May 17, 2016

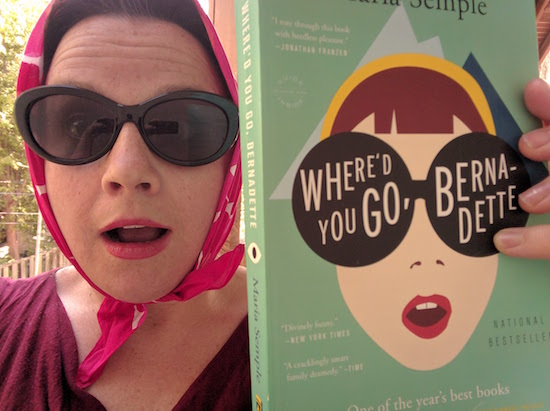

New Maria Semple!!!

I really am this excited about the news of a new book by Maria Semple coming this fall. You can learn more about it and also read an excerpt here. (Yay!!!) Today Will Be Different is out in October.

May 16, 2016

How to Terrorize Your Child with Margaret Wise Brown

We were at the bookstore a few weeks ago, and I couldn’t narrow down my selection of picture books.

We were at the bookstore a few weeks ago, and I couldn’t narrow down my selection of picture books.

“Should we get,” I proposed to Harriet, “The Fox and the Star, by Coralie Bickford-Smith, or The Dead Bird, by Margaret Wise Brown.” I was emphatically waving the latter in the air.

Harriet pointed to the other one. “Why would I want to read a book about a dead bird?”

“Only because it’s a reissued book by a literary icon that dares to confront uncomfortable issues of mortality.”

“No,” she said.

I said, “Why?”

She said, “I don’t want to read books about dead things.”

She was still annoyed about a recent book I’d read her in which the Grim Reaper comes to tea and takes away the children’s grandmother, and everybody understands and feels good about the whole thing. Even though the children appear to left without a guardian. And even though the book doesn’t address the question of death coming for children, or young parents—would we put the kettle on for the reaper then? Though if someone wrote that book, I’d probably make Harriet read it too.

“So we’re getting The Dead Bird,” I told her. The illustrations are beautiful—by the award-winning illustrator of Last Stop On Market Street— and normalizing death is healthy and wasn’t there a dead bird in Sidewalk Flowers by Jon-Arno Lawson and Sydney Smith? And everybody liked that book.

And Harriet said, “No.”

“The Dead Bird,” I said.

She said, “No dead bird.” And she seemed kind of immoveable, so I didn’t want to push it.

Two weeks later, we were at the library and I saw The Dead Bird on the new releases shelf.

“Now isn’t that lucky,” I said. “A brand new copy of The Dead Bird, and nobody else has picked it up yet. It must be fate. The book was meant for us.”

“Do you think nobody has picked it up,” said Harriet, “because nobody would ever, ever want to read it?”

But I pooh-poohed her. Dropped the book into our library bag. A red-letter day—we’d brought The Dead Bird Home. What a find!

I told her, “I can’t wait to read this.”

She said, “I can.”

I told her, “Just wait. It’s about death. And dying! Come on, you’re going to like it.”

“I won’t,” she said.

I said, “You’ll see.”

Today I told her, “I’m writing a blog post about you reading The Dead Bird.”

She said, “I’m still not going to read it.”

“But how am I going to write the blog post if you don’t?

She told me, “I read it already, actually. By myself.”

“And did you like it?”

She said, “No. It’s about a dead bird. What’s to like?”

I admitted to her, “You know, the New York Times Book Review shares your assessment of it. And of the Grim Reaper book also.”

She said, “I told you.”

I said to her, “Who are you? Are you even my child? Ursula Nordstrom would be rolling in her grave if she could hear you right now.”

And she said, “Yeah. And then Margaret Wise Brown would go ahead and write a picture book about it. And then wouldn’t you like to go and try to make me read that too.”

“You’re not going to let me read you The Dead Bird then.”

And Harriet said, “No.”

May 15, 2016

A Pillow Book, by Suzanne Buffam

In the notes for Eula Biss’s On Immunity: An Inoculation, the author writes about the other mothers with whom she found herself “in constant conversation” after she became a mother herself, “and the subject of our conversation was often motherhood itself.” (My experience of these same conversations inspired a book, as I wrote about in my foreword here.) Biss writes, “These mothers helped me understand how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are.” And so it meant something to me that Eula Biss is one of the people acknowledged in A Pillow Book, by Suzanne Buffam (whose first book won the Gerald Lampert Prize and whose second was a finalist for the Griffin Prize), that Biss included Buffum in her own acknowledgements as one of the friends by whose conversations her own writing was fed, to consider that A Pillow Book was born of those conversations from the other side.

In the notes for Eula Biss’s On Immunity: An Inoculation, the author writes about the other mothers with whom she found herself “in constant conversation” after she became a mother herself, “and the subject of our conversation was often motherhood itself.” (My experience of these same conversations inspired a book, as I wrote about in my foreword here.) Biss writes, “These mothers helped me understand how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are.” And so it meant something to me that Eula Biss is one of the people acknowledged in A Pillow Book, by Suzanne Buffam (whose first book won the Gerald Lampert Prize and whose second was a finalist for the Griffin Prize), that Biss included Buffum in her own acknowledgements as one of the friends by whose conversations her own writing was fed, to consider that A Pillow Book was born of those conversations from the other side.

Although Buffam’s book is not obviously a companion to On Immunity. At first glance, it has more in common with Jenny Offill’s novel, Dept. of Speculation, a novel in fragments whose form suits the disintegration of the protagonist’s marriage, career and sense of self after she becomes a mother. The novel has been celebrated for its frankness in addressing that kind of disintegration, although my struggle with the book was with its failure to really be a novel. Whereas Buffam’s book is catalogued as poetry, and we’re told within the book itself (as well as on its back cover): “Not a memoir. Not an epic. Not an essay. Not a spell. Not a shopping list. Not a field report. Not a prayer. Not a dream book. Not a novel…” A far more interesting book for its lack of imposition of structural constraint.

While On Immunity is certainly apart from these, a volume of rigorous non-fiction, I think the three books form a fascinating trinity. When I am trying to persuade a reader to pick up Biss’s book (because not everyone is always up for rigorous non-fiction), I tell them that this is the kind of rigorous non-fiction a woman writes when she has a small child. It’s a short book, created of manageable pieces. You could pick up the book and read a section every time you feed your baby, is what I mean. So in a way while it’s decidedly coherent, On Immunity is structurally as fragmented as the others. Furthermore the whole premise is that Biss is trying to make sense of a world that has been exploded to pieces, to reconcile polarities and complexities, to put the pieces back together. Which is what Offill and Buffam are doing as well, and I wonder if together these books suggest a new genre of mother-lit, books that use structure and content to interrogate and complicate the narratives we’re handed about what motherhood is supposed to be and who mothers are and what we’re supposed to preoccupied with. All three books also blend autobiographical elements with fiction (or non-fiction in the case of Biss) in ways that further complicate the narrative and allow the author a necessary expansion of literary possibility.

(Sarah at Edge of Evening wrote this week about Her 37th Year: An Index, by Suzanne Scanlon, and after I read her post, I immediately ordered the book from the publisher. I have a suspicion that this book too might fit [but not comfortably; there are is nothing comfortable about these books] into the genre I’m talking about.)

Buffam’s collection has been born of a certain panic. The first: she’s unable to sleep. In lieu of counting sheep, she’s making lists, strange connections, pursuing fascinations, and becoming preoccupied with sleep hygiene. Plus pillows. “Among the oldest living pillows in the world today is a smooth block of unpainted wood with a wide crack running through its middle and a shallow indentation on the top,” the book begins. The next fragment of text starts, “F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote lists. Abraham Lincoln took midnight walks…. I put a piece of paper under my pillow at night, and when I could not sleep, I wrote in the dark, wrote Henry David Thoreau, who once spent a fortnight in a roofless cabin with his head on a pillow of bricks.”

Lists such as, “Books I’d Like to Read Someday,” “Dream Jobs” (the fragment above which is a piece beginning, “Later that fall in West Orange, New Jersey, Thomas Edison staged the first pillow fight ever recorded on film.”), “Unendurable” (“Dinner with donors./ Dreadlocks on a WASP.”), and “Dubious Doctors” (“Dr. Feelgood/ Dr. Doolittle/ Dr. Spock../Dr. Pepper./ Dr. Dre.”), “Moustaches A to Z” (Anwar Sedat and Burt Reynolds to Yosemite Sam and Zorba the Greek).

The fragments are divided by small circles whose shadings progress in the way of the lunar cycle (as in the cover of the book). And amidst all these other curiosities are dispatches (though “not a dispatch” is probably also true) from the field of motherhood, the narrator’s young daughter referred to as “Her Majesty:

“No luck with the potty today I record in my little blue pillow book. No interest, either, in wearing the new Hello Kitty underwear I bought last week at Target, though Her Majesty did kiss each pair as we removed them from the shiny plastic packaging.”

“Was Shonagon bored? Was she lonely?” Buffum’s narrator wonders of the Japanese author of the first Pillow Book, another object of fascination. We see her husband meeting with a student to discuss her paper on Spinoza: “From the hovering basket of a hot-air balloon in our front yard…the lift off into a swirling swarm of downy flakes, leaving me behind with Her Majesty in the kitchen…” Early in the book, moons before, she recalls sharing sushi “with a famous aging editor in New York.” When he learns she has no children (yet), he tells her, “Good…You’ll be finished as a writer if you do.”

As I said, this is a book that is born of panic.

And it’s fascinating, so readable. It got to the point where I had to put my bookmark onto the following page without turning it over because if I hadn’t, I would have read the page, devouring the whole book in a sitting, when it felt so good just to eke it out, a few pages before bedtime. A book truly to savour. Because the contents are so strange and interesting, ever surprising, and the language is beautiful. I kept reading parts out loud to my husband, and it was then that the poetry of the prose, Buffam’s attention to language was most clear, with subtle rhymes, alliteration. A sense of rhythm. A sense of humour most of all.

May 13, 2016

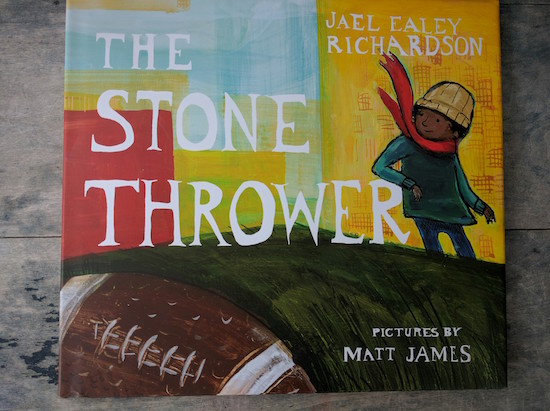

The Stone Thrower, by Jael Ealey Richardson and Matt James

Because this is the week that began with The Festival of Literary Diversity, it only seems fitting to end it with The Stone Thrower, a brand new picture book written by The FOLD’s executive director, Jael Ealey Richardson and illustrated by Matt James (of the award-winning I Know Here). Richardson has told the story before of how an impetus for the festival was her experience promoting her first book, a non-fiction biography of her father, CFL Quarterback Chuck Ealey, and having an indie bookstore owner decline her invitation to visit with the explanation, “This town is very white.”

“There are so many gatekeepers – publicists and sales reps, and bookstore owners, and all these people have to buy into the story in order for you to have any chance,” Richardson explained in her interview with Quill & Quire, and The FOLD emerged as part of an effort to find a way to change that. And now The Stone Thrower is the other creation that Richardson has brought into the world this spring, her father’s story told in picture book form, and it’s every bit as extraordinarily good.

The first time I finished reading this book to my children, we closed the cover a little bit breathless.

“That was really good,” said my oldest daughter, and we made sure to read the book again at night before bedtime so that her dad could know just what we were talking about.

He was also very impressed.

And what do I mean by the fact that this is a book that took our breath away? Because we read a lot of books. We know from good. But rare is the book like this one, with a moral tone as gripping as its story, full of suspense and ultimate triumph, spots of humour, rich and warm illustrations, and prose that feels wonderful in your mouth when you say it.

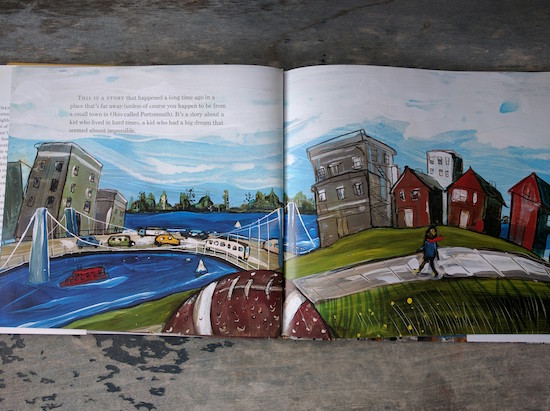

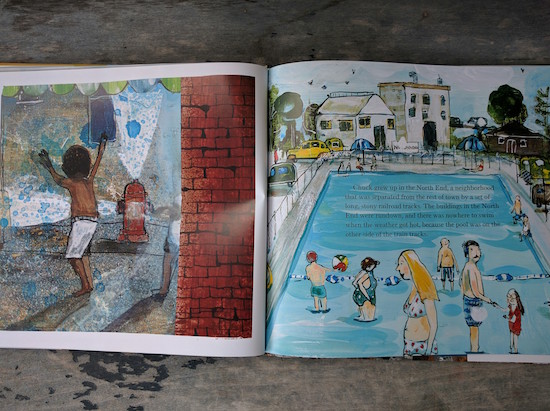

It is the story of a boy called Chuck who grew up in Portsmouth, Ohio, during the 1950s. “It’s a story about a kid who lived in hard times, a kind who had a big dream that seemed almost impossible.” And the odds are against Chuck, a Black kid growing up on what was literally the wrong side of tracks. James’ illustration shows Portsmouth’s white residents cooling off on summer days in a swimming pool, while the kids on the North End, like Chuck, played in the spray from opened-up fire hydrants. Chuck’s mom works hard, but she dropped out of school when she was young and makes very little money. She wants a different kind of life for her son.

“Those coal trains that come through, they don’t stop here,” she said. “I want you to be just like that. Do you remember where you’re going, son?”

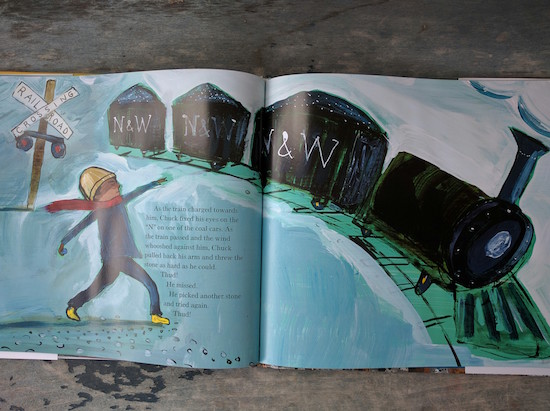

While walking down by the tracks, Chuck picks up a stone as the train comes by. Richardson makes her story rich with atmosphere: “The ground began to rumble, and the train tracks shook. The stones along the tracks jumped and bounced like hot kernels of popcorn.” Chuck aims for the N on the N&W on the boxcars (for Norfolk and Western), and throws. And misses. And misses again. But as the last car chugs by, he tries one more time: “BANG! Chuck smiled and raised his hands in victory.”

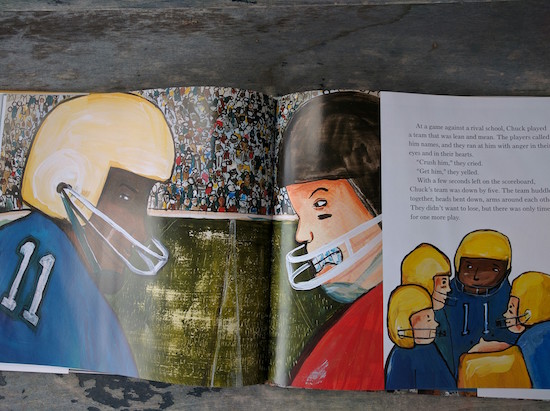

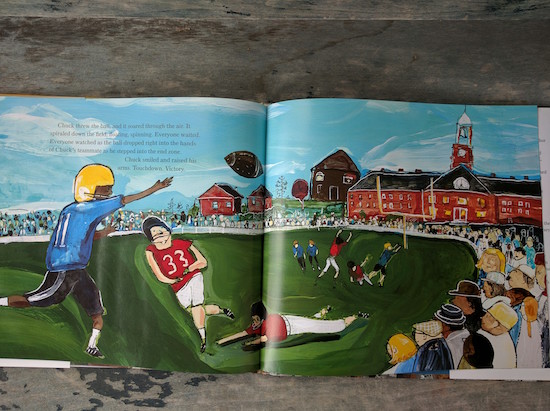

And this kind of persistence becomes emblematic of Chuck’s experience both in school and in football too, paving the way to his success as quarterback of the school football team. At games, he faces taunts from rival players because of the colour of his skin, but Chuck doesn’t let this break his focus from the object of the game, which is to connect with his teammates and win. And he does. The final words of the story: “Touchdown. Victory.”

The story is made all the more poignant with Richardson’s author’s note at the end of the book, which explains that Chuck Ealey won every game as quarterback of his high school team, and received a scholarship to the University of Toledo, where he won every game there. But after graduating with his college degree (“the best of all his victories”) he finds himself unable to play professional football in America, because the idea of a Black quarterback was still unfathomable to the powers that be.

So he moved to Canada, and played in the CFL, leading the Hamilton Tiger-Cats to the Grey Cup in his very first year. “It’s an unbeatable story that amazes me,” writes Richardson, “even though I’ve heard it all before, because Chuck Ealey happens to be my father.”

In Richardson’s Quill and Quire interview, Groundwood Books Publisher Sheila Barry underlines the need for more contemporary Black figures to inspire young kids: “We have Viola Desmond, but that was a long time ago.” Although obviously, this is a book that will appeal to readers regardless of the colour of their skin.

Together, Richardson and James have hit a target of their own: that of a really great story. And they totally nailed it.

May 12, 2016

Throwback Thursday

I was a compulsive photographer and documenter of days long before I’d ever heard of social media, although it’s true that I didn’t photograph my lunch back then. But it’s true that I used to take photos of everything and everybody, evidence of this being picture after people of lined up in a row looking awkward and confused about just why I am taking their pictures. People sitting around a table looking unimpressed seemed to be my primary focus as a photographer, although I think they’d been happy and engaged enough until I pulled my camera out, this being, of course, why I wanted to take the picture. To capture something. As if that was even possible, and it makes me things of the drawers in Joan Didion’s New York apartment in Blue Nights stuffed with envelopes and documents and things that she imagined could keep her from losing the people she loved. I have engaged with that book, in all its messiness and imperfections, in a way that I haven’t with The Year of Magical Thinking. I say “haven’t” because I imagine that I will some day, that like with Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work and motherhood, one day my universe will shatter and I will finally understand what Didion is talking about about. Not that I’m counting down to that. But I understand the impulses of Blue Nights so innately, and not just because it’s May and the nights are blue and we’re coming up to the solstice. And my urge to capture and keep everything that happened to me back in those days between the ages of 16 and 23, say, ultimately would come to nothing. It was always going to be like that.

I was a compulsive photographer and documenter of days long before I’d ever heard of social media, although it’s true that I didn’t photograph my lunch back then. But it’s true that I used to take photos of everything and everybody, evidence of this being picture after people of lined up in a row looking awkward and confused about just why I am taking their pictures. People sitting around a table looking unimpressed seemed to be my primary focus as a photographer, although I think they’d been happy and engaged enough until I pulled my camera out, this being, of course, why I wanted to take the picture. To capture something. As if that was even possible, and it makes me things of the drawers in Joan Didion’s New York apartment in Blue Nights stuffed with envelopes and documents and things that she imagined could keep her from losing the people she loved. I have engaged with that book, in all its messiness and imperfections, in a way that I haven’t with The Year of Magical Thinking. I say “haven’t” because I imagine that I will some day, that like with Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work and motherhood, one day my universe will shatter and I will finally understand what Didion is talking about about. Not that I’m counting down to that. But I understand the impulses of Blue Nights so innately, and not just because it’s May and the nights are blue and we’re coming up to the solstice. And my urge to capture and keep everything that happened to me back in those days between the ages of 16 and 23, say, ultimately would come to nothing. It was always going to be like that.

(For me everything hinges on 2002. I met my husband that year and stopped longing, and have been more or less happy ever since. Everything that ever happened before that year mostly mortifies me to consider now. And I wonder if I was able to shrug off my impulse to document it all and keep everything because from that point on I had someone with whom I could verify that all of these things actually happened. Another idea: that the internet took over my life that year and I started capturing everything online. And that I’m just as a compulsive a documenter as I ever was, and well, you’re kind of reading the evidence of that.)

The other night I had occasion to sort through my boxes of photographs upstairs. I have one from high school and the other from university. There used to be many, many more photographs, but I did a cull about a decade ago because there are only so many photos a person needs of her boyfriend from grade eleven, though I did not think so when I posed for those shots. And what I realized the other night as I was looking through photos from my university years is most of these photos signify nothing now. There are people I love and unbelievably bad haircuts, and I continue to be baffled by everything I ever wore. The decor of all of my bedrooms is also unfathomable: throughout those years I had either a Spice Girls or John Travolta as Vinnie Barbarino post above my bed at all times, plus inspirational quotes written in marker on index cards, an album cover with a picture of Nana Mouskouri on it, and a campaign poster for John F. Kennedy. It was kind of a weird aesthetic.

And maybe I knew it was always going to get lost. Perhaps it was never about capturing and keeping, but instead about evidence that any of it had ever been. That if it weren’t for the photos, I’d never believe in a room like that, and I’ve got the pictures and I still don’t. And I see my friends and I with our arms around our shoulders in rooms that I don’t recognize, places where I’m sure I’ve never been. There are people in those photos who mean nothing to me now. And there are holes in my memory as big as oceans—did you know that I saw Prince on stage with Sheryl Crow at the Lilith Fair in 1999? I didn’t. I still don’t, really. And even the stranger things, like the photo from my 22nd birthday party, me and three other people, and two of them are dead. Or that during the 2000/2001 school year, I lived in an apartment with a huge black and white photo of the New York City skyline at night hanging over the fireplace. The World Trade Centre, but I never even knew what those towers were called until five months after I’d moved out of there and into another apartment, until the towers were gone and we sat on our roof that night watching the CN Tower gone dark.

And maybe I knew it was always going to get lost. Perhaps it was never about capturing and keeping, but instead about evidence that any of it had ever been. That if it weren’t for the photos, I’d never believe in a room like that, and I’ve got the pictures and I still don’t. And I see my friends and I with our arms around our shoulders in rooms that I don’t recognize, places where I’m sure I’ve never been. There are people in those photos who mean nothing to me now. And there are holes in my memory as big as oceans—did you know that I saw Prince on stage with Sheryl Crow at the Lilith Fair in 1999? I didn’t. I still don’t, really. And even the stranger things, like the photo from my 22nd birthday party, me and three other people, and two of them are dead. Or that during the 2000/2001 school year, I lived in an apartment with a huge black and white photo of the New York City skyline at night hanging over the fireplace. The World Trade Centre, but I never even knew what those towers were called until five months after I’d moved out of there and into another apartment, until the towers were gone and we sat on our roof that night watching the CN Tower gone dark.

Maybe it’s not the photos that turned out to signify nothing that so fascinate me, but instead the ones that ended up telling stories so different from those I thought I was telling at the time.

May 11, 2016

13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, by Mona Awad

I wasn’t expecting to struggle with Mona Awad’s debut, 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl. The day I bought it, I met up with two friends who both happened to be in the middle of the book and they said it was great. It’s been receiving rave reviews. But as I began to read it, I couldn’t help but find it unsettling, and not just in the ways it was intended to unsettle. Part of the problem is entirely my own—I’ve had a hard time reading most of the books I’ve picked up in the last couple of weeks. Part of the problem too was with the book’s design, the unfinishedness of its stark design and its lack of heft. Was lack of heft the problem? Ironic. I did keep thinking that I’d read a version of this book a long time ago, and it had been called A Girls Guide to Hunting and Fishing. Was I being chick-lit-ist? But then Awad’s Elizabeth is definitely no “chick.” There’s nothing pink about this book. The only shoe you’d put on this cover would be an army boot, but maybe that was the trouble—Elizabeth the teen goth all in black, maudlin and sad. A bit like the actual cover then, rough outlines, scrawled. Maybe that was the problem too.

I wasn’t expecting to struggle with Mona Awad’s debut, 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl. The day I bought it, I met up with two friends who both happened to be in the middle of the book and they said it was great. It’s been receiving rave reviews. But as I began to read it, I couldn’t help but find it unsettling, and not just in the ways it was intended to unsettle. Part of the problem is entirely my own—I’ve had a hard time reading most of the books I’ve picked up in the last couple of weeks. Part of the problem too was with the book’s design, the unfinishedness of its stark design and its lack of heft. Was lack of heft the problem? Ironic. I did keep thinking that I’d read a version of this book a long time ago, and it had been called A Girls Guide to Hunting and Fishing. Was I being chick-lit-ist? But then Awad’s Elizabeth is definitely no “chick.” There’s nothing pink about this book. The only shoe you’d put on this cover would be an army boot, but maybe that was the trouble—Elizabeth the teen goth all in black, maudlin and sad. A bit like the actual cover then, rough outlines, scrawled. Maybe that was the problem too.

My problem with 13 Ways of Looking Like a Fat Girl was one that interested me, which is vastly different from most books I have a problem with. The problem I have with most books is that they don’t interest me at all, but this wasn’t the case here. It was totally bizarre. Here I was getting hung about a book because its protagonist was so unlikeable—which says way more about me than that protagonist. What kind of a reader am I? Only the kind of reader who usually considers herself above such critical assessments. Unlikeable, piffle. But I couldn’t shake it here. Elizabeth, I wanted to say to the girl, cheer the fuck up. It can’t all be that bad. Wash off all that unfortunate eye makeup and go out into the sunshine.

Part of my problem with 13 Ways of Looking Like a Fat Girl was personal. In general terms, to be a woman is to be afflicted with a mild case of body dysmorphia, and this inability to grasp one’s own bodily reality for me hasn’t been aided by the three times I’ve lost about 30 pounds in the last 20 years (only once through trying really hard; there was also the time I moved to Japan and the other when I stopped breastfeeding) or the two times I’ve gained 30 pounds in pregnancy, not to mention the other times I’ve gained 30 pounds without any real explanation (except for that one time, which was all down to moving to England, eating a lot of sausage [not a metaphor, you sick dog] and being in love). So you see, I know what it is not to know one’s own body. And so the stories that were fixed in Elizabeth’s perspective unnerved me then. Was she really fat? How fat? And did it even matter? Of course it did. But it doesn’t too. So my unsettlement here is a testament to Awad’s achievement of giving her reader such a feeling of the claustrophobia one can experience living inside a body. Some of it was just all too familiar.

Some of it really was that Elizabeth was also kind of annoying though. Which would be fine, except I think that what I mean by complaining that the character is unlikeable is actually that her lack of evolution is just not very interesting, from a literary point of view. Although it is interesting that so much remains stable for her even as she loses weight—this is quite deliberate on Awad’s part. The novel’s epigraph is from Margaret Atwood, Lady Oracle (I think?): “There was always that shadowy twin, thin when I was fat, fat when I was thin.” At any size, really, the song remains the same.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. And while it is also to Awad’s credit that this is not a heartwarming story about a woman’s struggle overcome adversity and finally accept herself (blech), I wanted something more for the character than what was written. As a kind of stand-in for actual evolution, Awad has Elizabeth changing her name as the book progresses, employing the various possibilities inherent in a name like that. But that literary strategy seemed kind of facile, because I didn’t know Elizabeth well enough to understand what it was she was striving for with her new names, what each one meant.

There is a dawning awareness though. The reader sees this in the story “Caribbean Therapy,” in which Elizabeth goes to a really terrible nail technician, incredulous of the woman’s reality—that here is a fat woman who loves and is loved and is happy. And then in the story “Additionelle,” with its stunning, awful, claustrophobic ending. That she’s trying and trying but not getting any closer to the person she is trying to be, to become. And finally in the last story, “Beyond the Sea,” in which she’s coming to realize the futility of her struggle, that we get one life and why should it be such a struggle, unless you’re Karl Ove Knausgård of course. (I think about this a lot, actually. Not about not being Karl Ove Knausgård, I mean, but that I am 36 years old and I refuse to to spend the next forty years of my life fighting, trying to be less, losing, and then losing again. I refuse to be 70 years old and hating myself because I’m fat. For that matter, I refuse to be 36 years old and hating myself for being fat. And am I fat? How fat? No. I refuse to engage. I’d rather eat a croissant. I’d rather take a walk.)

And then the ending of this story, the final line of the book: “As I watch her [a woman peddling on a stationary exercise machine]… I feel dangerously close to a knowledge that is probably ours for the taking, a knowledge that I know could change everything.” And it was here that I wanted to cheer: Yes, yes, take it, Elizabeth. Because that knowledge is right there. Everything I wanted from this book, for this character, summed up in a line. And it’s a credit to Awad too that all possibilities are wide open right here.

Being happy and fat (and what is fat? how fat? etc. etc.) is not a given, but that knowledge that is ours for the taking seems very much of this moment. Just this morning I read Kaye Toal’s article, “I Promise You Don’t Have to Lose Weight to Be Happy” AND Dr. Yoni Friedoff on how liking the life you’re living is the best way to have a heathy weight, AND just yesterday, Lindy West on how to be a happy fat woman. There are very few ways in which I can say that right now is a glorious time to be living as a woman inside a body, but with such zeitgeist this may be one of them. And it feels good.

I hope that Mona Awad’s character gets the memo too.

May 9, 2016

The Festival of Literary Diversity

Warning: There’s gonna be typos, as I translate my pages and pages of handwritten notes into a blog post. Forgive me, please?

From the start, The Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD) seemed to me like a most inspired idea, one whose time was exactly right, although my enthusiasm was mostly theoretical. Because, and here’s my confession, for all my lit championship, there are few events I’d choose to attend over, say, staying home and reading. I don’t need to discover new books and authors, I feel connected enough to the literary scene, and I’d rather read an author’s work than hear her answers at a Q&A.

But then the FOLD rolled out their schedule, and I was as excited as I was impressed. Not only did it seem like something I should go to, but now I actually wanted to. I’ve been going to literary festivals for years, but these were panels apart from anything I’ve ever attended before. These sessions were asking questions whose answers I had no idea about—what an incredible opportunity for learning. There were also writers whose work I was familiar with, but others I hadn’t encountered before. I knew that I absolutely had to be a part of it, and it was pretty easy to find three writer friends who wanted to come along.

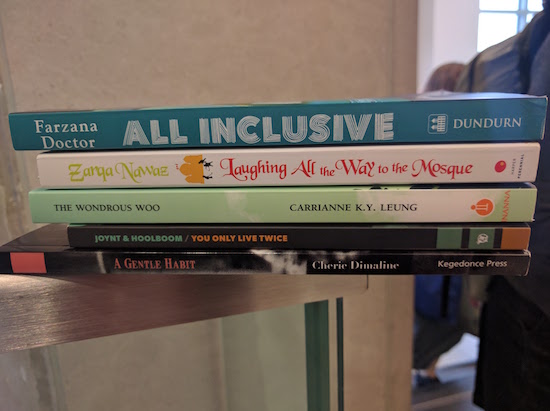

Although we took a wrong turn off the 410, so were late for the Faith and Fiction panel. As we walked in, Zarqa Nawaz (author of the memoir Laughing All the Way to the Mosque and an actor from the TV series Little Mosque on the Prairie) was discussing the universal struggle for social justice, how it was not just particular to faith communities. She gave the example of women who are restricted from attending school in France because of wearing religious dress—secular and fundamentalists both, she explained, are capable of denying a woman eduction due to dogmatic beliefs.

Although we took a wrong turn off the 410, so were late for the Faith and Fiction panel. As we walked in, Zarqa Nawaz (author of the memoir Laughing All the Way to the Mosque and an actor from the TV series Little Mosque on the Prairie) was discussing the universal struggle for social justice, how it was not just particular to faith communities. She gave the example of women who are restricted from attending school in France because of wearing religious dress—secular and fundamentalists both, she explained, are capable of denying a woman eduction due to dogmatic beliefs.

Cherie Dimaline (an award-winning Métis writer whose most recent book is the short story collection A Gentle Habit) told us that for her, stories themselves were a faith, and that repetition was used in storytelling as a way to keep the stories, “to develop the brain like a beehive,” she said. She’d been selected in her family when she was young as a story-keeper and her responsibility in this respect is to the seven generations before and after her, to reach back and also reach forward.

Ayelet Tsabari (author of The Best Place on Earth) continued this connecting of faith and story. In order to write, she explained, you need a tremendous amount of faith—in one’s self, in the reader and also in the possibility of fiction changing the world even in the smallest ways. “You can write fiction without faith,” she said, “but it’s much harder.” And then she noted how for her, writing was very much a spiritual practice, with ritual, an insistence on objects, and a whole lot of praying. “Aside from parenthood,” she explained, “[writing] is the one thing I take seriously, where I find meaning.”

Nawaz talked about Muslim women and victim literature. “A boring suburban life was really radical for a Muslim woman,” she noted. In publicity for her work, she finds herself being defined as someone belonging to a violent faith that doesn’t believe in comedy. She tries to find a way to talk about her community in ways that are fair and also challenge stereotypes. An interviewer in the US mentioned responses to Little Mosque on the Prairie, and Nawaz countered that with Christian responses to the film The Last Temptation of Christ, or the furor when Sinead O’Connor ripped up a photo of the Pope on TV. “There’s cultural amnesia,” she said. “The examples are everywhere.” The stereotypes are so entrenched, but it ultimately it all comes down to the fact that people everywhere are all the same.

Dimaline continued the thread about stereotypes and their entrenchment. People, she said, can be upset when their expectations are disrupted. Her novel, The Girl Who Built a Galaxy, begins with a girl and her grandfather, familiar territory for a Indigenous story. But then it takes a twist and the girl ends up in New Orleans, which threw a few readers. “‘Where’s her canoe?'” Dimaline has her hypothetical reader asking, answering that reader’s question with, “You know, we also exist outside your imaginations.”

“Writing,” says Dimaline, “is the last true magic. Imagine being able to create something out of nothing,” and that something is what literature is. It takes faith to create it, and also to receive it.

Moderator Eufemia Fantetti asked about criticism of writers’ portrayal of faith. “I try to listen to feedback,” answered Vivek Shraya, the multidisciplinary artist whose latest book is the poetry collection even this page is white. The feedback is not always useful, but can be, says Shraya, as she embarks in work like her recent work, She of the Mountains, which reimagines Hindu mythology through a feminist lens. She went on to talk about the importance of not underestimating one’s audience. It’s been tricky having a book about queerness with “God” in the title, but sometimes, she said, you have to trust your muse. And people have connected with these stories in all kinds of surprising ways. Diverse books are important because people get to see their own experiences reflected, but these books are also good for readers who can connect with different perspectives.

Tsabari said that the story she was most afraid to publish for fear of controversy (the story of an Israeli woman who comes to Canada to meet her new grandchild, and discovers the boy will not be circumcised) was the one which has received the most overwhelming emotional response. That often a writer has to write about what scares her. And the stakes seem even higher now as her book is about to published in Canada. “It’s all scary,” she said. “That’s why we need faith.”

Both Nawaz and Dimaline talked about how the threat of right-wing tyranny has galvanized their respective communities, Nawaz in response to 9/11 and Dimaline with Idle No More, and has had Muslim and First Nation communities come out of isolation and begin to engage, to shape their own narrative after years of invisibility.

Next up was the Powerful Protagonists Panel with Brian Francis (Fruit, Natural Order), Sabrina Ramnanan (Nothing Like Love), Waubgeshig Rice (Legacy), and Heather O’Neill (The Girl Who Was Saturday Night, The Daydreams of Angels). Each author read from their recent works, and then a discussion began, moderated by Aga Maksimovska.

Next up was the Powerful Protagonists Panel with Brian Francis (Fruit, Natural Order), Sabrina Ramnanan (Nothing Like Love), Waubgeshig Rice (Legacy), and Heather O’Neill (The Girl Who Was Saturday Night, The Daydreams of Angels). Each author read from their recent works, and then a discussion began, moderated by Aga Maksimovska.

His own powerful protagonist, said Francis, was born of his interest in older generations and the way they kept private and personal stories close, linked to pain and shame. What if, he wondered, he wrote a character who tried to escape from that?

Ramnanan’s protagonist was one who, after a sudden fall from grace, was surprised to discover she was vulnerable, that as a woman she was forced to adhere to different standards than the boys were. She is disgraced and then furthermore when she learns that the man she loves is going to marry somebody else. And she achieves her power when she makes the decision to go and confront that woman her love is due to marry, and in doing so changes the course of her life and also that of the people in her village

Rice’s character in Legacy is one who is powerful because she doesn’t believe what the world tells her about herself and her people, and because she carves out a path for herself, coming to the city to pursue an education at a time when this wasn’t common for First Nations women, thereby laying a path for future generations.

O’Neill said that her fascination is with protagonists who have to learn how to be themselves in surprising contexts, in the midst of narratives where they mightn’t feel that they belong. “We are not our contexts,” she said. “We strive against our contexts.”

The writers talked about when their protagonists are a little them, and also about the opportunity to live vicariously through their characters. In response to the question of character likability, Francis commented that it’s so much more important that characters be interesting. Ramnanan would prefer her characters be memorable. Even if a reader doesn’t like a character, said Rice, at least the character is invoking a reaction. And O’Neill said that for her as a novelist, creating likeable characters is a driving force. She sets challenges for herself of making the most unappealing characters loveable—and through that, the reader can have a growth experience.

They talked about characters as witnesses, and whether or not it’s easier or harder to write a character who is more or less like you, and whether plot comes first or character (and the answers were varied). They were asked about building a character’s strength, and O’Neill said that she likes to start her characters so far down that there’s nowhere for them to go but up. Francis considered the question of whether a character must necessarily triumph. And what kind of characters do they struggle with? O’Neill has never been able to write a mother; Rice was nervous about writing in the perspective of a woman, but drew from the women around him to get it right; Ramnanan has more trouble writing about experiences closer to her own than writing wholly imagined ones; and Francis said that he’s conscious of writing about family—that everyone imagines himself the hero of his own story, and it disturbs everything when a writer goes and upsets that narrative.

And then we broke for lunch! There were several options right there in the venue (which was fantastic, by the way, as was the organization of the event and how completely wonderful it was to be there) and we ended up having wraps and salads. After that was a browse in the pop-up bookstore, which was being put on by Orangeville’s Booklore. And then we needed tea, of course, so we went exploring historic downtown Brampton (including a band playing in the town square, the audience in comfy Muskoka chairs) to find T by Daniel, where we all partook in a cuppa and took a selfie of our crew.

And then we broke for lunch! There were several options right there in the venue (which was fantastic, by the way, as was the organization of the event and how completely wonderful it was to be there) and we ended up having wraps and salads. After that was a browse in the pop-up bookstore, which was being put on by Orangeville’s Booklore. And then we needed tea, of course, so we went exploring historic downtown Brampton (including a band playing in the town square, the audience in comfy Muskoka chairs) to find T by Daniel, where we all partook in a cuppa and took a selfie of our crew.

Which meant that we were late again for the next panel, Defying Boundaries, with Vivek Shraya, Chase Joynt, and Zoe Whittall. When we finally sauntered in, Shraya was discussing faith and queerness. Joynt began explaining that transness was not just about gender, but about the experience of finding kinship with wider communities. Both writers were asked about defying boundaries as mutual-media artists, and Shraya answers that while her foundation in music sometimes makes her feel like a fraud as a writer, that each form informs the others. Every form is limited, said Joynt, and it’s useful to be able to go beyond those limits.

Which meant that we were late again for the next panel, Defying Boundaries, with Vivek Shraya, Chase Joynt, and Zoe Whittall. When we finally sauntered in, Shraya was discussing faith and queerness. Joynt began explaining that transness was not just about gender, but about the experience of finding kinship with wider communities. Both writers were asked about defying boundaries as mutual-media artists, and Shraya answers that while her foundation in music sometimes makes her feel like a fraud as a writer, that each form informs the others. Every form is limited, said Joynt, and it’s useful to be able to go beyond those limits.

Both artists are also prolific collaborators. “Stories are more powerful with more voices involved,” explained Joynt, and Shraya noted the benefits of getting different perspectives on a project and learning to work with others. They’d been talking about this in regards to different approaches to social media. And Shraya remarked that for her, coming from a self-published, indie background, social media and self-promotion had never been a choice, which made it frustrating to have to listen to older authors complaining about this part of the job. She talked about the selfie as a political strategy for queer people of colour—what a radical act it was to take up space like that. She talked about moving from self-publishing to traditional publishing, and how while there are benefits (getting your books into bookstores being one), there’s still a lot of work required on the part of the artist. Joynt spoke about moving away from academic writing, and the freedom in that, and also about how he’s inspired by artists like Claudia Rankine and Maggie Nelson and their experimental citation strategies.

Joynt talked about his intent upon destabilization of trans narrative, and Shraya concurred: “If I’m going to transmit a narrative of femininity, it’s going to have hair.” When asked about her new book about racism, Shraya noted she was conscious of the privilege inherent in her experience in terms of anti-Black racism and First Nations racism, and she had to think about how to articulate her own complicity.

An audience member asked a question about trans narratives, and the prevalence of depressing themes, and Joynt expressed interest in the question of who gets to be fun. How do we account for the devastating impact of transphobia and give people room to be fun?

Joynt talked about memoir and the construction of story, and how his mom factored into it differently than other characters because she was the one stable force—his mom was always going to be his mom—and so he needed her permission to share her experience. Although Shraya’s take on this idea was very different—she hadn’t asked her mother about including her in the recent project, Trisha because she was going to do it anyway, so this way she didn’t have to go to the trouble of having her mother refuse her. And this all made me think about whether that kind of freedom goes both ways, and what kind of obligation a mother has to her child in regards to making art and telling stories. And was just one of the many additional questions that this fascinating panel led to.

And then finally it was time for Publishing (More) Diverse Stories, with Anita Chong from Penguin Random House, Barbara Howson from House of Anansi, Bianca Spence from the Ontario Media Development Corporation, Rachel Thompson from ROOM Magazine, and Susan Travis from Scholastic Canada, moderated by the amazing Léonicka Valcius who’s even more fantastic in person than you’d expect (which is saying something). Truly a knockout panel, all of them, and I’d really been looking forward to this.

And then finally it was time for Publishing (More) Diverse Stories, with Anita Chong from Penguin Random House, Barbara Howson from House of Anansi, Bianca Spence from the Ontario Media Development Corporation, Rachel Thompson from ROOM Magazine, and Susan Travis from Scholastic Canada, moderated by the amazing Léonicka Valcius who’s even more fantastic in person than you’d expect (which is saying something). Truly a knockout panel, all of them, and I’d really been looking forward to this.

Chong responded to the first question, about her ideal diverse book publishing ecosystem, by explaining that we need a wider pool of readers. There is the typical reader (40-60, white, woman) but she’s not everyone. Those in publishing need a greater understanding of who readers are, and to that end, there needs to be a wider talent pool throughout the entire industry—not just writers or at the publisher level either.

Howson took on the question then of how to widen that readership, and the answer is to publish different voices to include new perspectives, younger people. She noted how difficult it is for people outside of a select socio-economic level to enter the industry, and would like to make it easier for them to do so.

Travis, who works in sales, spoke about broadening the variety of what she has to offer buyers (who are booksellers). Diverse has to mean substance—it’s not just about giving a kid in a picture book brown skin. She explained that buyers are cautious, that they tend to be old-guard, and that perhaps their caution is understandable given the realities of their industry. The people they’ve got working on the floor though, actually hand-selling the books, are more open-minded, and they’re the people that Travis approaches.

How to widen the pool then? Thompson spoke about her experiences at ROOM magazine, and efforts to transform their volunteer editorial board to reflect a more diverse make-up. She noted that an ideal landscape in terms of diversity would mean a magazine like ROOM (with a feminist mandate, publishing women) would not need to exist.

Spence reflected on the nature of arts funding, as well as the costs of getting into publishing via college or university publishing programs and/or internships, and wondered what would happen to the landscape and what kind of new perspectives might be discovered if these elite, expensive experiences were no longer regarded as pre-requisites for publishing careers.

Chong said that she’s so tired of being the only non-white person in the room, and that she continues to insist that inclusiveness doesn’t mean a lowering of standards. Widening the pool only means that you’re going to get something new. She spoke of her experience with the Journey Prize, and how she continually asks herself how she can run this program better. It’s about challenging your own expectations. For her, a solution was ensuring a diverse jury for the prize, and the results have only made the program stronger.

Howson talked about Groundwood Books, which has always had a diverse mandate, perhaps because its founder came from Guatemala and so brought with her another language and a different kind of point of view. And Groundwood has been publishing Spanish books and books from other cultures for years, which made the recent #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement a bit annoying from their perspectives in that they were being overlooked. And so to find a way to say, “Hey! We’re here!” they created a catalogue highlighting those diverse titles. Similarly, House of Anansi created Anansi International, looking for voices from around the world, and has a list of French Canadian titles.

It’s a question of finding and highlighting diverse voices, and working with marketers and the gatekeepers in stores to make it all happen.

Travis sees this as her job, keeping the conversations going, not just having diverse titles ghettoized, but having them integrated into stock. And making sure that conversation gets to the people who are actually selling the books, who are not necessarily store owners.

Spence says that as she is often the only person of colour in the room, she sees it as her job to ask tough questions to make people think about who gets included and why. She also likes to make connections with people just coming up in the industry and serving as an example, make connections and taking on mentorship roles. She encourages others in publishing to make their own connections with people of colour, to diversify networks and communities that way.

Thompson talked about the politics and diplomacy required in transforming communities. At ROOM, their focus was bringing in new people, a new diverse team. An example since then has been their Women of Colour issue, which was hugely successful—their call for submission went viral, and the issue entirely sold out. She’s hoping that their peers in the industry will undertake similar initiatives—they have had such success, but is left wondering why everybody else is so far behind.

Chong said that it all comes down to economics, and who can afford to be in the industry. There is one thing that we can all do though, which is to BUY THE BOOKS. Going to the library is not good enough. There is data about what sells, and if it sells, that data is irrefutable.

Spence said too that we have to make room for more diverse books. How come there can be twelve books about young white women working in the city, but only one Guatemalan book? To which Chong chimed in with annoyance at the way that diverse books are only read at certain times of year, like Black History Month, or Chinese New Year.

Howson noted though that even those who can’t afford to buy books can make a difference by using the library—ordering the books, putting on holds. The library is another place where the reader can demand diverse books.

Valcius added that it’s not all about data and economics though, and she is wary of the idea that it all comes down to the buyers and their agency. Because there are some books that don’t sell, but they still need to be published. Buying books is important, but it’s not all a numbers game.

“We publish poetry,” said Howson. “It’s not a numbers game.” But it’s still important to get a wide audience, to get the numbers up. And also to get books into schools. (Travis gave the example of BC schools’ changing curriculum and new demand for First Nations stories.)

Spence pointed out that writers need to be able to make money. That media outlets need to cover more books, and that shrinking coverage just means that everyone is reading the same 12 books. We need more diverse coverage of books. And that publishing salaries are pitifully low.

Writers these days need full-time jobs, says Chong, fearing for a point at which the only people who can afford to be writers are middle-class.

Thompson explains that ROOM has strategy for diversity now, and that everything they do is measured by it now. And funders are now asking for this to be part of programs, so it’s working for them, and enabling them to pay more people to work for the magazine, which widens their talent pool. They also have found themselves with increasing numbers of subscribers.

The panel took questions from the audience, many of whom were writers who felt the doors were closed to them. This idea was refuted by Chong, who noted how important it is for her to see diverse stories embraced for their universality, to see marginal stories brought into the centre. “There is a hunger for new voices,” she said. What these writers may be perceiving as a weakness isn’t necessarily so.

Spence brought up Shakespeare, and how readers are taught to push through the difficulty in accessing his work. Those picking up books by diverse writers need to be similarly encouraged to get past perceived difficulties such as dialect and find the universal.

“And talk about the universal,” said Howson. “That’s how you sell it.”

Valcius finished things up by suggesting it might help too to keep a sign hanging on the gate, one that says, “Hey, we’re open!”

AND SO. It was everything I hoped for and more. Panelists Nawaz, Dimaline and Joynt sold their books to me by virtue of their stellar presentations. I bought others I’ve been looking forward to reading. I came away inspired and full of questions and ideas, and I’m not the only one. Kudos for Jael Richardson and Léonicka Valcius, two incredible women, for making it all happen, with the help of their fantastic team and their great volunteers. And what I’ve written here only represents one day of three days of programming, not to mention the other panels, workshops and events that were taking place on Saturday while we were there.

So yes, this was a big deal. Hopefully the start of something bigger.

“So often on a panel I am the token. It’s exciting how much more nuanced the conversation is when there are many diverse voices,” tweeted Vivek Shraya after the fact, and it’s so entirely true. The difference for those of us who were there was entirely palpable.

May 9, 2016

Books are not going away

“Books are not going away any more than family is going away, any more than community is going away, anymore than love and intellectual inquiry are ever going away. Poetry is never going away—and yes, it’s important to keep these two ideas in your head at the same time: 1) hardly anyone reads poetry and 2) poetry has always existed.”

“Books are not going away any more than family is going away, any more than community is going away, anymore than love and intellectual inquiry are ever going away. Poetry is never going away—and yes, it’s important to keep these two ideas in your head at the same time: 1) hardly anyone reads poetry and 2) poetry has always existed.”

—Lynn Coady, Who Needs Books?

May 8, 2016

On Mother’s Day

Sunday morning, and I am reclining on the spine of a very, very good weekend, late Friday night aside. I can’t tell you about Friday night because I am a mother who makes a point of keeping my children’s dignity intact, but my goodness, what a story I could tell you over a nice cup of tea. Motherhood is lousy with unsavoury, monstrous things, when it’s not blinding with moments of pure, shining light. But we’re thirty six hours after that now. I spent yesterday in Brampton at The Fold Festival, with three wonderful friends keeping me company on the road and throughout. The day was inspiring and terrific, and I can’t wait to tell you all about it. I arrived home last night to dinner on the table, and a happy rest-of family who’d spent their own very good day together.

And now today is Mother’s Day, and I find myself appreciating my own mother even more than usual for how she saved our family when I was ill last December and cared for my children for a week this winter so my husband and I could celebrate our tenth anniversary in tropical climes. Where would any of us be without her? Certainly never, ever in Barbados. But as my mother is across the country today with her other favourite daughter and other favourite grandchildren, I get to be the star of my own show. Which means breakfast in bed and reading so many papers that my thumbs turned black. Iris gave me a flower she’d planted at playschool, and Harriet gave me a painting she’d made of irises, so floral is the theme. And Stuart gave me a book and a teacup, so he knows me well too. And what I want for the rest of the day is to make soup for lunch (I have become addicted to my immersion blender), to spend some time cleaning up the leaves and seasonal detritus from our backyard, and a little bit of hammock time. Followed by dinner at my favourite restaurant.

This morning I was brushing my teeth and perusing the row of books lined up beside my bathroom sink, and figured it was a good day for a flip through White Ink: Poems on Mothers and Motherhood, edited by Rishma Dunlop, who died a few weeks ago—Priscila Uppal’s eulogy for her friend is extraordinarily good. And I came to the poem “On Mother’s Day,” by Grace Paley, which is tangled, beautiful, sad and very funny, just like motherhood, just like life is. And I am so glad I did…

Suddenly before my eyes twenty-two transvestitesin joyous parade stuffed pillows undertheir lovely gownsand entered a restaurantunder a sign which said All Pregnant Mothers FreeI watched them place napkins over their belliesand accept coffee and zabaglioneI am especially open to sadness and hilaritysince my father died as a childone week ago in this his ninetieth year

May 6, 2016

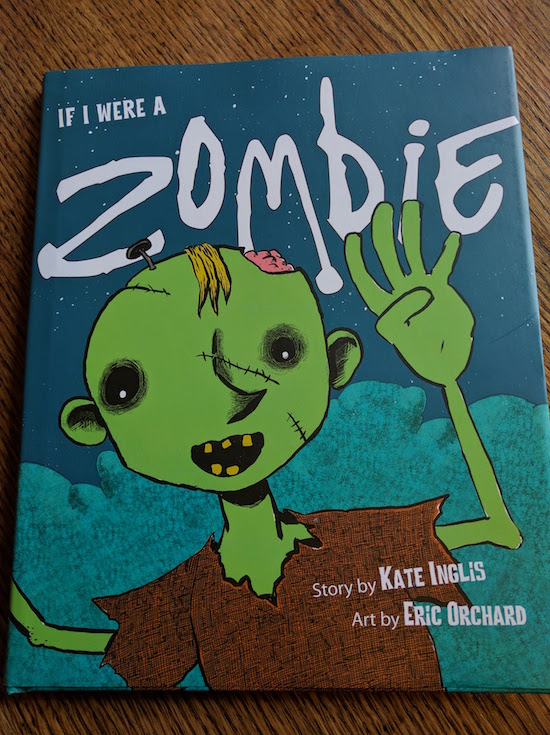

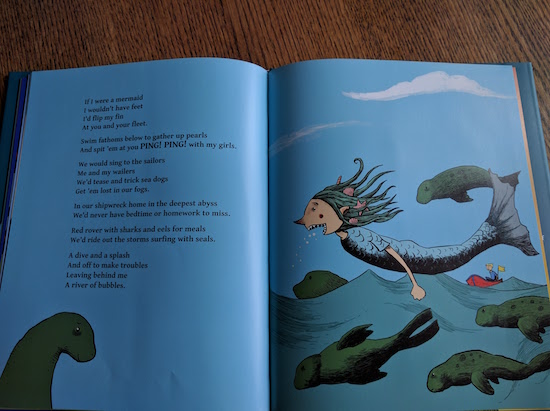

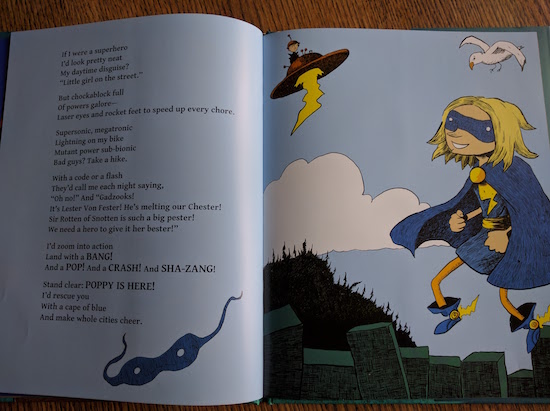

If I Were a Zombie, by Kate Inglis and Eric Orchard

True confession: I don’t really get zombies. Along with “Talk Like a Pirate Day” and Nutella, zombies are a wildly popular phenomena whose appeal I just don’t understand. (I also have no strong feelings about Prince or Shakespeare, which made last week kind of strange.) What I do like is a beautiful picture book though, a kid-friendly one that my children delight in as much as I do, and so to that end, the undead notwithstanding, Kate Inglis’ latest book, If I Were A Zombie, illustrated by Eric Orchard, totally delivers.

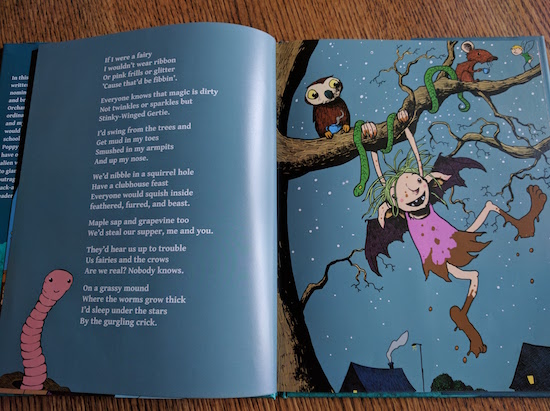

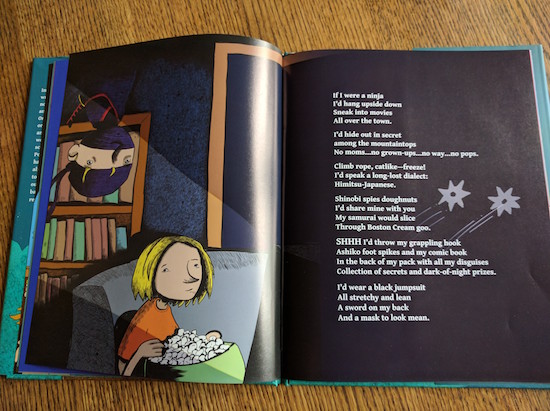

The premise is this: the narrator explores the various possibilities for selfhood amidst the kinds of creatures with children tend to be most fascinated: fairies, giants, witches, pirates and vampires. And even actual ninjas! Plus the zombies, of course.

The text is poetry, whose structure reminds me of Sleeping Dragons All Around, by Sheree Fitch (which is by the same publisher). Admittedly, rhyming couplets would have made for an easier read—sometimes the prose is tricky to say, and it’s hard to keep a rhythm—but I am not sure that such bounciness was ever Inglis’s intention. This is also a book that older children will read on their own which makes matters of rhythm irrelevant. And read it, they will. This is a book with zombies and ninjas after all. But there is more to it than that—this is a book about exploring all kinds of being, about possibilities, and adventure, and dreaming up stories for our lives. Teachers and other grown-ups will easily be able to encourage young readers to explore all kinds of “If I were….”s of their own, after trying out the various roles suggested in the book.

My very favourite thing about If I Were a Zombie though is its treatment of gender, assuming boys and girls alike as its readership—and also that all possibilities in the story are open to both of them as well. For a boy to have fairies and mermaids in his story—and I love Orchard’s non-cutesy takes on these. For children to read a book in which the superhero is a girl, which is particularly appealing to my superhero-loving daughter too. I love how gender becomes completely irrelevant, and all possibilities are open to either.

PS: If I Were a Zombie makes a very cool companion to Vikki VanSickle’s If I Had a Gryphon, but concerned with monsters and imagined creatures, as well as the conditional tense.