September 25, 2018

Moon of the Crusted Snow, by Waubgeshig Rice

“‘Yes, apocalypse! What a silly word. I can tell you there’s no word like that in Ojibwe. Well, I never heard a word like that from my elders anyway.”

“‘Yes, apocalypse! What a silly word. I can tell you there’s no word like that in Ojibwe. Well, I never heard a word like that from my elders anyway.”

The first sign that something is wrong is the home satellites stop working, TV screens gone dead. “We might actually have to have a conversation,” Nicole tells her partner Evan when he comes from hunting a moose, and they will pass the evening without their usual entertainment. And by the morning, they’ve lost cell phone service, cell towers a pretty recent arrival in their remote northern community anyway—only built because contractors for the south wanted a signal while they built the hydro dam, and the tower stayed even after they were gone. But there’s no signal now, and soon the landlines will stop working, and the power grid will cease to function. Which raises two big questions: What has happened to the rest of the world? And the more immediately pressing one: how will their community get through the winter?

On the latter point, Evan has some advantages—he can hunt and has been storing food; he’s been reconnecting with the traditions of his Ancestors and this wisdom will guide him; and he and Nicole have built a stable life for their family, which will provide the emotional sustenance necessary to survive a dark and barren winter. But they are challenged when Southerners begin to arrive in the community, fleeing the devastation of towns and cities in the south—one of these men in particular is dangerous. And other members of the community prove to be susceptible to this man’s influence, which begins to divide them at a time when cooperation is essential.

Moon of the Crusted Snow is Waubgeshig Rice’s third book, and it’s gorgeously designed, the story itself quiet and subtle, but fast-paced with heavy overtones. Evan’s reconnection with Anishinaabe traditions as his community is becoming disconnected from the world around them sets up an interesting disjunction, and Rice shows the ways that he has consciously woven these traditions into the life of the family he’s created with Nicole, and how these connections serve them when the situation becomes particularly dire. Evan is also learning the Ojibwe language of his people, and this language is included seamlessly in the text without the use of italics or translation, which offers the text an additional layer of meaning to those who can read Ojibwe—does “zhaagnaash” really mean “helpful friend” I wonder, when used toward Scott, the man who has arrived in their community with big guns and survivalist tendencies?

And yes, there is no Ojibwe word for “apocalypse,” which Evan learns through a conversation with Aileen, an Elder whose teachings he carries with him. Aileen explains to Evan that their world isn’t ending—it already ended long ago when settlers arrived. “When the Zhaagnaash cut down all the trees and fished all the fish and forced us out of there, that’s when our world ended.” But they survived—this is her point. They learned to adapt, and to survive, even as their children were taken and abused in residential schools for generations. “But we always survived,” she tells Evan. “We’re still here. And we’ll still be here, even if the power and the radios don’t come back on, and we never see any white people ever again.”

The ending of this novel is powerful, unexpected, and while deeply satisfying, it’s also ambiguous in a really fascinating way. Moon of the Crusted Snow is a terrific, gripping novel, and one of the highlights of my literary autumn.

September 21, 2018

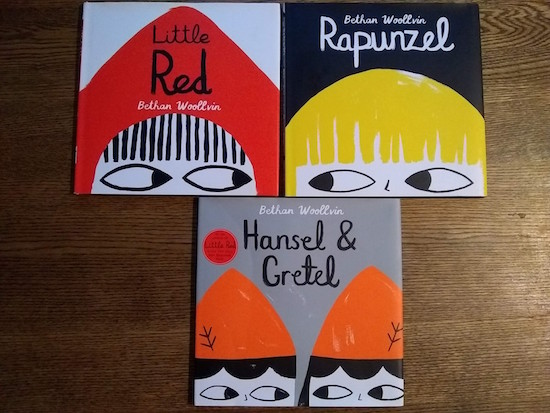

Hansel & Gretel, by Bethan Woollen

Things get a bit weird in Bethan Woollen’s Hansel & Gretel, which is a book you’ve probably got to get if you’ve read her Little Red and Repunzel and you have completist tendencies. See photo below for what I’m talking about:

Once again, Woollvin is revising a fairy tale we think we know, but this time she’s telling it from a different point of view. Yes, a house made out of gingerbread might turn out to be all too tempting for a brother and sister who are lost in the woods, but luring children wasn’t what the good witch Willow had in mind when she conjured the spell to build her house. A miscalculation, maybe, but when Hansel and Gretel come tramping through the woods scattering breadcrumbs, which are sure to lure mice and other pests and therefore put Willows gingerbread house at risk, she politely asks them to clean up the crumbs, which they refuse. And when she has her back turned cleaning up the crumbs herself, the recalcitrant pair begin snacking on the house, which might be the final straw for some witches, but not this witch, who determines Hansel and Gretel must be hungry and invites them to come in for dinner.

It turns out that Hanesel and Gretel have no manners at all, however, and they gobble up all of Willow’s food, then start messing with her spells and wands, turn the black cat gigantic, and then Gretel stuffs Willow into the oven so she and her brother can continue to make trouble—but then the house is so full over magic, it explodes: “It was only made out of gingerbread after all.”

And so it is here that Willow finally decides to get her comeuppance, concocting a nasty bit of revenge that Hansel and Gretel completely had coming, and which hearkens back to a bit of fairy tale darkness worthy of Grimm’s.

September 19, 2018

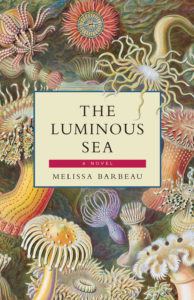

The Luminous Sea, by Melissa Barbeau

If, like me, you are drawn to Melissa Barbeau’s debut, The Luminous Sea, because of its cover (Ernst Haeckel!) then keep on going because the novel itself is just as gorgeous and rich with wonder. Beginning with Vivienne, a university researcher charged with collecting data on the phosphorescent waters off the coast of Newfoundland, not anticipating her next catch—a sea creature unlike anything anyone’s ever seen before. A little Shape of Water, but there’s no sex in the bathtub, and Vivienne and her supervisor, Colleen, create a tank out of a chest freezer instead. And the creature is a female, or at least Vivienne keeps calling it “she,” even as she’s admonished for the anthropomorphizing. Dynamics in the lab are getting complicated—Colleen’s superior arrives and attempts to take control of the discovery, and in a shocking act of violence (exquisitely rendered in prose like you’ve never seen before) he tries to subdue Vivienne as well. Meanwhile, Colleen is carrying on an affair with a local cafe owner whose wife is wise to it all and spends her time making preserves out of such unlikely things as jellyfish, and Vivienne is only there at all because she’s run away from a broken relationship with her girlfriend in the city. And in the meantime, the creature is not doing well in the tank (“Three days in and scales were coming off in her hand when she touched her, like flakes of opalescent pearls…”), and it might be up to Vivienne to save it. So that this extraordinary novel whose sentences and imagery shimmers and shines is also taut with tension, fast-paced, impossible to put down. But oh, the writing! It’s the writing I keep going on about. The following is my favourite part:

If, like me, you are drawn to Melissa Barbeau’s debut, The Luminous Sea, because of its cover (Ernst Haeckel!) then keep on going because the novel itself is just as gorgeous and rich with wonder. Beginning with Vivienne, a university researcher charged with collecting data on the phosphorescent waters off the coast of Newfoundland, not anticipating her next catch—a sea creature unlike anything anyone’s ever seen before. A little Shape of Water, but there’s no sex in the bathtub, and Vivienne and her supervisor, Colleen, create a tank out of a chest freezer instead. And the creature is a female, or at least Vivienne keeps calling it “she,” even as she’s admonished for the anthropomorphizing. Dynamics in the lab are getting complicated—Colleen’s superior arrives and attempts to take control of the discovery, and in a shocking act of violence (exquisitely rendered in prose like you’ve never seen before) he tries to subdue Vivienne as well. Meanwhile, Colleen is carrying on an affair with a local cafe owner whose wife is wise to it all and spends her time making preserves out of such unlikely things as jellyfish, and Vivienne is only there at all because she’s run away from a broken relationship with her girlfriend in the city. And in the meantime, the creature is not doing well in the tank (“Three days in and scales were coming off in her hand when she touched her, like flakes of opalescent pearls…”), and it might be up to Vivienne to save it. So that this extraordinary novel whose sentences and imagery shimmers and shines is also taut with tension, fast-paced, impossible to put down. But oh, the writing! It’s the writing I keep going on about. The following is my favourite part:

“A long stainless steel table is in the middle of the room. Next to it a second table made from a wooden door laid across two wooden sawhorses and covered with sheets of plastic. Instruments and vials, pincers and thermometers and gloves, measuring tapes and suction-cupped monitors are arranged in near rows on top of it. The doorknob is still attached to the door and makes a small mound underneath the plastic. Vivienne wonders if they have not made some kind of underestimation when considering door security. It seems as if at any minute someone might turn the handle on the supine door, throwing scientific instruments across the room; that someone will will up through the horizontal doorway, like that party trick where someone climbs an imaginary set of steps in the carpet behind the couch.”

Do Not Underestimate Door Security turns out indeed to be one of the novel’s many morals, and maybe (definitely) I’ve got a thing for door imagery anyway, but that paragraph for me is emblematic at how beautifully imagined this novel is, its realities and its many possibilities. There is a generous expansiveness at the heart of the book, doorways onto doorways, but it never grows too strange and mystical and stays controlled, anchored in the physical world, with such attention to accuracy and detail, scientific, like the image on the cover. Melissa Barbeau is an extraordinary writer, and I can’t stop talking about this book.

September 18, 2018

Transcription, by Kate Atkinson

This post is less a book review than “How I Spent My Weekend.” I don’t really know that I’m capable of reading a Kate Atkinson novel critically, or if I’d even want to be. I read them for pure enjoyment, delight, for her narrative tricks, and the way she plays with history, and story. For the little twists that make her books so unforgettable, and how they get lodged in the mind, like how I’m still even thinking of Behind the Scenes at the Museum, even though I read it thirteen years ago.

Since then, Atkinson has waded into detective fiction (igniting my own love affair with the genre) with her Jackson Brodie novels, and then in her two most recent books exploring historical fiction, as ever probing at the limits of what a novel can hold, just how far it can stretch. And that her latest is a spy novel set during during WW2 and also in 1950 is not at all incongruous. Questions of duplicity, reliability, truth and lies, and how History agrees with the factual record are what has fascinated Atkinson from the start of her writing career. I’ve always said that all her books have been mysteries (and maybe all books are in general) and maybe they’ve always been spy novels too.

Transcription is about Juliet Armstrong, something of a cypher, who gets a job with MI5 in 1940 transcribing meetings between a government agent and people who believe they’re reporting state secrets to the Gestapo. As with any book about English fascism during the 1930s/40s (including Jo Walton’s Small Change series) there is a contemporary resonance, although it’s subtle here. In addition to her transcribing, Juliet is enlisted to infiltrate The Right Club, a group of German-sympathizers, taking on an additional identity. And all of these war-time activities come back to haunt her a decade later as she’s working at the BBC (Atkinson has said this part of the story was inspired by Penelope Fitzgerald’s Human Voices) and finds old associates in close proximity again. What do they want from her? What does she have to offer them? Is this just paranoia on her part—there are references to the movie “Gaslight.” How much can the reader trust Juliet at all?

I loved this book—but of course I did. I read it in two days and delighted in that very rare and always exquisite, “I’m reading a Kate Atkinson novel for the first time” feeling. And like all her books, it will bear rereading, even once the twist is known. Because Kate Atkinson is always about more than just tricks, but instead about textual richness, and all the clues you missed that were glaring all along.

September 17, 2018

Motherhood and the Map

In July, Lauren Elkin wrote an essay about a new and sudden influx on books about motherhood, and I rolled my eyes at the idea. Because of course Lauren Elkin is pregnant with her first child, which is around the time that most literary people discover the existence of a motherhood canon. “Motherhood is the new friendship, you might say. These are books that are putting motherhood on the map, literarily speaking, arguing forcefully, through their very existence, that it is a state worth reading about for anyone, parent or not.” Which annoyed me not just because after nearly a decade of motherhood, because of course it’s been on the map all along—and I even did my part to expand its boundaries by editing The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood in 2014. But also because Elkin’s discovery of motherhood reminds me of my own earnest revelations of a decade ago, that parenting indeed is not “a niche concern,” and it’s a little embarrassing to see one’s naivety reflected in such stark terms.

In July, Lauren Elkin wrote an essay about a new and sudden influx on books about motherhood, and I rolled my eyes at the idea. Because of course Lauren Elkin is pregnant with her first child, which is around the time that most literary people discover the existence of a motherhood canon. “Motherhood is the new friendship, you might say. These are books that are putting motherhood on the map, literarily speaking, arguing forcefully, through their very existence, that it is a state worth reading about for anyone, parent or not.” Which annoyed me not just because after nearly a decade of motherhood, because of course it’s been on the map all along—and I even did my part to expand its boundaries by editing The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood in 2014. But also because Elkin’s discovery of motherhood reminds me of my own earnest revelations of a decade ago, that parenting indeed is not “a niche concern,” and it’s a little embarrassing to see one’s naivety reflected in such stark terms.

The other week, two of my library holds came in at once: Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, by Kate Manne, and And Now We Have Everything: On Motherhood Before I was Ready, by Meaghan O’Connell. I read Down Girl at once, and found it illuminating and really profound. I’ve since had to return the book—there are many holds on it after mine—but if I still had a copy here I’d been sharing the lines where she writes the misogyny inherent in our understanding that the history of feminism occurs in waves, each one sweeping away whatever came before. Instead of us there being a more constructive model of this history, something indeed that is cumulative. I was struck by this idea, by the way that waves must undermine us. As Michele Landsberg explains in Writing the Revolution: “Because our history is constantly overwritten and blanked out…., we are always reinventing the wheel when we fight for equality.”

I didn’t pick up Meaghan O’Connell’s memoir at all, however, until I received a note from the library that it was two days due. I’d been resisting the book for ages, since seeing it in the bookstore and deciding I didn’t want to pay the price of a hardcover for a book that was slight, so I was content to be the hundredth-something library hold, and even once I brought the book home, as I’ve said, I still didn’t read it. Partly for the same reason I found Lauren Elkin’s essay annoying. “We have lacked a canon of motherhood, and now, it seems, one is beginning to take shape.” OH GOD, NO. (Note: Please read my review of Val Teal’s amazing and irreverent 1948 mothering memoir, It Was Not What I Expected: “It is often said that nobody tells the truth about motherhood, though I think the reality is really that nobody ever listens.”) I’d read enough motherhood memoirs for one lifetime, I decided. There was indeed nothing new under the sun, even if you happen to be raising your baby in Brooklyn.

But then it wasn’t a very long book—the very reason I hadn’t bought it. Perhaps I could even get it read in two days (because such expansiveness is possible in the life of a mother whose children are nine and five). There were many holds on this book as well and it could not be renewed, so I picked it up and started reading, and what happened next, like motherhood, was not at all what I’d expected.

Reader: I really, really liked it, this story of a woman who got pregnant when she was 29 and decided to have a baby before she even owned a home or a car. Unlike O’Connell, my baby was planned when I got pregnant when I was 29, but we were similarly missing the house and car and career stability (actually we’d just decided to skip those) and there were people who, when they heard I was pregnant, had asked me, “Oh, Was it planned?” I identified so much with O’Connell’s story of motherhood before she was ready, and it brought back so many memories I’d forgotten about altogether—like when she jumps up from the table at last once a week to run to the bathroom because she’s convinced she’s started to miscarry and then comes back sheepishly, “False alarm.” How the pregnancy never feels real, except for about forty minutes after she’s had a sonogram. About reading Ina May Gaskin and deciding that you too can be a hero. And once her baby is born—that failure of imagination. The double standard of a society that demands you breastfeed but doesn’t know where to look when you do it. O’Connell writes that she’d known it would be hell, but had imagined the hell would be logistical instead of emotional. And that was the part where I put my finger on the line of text and shouted, “Yes, this exactly.”

I’d forgotten so much of it—and I have probably read and written about motherhood more than the average person. But so much of the story had disappeared from my consciousness, swept away—like as a wave, as it will. And I’d even decided that stories of new motherhood were no longer relevant to me, that I was done with al that. The same problem as Lauren Elkin but in reverse. Scoffing, of course, there’s always been a motherhood canon, but now it’s dusty on the shelf and I don’t even need to read it.

There might be something to the waves, something more than misogyny. I wonder if men’s lives are more linear than women’s, whereas I know that in my own experience, with motherhood in particular, my self has been continually overwritten. As it has been again now that my children are more independent, and as it will be when they get even older, and then with menopause—all these changes. I don’t remember who I was before. I don’t remember when I ever needed those books. Sometimes I pick them up and read my notes in the margins though, and it’s like they were written by a stranger.

September 14, 2018

In the woods, on the radio, and online!

We had an amazing time at the Dunedin Literary Festival “Words in the Woods!” last weekend, where I had the privilege of moderating a panel with Karma Brown, Tish Cohen, and Uzma Jalalludin. It was a very good day and left me excited for my next event, which takes place on September 23 in Huntsville as part of Huntsville Public Library’s Books and Brunch series. I’ll be there with Hannah Mary McKinnon and K.A. Tucker, and all of us appeared on the most recent episode of the library’s very own radio show (how cool!) Keeping Up the Librarians—you can listen to it here. And I was also happy to take part in the “Behind the Scenes With Book Reviewers” series at the Hamilton Review of Books, which was published this week—go here to learn all my book reviewing secrets.

September 14, 2018

Pinny in Fall, by Joanne Schwartz and Isabelle Malenfant

Before Joanne Schwartz was taking over the literary world with her beautiful picture book, illustrated by Sydney Smith, Town Is By The Sea, she was author of a whole bunch of other lovely picture books, among them the perfectly delightful Pinny in Summer, which we fell in love with two years ago and inspired us to bake a cake. And so we’ve been looking forward to Pinny’s return with Pinny in Fall, a collection of four miniature adventures that demonstrate the amazing possibilities of a single day, smallness (and slowness) writ large in an approach that reminds me of the Frog and Toad books.

“Does Pinny have parents?” my children wonder when we read this book, and I tell them that her parents are probably curled up in comfortable chairs somewhere reading. Which means that Pinny can do whatever she wants to—in the first story she wakes up and does her stretches, and then packs a small bag for her morning walk, with a sweater, a rain hat, a snack, and her book. Plus her treasure pouch, which was hanging on a hook by the door.

On her walk to the lighthouse, she encounters her pals, Annie and Lou, and they play tag in the wind and the fog, and then Pinny shares her snack and they read poetry. “The sun slipped behind the clouds, once, and then it was completely gone.” The fog is getting thicker in the third story (which Malenfant renders beautifully in her art) and Pinny and her friends have to rush to help the lighthouse keeper sound the foghorn and light the light. With their help, a ship safely navigates its way along the rocky shore, and the lighthouse keeper rewards the children: a piece of beach glass for each of them. Pinny slips hers into her treasure pouch.

And in the final story, Pinny is sipping hot chocolate by her window. As with Pinny in Summer, the colours in this book are particularly and beautifully hued, and the light that shines into Pinny’s room at the end of the day continues to be the most wonderful thing. This time coloured by the leaves falling outside her window: “A Special Kind of Rain.” After going outside to soak in it, she comes back in and the day is nearly done—her takes the beach glass from her treasure pouch and sets it on the window. “The glass had been washed so smooth by the ocean, it glowed in the twilight like a tiny bacon of light.”

Pinny in Fall is a gorgeous, old-fashioned story with such reverence for language, and wholly infused with a sense of wonder that will inspire readers to look at the world differently and seek out adventures of their own.

September 13, 2018

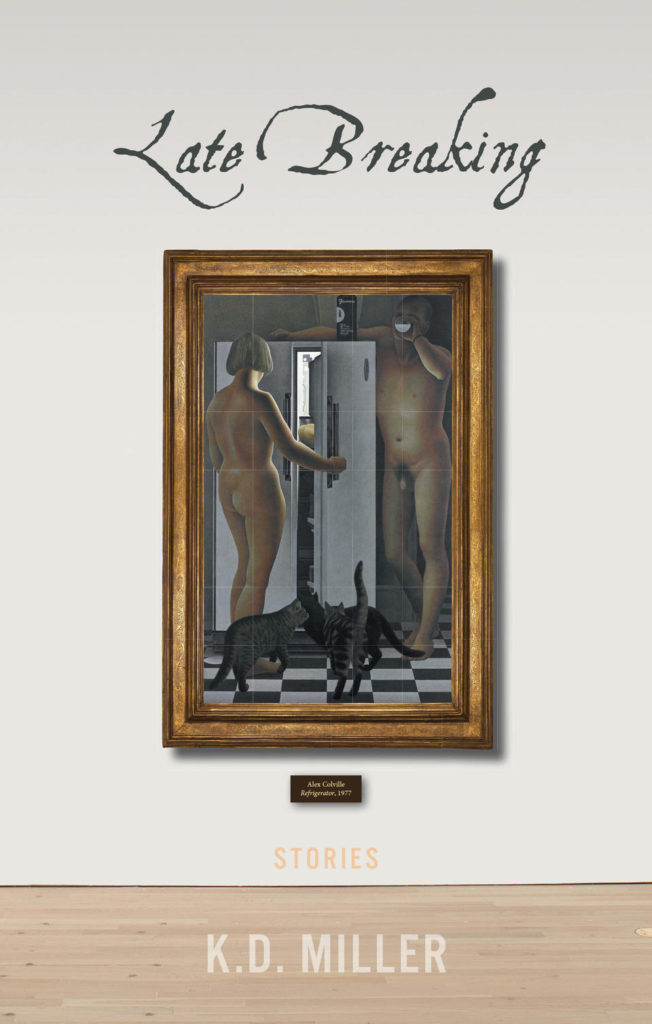

Late Breaking, KD Miller

So, if we’re talking about remarkable things, let’s start with the obvious one: the cover. How many other book covers this season feature a naked man drinking milk? I’ll wait. And in the meantime, we can talk about “Refrigerator,” by Alex Colville, which on the advanced copy of K.D. Miller’s Late Breaking that I read was less subtle than it is on the finished version, above. Which meant I felt kind of conspicuous reading it in the dentist’s waiting room the other day, but then I got over it, because the book is so excellent that the penis on the cover quickly ceases to be the point.

And so too does this collection’s conceit, which is that each story is inspired by an Alex Colville painting. Which is not to say that this way of collecting stories into a book is not compelling—absolutely not. It’s an fascinating idea that adds additional texture to Colville’s work, and the stories themselves are similarly absorbing, both ordinary and extraordinary at once, and disturbed by an uncanny strangeness—like the gun on the table, a horse on the train track. Each story is preceded by an image of the painting that inspired it, and the connections between the works are surprising and illuminating both ways.

But this too is eclipsed by something far more central to the text when we talk about the collection: which is that the stories themselves are incredibly good. The first story (inspired by “Kiss With Honda”) is about a widower whose relationship with wife was tainted by a secret she never knew he realized and was never able to explain before he dies, and then he goes to visit her grave, which leads to an act of violence that comes out of nowhere—and suddenly we realize that these stories have teeth, and claws. The second story is about Jill, an older woman whose novel has been shortlisted for an award, and she’s touring with a motley crew of other nominated authors, all the while reflecting on the sex-lives of septuagenarians and the relationship (and heartache) that inspired her work. The third story, “Witness,” takes Colville’s painting “Woman on Ramp” literally—Harriet is the woman on the ramp, and after coming out of the lake and into her cottage, she finds an arm around her neck and something sharp against her back. “Olly Olly Oxen Free” is about the marriage between a woman and her husband, a failed novelist, intersected with story of an older woman in her book club who still carries the pain of a traumatic childhood event. In “Octopus Heart,” a lonely man (who turns out to be the one who broke Jill’s heart in the second story, five years before) feels the first intimate collection of his life with an octopus from the aquarium. In “Higgs Bosun,” a woman (whose son is married to Harriet’s son from a previous story) thinks about the ways she’s tried and failed to hold the world and her family together. In “Lost Lake,” the family from “Olly Olly…” are away at an isolated resort where their daughter seems to be visited by sinister supernatural forces. “Crooked Little House” takes us back to the widower from the first story, and his neighbour (who is the estranged daughter of the octopus man), and their friendship with another man who is trying to make a clean start after twenty-five years in prison. For the murder of a woman who, we realize in the next story, was a friend of Harriet and Jill, all of them meeting one summer long ago—and this story begins with a wonderful scene in a locker-room, older women squeezing into their bathing suits without regard for their naked bodies. “Have we all just given up? Harriet thinks, hanging her suit on a hook in one of the shower stalls and rinsing down. Or is this wisdom?”

These are all rich and absorbing stories on their own, but even richer for how they also inform each other. Eventually I would be making a chart in the back of the book to figure out all the surprising connections, including the final story, about the murdered girl’s mother who was also author of a book about octopuses that preoccupied a character in a previous story. Similar to my friend Rebecca Rosenblum’s work, K.D. Miller’s fiction seems to conjure whole worlds, with characters who seem to walk off the page and who—one has no doubt—continues in their adventures even when their stories are finished. We get glimpses of these people, but they’re like the tip of an iceberg and there’s so much more going on beneath the surface. Which is something you could say about the people in Colville’s paintings too, and about each of these stories themselves, compelling and disturbing, and impossible to look away from, creating the most terrific momentum.

September 12, 2018

Unabashed

I remember the first time I had courage to stand up and confront an anti-abortion protester. It was the summer of 2015 and I’d just dropped off Harriet at day camp, and the year before I’d published an essay about how becoming a mother taught me everything I knew (and was grateful for) about my abortion. Which meant that I’d thought about abortion a lot, and was comfortable talking about mine in public, and had a lot to say about my experiences, actually. Even though I usually shy away from conflict, and don’t get off on debate just for the fun of it (because, unlike a lot of anti-abortion protesters, it’s my bodily autonomy we’re talking about. These ideas, for me, aren’t abstract, and I will probably cry). These people are able to dominate the abortion conversation like they do because most of us don’t know how to talk about our abortions in public (and why should we have to? We don’t require men to issue public defences of their prostate surgeries). But I’d had enough to having these people be the loudest people when we talk about abortions, of their taking advantage of civility and politeness to scream the loudest. I was ready to talk, and so I did, and it was exhilarating, and terrifying, and very empowering to be able to tell this young man holding a sign: “I KNOW MORE ABOUT THIS THAN YOU DO. YOU’VE GOT A SCRIPT, BUT THIS IS MY LIFE STORY.”

Unfortunately, however, arguing with these zealots gets you nowhere, and while it feels good not to be silent, these conversations are always a waste of energy. So I had this idea that maybe I could make a sign, and luckily I’m married to a standup guy who makes signs for a living (among other talents) and so I said to him, “What if you made me a pro-choice sign I could fold up and carry in my purse? So I could have it on my person at all times in case of an emergency, and be there are represent and have my voice heard, but not have to talk to these abusive nefarious creeps that get off on turning women’s private experiences into public spectacle?” And my husband said okay, and he designed my sign and had it printed, and I’ve been carrying it around for nearly two years now, but there’s that rule about only ever having a thing when you don’t need it. I’ve not seen anti-abortion protestors since the Christmas I found my “My Body My Choice” sign under the tree. Which I wasn’t sorry about—maybe the sign was like some sort of repellant, and in that case, good riddance. I had my sign and women in my neighbourhood were free to walk about the streets without the abuse of gory and misleading photos of fetuses.

But no repellant lasts forever, it seems, because today I got word of the usual suspects setting up shop a few blocks from my house. So I walked over there, where a respectable counter-protest had been set up by Students for Choice and I was honoured to join them with my little sign (and my actual life experience, which is short on the ground on the pro-life side). And there I stood for an hour as people said thank you and others rolled their eyes at the display, and men stood behind me having rhetorical arguments on the matter of my bodily autonomy and didn’t seem anything ironic about that. As I said so beautifully in all-caps on Twitter: “Do you know what’s more arbitrary than Canada’s lack of an abortion law so that abortion is a decision between a woman and her doctor? AN ABORTION LAW DECIDED BY SOME RANDOM GUY ON THE SIDEWALK.”

This morning I read Anne Kingston’s article about plans afoot by the anti-abortion movement to make their cause a political issue everywhere, and it’s terrifying. It’s terrifying, because the most of us are going to continue to be civil and polite and let them continue to dominate the discourse with misrepresentation and lies—all the while our reproductive rights are eroded. But my daughters—who would not exist were it not for abortion and the choices I was free to make—deserve to have the same freedoms that I was lucky enough to be able to take for granted. And it’s not even just about them, or about abortion either—THREAD, as they say: “Reproductive justice is about bodily autonomy, it’s linked to racism and immigration and incarceration, it’s about classism and supremacy, it’s all connected to climate change and accessibility and colonialism…” writes Erynn Brook.

Reproductive justice is linked to everything, and it’s about standing up and speaking out for our rights right now. As unabashed as we want to be. About this, there is no choice—it has never been more important.

September 11, 2018

I am a swimmer

What I have to show for my last decade in athletics is not a whole lot—I once signed up for ten yoga classes but only went to one, and we still have the evidence of the running shoes my husband bought me when I decided to take up jogging that show remarkably little wear. Which is just two examples, and narratively anti-climactic, but it underlines the point I’m trying to make: I dislike most forms of exercise so much that I rarely quit them, because I’d have to join them first. Not doing things I dislike doing is pretty much the cornerstone of my approach to being alive: I don’t want to push through the pain, or feel the burn. If being miserable, even for limited periods of time, is a pre-requisite for physical activity, than take my name off the list. For a while I made do with a stationary bicycle, because while riding it at least I could read.

But now—like the shoes, and like the yoga passes nearly a decade expired, the stationary bicycle sits unused—draped with winter coats in an upstairs closet. It’s been at least two years since I’ve sat upon its little seat and spun its futile wheels into nowhere—but not for the reason you might be thinking. Oh, no. Because it’s also been two years now since I purchased a membership to the university athletic centre near my house. A membership I bought (inspired by Lindsay) just after getting a raise at my job and therefore being able to afford to put my youngest daughter in full-day preschool, which left time in the day for some kind of physical activity. I would go swimming, I decided. Maybe this would be a thing I could do, and I wouldn’t quit, because it wouldn’t be awful.

And it wasn’t, and I didn’t. And in the next few days, I will renew my membership again. Because I love it, swimming. I love it so much, I get up early in the morning to do it, much to the surprise of the people who know me, because it’s the only thing I’ve ever gotten out of bed for, and before 7am either. Four days a week (but not Friday, because on Friday everyone at rec swim is crammed into half of the 50 metre pool—the long half and not the short half—and it’s crowded and unpleasant) I wake up at 6:50 am and wriggle into my bathing suit, which is set out with my towel. Throw on clothes over top and rush to the pool, where I’m in the water by 7:15, and I swim for half an hour. During which I think, catalogue anxieties, solve plot problems, compose blog posts, try to remember all the verses to “American Pie,” and swim back and forth in the medium lane. Which is so my speed—the medium lane. It’s where I like to be.

I’ve loved swimming for a long time—I was lucky to have a pool in my backyard when I was growing up, and so even though I failed Bronze Cross twice because I couldn’t do the timed swim, I recall spending ages under water, turning somersaults, leaping high, partaking in an agility I did not partake in on dry land. When I lived in England, I longed for lakes, and once went swimming in a pond just to get my fix. One day on holiday in 2004, Stuart and I jumped into a hotel pool and discovered after two years together that we both liked swimming a lot, so much so that later in the week we’d jump into another hotel pool even though it was green, and I’d get a rash—me getting a rash will become a running theme here. And when I was pregnant with Harriet, I worked at the university, and went swimming every day on my lunch hour, delighting in the freedom of movement, and of floating suspended the way my baby was—the very first thing we ever did together.

But it’s hard to fit swimming into a busy life. For a long time, swimming was a special occasion, and I started buying expensive mail-order movie star bathing costumes to better suit my weird-postpartum body. But the thing that no one tells you about movie star bathing suits is that when you wear them a lot in chlorine, they become worn out and hideous. Six years later, my body even weirder and more-postpartum, I buy unflattering sporty suits from the clearance rack, because I like the uniform, its utilitarian nature. I am not a bathing beauty, I am a swimmer. I am a swimmer. In Swell: A Waterbiograpy, Jenny Landreth writes about the power of this realization, her reluctance to own it, how we undermine our abilities—”I’m not that good. And I’m not fast.” To belong in a space like a pool, a gym. I have a place here. It has been two years, and I am a swimmer.

I am allergic to lake water, and have a sunlight sensitivity that a lot of other people have tried to tell me that they have experienced too, and some of them have, but not the ones who say, “It’s like a heat rash, right?” Because those people have never had their eyelids swell up or been unable to sleep for unbearable itching. This year was the third summer in a row that I’ve gone through in big hats and SPF clothing, including a purple hoodie I wear in the water. (The photo above is me like a normal person in a bathing suit just because I wanted a photo opportunity. Naturally, after three minutes of sun exposure, I got a rash, but the photo was worth it.) And so it’s a bit absurd that I love swimming and beaches more than I ever did, when a practical person might find a different kind of pursuit—badminton? But we make it work. We have a sun tent so I can beach all day and stay in the shade, and when I go to the beach I always bring a bathing suit to change into, because my lake water allergy kicks in when I sit around in wet bathing suits. (I know, I know. I am infinitely sexy.) And while this is inconvenient, the result is that I now have so many bathing suits. While we were away on holiday by a lake in the summer, I marvelled at the array of them drying on pegs in our cottage bathroom—I have so many bathing suits. Because I’m allergic to lake water, okay, but also because I am a swimmer. I am a swimmer.

And I love that, having so many bathing suits. Some of which look really good on me and others (see the purple one above: NOT FLATTERING) do not, but how I look is not even the point (although it certainly is in this stunning photo to the left), but what I can do: swimsuits are for swimming. I am a swimmer. And once upon a time I paid a lot of money for a bathing suit that made me feel good, and I know there are other women for whom bathing suit shopping is a form of torture, and some women who won’t appear in public in a bathing suit at all. Whereas I have a bathing suit bouquet. And as a woman on the cusp of being forty, I see this as an accomplishment I’m proud of, how it sets the kind of example I want to set for the two small women I gave birth to. An indication that I’m right where I want to be at this point in my life, a good and fortunate place.

And I love that, having so many bathing suits. Some of which look really good on me and others (see the purple one above: NOT FLATTERING) do not, but how I look is not even the point (although it certainly is in this stunning photo to the left), but what I can do: swimsuits are for swimming. I am a swimmer. And once upon a time I paid a lot of money for a bathing suit that made me feel good, and I know there are other women for whom bathing suit shopping is a form of torture, and some women who won’t appear in public in a bathing suit at all. Whereas I have a bathing suit bouquet. And as a woman on the cusp of being forty, I see this as an accomplishment I’m proud of, how it sets the kind of example I want to set for the two small women I gave birth to. An indication that I’m right where I want to be at this point in my life, a good and fortunate place.

A place which is, often, literally flying.