September 28, 2016

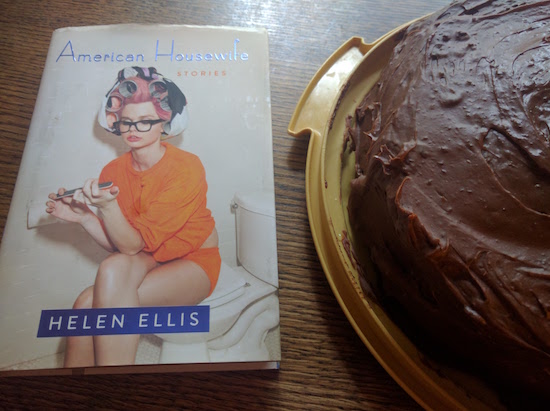

American Housewife, by Helen Ellis

I bought Helen Ellis’s American Housewife after reading about it plenty, and then reading more in Laura Miller’s article on Housewife Fiction (which led me to Diary of a Mad Housewife, by Sue Kaufman, which I loved so much and should surely be brought back into print). I bought it at Ben McNally Books after asking at the counter for a book “with a woman in rollers on the cover, written by someone whose first name is Helen” (because I have become that bookshop patron as my mind begins to fade), and they found it for me. I read it sometime in the summer, but didn’t write about it here, not because it was insubstantial necessarily, but because it was so digestible that I didn’t really need to work through it. Reading this book was like reading a magazine, which I think was meant to be part of its appeal, with the lists scattered throughout between stories and numerous pieces with a didactic bent i.e. “How to be a Grown-Ass Lady” or “How to Be a Patron of the Arts.” There was a surface the reader could skim, is what I mean, though there is more going on if the reader dares to probe deeper.

But there is a limit to the probing (this is not a sexual metaphor, you pervert) because this book is pretty short. It is the most terrific package, a miniature hardcover, cute cover, appealing design on the spine. It is easy to objectify this book and to appreciate it, and yet my book club colleagues who work in publishing were confused about it. People don’t buy short stories, they affirmed, and yes, this is a slight book, but it’s a hardcover, more than 30 dollars. Who was meant to be a audience? Well, me, I thought, although I also know that my singlehanded efforts to support the publishing system have not been seeing the results I’ve been hoping for, so perhaps that wasn’t the most excellent plan.

Anyway, this book is intriguing. It fascinates me that it was borne of a Twitter account (@WhatIDoAllDay), and the resulting snappiness of the book’s contents. It intriguingly plays with the line between autobiography and fiction (in the way that social media in general does) and I’m interested in domesticity as divorced from motherhood, which we don’t see very often. For many women, motherhood offers a direction to one who is otherwise lacking such a thing (for better or for worse) but what do women do if they don’t pursue that option? There is a scathingness to the writing here, and my book club friends wondered just who was being satirized, and if Ellis was reviling her very readers (middle age ladies in book clubs) but I argued that she was implicating herself. This is a book about wanting to write and not writing, or else writing but not being being published (the distinction Ellis describes as the distance between Wimbledon and hammering a tennis ball against the garage door), its about the paralysis of too much choice and women’s roles and living with failure and compromise, and it’s funny, nasty and kind of amazing. We loved its Southern lady/Southern gothic vibe, and the Shirley Jackson darkness, and that John Lithgow appears as a character. I like that Helen Ellis is also a professional poker player, which seems at odds with her southern lady persona, but that is the point of southern lady personas, I think, the surprises that lie beneath an exterior of conventionality. The same could be said of the book. We all had different stories we’d connected with and others not so much, and there was so much to think about, and argue about, and even to agree upon.

And afterwards, we all ate cake.

September 26, 2016

The Dependent, by Danielle Daniel

I have tremendous admiration for author/illustrator Danielle Daniel, whose picture book, Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox, was one of the best picture books I encountered last year, a finalist for the First Nations Community Reads Awards, and which has recently been nominated for the prestigious Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Award. And so when I learned she’d written a memoir, I know I wanted to read it.

I have tremendous admiration for author/illustrator Danielle Daniel, whose picture book, Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox, was one of the best picture books I encountered last year, a finalist for the First Nations Community Reads Awards, and which has recently been nominated for the prestigious Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Award. And so when I learned she’d written a memoir, I know I wanted to read it.

The Dependent is a memoir about her remarkable marriage, a relationship that begins when a headstrong Women’s Studies major meets a handsome guy in the Canadian army, and they embark upon an adventure together that requires plenty of compromise on her part. Daniel doesn’t fit the traditional mould of an army wife, and is continually frustrated by the army’s demands upon her family and also her husband’s willingness to do as the army required in order to further his career. She writes with brutal honesty about her anger and also about her experiences with depression, which begin in this memoir after she experiences a miscarriage. She also alludes to a troubled family background that colours her experience of the present and makes her a jealous and mistrustful partner. Her husband Steve, however, does not have a lot of sympathy for his wife’s point of view—like a good soldier, he doesn’t delve into complicated emotions and focuses on his mission, one thing after another. He is frustrated that his wife does not seem to have ability to work through her unhappiness.

9/11 changes the stakes for members of the military serving around the world, and so too for Danielle does the birth of her son—although Steve leaves home for three months just weeks after the birth. She is relieved when Steve finally receives a position in Canada that keeps him from having to serve overseas, but what she thinks is to be their happy ending turns into another kind of story when Steve is injured in a parachute jump and is left a paraplegic. Suddenly Danielle is no longer married to the army—and in fact the support offered to their family is almost laughable inadequate—but her husband’s disability is something new and just as complicated to navigate. What makes the book so interesting is that Steve rebounds from his injury the same way he does from everything, and the dynamics of their marriage remain unchanged: Steve goes back to school, begins to train as an athlete training for the Paralympics, and becomes a local celebrity. Meanwhile Danielle is lost is the same shadows that had been following her for years, not to mention her husband is altogether dependent on her in so many ways, and she doesn’t know who she is beyond his wife. She is angry with Steve and with the army from what it stole from them, and tired of years of compromise, and Steve is understandably upset that she is wallowing in her pain all the while he’s the one who’s been injured. He doesn’t understand that she’s been a victim too.

Years of simmering tensions come to ahead eventually, and getting to this point makes for a fascinating read. I was impressed how surprising the dynamics were between Steve and Danielle, complicated by the fact that they’re two actually human beings with all the baggage and complexities inherent. While some of the dialogue between them seemed awkward and stilted, containing the same kinds of arguments over and over (which is a marriage problem as well as a narrative one), that would be my one criticism of The Dependent. What blew me away about it, however, was its structure, Daniel’s remarkable deftness with chronology, which makes me think of her art, collage, layers and textures. The Dependent is not told in chronological order, but instead weaves in and out of time (because the idea of time as a line is a point the narrative itself serves to refute. We carry all this stuff with us). The playing with time and story, the giving and withholding of detail, is stunningly accomplished, which is only underlined by the book’s incredible, miraculous and beautiful ending, which is also its beginning, a fantastic, complicated and beautiful love story, and isn’t that always the way…

September 25, 2016

My Literary History, via the Victoria College Book Sale

I must have gone to the Victoria College Book Sale when I was student there (and when I worked at the Victoria College Library, which the book sale supports) but I don’t really remember it. My appetite for books then was more theoretical than practiced, and I didn’t yet have tastes of my own. When pressed, I would have told you that I admired Margaret Atwood, but looking back, I don’t think I had any idea what she was up to in her work. I was still reading the books I thought I was supposed to be reading back then, buying battered paperbacks with familiar names—Thomas Hardy, DH Lawrence. They were always men. It makes total sense now that I didn’t have very much fun reading these books, or even remember them. I recall reading The Years, by Virginia Woolf in my undergraduate years, and finding it all very difficult to decipher. I remember reading it again in the months before I went to graduate school, and being able to make sense of it, and being oh so relieved—perhaps I was finally getting smarter.

It was in the years I was out of school that I finally figured out who I was as a reader. Living in England helped, with its omnipresent literary culture, but after that I lived in Japan, and that helped too. To go from being overwhelmed by print culture to being functionally illiterate was amazing, and having so few books available to me—we read whatever we could get our hands on. I don’t know that there has ever been a more important bookshop for me ever than Wantage Books in Kobe, where I first found Margaret Drabble’s The Radiant Way, and also Carol Shields Various Miracles. It occurs to me that as a reader and I writer, I was actually born there.

I returned to Toronto in 2005, to attend graduate school at the University of Toronto, and I returned also to my job at the EJ Pratt Library. We were so poor then, as I attended school, and Stuart waiting for his permanent residency, without which he was unable to work. When I went to the Victoria College Book Sale in 2005, I remember knowing I probably shouldn’t. We didn’t have the money for it. And me being who I am, and books being what they are, I ended up spending $14 (—this was the half-price Monday, I think) which was a terrific indulgence and one I appreciated so much. I wrote about it here, and reading that list now, these are all books that meant a great deal to me—Penelope Lively and Hilary Mantel (pre-Wolf Hall!). Over the next few years, I would buy everything from Margaret Drabble’s back catalogue at the Victoria College book sale, which fundamentally has been my gateway to major (mostly British) women writers. Laurie Colwin too, and Muriel Spark, Jane Gardam, Anita Brookner and Doris Lessing

2006 was the year I bought Interpreter of Maladies, by Jhumpa Lahiri, which my friend Kim handed to me saying, “You’ve got to read this,” wholly unaware that the blurb on the back by Amy Tan said precisely that this was the type of books that drives one to do such things. I was no longer poor by 2007, so bought about 20 books. In 2008, I purchased an actual tower—with Penelopes Fitzgerald, Lively and Farmer.

By 2009, I realized I’d bought all the books available at Half Price Monday and would have to up the stakes a bit. It was also the first year I went with a baby and the year I bought my first Barbara Pym—Excellent Women. In 2010, I left my baby at home, and went determined to buy books I really wanted to read and not ones that would simply gather dust on the shelf—that was also the year I bought Bronwen Wallace’s story collection, which has never been dusty.

2011 was the most fantastic year—Rachel Cusk, Isabel Huggan (who I hadn’t even read yet!), Lynn Coady, Caroline Adderson, Ali Smith, and more. I missed the Vic Book Sale in 2012—we were in Alberta for my sister’s wedding. It’s possible I missed it again in 2013, with a small baby in my life and an awareness that more books was the last thing I needed. I was perhaps still trying to get through the books I’d purchased two years before. But my small baby grew, and in 2014, she screamed the entire time I was browsing, which solved the problem of too many books (and not because I cut my browsing short, but just because the screaming baby made it hard to concentrate)—that was the year I bought just two books!

Last year I got to go child-free, a few hours stolen while Harriet and Iris were at school—that was when I got a box of Narnia and Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Blue Flower (which I would turn out to love, against all my expectations, but in accordance with everyone else’s).

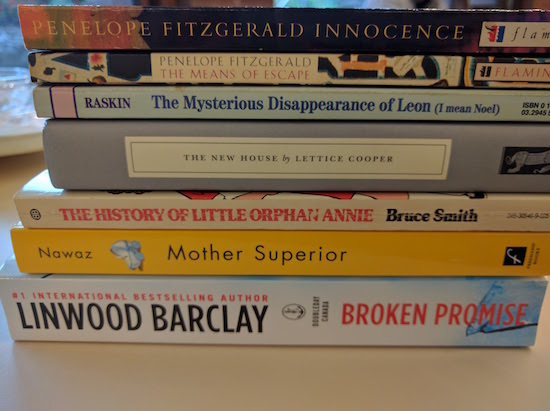

And now this year, which is the whole point of this post. Believe it or not, I did not actually intend to write my autobiography via my history of the Victoria College Book Sale, but that seems to be just what I’ve done. And this year was a very good haul. Penelope Fitzgerald seems to be the one author left whose books I was discover via the book sale—I got Innocence and The Means of Escape. The Mysterious Case of Leon, by Ellen Raskin, whose The Westing Game is so beloved by me and I reread it in December when I was sick. This novel is meant to be quite different, but it’s full of her characteristic illustrations (she wrote wacky picture books during the ‘sixties, and did you know she designed the original cover of A Wrinkle In Time?) and I think I’ll like it.

I got The New House, by Lettice Cooper, because a Persephone Book for $5 is a deal not to be missed, though I know nothing about Lettice, except that Jilly Cooper married her nephew and wrote the intro to this edition. The History of Little Orphan Annie, by Bruce Smith, was a STEAL for $1, and perhaps a book that had been waiting its whole life to get to me, and this is why I love book sales, the serendipity. Mother Superior is the first book by the excellent Saleema Nawaz, and I wanted to buy this book when I visited her in Montreal this spring, but it wasn’t on the shelf, so I was glad to get this copy. And finally, Broken Promise, by Linwood Barclay, because the number of amazing writers and readers who testify to his greatness are legion. I think this one will be fun.

The Victoria College Book Sale seems as much apart of my autumn as the leaves changing colour, or the kids heading back to school. A pleasure in recent years is encountering friends there without even having made plans to do so. This year, we followed up our book browsing by heading out for lunch together, and admiring all new acquisitions, revelling in the goodness of books.

September 23, 2016

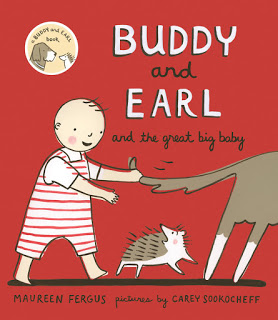

Buddy and Earl and the Great Big Baby

Today for #PictureBookFriday, I’m relinquishing book review duties to Harriet, who has started a blog to explore her fascination with hedgehogs and whose latest post is a review of Buddy and Earl and the Great Big Baby, by Maureen Fergus and Carey Sookocheff, which is the funniest Buddy and Earl book yet (and that is saying something). We love this series, and not just because it features an adorable hedgehogs (although that helps).

September 21, 2016

Book Catch-Up

Heroes of the Frontier, by Dave Eggers: I stopped reading Dave Eggers at some point (after What is the What, I think, which I loved, although I am not sure I still would…) and I’m thinking that was probably the right idea. I bought his latest novel because I’d heard intriguing things about it, and while I’m glad I read it and liked lots of things about it—there are good bits and he writes children so brilliantly, in particular the younger child who reminded me of my own feral creature who also likes to scream disrespectful things at inanimate objects—but it was too long and rudderless. Actually reminded me a bit of Vendela Vida’s Let the Northern Lights Erase Your Name, which I loved years ago, and also the movie, Away We Go, which Vida and Eggers wrote together. The ending was so good, so I closed the book satisfied, and there were plenty of points throughout where I gasped or laughed, but I was put off my the narrative’s rudderlessness. Why are we floundering, I kept wondering. Which is perhaps a point about nationhood and existentially as well, but for a near-400-page book gets a bit annoying. Thinking about A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius with its footnotes and that novel he wrote after (in my copy the text started on the cover and ran right through to the back cover) and his tendency to have the narrative swell to fill all available space, literally and otherwise, and I am not sure that it’s an altogether good thing. But Dave Eggers gotta be Dave Eggers. I don’t know. He’s interesting. But also not—although he is always more interesting than any arguments disparaging his work and character. There is nothing more boring than hating Dave Eggers. I do think the novel is worth picking up for the depiction of its children, which is remarkable. Not everybody will be able to get through it though….

Heroes of the Frontier, by Dave Eggers: I stopped reading Dave Eggers at some point (after What is the What, I think, which I loved, although I am not sure I still would…) and I’m thinking that was probably the right idea. I bought his latest novel because I’d heard intriguing things about it, and while I’m glad I read it and liked lots of things about it—there are good bits and he writes children so brilliantly, in particular the younger child who reminded me of my own feral creature who also likes to scream disrespectful things at inanimate objects—but it was too long and rudderless. Actually reminded me a bit of Vendela Vida’s Let the Northern Lights Erase Your Name, which I loved years ago, and also the movie, Away We Go, which Vida and Eggers wrote together. The ending was so good, so I closed the book satisfied, and there were plenty of points throughout where I gasped or laughed, but I was put off my the narrative’s rudderlessness. Why are we floundering, I kept wondering. Which is perhaps a point about nationhood and existentially as well, but for a near-400-page book gets a bit annoying. Thinking about A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius with its footnotes and that novel he wrote after (in my copy the text started on the cover and ran right through to the back cover) and his tendency to have the narrative swell to fill all available space, literally and otherwise, and I am not sure that it’s an altogether good thing. But Dave Eggers gotta be Dave Eggers. I don’t know. He’s interesting. But also not—although he is always more interesting than any arguments disparaging his work and character. There is nothing more boring than hating Dave Eggers. I do think the novel is worth picking up for the depiction of its children, which is remarkable. Not everybody will be able to get through it though….

A Great Reckoning, by Louise Penny: I do think that Chief Inspector Gamache has been feeling a bit aimless since his retirement in How the Light Gets In about three years back. But in her latest novel, Penny gives him a task and a half: he’s charged with leading the police academy and rooting out its forces of corruption. It’s a novel that has resonance and relevance in light of constant stories about police brutality and #BlackLivesMatter, and it also returns us to Three Pines (don’t worry—Gamache and his wife still have their home there, although they also have a small apartment at the academy) where residents have found a mysterious map hidden on a wall, a map on which Three Pines appears and perhaps the last one upon which it ever did. What does the map symbolized? And yes, who is behind the murder that takes place at the Police Academy soon after Gamache’s arrival, a murder in which he is a suspect? The answers to both questions become intertwined, and connected to a long-ago tragedy from the Chief Inspector’s past which becomes clear at the novel’s devastatingly lovely conclusion.

A Great Reckoning, by Louise Penny: I do think that Chief Inspector Gamache has been feeling a bit aimless since his retirement in How the Light Gets In about three years back. But in her latest novel, Penny gives him a task and a half: he’s charged with leading the police academy and rooting out its forces of corruption. It’s a novel that has resonance and relevance in light of constant stories about police brutality and #BlackLivesMatter, and it also returns us to Three Pines (don’t worry—Gamache and his wife still have their home there, although they also have a small apartment at the academy) where residents have found a mysterious map hidden on a wall, a map on which Three Pines appears and perhaps the last one upon which it ever did. What does the map symbolized? And yes, who is behind the murder that takes place at the Police Academy soon after Gamache’s arrival, a murder in which he is a suspect? The answers to both questions become intertwined, and connected to a long-ago tragedy from the Chief Inspector’s past which becomes clear at the novel’s devastatingly lovely conclusion.

Don’t I Know You, by Marni Jackson: I have this idea that my mother spent the years before I came into the world singing “Hey Jude” in downtown pubs in grand singalongs and running around Europe with an accordion playing “Those Were the Days, My Friends”, by Mary Hopkin. By virtue of my parents being baby boomers, I was born nostalgic for a world I never knew—I remember listening to “Carey” by Joni Mitchell when I was fifteen and anticipating a time when I’d have gotten used to clean white linens instead of scrambling down in the street. To be honest, things never worked out so well for me textile wise, but these all remain my cultural touchstones, never mind they happened long before my time. I’ve always wanted to go down to the Mermaid Cafe, which is a huge part of the appeal of Marni Jackson’s fiction debut, whose unique premise is that each story in this linked collection hinges on a fictional encounter with a celebrity, celebrity itself being a kind of fiction—the Brangelina breakup notwithstanding because that shit is real. Anyway, the premise is neat but not the point and eventually becomes secondary to the stories themselves, which are beautifully crafted, full of surprising turns of phrase and plot, and take us through the life of Rose McEwan from age 17 (when she enrols in a writing workshop taught by John Updike) to 67 (when she embarks on a canoe trip accompanied by Leonard Cohen, Karl Ove Knausgaard and Taylor Swift). In between, Van Morrison drives a TTC bus into the mystic, Adam Drive shovels her snow, Gwyneth Paltrow gives her a facial, and Joni Mitchell gives her the lowdown on the perils of free love. This is one book you can certainly call an original, and it’s one that has been staying on my mind.

Don’t I Know You, by Marni Jackson: I have this idea that my mother spent the years before I came into the world singing “Hey Jude” in downtown pubs in grand singalongs and running around Europe with an accordion playing “Those Were the Days, My Friends”, by Mary Hopkin. By virtue of my parents being baby boomers, I was born nostalgic for a world I never knew—I remember listening to “Carey” by Joni Mitchell when I was fifteen and anticipating a time when I’d have gotten used to clean white linens instead of scrambling down in the street. To be honest, things never worked out so well for me textile wise, but these all remain my cultural touchstones, never mind they happened long before my time. I’ve always wanted to go down to the Mermaid Cafe, which is a huge part of the appeal of Marni Jackson’s fiction debut, whose unique premise is that each story in this linked collection hinges on a fictional encounter with a celebrity, celebrity itself being a kind of fiction—the Brangelina breakup notwithstanding because that shit is real. Anyway, the premise is neat but not the point and eventually becomes secondary to the stories themselves, which are beautifully crafted, full of surprising turns of phrase and plot, and take us through the life of Rose McEwan from age 17 (when she enrols in a writing workshop taught by John Updike) to 67 (when she embarks on a canoe trip accompanied by Leonard Cohen, Karl Ove Knausgaard and Taylor Swift). In between, Van Morrison drives a TTC bus into the mystic, Adam Drive shovels her snow, Gwyneth Paltrow gives her a facial, and Joni Mitchell gives her the lowdown on the perils of free love. This is one book you can certainly call an original, and it’s one that has been staying on my mind.

September 20, 2016

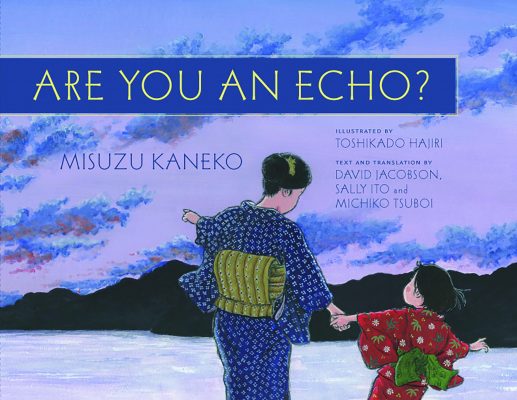

Review: Are You An Echo?

Japan was my home for a while more than a decade ago, and it’s a place I’ll always be grateful to for its generosity, goodness, and what living there taught me about being a person in the world. And so I was especially pleased by the opportunity to review Are You An Echo?, a new book that’s part poetry collection, part biography, and a remarkable collaboration between many different people. It translates Misuzu Kaneko’s poetry into English for the first time, the poems complemented by her difficult life story, and also by the lost-and-found story of these poems themselves, which were “rediscovered” by the Japanese public when the poem “Are You An Echo?” was aired in public service messages on television after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

From my review:

…it seems fitting that Are You an Echo?, a book that brings Kaneko’s work and life story to English readers, is also an exercise in connection. The effort is a unique collaboration between American writer and translator David Jacobson, Canadian translator Sally Ito, Japanese translator Michiko Tsuboi (who studied at the University of Alberta), and Japanese illustrator Toshikado Hajiri. Editor and translators’ notes explain the fascinating creative process involved in this genre-bending mash-up, including on-the-ground research in Japan.

September 19, 2016

Swimming

Emboldened by the fact of my children being enrolled in school between the hours of 9 and 3, and inspired by blog Swimming Holes We Have Known (which had me craving blue waters all summer long), I joined the university swimming pool last week, which is conveniently located minutes from my house and the playschool. For a half hour every day, I’ve been swimming lengths in the medium-slow lane, usually just after writing my daily 1000 words of my novel (which hit 71,000 words last week) and so I’m usually mediating on problems of character as I swim (and also pondering what Mad Men has taught me about storytelling). The last time I swam regularly was when I was pregnant with Harriet, which I wrote about here, and so the whole experience in terms of senses and psyche is tied up with the feelings of physical well-being I felt during that time, and also something womb-like, which is not original or such a stretch, but still. It’s the only kind of exercise that I don’t hate—that I love, even (though we’re only one week in, but still there’s something to this).

September 18, 2016

How to Make the Most of the Last Weekend of Summer, in 7 Easy Steps

Step 1) Assemble your squad.

Step 2) Look out the window on the way.

Step 3) Follow the rules.

Step 4) Bring too much cake.

Step 5) Ride the highs and the lows.

Step 6) Remember to always stick together.

Step 7) Never forget the place you came from.

Step 7) Look up for the sunset.

September 15, 2016

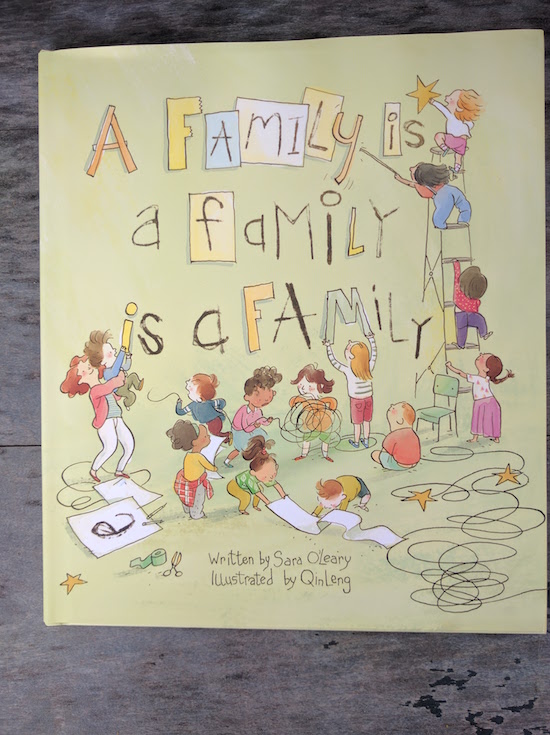

A Family is a Family is a Family, by Sara O’Leary and Qin Leng

There is a special place in my heart for short picture books. And not just because they’re the best books to read on those nights when the day has been long and after-bedtime can’t come soon enough. But also because the best ones manage to be expansive, to incite questions and ideas and discussions, and Sara O’Leary and Qin Leng’s A Family is a Family is a Family is no exception.

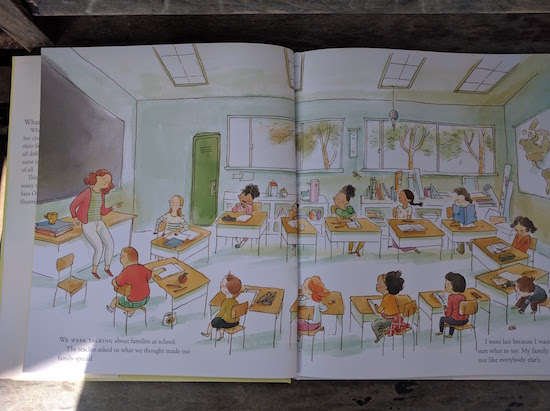

It begins with a classroom discussion, one that could possibly be quite fraught: What makes your family special?

“I went last,” our narrator tells us, “because I wasn’t sure what to say. My family is not like everyone else’s.”

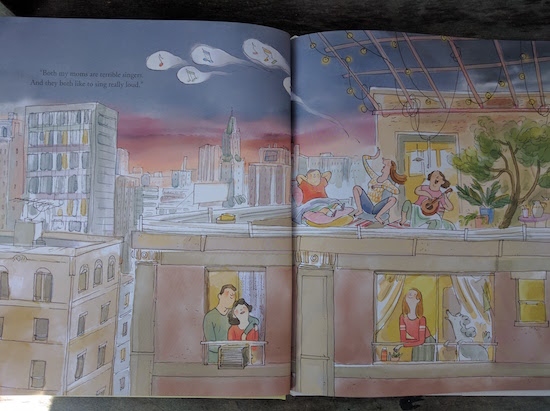

But the revelation of the class discussion is that no one’s family is like every one else’s. And in simple sentences delivered from a child’s eye view we learn what is indeed special about so many different families, the families’ diversity inferred by the reader but diversity not necessarily the speciality, because this is a book about specifics: “Both my moms are terrible singers. And they both like to sing really loud.”

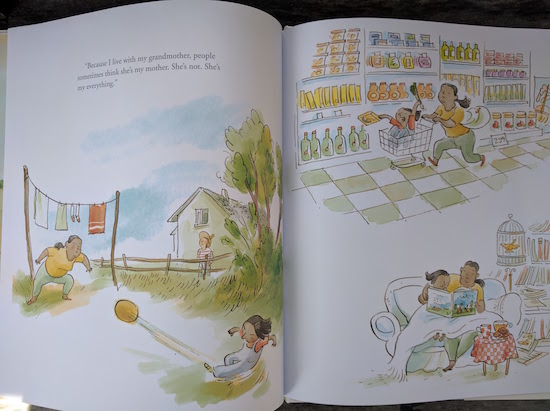

From the child whose parents won’t stop kissing to the family with so many kids, the family with split custody, the blended family, the single parents, two dads, and the child who lives with her grandparents (“Because I live with my grandmother, people sometimes think she is my mother. She’s not. She’s my everything.”)—O’Leary’s story paints a varied and celebratory picture of the many ways there are for a family to be. Leng’s illustrations add richness and texture to the simple prose, with their action-packed and cluttered scenes that suggest a marvellous mess of abundance (which, of course, is love).

In the end, the narrator shares an anecdote in which they’re at the park and a woman asks her foster mother to point out which are her real children.

“Oh, I don’t have any imaginary children,” Mom said. “All my children are real.” (…An idea that took me back to Jo Walton’s My Real Children, which is a novel I loved so much).

This book is terrific for its celebration of family in many forms and of diversity, but also for conversations in general about what a family means and how one is defined. “What makes our family special?” a reader is bound to ask herself after finishing the book, and considering such things—as well as the ways in which we have to nurture our own families as little institutions, a home base in the big wide world—can only do us good.

September 13, 2016

Winter Wren, by Theresa Kishkan

I’d been reading Theresa Kishkan’s novella for a while, the first release from her imprint, Fish Gotta Swim Editions, whose books are designed by the talented Anik See (and oh, this little book is so lovely). And I thought I’d found an error. The book takes place in 1974, and there is a reference to the protagonist being born in 1915, and I thought, “No, wait.” A typo, I figured. She’d been born in 1945. And I still don’t know why I was so insistent on the error, that Kishkan’s character could not have possibly been 59 years old, except for the fact that I rarely encounter a woman in fiction who is 59 years old. And if I do, she is peripheral, or her identity is wrapped up in being somebody’s wife or mother.

I’d been reading Theresa Kishkan’s novella for a while, the first release from her imprint, Fish Gotta Swim Editions, whose books are designed by the talented Anik See (and oh, this little book is so lovely). And I thought I’d found an error. The book takes place in 1974, and there is a reference to the protagonist being born in 1915, and I thought, “No, wait.” A typo, I figured. She’d been born in 1945. And I still don’t know why I was so insistent on the error, that Kishkan’s character could not have possibly been 59 years old, except for the fact that I rarely encounter a woman in fiction who is 59 years old. And if I do, she is peripheral, or her identity is wrapped up in being somebody’s wife or mother.

Of course, I’ve met old women in literature, characters at the end of their lives, unravelling—Hagar Shipley. And there is no shortage of women in their twenties, thirties, forties, but there seems a paucity of women characters in their fifties. In general, I mean, and perhaps these books are out there and I’m just not reading them. But I’m not reading them, which is why the idea of a 59 year old woman still exploring, growing and transforming seemed remarkable to me. And then it became not remarkable at all, and I became aware that what was remarkable was this literary gap.

Winter Wren is the story of a woman, an artist, who returns from decades in Paris and the end of a love affair to Canada after the death of her mother, and makes a place for herself in an isolated cabin on Vancouver Island. She becomes preoccupied by the view from her window, and with the man who’d lived in her home before she bought it and who she visits in a home for seniors. He too is preoccupied by the view, and wishes she’d paint it for him.

Bring me the view at dusk.

Kishkan’s protagonist, Grace, is a character in one of her earlier novels, The Age of Water Lilies—Kishkan writes intriguingly of her novella’s genesis here. This book is a beautiful meditation of transformation and of place, and the line I loved best was, “Every morning I awake and am filled with a kind of quiet joy to realize where I am.”