April 4, 2017

Dear Pottery Barn Kids Sherway Gardens

Dear Pottery Barn Kids Sherway Gardens,

Dear Pottery Barn Kids Sherway Gardens,

Thank you for following me on Instagram. You have over 1300 followers, which is no small potatoes, and you are an internationally known brand located in a very good mall, so I should be flattered. And you’ve not only followed me, but you’re engaging with my posts, sharing baguette-related humour and being all ’round pleasant and fun. I feel like you and I could be friends…except you are a store. And you’re not just a store, you are a store that I can’t afford to enter because in order to afford your merchandise, I’d have to move up at least two income brackets. Do you know that I bought my kids’ bunkbed out of an actual garage in an industrial park at Jane and Finch? If you knew that, would you unfollow me? I showed my children a photo of the bunkbed on your feed that was built to resemble a playhouse, and they both went a bit gaga. They said, “Mommy, could we go there?” By which we all knew they really meant, “Is it possible to have another kind of life?”

I don’t know how they do it, those people who “engage with brands on social media.” How do you engage with a brand? When they make a joke on your instagram post, do you respond with, “Ha ha that’s funny by the way you’re a store”? Don’t get me wrong, I like stores. If I could afford to buy the playhouse bunkbed I’d be all over that shit. If you were having a clearance sale, I could possibly come in and purchase a facecloth (but only one that was on deep discount because a customer had bought it and returned it and the packaging had gone missing and someone had actually washed their face with it). But I don’t know how to talk to you. Everything in your posts is literally wearing a price tag or from a catalogue. How do you engage with a floor model? I don’t know what you look like. Do you even have a face?

Does a store dream, Pottery Barn Kids Sherway Gardens? Do you have hopes and fears? Do you cower at night in the silence of your mall and worry about climate change? As yuppies and their offspring traipse their dirty boots across your carpets in the daytime, do you ever wonder about the point of it all? What’s your favourite book? Your favourite recipe? Have you ever suffered from sexual dysfunction? Do you like cilantro? The artificial flavour for banana? What’s your favourite season? Do you have economic anxiety? Are you a public company? Do you ever consider your responsibility to your shareholders and then get really scared?

I want to know you. I want to be your friend and celebrate your birthday, and maybe even buy you a cup of coffee—but I can’t. So close you are, but still a world away. But maybe one day I’ll come across your wares on Craigslist and snap up something—a storage solution or an organic duvet insert—and maybe then this arrangement will all make sense. Perhaps one day I will understand.

Yours respectfully,

Me.

April 4, 2017

A Handy Guide to Explaining Graphic Anti-Choice Public Transit Ads to Your Children

“How am I supposed to explain this to my children?” is a question many people are grappling with in my hometown right now, where the city failed to fight a campaign by a group of fetus enthusiasts to display graphic anti-choice images on the sides of busses. Images that, I will remind you, are enlarged hundreds of times beyond their actual size, because (as a young man campaigning “for life” in the street once affirmed for me) if you showed images of abortions at their actual size (also known as REALITY) “they wouldn’t have any impact.” Which should give anyone pause…

But apparently not, because the ads are due to start running this week. As someone who has already talked about these ads with my children, however, I have wisdom to impart here which might be relevant to other parents. This is how I gave them the lay of the anti-choice land.

- A lot of things happen to women in their lives, I tell them. A lot of women have babies. And many women who want to have babies end up having their babies die before they are born, often for no reason that anyone can discern. And other women who want babies find out far into their pregnancies that their babies are not growing properly and they make the decisions to end their pregnancies—which is a painful, agonizing choice to have to make and leave families sad for a very long time. Other women find out they are pregnant when they don’t want to be, and these women can also make the choice to end their pregnancies, and sometimes this is sad and sometimes it isn’t.

- And then I remind them that the fact that women get to make choices about their own bodies makes a lot of people really angry. Sometimes those people are men and sometimes they are women. Sometimes they are people who themselves have lost babies they desperately wanted, which has left them unable to understand that their situation does not apply to everyone, that restricting someone else’s choice isn’t going to make their own loss any less. (And some of these people are pro-life dude-bro’s who are in their early 20s and as ridiculously empowered as they are ignorant about women’s lives and experiences. Mamas, don’t let your babies grow up to be pro-life dude-bro’s.)

- “A lot of people are huge assholes,” I remind my children. We see evidence of this everywhere. We try to love the world and humanity anyway, however. It is an ongoing project.

- And these huge assholes, I tell my children, have no problem with taking these intimate, personal, complicated experiences of women’s lives and driving them around town on the side of a bus via wholly misleading images. They have either not paused to reflect on or do not care in the slightest about how these images are as violent and cruel as they are misleading. On what it might mean to be coming home from the ER after realizing you are miscarrying and seeing that bus drive by you. Or even worse, when you’re waiting at the bus stop as you are miscarrying, and that’s the bus that pulls up. Public transit is not frequent enough in my hometown that you could just sit down and wait for the next one. I tell my children that the people who’ve placed these ads have not bothered to put themselves in that woman’s place, or the place of her partner, her children, all those people who know how complicated women’s health and women’s lives can be. I tell my children, Don’t be these people. I tell them there is such a thing as empathy. I tell my children: “In your lives, be better than that.”

- I tell them, “You know the problem, the reason these ads have happened at all and the reason people are able to rest afloat on the seas of their own ignorance, is that we don’t talk about abortion enough. A person lacking in curiosity might think that these aren’t issues that have affected nearly everyone. So in a way, even though the images are gross and fake, they give us cause to be grateful. Here we are talking about it. A good moment to remind you, my daughter, that your body—and the choice of what to do with it—is your own.”

April 2, 2017

Nine Years at Home

Nine years ago yesterday we moved here, the first day of April after a disastrous winter but then it never snowed again. “It’s always spring at our new house,” I remember thinking. There was mail waiting for us in the mailbox when we pulled up with the moving truck. A few days later we were awakened in the middle of the night by a digger out in the street carting away the snowbanks. I never knew such things were artificial, that the world could be arranged. But the fact that we’d moved at all was testament to the latter point. Before we moved here, every house we’d ever had had come to us via somebody else. Our old place in Little Italy had been my cousins’, and we’d lived in our friends’ old place in Japan, and company accommodation before that. But this apartment was the first home we’d ever been deliberate about. I found it online and it checked all of our boxes, except it had hideous carpets instead of hardwood floors. I remember how the sunshine poured into our old apartment that had hardwood floors on our last day there as we packed up the last few boxes (which ended up taking nine hours) and listening to Panic at the Disco and Sam Sparro. That night we slept on a mattress on the floor, and the movers would arrive in the morning. We were on the cusp of everything, and so excited to arrive.

Of course, we weren’t always sure. The day we moved in, our place was filthy and there was a box of rat poison in the bathroom—never a good omen. The drawers in the kitchen were filled with other people’s cutlery. Stuart and I ate pizza on the hideous carpet that night (which is the same hideous carpet I’m lying on now as I write this post) and he wasn’t sure at all, and so I had to pretend that I really was. It would turn out the the rat poison was for mice though, which is the sort of thing one expects in an old house downtown, and eventually I got the kitchen cleaned out. We painted the walls and hung our pictures upon them. I’ve written before about how we made a conscious decision to not buy a house, but how we were still in search of a home and that this would be the place. And living here has made so much possible for us.

Our apartment is in a great school district—who knew? I certainly didn’t in 2008 when our children were still strictly hypothetical. And this is the only home they’ve ever known, which has been scene to birthday parties, playdates, tantrums, and projectile vomiting. They’re wholly accustomed to the mildew in the bathroom, which has probably given them immune systems beyond compare. When they go to bed at night, the house is quiet, and it’s almost like it’s just the two us still, except for the plastic tubs of lego and the tiny table heaped with artwork. Nine years seems like a long time ago—the longest I’ve lived almost anywhere—but wasn’t it also five minutes ago? How is a person expected to keep such things straight?

Our house is weird, and not all of that is “charming”—although some of it is. There are rooms with wood trim that does not manage to go all the way around the room’s perimeter. There is an actual gap between the doors in the kitchen that means when you sit on one side of the table in the winter, you’re forced to contend with being on the windy side. Our oven is so small that you can only put two things inside it at once—and most of the time the pans don’t fit all the way and so I bake with the oven door partway open. The upstairs sink fell off the wall once while I was washing my feet in it. And the fact of that hideous carpet, which has not become any less hideous with time (although once we had children, we realized that attractive flooring was overrated).

But there are fairy doors, and a doorframe where two little girls’ height has been tracked, and big windows you can see the sky from, and the shade of a big tree that gives us gifts all spring and summer and well into fall. There is the chestnut tree out front where we get conkers. There are gorgeous tiles in the kitchen, and things to string bunting from, and a backyard where you can draw with chalk on the bricks and where my book club meets in summer, and where we get together with friends for epic barbecues. I’ve made two books here, and Stuart has honed his skills as a designer, and I remember him saying something once he’d calmed down about the potential rats, that there was something here that fostered creativity. Our houseplants lived a little bit longer than usual. There was something in the air.

There is a key that hangs outside on a rusty nail at the bottom of our staircase. I walk past it at least twice a day, but it took a long time for me to even notice it. “What’s the key for?” someone asked—perhaps our former downstairs neighbour. Nobody knew, but it’s been there forever. A curious thing—a very public spot for something that’s locked. What’s the point of a key that everyone has access to? It’s kind of emblematic of this place, its quirks and mysteries and possibilities, and the stories of all the people who’ve lived here before us. It’s emblematic of faith as well, which is the thing that brought us here. And so we keep the key hanging there, on the off-chance that one day we’ll need it.

March 31, 2017

The Everywhere Bear, by Julia Donaldson and Rebecca Cobb

My favourite Julia Donaldson is Julia Donaldson with Rebecca Cobb in The Paperdolls (even if I do have to add in that the little girl in the book grew up to become a particle physicist, a politician and an opera singer, as well as “a mother,” because let’s remind our children that a person can be very well rounded), so I was delighted to see their latest collaboration, The Everywhere Bear. Ticky and Tacky and Jackie the Backie don’t make an appearance, but we’ve got Ollie and Holly and Josie and Jay, Leo and Theo and April and May, etc. etc. All members of a classroom whose class bear comes along with the children on various adventures, but then one weekend things go amiss the bear gets lost, embarking on a remarkable journey of his home that will bring him home again. “Hooray! Hooray!” cheer my children at the end of books like these. “Nobody dies!” They will not tolerate an unhappy ending—even the paper dolls’ snipped up fate makes them a bit uneasy, but we all love this one, Donaldson’s bouncy rhyme and Cobb’s adorable round faces. A keeper for sure.

March 29, 2017

I love love love Workin’ Moms

Much like a certain recent US presidential candidate you may recall, the CBC television series Workin’ Moms is not a perfect candidate. There are some obligatory awkward Canadian production moments (Dan Ackroyd notwithstanding; his casting was brilliant); mild implausibility (how do the workin’ moms manage to fit a mommy’s group into their workdays?); and wardrobe decisions I didn’t blink at but that drove my actual workin’ mom friends berserk—apparently sleeves in the office are pretty much de riguere? Who knew. But over the first season of the show it’s become clear to me that perfection was never what the shows creators were striving for. They put a wandering kodiak bear in the pilot, for heaven’s sake. And it was that bear, or rather character Kate’s response to it, that had me hooked, her serious, furious primal scream. In that powerful moment we were witnessing a mother being born.

The show’s frequent comparisons to HBO’s Girls are not amiss in that neither is a series about women in general, which keeps tripping viewers up “because we’re still more comfortable seeing women as universal types rather than distinct individuals.” If women in general get this treatment, then mothers get it doubly, and the creators of Workin’ Moms are actively working against those expectations of who mothers are and what they should be. In fact, they’re working against all expectations, hence the kodiak bear.

From the start, here is what I loved about the series: first, that the characters aren’t foils. They’re people. That they aren’t having existential crises about matters most people really do manage to work out in reality if not on TV—like, “Oh my god, can I be a mom AND a person?” “Is it okay that I really like my job more than I like taking care of my baby?” “Is it simply inexcusable to admit that I find devoting my entire self to motherhood is more than a bit unfulfilling?” I mean, these are questions the characters in the show are working through, but it’s the process that matters—it’s not as though entire plot points hang upon them. I also like that the workin’ moms’ partners (who are dads, but for one exception) are generally decent human beings. Making dads look dumb is really stupid comedy, and this show is much too smart for that.

I knew I loved the show in the first episode when Frankie started fantasizing about being hit by a bus. She doesn’t want to die, she explains, but how she’d love to go into a coma for eight weeks or so. Later we see her with her head stuck under water in the house she’s showing for a sale. Soon after, she kinda sorta slips under water in the bathtub with her baby daughter—only just caught by her partner. She’s fallen asleep, she claims. A tiny slip. Enough to make the viewer very uncomfortable, which the series never fears to do.

Another character whose trajectory messed me up was Jenny, who headed back to her IT job reluctantly while her husband embraced his time as a stay-at-home dad, and thereby became completely unappealing to her, sexually and otherwise. She starts having weird fantasies about her nerdy manager, and leaving provocative messages on his Facebook page. Alienated from her roles as mother and wife, she starts acting out in outlandish ways, most memorably on the girls’ night out when she demands someone pierce her nipple, which squirts milk at the moment of laceration. Predictably, the nipple gets infected.

I loved Anne, who’s struggling with her older daughter (oh my gosh, when she starts wondering if there’s a slut gene and she’s passed it onto her) and a young baby when she realizes she’s pregnant again. This accidental pregnancy does not come as good news, and she struggles with facing it in her characteristically blunt style—”You’re angrier than usual, Anne,” the leader of the mommies group remarks to her. The group in general in general is a bit put off by the fact that Anne keeps bringing up that she’s considering an abortion. Which is kind of sacrilege in a room full of babies.

And then yes, the abortion. It’s long been a complaint of mine not just that abortions aren’t shown on TV very often, but particularly that nobody ever gets to make jokes about them. (I actually have a long term aspiration to become an abortion humorist.) Workin’ Moms going against the grain again as Anne’s friend Kate (who’s played by show creator Catherine Reitman) cracks this one as she’s driving Anne to a clinic and they’re considering whether you’d Yelp an abortion clinic based on ratings or proximity. Ratings, definitely, Kate figures, and then she takes it further: “I wonder what kinds of complaints an abortion clinic gets? One star. Still pregnant.”

And Kate, my favourite. All life in the city—she’s glorying in the beauty of the day in the park with her son as a vagrants’ pissing against a tree. Sardonic, bad-assed and unapologetic—particularly about her lack of sleeves. Her story throughout the series involves her return to work at a PR firm where she’s firmly established as successful, but she finds she has to redefine her professional role at work now that she’s a mother. Further, she’s a candidate for a prestigious position in Montreal, which would involve leaving her husband and son for three months. Is this something she’s willing to partake in for professional success? (Spoiler: in Tuesday’s episode we see her glorying in her clean white bed, alone, a full night’s sleep, and not a single soul to breastfeed. As any mother knows, there’s not drug in the world as incredible as solitude—but it’s also possible to get too much of a good thing.)

At the beginning of the show in January, Workin’ Moms received a terrible review from John Doyle in the Globe and Mail who chastised the show for its characters’ entitlement. “Oddly, to me, Workin’ Moms celebrates what was mocked with deft scorn by the Baroness Von Sketch series and the Canadian comedy Sunnyside. So, whose side are we supposed to be on? If it’s these appallingly smug people, heaven help us all.” But what the review only proves is that John Doyle doesn’t get it—it’s never been about sides. And what’s remarkable about Baroness Von Sketch and Workin’ Moms alike is that nobody is pitted against no one. Not unless, of course, there’s a very good reason…

In her celebration of Baroness Von Sketch, Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer writes of how the show “celebrates and spoofs the mundane realities in which modern, urban women find themselves depicted. And oh, how the Baronesses know the contours of the boxes in which we live. They have it mapped out like diligent and transgressive draughtswomen who, instead of yielding to the airtight edges of their inherited designs, work to erase them.” And I would argue that Workin’ Moms is a similar kind of project. More subtly though—this isn’t sketch comedy after all. And because it isn’t, the show has to develop in-depth female characters with sustained narratives, and some people hate that. Remember that flawed candidate I started this post with?

Workin’ Moms isn’t perfect, but it never wanted to be—which is the reason it manages to be transgressive, hilarious and discomforting all at once. And it doesn’t fucking care if you don’t like it, which is why I loved it.

The series finale airs next week, but you can watch the whole thing online.

March 29, 2017

Talking Canada Reads on the Radio

Today I got to talk about my favourite Canada Reads contenders from days of yore on CBC Ontario Morning. If you missed me on the radio, you can listen again on the podcast. I come in at 41.00.

March 28, 2017

Mitzi Bytes in the World this Week

This week the “Mitzi Bytes in the world” distinction is literal. As per the photos below, Mitzi has been to Moscow, Paris, Jamaica, and Disney World. I have it on good authority that she makes for good poolside reading—and thank you to everybody who’s sharing their photos. The week’s big excitement was an appearance on Global TV’s morning show, which was as delightful as the clip makes it seem. I got to talk about blogging’s epistolary roots on television, and they asked questions about Harriet the Spy. It was amazing. This week, Mitzi Bytes was also the featured read on The Savvy Reader, which came with this serious endorsement. I love it. And I got to attend Blue Heron Books‘ Books and Brunch Series on Sunday, which apparently was the most raucous event they’ve ever had. So glad to be part of the raucous—we had so much fun.

This week, things are a bit quiet, but I’m looking forward to reading at the Pivot Reading Series on April 5 and then attending GritLit in Hamilton on April 8, where I will be participating in a panel with Merilyn Simonds on in the afternoon and teaching a blogging workshop at 5pm. It’s going to be great.

March 27, 2017

Barrelling Forward, by Eva Crocker

I can’t help it, I need to read a short story collection like a novel. By “like a novel” I mean “like a book,” compelled to keep turning the pages. While I admire those who can dip in and out of a collection, read a story at a time, I’ve come to accept that in general, I’m never going to be that guy. If we’re speaking in terms of appetites and birds, when it comes to books I’m a raven. Which means I appreciate a short story collection like Eva Crocker’s debut, Barrelling Forward, whose momentum is suggested by its title.

I can’t help it, I need to read a short story collection like a novel. By “like a novel” I mean “like a book,” compelled to keep turning the pages. While I admire those who can dip in and out of a collection, read a story at a time, I’ve come to accept that in general, I’m never going to be that guy. If we’re speaking in terms of appetites and birds, when it comes to books I’m a raven. Which means I appreciate a short story collection like Eva Crocker’s debut, Barrelling Forward, whose momentum is suggested by its title.

The first story is “Dealing With Infestation” about a young teacher whose apartment is freezing and infested with something that’s left him itchy with a rash, when he embarks upon an ill-advised foray with his gym-teacher colleague. In “Auditioning,” a set of teenage twins are trying to get gigs acting in commercials, and one must resort to desperate measures to register her distaste with the whole exercise. In “Full-Body Experience,” an exercise instructor tries to get over the death of her sorta-boyfriend in a car accident. “Serving” is from the perspective of a father (middle-age man who works as a server in a family restaurant) and his teenage son, about the father’s innocent (?) relationship with a co-worker, and his colonoscopy. Work and family similarly intertwine in “All Set Up,” about a young father who waffles between contentment with his domestic situation and yearning for more. In “The Landlord,” a young waitress pushes the line about how far she’d go in order to avoid being evicted from her apartment. “Lucky Ones” is a tale of lottery tickets and Sherry, who’s taking care of her boyfriend’s baby while he works the night shift.

Eva Crocker’s stories of work and family life are reflective of modern realities, but underlined by more traditional notions of breadwinning and family structure, her characters are getting stuck in the gaps between these, sometimes perilously. All of these characters are gambling something, still hoping their ship will come in, which keeps the stories buoyant instead of bleak. And while not all the stories are equally successful, and this will be the kind of book that will frustrate you if you’re the type who disdains short stories for ending too soon, it’s a debut that positively sparkles with talent. Here’s hoping Crocker’s career achieves similar momentum as well.

March 24, 2017

Town is by the Sea, by Joanne Schwartz and Sydney Smith

Never has a book so literally sparkled like Town is by the Sea, a new collaboration by Joanne Schwartz and Sydney Smith. In the story, Schwartz draws on her own Cape Breton background to tell the story of a day in the life of a coal mining town, about the life that goes on up above while the men are working down below.

And in a book about contrasts, illustrator Smith pulls off a similar feat. As his early books (reissues of Sheree Fitch’s classics are where we first saw his work!) were fun and cartoonish, that same sensibility charges many of the images in this book—illustrations of domestic life and children at play. (He also exhibits a fixation on teacups that won this book a firm place in my heart.) But the teacups aren’t all of it—just wait for a moment.

Because first we see the men going down into the mines to work. (My children are fascinated by this. “What is coal?” Iris asks us, which is weird because usually she manages to parse out meanings, is rarely moved to ask about something so explicitly.)

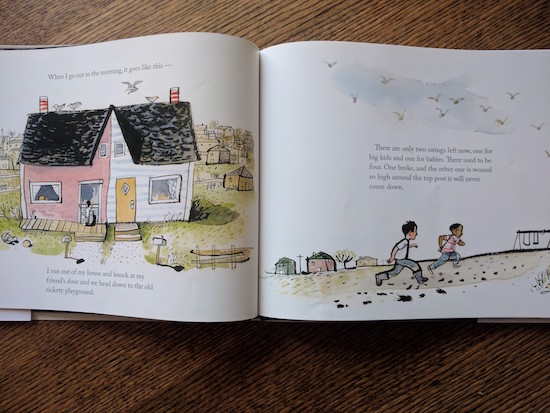

“When I wake up, it goes like this—” Schwartz’s story starts, and this pattern sets up the way that the boy in the book will tell his story. First he hears seagulls, and then a dog barks. “And along the road, lupines and Queen Anne’s lace rustle in the wind…”

“And deep down under that sea, my father is digging for coal.”

And now here it is, that sea. A sea so sparkling that it appears animated, an image that would not look out of place in a museum. Hasn’t it got a bit of the Monet about it? Otherworldly. Which is fitting.

Meanwhile, the boy plays with his friends, he walks through town. He goes home for lunch, then goes back out again. The sea is perpetually present, and its evocation brings us back to the men in the mines. “And deep down under that sea, my father is digging for coal,” and my children read along with the refrain. But the last time we see the men, something is different.

The text doesn’t allude to the image of the men escaping some kind of collapse underground, and the sing-song story goes along, but what happens next in the illustrations takes on a particular subtext, a wordless story like the one Smith tells in JonArno Lawson’s award-winning Sidewalk Flowers*. The boy goes to visit his grandfather’s gravestone, his grandfather who was a miner just like his father, and who made sure that he’d be buried facing the sea because he’d spent enough time underground. “I go to the graveyard to visit my grandfather, my father’s father. He was a miner too. The air smells like salt. I can taste it on my tongue.”

The trouble underground and the imagery of death will make for some uneasy for reading for those of us who know the dangers of coal mining, who’ve heard the stories of disasters. But alas, that is a story for another day. In this book, the boy’s father comes home. Danger and peril, and it’s still just an ordinary day.

“One day it will be my turn,” the boy tells us, about the men who go down below to mine for coal. “I’m a miner’s son. In my town, that’s the way it goes.”

*Full credit goes to my husband Stuart who is much better at reading picture books than I am. It took me ages to figure out that the bear had eaten the rabbit in I Want My Hat Back, or what was different at the end of Sam and Dave Dig a Hole. I might have read this book a hundred more times without realize the enormity of what’s really going on beneath the surface (see what I did there?) so I am glad that I keep someone very clever around.

March 23, 2017

The Mother of All Questions, by Rebecca Solnit

“There is no good answer to how to be a woman; the art may instead lie in how we refuse the question.” —Rebecca Solnit, The Mother of All Questions

Do you remember where you were when you discovered Rebecca Solnit? I do—I was listening to The Sunday Edition on CBC and she was talking about her book, The Faraway Nearby, a book that had a line of prose running throughout the bottom of every page. I read The Faraway Nearby, and fell in love with it, writing this effusive response. This was in 2013. In 2013, we still didn’t know that the world would fall apart and that I’d come to rely on Rebecca Solnit so much to put the pieces back together.

Solnit started particularly steeping in the zeitgeist with her 2012 essay “Men Explain Things to Me,” which lead to the term “mansplaining” although she’s far too elegant a writer to have invented it. The essay was part of a collection of the same name on feminism that was published in 2014, which was the same year that many of the essays in her latest, The Mother of All Questions, were written. “I’ve been waiting all my life forget what 2014 has brought,” her essay, “An Insurrectionary Year” begins, about that “watershed year” in which conversations about rape and sexual violence started changing. It seems like a long time ago now.

There is a Rebecca Solnit book for every moment—and sometimes for two of them. Her collection of essays Hope in the Dark was first published 2004 in light of George Bush’s re-election and the American invasion in Iraq in spite of global demonstrations for peace the likes of which had never been seen before. After the 2016 US election, the book was reprinted and I read it with such gratitude—it gave me comfort. I was reading it as we marched on January 21, and it made me feel buoyant for the first time in months. It indeed brought me hope, and perspective. There have been hard times before, activism is always a process, it’s always too soon to go home, and that you never know what effects your actions will achieve. There are grounds for hope. It’s a reason to bother.

The Mother of All Questions is another book about feminism, although it reads less triumphantly than such a book might have a short time ago. Before the patriarchy saw fit to elect an incompetent sexual predator to its highest office, because the alternative was a smart and qualified woman who rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. They sure showed her though, and all of us, where we’re at in terms of gender politics and equality. It is true that with the elections all my illusions about feminism and progress went kaput, and I’ve been functioning in a state of perpetual heartbreak ever since then. To think I’ve been raising my daughters to have a voice and to take for granted that their ideas and input would be valued by the world—what was I even thinking?

The ideas Solnit takes on here involve silences: “Being unable to tell your story is a living death and sometimes a literal one.” She writes about the people who weren’t permitted to speak, and the tales that weren’t allowed to be told. She writes about the men who are silenced by patriarchal forces, from being themselves, telling their own stories. She writes about rape, consent, domestic violence. She writes about the silence that occurs because no one is listening. About new and difficult conversations that have started to happen in the last twenty years or so, attempts to reconcile the unreconcilable (and the backlash). Most of these essays have appeared elsewhere and I’ve read a few of them, but it does me good to read them here assembled all together. There are many ways that I process the world, but reading Rebecca Solnit is a very important one of them. It’s true, I don’t read for her interrogation. I read her for comfort. Wanting comfort is not such a terrible thing.

However. “All your faves are problematic,” somebody tweeted last week, possibly in response to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s comments about transwomen. And it’s true, and Adichie’s comments were ignorant and she’s not the spokesperson for every single living thing, but I’m not sure there is anybody who isn’t problematic. Remember the year we had to keep quiet about our admiration for presidential candidate Hillary Clinton because she too had failed to be perfect? And I went along with that. It was a silence. To admit one’s lack of socialist principles, and her Iraq war vote. She was the establishment, and there was Wall Street. She wasn’t even cool. Similarly, I had go to keep my excitement about Caitlin Moran’s new book on the downlow because she was racist and ignorant in a tweet in 2011. Which was problematic. But everybody is problematic. (It also seems that there is nothing more problematic than a woman being popular. Or in particular being popular with other woman. If too many women like you, then you’ve suddenly lost all your cred.)

I think we need to give women the space to be problematic though. I think we have let our feminist heroes cause trouble, and be wrong, and not even to atone if they don’t want to. We need to let people complicate things. We need to let others rail against it. That’s how progress happens. That’s how truth emerges. Uncertainty is okay, containers are porous. And I keep returning to the quote I started this essay with, “There is no good answer to how to be a woman; the art may instead lie in how we refuse the question.” Rebecca Solnit keeps refusing it admirably.