September 5, 2017

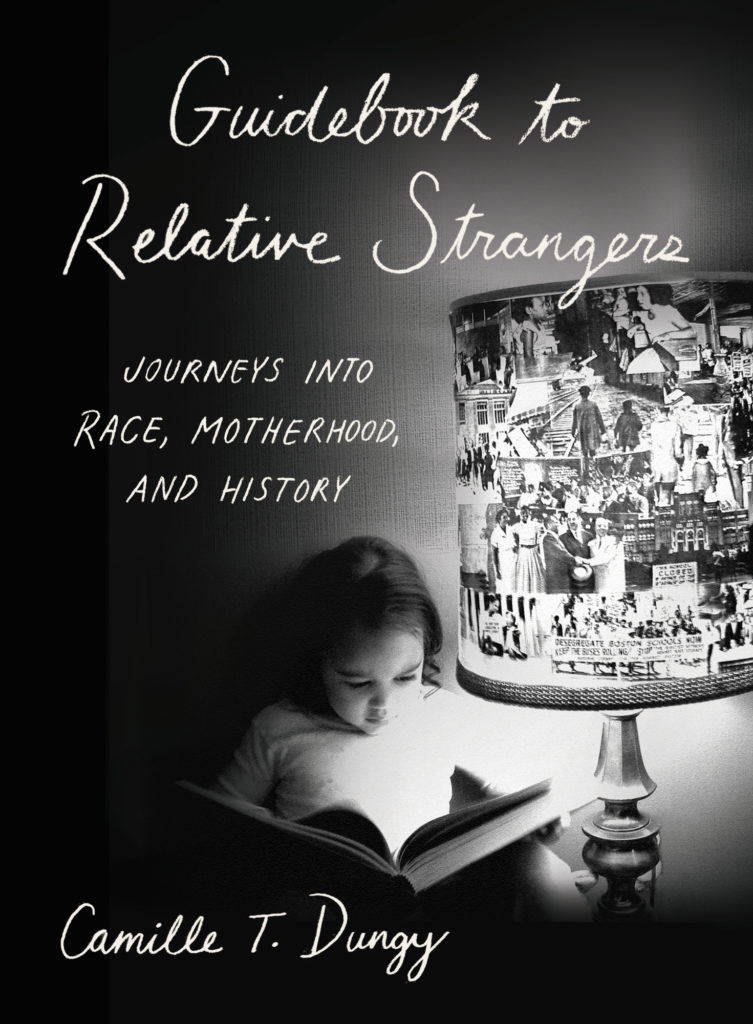

Guidebook to Relative Strangers, by Camille T. Dungy

I can’t remember the last time a book had so strong a hold on me as Camille T. Dungy’s Guidebook to Relative Strangers: Journeys Into Race, Motherhood and History. A book whose force is evident from its opening page, a note of introduction. “When the nation that became the United States was beginning, women writers and black writers needed the endorsement of other people in order to prove their legitimacy,” Dungy writes in her very first sentence. Later in the paragraph: “The essays in the book you are reading are steeped in such history.” Dungy wants to resist this notion that she requires anyone but herself to demonstrate the merit of her work, and yet… She then she goes on to write five pages of the most beautifully written acknowledgements I’ve ever encountered in a book. A remarkable start, and an introduction indeed to Dungy’s expansiveness, generosity, thoughtfulness and ability to understand that two opposing ideas can be true at once.

Guidebook is a collection of essays, but like the best of such things is a journey itself, a whole worth more than its parts which fit so well that they don’t even seem like parts. It begins with an event from Dungy’s not so long-ago past, except that it was a thousand years ago because it was before she became a mother. She was at a writers’ retreat and trying not to become involved in a conversation about how she hadn’t seen the film, The Hours, because she didn’t care about The Hours. In this moment, as is often the case on this retreat, Dungy is the only black person at the table, and is therefore called upon to represent blackness and otherness to the white writers in her company. Which makes her tired—she’s just returned from time in Ghana and the essay contrasts these two experiences and she writes, “Perhaps it would be a more stable world if everyone could experience both the sensation of oneness and otherness a few times in life.” Back at the table, Dungy is assured that her companion doesn’t see her “as a black woman. You’re just who you are.” Which brings the author around to the powerful paragraph that led me to pick up this book in the first place, and certainly the paragraph delivers on everything this paragraph promises:

I am certainly who I am (an ornery individual at the moment) though I take umbrage at the idea of limiting my scope with a word like just when it is used to suggest that I am a simple person. If I may borrow a phrase from the great poet of our early democracy, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” Just in this context erases various complexities and dimensions of my being. There is a danger in refusing to, or tacitly agreeing not to, recognize my black womanness. Black womanness is part of what makes me the unique individual that I am. To claim you do not recognize that aspect of my personhood and insist, instead, that you see me as a “regular” person suggests that in order to see me as regular some parts of my identity must be nullified. Namely, the parts that aren’t like you.

Dungy is a professor, award-winning poet and editor, and devouring her non-fiction (I read this book in a day) put me in mind of Rebecca Solnit and Joan Didion (for style reasons and also San Francisco and California) and Anne Enright’s Making Babies with the perfect exuberance with which she writes about motherhood, and Leslie Jamison for the ways she writes about her body and her experiences with MS. Most of all, however, Dungy writes about language, which itself reveals so many secrets and much complexity. The essay “Bounds” is an incredible consideration of that words many meanings and what their connections tell us about human experience, about Dungy’s daughter’s language acquisition, about what divides us and what connects us, and how so often these two things are one and the same. I ordered this book not long after the terrifying events in Charlottesville, VA, in August, and it’s something to consider the images from the white supremacist rally against Dungy’s short essay about her time living in Virginia where her white friends delighted in bonfires, and she, because of the area’s legacy of racial violence, could only feel fear at the idea and reality of these kinds of events.

Dungy writes about her experiences travelling in America before her daughter turned two, when she was still nursing and could fly on her mother’s lap for free, and about the places they went and how Dungy would be both connected to and divided from the people she encountered, and how her daughter helped to mitigate the distance between Dungy and others. This is a book about the labours of motherhood and academia, and writing, and the ridiculous ways we negotiate these in the 21st century. It’s a book about cities and nature, and the words we use to describe these places, the names we call ourselves and others, and the places motherhood takes us where we never planned on going—I love a line in the essay “Inherent Risk, Or What I Know About Investment” that goes, “I passed the sign for the landmark every time I took the Fruitvale Avenue exist off I-580 on my way home, but I had no idea what it referred to until one day, when Callie still cried constantly unless she was moving, I strapped her into the stroller and walked until I found the place, which is how I started to know some of the things I’ve written here.”

The essay “Bodies of Evidence,” about birdwatching with her two friends who are two of the five black birders in America, so the joke goes; about her daughter’s infatuation with The Little Mermaid; about her own family’s legacy of racial violence; about Dungy spending her adult life trying to delay the onset of the diabetes that plagues her family, only to be diagnosed with MS; “When I am writing, it is always about history. What else could I be writing about? History is the synthesis of our lives;” about being the only person in her second-grade class who voted from Jimmy Carter in a 1980 mock-election; about a visit to a memorial of a lynching that took place in Duluth, Minnesota; about survival, be it through MS or poison oak—or a police officer pulling you over on a dark highway, if one happens to be black; about an article in the New Yorker about inequality, about an eclipse, about shadow. This is one essay. “Sometimes it is easy to draw meaning from the arbitrary order of things.” But of course there is nothing arbitrary about any of this—these essays are masterful. Buy this book now.

August 31, 2017

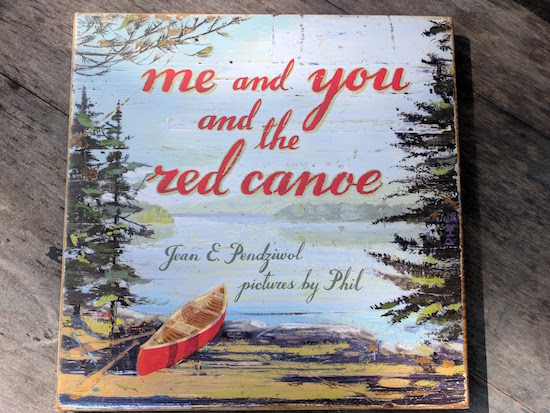

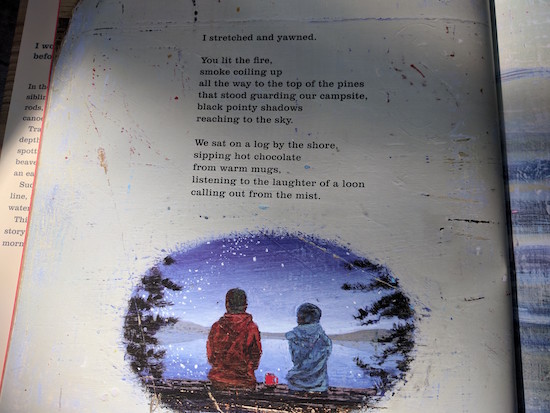

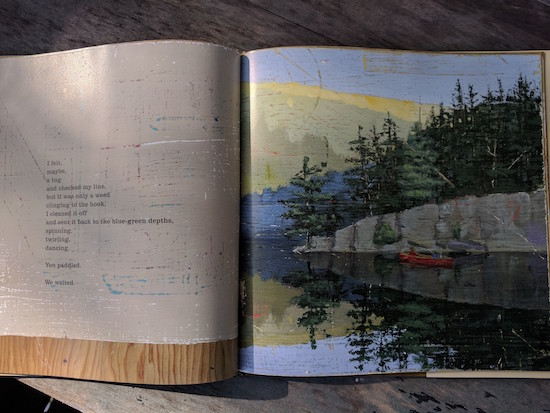

Me and You and the Red Canoe, by Jean E. Pendziwol and Phil

“We’re going to have to shut the windows,” I called out a few minutes ago. I’d gone outside to take photos for this blog post, and they’re possibly a bit blurry because I was shivering. There are only a few hours left of August, and tonight the temperature is supposed to go down to 7 degrees. Summer has ebbed, though there is still a long weekend left, and tomorrow we’re taking the ferry to the Toronto Islands and intend to play on the beach, even if it’s a little bit freezing and it might all be a bit English seaside. But we like the English seaside, and it seems a fitting way to spend the last day of summer holidays—beside the water, feet in the sand. We’ve had that kind of summer.

We are not big canoeists. Once in the Lake District, my husband and I rented a rowboat, and I ended up screaming at him as he steered us into a dock full of tourists, and it wasn’t very romantic. So we’ve been a bit wary of nautical vessels ever since then, unless they’re inflatable flamingos, which we’re all over. Literally. But still, Me and You and the Red Canoe, by Jean E. Pendziwol and illustrated by Phil, has been a book that (lucky us!) so suits our summer. We’ve had loons and campfires, and empty beaches, and quiet mornings, and twinkling stars and soaring eagles in the sky. Would be that our children could paddle away from us early morning, and return with fish that somebody in our family would know how to prepare. Imagine if anyone knew how to use a paddle…but still. We went kayaking when we were away in July, and it was pretty lovely. Nobody yelled at anyone.

The illustrations in this book are beautiful, seemingly painted on wood, with lots of texture, a lovely roughness, and glimpses of under layers. They’re timeless, nostalgic in an interesting way, and a lovely complement to Pendziwol’s lyrical story, which is so rich in sensory detail and focused in the perfect notes. There’s not a lot of specificity—who are the siblings telling the story? When does it take place? Was this long ago or yesterday? When the siblings woke early and went out early to catch the fish that would be remembered as the best breakfast ever. Observing lots of wildlife, flora and fauna, and quiet and beauty on the way—it’s all the best things about summer, for those of us who are lucky enough to be able to get away from it all. Even if we don’t know how to canoe.

(PS We did visit the Canadian Canoe Museum last week, however! That’s the next best thing to actually paddling a canoe, right?)

August 30, 2017

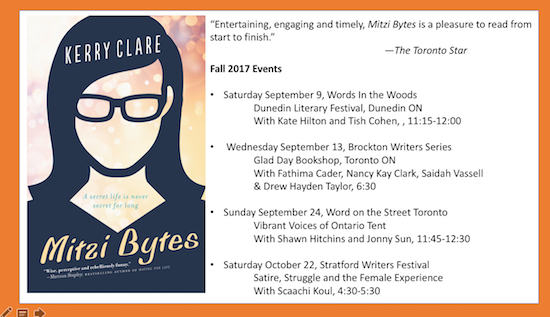

Mitzi Bytes: Coming Up

I am looking forward to a busy fall with Mitzi Bytes things, with two events in Toronto (including Word on the Street!) and trips to Dunedin and Stratford. At Brockton Writers on September 13, I’ll be giving a short talk about my experience of how I got from blog to book. And I’ve got book club visits scheduled too—very excited about these. Do let me know if you’d like me to visit your book club—email me at kerryclare AT gmail DOT com.

In other Mitzi Bytes news, my interview with Shelagh Rogers was rebroadcast last week (during the eclipse, even!) and that was fun. I was super happy that my #MitziInTheSun summer prize pack found an excellent home. Thanks to everybody who participated. And I’m grateful for this wonderful review by Heidi Darroch; one paragraph begins, “Like Maria Semple or Meg Wolitzer…” so I pretty much have everything I ever wanted.

August 27, 2017

All Time Record

I made a very uncharacteristic vow a few months ago to only bring a couple of books on vacation, and not be so maniacally compelled to be always reading. Because I remember feeling pressure to read on previous vacations, which is stupid for a vacation and also made me anti-social…and then I ended up bringing seven books on vacation, plus a few extras, for Stuart to read and for just-in-case scenarios. But I decided I didn’t have to finish them all during our week at the lake. What better way to retain that holiday feeling than to let the holiday reading continue over into the week we’re back home, I thought. There was no pressure. I was going away with a towering stack, but I didn’t have to read all of them.

But then I did! Without being anti-social, even, because I also swam in the lake, played UNO and charades and Old Maid and Zingo. But on top of this, I lingered in bed in the mornings, read by flashlight at night after everyone was asleep, and got lots of reading in while the children were out chasing frogs, treasure hunting, or partaking in nighttime movies every evening at 7pm in the rec hall. There was time enough for all the reading, but also for all the other things. The days were so perfectly elastic, the way summer days are meant to be.

There was no rhyme nor reason to my stack of holiday books, except for the first, which was The Burning Girl, by Claire Messud, because I had to get it read for work reasons. But it turned out to be perfect, because it was such a summer book, steeped in atmosphere and there was a quarry and everything. Such a strange, skewed book too though, like everything Messud writes. It’s a look back on a friendship between two girls which breaks off at the point in which girlhood breaks off into womanhood, and the whole story delivered with this spectacular dose of nostalgia—except the main events of the narrative are just two years before and the narrator is still a teenager. I wasn’t expecting that, and it was kind of disorienting, this idea of the 1990s being something that happened “before I was born.” I’m used to young protagonists being set in the past. It was interesting. And she was such an interesting protagonist too, elusive and tricky in the way of Messud’s from The Women Upstairs. (Remember the furor from that book, about women and likability, and then Jennifer Weiner got involved?) This book is more subtle though, so much so that it needs an additional read to puzzle out its construction. The “Bev Burnes” character continues to haunt me, with her ample backside. And yes, the quarry. It would turn out that nearly all my holiday books would take place around bodies of water. Isn’t it funny the way that a syllabus assumes itself?

There was no rhyme nor reason to my stack of holiday books, except for the first, which was The Burning Girl, by Claire Messud, because I had to get it read for work reasons. But it turned out to be perfect, because it was such a summer book, steeped in atmosphere and there was a quarry and everything. Such a strange, skewed book too though, like everything Messud writes. It’s a look back on a friendship between two girls which breaks off at the point in which girlhood breaks off into womanhood, and the whole story delivered with this spectacular dose of nostalgia—except the main events of the narrative are just two years before and the narrator is still a teenager. I wasn’t expecting that, and it was kind of disorienting, this idea of the 1990s being something that happened “before I was born.” I’m used to young protagonists being set in the past. It was interesting. And she was such an interesting protagonist too, elusive and tricky in the way of Messud’s from The Women Upstairs. (Remember the furor from that book, about women and likability, and then Jennifer Weiner got involved?) This book is more subtle though, so much so that it needs an additional read to puzzle out its construction. The “Bev Burnes” character continues to haunt me, with her ample backside. And yes, the quarry. It would turn out that nearly all my holiday books would take place around bodies of water. Isn’t it funny the way that a syllabus assumes itself?

From this point on my reading also became a fun celebration of all the bookshops I’ve been visiting this spring and summer. I picked up Turning, by Jessica J. Lee at Curiosity House Books when we were in Creemore in June, a book I was partial to for #SwimLit reasons and also because of Lindsay’s review at her swimming hole blog. Once again, a book focussed on a body of water, or in this case many of them—although this time I’d seen it coming. The memoir is Lee’s story of her lifelong complicated relationship with swimming and water, and also with notions of identity and home, and about how she got over a bout of heartache and depression by spending a year swimming in lakes near her home in Berlin. A year indeed, which means Lee swims in all kinds of weather, in the deepest winter with a hammer to break the ice, and in the winter she never swims for too long. Although apparently the more you winter swim, your body grows accustomed to lower temperatures—though I’m going to just take her word for it. (I must say that Lee inspired me to jump into the lake wholeheartedly every day and not be a slow entering ninny. If she can swim in December, I can just in during August.) I liked the book a lot, and found it strange and disorienting in a fascinating way, the way a foreign city first appears, kind of. It was unusual to be reading about Germany and Berlin because all my frames of reference for swimming are so Canadian and English—it occurs to me that I know nothing about German geography at all, and little more about its literature. There is so much still to be immersed it, but Lee’s memoir was a memorable dip.

From this point on my reading also became a fun celebration of all the bookshops I’ve been visiting this spring and summer. I picked up Turning, by Jessica J. Lee at Curiosity House Books when we were in Creemore in June, a book I was partial to for #SwimLit reasons and also because of Lindsay’s review at her swimming hole blog. Once again, a book focussed on a body of water, or in this case many of them—although this time I’d seen it coming. The memoir is Lee’s story of her lifelong complicated relationship with swimming and water, and also with notions of identity and home, and about how she got over a bout of heartache and depression by spending a year swimming in lakes near her home in Berlin. A year indeed, which means Lee swims in all kinds of weather, in the deepest winter with a hammer to break the ice, and in the winter she never swims for too long. Although apparently the more you winter swim, your body grows accustomed to lower temperatures—though I’m going to just take her word for it. (I must say that Lee inspired me to jump into the lake wholeheartedly every day and not be a slow entering ninny. If she can swim in December, I can just in during August.) I liked the book a lot, and found it strange and disorienting in a fascinating way, the way a foreign city first appears, kind of. It was unusual to be reading about Germany and Berlin because all my frames of reference for swimming are so Canadian and English—it occurs to me that I know nothing about German geography at all, and little more about its literature. There is so much still to be immersed it, but Lee’s memoir was a memorable dip.

Next I read Do Not Become Alarmed, by Maile Maloy (also from Curiosity House Books in Creemore), whom I’d never read before, but I purchased the novel after reading Ann Patchett’s endorsement. In her back-of-the-book blurb, Patchett writes that this is the kind of novel you will barrel through and then should go back and re-read to realize how technically brilliant it is. Not quite sure I’ll be doing the latter, but this is a 300+page book that I read in less than a day. Also about a body of water, this one being an alligator-infested river in Panama in which a group of American children are floating in inner-tubes when they drift away from their errant parents. The American children are on a cruise with their families and they’ve just embarked from an excursion, and it’s all gone a bit wrong, and it’s only going to get worse. The story is indeed fast-paced and enthralling, and there were a few moments where the prose and what was happening took my breath away. This is a book about privilege, naivety, stupidity, and the ways in which Americans (and their ilk—hi! [waves]) are able to go about their lives protected from the risks and dangers that are commonplace in so many other countries.

Next I read Do Not Become Alarmed, by Maile Maloy (also from Curiosity House Books in Creemore), whom I’d never read before, but I purchased the novel after reading Ann Patchett’s endorsement. In her back-of-the-book blurb, Patchett writes that this is the kind of novel you will barrel through and then should go back and re-read to realize how technically brilliant it is. Not quite sure I’ll be doing the latter, but this is a 300+page book that I read in less than a day. Also about a body of water, this one being an alligator-infested river in Panama in which a group of American children are floating in inner-tubes when they drift away from their errant parents. The American children are on a cruise with their families and they’ve just embarked from an excursion, and it’s all gone a bit wrong, and it’s only going to get worse. The story is indeed fast-paced and enthralling, and there were a few moments where the prose and what was happening took my breath away. This is a book about privilege, naivety, stupidity, and the ways in which Americans (and their ilk—hi! [waves]) are able to go about their lives protected from the risks and dangers that are commonplace in so many other countries.

Next up was Weaving Water, by Annamarie Beckel, which was a book I’d been interested in for Annie Dillard Tinker Creek reasons, and then picked up to read after I met Annamarie at the Lakefield Literary Festival. In this book, the body of water in question is a pond in Newfoundland—and the novel points out that “ponds” in Newfoundland can often be the size of large lakes. On the banks of the pond is an old cabin that belonged to Beth Meyer’s husband’s great-aunt, who left it to them after she died. An ecologist by training and on the cusp of a new stage in life now that her daughter has gone away to school, Beth moves out to the remote cabin to do research on river otters, looking for answers to save an earth in peril. She meets her eccentric neighbour with an unshakable belief in ghosts and magic, and her neighbour’s nephew who Beth is drawn to in spite of herself. It turns out the answers Beth is looking for are not just about river otters after all, but the creatures remain at the centre of the novel and Beckel’s wonder at their habits and mysteries are absolutely palpable.

Next up was Weaving Water, by Annamarie Beckel, which was a book I’d been interested in for Annie Dillard Tinker Creek reasons, and then picked up to read after I met Annamarie at the Lakefield Literary Festival. In this book, the body of water in question is a pond in Newfoundland—and the novel points out that “ponds” in Newfoundland can often be the size of large lakes. On the banks of the pond is an old cabin that belonged to Beth Meyer’s husband’s great-aunt, who left it to them after she died. An ecologist by training and on the cusp of a new stage in life now that her daughter has gone away to school, Beth moves out to the remote cabin to do research on river otters, looking for answers to save an earth in peril. She meets her eccentric neighbour with an unshakable belief in ghosts and magic, and her neighbour’s nephew who Beth is drawn to in spite of herself. It turns out the answers Beth is looking for are not just about river otters after all, but the creatures remain at the centre of the novel and Beckel’s wonder at their habits and mysteries are absolutely palpable.

It took me a while to know that Emily Fridlund’s A History of Wolves (which I bought at Lighthouse Books in Brighton the weekend we were camping) would really work. There’s something off-putting about it, and it takes time to realize that that off-puttingness is part of its very design. Ostensibly, it fits right in with all the other books, with the body of water even—the lake the narrator lives on with her parents at their abandoned commune, isolated in the woods of northern Minnesota. But then a couple moves into a new cabin across the lake, and she can watches them through their windows, and begins to care for their young son. And she’s drawn to the family in a way that’s connected with a former teacher who was eventually charged with possession of child p*rnography, and a classmate who’d been connected to him. How do all the pieces fit together? To be honest, I’m still not entirely sure and it’s the kind of book I should return to and I’m even compelled to, but am not sure I will. Because of the off-puttingness, a narrator who never really connects to anyone. Again, which is the point, and there’s a killer last line that underlines this point. I ended up really appreciating this book, though I can’t say I liked it. But in the end, it was a perfect fit with all the rest, the splash of the paddle from Linda’s canoe as she makes her way across the lake.

It took me a while to know that Emily Fridlund’s A History of Wolves (which I bought at Lighthouse Books in Brighton the weekend we were camping) would really work. There’s something off-putting about it, and it takes time to realize that that off-puttingness is part of its very design. Ostensibly, it fits right in with all the other books, with the body of water even—the lake the narrator lives on with her parents at their abandoned commune, isolated in the woods of northern Minnesota. But then a couple moves into a new cabin across the lake, and she can watches them through their windows, and begins to care for their young son. And she’s drawn to the family in a way that’s connected with a former teacher who was eventually charged with possession of child p*rnography, and a classmate who’d been connected to him. How do all the pieces fit together? To be honest, I’m still not entirely sure and it’s the kind of book I should return to and I’m even compelled to, but am not sure I will. Because of the off-puttingness, a narrator who never really connects to anyone. Again, which is the point, and there’s a killer last line that underlines this point. I ended up really appreciating this book, though I can’t say I liked it. But in the end, it was a perfect fit with all the rest, the splash of the paddle from Linda’s canoe as she makes her way across the lake.

I wasn’t sure how Scarborough, by Catherine Hernandez (which I bought on our trip to Mabel’s Fables a few weeks back), would fit in with all the rest, a book that is so urban. But then it turned out to have its own body of water, the Rouge River, and the book opens with a heron at the river’s mouth, and it moves through the seasons in the same way Lee’s Turning did. I loved this novel, which had been recommended by loads of people and which I read in less than a day. At the centre of the story is a drop-in centre at a Scarborough elementary school where families turn up for company, support…and breakfast. We see the program coordinator’s communications with her supervisor and the way that bureaucratic requirements (and racism) keep the program from properly serving the people it’s meant to. There are failings and there is tragedy, but there is also resilience and connection. Scarborough has just been nominated for a Toronto Book Award and I’m thrilled about that.

I wasn’t sure how Scarborough, by Catherine Hernandez (which I bought on our trip to Mabel’s Fables a few weeks back), would fit in with all the rest, a book that is so urban. But then it turned out to have its own body of water, the Rouge River, and the book opens with a heron at the river’s mouth, and it moves through the seasons in the same way Lee’s Turning did. I loved this novel, which had been recommended by loads of people and which I read in less than a day. At the centre of the story is a drop-in centre at a Scarborough elementary school where families turn up for company, support…and breakfast. We see the program coordinator’s communications with her supervisor and the way that bureaucratic requirements (and racism) keep the program from properly serving the people it’s meant to. There are failings and there is tragedy, but there is also resilience and connection. Scarborough has just been nominated for a Toronto Book Award and I’m thrilled about that.

Next up was Lianne Moriarty’s Truly Madly Guilty, which I bought at Beggar’s Banquet Books in Gananoque when I was there in early May. I loved her Big Little Lies back in March, and remember hearing about this one when it came out last year but then didn’t read it after coming across a dismissive review—I think there was a big reveal that was meant to be anti-climatic in the end. But I’m so glad I finally picked it up. Moriarty is brilliant, and will never get the literary credit she deserves for sexist reasons. Indeed, this is a novel that revolves around a mystery—something happened at a bbq and the novel moves between the perspectives of different characters reflecting on the events leading up to it. At the centre of the book is two friends, Clementine and Erica, friends since childhood with a complicated dynamic. And Moriarty gets it so perfectly, the way that a friendship can come with ambivalence and animosity, and she ties it to the women’s marriages and their relationships to their mothers. The reviewer is correct that the big reveal is less than we’ve been lead to believe it’s going to be—but it doesn’t matter because the point of the book turns out to be so much bigger than what happened one night. And that’s what’s so fantastic about it, the hugeness of this novel’s scope—this event of one night ends up connecting to stories that are decades old and to characters far-flung and nearby. It reminded me of The Slap, by Christian Tsiolkas, but without the violence and misogyny. Moriarty manages to show every single character at their worst, but redeem them too in a way that’s entirely believable. And now I want to read every single thing she’s ever written. (PS: this was the one that didn’t quite click with all the others, but then there ended up being a body of water after all, which was a very tacky backyard fountain that meets with a sorry end.)

Next up was Lianne Moriarty’s Truly Madly Guilty, which I bought at Beggar’s Banquet Books in Gananoque when I was there in early May. I loved her Big Little Lies back in March, and remember hearing about this one when it came out last year but then didn’t read it after coming across a dismissive review—I think there was a big reveal that was meant to be anti-climatic in the end. But I’m so glad I finally picked it up. Moriarty is brilliant, and will never get the literary credit she deserves for sexist reasons. Indeed, this is a novel that revolves around a mystery—something happened at a bbq and the novel moves between the perspectives of different characters reflecting on the events leading up to it. At the centre of the book is two friends, Clementine and Erica, friends since childhood with a complicated dynamic. And Moriarty gets it so perfectly, the way that a friendship can come with ambivalence and animosity, and she ties it to the women’s marriages and their relationships to their mothers. The reviewer is correct that the big reveal is less than we’ve been lead to believe it’s going to be—but it doesn’t matter because the point of the book turns out to be so much bigger than what happened one night. And that’s what’s so fantastic about it, the hugeness of this novel’s scope—this event of one night ends up connecting to stories that are decades old and to characters far-flung and nearby. It reminded me of The Slap, by Christian Tsiolkas, but without the violence and misogyny. Moriarty manages to show every single character at their worst, but redeem them too in a way that’s entirely believable. And now I want to read every single thing she’s ever written. (PS: this was the one that didn’t quite click with all the others, but then there ended up being a body of water after all, which was a very tacky backyard fountain that meets with a sorry end.)

And next up to another woman writer who doesn’t get the credit for being as brilliant as she is, and that’s Laura Lippman—although she gets some credit. I’ve loved her work for years now, and was happy to read Wilde Lake, which I bought at Happenstance Books when I was there for the Lakefield Literary Festival. Stuart had already read it and couldn’t wait for me to finally get to it so we could talk about it. Loosely an homage to To Kill a Mockingbird, it’s about a newly elected State Attorney in Howard County, Maryland, who’s following in her revered father’s footsteps. When Lu’s first big murder case surprisingly hearkens back to events during the summer of 1980 during which her big-shot brother was involved in an altercation where somebody turned up dead, all kinds of long-forgotten secrets are brought up to the surface. This is a novel about rape culture, and the ways in which changes in the law have influenced how rapes are prosecuted, and it’s about fallibility, family secrets, and lost ideals, and I thought about it for days and days afterwards. It’s full of twists and surprises, and the most evocatively depicted small town, built around a lake, of course. It’s really an extraordinarily good novel.

And next up to another woman writer who doesn’t get the credit for being as brilliant as she is, and that’s Laura Lippman—although she gets some credit. I’ve loved her work for years now, and was happy to read Wilde Lake, which I bought at Happenstance Books when I was there for the Lakefield Literary Festival. Stuart had already read it and couldn’t wait for me to finally get to it so we could talk about it. Loosely an homage to To Kill a Mockingbird, it’s about a newly elected State Attorney in Howard County, Maryland, who’s following in her revered father’s footsteps. When Lu’s first big murder case surprisingly hearkens back to events during the summer of 1980 during which her big-shot brother was involved in an altercation where somebody turned up dead, all kinds of long-forgotten secrets are brought up to the surface. This is a novel about rape culture, and the ways in which changes in the law have influenced how rapes are prosecuted, and it’s about fallibility, family secrets, and lost ideals, and I thought about it for days and days afterwards. It’s full of twists and surprises, and the most evocatively depicted small town, built around a lake, of course. It’s really an extraordinarily good novel.

And then it was Friday and we were heading home the next day and the other book we’d bought was Bear Town, but Stuart was in the middle of it. And so I went to check out the library at the resort we were staying at, and was pleased to discover The Murder Stone, by Louise Penny (which was the UK title, published in Canada as A Rule Against Murder), which I haven’t read yet. (I came to Penny’s Three Pines series late with A Trick of the Light.) It was absolutely perfect to read because it was set at a place much like the place where were staying (albeit much much more fancy!) and as I was reading the part in the book where there was a huge storm with thunder and lightning, we were having the exact same weather and the lightning kept illuminating our little cabin just like daylight, and it was all a little too close to home.

And then it was Friday and we were heading home the next day and the other book we’d bought was Bear Town, but Stuart was in the middle of it. And so I went to check out the library at the resort we were staying at, and was pleased to discover The Murder Stone, by Louise Penny (which was the UK title, published in Canada as A Rule Against Murder), which I haven’t read yet. (I came to Penny’s Three Pines series late with A Trick of the Light.) It was absolutely perfect to read because it was set at a place much like the place where were staying (albeit much much more fancy!) and as I was reading the part in the book where there was a huge storm with thunder and lightning, we were having the exact same weather and the lightning kept illuminating our little cabin just like daylight, and it was all a little too close to home.

August 3, 2017

The Summer Book

I finished The Summer Book this other night, an anthology of non-fiction from BC writers that has proven such a delight and travelled me all the way from June to the end of July. The collection opens with Theresa Kishkan’s stunning essay, “Love Song,” which you can read here, an essay that articulates the magic of summer and all its strange tricks of time and light. I also loved pieces by Eve Joseph (“My memories of summer have as much to do with longing as they do with summer itself….”), Fiona Tinwei Lam on her childhood home and her family’s backyard pool, and other stories of summer love, summer cusps (see Sarah de Leeuw on the summer that began the end of childhood) and summer heartache. Luanne Armstrong’s Summer Break which so perfectly articulates the awful fleetingness of summertime: “I am caught between the beach and the future, between time and no time…” She writes about “how to cope or understand or even live with the world in such a state of frightening fragmentation where there is both the paradisial beach and the black muck of ‘news.'” And goes on, “Fortunately for me, the mountains and lake don’t care… Every day, I walk on the mountains, down to the beach, up through the trees, watching, noticing.” It’s summertime, and the living is complicated. But a book like this gives its reader a similar effect.

August 2, 2017

Annie Muktuk and Other Stories, by Norma Dunning

When I read the article, “What inspired her was getting mad,” about the story behind Norma Dunning’s debut collection, Annie Mukluk and Other Stories, I was not surprised. Acts of justice and revenge factor throughout the book, propelling the stories so terrifically. Dunning wrote her stories in response to ethnographic representations of Inuit people that neglected to show them as actual people, and the result is a book that’s really extraordinary. Because her people are so real, people who laugh, and joke, and drink, and have sex (and they have a lot of sex). Her characters love each other fiercely, family ties are nurtured in spite of obstacles (including residential schools and their legacy) and they all have a great deal of fun playing with the ignorance of the qallunaaq (Anglo-Canadian) and their perceptions of the north.

When I read the article, “What inspired her was getting mad,” about the story behind Norma Dunning’s debut collection, Annie Mukluk and Other Stories, I was not surprised. Acts of justice and revenge factor throughout the book, propelling the stories so terrifically. Dunning wrote her stories in response to ethnographic representations of Inuit people that neglected to show them as actual people, and the result is a book that’s really extraordinary. Because her people are so real, people who laugh, and joke, and drink, and have sex (and they have a lot of sex). Her characters love each other fiercely, family ties are nurtured in spite of obstacles (including residential schools and their legacy) and they all have a great deal of fun playing with the ignorance of the qallunaaq (Anglo-Canadian) and their perceptions of the north.

In “The Road Show Eskimo,” an elderly Inuit woman who found fame as the apparent author of a book about her experiences in the South—except the book was a fraud and it had been written by her white ex-husband—makes money from this endeavour and she even relishes the role she has to play to conform to peoples’ expectations. But on the particular day depicted in this story, the woman is going to take back her identity and use the power she’s been holding all along.

Such power also factors in the story “Husky,” about a HBC Agent who brings his three Inuit wives to Winnipeg where they are all made victims of violent racism—until they aren’t anymore, and the women take matters into their hands in the most fantastic feat of justice.

I loved “Elipsee,” about a man who’s taking his beloved wife out on the land one more time—she’s dying of cancer and this is the one thing left to try, and it actually works, in a beautiful, sad and perfect way, as the couple reconnects with their own history and that of their ancestors. In “Kakoot,” an Inuit man at the end of his life tries to leave this world for the next, which is complicated when you life in an old age home in the south and the spirit of your land and people are hard to come by.

And “Annie Muktuk” is the gorgeous story of two friends, one of whom has fallen in love with the titular character, described as follows:

“What I couldn’t get into Moses Henry’s head was that she just wasn’t Annie Mukluk. She was bipolar. She liked the Arctic and the Antarctic. She played with penguins and the polar bears. Annie Mukluk liked to fuck and she did it with everyone in Igloolik and everywhere else she went. She’d fuck your father, your sister, all your brothers and finish off with your mother. She swung both ways and sideways.”

(This paragraph joins the one about Slutty Marie from Megan Gail Coles’ Eating Habits… as perhaps two of my favourite paragraphs about women with voracious sexual appetites in all of Canadian literature.)

Anyway, the two friends, Moses Henry and Johnny Cochrane are each puzzling out the ways forward in their lives, in a fantastic, ferocious and bawdy novella about love, and brotherhood and friendship. I loved it. In “My Sisters and I,” three amazing women survive their experiences at residential school with their wits and strength, and the punch in the nose at the end of the story is the spectacular and perfectly delivered act of violence. This is justice, which is nice to encounter somewhere, even fictionally, because there’s certainly not much of it in reality. But these kinds of representations of Inuit women are just the beginning…

August 2, 2017

Other Words, Other Summers

On my CBC Ontario Morning column this morning, my theme was other worlds and other summers, spectacular transporting books you might have missed the first time around which are so timeless that it will never be too late to go back to them. Like this weekend, maybe? You can listen again on the podcast here. I come in at 38.4 minutes.

August 1, 2017

Camping With Louise Penny

I have developed a hammock habit over the last few years, and most lazy summer afternoons you’ll find me in my urban backyard enjoying a warm breeze and basking in the shade of our enormous silver maple. Reading, obviously. And the best thing about a hammock habit is that it can be altogether portable if you’ve got the right hammock, which I do, complete with a foldable frame and a carrying bag. It is the heaviest most awkward portable object imaginable, but it’s mine, and it’s the most essential item in our mountain of equipment when we’re packing the car to go camping.

We’re not natural campers, my family. I’m a bad Canadian and my husband is an immigrant, and so camping (along with ice skating) is an activity we’ve had to work hard to fall in love with—mostly for the sake of the children. But because camping doesn’t involve falling all over perilous slippery surfaces while wearing blades on our shoes, we’ve actually had some luck with this. This summer will be our fourth year pitching a tent out in the wilderness—or rather, more realistically, while my husband is busy pitching the tent, I’ll be setting up my hammock.

The hammock itself is not the only ingredient necessary for a successful camping weekend, however. We need bug spray, and sleeping pads, fire-starters and marshmallows, and we need books. And not just any books. For me, I’ve learned that a weekend camping in the woods is not completely unless I’ve got a big fat Louise Penny novel to be absorbed in. The hammock would be wasted without it.

Miles from the cozy civilization invoked by the fictional Three Pines, with its bistro, B&B, boulangerie and bookshop, I spend our camping afternoons in my hammock wholly wrapt by Penny’s novels, compelled by her character, Chief Inspector Armand Gamache and his call to duty. There will be some sort of crime, either immediately or eventually a murder, and any gruesomeness related to this matter will be abated by the scenes Penny sets in Three Pines, a place as familiar to me as my own neighbourhood is. I pick up these books in anticipation of returning to Three Pines, and to its people, who are complicated, irreverent, brilliant, warm and funny. And there, in the middle of the woods in Ontario, insects buzzing about and sunshine peeking in through the canopy of tall skinny pine trees, there I’ll be.

You can almost smell the croissants warm from the oven, which is saying something, when a fictional redolence can overpower the actual smell of outhouse.

(We had an amazing, albeit bug-infested, camping trip this weekend. Lucky me, I had an ARC of Louise Penny’s new novel Glass Houses in hand. You can see more photos on my Instagram.)

July 27, 2017

Feast: An Edible Road Trip

If might surprise some people to find that I have blogging advice beyond “Blog like nobody’s reading (because often nobody is)” but if you’ve been reading carefully you will also know that I’m a firm believer that a blog needs room to grow and space to wander. And Lindsay Anderson and Dana VanVeller must have known this too when they began their blogging endeavour a few years ago because they gave themselves an entire nation to wander through. Their blog was called An Edible Road Trip and chronicled their adventures (and misadventures) eating across Canada to discover a culinary culture “beyond Kraft Dinner, poutine, Nanaimo Bars, and butter tarts.”

One of the highlights of my spring and book promotion has been travelling to (and eating in!) different places I haven’t spent much time in before. My blueberry scone at the Hamilton Farmers’ Market was legendary, and then the mind-blowing dinner we had in Waterloo as part of the Appetite for Reading Book Club. And it was in Gananoque at the 1000 Islands Writers Festival where I met up with the women behind Feast, the book that grew out of the edible road trip. The book was already on my radar because of the story behind it and also its beautiful design (and you can read their very cool blog post, “Anatomy of a Cookbook Cover”, here). And then I got to listen to their amazing presentation about their journey across Canada and the people they met and the things they learned about—the farmer in the Yukon whose farm you need to travel to via two canoe rides was one anecdote that surprised me and stuck in my mind. Naturally, I bought the book—and their event was spectacularly catered with local farmers’ market fare and the whole thing was totally delicious. Feast, I figured, would be an excellent souvenir.

The whole idea behind it was a little bit abstract though, practically speaking. It was May by this point and therefore rhubarb season and I proceeded to bake the Lunar Rhubarb Cake (pictured above) at least three times before June. The recipe doesn’t skimp on sugar, and it won rave reviews at every table at which I served it… But still. A nice cookbook to have, but I wasn’t sure how often I was going to use it. And then we went away for a week in Nova Scotia…

And then suddenly a whole bunch of recipes that had merely existed on the page for me before meant something altogether different. Upon coming home, I reread the Nova Scotia page and recognized all kinds of references and was reminded of the very good places we ate on our trip.

The first thing I made upon homecoming wasn’t from Nova Scotia at all, however, but instead the Sour Cherry Pierogi recipe from the prairies. I found sour cherries at a local green grocer and it sounded so delicious, and so I made them (with help from Stuart who was in charge of construction) and they were SO SO good. And then we got to use the leftover compote for porridge.

And I’d wanted to make the s’mores scones all along for reasons that should be altogether self-explanatory, but the mission took on a sense of urgency when I reread the recipe and learned it was from the chef at Two If By Sea, whose croissants were so delectable on our trip that we went to Dartmouth twice. So baking these scones was a little bit like a homecoming, even if for a place that wasn’t our home at all—but the food made it all so familiar.

Which is why we made the seafood chowder the following Friday, even though chowder isn’t always the best thing you can be eating when it’s 36 degrees celsius, but we weren’t sorry. I’d got fresh fish at the grocery store that morning and even though it wasn’t the fresh fish we’d become accustomed to (Stuart ate scallops in Lunenberg that he might never get over—in a good way) it was incredibly delicious and made us miss Nova Scotia a little less. And we’ve still got the oatcakes to make, and a few other Atlantic items to try.

And then after that? Well, between the book and our trip, we’ve never been so inspired to and travel to another new part of the country. And in the meantime we’ll be cooking from Feast because Canada is delicious.