part of that story, because suggesting otherwise is another way of telling a woman to shut up. I do think that when a mother writes about her child with a great deal of thought, she can do this successfully, although Moore shows that Flannery’s mother Miranda is not too thoughtful about her blog (which disappointed me a bit—I would have loved some substance here), or anything, for that matter. Except her love for her children, of course, which is demonstrated in lovely, pointed ways—Miranda swooping in to exalt Flannery’s entrepreneurship project, her intuition regarding the well-being of her son, which her smartass daughter doesn’t give her credit for. Moore shows the the imperfect mother is the only kind of mother, and sometimes that all a child needs.

But of course none of this would be of much concern to the novel’s target readers, for whom Miranda would only be peripheral, I think. Those readers will be just as wrapt as I was by the story though, by Flannery’s incredible outlook on the world, but menacing shadows at its edges. And yes, there is edge here, real significant danger, and Moore so successful melds these points into a true, believable life, rather than using them for more sensational purposes (as bad YA novels might do, and even as a very good one like Raziel Reid’s When Everything Feels Like the Movies did quite deliberately). As the world’s is, the emotional spectrum of Flannery is wide. There is a scene in a mall food court where Flannery is betrayed by Tyrone that will break your heart as profoundly as that scene did in Moore’s February when her character waits in a bar for a date who never arrives.

Moore doesn’t push syntax and narrative structure quite as hard in Flannery as she does in her other books, which is the one significant way that the book is a break from her oeuvre. But here and there in her prose sparkles in just the same way her readers have come to expect: “The sun was so low that its reflection was a perfect bright red circle on the water’s surface and as the boat swing around, the circle was smashed into a thousand pieces that skittered away from each other and then floated back together, making the perfect circle again.” Such an extraordinary sentence! And what a gift to any reader, regardless of their age.

May 2, 2016

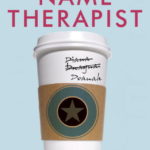

Tana French is Ruining My Life

I’ve been working my way through the works of Tana French ever since my friend Nathalie delivered all of her books to my house on New Years Day in a Waitrose bag, along with a container of soup. (Remember December, when everybody was sick?) Now usually such a loan would constitute a kind of imposition, but I’d been meaning to get into Tana French, and as soon as I opened the first book (In the Woods), I was hooked: “What I warn you to remember is that I am a detective. Our relationship with truth is fundamental but cracked, refracted confusingly like fragmented glass. It is the core of our careers, the endgame of every move we make, and we pursue it with strategies painstakingly constructed of lies and concealment and every variation on deception…”

I’ve been working my way through the works of Tana French ever since my friend Nathalie delivered all of her books to my house on New Years Day in a Waitrose bag, along with a container of soup. (Remember December, when everybody was sick?) Now usually such a loan would constitute a kind of imposition, but I’d been meaning to get into Tana French, and as soon as I opened the first book (In the Woods), I was hooked: “What I warn you to remember is that I am a detective. Our relationship with truth is fundamental but cracked, refracted confusingly like fragmented glass. It is the core of our careers, the endgame of every move we make, and we pursue it with strategies painstakingly constructed of lies and concealment and every variation on deception…”

And this is what’s most compelling about French’s novels, the slipperiness of her first person narrators, how they’re always just clinging to the edges of things, and totally unconscious of how close they are to falling. The subtlety with which she reveals the true circumstances behind her narrator’s carefully constructed reality, the skilful way she manages to reveal all the things these characters would never, ever tell us. The things these characters don’t even properly know themselves.

I’m reading her fourth novel now, Broken Harbour. (One more title to go before I return the Waitrose bag, and then French has a new novel coming out this fall. And then I fear it’s going to be like Harriet and Amulet, the way she went through the whole series, 1-7, boom boom boom, having no idea that Amulets don’t grow on trees, thinking new ones were an ever-available resource, and now she has to wait an eternity for number 8). And the book is kind of ruining my life, because I can’t stop reading it, staying up far too late and just-one-more-chapter. Because how can I not want to know what happens next?

Both my children are currently undergoing sleep changes and bed experiments and we’re all playing musical beds at our house these days, and the last few nights I’ve been awakened twice or three times before dawn. But I really can’t blame my current stupor on this entirely, on my children. Because the real reason I’m so tired, like words-confusingly tired, should-not-be-permitted-to-operate-a-motor-vehicle tired, is that I’m staying up past midnight reading Tana French, and then even once I manage to put the book down and turn the light off, I’m still immersed in its atmosphere, fearing shadows in the darkness. Awake and lying still, alert to barely perceptible sounds. Perhaps imagined ones. And the distinction doesn’t even matter.

May 1, 2016

The M Word: Ever Since The End, by Christa Couture

This is the fifth in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From previous weeks: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“; “Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self”; “Dear Me, by Nicole Dixon“; “Kerry Clare on Motherhood and Abortion.”

In her essay, “These Are My Children”, Christa Couture introduces readers to her sons, Emmett and Ford, and recounts how she has mothered and related to motherhood since their deaths. Here, she considers what’s changed and what hasn’t in the two years since her essay was published.

*****

Between the time I first wrote “These Are My Children” and the time for final edits before The M Word went to print, the one update I made was to the ages my children would have been, if they were still alive (from six and three to seven and four).

I’m thinking of what’s changed in the time from print to now, and the same update is my first thought: Emmett would be nine, and Ford would be, in a few weeks from now, seven.

When asked to consider what else has changed in this time, I worried that nothing has. Motherhood remains a kind of fixed story for me, one I can still replay from its beginning to end. “The End” was the title of the final blog post where my husband and I kept family and friends updated on Ford’s 14 months of life while he was living. And when I think of my story with my children, “the end” feels almost like the title, not just the last page. I picture it a finished book; I picture that book in a bag that I carry forward into each year of my life.

That hasn’t changed.

I have moved from the city (Vancouver) where my sons’ ashes are interred to Toronto. Thus, I visit that site now, so far, only yearly. When I do, I still place my hand on the shared gravestone, still trace the letters, and still feel comfort in close proximity to their remains, and to the part of my body there.

That hasn’t changed.

When I return to their grave, new gifts have been left on its ledge, from their grandmothers, aunts, father… slow changes to the scenery take place.

In my essay, I had written of the physical record of my children on my own body. The stretch-marked belly remains the same, but the caesarean scar I’ve found comfort in tracing is almost entirely, to the eye, gone, and increasingly fading to the touch. As it fades, the whisper of the ridge of that scar gets quieter: “I am the window he climbed through, into your arms.”

I don’t mind that this fades. And that is a change.

I no longer, as I had written those few years ago, cry daily for them. When I do cry, it is with less distress.

With as much longing, but less panic. This change I am grateful for.

My therapist and I disagreed: he drew a chart, an arc, of grief and pointed to the end, “When is this?”

“Never.”

I argued I will always grieve for my children. He argued it’s an emotion that, like other emotions and like scars, will run its course and fade.

I don’t consider grief negatively. It has slowly become integrated in my body and life, blooming sometimes unexpectedly and otherwise reliably on certain holidays and anniversaries of death and birthdays. Sometimes grief still hurts enough that I gasp for air. Less often, grief still curls me into a ball and I feel blind to anything outside of it. Otherwise, it moves into my chest as a wave and with my hand to my heart and a deep breath, I sway with it until the intensity passes.

I understand better that the intensity passes.

That is a change.

A friend’s baby recently died and I realized that while I knew many bereaved parents, I had met them all after one or both of my sons’ deaths. I had not known it to happen to someone I already knew. I was struck in considering the beginning of what will be a very long journey and in remembering how impossible the first night feels. The first night is the worst one. And then the first week, the first month… how slow and dark time is until the first year when counting starts to become harder to do. How I ached, in early days, for time to pass yet hated that it did—that each day passing only took me further away from my children, putting that event and title “the end” further in the past.

“It’s not that it gets easier, but it does change,” I told this friend, knowing too well that there was nothing I could say that would help.

With her son’s death, I was reminded of having “entered a place in which I could be seen only by those who were themselves recently bereaved,” as described by Joan Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking. I felt, when I first saw my friend, seen in a way I seldom do. I found it comforting, a relief almost, for that part of me that remains hidden (against its need), and then immediately I felt regret: I would rather be lonely in grief considering that understanding can only come through such utter heartbreak.

And, in looking at a beginning after an end, I felt relieved for time passing.

“What place do you go to for strength?” I was recently asked. If time passing is a place, then that is where I have been since I first wrote my essay. I have been writing and singing and crying and moving across the country, and waiting.

And life has changed.

My boys would be nine and seven. I will always count those years and, occasionally, imagine who my boys would be, and would have become.

I will miss them. I will love them.

And that will never change.

**

Christa Couture’s new album is Long Time Leaving. It’s out right now. (Buy it!) She’s currently on a cross-Canada tour.

April 29, 2016

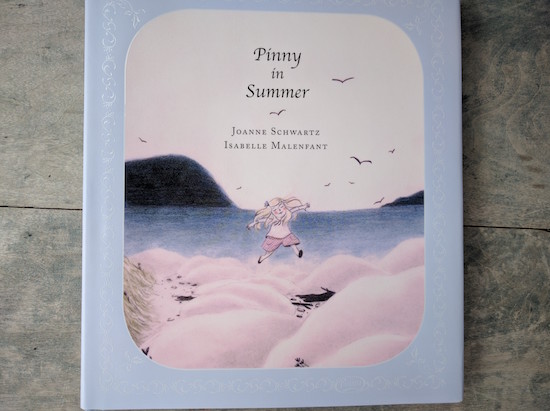

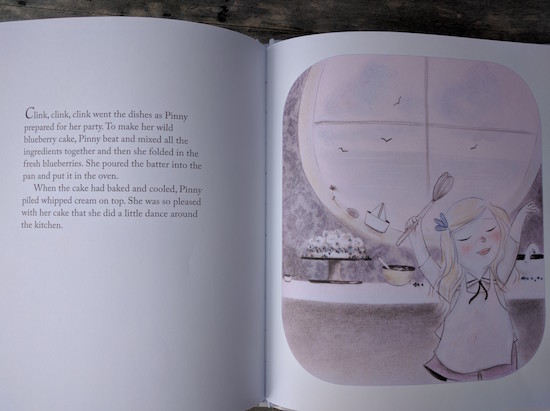

Pinny in Summer, by Joanne Schwartz and Isabelle Malenfant

I owe the most enormous debt to Joanne Schwartz. I met Joanne five and a half years ago when I started attending toddler time at the Lillian H. Smith Library with Harriet, and not only did she introduce me to The Night Kitchen, by Maurice Sendak (which is one of the best things a person can do for anybody), and books by Eve Rice, and Marisabina Russo, and so many others, but she actually taught me how to read a story.

Now I am really, really good at reading stories, but my secret confession is that it’s because I totally stole Joanne’s technique. Which involves talking to children like they’re humans instead of idiots, not employing silly voices, instead a clear voice just not loud enough so that you’ve got to be engaged in order to hear it, and (and this is key) that the voice be thoroughly infused with wonder. So that it’s soothing and animated at once—the most incredible balance.

Joanne’s own books are not so different in approach from the way she reads. She is the author of Our Corner Grocery Store, a fantastic story about a family-run shop , and also of the books City Alphabet and City Numbers, with photographs by Matt Beam, and all of these are books that illuminate the extraordinary in ordinary sights and experiences.

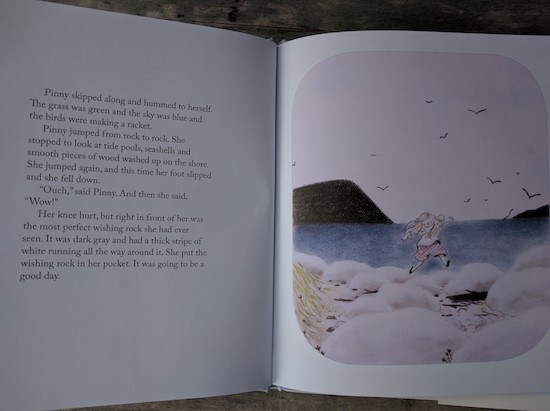

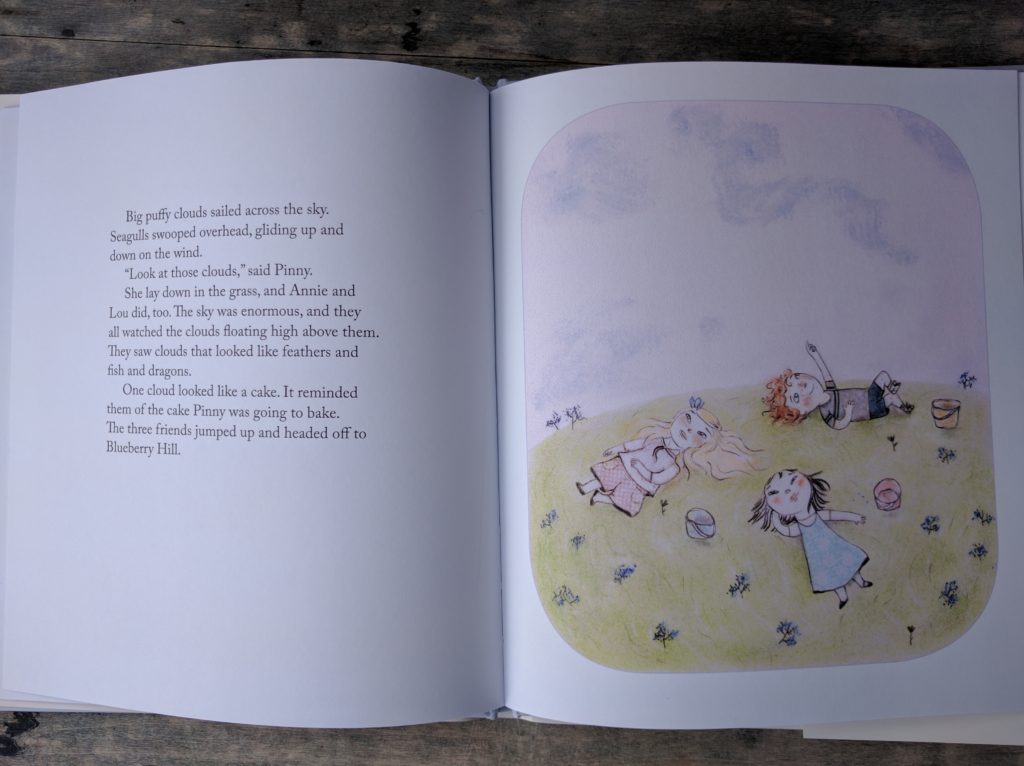

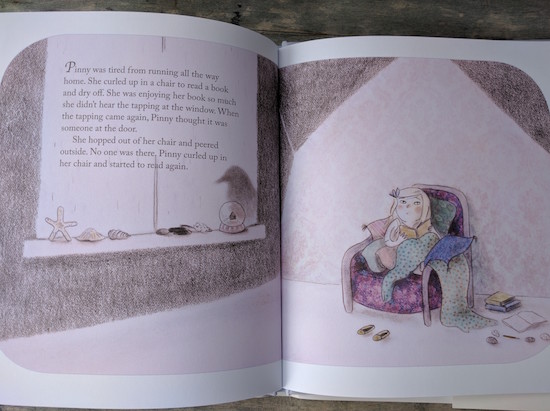

Her new book, Pinny in Summer, gorgeously illustrated by Isabelle Malenfant, fits nicely into that oeuvre, and manages that same balance of soothing and animated, rich with wonder. It’s four little stories in one book, all taking place over the course of a single day—similar in structure to Frog and Toad, or Little Bear. Pinny is a little girl with a whole lot of freedom and so her day contains multitudinous adventures: she finds a wishing stone; she enjoys a session of cloud watching with her friends, Annie and Lou, and then manages to pick a bucket of blueberries before getting caught in a rainstorm. She encounters seagull, then bakes a cake, and it’s around here that it all begins to go a bit wrong—but with a little bit of ingenuity the day is salvaged. And the best thing of all as the sun goes down (and “[t]he sky changed from blue, to a deeper blue, then to dark blue”): there is going to be a tomorrow.

Schwarz’s prose is wonderful—”the sun was shining again, making everything as warm as toast”—and so nice to put your mouth around. Pinny’s adventures are simple but lovely, and are certainly the kind that will inspire a child to dream of similar things. And the story is beautifully bought to life with Malenfant’s illustrations, with shades of blue and violet, simple drawings enlivened by wonderful texture, shadows and darkness at the edges that keep things interesting.

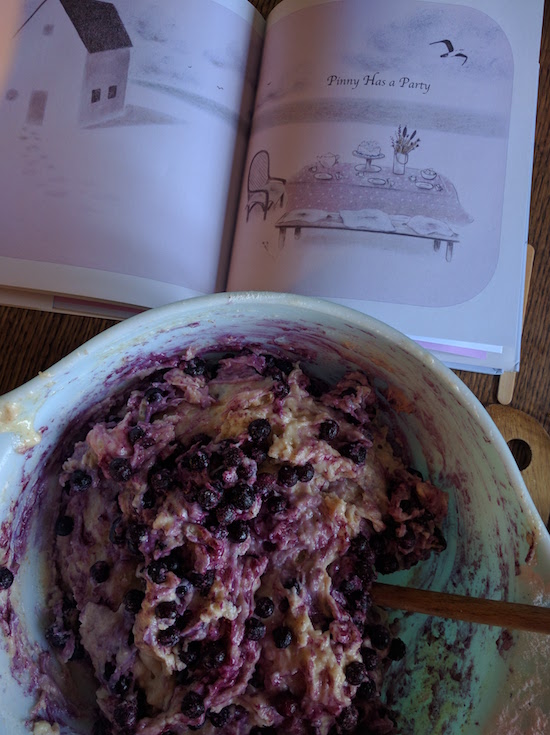

And of course, Pinny in Summer inspired us too. Because I dare you not to read it and want to bake a wild blueberry cake like Pinny does. And so we did, even though our wild blueberries were not picked in buckets on blueberry hill, alas, but came from a bag in the freezer.

All the same though, once we dumped the berries in the mix, the batter turned the same shade of purple as the pictures, which was perfect (and seeing the table set in the image above, you can probably get a good idea of why I love this book so).

The cake was delicious. We froze half for later. And we look forward to spending this summer reading about Pinny again and again.

April 28, 2016

The Name Therapist, by Duana Taha

Often the most remarkable story about names is the fact that sometimes there isn’t a story at all. For example: I somehow managed to be named after two Irish counties entirely by accident. “What where your parents thinking?” people have asked me, imagining me as the offspring of two Munster enthusiasts, but I don’t think they were thinking of much beyond euphony. Although my maternal grandmother had a difference of opinion about that, and suggested “Lea” as a middle name to soften the sound, which was how I came to be called Kerry Lea by everybody on my mother’s side of the family. But I think my father’s family found the double names a bit pretentious (and really, their tendency was to truncate single names to a syllable, so that’s not shocking), so they called me Kerry, and in my mind it was a bit like having two selves, Kerry and Kerry Lea being people entire distinct from each other. (Further: carrying around an extra name is very cumbersome, and I ditched the “Lea” altogether at the beginning of grade one at a very singular moment in which my teacher asked me what I wished to be called, and I proclaimed myself a Kerry and so have been ever since.)

Often the most remarkable story about names is the fact that sometimes there isn’t a story at all. For example: I somehow managed to be named after two Irish counties entirely by accident. “What where your parents thinking?” people have asked me, imagining me as the offspring of two Munster enthusiasts, but I don’t think they were thinking of much beyond euphony. Although my maternal grandmother had a difference of opinion about that, and suggested “Lea” as a middle name to soften the sound, which was how I came to be called Kerry Lea by everybody on my mother’s side of the family. But I think my father’s family found the double names a bit pretentious (and really, their tendency was to truncate single names to a syllable, so that’s not shocking), so they called me Kerry, and in my mind it was a bit like having two selves, Kerry and Kerry Lea being people entire distinct from each other. (Further: carrying around an extra name is very cumbersome, and I ditched the “Lea” altogether at the beginning of grade one at a very singular moment in which my teacher asked me what I wished to be called, and I proclaimed myself a Kerry and so have been ever since.)

So what I mean about names, and what Duana Taha means too in her wonderful new book, The Name Therapist, is that even the names without a story turn out to be stories, and for some of us, those stories are inherently interesting. Name nerds, she calls us. In high school, I owned an A-Z of baby names, just because it made for good reading. I used to collect weird and wonderful names I encountered in books—Beezie from A Swiftly Tilting Planet and Zeeney from Louise Fitzhugh’s The Long Secret were two very bizarre ones I fancied once (and while I didn’t end up naming anybody Zeeney, I named my firstborn after another character in the same book). More often than I ever wrote actual stories as a child, I invented fictional class lists, the names telling me everything about the plots inherent, multiple Melissas, and everything. I made up families too, ones with kids a bit older than me, sisters called Robin, Tracey and Karen—don’t you know exactly who these people are? There was a time in which I wanted to a name my child Ariadne, and about a decade ago, my husband and I had a fictional daughter called Sadie Rose who was very well behaved, and then when I gave birth to actual children, I called them Harriet Joy and Iris Malala, who were not named accidentally at all.

And so for me, reading The Name Therapist was a bit like going to church. Over the years, Duana Taha has established some serious name cred through her column on the blog Lainey Gossip, writing about names, helping expectant parents sort through Ellas and Bellas, and marvelling at phenomena like Jayden, Cayden and Brayden. She continues to explore these ideas in her book, as well as sharing her own experiences growing up with an unusual name, and how her Irish and Egyptian parents’ experiences with their names informed the selection of her name. (Her mother, Mary Veronica, who was only ever, inexplicably, called Maureen.)

The book is a delicious mix of memoir and social science, even better reading than the Baby Name A-Z (which was very good, actually, because it was from there that I first discovered that Zoe meant life, and that Elaine was a variant of Helen). Taha writes about naming trends, sibling matches, “Utah names,” Starbucks names, same-sex couples with the same name, and just what it feels like to be a Jennifer. Taha’s thesis is that a difficult name builds great character, and that learning to be a Myfanwy will make Myfanwy an awesome girl. She’s got a thing against Gords, but don’t take it personally if you are one. She delves into stripper names, African-American names, and why the Baby Name A-Z’s are so ridiculously Anglo-centric. Names and class. Also, what it felt like to be the parent of a child called Atticus during the summer of 2015.

Name therapy is not an exact science, and Taha’s thesis (name as character builder) was disproved more than once throughout her research, but I think that this was never meant to be a controlled experiment. Instead, it’s a book that will be delighted in by most people who’ve ever thought hard about how they were named and why, and what it means to name somebody else. It’s rich with stories, connections, and fascinations. And that I couldn’t write about it without sharing name stories of my own proves Taha’s overarching premise: that names are something it’s hard to shut up about.

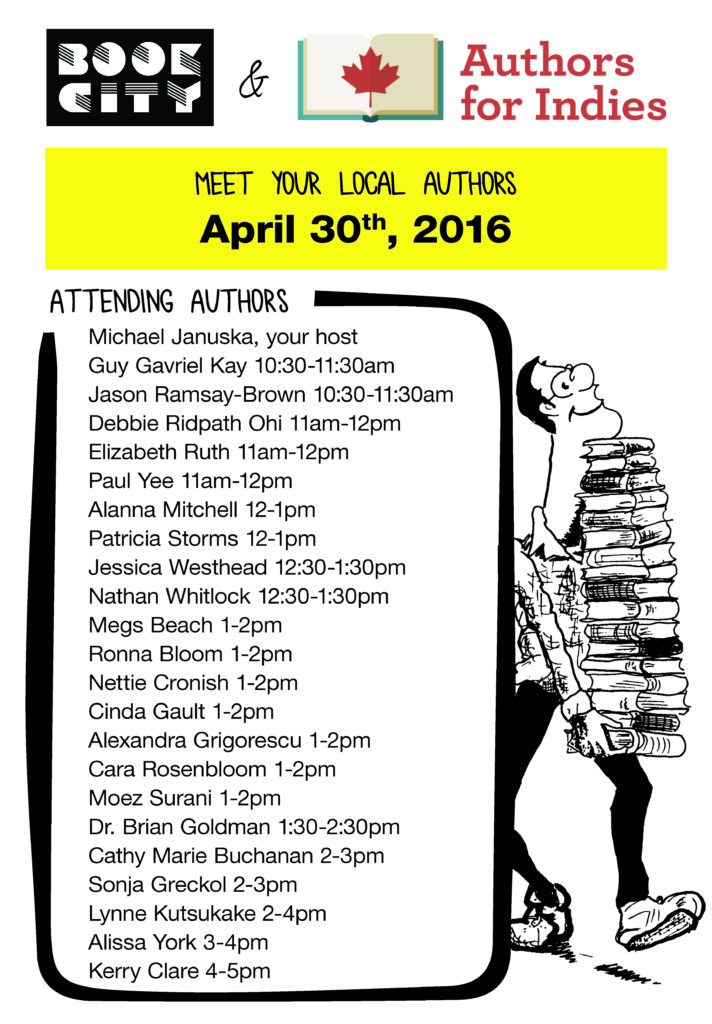

April 26, 2016

Authors for Indies on Saturday

Come and let me sell you all the books. I’ll be at Book City Danforth, and it’s going to be terrific. If you’re not in the neighbourhood, check out the Authors for Indies site to find out what’s going on near you.