September 11, 2016

Ardent Desires

“Whom does a child belong to? What responsibility does it bear to those who ardently desired—or even designed—it without knowing what ‘it’ was?” —Rachel Cusk, “What She Bears.”

I always wanted to be a mother. It did not seem to be an idea worth examining, or it was worth examining as much as it’s worth examining why I might want to be a creature who walks upright or a being with lung capacity (although when I got pneumonia last winter, it was underlined how tremendously luxurious it is to be a person who breathes). My desire for motherhood was not something I’d been told I should want; it would have been impossible to talk me out of it. I read Rachel Cusk’s seminal book on motherhood, A Life’s Work, before I had a baby, and missed the point of it entirely, so intent was I upon upon my own desire to have a baby of my own, to make my own story. I suppose Cusk had been trying to warn me, even to talk me out of it, but I took no heed. I “ardently desired it” and I didn’t know what “it” was, it was true, but there are some boxes that don’t need to be unpacked. I do think that Rachel Cusk has made it her life’s work to make things far more complicated than they need to be.

Another thing I know is that there are women want to not be mothers as ardently as I wanted to be one. I am in complete understanding of that certainty. Those women and I are on the same wavelength, I’ve always thought. All of us wanting what we want because we’re listening to our own hearts, and not because this is what anyone has told us about how to be a woman.

—Ambivalence, by the way, is not the opposite of certainty. I think many of us manage to live with both. For example, I always wanted to be a mother. And then there was a time after I became one that I didn’t want to be a mother at all.—

It was during the time, after my daughter was born, when I didn’t want to be a mother and wondered how I’d got the whole thing so wrong, that I read Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work again, and finally understood what she writing about. And I was grateful that someone had been willing to write about what my days were like, the boredom, the desperation, the inanity of those people who were imploring you to “enjoy every minute.” That someone was writing about how motherhood was so terribly hard, and lonely. Putting a name to the thing, which was “maternal ambivalence.” Sometimes I hated my baby (usually in the middle of the night when neither of us had slept for hours) and I wondered where my life had gone, and lamented that it was possible that I’d never crawl out of the dark hole that had become my life. I was learning how to love my baby too, but this was more of a work-in-progress.

How long did this go on? The crying-on-the-floor-while-not wearing-clothes period was a few weeks, at most, although it is the salient image for me of all that time. Eventually I learned how to bake scones while holding my baby in one hand, and to breastfeed while holding a book, and there would come a time in which the baby would be a creature woven into the fabric of my life. A different fabric, sure, but it was something I could recognize. I could find my self. I learned that a mother has to insist on the self, and not to feel badly about that. I recall many trying times, but these eventually became more about abject fatigue than existential despair. When my baby was around a year old, I realized that for the most of my days were good ones now. She was getting older, and together we had learned how to make it work.

—It helps too that I became a mother when I was 29, which is relatively young these days, and even more importantly that I was wholly unaccomplished in all the fundamental ways when my child was born. In some ways, getting pregnant had seemed like a concession to life—”All right, I give in,” because there really wasn’t much else going on. And it could have been a concession had things not started to happen to me because of motherhood—creative connections made with women I met through our children, the stories motherhood inspired me to tell, the books it pushed me to read, ideas it drew me to consider, questions I’d never thought to ask before. Motherhood was to be my creative and professional blossoming in ways that were entirely separate from the baby, who was a blossom all her own. All which is to say, everything important I’ve done as a creative person I’ve done since becoming a mother. There may have been a pram in my hall, but that hall was huge and crowded with doorways, and these were rooms that I wouldn’t have been able to access any other way. The situation would be different if my life had been as creatively rich beforehand, if I felt I’d had to give something up in the process of becoming a mother. Truthfully, I’d not had that much to give.—

The book,The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, was inspired by conversations with friends about infertility. Having known without a doubt that I wanted to become a mother, I could empathize with those woman who wanted the same but could not achieve it easily. I understood too how the desire was magnified as “it” seemed less attainable. Its elusiveness makes it all the more coveted, a complex paradox too because as motherhood seems elusive for these women it is also everywhere in our mommy-saturated society (which also doesn’t respect or support actual mothers at all, but that is another story…). There are all kinds of solutions to the problem of infertility, usually delivered by people who like to suppose that these things are simple and/or people who’ve seemingly never wanted anything at all—adoption!, or there are too many people in the world anyway!—and I understand how none of these answers would suffice.

Rachel Cusk though, doesn’t seem to get it. In her recent review of two new books about women’s experiences of infertility, she is frustrated by the very premise of a woman desiring motherhood. She takes particular offence to Julia Leigh’s point in her memoir, Avalanche, that motherhood and the creative life could be compatible. Cusk quotes the following: “The truth was that many women had gone before me and found ways to lead a creative life and also be a mother. There were countless prams in countless hallways. It wasn’t ‘rocket science.’ It wasn’t either/or. There was enough space.” This Cusk takes as a “dismissal” of “the honourable testimony of female literary history of what is very much the rocket science of combining artistic endeavour with family life.” She compares Leigh’s tone to that of the Brexiters, which is kind of of the worst thing you can say about anybody these days, short of calling them ISIS. Leigh, says Cusk, is failing to interrogate a fundamental truth at the outset of her journey into motherhood, and therefore it’s inevitable that she’ll come into danger.

This is a terrific failure of empathy, I think. And also not so surprising considering Cusk’s fierce interrogation of everything, which I appreciate because it has resulted in her substantial body of work, but which I also imagine makes it hard to be a person in the world. I have always felt rather third-wave feminist when it comes to Cusk’s ideas (which is saying something, because I have never feel very third-wave), understanding her ideas on a basic level but finding her tiresome on others. All those questions in her novel, The Bradshaw Variations, in which the woman goes out to work and the husband stays home and supports the family in domestic fashion and this switch causes the family dynamic to fall apart, and this notion that success for a woman, for a feminist woman, is a male-defined one. The right to wear a suit and tie, if not literally. I never wanted that. And the idea that women pursue these ideals and end up unsatisfied seems kind of obvious to me.

I think it’s important that we critique why we make the decisions we make in our lives, to acknowledge the complicity of the patriarchy in the choices we make—whether we marry, change our names when we do, shave our legs, and wear uncomfortable shoes. I think interrogation is important. But I am not sure that the decision to have a baby necessarily falls into this category. We should interrogate it for sure, but for me, no amount of interrogation would have checked my desire to become a mother. Having a baby is not like putting on lipstick. Its more than that. And the desire for it was beyond me. I can’t explain it. I just knew.

And the thing is that Julia Leigh is right about the creative life and motherhood: people make it work. I think of Helen Sawyer Hogg, the Canadian astronomer, cataloguing star clusters during the 1930s while her baby slept in a basket beside her in the observatory. I think of Rebecca Woolf and her recent post, “Hell Yeah you can be both mother and artist.” I think of Alice Munro and Margaret Atwood and Margaret Drabble and Eula Biss and Zadie Smith and so many of my favourite writers whose work is informed by their experiences of motherhood, who don’t necessarily find the pram in the hall something to trip over. (Here’s the thing too: eventually the pram leaves the hall. Children get legs of their own. Read my friend Nathalie’s recent post, “Redundant“.) I wonder what Virginia Woolf could have written if she could have had the child she wanted. And I think of all the brilliance we would have missed out on in Rachel Cusk’s work had she not done her own grappling with all the questions that having a child raises. What would she be writing about now? Would I even know who she was?

So why shouldn’t Julia Leigh have that? Or desire it, at least. What is wrong with that, the unexamined yearning. Cusk so fixated on the origin point of Leigh’s story that the story itself is brushed away, that things go terribly wrong with Leigh’s relationship and with her health, and that work indeed gets in the way of her fertility treatments, and it’s hard to balance both, and it’s as though Cusk is writing, “See? I told you so. Not rocket science, eh? You have no idea.” As though such hardship is the inevitable outcome of the desire for a child, to be a mother. Instead of understanding that infertility is its own particular trajectory, one that is injected with hormones and other tortures, and disappointments and a mix of hope and despair. What could the journey have been, Cusk never seems to wonder, if things had been simpler, if Leigh had received the baby she desired. Plenty of strong relationships have cracked under the pressure of infertility and strong women too. It seems cruel to turn this into a moral tale.

“I just never thought it would be like this, ” is a sentence I wrote in my essay, “Love is a Let-Down” (which basically launched my entire literary career, no exaggeration). I used the line again in an essay four years later, “When Love isn’t a Let-Down After All,” after the birth of my second child, whose early days were so remarkably different from her sister’s, brighter, more salubrious and utterly infused with happiness and well-being. If I’d heard anyone describing new motherhood in such a way beforehand, I would have assumed they were lying, particularly after the darkness of postpartum days with my first baby. “So I think what we have to keep in mind as we’re sharing our stories,” I wrote, “is that stories are stories instead of facts or even destinies…The great thing about stories is that sometimes you get to write your own.”

There are so many ways to be a woman and a mother (and negotiating with infertility complicates both of these).

Which Cusk doesn’t seem to realize. And I think it’s possible she’s has been reading “the honourable testimony of female literary history” too narrowly, doing what we all do in applying our own personal lenses to other people’s stories. What I mean is that women should allowed to want to become mothers without compunction, and that (and I will never cease to be grateful to Cusk and her work for this, for she blazed a trail) when we become mothers—by in-vitro fertilization, even—sometimes we’re allowed to hate it too.

September 9, 2016

And then there were two

And then there were two—kids in school, that is. And now there is one, which is me, home alone for the first time in nearly two months. Not alone for long though—I had a co-op shift at Iris’s school this morning, and so it’s just been for the afternoon. Yesterday Iris and I had a special last-day-before-school day together, and the two days before that we had orientation and cleaning at the playschool (where I mopped under carpets and cleaned out garbage bins—it’s non-stop glamour for me). And so this week has been busy, definitely not regularly scheduled programming, and I’ve had deadlines and have had to work in the evenings to get it all done. But it’s all done now, and next week the new routine begins and…it’s so good I want to swoon. Starting Monday, Iris will be a playschool from 9-3, and so my days will be free to focus on my work (as well as swimming! I’m getting a membership to the UofT pool and am intending to swim every day…) and every evening I don’t have to do anything but read books and go to bed at 11:00. The thought of such things makes me want to start whooping with joy.

I will be doing my freelance work, and will have lots of time to focus on 49thShelf, and other writing projects I’ve been meaning to get to—short stories that need revising, essays I’m intending to write. I have also been writing a novel all summer and would like to finish a draft this fall. And my blogging course starts in a few weeks, so I’ll be freshening up that material. And I know that soon 9-3 won’t seem like time enough, the same way our apartment seemed really spacious when we moved in 8 years ago, but I am going to luxuriate in it for a little while.

PS Check out my baby. When Harriet headed out into the world, I remember thinking, “World, be kind to her.” With Iris, I’m thinking, “World—watch out…”

September 8, 2016

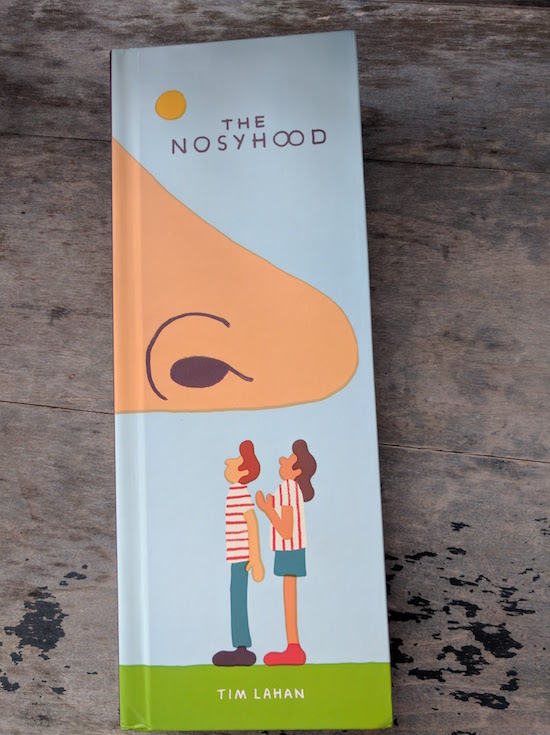

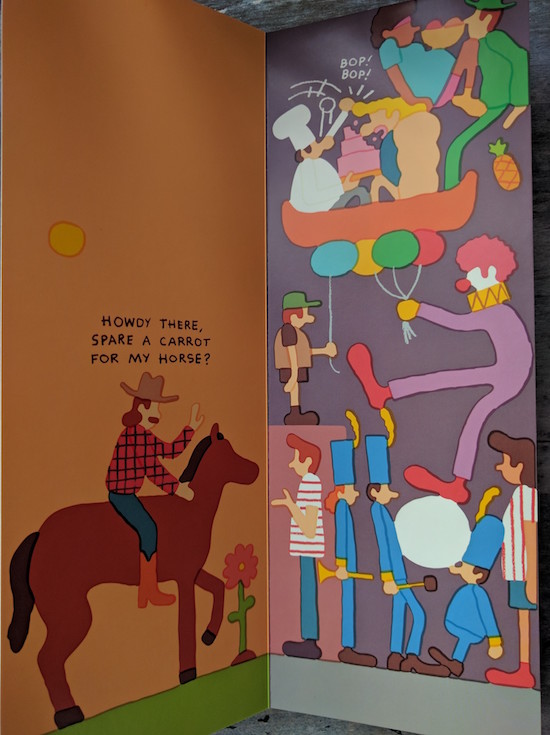

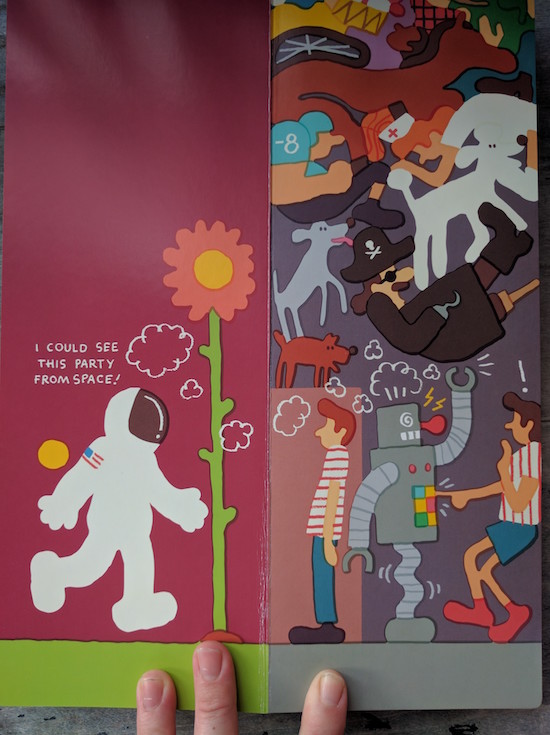

The Nosyhood, by Tim Lahan

Tim Lahan’s first picture book, The Nosyhood, is full of surprises, the first being its size, which is very tall, the book making excellent use of its extraordinary height and being spectacularly conscious of itself as an object (which is very satisfyingly gripped in one’s hands) and the space it has to tell its story.

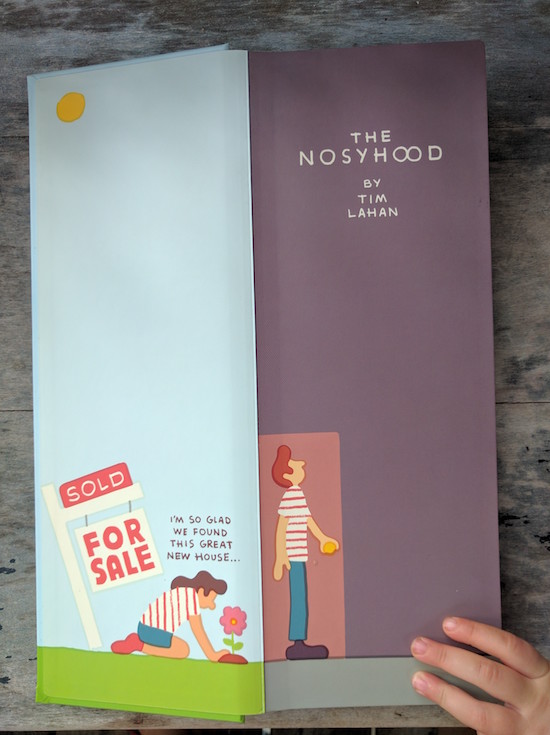

It’s the story of an unassuming young couple who buy a house, the book’s centre functioning as their home’s threshold. “I’m so glad we found this great new house,” says the Her of the couple, with no idea what their neighbourhood has in store for them.

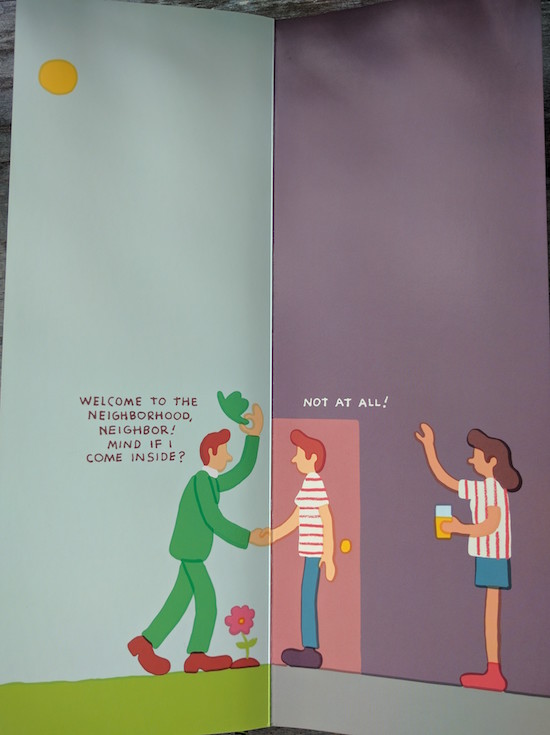

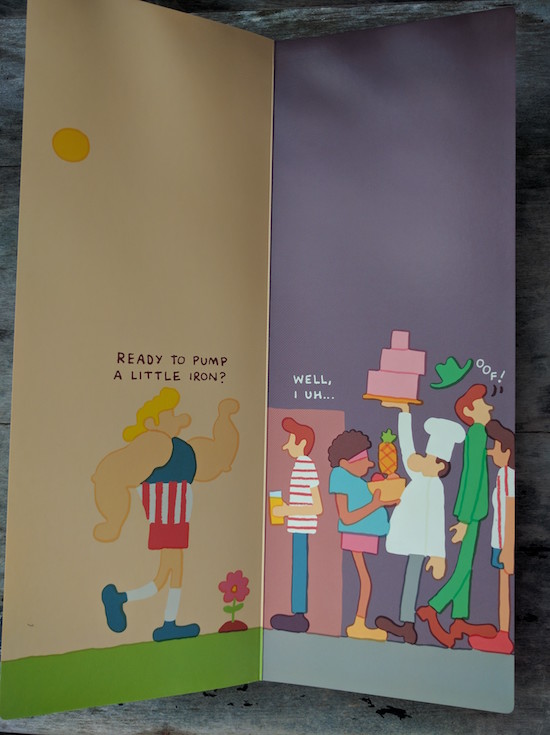

At first it seems pretty positive—a friendly neighbour (in a green suit) stops by to so hello, and they invite him inside. They’re even cool with the woman who shows with with a bowl full of fruit, and the baker with a three-tiered cake (well, wouldn’t you be?) but when Arnold Schwarzenegger shows up (“Ready to pump a little iron?”) things start to get a little weird. And the party inside is beginning to get a little crowded.

There’s the guy with the canoe, and then the clown with the balloons, and pretty soon this very tall book doesn’t seem tall enough. For the most part, Lahan lets his images tell the story, although they’re nicely punctuated with some dialogue by the party-goers.

The brass band might seems like it’s all gone too far, but there’s still time for the guy on a horse (who’s not just looking for a party, but wants a carrot) and it was here where I realized how wonderfully The Nosyhood reminds me of the works of Remy Charlip, books like Mother Mother I Feel Sick and Arm and Arm and I was definitely thinking about Little Old Big Beard and Big Young Little Beard: A Short and Tall Tale.

It gets absurd. There are donuts by bylaw and the basketball player who turns up saying, “You guys are way more fun than the last seven couples who lived here…” There is the astronaut and the robot and a pirate and three dogs, and you get the sense the something’s gotta give. And when it does, it’s a nose that come around and stopped to sniff the flowers, and when that big nose starts sneezing, everyone would be advised to take cover.  “I feel like this might not be the best neighbourhood for us after all,” the He from the couple is saying to Her at the end as they clean up from the disaster. A perfect, hilarious, understated end to this very funny and clever book.

“I feel like this might not be the best neighbourhood for us after all,” the He from the couple is saying to Her at the end as they clean up from the disaster. A perfect, hilarious, understated end to this very funny and clever book.

September 7, 2016

Listen Again

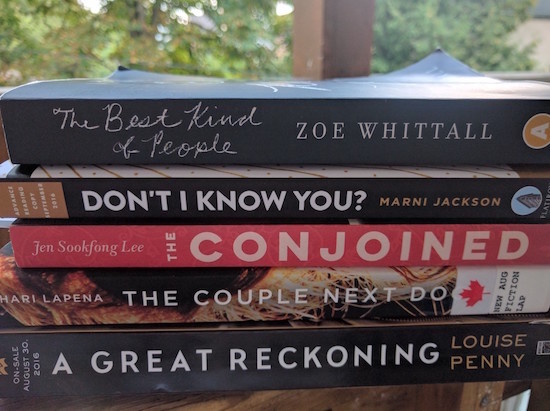

I was so happy to talk books again today on CBC Ontario Morning. If you didn’t catch the broadcast, you can listen again on the podcast. I come on just after 33 minutes, and oh my, did I ever have some great books to tell you about, including Zoe Whittall’s The Best Kind of People, which was just long listed for the Scotiabank Giller Prize.

September 6, 2016

On Reading Grace Paley Wrong

The thing about years, of course, is the way they’re layer upon layer. Today I dropped Harriet off at Grade Two, which is not such a departure from Grade One—same great teacher, same beautiful classroom. And then Iris and I headed down the street, back to playschool, and it occurred to me that it was four years ago today that I first entered the playschool as a member of its community. As I did today, I showed up for my requisite two hours of cleaning to help get our (cooperative) playschool all set for the new school year. It was also the day that Zadie Smith’s NW came out, which I’d had on special order from Book City, but that is neither here nor there. I’d been about five minutes pregnant with Iris at the time, but I didn’t know it for sure—it would be another week or so before my pregnancy would be confirmed.

The thing about years, of course, is the way they’re layer upon layer. Today I dropped Harriet off at Grade Two, which is not such a departure from Grade One—same great teacher, same beautiful classroom. And then Iris and I headed down the street, back to playschool, and it occurred to me that it was four years ago today that I first entered the playschool as a member of its community. As I did today, I showed up for my requisite two hours of cleaning to help get our (cooperative) playschool all set for the new school year. It was also the day that Zadie Smith’s NW came out, which I’d had on special order from Book City, but that is neither here nor there. I’d been about five minutes pregnant with Iris at the time, but I didn’t know it for sure—it would be another week or so before my pregnancy would be confirmed.

It was a strange and vivid year, the year that Harriet was three and I was pregnant with Iris. I’ve written before about all the women I met, those hours we spent in the playground not bothering to take our children home for lunch because the conversation was just too fascinating. I remember taking my shoes off on days when it should have been too cold to be doing such things, but the sunshine had rendered the sand hot and glorious, and I liked to bury my feet in it. I remember that warmth, and those hours, and how conversations seemed to unspool, landing in messy piles all around us.

And then tonight I saw that Sarah was reading “Faith in a Tree,” by Grace Paley, and it occurred to me to get my own Collected Paley off the shelf and read Faith again. And reading it, I realized that probably I’ve been reading the story all wrong all these years. That so besotted was I by the idea of co-workers in the mother trade and those mothers in the park, and all their talk, that I hadn’t really paid much attention to the end of the story: “…Then I met women and men in different lines of work, whose minds were made up and directed out of that sexy playground by my children’s heartfelt brains, I thought more and more and every day about the world.”

I really thought that they’d been it, those mothers in the park. I really had thought she meant that this, the mothers stopping to talk, was the most important conversation. But it wasn’t, her revelation. Faith needs more than that, chatting women lounging in trees. The world needs more than that, at least if we ever expect to do anything about it. Whatever the women in the playground are doing, they’re not thinking more and more and every day about the world.

It doesn’t shock me as much as it might have, to discover that a beloved passage of a story doesn’t mean what I thought it did at all. It is possible that kernel of the truth of the matter had lodged its way into my mind. When I wrote my own post about my co-workers in the mother trade, I remarked on the fleetingness of it all, that those conversations had happened in a moment. A time when I searching for my own moorings as a parent, as a mother, and when the possibilities were still terrifyingly wide-open. I don’t really hang out in playgrounds anymore, not the way I once did, whiling away hours as the sun crossed the sky. There’s always someplace else I’ve got to be, one more thing I’ve got to get to. I suppose you could say I’m thinking more about the world, though it’s not quite so noble as that.

September 5, 2016

Summer Thanks

Dear Summer 2016:

Thank you for being too much. Thank you for being too hot and sweaty, and too exhausting, and too nutty and too intense…and also for not being long enough. And/or for being over at precisely the right moment.

Thank you for train travel, books and tea to pass the time with, and delicious sandwiches packed in wax paper. Thank you for Lake Ontario sweeping by outside the window, our companion for most of the journey. For Napanee for making me think of Avril Lavigne, and Sk8ter Boi. Can I make it any more obvious?

Thank you to friends who received us, let us sleep in your spare rooms and eat cereal from your bowls, and friends who gave us dinner and poured us wine and made us feel so entirely welcome. Thanks to friends who showed us your city and made us fall in love with someplace new.

Thank you to to High Park for always making for a perfect summer day. Thank you for your splash pad, overpriced ice cream cones, your steep grades, and sparkling pond, your chipmunks and geese for delighting and scaring us (respectively).

Thank you to Peterborough for letting us hang out for a few days. Thank you to the Millennium Park for your perilous rock structures that the children liked to leap from.

Thank you for the sunshine and your shady trees, and days beside a lake.

Thank you to the Grandparents who hosted us and their friends who let us swim in your pool (and kayak even!).

Thank you for your rainbows, dear summer. For your silver linings and consolations, your tough lessons and your toughening ones, and for your refusal to let Don*ld Tr*mp and Brexit own you. For being better than all that.

Thank you for the things that grew, even if they weren’t the lupines. Thank you for the lavender and the marigolds, and the cosmos that grow in the street and amaze us with their tenacity.

Thank to the Chihuly exhibit, for being fascinating for all of us. Thank you to the museum for your air conditioning on hot afternoons.

Thank you for the parks, and the picnics, and the piles of people I thoroughly love.

Thank you for the farmer’s market, which becoming deliciously slutty as July turned into August and the peaches got ripe.

Thank you for the summer skies at dusk, every evening a reminder that the world is amazing.

Thank you to Ghostbusters for being ridiculously fun.

Thank you to ferry rides and the Toronto Islands, and wholly perfect days.

Thank you for afternoons passed on the Toronto Riviera.

We’re grateful for wading pools, and for the children for giving me an excuse to hang out in one. Where would I be without them?

Thank you for the picnics in the park, and Denise’s blueberry pie, and the most amazing friends a family could ask for.

Thank you to fire, for letting us make you. Thank you for only raining a little bit on our camping weekend, enabling the weekend to be so totally fun. Midway through the summer and we were still going strong.

Thank you summer for your moody skies, and unforgettable afternoons with friends.

Thanks for the big beach smiles, and one more swim before we hit the road, and so much sand in the car.

Thank you for a week at the cottage, a week that rocked everybody’s world, and left us so relaxed and happy and me only moderately rashy.

We are thankful for big jumps off the dock.

We are so thankful for hammock afternoons, and books that match our outfits (even if the book itself didn’t quite live up to the hype).

Thank you for ice cream from a truck. And ice cream from anywhere, for that matter.

Thank you for perfect refreshment over and over again.

Thank you for your green trees and your cool shade and so many things to climb on along the journey home.

Thank you for silliness with friends, at the board game cafe, and the Science Centre, and in shady backyards, and other memorable points along the way.

Thank you for your magic and your mystery tours, and for the sharks.

Thank you for your street style, your shades, and your cool attitude.

For the sunny days.

And the sparkling nights.

For your green lawns and garden hoses…

and for including all the fixings.

Thank you for your triumphs and glories and deliriously dizzy goodness.

We had a very good time.

Love,

Us

September 2, 2016

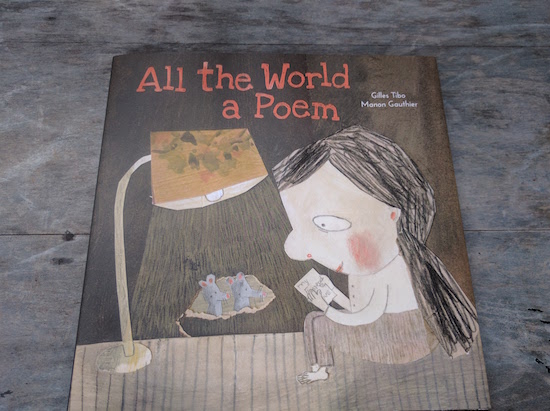

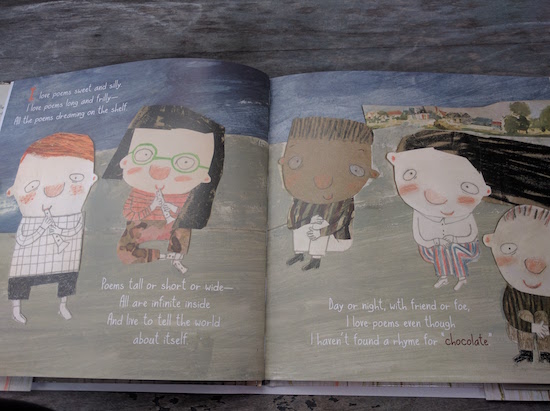

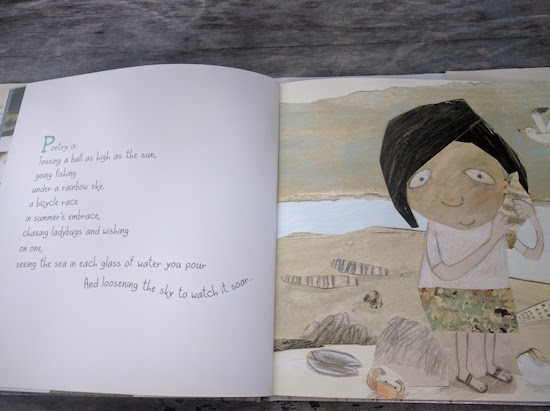

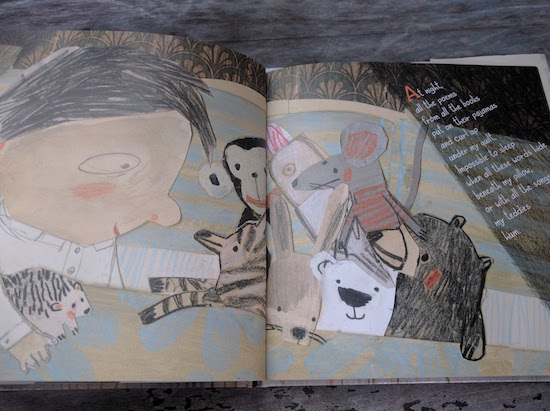

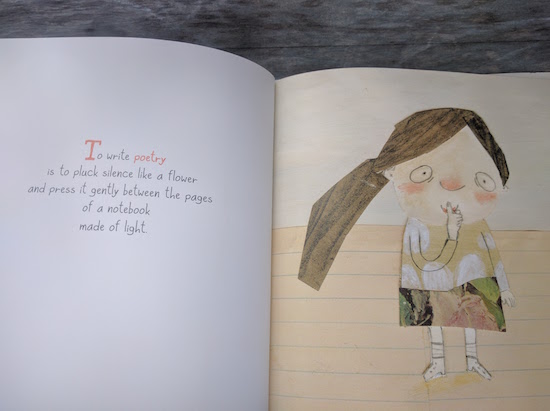

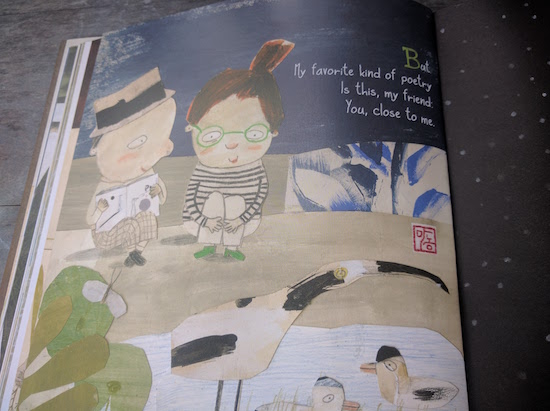

All the World a Poem, by Gilles Tibo and Manon Gauthier

I am totally in love with All the World a Poem, a celebration of the poetry in the world and the world that’s in poetry, written by Gilles Tibo and illustrated by Manon Gauthier, both award-winners in Quebec and internationally. And now their book has been beautifully translated into English by Erin Woods, whose task fascinates me in what it means to translate a poem, poems being is so intrinsically about their language. It’s building the same object out of a different material, and I’m thinking about what changes, what’s retained, and how the translated poems are enriched even, deepened. The translation adds an entire level of meaning to what is already a deeply textured book. Woods delivers full credit for her role in making a book that’s so extraordinary.

Each spread is a different poem celebrating poetry as diverse as the poets who write it, and sometime the poetry is literal (concrete?) and sometimes the poetry is simple (not simple) wonder at the world around one, ephemeral moments and fleeting flyaway things.

Sometimes the poems are loose and free (verse) and other poems rhyme with metre, not all of them obvious and my eldest felt particularly pleased with herself when she thought she’d figured one out.

My favourite page is the one above, silence like a flower pressed between the pages of a notebook made of light. The poems themselves all sophisticated and yet accessible, like the illustrations with their childlike renderings and the richness of texture. Inspiring young readers to see the poetry at work in life and the world, to read it, and maybe even to sit down and write it.

August 31, 2016

Extraordinary Day

My favourite thing about being a parent is the way you get the make the world magic. The way you can wave an imaginary wand an transform an ordinary day into a extraordinary one. The way that my children had no idea what was up when we told them to get their shoes on at 8:30 this morning, and when they kept asking where we were going, we said they’d find out when they got there. They’d been expecting their daddy to leave for work as usual, but there we all were marching to the subway, south to Union. And then a walk along Front Street, and over the train tracks to the aquarium, because Harriet’s loves the aquarium, and had expressed a wish to go there again. There you go Harriet: wish granted. Amazing.

We had a terrific time at the aquarium, and the best part was when we ran into my best friend Jennie. After a few hours we were done though, and the place was completely bonkers, and so we left and meandered north to the place that had perhaps inspired this whole aquarium plan—the close-in-proximity, brand new Penguin Bookshop.

A bookstore that fits in your pocket, it is, or your closet, at least. Formerly a shoe repair kiosk. It features a lively selection of Penguin-branded goods and books they publish, Canadian and classic. I got the new Dave Eggers novel and The Bloody Chamber, by Angela Carter, and we bought a copy of Ooko because we’d had it from the library and loved it. It was very nice to finally stop by.

We had lunch at the Old Spaghetti Factory, which was completely fun, and totally not horrible or boring. And there was so much bread. The bad thing about being snobs who live downtown is that we don’t get free bread with our meals very often, and certainly not for lunch (and if we do, it’s spelt bread and nobody wants to eat it). The children thought the place was great and we thought it was surprisingly good, the perfect place to stop on this day of being tourists in our own city for a while.

“And what are you doing with the rest of your day?” our waiter asked us as we paid our bill. “We’re going to visit Toronto’s First Post Office,” I told him. I told him, “You’ve probably been there a hundred times, right?” He gave me a look. When he finally bid us adieu, he said, “Have fun at the…post office.”

But not just any post office! It’s an actual working post office (and woo hoo! Canada Post and its employees have finally come to an agreement so we’re not going to be having a postal strike) AND a museum. From the restaurant, we walked through the beautiful St. Lawrence neighbourhood to get there, and finally arrived. Full disclosure, the children were being to lose their shit by this point.

At Toronto’s First Post office you get to try writing with quills, and can also purchase stationary to write letters in their reading room. The place was marvellously busy, with tourists and also people coming in on ordinary errands. After finding out that writing with quills was really hard, Harriet and Iris sat down to write with ordinary pens, and they both ended up crying because a) over the summer Harriet had lost any writing skills she’d ever possessed and b) Iris had never possessed any anyway. And all I wanted to was write a letter to my friend, but the children were bananas and also doing dangerous deeds with ink, which ended up smeared all over Iris’s body, and then she blotted it with the sand provided for such things, and it all had gone a little bit awry. We pulled it together though, got letters written and even posted. And then it was time to admit that the day was coming to an end, so we headed for the subway, and nobody cried again, I think, so it all was a success.

August 30, 2016

Mister Nightingale, by Paul Bowdring

In my friend Mark Sampson’s review of Paul Bowering’s last novel, the award-winning The Stranger’s Gallery in The Fiddlehead, he wrote, “Bowdring’s prose bursts with such clarity and assuredness that you trust his voice to take you anywhere it wants…” I know this because this excerpt from Mark’s review appears inside the ARC for Bowering’s latest novel, Mister Nightingale, and when I read that line, I thought, “Exactly.” Because while the notion of Bowdring’s novel as a “novelist’s novel” appeals to me—I love his send-up of literary culture, of small press politics, of comradeship and competition between writers, and all of that insider baseball—Mister Nightingale isn’t the kind of book I can manage to get through. And not just because it’s written by a man (she writes, unabashedly wearing her bias on her sleeve), because it’s about a man whose own literary bedrock is so definitively male. It’s all Kafka and his frozen heart, and James Joyce, and Proust, and all those people I’ve never read and never will because so many other people read them already that I don’t have to. Because I don’t trust any writer who doesn’t have a single literary foremother, or at least ten of them, and Bowdring’s James Nightingale never references one.

In my friend Mark Sampson’s review of Paul Bowering’s last novel, the award-winning The Stranger’s Gallery in The Fiddlehead, he wrote, “Bowdring’s prose bursts with such clarity and assuredness that you trust his voice to take you anywhere it wants…” I know this because this excerpt from Mark’s review appears inside the ARC for Bowering’s latest novel, Mister Nightingale, and when I read that line, I thought, “Exactly.” Because while the notion of Bowdring’s novel as a “novelist’s novel” appeals to me—I love his send-up of literary culture, of small press politics, of comradeship and competition between writers, and all of that insider baseball—Mister Nightingale isn’t the kind of book I can manage to get through. And not just because it’s written by a man (she writes, unabashedly wearing her bias on her sleeve), because it’s about a man whose own literary bedrock is so definitively male. It’s all Kafka and his frozen heart, and James Joyce, and Proust, and all those people I’ve never read and never will because so many other people read them already that I don’t have to. Because I don’t trust any writer who doesn’t have a single literary foremother, or at least ten of them, and Bowdring’s James Nightingale never references one.

And yet, there was something about the narrative. While in most books, the lack of foremothers would be off-putting, I was willing to forgive it of Mister Nightingale. Because of what Mark wrote about the clarity and assuredness of Bowdring’s prose that I trusted enough to follow. Because (and I am not kidding, this is usually a deal breaker for me): in the entire book, there is not a single blowjob (and this is another reason why I tend to avoid books by men. Ubiquitous blowjobs. They go on for paragraphs and paragraphs. It’s really quite unbearable). And because there was this strange and uncanny echo in the novel of Carol Shields’ Unless, and I’m not saying this was anymore than me making weird connections, but they were vivid ones. James Nightingale, like Reta Winters, a semi-successful novelist, belying the ordinary lives and concerns behind the writer’s persona. James’ estranged wife is called Alicia, who plays viola in an orchestra, although in Reta Winters’ fictional novel, her heroine Alicia is engaged to a man who plays trombone in an orchestra, and so the lines aren’t exactly parallel, but still, one reminds me of the other. Mister Nightingale raises the question of unlived lives, as does Unless and also Shields’ The Stone Diaries, James considering the experiences of his neighbour who discovers her freedom and possibilities when her husband dies and her children are grown, and he also considers his own lives, the ones he might have lived, had he made other choices. Both characters also deal with the demands of elderly parents, and the peculiar, tangled nature of relationships with daughters on the cusp of womanhood. In many ways, these books are spiritual siblings. I think they’d get along.

Mister Nightingale begins with James’ return to his native Newfoundland after 30 years away. He’s even missed his own mother’s funeral, but now they’re offering him an honorary degree, and a local press is reissuing his first book. Plus his marriage has ended in Toronto and he doesn’t know what he’s going to do next, so it seems like a good time to return to the scene of the crime. The crime being the small press publisher ripping off James’ friend, the poet, Kevin, who didn’t get paid for sales of his book and who was furious to discover his poetry published in a high school English text and he hadn’t been paid for that either. So naturally, things are going to get more than a bit interesting at James’ book launch (although the date for that event is being postponed over and over again, in absolutely true small press fashion).

But in the meantime, James takes stock of his life, tries to reconnect with his father, encounters ghosts from his past, learns all the ways that Newfoundland has changed and stayed the same in the last three decades, and keeps some tabs on his daughter, who has just started university in St. John’s. He becomes reacquainted with his sister, gets a Newfoundland driver’s licence, partakes in an ill-attended book signing at the local Chapters, and gets drunk on local TV.

All of which is to say that the novel is not terrible plot-driven, but we go there anyway, with pleasure even, for all the reasons recounted above. Mister Nightingale is a smart, funny and absorbing book, and I’m so glad I went along on its journey.

August 29, 2016

The Art of Blogging begins again…

My very favourite part of my blogging course is week 6ish when we talk about what blogging has to do with cake, getting lost, Maira Kalman’s The Principles of Uncertainty, and hope in the darkness. If you care to take a crash course, you can do so here, but if you feel like joining us, I’m pleased to let you know that The Art of Blogging starts on October 3 and runs until the end of November at the University of Toronto’s School of Continuing Studies. You can register now, and I do hope some of you can make it.