September 19, 2017

You can’t synthesize this

I’m of two minds. I usually am. I don’t know that’s such a bad thing, and the thing my brain gets up to when I’m swimming lengths or walking down the street is looking for synthesis. You can change the world and be the change to wish to see in it at once, I mean; I can “find ways to fight all of the systems that uphold my privilege while simultaneously standing up for myself when I am pushed down”; I’ve always thought that gender is a construct and mine doesn’t define me, but transgender people exist and so they should; I abhor violence, but want to punch everyone I see on a Segway; I love my children and I’m so grateful for my abortion. Etc. Etc. Yes, but, Yes, and. And in my head I’m always trying to put all the pieces together, to demonstrate that really we’re all on the same page. A grand unification theory, as it were. But a thing I’m learning as I get older is that while everything is complicated, everything is so complicated that we’re never to agree on just how. The tension is inherent to the project. It’s even often useful. And it’s never going to go away.

I wrote a piece for CBC online last week about our family’s choice to rent a home instead of buy one, and I was nervous about this project. I kept thinking about the furor surrounding the Toronto Life “We Bought a Crackhouse” family, all that entitlement. And here I am, a privileged person writing about our choices and our freedoms as a result of where and how we live, when for many people affordable housing is rare to the point where it’s a crisis. But that turned out not to be the problem at all. And for a day or so there was no problem, until the piece was featured on the CBC’s main page and got a lot of attention, inciting comments on social media and on the piece itself—and they were ridiculous. Not about my failure to address income inequality and poverty (although that might have called for a longer article) but for the very point my piece addressed—that not buying into the cult of real estate makes other people go berserk. Not since the days when my peers debated sleep-training strategies on Facebook have I ever waded into anything so controversial—though naturally, I was of two minds about the sleep issue. I’m even of two minds about real estate, really—if buying a house were remotely in our means and didn’t require huge compromises in our lifestyle, I’d be all for it. I would love to have a house that was my own—although I wouldn’t be able to buy any furniture for it.

There is something about saying, “I’m going to have it all the ways,” that makes other people really angry. I notice this when I argue about abortion online—someone will always accuse a woman who has an abortion of being selfish. There is this needlessly puritanical fixation on sacrifice and selflessness, the idea that making a decision with one’s own happiness in mind is somehow suspect. When really, it just seems sensible to me. If you are lucky, you get to make the choice to do the thing you want to do—and how could you ever fault someone for doing so? But a lot of people do. And not just for something as controversial as abortion either, an argument whose “other side” I have some sympathy for (never mind the fact that you have to railroad over the lives of actual living breathing women to make it, and if you have no discomfort with this then you just might be a misogynist). But also for something as seemingly innocuous as real estate. Seriously, does anything ever provoke ire like a woman who declares to say in public, “I made a choice that makes me happy and I am satisfied”?

You can’t synthesize this. There is no thesis. There is only hysterical emotion and anger. People read my piece on renting and they really really cared what I said, and they really really thought I was wrong, so much so that they logged onto public forums to say so. None of this is a surprise to anybody who’s ever said anything online, but it’s the most read I’ve ever been as a writer, I think. It’s also the first time I’ve ever written anything that was of any interest in general to men. And this was interesting, although women were represented among the outraged. Fortunately, conversation was pretty cordial, and no one called me fat, or threatened to rape me, which means it was a good day on the internet. (Obviously, those two kinds of comments are barely comparable, except that they are the standard go-tos for people online who have feelings about something a woman has said on the internet.) Fortunately, also, the outrage in reposes to my piece was pretty darn funny and I got a lot of amusement out of it, and (shockingly) none of the financial arguments managed to convince me that our choice is the wrong one. The choice we’ve spent a lot of time thinking about and built our lives around. It’s just fascinating, that anybody cared so much. And very sad about that one man whose comment was, “I’m never going to buy your book.” Oh no! How will I make it through?

You can’t synthesize this. There is no thesis. There is only hysterical emotion and anger. People read my piece on renting and they really really cared what I said, and they really really thought I was wrong, so much so that they logged onto public forums to say so. None of this is a surprise to anybody who’s ever said anything online, but it’s the most read I’ve ever been as a writer, I think. It’s also the first time I’ve ever written anything that was of any interest in general to men. And this was interesting, although women were represented among the outraged. Fortunately, conversation was pretty cordial, and no one called me fat, or threatened to rape me, which means it was a good day on the internet. (Obviously, those two kinds of comments are barely comparable, except that they are the standard go-tos for people online who have feelings about something a woman has said on the internet.) Fortunately, also, the outrage in reposes to my piece was pretty darn funny and I got a lot of amusement out of it, and (shockingly) none of the financial arguments managed to convince me that our choice is the wrong one. The choice we’ve spent a lot of time thinking about and built our lives around. It’s just fascinating, that anybody cared so much. And very sad about that one man whose comment was, “I’m never going to buy your book.” Oh no! How will I make it through?

Some things are not worth synthesizing. “The cult of real estate in Canada is so pervasive that I’d never before questioned whether buying a house would be our next step in adulthood,” I wrote in my piece, and the cult of real estate keeps trying to pervade. Which makes pieces like mine necessary, I think, not in spite of the way they provoke stupid outrage, but because they do. That’s my thesis, and I’m sticking to it.

September 19, 2017

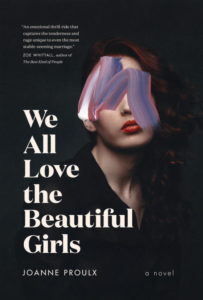

We All Love the Beautiful Girls, by Joanne Proulx

A thing I think is funny is a description in Joanne Proulx’s biography accompanying her recently released second novel, We All Love the Beautiful Girls. Among much acclaim for her previous novel is the detail that it won “Canada’s Sunburst Award for Fantastic Fiction,” which would be a cool award to be win, I imagine. To be officially fantastic. Although the tag for the Sunburst Award is “for excellence in the Canadian literature of the fantastic.” Which is to say genre, sci-fi and fantasy. Which is to say that Proulx, whose previous book was the YA title Anthem of a Reluctant Prophet, as an author requires tricks to be packaged, wrapped up tidily in a neat little box for her mainstream novel about the perils of modern family life.

A thing I think is funny is a description in Joanne Proulx’s biography accompanying her recently released second novel, We All Love the Beautiful Girls. Among much acclaim for her previous novel is the detail that it won “Canada’s Sunburst Award for Fantastic Fiction,” which would be a cool award to be win, I imagine. To be officially fantastic. Although the tag for the Sunburst Award is “for excellence in the Canadian literature of the fantastic.” Which is to say genre, sci-fi and fantasy. Which is to say that Proulx, whose previous book was the YA title Anthem of a Reluctant Prophet, as an author requires tricks to be packaged, wrapped up tidily in a neat little box for her mainstream novel about the perils of modern family life.

And this is makes We All Love the Beautiful Girls so interesting, I think. Fantastic, even, in the non-supernatural sense of the word. It makes the novel not wrapped up or tidy or boxy in the slightest, instead furious with momentum, bursting open, exploding at seams.

I read the second half of this novel in a few hours one Saturday night, because it was a story that just kept going and going. Although I wasn’t sure at the very beginning, when all the action gets out of the way in a chapter or two: Michael and Mia discover they’ve been bilked out of their life-savings by a business partner/friend, and then their son, Finn, passes out in the snow at a party, nearly dying, with injuries he’ll carry with him for the rest of his life. All of this within the first 50 pages of a book over 300 pages long—what else can happen? Oh, only everything, and it’s how Proulx frames this narrative that is so fascinating, not on the drama itself but on unintended consequences, the shocking, tragic and terrifying ways that one thing can lead to another.

This is a novel with sharp edges and tight corners, and it’s a novel not afraid to make its reader uncomfortable. Told from Michael and Mia’s points of view in third-person and Finn’s in first person, the narrative is fragmented, patchwork, and then all the pieces become drawn together in the most disturbing fashion. And then it dawns on the reader as it dawns on the characters, that all these things are connected—objectification of and/or violence against women in particular, and how each and every character is implicated, and we see that that two characters peripheral to the story—Jess, a former babysitter now college student who sneaks in Finn’s window to sleep with him; Frankie, Finn’s contemporary whose feelings for him aren’t returned—and Mia herself are not so far apart after all in their experiences of womanhood and what is required for survival.

Some of the very worst things are what turn out to be universal.

September 18, 2017

Finally!

My children started school two weeks ago, but they didn’t really, because Iris’s first day wasn’t until Thursday, and I still had two articles due that week, plus two presentations to prepare for in the week following. So back-to-school as not a breath of fresh air and return to routines, because instead it was a scramble, but I did it. Articles finished, presentations presented, and here I am finally with five full workdays before me with only my usual deadlines, and time for creative work. I am going to revise a short story and write a new one that has been brewing for awhile, and then a new draft of my novel begins and there’s going to be lots of digging. So much work ahead, but I am looking forward to it—discovery is the greatest thing about writing anything. Plus, I have a million books to write about (far too few disappointing reads lately means I’ve overwhelmed with things to tell you about) and I want to write about my trip to Edmonton, so let this post serve as official confirmation: this blog is back in business. And if you’ve sent me an email lately, I will probably reply to it soon.

September 12, 2017

What is Going to Happen Next, by Karen Hofmann

A group of siblings running wild in rural British Columbia, under the dubious care of their hippie dad while their mother has been hospitalized for psychiatric problems. We first glimpse them through the point-of-view of twelve-year-old Cleo who sees herself as the family lynchpin, caring for her younger brothers along with her older sister, Mandalay. Just barely holding it together, and then their father dies. The police are at the door. Cleo is trying to pass herself off a a responsible agent, so earnestly that the reader can almost forget that she is only a child. But she is indeed only a child, and her baby brother will be adopted, Cleo and her brothers placed in foster care, Mandalay in a group home. Each of the siblings set in very different orbits…and the novel actually begins twenty years on from all that.

A group of siblings running wild in rural British Columbia, under the dubious care of their hippie dad while their mother has been hospitalized for psychiatric problems. We first glimpse them through the point-of-view of twelve-year-old Cleo who sees herself as the family lynchpin, caring for her younger brothers along with her older sister, Mandalay. Just barely holding it together, and then their father dies. The police are at the door. Cleo is trying to pass herself off a a responsible agent, so earnestly that the reader can almost forget that she is only a child. But she is indeed only a child, and her baby brother will be adopted, Cleo and her brothers placed in foster care, Mandalay in a group home. Each of the siblings set in very different orbits…and the novel actually begins twenty years on from all that.

Cleo is a middle-class mother of two small children, overwhelmed by the excruciating demands of early motherhood and hungry for intellectual stimulation. Hofmann so exactly captures the claustrophobic impossibility of life with small children, and all the details that can trip one up—navigating strollers through rough terrain, the preparation and work required for a trip on the bus. The loneliness too, and this is only added to as the unnavigability of the world with small children keeps Cleo close to home. That she has no example in her own past of functional family life leaves Cleo even more stranded than the average mother of young children. Her husband is not without sympathy, but he’s frustrated, and not receptive to what his wife is going through.

Meanwhile, Cleo’s sister Mandalay is living a different kind of life in the downtown core of Vancouver, far away from the suburbs. We find her at at a particularly high point—the cafe she has been co-managing has just found acclaim by being written up in a magazine. Mandalay loves her job, her co-worker, that she is responsible for arranging art in the place and becoming known for her skills in curation. Sure, her apartment is tiny and expensive, and her work means she is busy all the time, but Mandalay finds herself fulfilled for the first time in her life, after years spent hitching onto the rides of the men she’s been in relationships with. Which, inconveniently, is the moment that Duane turns up, a man who suits her in so many ways but is unwilling to provide proper emotional ties. But does she want these? Does she need these? What kind of relationship does Mandalay think she deserves?

And then finally, there is their younger brother Cliff, hapless, utterly lacking guile. He’s not stupid though, Cliff, and he knows the problem is mainly other people. So he knows, for instance, not to let people know about his new TV, when he finally saves up from his landscaping job for the one he’s been looking for. He knows that when other people find out he’s got something, they’re only ever going to want to take it, so he keeps to himself. He works hard and has made a comfortable life for himself, and all he wants is to stay out of trouble…but trouble seems to find him. And Hofmann’s depiction of Cliff is one of the most wonderful parts of this book, how fully realized he is, without the cliches often fastened to literary characters lacking in IQ. How canny he actually has to be to get along in the world, and all the tricks and devices he’s figured out that nobody would ever give him credit for. He’s a terrific character.

The novel opens with the three siblings’ different narrative threads, each of which are far apart due to family history and how disparate their circumstances are in terms of life and also of postal codes. The three of them are in touch, but mainly see each other at holidays, can go weeks without a phone call. But when their long lost baby brother finally tracks them down, and then Cliff has an accident that requires him to recover in the relative quiet of Cleo’s suburban house, the siblings begin to come together again. And questions are raised not only about the practical matters of how characters who’ve come from different places can be a family, regardless of their mutual place of origin. But also about the role their past traumas play in the present day, and what those traumas are, exactly. It turns out the history each of them has taken for granted turns out to be more complicated than any of them have imagined. And what does that mean for the future?

I really liked Karen Hofmann’s first novel, After Alice, and was so pleased that What is Going to Happen Next lived up to my expectations—and then some. It’s a novel that’s as original as it is ambitious, and it works, resulting in an all-engrossing visceral reading experience, and I’m recommending it to everyone.

September 11, 2017

Happy Half-Birthday, Mitzi Bytes!

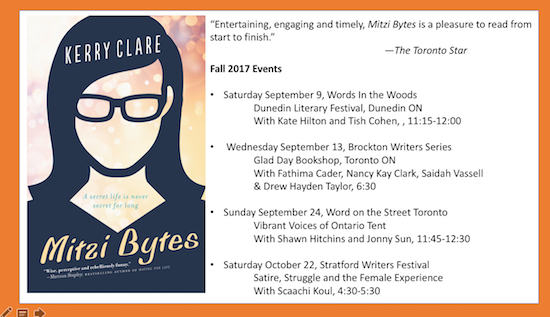

It’s Mitzi Bytes’ half-birthday! This week marks six months since Mitzi was launched and hit the Independent Bestseller list, reaching #2 for Trade Paperback Fiction and #6 Overall. It’s been an excellent run, and we’ve celebrated by finally making use of our custom cookie cutters from our friends at Jammy Dodger, The Bakery. I am grateful to everybody who has supported this book, booksellers, festivals, friends and readers. You’ve made this all such a pleasure.

And speaking of pleasures, have never known one quite like the Dunedin Literary Festival. It was the most beautiful, fall colours just beginning to give us glimpses, and the sun was shining and the sky was blue. I appeared on a panel with my friend, Kate Hilton, moderated by Tish Cohen, whose Town House I read and loved ten years ago. We had such a good time, and afterwards I hung out with my husband and children and we soaked up all the goodness of a day out in nature—there were activities for kids, a playground and swing, delicious local fare for lunch (empanadas to die for), and I got to see the panel later that day with Alison Pick, Cecily Ross, and Claire Cameron. It was a wonderful day, and I’m really looking forward to returning in 2018.

There are more good things coming up this week! I’m doing a talk on the (long and winding) road from blog to book at the Brockton Writers this Wednesday at the Glad Day Bookshop. And Word on the Street is next week, Sunday September 24. In conjunction with WOTS, I got to do a fun questionnaire with She Does the City answering questions about my writing life and readerly fixations. You can read it here.

September 8, 2017

Buddy and Earl Go to School, by Maureen Fergus and Carey Sookoocheff

I love September—cardigans, golden light and sharpened pencils—but I also hate September. I always did. Because I hate change, although I’ve been trying hard not to let my children catch onto this. And while I loved the possibility of fresh starts, clean slates and pristine pencil cases, there was always an adjustment. New classes, new friends, old friends who had become new people, new teachers—I would find these things very difficult. I still do. My children seem to be doing perfectly fine, but I have had a difficult week adjusting to grade three and junior kindergarten—who would have thought it? All the tumult and violence going on in the world hasn’t helped the matter either.

And so I’ve sought solace in good things, sweet things and funny things. Buddy and Earl Go To School, by Maureen Fergus and Carey Sookoocheff is the fourth book in this series about a dog and a hedgehog and (although I think I’ve said this about previous titles, but still) it’s the best one yet! I can’t say what it is we like so much about these books at our house exactly, except that it involves the fact of a hedgehog, plus Buddy the dog’s deadpan address and aversion to contractions. It is understated, adorable comic genius.

In this story, Buddy and Earl are starting school. “‘Hurrah!’ cheered Earl. ‘Getting an education is the first step to achieving my dream of becoming a dentist.’ / ‘I do not think think hedgehogs can become dentists, Earl,’ said Buddy./ ‘With the right education, I can become anything,’ declared Earl. ‘And so can you, Buddy.”/ Buddy was very excited to hear this.”

When they turned up at school, the setting defied my expectations but was also so perfectly familiar. The school day proceeds in adorable funny fashion, and even when Earl was bored (“How long until gym? Is it almost snack time?”), we weren’t. And by the end of the book, I’m left with a bit more pep in my step. Every school day can be rich with surprises, and there is promise i September after all.

September 7, 2017

No one updates their blog enough

No one updates their blog enough. But this is okay, because if my complaint was, “Everyone updates their blog too often,” it would tell you something about blogs and how much they matter to me—namely that they don’t. But they do, even though I have not had time to read blogs this summer. A statement that previously would have seemed ridiculous to me because one can always find some time. But this summer I spent less time than usual online, and I’m not sorry about this. But it’s wondrous to come to blogs, today while I eat my lunch, home alone, Iris’s first day of kindergarten. Feeling emotional, obviously, but blogs are such a solace, and I feel like my friends have all been here for me. And I want to share their posts with you.

No one updates their blog enough. But this is okay, because if my complaint was, “Everyone updates their blog too often,” it would tell you something about blogs and how much they matter to me—namely that they don’t. But they do, even though I have not had time to read blogs this summer. A statement that previously would have seemed ridiculous to me because one can always find some time. But this summer I spent less time than usual online, and I’m not sorry about this. But it’s wondrous to come to blogs, today while I eat my lunch, home alone, Iris’s first day of kindergarten. Feeling emotional, obviously, but blogs are such a solace, and I feel like my friends have all been here for me. And I want to share their posts with you.

- Sarah at Edge of Evening who is blogging from the beginning of August, and now I am waiting for her postcard from September, and to hear how her holiday to America was.

- A newer-to-me blog is Summer At Shores, by a woman I met at the Lakefield Literary Festival in July. I want to share her irises post, for obvious reasons, and because it’s wonderful.

- Pip Lincolne writes thoughtfully about a social media pile-on and women’s media at her blog, Meet Me At Mikes.

- I never tire of Julia Zarankin on the extraordinary ordinariness of birding at Birds and Words.

- I can’t wait to read Emily Wight’s new cookbook, Dutch Feast, which promises to make me fat, but in the meantime, there is a wonderful recipe for macaroni to tide me over.

- Rebecca Woolf on her daughter’s amazing, inspiring wildness.

- Alice Zorn on the amazing things that transpire when you publish a novel

- A new post at A Dainty Dish!! Ann Marie took my UofT blogging course a few years ago, and is one of the best people ever, and her new post is delightful and has pie.

- I promise you that Lindy Mechefske’s post is the most emotional, gorgeous recipe for making ricotta from expired milk that you’ve ever encountered in your life.

- Theresa Kishkan has a new book out, Euclid’s Orchard, and here’s a post about the difficult time in which it was created.

- Lindsay sums up a summer with swimming in her usual exuberant way.

- And Matilda Magtree DOES NOT REVIEW Dawn Dumont’s Glass Beads, which was a novel I loved entirely.

I don’t usually end my blog posts with questions, encouraging readers to engage in a more organic fashion, but I’m genuinely curious here, so I’m going to break my rule. What blogs have you been appreciating lately? Any posts you’ve written that you’re particularly proud of?

September 5, 2017

Guidebook to Relative Strangers, by Camille T. Dungy

I can’t remember the last time a book had so strong a hold on me as Camille T. Dungy’s Guidebook to Relative Strangers: Journeys Into Race, Motherhood and History. A book whose force is evident from its opening page, a note of introduction. “When the nation that became the United States was beginning, women writers and black writers needed the endorsement of other people in order to prove their legitimacy,” Dungy writes in her very first sentence. Later in the paragraph: “The essays in the book you are reading are steeped in such history.” Dungy wants to resist this notion that she requires anyone but herself to demonstrate the merit of her work, and yet… She then she goes on to write five pages of the most beautifully written acknowledgements I’ve ever encountered in a book. A remarkable start, and an introduction indeed to Dungy’s expansiveness, generosity, thoughtfulness and ability to understand that two opposing ideas can be true at once.

Guidebook is a collection of essays, but like the best of such things is a journey itself, a whole worth more than its parts which fit so well that they don’t even seem like parts. It begins with an event from Dungy’s not so long-ago past, except that it was a thousand years ago because it was before she became a mother. She was at a writers’ retreat and trying not to become involved in a conversation about how she hadn’t seen the film, The Hours, because she didn’t care about The Hours. In this moment, as is often the case on this retreat, Dungy is the only black person at the table, and is therefore called upon to represent blackness and otherness to the white writers in her company. Which makes her tired—she’s just returned from time in Ghana and the essay contrasts these two experiences and she writes, “Perhaps it would be a more stable world if everyone could experience both the sensation of oneness and otherness a few times in life.” Back at the table, Dungy is assured that her companion doesn’t see her “as a black woman. You’re just who you are.” Which brings the author around to the powerful paragraph that led me to pick up this book in the first place, and certainly the paragraph delivers on everything this paragraph promises:

I am certainly who I am (an ornery individual at the moment) though I take umbrage at the idea of limiting my scope with a word like just when it is used to suggest that I am a simple person. If I may borrow a phrase from the great poet of our early democracy, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” Just in this context erases various complexities and dimensions of my being. There is a danger in refusing to, or tacitly agreeing not to, recognize my black womanness. Black womanness is part of what makes me the unique individual that I am. To claim you do not recognize that aspect of my personhood and insist, instead, that you see me as a “regular” person suggests that in order to see me as regular some parts of my identity must be nullified. Namely, the parts that aren’t like you.

Dungy is a professor, award-winning poet and editor, and devouring her non-fiction (I read this book in a day) put me in mind of Rebecca Solnit and Joan Didion (for style reasons and also San Francisco and California) and Anne Enright’s Making Babies with the perfect exuberance with which she writes about motherhood, and Leslie Jamison for the ways she writes about her body and her experiences with MS. Most of all, however, Dungy writes about language, which itself reveals so many secrets and much complexity. The essay “Bounds” is an incredible consideration of that words many meanings and what their connections tell us about human experience, about Dungy’s daughter’s language acquisition, about what divides us and what connects us, and how so often these two things are one and the same. I ordered this book not long after the terrifying events in Charlottesville, VA, in August, and it’s something to consider the images from the white supremacist rally against Dungy’s short essay about her time living in Virginia where her white friends delighted in bonfires, and she, because of the area’s legacy of racial violence, could only feel fear at the idea and reality of these kinds of events.

Dungy writes about her experiences travelling in America before her daughter turned two, when she was still nursing and could fly on her mother’s lap for free, and about the places they went and how Dungy would be both connected to and divided from the people she encountered, and how her daughter helped to mitigate the distance between Dungy and others. This is a book about the labours of motherhood and academia, and writing, and the ridiculous ways we negotiate these in the 21st century. It’s a book about cities and nature, and the words we use to describe these places, the names we call ourselves and others, and the places motherhood takes us where we never planned on going—I love a line in the essay “Inherent Risk, Or What I Know About Investment” that goes, “I passed the sign for the landmark every time I took the Fruitvale Avenue exist off I-580 on my way home, but I had no idea what it referred to until one day, when Callie still cried constantly unless she was moving, I strapped her into the stroller and walked until I found the place, which is how I started to know some of the things I’ve written here.”

The essay “Bodies of Evidence,” about birdwatching with her two friends who are two of the five black birders in America, so the joke goes; about her daughter’s infatuation with The Little Mermaid; about her own family’s legacy of racial violence; about Dungy spending her adult life trying to delay the onset of the diabetes that plagues her family, only to be diagnosed with MS; “When I am writing, it is always about history. What else could I be writing about? History is the synthesis of our lives;” about being the only person in her second-grade class who voted from Jimmy Carter in a 1980 mock-election; about a visit to a memorial of a lynching that took place in Duluth, Minnesota; about survival, be it through MS or poison oak—or a police officer pulling you over on a dark highway, if one happens to be black; about an article in the New Yorker about inequality, about an eclipse, about shadow. This is one essay. “Sometimes it is easy to draw meaning from the arbitrary order of things.” But of course there is nothing arbitrary about any of this—these essays are masterful. Buy this book now.

August 31, 2017

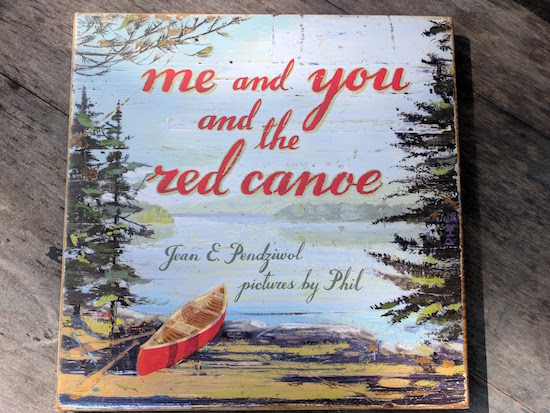

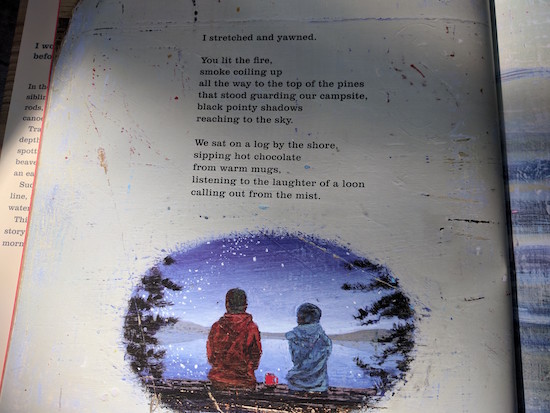

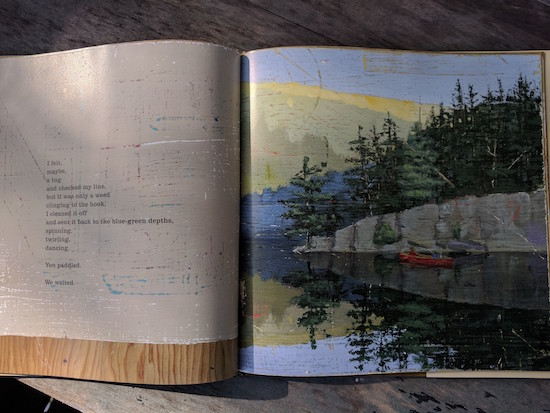

Me and You and the Red Canoe, by Jean E. Pendziwol and Phil

“We’re going to have to shut the windows,” I called out a few minutes ago. I’d gone outside to take photos for this blog post, and they’re possibly a bit blurry because I was shivering. There are only a few hours left of August, and tonight the temperature is supposed to go down to 7 degrees. Summer has ebbed, though there is still a long weekend left, and tomorrow we’re taking the ferry to the Toronto Islands and intend to play on the beach, even if it’s a little bit freezing and it might all be a bit English seaside. But we like the English seaside, and it seems a fitting way to spend the last day of summer holidays—beside the water, feet in the sand. We’ve had that kind of summer.

We are not big canoeists. Once in the Lake District, my husband and I rented a rowboat, and I ended up screaming at him as he steered us into a dock full of tourists, and it wasn’t very romantic. So we’ve been a bit wary of nautical vessels ever since then, unless they’re inflatable flamingos, which we’re all over. Literally. But still, Me and You and the Red Canoe, by Jean E. Pendziwol and illustrated by Phil, has been a book that (lucky us!) so suits our summer. We’ve had loons and campfires, and empty beaches, and quiet mornings, and twinkling stars and soaring eagles in the sky. Would be that our children could paddle away from us early morning, and return with fish that somebody in our family would know how to prepare. Imagine if anyone knew how to use a paddle…but still. We went kayaking when we were away in July, and it was pretty lovely. Nobody yelled at anyone.

The illustrations in this book are beautiful, seemingly painted on wood, with lots of texture, a lovely roughness, and glimpses of under layers. They’re timeless, nostalgic in an interesting way, and a lovely complement to Pendziwol’s lyrical story, which is so rich in sensory detail and focused in the perfect notes. There’s not a lot of specificity—who are the siblings telling the story? When does it take place? Was this long ago or yesterday? When the siblings woke early and went out early to catch the fish that would be remembered as the best breakfast ever. Observing lots of wildlife, flora and fauna, and quiet and beauty on the way—it’s all the best things about summer, for those of us who are lucky enough to be able to get away from it all. Even if we don’t know how to canoe.

(PS We did visit the Canadian Canoe Museum last week, however! That’s the next best thing to actually paddling a canoe, right?)

August 30, 2017

Mitzi Bytes: Coming Up

I am looking forward to a busy fall with Mitzi Bytes things, with two events in Toronto (including Word on the Street!) and trips to Dunedin and Stratford. At Brockton Writers on September 13, I’ll be giving a short talk about my experience of how I got from blog to book. And I’ve got book club visits scheduled too—very excited about these. Do let me know if you’d like me to visit your book club—email me at kerryclare AT gmail DOT com.

In other Mitzi Bytes news, my interview with Shelagh Rogers was rebroadcast last week (during the eclipse, even!) and that was fun. I was super happy that my #MitziInTheSun summer prize pack found an excellent home. Thanks to everybody who participated. And I’m grateful for this wonderful review by Heidi Darroch; one paragraph begins, “Like Maria Semple or Meg Wolitzer…” so I pretty much have everything I ever wanted.