November 6, 2018

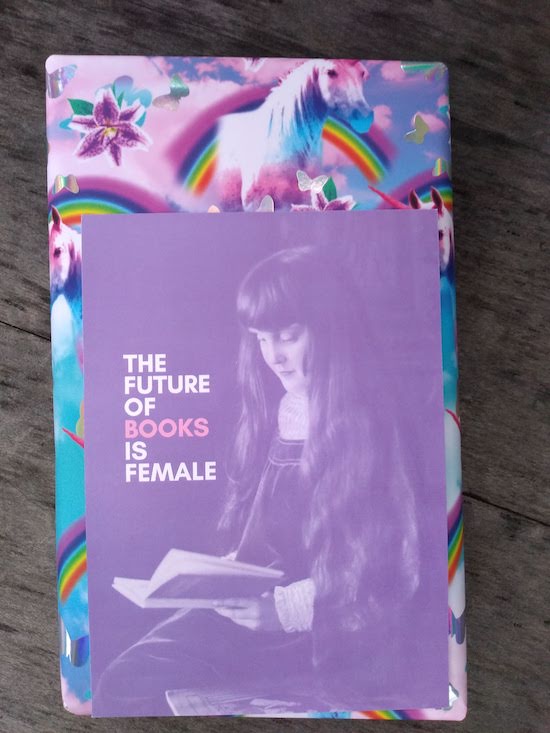

The Future of Books is Female

In this moment when so much seems dark, the light tends to shine even brighter, or maybe it’s just that I’m looking for it, but does the distinction even matter? It all began with a tweet thread, I think, when the editor of The Paris Review joined the parade of men who’ve lately been called out for sexual misconduct and when the editorial history of the magazine was being chronicled, one vital detail had gone amiss. “I’m going to show you how a woman is erased from her job,” the writer A.N. Devers tweeted, and proceeded to tell the story of Brigid Hughes, who’d succeeded George Plimpton at The Paris Review after Plimpton’s death, after working at the magazine for her entire career. But out of respect for Plimpton, Hughes was billed as “executive editor,” Plimpton remaining on the masthead. And then a year later Hughes was fired, and thereafter The Paris Review’s second editor and first female editor was written out of its history. Devers would eventually write this story into an essay published at Longreads.

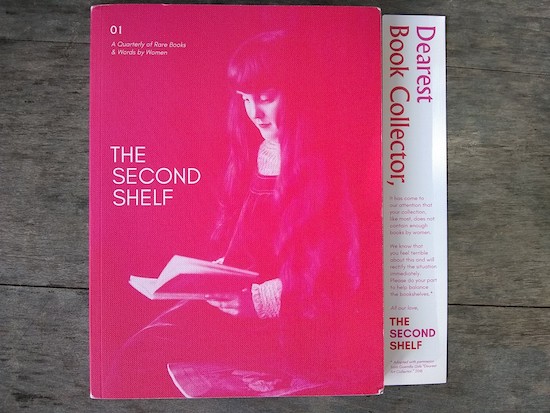

Plans for Devers’ Second Shelf Books venture had been in the works for a few years, apparently (and is just one of the many fascinating things that she’s been up to), but for me the link seemed quite direct to me from her work on re-establishing Hughes’ professional record to starting a business that champions under-appreciated books by women authors (“rare books, modern first editions, and rediscovered works…”), and I was so galvanized by her work on the former that I jumped on board to support the latter. I signed up for the Second Shelf Books kickstarter to support the project and receive a copy of their Quarterly, a gorgeously produced magazine that is a literary catalogue and a celebration of women’s writing at once—and then before time ran out upgraded my support so I would receive a surprise first edition from Second Shelf. And it has been a pleasure to watch from across the ocean as Devers’ vision has become reality, the funding drive a success, a profile in Vanity Fair among other coverage, and the online store expanding to be actual bricks and mortar.

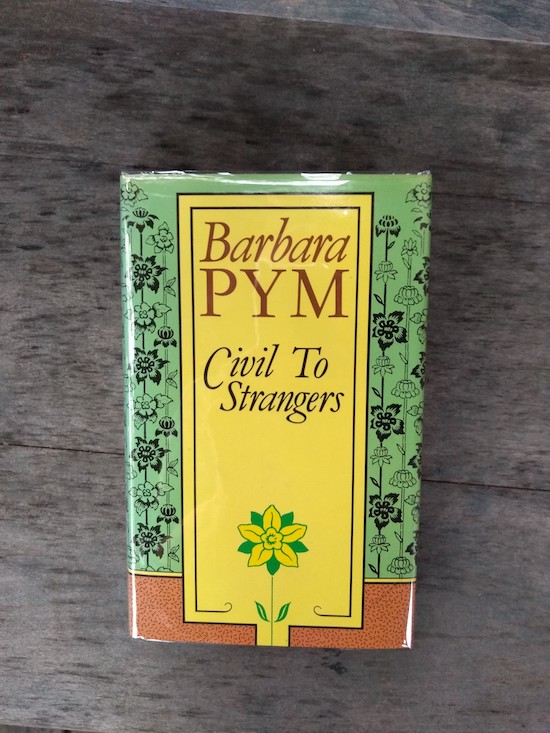

My copy of the Quarterly arrived a month ago, and I’ve deeply appreciated its aesthetic (marbled papers!), what it’s taught me about book collecting, and the writers I’ve been able to discover—for example, the first Black woman in South Africa to publish a novel was Miriam Tlali in 1975, with Muriel at Metropolitan. It has awakened my interest in book collecting for sure, and I’ve been pleased to discover I’ve already got a few first editions by women writers on my shelf, and now I’m on the look out for more—I found Carol Shields’ The Republic of Love at a used bookshop this weekend. It’s an opportunity, as Devers has explained, because books by women have historically been undervalued by book collectors (who’ve tended to be men), and therefore the investment is lower, but as more people begin to take notice, values will begin to rise. Or so it’s hoped, but regardless, I was overjoyed to receive my surprise first edition yesterday, carefully chosen after I’d completed a short survey online of my favourite authors. Wrapped in unicorn paper AND bubble wrap, so my children were squealing, and I got in on it too when I realized which book I had gotten. The hardcover Barbara Pym Civil to Strangers, a collection of stories and fragments published after her death. Could it be more perfect? And who knew there was a whole other reason to buy books that I hadn’t even considered? But I’m hooked now, and excited for the future of Second Shelf Books.

November 2, 2018

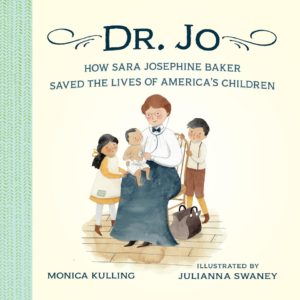

Dr. Jo, by Monica Kulling

With her latest book Dr. Jo: How Sara Josephine Baker Saved the Lives of America’s Children, Monica Kulling continues to write fascinating (and often feminist!) biographies of remarkable figures who should be better known. We were huge fans of her Spic & Span, a biography of Lillian Gilbreth, who was not only the real-life mother of the Cheaper By the Dozen family, but she was also an efficiency expert, author, psychologist, industrial engineer, and inventor of the shelves inside your fridge door, the electric mixer AND the foot-pedal garbage can, which might make you wonder why all the books in the world aren’t about Lillian Gilbreth. But in the meantime, Dr. Sara Josephine Baker is worthy of a story of her own.

With her latest book Dr. Jo: How Sara Josephine Baker Saved the Lives of America’s Children, Monica Kulling continues to write fascinating (and often feminist!) biographies of remarkable figures who should be better known. We were huge fans of her Spic & Span, a biography of Lillian Gilbreth, who was not only the real-life mother of the Cheaper By the Dozen family, but she was also an efficiency expert, author, psychologist, industrial engineer, and inventor of the shelves inside your fridge door, the electric mixer AND the foot-pedal garbage can, which might make you wonder why all the books in the world aren’t about Lillian Gilbreth. But in the meantime, Dr. Sara Josephine Baker is worthy of a story of her own.

“People called Sara Josephine Baker a tomboy,” the book begins. “Jo did things that the quiet and polite girls of her day did not do…” From playing sports and skating on the Hudson River, to attending medical school—Jo’s interest in being a doctor underlined by the deaths of her father and brother from typhoid fever caused by a hospital dumping sewage in that same river. The importance of public health was also made apparent to Jo through these tragedies, and once she became a physician she realized that working as a health inspector would permit her to make an even greater difference. Kulling shows Jo working in Hell’s Kitchen in New York City, where disease spread quickly through tenement housing. And while the illustrations are cheerful and bright, the text doesn’t shy away from the realities of poverty and deprivation—Dr. Jo is called to a family whose baby dies of heatstroke, and another baby she visits has become blind from drops used to clear bacteria from its eyes. Kulling walks a perfect balance between message and story to deliver a picture book that readers of all ages will enjoy.

Kulling shows how Dr. Jo started the practice of licensing midwives to make births safe, organized stations where children could access clean milk, solved the problem of eye drops being contaminated with bacteria, and designed infant clothing that made for better temperature control. “Dr. Jo understood the connection between poverty and illness. Throughout her life she worked tirelessly to improve the health of women and their children in New York and other big cities.”

November 1, 2018

Why I Love Literary Prizes/ Why I Don’t Care About Literary Prizes

I couldn’t decide whether to call this post, “Why I Love Literary Prizes,” or, “Why I Don’t Care About Literary Prizes,” which one would garner the most outrage and clicks, and it says something about literary prizes that both perspectives are controversial. And they’re both true, in my case. I don’t care about literary prizes, which is why I love them. Although I’m not saying that if you gave me a literary prize I wouldn’t love them even more, of course—MY LITERARY PRIZE DOOR IS ALWAYS OPEN…especially because I broke my phone and now it no longer types As or exclamation marks, and if you gave me a literary prize with cash value (or a gift certificate to Wind Mobile) I would be able to afford to buy a new one.

But in the meantime, I will tell you that I used to care deeply about literary prizes once, because as a reader they were my gateway into feeling like part of a wider literary community. I read that book that won the Giller Prize by the doctor who met Margaret Atwood on a cruise ship—Vincent Lam! Although I can’t remember what the title was. I also recall being ecstatic when Elizabeth Hay’s Late Nights on Air won the Giller Prize, because I really loved that book when I first read it. It felt good to be part of a thing that everyone else was doing, and to receive reading recommendations, because this was about ten years ago, which is when my bed wasn’t a mattress on top of a perilously toppling pile of books stacked onto infinity.

But then I started to become more defined as a reader, and have a deeper knowledge of “the CanLit scene” and started paying attention to things like small presses vs. big presses, which meant that literary prize culture started to seem annoying—because these books were supposed to be celebrating “the best,” but I wasn’t sure they were doing the greatest job of that. This was also before I discovered that “the best” is not a thing, and that tastes (and juries) are subjective. But before that discovery, prizes seemed frustrating and useless and occupied so much real-estate literary-coverage wise that I’d rather ignore them than pay attention, because I don’t get off on being angry for recreational purposes. If a book I liked won the Giller Prize (Hello, Hellgoing!), well then, hurray. But I was certainly not going to read a book just because it had a sticker on it, and definitely not if it was a book that I had no intention of reading in the the first place.

Another reason I went off literary prizes was because I’d have to listen to writers moan about not winning them, and also hear others declare that winning such prizes was “humbling” (which makes no sense whatsoever). The collective malaise that hits Canadian authorial communities on the days when shortlists are announced is even more annoying than a poet who reads for thirty-five minutes—it makes me want to all-caps scream, GET OVER YOURSELVES. Yes, you worked hard on your book, and yes, you would have wanted this success for your publisher who put all his faith in you and your book, and who wouldn’t want to win hundreds of thousands of dollars (or a Wind Mobile gift certificate, even). But I have wanted a great deal many things in my life that I never got, and so have you, and one upside to the downsides of being a woman is that we rarely ever feel entitled to anything, including the things we’ve earned, so your assumption that you belonged on a prize list is kind of weird to me and I just think you should stop it, and go out for a beer and cry with your best friend, and them move on with things. It’s going to be fine.

I am also an author of commercial fiction, which never gets nominated for literary prizes anyway, which makes the whole equation easier for me. Although I will admit that I was fully prepared to be UNEXPECTEDLY nominated for the Giller Prize last year for my SUBTLY BRILLIANT UNDERRATED BOOK, and I’d been practicing both feigning surprise AND being a dark horse, and when the call never came, all that practice was for nothing, but I am an author, so certainly that wasn’t my first disappointment. All of us in this area are nothing if not well-trained.

When I am not busy being a non-award-winning author with a broken phone (VERY GLAMOROUS), I am fortunate to earn a living as editor of the Canadian books website, 49thShelf, and it was through this role that my appreciation for literary prizes began to return—for practical reasons, mostly. Because it’s part of my job to switch up featured books and lists on our homepage every week, and it’s a task that’s very easy this time of year as prize lists and award winners are being announced by the day—just this week, The Taste Canada Prizes, the Governor General’s Literary Awards, the Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards. List after list, some with the usual suspects, but others with titles readers might not have heard of yet. And while not all prize lists lead to a huge bump in sales, I still love the way these lists shine a spotlight on titles and place them in a broader literary context. I love anything that gives us a reason to talk about a book—to make a book news, to tell a bookish story, to get us a little more excited about books. The actual awards might not be hugely meaningful (apart from a few with big cash prizes and sales bumps), but the books themselves mean an awful lot, and anything that gives even a few readers the chance to discover that is perfectly fine with me.

October 29, 2018

More Fun Things

Last weekend, I had the great pleasure of returning to the Stratford Writers Festival, where I moderated a panel about women’s experiences with Sarah Selecky, Andrea Bain, and Emily Anglin, and it was wonderful. I still remember the first time I was asked to moderate anything, years ago, and how I accepted the job because I thought it was the kind of thing I’d really like to do, although I wasn’t sure I’d be very good at it—and I wasn’t. But over the years, I’ve become comfortable with public speaking and confident about my own skills as a reader, to the point where I’m a kickass moderator and I know it, and I love it. It was a real pleasure to be part of this event.

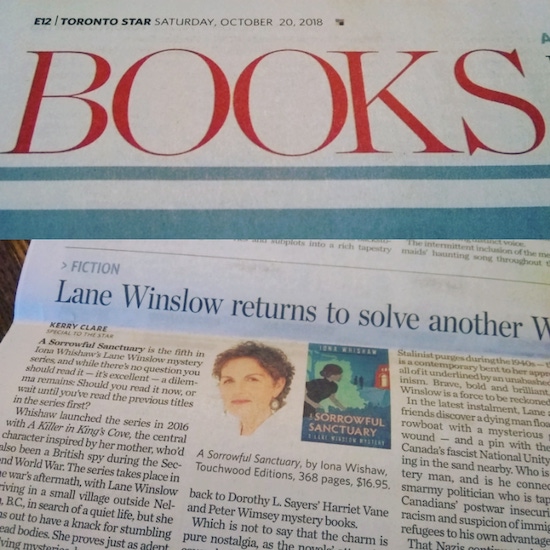

That same weekend, I had the joyful experience of my review of Iona Whishaw’s A Sorrowful Sanctuary appearing in The Toronto Star’s venerable books section. So nice too that Whishaw’s all too timely historical novel gave me an excuse to be calling our shady nationalist politicians and Nazis in the media. ‘“I suppose I’m simply naïve,” [Lane] explains. “I want all my Nazis parceled up and put on the shelf of history after all our hard work in the war. I didn’t expect to find them here.”’

And this weekend, I’m off to Sudbury for the Wordstock Sudbury Festival. On Saturday morning, I’ll be appearing on a book industry panel with Hazel Millar and Holly Kent, and later that afternoon representing Mitzi Bytes with Margaret Christakos and Diane Schoemperlen, and I’m really looking forward to it.

October 25, 2018

Radiant, Shimmering Light, by Sarah Selecky

Last week, I reread Sarah Selecky’s debut novel, Radiant Shimmering Light, before her panel at the Stratford Writers Festival, which I was moderating. I’d first read the novel back in the winter as a manuscript, and found it strange and fascinating. “Fresh and original, Sarah Selecky’s novel clever satirizes our insta-world but also takes its characters seriously enough to give them an ending that’s moving and transcendent,” so my blurb went. “Deceptively light,” was another blurb, by Lisa Gabriele, and it’s exactly right and what makes Radiant Shimmering Light such a challenging novel. Challenging not in the usual ways—no paragraph breaks or all the characters have names that are adverbs—but instead for how it’s situated in a space between. It’s a satire that takes its characters seriously. This is not Lucky Jim, I mean, absurdity spiralling down into disaster. Which is not to say that book isn’t funny—there is a character called Knigel, for starters. Lifestyle blogs are beautifully skewered by the main character’s friend who runs a blog called “Pure Juliette”, and who guides her followers with cute ways to freshen up their Easter baskets “with things you already have at home! It’s amazing what you can do with silk flowers, a nip of floral tape, and spray glitter.” The novel’s protagonist, Lilian, attempts to self-actualize alongside the personal development gurus she follows online, whose entrepreneurial sensibilities resonate since she runs her own business painting pet auras. It’s all completely ridiculous—someone else makes “consciousness truffles,” whose gluten-free batter is infused with monk chats. Characters attempt mindfulness by meditating on their cell-phone chimes. The perfect set-up for a joke, all of it, but that would be far too easy. And this is where the challenge comes in.

Last week, I reread Sarah Selecky’s debut novel, Radiant Shimmering Light, before her panel at the Stratford Writers Festival, which I was moderating. I’d first read the novel back in the winter as a manuscript, and found it strange and fascinating. “Fresh and original, Sarah Selecky’s novel clever satirizes our insta-world but also takes its characters seriously enough to give them an ending that’s moving and transcendent,” so my blurb went. “Deceptively light,” was another blurb, by Lisa Gabriele, and it’s exactly right and what makes Radiant Shimmering Light such a challenging novel. Challenging not in the usual ways—no paragraph breaks or all the characters have names that are adverbs—but instead for how it’s situated in a space between. It’s a satire that takes its characters seriously. This is not Lucky Jim, I mean, absurdity spiralling down into disaster. Which is not to say that book isn’t funny—there is a character called Knigel, for starters. Lifestyle blogs are beautifully skewered by the main character’s friend who runs a blog called “Pure Juliette”, and who guides her followers with cute ways to freshen up their Easter baskets “with things you already have at home! It’s amazing what you can do with silk flowers, a nip of floral tape, and spray glitter.” The novel’s protagonist, Lilian, attempts to self-actualize alongside the personal development gurus she follows online, whose entrepreneurial sensibilities resonate since she runs her own business painting pet auras. It’s all completely ridiculous—someone else makes “consciousness truffles,” whose gluten-free batter is infused with monk chats. Characters attempt mindfulness by meditating on their cell-phone chimes. The perfect set-up for a joke, all of it, but that would be far too easy. And this is where the challenge comes in.

In our conversation on Saturday, I asked Selecky about this, about the appeal of the narrative space-between realism and satire. Where, as she puts it, the reader is forced to sit in discomfort. But the discomfort is the very point, particularly at a moment when people’s refusal to be uncomfortable has led to dangerous social and political polarization. She talked about how she started with the idea of writing the novel as straightforward satire, but the satire was mean and shallow and she wanted to write something deeper than that. And so Radiant Shimmering Light was born, satire from the inside. She talked about the problematic aspects of online women’s empowerment culture—commodification, cultural appropriation, issues around personal branding—and yet there is something fundamental to the messages as well, messages that do many women a lot of good. “The challenge is to hold both realities at once.”

Considering the ways that books marketed to women are undervalued in a literary sense, it’s not shocking to me that a book about the ways that women are marketed to might not receive the credit it deserves as a sophisticated and multi-faceted novel with literary value. I recall an interview with a Scotiabank Giller jury from a previous year who noted that he’d been able to dismiss certain books out of the gate for being “problematic in their sensibility,” whatever that means, and it’s true that a reader’s first encounter with Lilian Quick might not create a great appreciation for her as a literary character or for the novel as a literary project. Deceptively light, remember? This is a novel about a woman who is silly, and it seems straightforward that such a thing could be so one-dimensional—but this book isn’t. Selecky takes light and lightness, and works it into a novel that is subtly profound. The subtlety not undermining the profoundness, in fact underlining it. The detail is fine, and you have to read closely to see.

I was pleased to see that this year’s Governor General’s Award finalists for fiction includes Sarah Henstra’s The Red Word, a book that left a huge impression on me when I read it, and I read it at the same time I was reading Radiant Shimmering Light. A books whose power is as brutal and difficult as Selecky’s is subtle, but I still see many connections between them. In our Q&A, Henstra talked about her inspiration from a Susan Sontag quote about good fiction existing to “enlarge and complicate—and, therefore, improve—our sympathies. They educate our capacity for moral judgment.” Henstra shares how she had difficulty finding a publisher because her book too is situated in a space-between and didn’t offer easy answers to questions like, “So what’s the takeaway for feminism?” Both are novels situated in discomfort, books that complicate instead of resolve, books that challenge their readers as they offer compelling reading experiences at once. Serious books that don’t wear their seriousness on their jackets/sleeves, and with women at their centres, so sometimes, to some readers, it’s almost like they never happened at all.

October 23, 2018

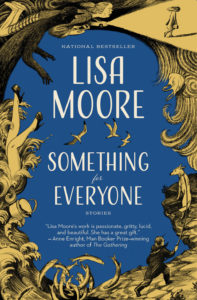

Something for Everyone, by Lisa Moore

My first Lisa Moore memory is visceral—it was 2005 when I was in graduate school and my husband had recently immigrated and wasn’t eligible to work so we had no money, but then someone gave me a gift certificate for a bookshop, and I bought Alligator, which read like nothing I’d ever read before. So absolutely crackling with life, and the dexterity of the language, and the way she makes every sentence full of twists and turns, which makes work to follow, but oh, the rewards. I loved Alligator; and then I loved February, so much, which inspired one of the best literary essays I’ve ever written: “Women’s literary fiction” is often distinct from literary fiction in general, either because it reads as such (with the squirting nipples, breaking water and placenta on a plate—if a man had written this book it would be surprising), or because it’s come into the world via a woman’s pen and is therefore received differently from literary fiction in general (which is to say, men won’t read it). Sometimes both of these things are true, sometimes one is, and sometimes neither.”

My first Lisa Moore memory is visceral—it was 2005 when I was in graduate school and my husband had recently immigrated and wasn’t eligible to work so we had no money, but then someone gave me a gift certificate for a bookshop, and I bought Alligator, which read like nothing I’d ever read before. So absolutely crackling with life, and the dexterity of the language, and the way she makes every sentence full of twists and turns, which makes work to follow, but oh, the rewards. I loved Alligator; and then I loved February, so much, which inspired one of the best literary essays I’ve ever written: “Women’s literary fiction” is often distinct from literary fiction in general, either because it reads as such (with the squirting nipples, breaking water and placenta on a plate—if a man had written this book it would be surprising), or because it’s come into the world via a woman’s pen and is therefore received differently from literary fiction in general (which is to say, men won’t read it). Sometimes both of these things are true, sometimes one is, and sometimes neither.”

Fittingly, the next time I’d read a Lisa Moore book, I would be in labour, reading the first half of Caught while having contractions in my bathtub—but after the baby was born, unfortunately, I was never able to pick it up again for reasons of association. But I loved Flannery, her YA novel that came out a couple of years ago. Which brings me to her latest, Something for Everyone, which was long listed for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and is one of the best books I’ve read this year. And so yes, you could say I’ve measured out my life in Lisa Moore books indeed.

Something for Everyone is particularly good, however, although I’m not sure it’s really for everyone. First, because short story collections are hard to hold, for readers and reviewers alike—several stories in this collection have the breadth of a novel. Bang for your buck, for sure, but it doesn’t make for easy reading, simple to dip in and out of. These are stories that demand patience and close attention, careful reading. Oh, but the rewards come back tenfold. The very first story, “A Beautiful Flare,” takes place over a couple of minutes in a mall shoe store, the most unfathomable love triangle, but how Moore manages to fathom it, the noise and the chaos and the perilousness of stacked boxes, and “the new heat-sensing Brannock foot measurer…the first innovation to the original design since 1928.” There is something in the way that Moore must see and therefore writes about colour and light, as though through a prism, and the connections she makes, impossible links that fit perfectly, and for just a moment or two, this broken and jumbled up world of ours nearly makes perfect sense. How does she know? About the Brannock foot measurer, and everything, I mean. It must be the most extraordinary way of paying attention, and as a writer it fills me with awe. As a reader it fills me with gratitude.

These are stories born in a time of economic austerity and precarity. Jobs are lost, positions are eliminated, and someone gets swindled in a shady condo deal. Sex workers live in threat of violence, and other workers think about retraining. Old lovers meet in a grocery store entrance in the middle of a blizzard: “The plastic bags flutter in the wind and the doors shut again, leaving us in a vacuum, still as a snow globe.” In “The Viper’s Revenge,” a woman attends a library conference in Orlando two weeks after the Pulse Nightclub massacre, and how her story gets wound up with that of a pool cleaner, in the most tender, perfect, heartbreaking way. It was all very hard to read, and then a story from the perspective of Santa Claus (really) lights up the darkness.

The final story is “Skywalk,” which is just under a third of the book, and is worth the price of admission, really. Taking place over three years in St. John’s with two young people who make a brief connection as a serial rapist stalks the city, and then find each other again later. A dark undercurrent and sense of danger infuses the story with an incredible momentum, and it’s positively gripping, just absolutely exactly what it should be, real as life and masterfully crafted at once.

October 19, 2018

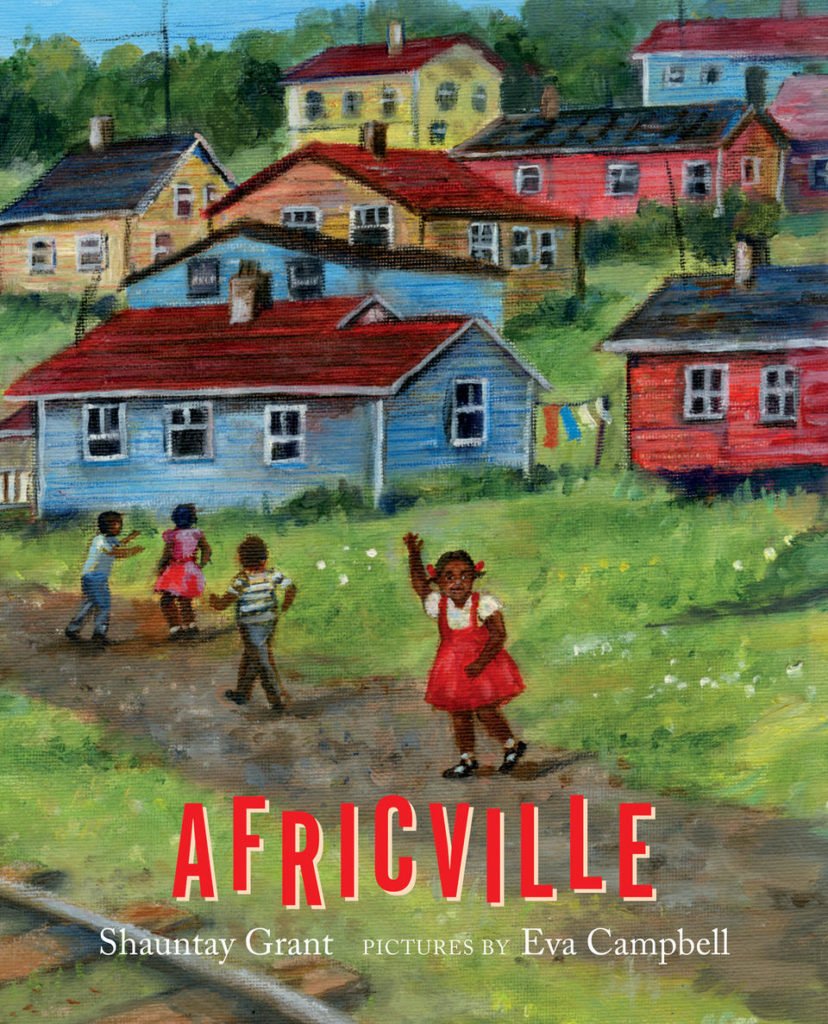

Africville, by Shauntay Grant and Eva Campbell

I am generally impressed with the search function for my online photos—if I search for “playground,” “Kensington Market,” or “bookstore,” it tends to have an uncanny sense of what I’m looking for, although it still has trouble telling the difference between a cup of tea and bowl of soup. But a search for “Africville” turned up nothing, a location Google didn’t recognize—which meant I had to go back into the archive and find the photo myself, the one of my children in front of the Africville Museum on our trip to Nova Scotia in 2017.

Which actually didn’t surprise me in the slightest, the history of Halifax’s historic Black community being one that’s not much about erasure, never mind that many of its residents could trace their roots back to the arrival of Black Loyalists in Canada during the American Revolutionary War. But while the community thrived in many ways, Africville’s residents never receive the same services as other taxpayers in the Halifax area, such as running water or sewage systems, and the municipality also saw fit to zone a garbage dump and slaughterhouses as its neighbours–all of which meant that when it became fashionable to condemn this historic Black community and recommend its demolition, there appeared to be plenty of reasons to support this action, and in the 1960s—against opposition—residents were moved out and the community was torn down.

On the site now, a replica of the community’s church has been built as a museum, following the declaration of Africville as a National Historic Site of Canada in 2002. Our visit in 2017 was moving and informative, with a great scavenger hunt that got my children involved and engaged with the exhibits, and prompted important conversations about systemic racism and its historic legacies. But while there were books in the giftshop, there were no picture books about Africville exactly. Instead, we got Up Home, a beautiful book about another Nova Scotian Black community called North Preston, written by poet Shauntay Grant—whose The City Speaks in Drums we also picked up somewhere along the way, a perfect Halifax souvenir. All this meaning that I’ve been really looking forward to Grant’s latest release, Africville, a finalist for this year’s Governor-General’s Award for Children’s Literature, lyrically resonant and stunningly illustrated by Eva Campbell.

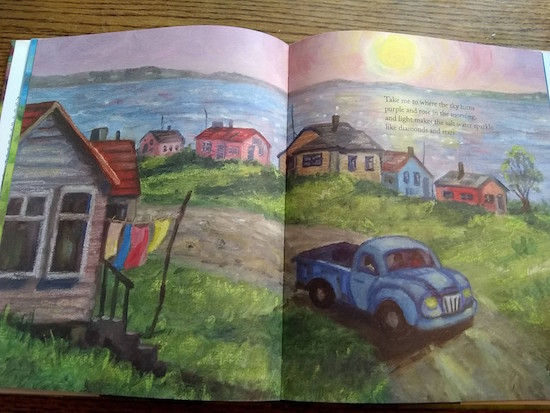

“Take me to the end of the ocean,” the book begins, “where waves come to rest and hug the harbour stones.” Africville reimagined in Campbell’s illustrations, oil and pastel on canvas, brightly coloured houses beside the bright blue sea. Blueberries growing on the hill, smells of apple pie and blueberry duff drifting from the kitchens. Football, rafting, and warm summer nights, “down at Kildare’s Field,/ a bonfire burning red/like the going-down sun.”

“Where the pavement ends and family begins.”

Through her story, Grant shows the resilience of Halifax’s Black community who wasn’t about to let their history disappear, and founded an annual Africville reunion festival in 1983, which continues years later and helped lead to the historic site declaration decades later. The rainbow houses are gone, but we see a stone marking the names of community families, and celebrations and singing inside the festival tent. “…where memories turn to dreams,/ and dreams turn to hope,/ and hope never ends. Take me…to Africville.” A history that’s erased no longer.

October 16, 2018

The babysitter is not here.

I need a babysitter. Literally, yes, but also more figuratively too, and I’m having trouble finding the one I need, because teenage girls are so much younger now than they used to be when I was a small child, when I regarded babysitters with the reverence Dar Williams articulates exactly in her song, “The Babysitter’s Here.” A babysitter like Elisabeth Shue in Adventures in Babysitting, pretty much the archetypal babysitter. But if you recall, Shue’s “Chris Parker” character was only available to babysit because she’d just had a date cancelled by her jerk boyfriend—in reality, seventeen-year-old girls are not very interested in babysitting at all. Eleven and twelve-year-old girls girls are actually where it’s at, babysitting wise, but then it’s the same thing that all of us had to deal with when we examined The Babysitters Club series with a critical eye, and realized the girls in the club were just children. No offence to Mallory Pike, but I’m not totally comfortable leaving my children in your care (and besides that, you have a nine o’clock curfew).

I need a babysitter. Literally, yes, but also more figuratively too, and I’m having trouble finding the one I need, because teenage girls are so much younger now than they used to be when I was a small child, when I regarded babysitters with the reverence Dar Williams articulates exactly in her song, “The Babysitter’s Here.” A babysitter like Elisabeth Shue in Adventures in Babysitting, pretty much the archetypal babysitter. But if you recall, Shue’s “Chris Parker” character was only available to babysit because she’d just had a date cancelled by her jerk boyfriend—in reality, seventeen-year-old girls are not very interested in babysitting at all. Eleven and twelve-year-old girls girls are actually where it’s at, babysitting wise, but then it’s the same thing that all of us had to deal with when we examined The Babysitters Club series with a critical eye, and realized the girls in the club were just children. No offence to Mallory Pike, but I’m not totally comfortable leaving my children in your care (and besides that, you have a nine o’clock curfew).

But when I was a child and it was 1985, the seventeen and eleven were indistinguishable from my vantage point, and the babysitters all had feathered hair, and exotic accoutrements like braces and acne. Dangling earrings. To me, they were all beautiful, and fascinating, and a window onto my own future as an adolescent, although I would never be as amazing as they were. (It is likely that they were also not as as amazing as they were.) My babysitters were basically Nancy from the Netflix series Stranger Things, who (along with Winona Ryder) was mostly everything I actually liked about Stranger Things, pure babysitter nostalgia. They had names like Bonnie-Ann, and Sarah-Michelle, and Lisa and Heather. One time we even had one who was actually called Nancy, who lived in a townhouse near Oshawa Centre, and I must have come along when my parents picked her up or drove her home, because I think about her every time I drive down Dundas Street in Whitby, and it’s possible that I only ever knew Nancy for a couple of hours in my entire life.

But there is a kind of presence that babysitters possess, an easy authority. No babysitter ever had to yell at us, because my sister and I were in love with all teenage girls and would have done anything they asked of us. My one episode of defiance came about when my babysitter Lisa had her boyfriend over while she was babysitting us, and I was really uncomfortable with his presence, because I was aware that this was a transgression, but also I didn’t like him, and he was distracting our babysitter from lavishing her attention on us. So after I’d been put to bed, I called downstairs to Lisa and her boyfriend that my parents’s car had just returned to the driveway, even though it hadn’t, and she had to get rid of him out the side door fast. I don’t remember if she brought him back once it was clear that I was lying, or if she demonstrated her anger toward me, but I do know that that was the last time Lisa ever babysat at our house.

But there is a kind of presence that babysitters possess, an easy authority. No babysitter ever had to yell at us, because my sister and I were in love with all teenage girls and would have done anything they asked of us. My one episode of defiance came about when my babysitter Lisa had her boyfriend over while she was babysitting us, and I was really uncomfortable with his presence, because I was aware that this was a transgression, but also I didn’t like him, and he was distracting our babysitter from lavishing her attention on us. So after I’d been put to bed, I called downstairs to Lisa and her boyfriend that my parents’s car had just returned to the driveway, even though it hadn’t, and she had to get rid of him out the side door fast. I don’t remember if she brought him back once it was clear that I was lying, or if she demonstrated her anger toward me, but I do know that that was the last time Lisa ever babysat at our house.

The most magical babysitter ever (“She’s the best one that we ever had…”) was Sarah Michelle, who was so pretty (“pretty” was an essential quality for babysitters to have, as far as we were concerned) and who played with us, which was novel, and she became a kind of legend (I think we built something out of a cardboard box) and I remember too that she came to babysit us again after a break, as she wasn’t magic anymore and didn’t play with us at all. Possibly she’d just turned seventeen and had just started had a date cancelled by her boyfriend, but I recall the disappointment viscerally, one off my earliest heartbreaks. The unsustainability of superstar babysitting, for most ordinary people, is an unfortunate reality. Except for a select blessed few among us, the novelty of time spent in the presence of small children is something that wears off fast.

Which is a fitting place to transition to my own experiences as a babysitter, and the children I was caring for factor very little in my memories of being a babysitter—and how Bonnie-Ann, Sarah Michelle, Lisa and Heather probably don’t think of me at all. My own babysitting memories are set in the 1990s with City TV late night movies on, most notably the 1982 film Cat People, about people who turned into monstrous black panthers, and which was so terrifying that I was afraid even to get off the couch and go into the kitchen and eat all of the pickles in the fridge leaving behind bottles of brine, which was my usual tactic as a babysitter. When I wasn’t eating all their chips and ice cream, that is. “Help yourself to anything in the kitchen,” was a dangerous offer to me in 1994, and many of my babysitting clients would live to regret it. You’d think they’d even stop hiring me, with thoughts toward conserving the grocery bill, but then babysitters are hard to come by, a most precious resource. You take what you can get.

October 15, 2018

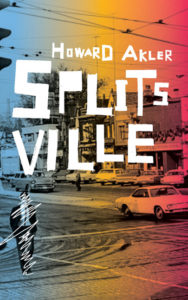

Splitsville, by Howard Akler

Howard Akler packs a lot into a scant 119 pages in Splitsville—a neighbourhood, a city, a legendary municipal battle that’s nearly fifty-year-old. History and geography. The beginning, middle and end of a love affair. Words I didn’t know the meanings of, and which made me pull out my underlining pen instead of rolling my eyes in frustration: aniline; exophthalmic; badinage; ulna; oppugnant.

Howard Akler packs a lot into a scant 119 pages in Splitsville—a neighbourhood, a city, a legendary municipal battle that’s nearly fifty-year-old. History and geography. The beginning, middle and end of a love affair. Words I didn’t know the meanings of, and which made me pull out my underlining pen instead of rolling my eyes in frustration: aniline; exophthalmic; badinage; ulna; oppugnant.

And a mystery: Hal Sachs had run a used bookstore on Spadina Avenue as the debate over the Spadina Expressway was heating up, and he falls in love with Lily Klein, fired from her job teaching civics at Harbord Collegiate for activism. (“The point is: people are really steamed. They’re organizing. That’s the true meaning of democracy. It’s not as simple as majority rules. It’s more about voice, about speaking up and about the city learning to listen to other points of view.”)

On the day before the final decision about the Spadina Expressway is brought down, Hal Sachs disappears. Decades later, his nephew (“Aitch Akler:” this is autofiction of a sort, as I understand it, except it’s not exceptionally annoying, distinguishing this novel in the genre) is expecting his first child, and trying to piece together fact and fiction to understand what happened to his uncle, and what happened to the city whose streets and sidewalks he navigates on a peripatetic journey into the past and into the future at once.

A huge part of my passion for this novel is personal: the characters trace the same sidewalks I walk every day, sidewalks that wouldn’t even exist in the Spadina Expressway plan had not been thwarted—because otherwise my neighbourhood would have been demolished. Every day I walk up Robert Street north of Sussex, a playing field because the houses had been bought up and torn down to make way for the expressway that never arrived. On Saturday, we went out for lunch in Chinatown because Splitsville had made me hungry. I know these streets. But it’s more than that too, this novel fulfils a yearning I’ve had for real and deep conversations about civic engagement at a moment when our democratic rights as Torontonians have just been trounced upon a by spiteful and reckless provincial government. What does it mean to fight for something? Does it matter if you win or lose?

I think you need not be a person who cross Spadina Avenue at least six times daily or be someone whose voting rights have recently been undermined to appreciate Splitsville, however. My passion is only partly personal, and is also about the novel’s attention to language, its literary references, its bookstore setting, the subtlety of its plot and pacing, its absolutely perfect conclusion, and the mystery at its core, questions without answers. I was on Page 93 of the book when I went online and ordered another copy to mail to a friend, which is some kind of endorsement for sure. And now that I’ve read to the end, I want to give a copy to everyone.