March 27, 2018

Catch My Drift, by Genevieve Scott

I was always going to have an affinity for Genevieve Scott’s debut novel, Catch My Drift. Its protagonist, Cara, is nearly my exact contemporary, and I also have a strong fascination with the 1970s’ Toronto that brought my parents together and delivered us all into the world I remember from my childhood. I’m also kind of crazy about Swim-Lit, although Catch My Drift is only really pool-centric in the first chapter, which is when Cara’s mother Lorna is a on the cusp of trying out for the Varsity swim team at the University of Toronto. It’s 1975, and swimming is her entire identity, her whole life. Which has already been rocked by the end of a romance and a car accident in which her knees were injured, undermining her swimming potential. It’s summer and she’s training at the pool where her roommate is a lifeguard, sneaking in for laps just before closing. But when it comes time to prove herself, Lorna flinches, setting in motion the rest of her life, for better or for worse.

I was always going to have an affinity for Genevieve Scott’s debut novel, Catch My Drift. Its protagonist, Cara, is nearly my exact contemporary, and I also have a strong fascination with the 1970s’ Toronto that brought my parents together and delivered us all into the world I remember from my childhood. I’m also kind of crazy about Swim-Lit, although Catch My Drift is only really pool-centric in the first chapter, which is when Cara’s mother Lorna is a on the cusp of trying out for the Varsity swim team at the University of Toronto. It’s 1975, and swimming is her entire identity, her whole life. Which has already been rocked by the end of a romance and a car accident in which her knees were injured, undermining her swimming potential. It’s summer and she’s training at the pool where her roommate is a lifeguard, sneaking in for laps just before closing. But when it comes time to prove herself, Lorna flinches, setting in motion the rest of her life, for better or for worse.

We meet Cara in the next chapter, 1987, nine-years-old, and see Lorna now, no longer a woman on the cusp of her life, but instead a mom. A mom who’s dealing with an unreliable partner, the domestic demands of parenthood, and the consequences of a life she made that hasn’t turned out like she might have imagined. But all this is on the periphery—the narrative is filtered through the perspective of Cara, for whom her mother doesn’t really exist as a character in her own right yet. And so the story goes, moving back and forth from mother to daughter as the years go on, as Cara develops into her own person and Lorna reconciles with her own choices, a life with a lot she is proud of. Although at this point, we’re still seeing her through the disdainful eyes of her teenage daughter, who is grappling with her own questions about the kind of woman she wants to be, so it’s complicated. But it is the subtle softening of Cara’s understanding of her mother, her own emerging sympathy for her that is my favourite part of the novel, and culminates in an ending I feared would be heartbreaking but ended up being perfect and beautiful.

Not everything is subtle in Catch My Drift. Some secondary characters border on caricature. This is a novel composed of pieces and the shape of it all is a little unwieldy. In some places it reads like a first novel…but the more I read, the more assured I was by the project, and the more the story appealed to me beyond simple nostalgia. Partly because it becomes clear that nostalgia is a point the novel hangs on—what do we remember and why? What version of reality are those memories made of? How did we get from here to there? What are the consequences of our actions, both in our own destinies and in the lives of others? Because the answers are wondrous and far-reaching, even in the most ordinary lives.

March 26, 2018

A One-Handed Novel, by Kim Clark

It’s a quandary, certainly, and not one I’ve ever encountered in fiction before. Melanie Farrell has already done most of the things you read about in novels—she’s come of age, gotten married, been divorced, confronted a life-changing diagnosis (Multiple Sclerosis) etc. etc., but now in Kim Clark’s A One-Handed Novel, her doctor delivers her some devastating news. Her disease is progressing (not news) and a neurological test has revealed she has just six orgasms left. Six! And she’s already spent once since the test, she realizes—what to do? And so begins her journey to use those remaining orgasms to their best and fullest potential, to make each one count. But then best intentions have always been Melanie’s downfall—witness the items on her Twelve Days of Christmas list, which are most consistently “liquor” and “guilt”. With hilarity and so much heart, Clark takes her reader on Melanie’s journey to make the most of her remaining orgasms. A comic novel about MS—who would have thought it? But it’s also about sex, about coming to terms with one’s bodily limitations, and about friendship, money, hope, and community. It’s not so narratively taut—a third of the way through the remaining orgasms conceit is put aside while Melanie travels to Costa Rica for the expensive and controversial “liberation therapy” which fails to deliver the results she is looking for. Clark also relies too much on humour to carry the story, poignant moments rushed by to arrive at a wisecrack. The end of the novel also crosses the line beyond ridiculous and I feel like some meaning gets lost in the absurdity…and yet. And yet, how can you criticize someone’s narrative trajectory in their comic novel about MS? I feel like the humour and absurdity is a form of resistance, against the cliches and inspiration readers are often seeking in memoirs of disability and illness. The narrative’s all-over-the-placecess too is appropriate for a story of a progressive disease, with the arrival of symptoms where they’re least expected, some improvement, a step forward and two steps back, and then the possibilities that arrive with wild hope, that necessary wild hope—maybe indeed liberation therapy in Costa Rica will produce a miraculous cure? A progressive illness is not a straight line, but neither is any life experience, and so to expect a story to conform to such neatness is an awful lot to ask. I really enjoyed this book, its humour, its wildness, and its point of view—and my appreciation for it was underlined by an understanding of Clark’s background as a playwright. Because while this not the most perfectly shaped novel I have ever read, Clark has got her character’s voice (first person) so exactly perfect. It’s a voice for a monologue, a voice that begs to be performed, funny, generous and wise, and it’s a voice that echoes in the reader’s mind long after the novel is finished.

It’s a quandary, certainly, and not one I’ve ever encountered in fiction before. Melanie Farrell has already done most of the things you read about in novels—she’s come of age, gotten married, been divorced, confronted a life-changing diagnosis (Multiple Sclerosis) etc. etc., but now in Kim Clark’s A One-Handed Novel, her doctor delivers her some devastating news. Her disease is progressing (not news) and a neurological test has revealed she has just six orgasms left. Six! And she’s already spent once since the test, she realizes—what to do? And so begins her journey to use those remaining orgasms to their best and fullest potential, to make each one count. But then best intentions have always been Melanie’s downfall—witness the items on her Twelve Days of Christmas list, which are most consistently “liquor” and “guilt”. With hilarity and so much heart, Clark takes her reader on Melanie’s journey to make the most of her remaining orgasms. A comic novel about MS—who would have thought it? But it’s also about sex, about coming to terms with one’s bodily limitations, and about friendship, money, hope, and community. It’s not so narratively taut—a third of the way through the remaining orgasms conceit is put aside while Melanie travels to Costa Rica for the expensive and controversial “liberation therapy” which fails to deliver the results she is looking for. Clark also relies too much on humour to carry the story, poignant moments rushed by to arrive at a wisecrack. The end of the novel also crosses the line beyond ridiculous and I feel like some meaning gets lost in the absurdity…and yet. And yet, how can you criticize someone’s narrative trajectory in their comic novel about MS? I feel like the humour and absurdity is a form of resistance, against the cliches and inspiration readers are often seeking in memoirs of disability and illness. The narrative’s all-over-the-placecess too is appropriate for a story of a progressive disease, with the arrival of symptoms where they’re least expected, some improvement, a step forward and two steps back, and then the possibilities that arrive with wild hope, that necessary wild hope—maybe indeed liberation therapy in Costa Rica will produce a miraculous cure? A progressive illness is not a straight line, but neither is any life experience, and so to expect a story to conform to such neatness is an awful lot to ask. I really enjoyed this book, its humour, its wildness, and its point of view—and my appreciation for it was underlined by an understanding of Clark’s background as a playwright. Because while this not the most perfectly shaped novel I have ever read, Clark has got her character’s voice (first person) so exactly perfect. It’s a voice for a monologue, a voice that begs to be performed, funny, generous and wise, and it’s a voice that echoes in the reader’s mind long after the novel is finished.

March 22, 2018

“But you see, Meg, just because we don’t understand doesn’t mean the explanation doesn’t exist.”

I wrote about abortion again. Boring, I know, but every time I write about abortion, it seems to more and more politically imperative to do so. And this piece is one of the best essays I’ve ever written, I think. I’m really proud of it and feel good having those words, this story, out in the world. It’s such a common story, but for so many reasons, it’s not one we read about or hear about very often. Though I’m writing it not just for myself and so many women like me whose uncomplicated, ordinary, straightforward stories of abortion are that it was a good thing, a blessing, and simultaneously not a big deal but also such an important part of our lives. I’m writing it also with the hope of reaching someone who sees abortion as killing a baby, and cannot fathom how it could ever be ordinary, let alone a blessing. Not even to change their mind, but to have them entertain the notion of considering a different point of view. “I understand where you’re coming from,” I want to tell them, because I do, “but for a moment just consider my story.”

Which makes me think of a idea that keeps recurring in Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, which I’m reading aloud to my family at the moment. Uttered first in a line by Meg Murry’s mother, who tells her, “But you see, Meg, just because we don’t understand doesn’t mean the explanation doesn’t exist.” Just because someone doesn’t understand my story doesn’t mean my story isn’t true. My story is, no matter how much that complicates your worldview. I’ve written before about being grateful for my abortion, for what it’s taught me about in-betweenness and grey areas, and about the value of listening to people and believing them when they tell you about their experiences. Even if you can’t identify, even if you can’t understand. Because it’s possible that the limits of your understanding are also the limits of your point of view, and I want my ideas to be able to travel further than that. And I hope that other people might see the benefits of such open-mindedness as well.

March 20, 2018

New books by Elisabeth de Mariaffi and Nathan Ripley

Hysteria, by Elisabeth de Mariaffi

The week I was reading Hysteria, I was a bit all over the place, and in the beginning was having some trouble following the novel. “Is it you or me?” I wondered, which was kind of fitting, because the protagonist is wondering the same thing about everybody around her. The novel wasn’t what I’d been expecting either—from the jacket copy, I’d been picturing Gone Girl, domestic suspense, and girls on trains. But then I began reading and found myself in the land of Betty Draper—although not before a prologue with fairy tale elements, a girl lost in the woods and even in the land of Grimms, not far from Dresden near the end of World War Two. But de Mariaffi’s Betty and the girl in the woods turn out to be the same person, just a decade apart. Heike, rescued from a Swiss convent by her American doctor husband—she’d been for a time his patient—who has delivered her to America, and now to a lake house in New York State near the mental hospital where he is working and where Heike will spend the summer caring for their four-year-old son. All of which isn’t to say that I wasn’t enjoying the book—I adored de Mariaffi’s previous novel, The Devil You Know—but instead that I found it disorienting, and I soon realized that I was supposed to. Because Heike, like I felt as a reader, is also out of place and unable to trust her own senses—she’s fragile from her wartime trauma and her husband keeps giving her pills that make her dozy. So that when she starts seeing ghostly images of a young girl, it generally seems in keeping with the spirit of things. And then her son disappears, and Heike’s husband won’t tell her where he’s gone, and it’s around this point when Heike’s agency becomes apparent and she takes up with a television writer inspired by the creator of The Twilight Zone, and I was thinking about The Turn of the Screw and the mechanics of ghost stories. Hysteria was excellent, even before I found my feet, and now I want to go back and find my way through it again.

*

Find You in the Dark, by Nathan Ripley

Find You in the Dark, by Nathan Ripley

Once you’re reading enough books about murder, your standards for gruesomeness start to change, so that all of the sudden you’re on the radio saying, “Oh, yeah, it’s a book about a man obsessed with serial killers and digging up the long-lost remains of their unclaimed victims.” Like that isn’t weird at all, right? Which is the point of Find You in the Dark, by Ripley (a pseudonym for the award-winning Naben Ruthnum), the way that it’s easy to be swayed by the protagonist, Martin Reese, a retired tech millionaire whose hobby just happens to be unearthing remains. Plus, he’s married to the sister of a woman who disappeared twenty years ago, and begins to slip comments about nasty deeds committed in his youth. Is Martin—loving husband and father, albeit a bit weird—really such an ordinary guy? The reader begins to discern that his intentions aren’t as honourable as he’d have us suppose. And we aren’t the only ones who are suspicious, because someone else has found out what he’s up to and there’s a fresh body buried in a decades-old grave, and Martin Reese’s carefully constructed reality is seriously under threat. There’s also a kick-ass police detective who is smarter than he is, so Martin has to figure out something fast. But do we want him to? Is he a good guy or bad? That moral ambiguity is one of the most compelling parts of the novel, whose creepiest aspect turns out not to be the unearthed bodies, but instead the experience of being made to feel so sympathetic to such a messed up mind.

March 19, 2018

The next star.

“If our ability to see detail in a woman’s face is magnified by our visual habits, our ability to see complexity in a woman’s story is diminished by our reading habits. Centuries of experience in looking at the one through a magnifying glass has engendered a complementary practice of looking at the other through the wrong end of a telescope. Faced with a woman’s story, we’re overtaken with the swift taxonomic impulse an amateur astronomer feels on spotting Sirius—there it is! he says, and looks to the next star. It’s a pleasant activity because it organizes and confirms, but it produces the fantasy that a lazy reading—not even a reading but a looking—is adequate, sufficient, complete, correct.”

How incredible when an essay can articulate so much you’ve always understood, and yet at the same time teach you a boatload. I loved this; read “The Male Glance,” by Lili Loofbourow.

March 16, 2018

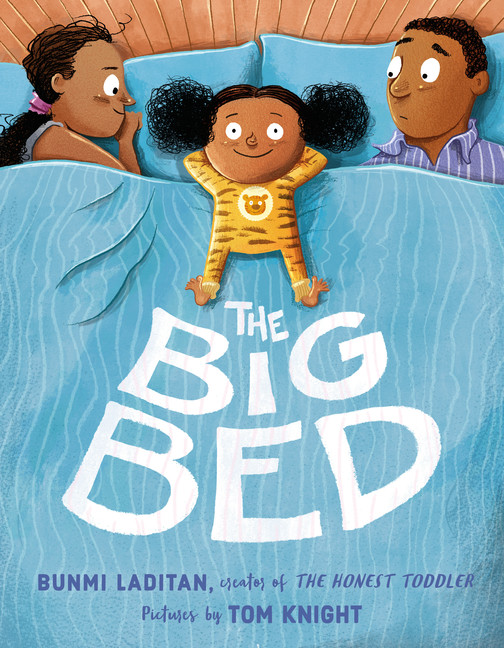

March Break Special: The Big Bed, by Bunmi Laditan

A weird thing is March Break just a week after a week-long vacation, which makes it seem like those few days of school were a blip and we’ve been on vacation forever. And I am the luckiest because I work from home and therefore March Break gets to be a real thing here (except I am also the unluckiest, because it means I have to cram my workday into a couple of hours every morning while my children watch television; come next week I’ll have catching up to do). We didn’t have elaborate plans for the week, but they’ve come together nicely, and we’ve been up to fun things and enjoying evenings without the rush of getting to various activities and also no making lunches. And so to celebrate this free-and-easy week of goodness, I’m making this week’s Picture Book Friday selection a book that my children absolutely adore, a real crowd-pleaser, a book my littlest calls “the pee-pee book,” which is The Big Bed, by Bunmi Laditan, illustrated by Tom Knight.

You probably already know Laditan as the writer behind the very funny Honest Toddler blog and book, and she brings the same approach and humour to her first picture book. It’s written in the voice of a young child who is very persuasive and attempting to explain to her father just why she deserves his spot in the big bed with Mommy. “When day turns to night, it’s normal for people to seek comfort. No one can deny that Mommy is full of cozies and smells like fresh bread. Who wouldn’t want to cuddle with her?” Making good points too: “Quick question: Am I mistaken, or don’t you already have a mommy? Perhaps Grandma is available to sing you to sleep three or four nights a week.” And yes, maybe the narrator does tend to leave the bed a little, um, damp in the morning—but she’s got good three reasons why this is actually a positive thing (even if they are a little yuck). She’s even got a plan, in the form of a camping cot. She’s even going to let her daddy pick out some special new sheets for his “awesome sleeping rectangle.”

It’s a story that resonates for all of us, mostly because there was an extra body or two in our bed for years and I do indeed remember the struggles. Though to those of you still in the midst of sleep struggles or bed woes, maybe hold off on this book for just a little while longer. You wouldn’t want your little bed sharer getting any more ideas….

March 14, 2018

Happy Birthday, Mitzi Bytes!

On the occasion of Mitzi Bytes‘ first birthday, and it being Pi Day (which is A VERY IMPORTANT HOLIDAY) I did the only possible thing and baked a chocolate cream pie whose recipe comes from literary comic icon Nora Ephron. The pie was delicious, and there’s even leftovers in the fridge, which is a fantastic way to be. We didn’t light any candles, but it’s still been a very good way to make a special occasion, a year since this novel came into the world. I’m so grateful for all the places it has taken me to, all the conversations its led me to have, and for all the readers who really engaged with the novel and its questions, and who saw the humour too. It’s all been a dream come true.

March 14, 2018

CBC Ontario Morning Book Picks

I have been reading so much lately, it’s totally ridiculous, but it means I had a whole lot to talk about on my CBC Ontario Morning books column today. You can listen again on the podcast; I come in at 38.20. Sadly. I ran out of time to talk about Hysteria, by Elisabeth de Mariaffi, which I read on the weekend, but I would have told you that it’s kind of a thriller but so much more than that, a little bit Betty Draper and Mad Men too, about a 1950s’ housewife whose perceptions are called into question (by the reader and everyone) when she starts seeing a ghostly girl and then her young son disappears. Is she really hysterical, as her husband is claiming, or is something much more sinister afoot?

March 13, 2018

More Fun at English Bookshops

That we only visited three bookshops seems a bit paltry, although a little less so when you consider we were only in England for six days. My only regret is that this time we didn’t get to visit a bookshop on a boat where we were fed Victoria Sponge Cake, but perhaps that can only happen so often in a lifetime. Our trip to England was a little more local this time, focussed on Lancaster where we’d rented a house for a week. A house that came with a wall full of books, which seemed like a good omen—”But don’t let this make you think we don’t have to go to all the bookshops,” I reminded everybody.

We’d actually visited our first bookshop before we even got to England, because I like the idea of travelling to England with no books, instead picking them up on my travels. Which is pretty risky, actually, considering the decimation of book selection at the Pearson International Airport where there are no longer actual bookshops, and instead a small display of books on display alongside bottles of Tylenol and electrical volt adapters. But I found a couple of titles that interested me, ultimately deciding on Anatomy of a Scandal, by Sarah Vaughan, the story of a political wife whose life comes apart when her husband is accused of rape. A timely book, and it was interesting, but spoiled for me by a “twist” that made this very fathomable story a little bit less so. Which meant that I was all too ready to buy another book at our first English bookshop, Waterstones in Lancaster.

We’d actually visited our first bookshop before we even got to England, because I like the idea of travelling to England with no books, instead picking them up on my travels. Which is pretty risky, actually, considering the decimation of book selection at the Pearson International Airport where there are no longer actual bookshops, and instead a small display of books on display alongside bottles of Tylenol and electrical volt adapters. But I found a couple of titles that interested me, ultimately deciding on Anatomy of a Scandal, by Sarah Vaughan, the story of a political wife whose life comes apart when her husband is accused of rape. A timely book, and it was interesting, but spoiled for me by a “twist” that made this very fathomable story a little bit less so. Which meant that I was all too ready to buy another book at our first English bookshop, Waterstones in Lancaster.

I love the Waterstones in Lancaster. My heart belongs to indie bookshops, but Waterstones is better than your average bookshop chain, and the Lancaster Waterstones in particular, which its gorgeous storefront that stretches along a city block. With big windows, great displays, little nooks and crannies and staircases leading to more places to explore. It’s a gorgeous store, with great kids’ displays too, and my children were immediately occupied by reading and also by a variety of small plush octopuses. I ended up getting Susan Hill’s Jacob’s Room is Full of Books, a follow-up to Howards End is on the Landing, which I bought when we were in England in 2009 and Harriet was a baby and I spent our week there reading it while she napped on my chest. Jacob’s Room… would turn out not to be as good as Howards End…, which broadened my literary world so much (and introduced me to Barbara Pym!). The new bookwas kind of rambling and disconnected and not enough about books, but was so inherently English that I was happy with it.

On the Wednesday we drove across the Pennines to Ilkley to visit The Grove Bookshop, which is one of my favourite bookshops ever. It’s located up the street from Betty’s Tea Room, which makes for one of the best neighbourhoods I’ve ever hung out in. After afternoon tea, where the children behaved impeccably, we took them to a toyshop for a small present as reward, which was good incentive for their behaviour in The Grove Bookshop too, where I was able to browse for as long as I liked. I love it there, the perfect bookshops and well worth a trip halfway across the world. I had been in the mood for a Muriel Spark novel since reading this wonderful article, and The Grove Bookshop delivered with The Ballad of Peckham Rye, a new edition in honour of Spark’s centenary. I was also very happy to find a rare copy of Adrian Mole: The Collected Poems, as Mole’s work has had a huge impact in my own development as an author and intellectual.

I really loved The Ballad of Peckham Rye, so weird and contemporary in its tone, strange and meta, the way all Spark’s work is. When we’re on vacation, I don’t like getting out of bed, lingering instead with a cup of tea and toast crumbs, and Peckham Rye was perfect for that,

On Friday we went to Storytellers Inc, located in Lytham-St. Anne’s, just south of Blackpool. Originally a children’s bookshop, they’ve branched out to books for readers of all ages, although the children’s focus remains—they have a huge selection of kids’ books and a special kids-only reading room with a tiny door and kid-sized furniture. (Sadly, we’d not brought our kids along with us that afternoon and it would have been weird to go in there without them.) In addition to the kids’ books, they had lots of Canadian fiction, and poetry. We ended up buying Welcome to Lagos, by Chibundu Onuzo, just because we liked the cover. And also Motherhood, by Helen Simpson, because I’d seen it on the shop Instagram page, and then I saw that Emily was reading it.

I don’t think I’ve ever read Simpson before, but this is a mini-collection of her stories from a few different books over the decades—and I loved it. Plus there was a boob on the cover. I finished reading it on the plane journey home, and then started Welcome to Lagos, which was really great. It’s Onuzo’s second novel, after the award-winning The Spider King’s Daughter. The latest is about a ragtag crew who arrives in Lagos and attempts to make a life there, in spite of the odds. They end up running in with a corrupt former Minister of Education with a suitcase full of money, and what they choose to do with this fate will make or break their destinies. In this case, choosing to buy a book for it’s cover was a very good decision.

March 12, 2018

Yoko Ono, “The Riverbed,” at the Gardiner

I loved Yoko Ono’s “The Riverbed”, which we went to see yesterday at The Gardiner Museum. An exhibit whose first part is “Stone Piece,” an arrangement of river-worn stones which we are invited to pick up, and contemplate, and (for some of them) to discover words written on their bottoms, and then replace the stones in a different arrangement, the exhibit ephemeral and ever-changing, always moving, like a river itself. Cushions around the display invite viewers to sit down and watch the scene, the way we might want to sit by the side of the river, and the effect is similar—relaxing, interesting, and insightful. It’s a scene where adults and children alike are excited to be taking part in the exhibit, to be a part of things, and watching this is interesting as well.

Next we move on to “Mend Piece”, where broken crockery has been placed on the table and we are invited to put the pieces together using tape, and string, and glue. A fascinating process for so many reasons—because the pieces we’re “mending” weren’t necessarily put together in the first place, the idea that to mend is a creative act, to make something too, how mending is restorative and generative at once. About how out of broken things there can be made something new, and strangers sitting together at the table connect as they share materials, and also as they’re served coffee from the coffee stand that is part of the exhibit. When the “mending” is done, the new object is placed on a shelf or hung on the wall, and thereby viewers now have a piece on display at the Gardiner, which is kind of incredible.

Everything is white, and there is so much light, which, when coupled with the creative acts taking place, allows for lots of thinking—but the soundtrack is the racket of nails being driven into a wall. Which was meaningful to me, being required to think over the noise, which is important. The noise too a reminder of work, the necessary parts of building anything. And the work that’s being done is in “Line Piece,” where viewers can hammer a nail into the wall and tie a string from one point on the wall to another. Which has created the most fascinating space, cushions on the floor again where you can look up and think about the web of string above, the web that would have been different if you’d never come, the web that will be something else different tomorrow. And to stand up too, pop my head up through the web and contemplate the networks of string from above… It’s about connection, and shelter, creativity and possibility.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the exhibit. Conceptual art can go all kinds of ways, and making the viewer a participant in the process doesn’t always succeed in being meaningful. But I still remember the story of John Lennon falling for Ono back in the 1960s’ when he went to her exhibit and climbed to the top of a white ladder to see a word through a magnifying glass, and the word he saw was YES. After our experience yesterday at “The Riverbed,” now I see how that could happen.