January 24, 2019

One Strong Girl, by Lesley Buxton

“It’s not the violence [of murder mysteries] I’m attracted to. It’s the grief. These mysteries offer me the truest reflections of my own feelings. Unlike ‘based-on-true-life’ stories about children who die, there are no grand epiphanies, no resolution all beautifully wrapped up. In mysteries the characters mourn unapologetically, their lives narrow. I’m comfortable in this milieu. Here nobody ever says, ‘It all happened for a reason’ or asks of the mother to be thankful her child is no longer in pain. Here everybody recognizes that it was better before.”

As I finished reading Lesley Buxton’s memoir, One Strong Girl, last night, I started thinking about birth stories, and how many of these I’ve read over the years. And about the parallels between these stories and the one Buxton shared in the section of her memoir called “So Eden Sank,” the story of the end of her teenage daughter India’s life. Beginning with arrival at the hospital (after six years of India’s illness, which baffled doctors at every turn), and then a move to a hospice where the family settles into their room there, and people come and go, and time moves at the most peculiar pace, and it seems like nothing and everything is happening at the same time as they all move toward a moment that will shatter the universe forever.

But mothers are not encouraged to share the stories of their children’s deaths as they are to share the birth stories, because most of us would prefer to go on imagining that such stories rarely happen. “Nobody wants to visit the place where I live,” writes Buxton, but she’s telling her story anyway so we can at least peek inside the windows. And she’s telling it to put the pieces together to make something of so much loss, I suppose. To give other grieving parents a sense of the path that lies before them, and as a testament to the spirit that was India—and Buxton’s abundant love for her daughter infuses every single word in this beautiful book.

Mother is both a verb and noun, and how do you do either once your child has died? This question is one that Buxton writes her way toward an answer to in One Strong Girl, a raw and heart-wrenching memoir of the kind of loss about which most of us would declare, “I just can’t imagine.” But we can, and Buxton invites us to. It’s not a linear narrative, but then it would not be real if it was. Beginning with a journey to Japan, which had been India’s fascination, and Buxton and her husband are bringing beads that hold India’s cremated remains, beads that they’ve been leaving behind at various locations that would have meant something to their daughter.

The next section outlines the beginning of India’s symptoms at age 10, mysterious falls and small seizures. In “Motherland,” Buxton writes about her own relationship to motherhood, and how complicated it is now that her daughter has died. (Read an adapted excerpt from this section at Todays Parent.) In “A Culture of Illness,” she goes through the 513 pages of India’s medical records, and tells the story through that lens, and how those records accord with her own memories of the experiences of the records track.

The next section is about how India’s illness and death changed Buxton’s relationship with her sense of home, and with her home itself. She writes about her teenage daughter’s bedroom, which is the most incredible kind of eulogy, and provides the reader with a strong sense of the person that India was. She continues with sections on India’s increasing decline, of her death, of where she and her husband are now—though all these sections keep circling backwards, looking behind, as you would too if the alternative was envisioning a future without your child.

It’s a finely wrought and beautiful book whose only flaw is that some of its rawness extends to its copy editing. But I really do love the rawness of he form itself, Buxton’s generosity and candour in sharing these terrible, painful, beautiful moments—all that love. As much a story of life as all the others we tell about our children are, and wholly deserving of a place in the parenthood canon.

January 23, 2019

We Hold Each Other Up

I like people in theory, but I have to tell you that in practice, I find a lot of them kind of annoying. Which makes me despair sometimes, because this is a political moment in which solidarity, allyship, and cooperation have never been more necessary. And what can you do at a moment like that when you’re kind of a misanthrope? Which is overstating it a bit, I realize. People are fine, but it’s not like I want to invite every single one of them over for dinner, you know? I’d rather read my book than chat to a stranger on the subway. I’ve unfollowed people on social media for being on a juice cleanse. I don’t want to deprive anyone of their juice, but I reserve the right to not to have to hear about it.

So I felt a bit strange about the Women’s March held in Toronto this Saturday, kind of inauthentic as a political person, the kind of who has a pot of chilli perpetually simmering on the stove and everybody is welcome at her table always. I feel uncomfortable aligning myself with political movements, with partisanship, even though I realize that failing to understand that politics is everything has never ever changed the world. I still resist the idea of chanting in a crowd of people, scripted call and responses. Even though I know that such noise can be revolutionary, and there is so much that really has to change. I do believe that this is a historical moment in which it’s necessary to declare what side you’re on, and I know what side I’m on. As per the sign I carried on Saturday, I marched for midwives, Black lives, clean water, Indigenous rights, sex-ed, public schools, for teachers, for the environment, for justice, and so much more. This is my feminism. I was there for my city, my province, my country, for my daughters. (And so grateful to the people who did the work and made the march happen, who were too busy with boots on the ground to be hemming and hawing about simmering chilli.)

It was a joyous occasion, albeit one held in a snowstorm. But we were prepared with multiple pairs of pants, and scarves plus neck warmers, and before we marched, we had breakfast at Rebecca’s house, where she had poster-making supplies, and we all got to work. (Because fighting the patriarchy is more fun with friends.) We arrived to hear the last few speeches, and then to join the parade up University Avenue to Queen’s Park, snow piling on everybody’s hats and heads. I pulled up my hood with its furry trim, and loved the cocoon of it. That I couldn’t properly hear or see what was going on around me (hoods are the enemy of peripheral vision), and everybody else was tucked inside their own hoods, each of us in our separate warmths, and yet moving all in the same direction together.

And it was that simple. We didn’t need to have chilli. At the end of the march, we’d all go our separate ways, most of us on public transit. But the march was a reminder and a commitment to the fundamental ways we are all of us connected whether we want to be or not, however uncomfortable it makes us sometimes. Because people aren’t easy, but people are the project, the point of it all. We don’t all have to be friends, but we have a responsibility to still care for each other, to listen to each other (which is not the same thing as having to agree). Because, as Iris’s sign said, riffing off a book we love, We Hold Each Other Up. And it will never not be interesting.

January 22, 2019

On Revising—or How I Learned to Spell ‘Excruciating.’

The title of this blog post is a lie, because I still don’t actually know how to spell “excruciating.” When I initially typed the title here, I spelled it the same way I spelled it in the image above, which I posted to Instagram, and some people thought my misspelling was the point. Ha ha, oh yes, Of course, it was. (Oh, good heavens, why haven’t they invented spellcheck for handwriting yet. Why?? Why??) But I am going to keep the blog post title anyway, because maybe I know how to spell excruciating now. (I do! For the time being.) And because the above comment is pretty typical of what I come up with in my own revisions. Because you’re never going to get it perfect. Revising is all about showing your work, and about accepting that many parts of your literary house may not necessarily be sound, and then getting on with it anyway.

For me, learning to revise was such a revelation. Because I’d come up as a writer in blogging, you see, where getting to Publish was the point. Any blogger too focussed on revising is never going to be a blogger for long, and I’d argue that revising, or “polishing” blog posts is really procrastination, a way to avoid that terrifying moment when your piece goes live. A blog post is always a bit imperfect, somewhat raw, a work in progress—it’s intrinsic to the form. But a story or a novel is very different, and before you get to Publish, you’ll be revising it over and and over again.

I’m writing this post now, because someone emailed me last week having just completed the amazing First Draft milestone. (Huzzah! Crack open a bottle of wine!). And she knows, of course, that this finish line is only just the beginning of another marathon, and she wondered if I had any advice to share as she launches forth. And it happens that I do.

- Celebrate all the milestones. This is a bit of wisdom I learned from Sarah Henstra a few years ago, and it’s the truest thing in this whole endeavour. A story idea, 10 000 words, getting to THE END. Sometimes you’ve got to throw your own party.

- Take breaks. When the First Draft milestone is reached, put your story away for a few weeks. Do something new and difference. Change it up. You’ll come back to your project with fresh eyes and a more open mind.

- I like to read through my draft first without making changes, but just reading it to see what I notice, what it’s like to encounter the text from the outside. This is where I make general notes (like the poorly spelled one above) that provide me guidelines for when I really get down to work.

- Notice the good bits. The stand-out lines, the great scenes, the twist that works—I leave check marks scattered throughout the ms as encouragement to my future self and to remember that it’s not all bad.

- Set quantifiable goals. I find this easiest in first drafts (1000 words a day!) but with revisions, you can set page goals or time based goals. An hour or two a day of a social media-blocking app makes a very good clock.

- Change your font, or the spacing, or the layout of your document upon embarking on a revision. Changing the look of your manuscript will open your mind to more possibilities and untether your mind from the idea that your draft is fixed.

- Don’t be afraid to cut, even your favourite bits, the ones that don’t work, no matter how much you hope they will. I find it easier to create a new file to copy-and-paste these “scraps” to. In the end, I usually end up deleting the entire file and its contents, but a temporary storage space makes the process less painful.

- I love the metaphor of sculpting for writing, and I love the revision process because this time I don’t have to conjure my materials out of the air. Now I’ve got the clay, but it’s raw, and I’ve got to shape it. Or else I’m using a chisel to scrape the layers off and reveal the real shape that’s underneath. Alright, you can probably tell I don’t actually know how to sculpt anything. But my point: everything you need is there now, and this is the part where you get to dig deeper.

- Digging is different from polishing, Keep that in mind. Once again, polishing can be a procrastination—worrying about word order, or where to put your comma. These details are important, but you can worry about them later, and preoccupation with them can keep you from ever moving forward with the real work (which is DIG DIG DIG).

- My favourite scene in Mitzi Bytes is one that was written in a later draft, and the goodness of that scene, to me, underlines my faith in the revision process. There will be parts of your book that you’ll end up writing down the line that will feel like they were there all along just waiting for you to discover them.

- Revision is an opportunity to make your book the best that it can be. It helps to embrace this opportunity, and love it. It’s a process of discovering what your book is really about, and it’s kind of amazing and mysterious that you—its author—might not even know what that is yet. It’s actually helpful to never be too sure.

- If you’re lucky, you might have someone in your life who is willing to read your unedited manuscript (which is a big request to make of anybody). Make sure it’s someone who cares about you and your work, and someone whose opinion you respect. Remember that every time someone reads your work, it is an opportunity to practice the art of receiving feedback.

- And understand that the moment of realizing that your entire manuscript is garbage (which is also EXCRUCIATING) is a part of the process too. It’s always devastating to realize that your art that was perfect in theory in reality is never quite the flawless piece you imagined. But that’s what revising is for. Onward, and better and better all the time.

January 21, 2019

Bowlaway, Elizabeth McCracken

There is a house in Elizabeth McCracken’s new novel, Bowlaway, that defies all the rules of conventional architecture. It’s got eight sides and a cupola, a spiral staircase up the middle. “The walls were filled with lime and gravel and ground rice, and stuccoed with a combination of plaster and coal dust.” And in terms of narrative architecture, McCracken has similarly tossed out the rulebook for this, her sixth book and third novel. (Her two most recent books are the short story collection Thunderstruck and Other Stories, and a memoir, An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination.)

The unconventional house is not actually the novel’s central edifice, however, although they’re both commanded by the same character, a woman we meet in Bowlaway’s very first sentence: “They found a body in the Salford Cemetary, but aboveground and alive.” This is Bertha Truitt, of the gapped teeth and enormous bosom, who claims to be the inventor of candlepin bowling and is utterly uninterested in delineating the story of where she came from. (For the most part, so is Bowlaway itself.) Like everything McCracken writes—sentences, paragraphs, characters, action scenes—Bertha Truitt is vivid. The heart and soul of the book, one would think, or at least its foundation or supporting beam, if we’re back to architecture. But forget the rules, remember? Because Bertha Truitt is deceased by page 78 (and no, this is not “a spoiler.” Bowlaway is a book that could not be possibly be spoiled), swept away to her death in the Great Molasses Flood, Boston, 1919.

I will admit that at first I was unsure of my footing as a reader in this narrative, because it really is one in which the bottom can fall out at any time. Because I’d arrived at Bowlaway with fixed ideas about the way a narrative should go, ie the protagonist should not necessarily drown in molasses on page 78. Because this novel isn’t easy, and it’s full of tricks and play, and ghosts, and babies who die before they’re born, and sons who are actually ex-husbands. It’s not an simple read, and the reader has to pay attention, but the rewards of that attention are considerable, immense. Her previous novel, Niagara Falls All Over Again, which I loved, was about two vaudeville performers, and Bowlaway is similarly larger than life (McCracken is also author of a novel called The Giant’s House), a spectacle.

But instead of a stage, the setting is a bowling alley, Bertha Truitt’s candlepin alley, Truitt’s, later named Bowlaway two generations following (although the family tree is complicated). Scene of one spontaneous combustion, as well as a murder, and home to a ghost, McCracken follows the alley and its regulars through three-quarters of the twentieth century in a novel that is unlike any other book you’ve read before, as rare as an eight-sided house inhabited by extinct avian species. With sentences and imagery that are shocking in their freshness and perfection—the mother who gives out love in homeopathic doses, say. There is no other writer who writes like Elizabeth McCracken, and I’ve never read a book quite like Bowlaway.

January 18, 2019

The Back to the Blog Movement

“I blog to make sense of the world,” is the way that I’ve always explained my attraction to blogging, the way that I use my blog as a workbook, a scrapbook, part of a process toward understanding. But in the last couple of years, the world hasn’t made very much sense at all, and in ways great and small, I’d started to suppose that blogging was futile. Certainly people weren’t reading blogs anymore, and enticing readers to do so required wading into the mires of social media, where standards of behaviour were abysmally low and one gets the sense that with every scroll, the world becomes a place that’s slightly worse. But still I kept scrolling. “I’m not getting off twitter,” I’ve said on more than one occasion too late in the evening, scrolling, scrolling, “until the world becomes a place that I can understand again.” But it turns out the Twitter is even more futile than blogs are for sense-making, plus it’s passive, hijacked by capitalism, stupid algorithms, and rife with violence and abuse.

Last fall I experienced a distance from my blog, which I continued to update, but mostly with news and book reviews. I wrote fewer personal posts, though that was partly because Instagram really has taken over as my receptacle for quotidian things. I wrote less about my children, but that was more because they no longer exist in the world solely as extensions of my existence. I didn’t write many of what have always been by favourite posts, random explorations of connection-making, experiments in thought and narrative. I was always busy with paid work, and I was writing a novel, so much so that I didn’t worry so much about what was happening with my blog. But I was beginning to lose the habit of writing a blog, and the habit of thinking like a blogger, which is going out in the world with my eyes open to story and connections and questions. In losing some faith in the world, I’d also lost faith in those questions and connections’ ability to bring me closer to answers, which is a self-fulfilling prophecy when the end result is endless scrolling on Twitter.

The blog posts I was writing last fall didn’t always feel satisfying, didn’t seem to illuminate my understanding. I think I was feeling dispirited and and a little bit sad, writing posts about the crime of underfunding public education or about what it was like to have published a novel that was not a commercial success. By October, it had been a year since I’d last taught a blogging course or workshop, the longest break since I’d started teaching in 2011. “And really, I’d be happy never doing it again,” I remember saying, because I didn’t feel comfortable claiming to be a blog authority. Having forgotten, apparently, the cornerstone of blogging form, which is that having questions is far more important than having answers, and that no one is an authority ever.

But I did remember one thing I always told my blogging students, which is to write your way toward any answers you’re seeking. So a random post about a missing hat, or another about how I was looking for a babysitter. These were posts I wrote because it felt good to be writing and employing the first-person perspective again, though I wasn’t sure what they all added up to. In some ways, it felt like I was learning to be a blogger all over, learning to be uncomfortable. Questioning what this space was for, what stories I was telling, and what my voice was. So what’s the point? There usually wasn’t one.

Then in late December I spent a week and a half offline.

And when I returned to the internet in the new year, I realized there wasn’t much about the internet that I missed at all. I still liked Instagram, but that’s only because it is essentially a blog. Twitter brought me no pleasure. Facebook seemed like a waste of my time, and I would leave the site altogether…except for the people I like there. But then, if those people really want to hang out with me, can’t they come over to my blog? I’m really not hard to find—and suddenly the possibility this online space permits me seemed wide and exciting. I felt hopeful about life online for the first time in a long time, because I can conduct it on my own terms, in my own place. What if we stopped spending our time on websites owned by multi-million-dollar corporations that are demonstrably making the world worse all the time? What if the forty-five minutes I spent this evening having my brain turned to jelly trying to fathom the perspective of some guy on Twitter cheering on a right wing politician had been spent on anything else? What would life online be without the bots and the manufactured outrage, stupid algorithms, the trolls and the racist uncles? Totally meme-free, with unlimited characters, and nobody’s sharing any fake news article created by a shady network in Outer Siberia.

It would be a blog, of course. Right back where we started in Web 2.0, with stories and voices in a range that the world has never before been able to read, voices not in chorus, but not so polarized either. Connected, but not in a thread, more like a quilt, if we’re thinking in textiles. Niche onto niche, something for everyone. With room enough for stories, and questions, and nuance, and reflection, and changing your mind. And also for changing the world, in the small and subtle ways that blogs have always mattered—turns out I’m not ready to give up on that one just yet.

January 18, 2019

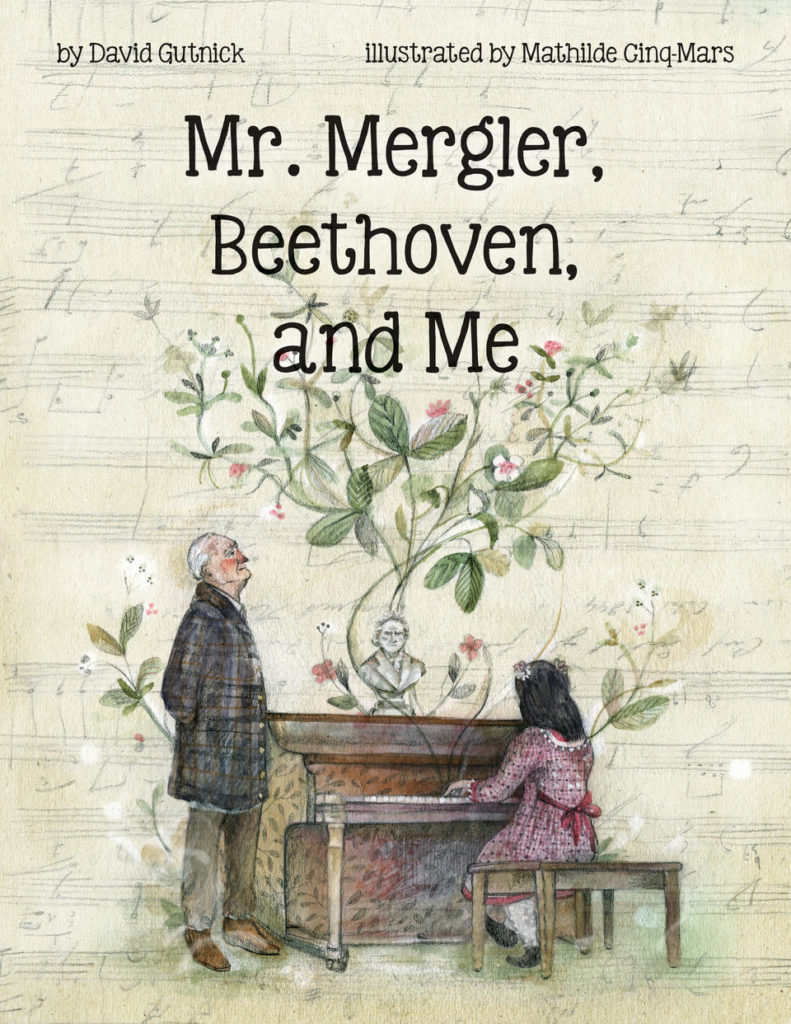

Mr. Mergler, Beethoven, and Me, by David Gutnick and Mathilde Cinq-Mars

My youngest daughter feels she is on intimate terms with Ludwig van Beethoven, because he’s rendered as a cartoon character in her piano book, and while she’s never heard any of his music properly, she’s played several simple songs inspired by his music, and when we picked up Mr. Mergler, Beethoven, and Me, by David Gutnick and Mathilde Cinq-Mars, she was very impressed and excited to learn that other people know about him too.

David Gutnick is best known for his CBC Radio Documentaries, and his first book for children is inspired by one he created about the legacy of Montreal music teacher Daniel Mergler. The book begins with a young girl who has recently arrived from China whose family meets and elderly man in the park, and as the girl’s father and the man talk together, it is shared that the young girl has a talent for music and that the elderly man, Mr. Mergler, has taught piano for many years. Mr. Mergler agrees to take on the girl as a student, and is not concerned that her family does not have money to pay for lessons: “Something tells me that she understands the magic that music can bring to her life. If she does, that is all the payment I need.”

She begins attended classes at Mr. Mergler’s warm and cluttered studio, evocatively rendered in Cinq-Mars’ illustrations. On top of his piano there is a bust of Beethoven, and he’s scowling. When the girl manages to play her songs with no mistakes, however, she begins to wonder: “Was it my imagination, or did [Beethoven] look a little more friendly?”

Now I have written before about my household’s intolerance for books about death, no matter how much I try to infuse our reading with my own morbid nature. They’re having none of it. And so what is so very excellent about Mr. Mergler, Beethoven, and Me is that the music teacher’s death is handled in a way that is neither corny nor devastating, although the girl certainly is sad, of course. But Gutnick shows how Mr. Mergler’s spirit lives on in the gifts he gave his students, in their passion for music. It’s the most delicate balance, but Gutnick achieves it perfectly.

January 17, 2019

This Keeps Happening, by H.B. Hogan

Don’t get too comfortable with the stories in H.B. Hogan’s debut, This Keeps Happening. Although even if you wanted to, you couldn’t, because you’ll only end up with eviscerated squirrels and a woman whose mother’s gross boyfriend has shit running down his legs, and where’s the comfort in that? But even still, it’s hard to look away, and each of these stories are really compelling, although the first couple conclude on notes that aren’t as illuminating as they’d like to be. By “A Fare for Francis,” about a cab driver in Thunder Bay whose fare doesn’t take his racist bait the wait he intends, however, I was locked in to this collection and read the entire thing on Sunday evening while soaking in the tub.

Hogan’s characters are shackled, all of them, whether by poverty and low expectations or else suburban lot lines, and if the alternative to the former is the latter, then one can see where the problems arise. In “The Babysitter,” a ten-year-old girl risks an encounter with a precocious teenage neighbour. In “The Princess is Dead,” a man despairs of his life while his wife sits in their house weeping over the death of Princess Diana. In “Empties,” a teenage girl longs for freedom and opportunity as she and her friend walk across Oshawa in an attempt to make six bucks returning bottles to The Beer Store. A conflict resolution class gets difficult in “Louis Remembers.” In “Esteem,” Alison’s middle-class dreams get trounced on and she ends up lying on the pavement. And then, “The Mouths of Babes,” which was so gross and horrifying that I had to tell my small children about it, and the darkness underlining, the mother stirring Kool-Aid, that reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye.

This is a book that grew on me, and a collection whose stories, characters and geographies I’ve been thinking about in the days since I read it. The opposite of being comfortable, this is a book that—in the best ways—gets under the skin.

January 16, 2019

Sparking Joy on the Radio

I got to talk about collecting books and keeping books and purging books on CBC Ontario Morning today! I come on at 34.30. Listen here.

January 16, 2019

This is Not a Metaphor

I understood it as a metaphor: it is okay to fall. It is okay to fall, to flail, to plummet. As much as can be expected from an ordinary human, I know this. I have lived it. Accepting, and even embracing, imperfection and failure has been key to any success I’ve managed to achieve along the way. But I have never managed to embrace this idea on a concrete level, concrete being the word, which is a hard and painful surface to have one’s body strike even at a moderate velocity. And it doesn’t even have to be concrete—for a few winters midway through my childhood, I used to go skiing, and I hated it, the terror. Where is the pleasure of sending one’s fragile physical self down a steep icy hill? I used to weave my way down slowly, slowly, repeated the mantra: Please don’t let me die. And then one day I occurred to me that I didn’t actually have to endure this anymore, so I didn’t. Why would I?

I took up ice skating four years ago with my daughter, who was five at the time. The task of teaching her to skate would fall to me, because it turned out I was the best skater in the family, even though I hadn’t skated in 25 years and never really enjoyed it as a child. Winter sports are not my thing. Sports in general even really aren’t, but at least in summer it’s not cold. I have memories of skating on canals when I was little, and these are mostly memories of freezing. And sore ankles. I mean, at least with skating you aren’t sending yourself down the edges of icy mountains, and the fall is never going to be so far. But still, there is falling. Even worse, there is fear of falling.

But for the last four years, I’ve been trying to commit to enjoying the winter outdoors, and skating has been part of that. It’s fun. Of course, I don’t enjoy skating as much as I enjoy having skated, which is my favourite part of the process, followed by hot chocolate. But I like it, and it’s free, and it’s been interesting to relearn an old trick, and to be learning alongside my daughter. I think it sets a good example for her too to see that acquiring new skills is not just the jurisdiction of children, and is important to keep doing this throughout one’s life. Her father and her sister have since joined in our skating life, all of us learning together. Harriet now gives me a run for my money as the best skater in the family, and last night Iris skated around the rink multiple times without holding onto my hand at all.

But we are slow. We are slow, and we skate in terror of those fast skaters who weave in and out among us slowpokes, or else the little kids who are skating haphazardly in the wrong direction and moving right into our path without consideration for the fact that none of us actually knows how to stop. None of us skate with ease, although my children have a bit more ease than I do because they’re more comfortable with falling. They’re closer to the ground anyway, and they’re fundamentally bouncy and less breakable, and with all the padding from their snowsuits they’re well protected. Neither of them likes falling, but it happens, and that’s okay.

I, however, have never fallen. Hardly something to brag about, because I’ve only never fallen because I’ve never being moving fast enough. From the metaphor, I know that the only people who never fall are people who’ve never been high enough to do so. As a skater, I am so cautious, nervous. I have been skating for four years with so much fear of falling—and then last night it finally happened.

I skated over a leaf, a dead leaf that had blown onto the ice, and I don’t know why it so destabilized me, but I felt it, the ground no longer steady beneath my feet. “It’s finally happening,” I realized, and there was so much time to think as it did. A brief attempt at re-finding my balance, but then then it was all over, and down I went. Landing with a spectacular crash on my bottom, which was better than my head taking the impact, or my wrists. “And it’s actually okay,” is what I was thinking as I lay there on my ice, except it wasn’t entirely because I’d knocked my littlest daughter over in the process (let’s not make a metaphor out of that, okay?) and she was screaming. Attracting the attention of the ice skating attendant, who came over to see if she was okay, and, “She’s fine, she’s fine,” I said, dismissing her pain. (But she was fine. Walk it off.) And then he helped me up, and I was almost euphoric, so much so that I forgot to even be humiliated.

Because the very worst thing had happened: I had fallen. And I hadn’t fractured my elbow or even sprained my wrist, or received a concussion. I didn’t break or shatter, which is what I’d always imagined. That I was fragile—but it turns out my body is stronger than I thought. And there really isn’t even a lesson beyond that—I’m still going to skate slowly, I’m not thirsting for opportunities to fall down again. It wasn’t like one of those Instagram memes where I thought I was falling, but it turned out to be flight, because it definitely wasn’t flight as I lay there on the Dufferin Grove Ice Rink staring up at the glow of the artificial lights. It was falling, but it was fine.

January 14, 2019

Ghost Wall, by Sarah Moss

I’ve been avoiding bookshops lately (except for a trip to Type Books’ new location in The Junction in December!) with a focus on reducing the overwhelming number of books on my to-be-read shelf. Which I’ve been pretty successful at with a huge tower of reading completed over the holidays, and also a clear-out of more than a few books that I decided to finally accept that I would never read. And when I finished reading Did You Ever Have a Family, by Bill Clegg, on Saturday morning (acquired from a Little Free Library; has been sitting on my shelf for months; is so incredible but also very sad) and we had no further plans for the day, I decided that what I really, really needed was a bookshop venture, and my family was kind enough to accompany me, obviously with the promise of snacks.

And what a wonderful thing, for me at least, although probably not my family, to arrive at the bookshop without an idea of what I was looking for. Something more uplifting than Did You Ever Have a Family, was my premise, though I wasn’t exactly successful on that front, but then a book need not be uplifting when it is brilliant, original and completely affecting. The book was Sarah Moss’s new novel, Ghost Wall, which only just came out (super exciting—I tend to be either six months or decades behind on all the newest things) and I’d read the review in the Toronto Star that morning. Beginning my Sarah Moss discovery, which I’ve been longing to embark upon on reading Rohan Maitzen’s reviews of her other books, which sound as intriguing as they are wide-ranging.

It’s a slim little novel whose design (in Canada, at least) is delicate and exquisite, a book made up of all kinds of competing tensions. Silvie is a teenager from Northern England whose bus driver father is an Iron Age enthusiast in his spare time, and she’s been raised on his rambles and fascinations of ancient Britons, and therefore knows how to forage for bilberries, which makes her an object of fascination for the university students her family is spending her dad’s annual leave with on their experiential archeology course. The professor and Silvie’s dad couple their skills and knowledge, leaving Silvie with the students, just a few years older than she is, worldly in a way she’s never been able to fathom. Her time with them is a brief reprieve from her father’s rigid control, but then she’s defensive around them, knowing they’re judging her parents’ accents and background. She also knows that aligning them too much will provoke her father’s wrath, whose force and dangerousness gradually becomes more apparent as the narrative progresses and underlines the novel’s idyllic setting and celebration of the natural world with something much more sinister.

Unabashedly feminist, Ghost Wall dares to question what people are really reaching for when they’re yearning for a simpler time, for an authentic kind of culture, or whiteness, or Britishness. Just what is fundamental about who we are and where we come from, and who gets to be in charge of that? It’s sharp, fast-paced, and disturbing, an exercise in minimalism and subtly. I loved it.