July 15, 2016

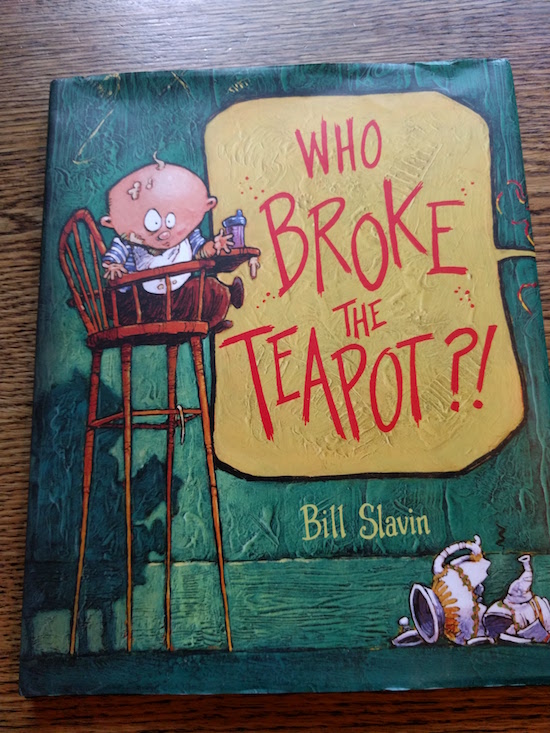

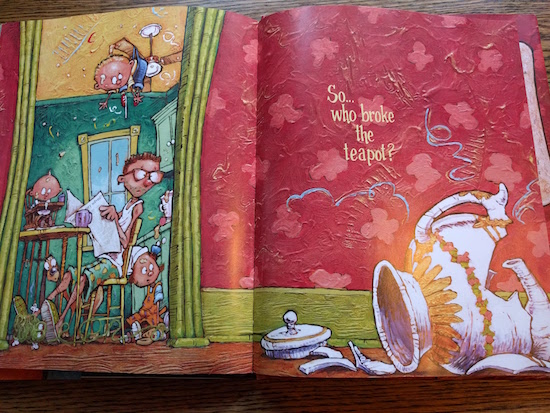

Who Broke The Teapot?, by Bill Slavin

To those who might wonder how a broken teapot could sustain narrative enough to fill an entire book, I will raise the matter of my polka-dotted teapot which got smashed last year on Christmas Day and had me sulking right up until New Years. And so when I heard about Bill Slavin’s new picture book, Who Broke the Teapot?, I did wonder if the plot had been stolen from my life.

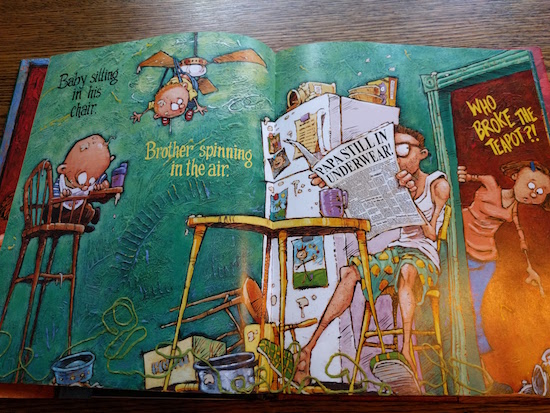

Mother’s beloved teapot is toppled and smashed, and it’s not immediately clear who committed the crime. In our house it was Papa who did it, and he was actually wearing pants, but still, he ‘fessed up right away. Circumstances in Slavin’s book, however, are far more mysterious. The teapot is smashed and the house is in chaos, and what actually happened is hard to discern. And so the set-up of the story is picture book whodunnit. It’s up to the reader to put the pieces together and discover what actually occurred.

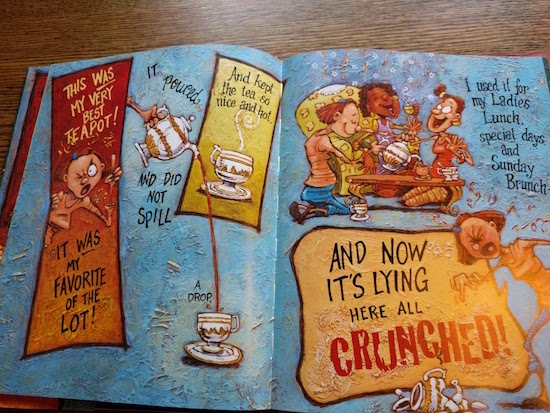

And my sympathies were indeed with the mother, even in her unattractive irateness. I’ve been there, so I totally get it, but even if you haven’t, you can understand what it would feel like to lose your very favourite teapot, your favourite of the lot. Which poured but did not spill a drop. And certainly, such teapots are rare and precious objects, the sort you encounter a handful of times in the span of a life. To find one in pieces on the floor would be devastating.

Of course, I like the book because it is basically a memoir about my life, and I identify with the protagonist, and it is hugely affirming to see my experiences represented in literature. But is that enough to sustain narrative enough to fill an entire book? Is it possible to love this book if you are not a 37 year old teapot enthusiast who weathered a similar tragedy just mere months ago?

And the answer is: YES. My children love this book, and not just because it mentions underwear (although they do love that part—as well as the part where the baby says, “Babadoo.”) Three-year-old Iris can now recite the book in its entirety, and it’s only lived in our house for a week, so it’s safe to say it’s made an impression. The rhyming text is fun and playful, the illustrations are full of action and detail, and the surprise ending is spot-on. And also just a tiny bit ambiguous, which means you get to go back to the beginning and read it again.

July 13, 2016

To Sarah Brick, with gratitude

I’m having a ridiculous amount of fun going through the copy-edits for Mitzi Bytes, which came back to me last week. The feedback is incredible, so insightful, detailed, and nobody has ever read this book so well or carefully before. Sometimes it’s a little mortifying to have it all laid out, just how much you’ve got wrong—but then the gratitude that there’s someone who’s catching all that. But for me there is also the pleasure of reading the book all over again, and reading it at this point in the editorial process, which is the closest I’ll ever come to reading it as a reader instead of its writer. And doing so is reminding me of where it all came from, the little seeds that were planted.

In the years between my daughters’ births, I wrote 40,000 words of a novel, which I don’t think I ever finished. It was a novel about a family in a moment of crisis, each chapter from a different family member. One chapter was “If Life Gave Me Lemons,” which was the only bit that was ever published, and that chapter was very different and disconnected from the rest of the book. Mostly. Except for the part where my character comments that she’s been leaving anonymous mean-spirited emails on her cousin’s mommyblog. That cousin was a sister in the story’s central family, and an unhappy new mother. She was kind of autobiographical, which made the comment that “she was too mean-spirited to be sympathetic” a little insulting when it came back accompanying a rejection I’d received upon sending a chapter to a literary magazine. The novel itself was lacking focus, which is part of the reason I never finished it. Skimming through it the other day, I realized it wasn’t altogether terrible—but then I would appreciate it if we bothered to ask a bit more than that from our books.

The idea of the anonymous blog commenter stayed with me though, even after the novel was abandoned. I thought about it a lot, and this idea morphed into the premise for Mitzi Bytes: forthright blogger begins to question her project and fear for her sanity once she discovers a reader with nefarious intentions. My protagonist, Sarah Lundy, doesn’t share so many qualities with the character she was born from, although they do share a name. I didn’t realize this until I was looking through the old story the other night. It turns out that I am really a bit crap a naming characters, which I am trying to get better at. Reading Duana Taha’s book made me realize that a character with an interesting name inherently has something interesting about her because hers is the name she lives with, and so in the project I am currently working on, I have made an effort to name my characters with more originality. I.e. not call them all Sarah, I mean, although I didn’t even name Sarah from Mitzi Bytes—my daughter Harriet did. This was back when she also named everything Sarah, and in fact had a whole fleet of imaginary dogs called just that. So that’s just how bad my character naming is.

I like that they share a name though, Sarah Lundy and Sarah Brick from the old book. Even accidentally. And I am grateful too to Sarah Brick and her overt unsympatheticness and her hastily sketched, poorly drawn lines, and the failed literary project that she was a part of. Because Sarah Brick proof that nothing is ever really a waste of time. That even if work doesn’t get us to the finish line, it can also be useful in getting us to the place where we can finally begin.

July 10, 2016

Congratulations on Everything, by Nathan Whitlock

While my career in the service industry wasn’t so long, it was longer than it should have been. I worked at McDonalds throughout high school, regularly screwing up my orders, serving Bacon and Egg McMuffins to people who didn’t eat pork, and finally receiving an Employee of the Month award after three years because everyone felt bad for me that it had been so long. I used to hide in the walk-in fridge and scarf down McNuggets and contraband filet-o-fish. I don’t know why I thought that waitressing would be any better than that, but it really wasn’t. At that job, I used to hide in a closet and eat beer-nuts. My career highlight was the night I received a bill and under TIP the customer had written, “No Way!” After that summer I got a job in a library, and never had to carry another tray ever again.

While my career in the service industry wasn’t so long, it was longer than it should have been. I worked at McDonalds throughout high school, regularly screwing up my orders, serving Bacon and Egg McMuffins to people who didn’t eat pork, and finally receiving an Employee of the Month award after three years because everyone felt bad for me that it had been so long. I used to hide in the walk-in fridge and scarf down McNuggets and contraband filet-o-fish. I don’t know why I thought that waitressing would be any better than that, but it really wasn’t. At that job, I used to hide in a closet and eat beer-nuts. My career highlight was the night I received a bill and under TIP the customer had written, “No Way!” After that summer I got a job in a library, and never had to carry another tray ever again.

I kind of loved it though. I was a terrible waitress, but I loved the atmosphere. There was a guy who played guitar on our patio, and I used to play songs in between his sets. One night I was tasked with serving a Z-list (ridiculous) Canadian rock band and their lead singer was dressed head-to-toe in leather even though it was 35 degrees. The other girls I worked with were ridiculously fun, and we used to go out after our bar had closed to come home at 4 in the morning. And between them and the customers, there were so many people, so many stories, conversations that verged in hysteria even if some of them were only in the recounting. Even when things were boring, we were all thoroughly entertained.

Nathan Whitlock’s second novel, Congratulations on Everything, taps into that spirit, and also the soundtrack, which essentially includes Kim Mitchell’s “Go For a Soda.” The scene is The Ice Shack, a local bar in a strip mall with a patio overlooking a ravine—and that its proprietor, Jeremy, is out hacking away at the shrubbery with a machete early in the novel is a suggestion that things at this feel-good local joint (where everybody knows your name) are going to take a violent turn for the worse. In fact we’re told as much, that this novel will be the story of Jeremy’s downfall, and of the Ice Shack’s too. This is the story of a downward spiral.

Jeremy is a good guy with good intentions, and he tries to do the right thing. He tries to play the game. The point of the book though is that the game is rigged and the stakes for business owners are high and terrible. Things aren’t always so bad—the bar is doing okay, Jeremy’s got a solid staff, and the place is something he’s proud of. He’s close to the edge though, and in order to sustain the business, he’s got to get investors on board, and these turn out to be his parents. But then his brother-in-law comes into money, and Jeremy figures he might be interested in supporting his venture. Which is where things get a little slippery, and it’s at this point when he makes a tactical error and sleeps with his waitress, Charlene, who has her own complicated story of an unhappy marriage and general dissatisfaction. And things are only going to go from worse to worse.

As with any establishment, it’s the characters who make Congratulations on Everything a place worth visiting. Whitlock makes Jeremy and Charlene sympathetic even when they’re at their worst, and their stories are supported by a chorus of memorable and hilarious co-workers, customers, and family members. This is a smart, funny, and thoroughly entertaining read. What Whitlock and Jeremy both seem to recognize is that the point of a bar is that it’s a place in which make things happen, and where poor Jeremy fails at his enterprise, his author succeeds with aplomb.

July 8, 2016

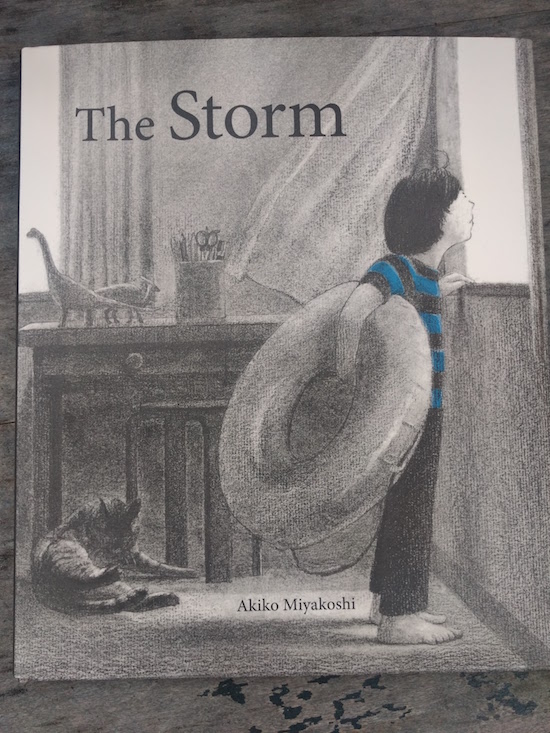

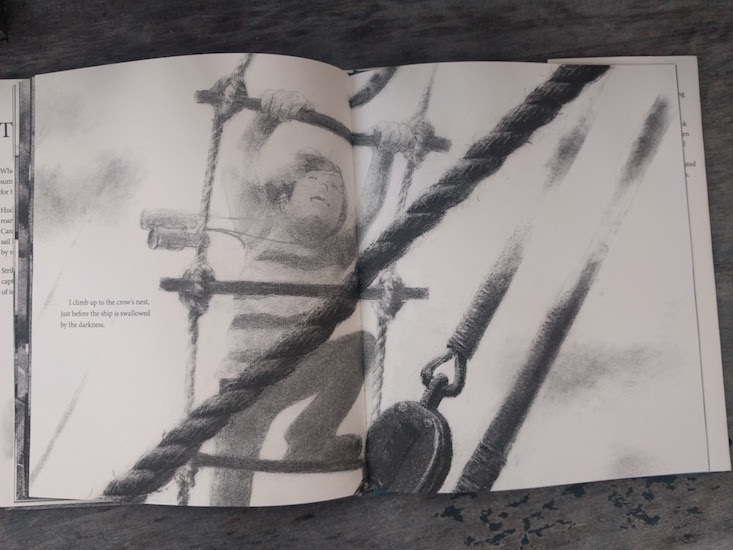

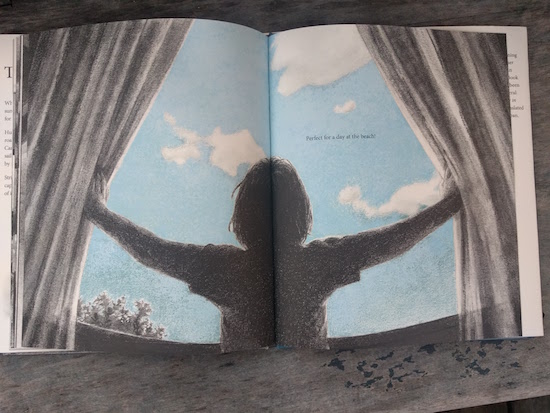

The Storm, by Akiko Miyakoshi

It’s summer, hot and sweltering, not necessarily sultry like the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, but the cicadas are buzzing in the trees outside my house, and it is that certain heightendness to everything that moved me to pick up The Storm, by Akiko Miyakoshi, again. A quiet, simple story, or at least I thought so when I first read it a few months back, when the season outside was only spring. But then yesterday we had a thunderstorm, four days of intense heat broken for a little while with thunder and rain, all that tension in the air. And it was here where I realized that The Storm is not as simple as it initially seems, that the tension is the point, that the story is infused with atmosphere.

The Storm is actually Miyakoshi’s first book, but her second to be translated into English after The Tea Party in the Woods, which gained remarkable acclaim. I haven’t written about that book yet, but I really like it, what with tea parties, forest friends, mismatched slices of pie, and a brave girl with a job to do. The Tea Party is a fairy tale, whereas The Storm just skims the border of one, but both books feature Miyakoshi’s remarkable charcoal illustrations, which mingles abstraction with exquisite detail, and don’t you find that literal shadows add so much depth to a book, a invitation to look closer?

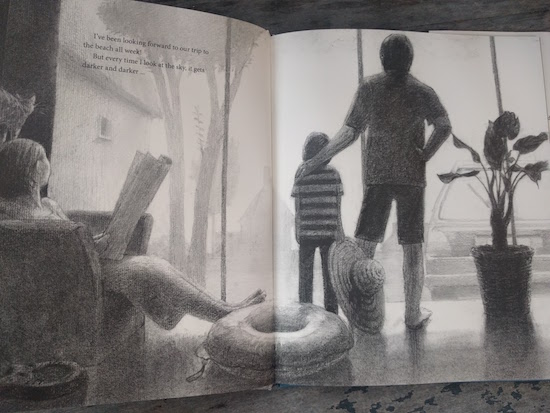

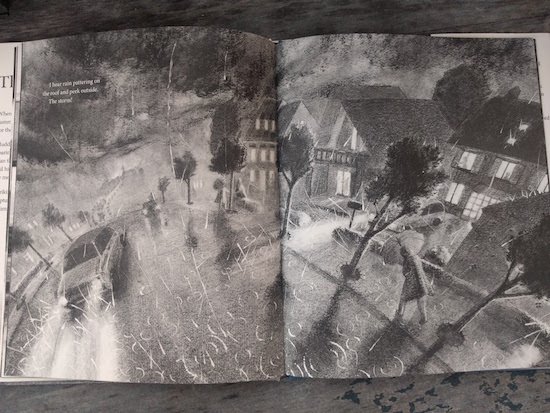

I realized yesterday that The Storm is a perfect summer book, the clash of expectations with reality, extreme weather and flights of imagination. The narrator of the story is looking forward to a trip to the beach the next day, and worried about weather warnings, a darkening sky. The phrase “batten down the hatches” comes to mind, as his parents bring inside their pot plants and secure their shutters, and it brought to mind typhoon season during the time we lived in Japan, those massive storms that shook earthquake-proof buildings that were conditioned to sway in the breeze. They made yesterday’s thunderstorm here in Toronto basically on par with a sun shower.

Afraid of the weather and dismayed by the prospect of his beach day ruined, the boy goes to bed, hides under his covers (presumably his house is air-conditioned. I will not hide under my covers until at least mid-September, and the box fan doesn’t cut it) and spends the night dreaming of controlling a massive airship with propellers that can blow the storm away. Until: “At last, the storm passes, and I sail into clear skies.”

In the morning he awakens to blue skies, and it’s not immediately clear to the reader that the boy was not agent of this miracle after all. Which makes this an excellent story about optimism, the power of imagination, and a reminder that if we just hold on, clear skies will come around again.

July 7, 2016

Head in the Stars

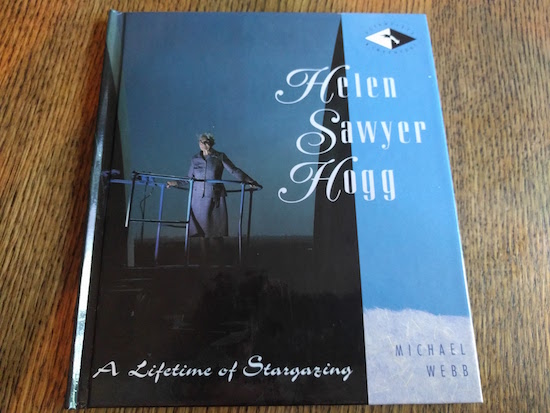

Today UofT Magazine tweeted about scientists who inspire us, which reminded me to finally write this post which has been on my mind for awhile. About a month ago, my daughters got Stargazer Lottie (who was inspired by a space-obsessed six-year-old girl AND has been “the first doll in space”), which came with a “Notable Women in Astronomy” poster. But none of the notable women were Canadian, and it occurred to me that I knew of a very notable Canadian woman in astronomy, who was Dr. Helen Sawyer Hogg. Whose work I only knew, granted, because she’d had a page in my Grade 8 science textbook and my friend and I used to make fun of her name. Which is ridiculously stupid, but the point is that I never forgot her name, and googled her years later and discovered her story was fascinating. (Do textbook writers know the indirect routes that knowledge might take, I wonder? They would probably be surprised.)

Dr. Helen Sawyer Hogg received her doctorate degree in astronomy in 1931, which is remarkable in itself. Her husband was also an astronomer and the two of them would work together until his death in 1951. Although Hogg’s work was not as valued as she was somebody’s wife, and she was often expected to do it without pay. Her first child was born in 1932 and Hogg kept the baby at work beside her in a basket while she studied star clusters at the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, BC. , where her husband was employed as a research assistant. Later that year she received a grant which was exactly enough to pay for a babysitter, and I am fascinated by the idea of how liberating that must have been—and also what it must be to be consumed by cosmic things and have a baby in a basket at once. How does a person reconcile such a vast difference of scale?

Her story would never cease to be cool. After her husband’s death, she took over many of his classes at the University of Toronto, where the family had moved in the mid-1930s. She also assumed ownership of his astronomy column for the Toronto Star, which she wrote for decades (and which was collected into a bestselling book called The Stars Are for Everyone).

There is no full biography of Dr. Hogg. Editions of a science biography for children was published by Michael Webb in the 1980s and 1990s, and while it’s pretty informative, I’m hungry for so much more depth. And so it seems I am going to have to do some of my own digging. Helen Sawyer Hogg’s archives are at the Thomas Fisher Library at UofT, and I think I’m going to have to make some plans to start going through them. In search of what, I am not sure. A creative project? A biographical article? But there is something here, I am sure of it. I look forward to reporting back on just what I might happen to find.

July 5, 2016

Rich and Pretty, by Rumaan Alam

Being white, I have the luxury of not having to think about race very often, and so when I first heard about Rich and Pretty, by Rumaan Alam, what occurred to me was not that this was a brown skinned person writing about white people, but that this was a man who was bothering to write about women. I mean, I know women who are nervous to write about women out of fear of what men might think of them, so it was this that seemed like a tremendous risk to me. But it wasn’t just the novelty—the very first time I read Rumaan Alam at all was in his article in Elle, “Raising Two Boys As Feminists Without a Mother.” Which made clear to me that I wanted to read more of what he’d written, and about women in particular because of the singularity of his viewpoint and its insight. Although Rich and Pretty is the kind of book I’d want to read no matter who had written it, being as fond as I am of well written novels about people making lives in New York during those pivotal moments when futures are still laid out before them.

Being white, I have the luxury of not having to think about race very often, and so when I first heard about Rich and Pretty, by Rumaan Alam, what occurred to me was not that this was a brown skinned person writing about white people, but that this was a man who was bothering to write about women. I mean, I know women who are nervous to write about women out of fear of what men might think of them, so it was this that seemed like a tremendous risk to me. But it wasn’t just the novelty—the very first time I read Rumaan Alam at all was in his article in Elle, “Raising Two Boys As Feminists Without a Mother.” Which made clear to me that I wanted to read more of what he’d written, and about women in particular because of the singularity of his viewpoint and its insight. Although Rich and Pretty is the kind of book I’d want to read no matter who had written it, being as fond as I am of well written novels about people making lives in New York during those pivotal moments when futures are still laid out before them.

It’s Elena Ferrante but light, a novel about female friendship that, just as Ferrante does, acknowledges the spectrum between love and hate that embodies a decades-long relationship between two women. It’s a novel that puts marriage on the sidelines and make friendship its love story, and like any love story, things are complicated. The book begins with Sarah, the rich friend, announcing her engagement, to Dan, who Lauren (“pretty”) thinks is boring, just one of the many things unspoken between them. Sarah, who’s always initiating the get-togethers with Lauren, even though she’s the one who’s so busy. The two friends about thirty, settling into their lives after growing up together, high school and university. Sarah’s career aspirations are vague, but she doesn’t need to bother with that end of things so much, and now she’s getting married. She wishes similar things for her friend, who seems much less interested in being “matched” than Sarah thinks she should be. At one point their lives were very much the same (even with the rich and pretty distinctions) but at some inevitable point their paths diverged, and how does a friendship (a relationship that’s meant to be as peripheral to life itself as it is to the literary canon) navigate the journey of a lifetime? In particular those turbulent, essential years between 20 and 40 when when seems to live at least six lifetimes in a decade or two.

I really loved this book. I loved its humour, its prose, its quietness and detail. I loved its subtle subversions—second abortions and pregnant women with a drink. I loved the difference between the two characters’ voices, how richly the two were delineated, and that the title is tongue-in-cheek—in a Mad Men fashion, Alam’s novel takes the idea of “types” of women and a binary approach to womanhood and complicates the idea entirely to show that women can be whole, flawed, inexplicable and fully realized people whose lives and experiences are worth writing about, thinking about. Which really shouldn’t be such a revelation, and this is still a completely excellent book for those of us who already know.

July 5, 2016

Yesterday was a terrible day

Yesterday was a terrible day, and I didn’t post any photos on Instagram. I don’t know which comes first, the bad day or the no photos. If I didn’t take photos because I wasn’t looking hard enough for things to see, and that is where it all falls apart, And so this morning I took a picture of sunlight falling on a table at the Starbucks at College and Euclid. Although things were shaping up already. Iris and I were meeting my friend Julie while Harriet was at bike camp. And yes, Harriet is at bike camp all week, which sounds ridiculous and first world and all the things that magazine writers like to scoff at parents for, but the fact of the matter is that our attempts to teach Harriet to ride a bike have ended in abject failure and abominable behaviour on my account, and so we’ve decided to outsource, and the sixteen-year-old girl whose very first job EVER is teaching Harriet to ride a bike is doing a stunning, enthusiastic job and hasn’t called her terrible names once, and so we’re already ahead. Except that bike camp isn’t altogether convenient. If Harriet actually knew how to ride her bike, we’d zip along the street and get there in no time, but as things stand, we have to take the bus. With the bike. And Iris. Which is kind of ridiculous, but it’s just for a week and if Harriet learns to ride, it will be altogether worth it. But it also means that Iris and I have to linger about for the mornings and there is not so much to do around there. We went to the library yesterday and it was okay, but by the time we got home for lunch, we were all tired and exhausted and still getting over our weekend away, I think. I put Iris down for her nap, but she refused to go, and I went absolutely ballistic, because the plan this summer is that I write 1000 words a day and Iris isn’t going to nap, how will that ever be possible? I actually wrote the words anyway, after my complete and utter tantrum, which didn’t do anything to improve Iris’s behaviour, never mind the no nap. She continued to be a monster for the remainder of the day, at one point actually finding and getting into actual rat poison (ok, it was mouse poison, but rat poison sounds more dramatic) just to keep things interesting. And then I was threatening to feed her rat poison, and Harriet who was overtired didn’t think that was funny and became hysterical, and it was just terrible, terrible from every angle. When the children went to bed, I was so so relieved. And when I went to bed I slept so well, which made everything seem much better today, as I had a friend to meet and took the photo of sunlight on the table. And then we took Iris to the park where we ran into her friend from playschool who goes to that park every day, which means that for the rest of the week I can take her there and read my book while they play.

The bus-ride home was good, and there was no expectation of Iris napping, so I would not be caught off-guard. I set her and Harriet up with respective movies, there is a tupperware tub in the kitchen full of the kinds of processed package snacks I won’t buy during the school year, and I had a pot of tea brewing. I told them, “Leave me alone for 1000 words.” And they did. And so did I.

And now we’re heading down to the wading pool at the park, which is everybody’s reward.

July 3, 2016

Summer Starts

There is no better way to travel then on trains, where the leg room is ample and there is so much time to read. When we booked this weekend away, the train journey itself was the destination, but we had to arrive somewhere, so we chose Ottawa, where we have best cousin-friends and even other friends, and cousin-friends who were kind enough to offer us a place to stay. And it was Canada Day Weekend, so what better place to be…even if the place we mean to be specifically on Canada Day is our cousin’s beautiful backyard across the river in Gatineau. And it really was amazing.

As we’d hoped, the train journey was a pleasure. I had more time to read than I’ve had in weeks. I finished Rich and Pretty, by Rumaan Alam, which I liked so much and will be writing about, and started Signal to Noise, by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, which was lovely and so much fun. They also had my favourite kind of tea on sale (Sloane Tea’s Heavenly Cream) and so all was right with the world.

It was such a nice weekend—the children had children to play with and I got to spend time with some of my favourite people. We had an excellent time with our cousins, and met up with my dear friends Rebecca who took us to the Museum of Nature, and last night I got to visit with my 49thShelf comrades who I’ve been working so happily with for years but have only ever hung out with a handful of times. Apart from one traumatic episode of carsickness (not mine) and the night the children took turns waking up every twenty minutes, it was a perfect long long weekend. I also learned that it is possible to eat my limit in cheetos and potato chips, which I had never suspected. Also that it is probably inadvisable to start drinking before noon.

We came home today, another good trip, this time with me reading Nathan Whitlock’s Congratulations on Everything, which I am really enjoying, I also started reading the graphic novel of A Wrinkle in Time with Harriet, which we will continue this week. And we arrived home to find that our marigolds have finally bloomed, third generation. We planted them a couple of months back in our community planter, and have been waiting for the flowers to emerge. (Sadly, our lupines didn’t make it.) Summer is finally here proper, what with school out, and even 49thShelf’s Fall Fiction Preview being up (which is my main project for June), and my work days shift with the children being home. I’ve also decided to write a draft of a novel this summer, which is only going to make a tricky situation trickier, but who doesn’t like tricks? We shall see. We will do our best. And there will also be ice cream and holidays and barbecues and sand between our toes, and splash pads and ferry rides and picnics and pools and flowers. It will all go by so fast.

June 28, 2016

White Elephant, by Catherine Cooper

There is a way to get around the problem of writing about white people in Africa, which is by making them abjectly horrible. White people who are coming to Africa in order to “help,” no less, the latest chapter in centuries of colonialism. In Catherine Cooper’s debut novel, White Elephant, the African country is Sierra Leone in the early 1990s, on the cusp of its brutal decade long civil war. Dr. Richard Berringer has arrived to fulfil a long sought dream of working in Africa, helping and healing, along with his wife, Ann, and their son, Torquil. Except that Ann is wretchedly ill, their son is miserable, and Richard is failing to connect with his patients in the way he desires. His attempts to educate them about female genital mutilation and treating illnesses with the local herbalist fall go unregarded, and his views invite hostility from his colleagues who protest that he doesn’t understand the implications of his words and actions. And we see that a failure to work well with others has troubled Richard before, in fact it’s partly what drove him to Sierra Leone, after falling out with another doctor with whom he shared a practice. Not to mention the affair which made him a target of gossip back home in their Nova Scotia community, where he and Ann had been subject to too much attention already thanks to the ostentatious house she’d had built for them and spent so much time and money decorating. Except that once they’d finally moved it, it had been here where her illness had started, something growing in the walls, she thought—mould? The problem driving her mad to the point where she was closing off rooms and/or hacking through the walls, and then news of her husband’s affair had thrown things into a further state of disarray, and it was around this point where they made the move to Sierra Leone—isn’t it amazing that these people would think they’re in a position to help anybody?

There is a way to get around the problem of writing about white people in Africa, which is by making them abjectly horrible. White people who are coming to Africa in order to “help,” no less, the latest chapter in centuries of colonialism. In Catherine Cooper’s debut novel, White Elephant, the African country is Sierra Leone in the early 1990s, on the cusp of its brutal decade long civil war. Dr. Richard Berringer has arrived to fulfil a long sought dream of working in Africa, helping and healing, along with his wife, Ann, and their son, Torquil. Except that Ann is wretchedly ill, their son is miserable, and Richard is failing to connect with his patients in the way he desires. His attempts to educate them about female genital mutilation and treating illnesses with the local herbalist fall go unregarded, and his views invite hostility from his colleagues who protest that he doesn’t understand the implications of his words and actions. And we see that a failure to work well with others has troubled Richard before, in fact it’s partly what drove him to Sierra Leone, after falling out with another doctor with whom he shared a practice. Not to mention the affair which made him a target of gossip back home in their Nova Scotia community, where he and Ann had been subject to too much attention already thanks to the ostentatious house she’d had built for them and spent so much time and money decorating. Except that once they’d finally moved it, it had been here where her illness had started, something growing in the walls, she thought—mould? The problem driving her mad to the point where she was closing off rooms and/or hacking through the walls, and then news of her husband’s affair had thrown things into a further state of disarray, and it was around this point where they made the move to Sierra Leone—isn’t it amazing that these people would think they’re in a position to help anybody?

The story is told in chapters moving between the three members of the Berringer family, each of whom is perfectly terrible in his or her own way, eternally casting themselves as victims of their tale. Each of these people is also very hard to like, to sympathize with, Cooper making clear that these aren’t meant to stand for ordinary people but are each their own personal brand of awful. Solipsistic, oblivious to how they are perceived by others and of their effect on the world around them, short-sighted, cruel and mean. On one hand, all of this can get to be a bit much—Ann and Richard are so loathsome it’s a bit hard to fathom how they ever even liked each other once upon a time. But on a symbolic level, it’s perfectly apt, and attests to the inherent self-interest of white people turning up in Africa ever since white people started turning up anywhere.

The story is a little bit too long—there is so much action in the present day as the story moves toward its climax, and then all the details of the past are all drawn out in flashbacks, and it takes a little while for momentum to build. But once it begins, the story is quite gripping, these terrible people hurtling toward their inevitable disaster. The consequences of Torquil’s usual troublemaking have higher stakes in an area that is slowly becoming a war zone, soldiers patrolling checkpoints nearby, plus Ann finds her place about zealous missionaries and decides adopting an orphan would make her into the kind of person she wants to be, and Richard’s determination to provide medical care to a girl who’s been accused to witchcraft has results far beyond what he’s expected. Against all this drama, the three are grappling with more ordinary questions about love and family and marriage and home—and then there’s those threatening letters from Canadian Revenue. The only thing sure (although none of them see it) is that the end isn’t going to be pretty.

June 28, 2016

Book Publishing: The Long View

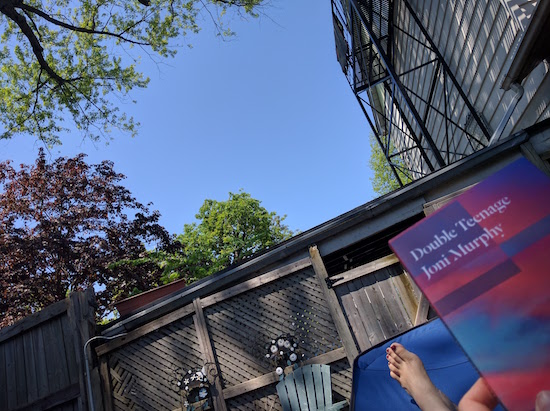

Yesterday I responded to a tweet by Joni Murphy (remember Joni Murphy? She wrote the wonderful novel Double Teenage that I devoured last month) about the ridiculously small window of books coverage in the mainstream media. She’s absolutely right—once the “new release” glow fades, so does a lot of interest…but I suggested that this doesn’t matter. I mean, yes, it would be altogether excellent to find oneself on a bestseller list the week one’s book was published, and for the momentum to be undeniable and inexhaustible, and to have your book be everywhere. Yes, authors do need to work and hustle to get the word out for sure. But here it is: you can only do the best that you can do. And even that is not really guaranteed to get results. And so what an author really needs to do is be satisfied with immediate coverage, but also keep the long view, and have faith in the book and its readers.

For sure, this kind of faith is not the stuff of bestsellerdom, but ultimately it is what really matters. It’s the difference between your book living on someone’s bookshelf for years and years, and being put out on the curb. It means your book not being available en-masse at secondhand bookstores six weeks after the pub date (and hello copies of The Nest and The Girl on the Train. I see you!) It means real people connecting with your work rather than just hearing about it, knowing the cover. The thing about books, good books, see, is that they have long lives, even if it’s hard to measure just how. Although the most excellent thing about the internet is that we do have some kind of a record now, a way of registering reader responses long past the on-sale date. (“The standards we raise and the judgements we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work,” writes Virginia Woolf in her 1925 essay “How Should One Read a Book,” anticipating the literary blogosphere[s]). It would be really wonderful to write a book that set the world on fire, but it’s just as stunning for me as a writer to discover, say, that my book is still being picked up and appreciated over two years after it first was published.

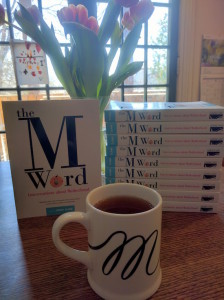

My point proven by two things that happened after my exchange with Murphy: last night I discovered a blog post from last month by the fantastic Red Tent Sisters (who I met when they were at our book launch way back when…) called “Why Is Mothering so Difficult?” It’s a terrific post, but I was even more thrilled by their suggestion that reading a book like The M Word might make mothering a little bit less difficult. They’ve also included The M Word on their Top Fifty Beautiful Books for Soul Sisters, which you can receive if you sign up for their newsletter (and here’s a tip—if you put somebody’s book on a list they receive if they sign up for your newsletter, that somebody will ALWAYS sign up for your newsletter). So I was feeling pretty good about that, and then this morning I was tagged on Instagram by a woman called Leah Noble with a gorgeous photo of The M Word alongside a just-as-delicious-seeming breakfast. Two signs from the universe that the book goes on, after a while of radio silence. Yes, both readers are connected with writers in the book, so I’m not suggesting that the whole thing is made from fairy dust, but there is an element of serendipity about it. You really do have to trust that the book will find its way—and the good books really will. Even if sometimes the ways are small and quiet.

My point proven by two things that happened after my exchange with Murphy: last night I discovered a blog post from last month by the fantastic Red Tent Sisters (who I met when they were at our book launch way back when…) called “Why Is Mothering so Difficult?” It’s a terrific post, but I was even more thrilled by their suggestion that reading a book like The M Word might make mothering a little bit less difficult. They’ve also included The M Word on their Top Fifty Beautiful Books for Soul Sisters, which you can receive if you sign up for their newsletter (and here’s a tip—if you put somebody’s book on a list they receive if they sign up for your newsletter, that somebody will ALWAYS sign up for your newsletter). So I was feeling pretty good about that, and then this morning I was tagged on Instagram by a woman called Leah Noble with a gorgeous photo of The M Word alongside a just-as-delicious-seeming breakfast. Two signs from the universe that the book goes on, after a while of radio silence. Yes, both readers are connected with writers in the book, so I’m not suggesting that the whole thing is made from fairy dust, but there is an element of serendipity about it. You really do have to trust that the book will find its way—and the good books really will. Even if sometimes the ways are small and quiet.

And here’s another thing that I discovered last night, the other side of the publishing coin, eight months before the release date. My novel Mitzi Bytes is now available for pre-order, and unless I have a rabid superfan I am unaware of, my sister purchased the very first copy last night. But this doesn’t mean that it’s too late for you: you can pre-order the book at Chapters Indigo, or from Amazon, or head over to your local proper bookshop to do so.

(But my point is that even if you don’t, it doesn’t fundamentally matter. Life is long and good books are even longer.)