March 27, 2019

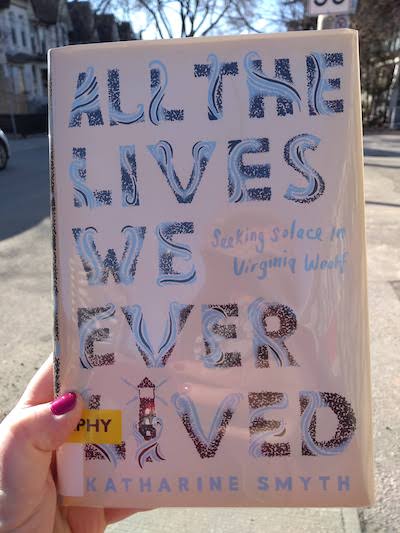

A To the Lighthouse Memoir

“…one of the wonders of Woolf’s novel is its seemingly endless capacity to meet you whenever you happen to be, as if, while you were off getting married and divorced, it had been quietly shifting its shape on the bookshelf” —Katharine Smyth

Lost somewhere in the flotsam and jetsam of Instagram is the post (from who? and when?) that prompted me to put Katharine Smyth’s memoir All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf on hold at the library. It might have been the cover that did it, a wonderful retro Hogarthian design, or maybe just the premise itself, a memoir via To the Lighthouse (and you either go in for such things or maybe you don’t—for the record, I was the target audience for Rebecca Mead’s My Life in Middlemarch Memoirs framed by reading experiences are so up my middlebrow street). To the Lighthouse is a book I’ve returned to again and again since I first read it in a university class 20 years ago—I was rereading it the summer I wrote my first novel, which is part of the reason why my protagonist ends up reading it for her book club. And the other part of the reason why To the Lighthouse turned up in my book is because of the uncanny way that it (like much of Woolf’s oeuvre) ends up seemingly connected to all things, wrapping its way around our own lives like tentacles. It is a book that one only appreciates more upon acquiring some life experience, and then some, a kaleidoscopic novel that contains multitudes: from Katharine Smyth, “To the Lighthouse tells the story of everything.”

I wonder if anyone who loves To the Lighthouse could write a memoir using the book as a framework—but they would probably not do nearly as good a job of it as Katharine Smyth has. Smyth, who studied at Oxford and took classes with Hermione Lee, who knows of what she writes, and whose prose does not read skimpily alongside Woolf’s own. Smyth is a writer with tremendous descriptive powers, a reveller of words and language—she sent me to the dictionary to look up “tenebrous.” And her own story is not a To the Lighthouse redux, but rather she tells the story of her father’s death—and also the story of her parents’ marriage, of her childhood, of her father’s alcoholism and years with cancer, of their waterfront home in Rhode Island—and it maps onto Woolf’s narrative enough to provide glimpses of illumination, just as Woolf’s own biography—her family’s home at St. Ives, the death of her mother, the devastation wrought by the Great War—illuminates her novel.

If it’s true that we tell stories in order to live, I think that we read them for the same reasons, to discover context, evidence, and meaning. After the death of her father, Smyth goes back to Woolf to better understand what happened to her family, to examine their complicated relationship, to bridge a gap between her memories of him and her life without him (ie [Time passes]). Hers would be an interesting story anyway, and she’s a wonderful writer, but it’s all the richer when regarded through Woolf’s literary lens and so is her reader’s connection to it.

March 25, 2019

A Book That Changed My Mind.

I am open to having my ideas challenged, which I think is also my silver-linings-seeking-self trying to cast in a positive light the fact that the universe has spent the last three years trouncing on my ideals and suppositions to the point where I not infrequently wake up on the night having heart palpitations and despair of humanity in a way I never did before (Luke Perry aside). I may have been wrong, but at least I’m learning, is what I mean, and I try to keep my mind and heart wide open and not succumb to fear, which only makes people stupid, by which I mean ignorant. Because even if I’m wrong, I want to be right (moral, just, thoughtful, etc.) but it’s still not very often that a book will come along and change my mind.

Although I don’t mean 180 degrees—but then this kind of binary this-or-that thinking is what got us into so much trouble in the first place. No, I mean “change my mind” as in a shift, a spark, a new kind of understanding. I’d never read a book by Naomi Klein before No is Not Enough: Resisting the New Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need, which was published in 2017 and I’ve basically been urging everybody I know to read it ever since I read it a couple of weeks ago (and then my best friend got confused and thought I was talking about Naomi Wolf and was worried I’d gone in for chemtrail conspiracies. I was happy to correct her—there’s nary a chemtrail in this entire volume).

I picked the book up because Megan Gail Coles (whose Small Game Hunting.. is such a brave and stellar novel) included it on her recommended reading list “Writing Through Risk,” books that “challenge literary expectations and community norms while demanding artistic honesty and human compassion.” In the book, Klein makes the assertion that the current US President and his chaotic administration are not as aberration, but instead “a logical extension of the worst, most dangerous trends of the past half-century.” Her thesis connects themes that have comprised her literary oeuvre—the hollowness of branding, economic inequality, and “shock doctrines”—to show how we got here from there, and also where we’re going.

And while I still don’t buy the argument that Tr*mp and Hillary Clinton are basically the same—as many people made during the 2016 election—I finally understand how he represents the very worst of the system that she is very much a part of and has profited from. I still think gender plays a larger role here than Klein discusses, especially when it comes to Bernie Sanders, who I think would have seemed less charismatic and impressive were he running against another man. Hating Hillary made it especially easy to love Bernie, I mean. And I mean too that Clinton’s attempts to work within the system would be held against her, even though the fact that she got as far as she did within that system as a woman is incredible and there were compromises she had to make in order to do so (and also comprises that men in her position [such as Secretary-of-State] make all the time and never are these figures so vilified).

But it’s the system, see, as Klein is hammering away at here, that is the problem. Hillary Clinton represents the futility of trying to change the system from within, a system that is rigged, flawed, gamed, and against the interests of most of us. If anything is ever going to be different—and it has to, because the earth is in peril—it’s the system that’s going to have to change.

Which is, of course, not the end of the story, but just the beginning, because how do we get there from here is the question now, but these shifts, I think, are the beginning of that. Asking questions about things we always took for granted, looking twice at parts of the status quo that make no sense at all (such as, who put Bill Gates and Bono in charge of everything?). This is such a smart, illuminating and worthwhile read, and ultimately even a hopeful one—although that might just be my silver-lining fixation showing again. And yes, you should totally read it.

March 25, 2019

Gleanings

- ‘Well, Miriam, it’s a good thing we’re Mennonites. At least you won’t get shot.’ ”

- Dealing with criticism

- White privilege is thinking you’re an oppressed minority because you can’t wear a racist symbol without being called a racist.

- Canada Reads and the gender gap.

- Antiracism is a process. Decolonial love is a process. Our love is a process. I never want it to end.

- It’s about figuring out how to be open and capacious and to let everything in and see what happens.

- Liking Books is Not a Personality [ed: this is bad news]

- Grace comes in many forms.

- Jansson is always an astonishment.

- My objection to private education is simply put. It is not fair.*

- I don’t travel with my fountain pen because it’s magic and I’m terrified of losing it.

- There’s something new and insidious about confessional-commercialism, which preys particularly on young women through the language of solidarity.*

- …how a life unfolds from what a pencil projects.

- The women who get me and get my taste are the women I follow on Instagram.*

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

*Credit for these items goes to Jessica Stanley, who publishes her own gleanings at Read.Look.Think.

March 22, 2019

It occurs to me that I’ve written a fantasy novel.

I’m finishing up a new draft of a novel I’ve written about a popular and charismatic politician whose career is derailed due to allegations of sexual misconduct a decade before. The novel’s central character is this man’s sometime-girlfriend, a young woman seventeen-years his junior who had been his employee—but something else has gone askew in their relationship (no spoilers) and they’re now estranged. What makes my novel interesting is ambiguity about the politician’s character, less so than what actually did or did not occur a decade ago. While the allegations against him may well be unfounded, smears in general upon his character are not exactly misplaced—he is indeed a forty year old man who a penchant for women born in the mid-1990s who happen to work for him. While none of that is illegal, it’s not a sign of impeccable character either. There is a small part of him that will concede that he has participated in an abuse of power—and (even if only in private) his mother would attest to that. She knows she’s let him get away with too much. It’s a good book, well plotted, nuanced. It’s been interesting to write the experiences of a 23-year-old woman who has no idea how much she still has to learn, who is refusing to be a victim. But it also occurs to me—thinking about Brett Kavanaugh’s face, and having read the memoir of the former leader of Ontario PC party whose own downfall inspired the premise of my story—that I have actually written a fantasy novel. A novel where a powerful man has a moment of contrition, for a moment questions his entitlement. “The defences of their choices would be vicious,” Megan Gail Coles writes in her incredible novel Small Game Hunting at the Local Coward Gun Club, which is the world we live in, instead of one where a mother might concede that her son could have hurt someone. I’m thinking of the incredible ending to Zoe Whittall’s The Best Kind of People, that devastating final sentence, that strict adherence to the status quo. When I read that book I didn’t really understanding how firmly committed are so many people to that narrative.

March 21, 2019

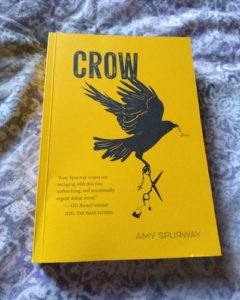

Crow, by Amy Spurway

It sounds like a book you might have read before—Stacey “Crow” Fortune leaves her flashy Toronto marketing job behind when she’s diagnosed with untreatable brain tumours and flies home to Cape Breton to face her fate, returning to the chaos of her mother’s trailer and grappling with the struggles of the community she thought she’d left behind. There is death, impoverishment, addiction, and long-buried family secrets—same old sad-sack CanLit, right? But wait. Because Crow, Amy Spurway’s debut novel, is a comedy, both larger than and bursting with life. Instead of a “bucket list”, Crow has a “fuck it list,” items she just can’t with anymore, which includes suffering fools or putting up with anybody’s bullshit. She’s calling it as she sees it, even if she isn’t always seeing it right, and she’s my favourite unabashed, fierce and brilliant heroine who has both a way with language and some neurological issues since Natasha Lyonne’s Nadia in the Netflix series Russian Doll.

Part of the joys of Russian Doll was its ensemble cast, and so too it is with Crow. Crow comes home to her two best friends, Allie and Char (who has also just returned home with her baby whose father is a Congolese diamond smuggler, and who is also deaf in one ear and says most words the way she’d always heard them: “F’eyed known there was a bomb fire, ida brung some bleeding’ marchmallows.” Plus there’s Crow’s mother, Effie, a long suffering housekeeper at the Greeting Gale Inn; Effie’s gossiping sister, Peggy; her old flame and pot dealer Willy the Gimp; plus Becky Chickenshit, Shirl Short, Bonnie Bigmouth, Duke the Puke, and the Spensers, Crow’s dead father’s family who ran the mines that kept the locals in employ (and sometimes killed them) for generations.

It’s a meandering plot, but then what journey towards death isn’t? And there were moments where I wondered if Spurway was really going to be able to pull this off, a comedy novel about serious business with a cast of hilarious misfits that could come close to bordering on caricature. The most incredible material but it requires authorial deftness to do it right—but Amy Spurway is the real thing. Her glorious sentences are something to behold in, from the very first few: “I come from a long line of lunatics and criminals. Crazies on one side of the family tree, crooks on the other, although the odd crazy has a touch of crook, and vice versa. I am the weary, bitter fruit—or perhaps the last nut—of this rotten old hybrid, with its twisted roots sunk deep in dysfunctional soil.”

The adjective “brave” gets thrown around all too often in regards to literature, but I’m going to pitch it here, because it’s right for a variety of reasons. First of all, a book about death—and mental illness, and disability, and abortion, and spousal abuse, and class, and poverty—and the narrative takes no shortcuts or shies away from the hard stuff. I kept waiting for the part where it veered off course or fell into the saccharine, but that point never happened. Crow delighted me and amazed me the further I read, with its freshness, its daring, its refusal to conform (and the projectile vomiting). The bulbs that Crow finds in her mother’s trailer, and what comes up in the spring—it’s all just perfect (but no spoilers). And oh my gosh, the ending—it was literally stunning. The narrative entire is a veritable tightrope walk, a feat that’s performed with style and verve, and it’s absolutely dazzling.

“And then there’s the bigger, more grandiose questions about will happen when I’m gone,” Crow considers. “Where am I going? Anywhere? Nowhere? Somewhere? Somewhere good? Will there be tea and squares and laughing and crying and swearing there, because if there isn’t, well then I don’t want to go.” And you really can’t blame her. After 300 pages in this incredible novel, I wasn’t ready to be finished either.

March 20, 2019

Books on the Radio

I was talking books on CBC Ontario Morning today and am really excited about my choices. You can listen again here—I come on at 42.00.

March 19, 2019

Notes Towards Recovery, by Louise Ells

There is a sense of the foreboding in the first story of Louise Ells’ debut collection Notes Towards Recovery, a story called “Erratics.” “I wonder what’s left,” the narrator wonders, considering the place in Ontario’s Muskoka region where her family had spent their summers during her childhood. “Later, I’d read about the Lindbergh case in one of the Reader’s Digests that lined the bookshelves of every privy on the Lake,” she explains, and she fears for her younger brother from the time he is a baby, as he grows up five years younger than she is, and the story keeps returning to the big rock the children jump from into the lake. Is someone going to get hurt? But what happens turns out to be something the narrator never even thinks to anticipate, and this is a point underlying the stories in this collection, how different fate is from the stories we’re told about who we’re supposed to be, and how far what really happened is from the memories we carry.

Before I read these stories, I was first intrigued by Louise Ells’ biography—working as a chef, a roofer, co-pilot on a submarine, and she would eventually write her doctoral dissertation on the works of Alice Munro. And Munro’s influence shows in these stories, which are very much Ontario stories, most of them set outside of Ottawa in Renfrew County. They are concerned with memory, with history, and are wary of nostalgia. Even in those golden long-ago summers, husbands were cheating, mental illness was ignored, pregnant girls were sent to an aunts, and same-sex relationships were considered deviant. And the protagonists of Ells’ stories are left to grapple with those history, which they struggle to let go of, even with the trauma. Trying to make their way forward into the future: the story “Mirrored” begins: “I thought I’d manage without a map.” Spoiler: It’s not so simple.

I liked these stories a lot, although the collection itself might have benefited from some pruning—the stories near the beginning of the book were stronger than those towards the end, although it might also have been that there are twenty-one stories in the collection with recurring themes and ideas, and they’d lost their freshness as I got to the final third and started to blend together. Or possibly this is a story collection that’s not best read straight through, one story after another. But that is how I read it, not least because most of these stories themselves were strong and compelling. Notes Towards Recovery is a remarkable debut.

March 18, 2019

Gleanings

- It’s why I love swimming. When I’m swimming, swimming is the only thing I can do.

- What if writing helps you understand the world and the people in it today just a little better than you did yesterday?

- I think I kind of love uncertainty, if I’m being honest.

- Collectively, we have a role to play against the spread of hate.

- Maybe what we need is not more explorations of how meaningless everything is, but a radical reassertion of that meaning, the kind of hope that kept Woolf alive.

- Ardern’s leadership not only impressed the world, but also sadly reminded us what’s missing in most leaders.

- “We’ve got a pact,” Ziegler said. “You have permission to read for an hour, with no other interruptions.”

- On unknowingly reading a Christian novel.

- …a lot of stuff has been written at my kitchen table. I’ve daydreamed there. I’ve been happy in my kitchen.

- I find it moving to imagine Welty reading To the Lighthouse when Woolf was still alive, just as Welty was alive when I first found that story.

- That’s precisely the way a “grab”-heavy text reads to me after a while.

- I have to admit that every time I seal up a letter or finish a postcard, I stand back and admire it with a feeling of warmth and accomplishment.

- Thanks mostly to all my farmer friends who have ever so patiently(?) educated me, I have a grander appreciation for winter.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

March 15, 2019

Moon Wishes, by Patricia Storms, Guy Storms, and Milan Pavlovic

It was no contest what book I was going to write about for #PictureBookFriday this week, which has been the week of our March Break staycation, a marvellous week of travelling around town and taking in the best of what Toronto has to offer, which has included the Ai Weiwei exhibit at the Gardiner Museum, the library, a family swim, a return visit to Winter Stations at Woodbine beach, St. Lawrence Market and the Old Spaghetti Factory, and then yesterday, which was everybody’s highlight: a trip to see The Moon: A Voyage Through Time at the Aga Khan Museum, which was extraordinarily rich, and wondrous, and fascinating.

And which gave us a deeper appreciation for Moon Wishes, a new picture book from author/illustrator Patricia Storms, and one that is is written along with her husband, Guy Storms, and illustrated by Milan Pavlovic. And what a treasure this team has produced, a gorgeous story with images just as beautiful, a story about what the moon shines on, which just happens to be everything. (One of my favourite parts of the moon exhibit was the artist’s statement by Luke Jerram, who created the illuminated moon replica, who described the moon as “a cultural mirror.”)

“If I were the moon, I would paint ripples of light on wet canvas,” the book begins, and we see a school of fish swimming in the moon’s reflection. We see the moon shining over a group of migrants, all their belongings on their backs: “I would wax and wane over the Earth’s troubles…wishing peaceful sleep for worried hearts.” The moon is a constant, lighting up the darkness, always changing, just like everything is. “I would be a beacon for the lost and lonely…lighting the way home” And shining on all the creatures everywhere, in the sea, and on the land, in the woodlands, and on the coasts. Connecting all of us, both big and small.

March 14, 2019

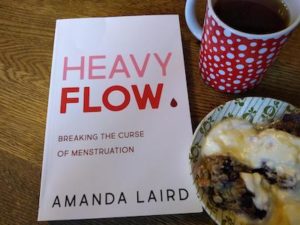

Heavy Flow, by Amanda Laird

I may read a lot, but it’s never a challenge to name one single title in answer to the proverbial demand, “Name a book that changed your life.” Always, it’s Taking Charge of Your Fertility, by Toni Weschler, which I read ten years ago, shortly before becoming pregnant with my first child. And while I’d had a fairly good idea of how to get pregnant before reading the book, and had even been pregnant once before but completely by accident, there was so much more I didn’t know than what I did about the things my body had been doing for years, things I’d never paid any mind to. I learned things about vaginal mucus that blew my mind, and I’ve never looked back. But I’ve also not thought about it all much deeply a whole lot since, especially since I finished having children. My menstrual cycle, I’ve been thinking, is now pretty much redundant—but then it turns out that fertility is only the tip of the menstrual iceberg. (And there’s an image to keep in mind.)

And then along comes Amanda Laird to inform me of what I’ve been missing, first with her Heavy Flow period podcast (which I’ve become devoted to) and now her new book, Heavy Flow: Breaking the Curse of Menstruation. A book that shatters the myth that fertility is what the menstrual cycle is all about. Laird comes as menstruation from the perspective of a holistic nutritionist (albeit one who was making period-positive zines two decades ago and dabbled as an amateur gynaecologist aka the friend you come to with all your weird period questions), and situates the menstrual cycle in the broader perspective of general health. Because your menstrual cycle (which is about more than just those five to seven days in which you’re bleeding) also impacts bone density, breast health, heart health, and your nervous system. Because your menstrual cycle can be a key indicator of other health problems if symptoms go awry—and if symptoms are always awry (for example, painful periods, which too many doctors dismiss as “normal) it often does mean that something is wrong. Although it’s hard to address those concerns, because of menstrual taboos—even in this period positive age in which access to menstrual products is beginning to be a major topic of political discussion, too many people are still expected to put up with and shut about period pain, and remain in the dark about how and why their bodies do what they do.

(I especially love Laird’s pragmatic view on health, and politics, and everything. In everything she does, she resists binaries, and complicates matters in really intelligent ways, which is altogether rare and refreshing.)

Heavy Flow has been a revelation to me, just as Taking Charge of Your Fertility was a decade ago. I’ve learned why my menstrual cycle is still worth paying attention to (and from the podcast, I’ve been more enlightened about peri-menopause and menopause than many other menstruators get to be), how to advocate for myself to medical professionals, and how things like nutrition and lifestyle can impact hormonal health. I also learned how the fallopian tube got its name—which was the first point in reading this book at which I exclaimed. “Oh my god!” in consternation with the patriarchy but it was not the last.