April 5, 2019

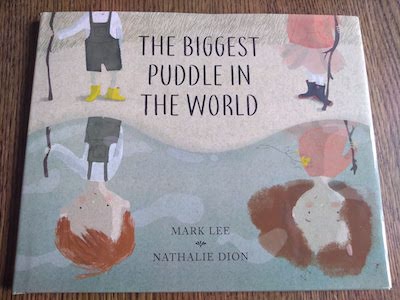

The Biggest Puddle in the World, by Mark Lee and Nathalie Dion

I’ve been meditating a lot on connection lately, how one thing leads to another, the ways that small things can cumulate in big things—which is the underlying message of The Biggest Puddle in the World, by Mark Lee and Nathalie Dion. But it’s a message that’s buried deep inside a wonderful old-fashioned story about two siblings who go to stay with their grandparents (Granny B. and Big T) for six whole days while their parents are away. In beautiful illustrations rich with gorgeous mismatched prints (damask wallpaper, floral duvet, mattress stripes to die for) we’re shown the siblings exploring their grandparents house as the weather outside just rains and rains and pretty soon the two are out of playtime options. But then: “The next morning patches of sunlight appeared on the kitchen floor.”

And so they head outside wth Big T. with a challenge: a search for “the biggest puddle in the world.” “The wet earth and the shiny grass smelled like spring. During the rain, a clump of mushrooms had popped up on a log.” They find one puddle, and then more puddles, but none of them constitute “the biggest puddle in the world.” Their grandfather encourages them, “Follow the water,” and they do, as the trickles from puddles turn into a stream, and then a pond. And they take a break from searching to create a puddle map, and then learn how puddles turn into clouds, which are made from bodies of waters everywhere, including that still-elusive big puddle that they’re looking for. Which they find by following a river through thorn bushes and down a muddle hill to reach a beach, and there it was: the ocean. The biggest puddle in the world!

The prose is lovely to read and the illustrations soft, dreamy and detailed, as absorbing as the story is. Just the book for April, and all its showers—it’s a perfect springtime read.

April 4, 2019

A Mind Spread Out on the Ground, by Alicia Elliott

One of the first essay collections I ever fell in love with back when I was first falling in love with the essay was Pathologies, by Susan Olding, who was later kind enough to write a short piece at 49thShelf about the essay form. Olding wrote, “In an unstable world, we want to know what we’re getting, and with an essay, we can never be sure. Partaking of the story, the poem, and the philosophical investigation in equal measure, the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go. Places we may not want to go. We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave. That’s the risk we take when we pick up an essay.”

It might be the risk, but it’s also the reason, as demonstrated by Alicia Elliott’s remarkable and now-bestselling debut, A Mind Spread Out On The Ground. A collection of essays that examine stories and ideas from all angles, not one side, or even (more importantly in this age of polarization) both sides, but instead acknowledge a myriad of viewpoints, or points of consideration. These are essays that resist certainty, neat conclusions, simple morals. Instead: there is multiplicity, complication, tension, and this is what makes the book so fascinating. “Sontag, in Snapshots” begins with self image and photography; and then photography and colonialism; Black Lives Matter and video recordings of police brutality; on photography and agency, and also community; cultural stigma of “selfies” and misogyny, and imperial beauty standards; and photography as “a family building exercise;” then landscape photography in Banff vs. the Kinder Morgan pipeline and how some mountains are more worthy than others; and torture a Abu Ghraib; revenge porn; and what it means to have one’s pain witnessed, corroborated. It’s an essay that ends with questions instead of answers, ever expansive, “Why do we need our lives to be witnessed? Why do we need to share our experiences, to have this connection to others? Why do we need to control others so badly and so completely that we will even try to control their image? Is it because we’re trying to make ourselves more real? Is it because that power—as expansive or minuscule as it may be—fills a void?”

As Olding writes, “the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go.”

While Elliott’s essays—which portray her experiences growing up in poverty, as an Indigenous woman, as the child of a mother with mental illness, a teenage mother herself, a survivor sexual assault—recall (in the best way) the groundbreaking work of Roxane Gay in her collection Hunger—a collection that also lays bare the experience of trauma—they are also different in tone. While rawness is a feature of Gay’s essays in her collection, Elliott’s are more processed, polished, synthesized in a way I hadn’t entirely been expecting from someone who (admittedly, in addition to winning magazine awards, being awarded the RBC Taylor Emerging Writer Prize, being nominated for the Journey Prize, and appearing in Best American Stories, so we should have seen it coming) has made a name for herself with incisive Twitter threads and having none of your racist bullshit on that particular social media platform.

But with her first book—which is eminently readable, absorbing and hard to put down—Elliott solidifies her reputation as a profound thinker and prose stylist, in addition to being a Twitter powerhouse. Perhaps the tweets are where her rawness is, but readers of her essays will find a voice more cool and discerning, and oh-so-fucking smart. Good luck trying to mess with “Not Your Noble Savage,” a consideration of literary colonialism that is coming at you with receipts (as they say on the Twitter), with Margaret Atwood in an essay claiming that Pauline Johnson (as an Indigenous writer) is not “the real thing,” but Thomas King (“the son of a Cherokee father and a Swiss, German and Greek, ie white, mother”) gets to be. “[L]et’s consider Canada’s history of dictating Native identity,” proposes Elliott, and then this leads to considerations of how Indigenous writers’ work is “policed” by critics, and the charade of reconciliation, and “the fairy tale that keeps Canada’s conscience clear.”

Recalling Olding’s, “We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave.”

Oh, the places where these essays take us. She writes about learning the verdict in the Gerald Stanley case, on trial for the killing of Colten Boushie, while visiting the space centre in Vancouver while on vacation with her family, “dark matter” as a metaphor for racism—”it forms the skeleton of our world, yet remains ultimately invisible, undetectable.” I haven’t had lice since February (knock on wood) so was able to read her essay “Scratch” without too much creepy-crawly imaginings. She writes about mental illness, and the Mohawk phrase which describes it, which is where Elliott’s collection gets its name. About being Indigenous while looking white, and her ambivalence about her child receiving the same inheritance; on cultural appropriation and what it meant when she read Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s Islands of Decolonial Love, the first time she’d read the work of another Indigenous woman—she writes, “Every sentence felt like a fingertip strumming a neglected chord in my life, creating the most gorgeous music I’d ever heard.”

I’ve not even touched on her essay about Toronto’s Bloor and Lansdowne neighbourhood, about gentrification; the one about nutrition, poverty and its colonial legacy; about her marriage (“Antiracism is a process. Decolonial love is a process. Our love is a process…”) About attempting to understand and love her complicated and troubled mother. Her essay, “Extraction Mentalities,” which is a “participatory essay,” something I’ve never encountered before, with literal space on the page for the reader to engage with her questions. And throughout the entire book, really, Elliott has created space to engage with her questions, the entire project infused with this characteristic generosity. To be at once fierce and powerful, but also vulnerable and tender—what a gift that is to her reader. And what a gift this whole book is, strumming a neglected chord that the world needs to hear right now.

April 3, 2019

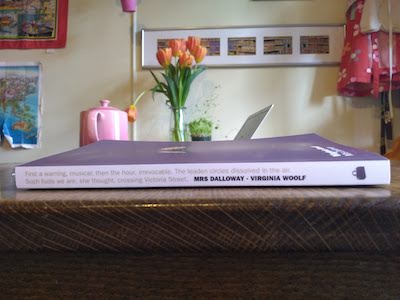

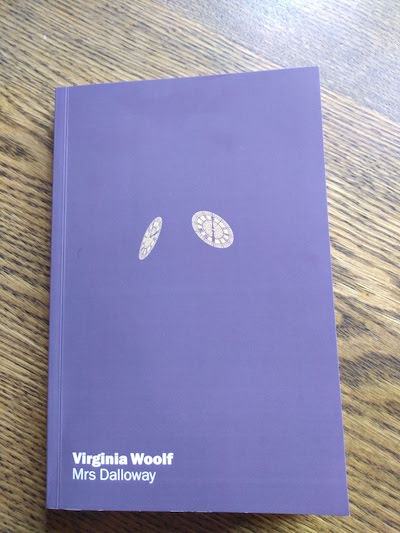

Mrs. Dalloway: Redesigned

I like to read in a stream of literary consciousness, unplanned, meandering, one book leading to another in an organic fashion that I need not think about too deeply, but it just makes sense. My logical mind is not in charge of it, though things like library due dates factor in, and also whether or not a hardcover will fit into a particular handbag, or just how appropriate a book might be for the beach. But for the most part, I let the books decide, like how I was finishing up All the Lives We Ever Lived last week, and then Mrs. Dalloway turned up in my mailbox.

Mrs. Dalloway is the latest release from Ingrid Paulson’s Gladstone Press, which also published The Age of Innocence, a book I read over Christmas and turned me into a full-fledged Gladstone Press enthusiast. And when I heard that Mrs. Dalloway would be the first of their 2019 releases, I was ecstatic, because I love this book. a book I’ve returned to several times since I first learned to read Virginia Woolf (for me, it was not instinctual) twenty years ago when I was an undergraduate. It’s funny, because while I like to read in a stream of literary consciousness, the act of actually reading stream-of-consciousness is not my ideal. Because it’s hard and you have to pay attention and nothing’s fastened you to the plot so you have to do all that work yourself.

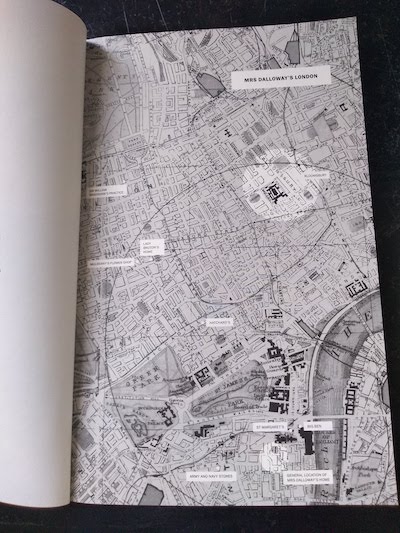

But I can do it with Woolf, with Mrs. Dalloway. Not getting too caught up in the details, letting the atoms fall where they may. It takes practice, and confidence, and patience, but I find it so rewarding. And easier too in a book that’s brand-spanking new, with a map even (my second-hand Penguin paperback that had once belonged to someone called S. Hull, according to the title page, didn’t have that) so I could follow Mrs. Dalloway, and Septimus Smith, and Peter Walsh through the streets of London, through the hours of day in June, right up to the party. For which Mrs. Dalloway had bought the flowers herself.

Gladstone Press books are available for purchase via their website, and are also currently for sale at Type Books on Queen Street West in Toronto. And as for me, my walk with Mrs. Dalloway led next into a walk with Alicia Elliott in her extraordinary and now bestselling essay collection A Mind Spread Out On the Ground, and then to Anna Burns’ award-winning Milkman, which is another walking book. And I’ll keep you posted as to where my literary journeys take me next.

April 2, 2019

A Deadly Divide, by Ausma Zehanat Khan

It was uncanny to be reading Ausma Zehanat Khan’s latest mystery A Deadly Divide, a novel about a (fictional) mass shooting at a mosque in Quebec. For obvious reasons, of course, after the terrorist attack in Christchurch, but also because of the voices that are a part of Khan’s narrative in this novel, her fifth one about Detectives Esa Khattak and Rachel Getty, who work as part of a “Community Policing” team investigating crimes involving immigrant communities. (In her previous novel, A Dangerous Crossing, the detectives end up on a Greek island investigating a case involving trafficking Syrian migrants; the first book in the series, The Unquiet Dead, was about the 1995 Srebrenica massacre; Khan holds a Ph.D. in international human rights law).

“I wrote this book because I have long studied the incipient and incremental nature of hate and the fatal places hate often takes us,” Khan explains in her Author’s Note. “I wrote it to illuminate the connections between rhetoric, polemics, and action. To suggest that the nature of our speech should be as thoughtful, as peaceable, and as well-informed as our actions.” The novel includes online conversations between users on a white supremacy chatroom, conversations which one might call “vividly imagined” on Khan’s part in how entirely lacking they are in imagination—or empathy, or understanding. The lines being blurred between fiction and reality as I was reading this book, as I was reading comments from the Yellow Vest Movement’s Facebook pages. The dangerous rhetoric out there, and it’s terrifying, Khan connecting the dots between the things people post and write, all the supposedly harmless provocateurs—her novel features a radio DJ who relishes pushing boundaries and buttons—, the oh-so principled free speechers for whom the right to say anything at all trumps the right for other people to be unthreatened in the places where they live.

Esa and Rachel arrive in Gatineau in the aftermath of the mosque shooting, where a Priest who was found holding a gun at the scene has been released, and a Black paramedic who was praying at the mosque and went back inside after the shooting to help his friends has been arrested. Meanwhile Esa and Rachel an old friend, a student at the local university and a civil rights activist whose work has been catching the attention of a white supremacy organization on campus. And the activist’s ties to the leader of that organization are complicated, and so are Esa and Rachel’s relationship with the head of the police team they’re working with in Quebec. Who is to be trusted? Khan doing her best job yet in the series, I think, of plotting out twists and turns and always keeping her reader guessing—so that this book, which is a social treatise, turns out to also be a riveting detective novel at the very same time.

April 1, 2019

The Narrative Value of Abortion

I am still not finished writing about abortion (or talking about abortion), not least because writing about abortion/ de-stigmatizing abortion / acknowledging abortion as ordinary is more important than it’s ever been with women’s reproductive rights and access to abortion under threat in a way I never anticipated they would be when I had my own abortion 600 years ago and even had the nerve to take my access to abortion for granted—how very 2002/”post-feminist” of me, right?

And there, I just used “abortion” eight times in a sentence, which I think was the general guideline put forth by Strunk and White in their Elements of Style. Something along the lines of, “Write abortion eight times in a sentence, then go do seven impossible things before breakfast.” (For six and under, you’re pretty much on your own.)

I keep writing about abortion because people with no experience of abortion keep trying to make laws about abortion, and the tyranny and injustice of that terrifies me. But I also keep writing about abortion, in fiction in particular, because it’s really interesting from a narrative point of view. As Lindy West writes in Shrill, ‘My abortion wasn’t intrinsically significant, but it was my first big grown-up decision—the first time I asserted unequivocally, “I know the life that I want and this isn’t it”; the moment I stopped being a passenger in my own body and grabbed the rudder.”’ And from a character-development standpoint, such a moment is pure gold for an author, along with the nuance and ambiguity that comes with the experience of abortion. The defiance, the agency, the courage—these qualities are what character is made of. And the variable ways an abortion is experienced by a couple too, if the pregnant person finds herself in that kind of arrangement. How it could bring two people together, or push them apart, or make clear a reality that’s been present all along.

The possibilities are endless, as to what can happen to a woman (fictional or otherwise) who has an abortion, and endless possibilities are kind of the whole point of abortion anyway. And not that all those possibilities are free and easy—what choice in any life ever comes with such certainty? But it’s about plot and richness and tension and balance, and knowing that a single thing can have two (or more) realities, that a reality can be true and not true at once, which is the entire jurisdiction of fiction.

So I am not finished putting abortion in my work, because of the fact of abortion in the world, regardless of whether or not it makes you uncomfortable. And maybe in this instance, your comfort is not the point? Instead, for the reader, finding abortion in our fiction brings home the ordinariness of abortion in the places where we live—our homes, our families, our small towns and big cities. Writing about abortion is not a question of changing the world, but instead of catching up with it, acknowledging the reality what life has been like all along.

April 1, 2019

Gleanings

- I am rereading Emily of New Moon because of Russian Doll.

- It only took 50 very nice, polite people, including several kids, to…disrupt his agenda.

- To rescue even one child with learning problems or special needs from humiliation in the classroom and at home and from lifelong feelings of low self-esteem, is exhilarating.

- Consider how different our public policy outcomes would be if lobbyists, government-relations professionals, and former political staffers did not dominate the newspaper columns or the evening punditry panels.

- I was opening a tin of mushroom soup for lunch today when this warm wave of recollection washed over me.

- A woman’s wisdom comes, in part, from the great juggle of her life.

- I lose the thread, I miss the connection, I falter, I am lost. What just happened?

- When I wake in the night, I have the sense that everything I know is connected, that I need to find way to stitch it all together like a useful and beautiful length of tapestry.

- But sometimes, I just need them to be game. Sometimes, I just need it to to be easy.

- and the best unexpected gift of all this is how the organization of it makes me feel like I suddenly live in my very own bookshop…

- I feel like this book is so tightly bound to the bookstore, and to your understanding that readers needed a book about a life crisis that didn’t result in hiking the Pacific Crest Trail.

- Paradox: How to be proud of and show off one’s work without being offensive. Not an easy task, not by a long shot!

- Being funny is, in a number of key respects, incompatible with conventional femininity.

- I’ve given up that mythical “trying to strike a balance in life” thing, and now I really just strive to not be shattered into a million pieces.

March 29, 2019

Nature All Around: Trees, by Pamela Hickman and Carolyn Gavin

My nine year old daughter Harriet knows everything, and she continually surprises me. Because who was it that taught her about constellations, garden slugs, axolotls, or the life cycle of a piraña? It wasn’t me, who still sometimes gets tulips and daffodils mixed up, and didn’t actually know what an iris looked like until after I’d given that name to a human. But it’s not altogether a mystery, where Harriet gets her knowledge from, because she’s an avid reader of nonfiction, devouring the “Do you know…” series from Fitzhenry and Whiteside, and Elise Gravel’s “Disgusting Critters” books. Every time we go to the library, she picks up another books about animals or plants—for a while she was really into fungi. (She also really likes Jess Keating’s books, her nonfiction and her novels alike.) But I have to confess that with some rare exceptions, children’s nonfiction books don’t really do it for me.

But then along comes Nature All Around: Trees, by Pamela Hickman and illustrated by Carolyn Gavin, a book that has been given a permanent home on our coffee table. Because it’s gorgeous, just the thing for those of us who are wild about botanical paintings, and a sensibility not dissimilar to Leanne Shapton’s beautiful Native Trees of Canada (with a sprinkling of Carson Ellis and Esme Shapiro).

I love this book! It’s beautiful just to leaf through (ha ha) with its paintings of leaves in their glorious variety, and filled with fascinating tree facts, the difference between a simple leaf and a compound leaf, explanations of photosynthesis, pollination, and features on “strange trees” like the 23-story tall sequoia that’s probably 2000 years old, or the larch tree, which is special because it’s coniferous and deciduous at once.

The terrible thing is that because I am not nine, my mind is a sieve, and I can never remember anything, which is a good excuse to keep this book on the coffee table—in addition to its pleasing aesthetics—because then I get to read it over and over again.

PS Another tree book I’m super looking forward to this spring is Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests, by the amazing Ariel Gordon.

March 27, 2019

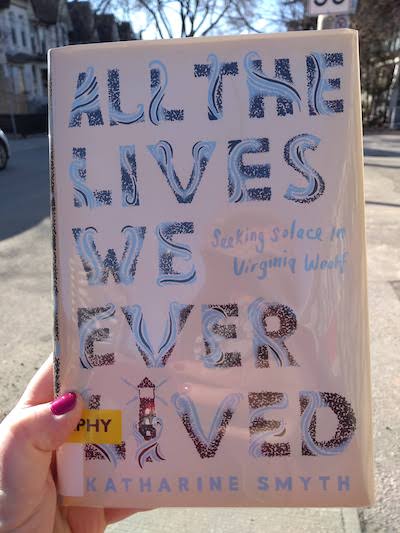

A To the Lighthouse Memoir

“…one of the wonders of Woolf’s novel is its seemingly endless capacity to meet you whenever you happen to be, as if, while you were off getting married and divorced, it had been quietly shifting its shape on the bookshelf” —Katharine Smyth

Lost somewhere in the flotsam and jetsam of Instagram is the post (from who? and when?) that prompted me to put Katharine Smyth’s memoir All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf on hold at the library. It might have been the cover that did it, a wonderful retro Hogarthian design, or maybe just the premise itself, a memoir via To the Lighthouse (and you either go in for such things or maybe you don’t—for the record, I was the target audience for Rebecca Mead’s My Life in Middlemarch Memoirs framed by reading experiences are so up my middlebrow street). To the Lighthouse is a book I’ve returned to again and again since I first read it in a university class 20 years ago—I was rereading it the summer I wrote my first novel, which is part of the reason why my protagonist ends up reading it for her book club. And the other part of the reason why To the Lighthouse turned up in my book is because of the uncanny way that it (like much of Woolf’s oeuvre) ends up seemingly connected to all things, wrapping its way around our own lives like tentacles. It is a book that one only appreciates more upon acquiring some life experience, and then some, a kaleidoscopic novel that contains multitudes: from Katharine Smyth, “To the Lighthouse tells the story of everything.”

I wonder if anyone who loves To the Lighthouse could write a memoir using the book as a framework—but they would probably not do nearly as good a job of it as Katharine Smyth has. Smyth, who studied at Oxford and took classes with Hermione Lee, who knows of what she writes, and whose prose does not read skimpily alongside Woolf’s own. Smyth is a writer with tremendous descriptive powers, a reveller of words and language—she sent me to the dictionary to look up “tenebrous.” And her own story is not a To the Lighthouse redux, but rather she tells the story of her father’s death—and also the story of her parents’ marriage, of her childhood, of her father’s alcoholism and years with cancer, of their waterfront home in Rhode Island—and it maps onto Woolf’s narrative enough to provide glimpses of illumination, just as Woolf’s own biography—her family’s home at St. Ives, the death of her mother, the devastation wrought by the Great War—illuminates her novel.

If it’s true that we tell stories in order to live, I think that we read them for the same reasons, to discover context, evidence, and meaning. After the death of her father, Smyth goes back to Woolf to better understand what happened to her family, to examine their complicated relationship, to bridge a gap between her memories of him and her life without him (ie [Time passes]). Hers would be an interesting story anyway, and she’s a wonderful writer, but it’s all the richer when regarded through Woolf’s literary lens and so is her reader’s connection to it.

March 25, 2019

A Book That Changed My Mind.

I am open to having my ideas challenged, which I think is also my silver-linings-seeking-self trying to cast in a positive light the fact that the universe has spent the last three years trouncing on my ideals and suppositions to the point where I not infrequently wake up on the night having heart palpitations and despair of humanity in a way I never did before (Luke Perry aside). I may have been wrong, but at least I’m learning, is what I mean, and I try to keep my mind and heart wide open and not succumb to fear, which only makes people stupid, by which I mean ignorant. Because even if I’m wrong, I want to be right (moral, just, thoughtful, etc.) but it’s still not very often that a book will come along and change my mind.

Although I don’t mean 180 degrees—but then this kind of binary this-or-that thinking is what got us into so much trouble in the first place. No, I mean “change my mind” as in a shift, a spark, a new kind of understanding. I’d never read a book by Naomi Klein before No is Not Enough: Resisting the New Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need, which was published in 2017 and I’ve basically been urging everybody I know to read it ever since I read it a couple of weeks ago (and then my best friend got confused and thought I was talking about Naomi Wolf and was worried I’d gone in for chemtrail conspiracies. I was happy to correct her—there’s nary a chemtrail in this entire volume).

I picked the book up because Megan Gail Coles (whose Small Game Hunting.. is such a brave and stellar novel) included it on her recommended reading list “Writing Through Risk,” books that “challenge literary expectations and community norms while demanding artistic honesty and human compassion.” In the book, Klein makes the assertion that the current US President and his chaotic administration are not as aberration, but instead “a logical extension of the worst, most dangerous trends of the past half-century.” Her thesis connects themes that have comprised her literary oeuvre—the hollowness of branding, economic inequality, and “shock doctrines”—to show how we got here from there, and also where we’re going.

And while I still don’t buy the argument that Tr*mp and Hillary Clinton are basically the same—as many people made during the 2016 election—I finally understand how he represents the very worst of the system that she is very much a part of and has profited from. I still think gender plays a larger role here than Klein discusses, especially when it comes to Bernie Sanders, who I think would have seemed less charismatic and impressive were he running against another man. Hating Hillary made it especially easy to love Bernie, I mean. And I mean too that Clinton’s attempts to work within the system would be held against her, even though the fact that she got as far as she did within that system as a woman is incredible and there were compromises she had to make in order to do so (and also comprises that men in her position [such as Secretary-of-State] make all the time and never are these figures so vilified).

But it’s the system, see, as Klein is hammering away at here, that is the problem. Hillary Clinton represents the futility of trying to change the system from within, a system that is rigged, flawed, gamed, and against the interests of most of us. If anything is ever going to be different—and it has to, because the earth is in peril—it’s the system that’s going to have to change.

Which is, of course, not the end of the story, but just the beginning, because how do we get there from here is the question now, but these shifts, I think, are the beginning of that. Asking questions about things we always took for granted, looking twice at parts of the status quo that make no sense at all (such as, who put Bill Gates and Bono in charge of everything?). This is such a smart, illuminating and worthwhile read, and ultimately even a hopeful one—although that might just be my silver-lining fixation showing again. And yes, you should totally read it.

March 25, 2019

Gleanings

- ‘Well, Miriam, it’s a good thing we’re Mennonites. At least you won’t get shot.’ ”

- Dealing with criticism

- White privilege is thinking you’re an oppressed minority because you can’t wear a racist symbol without being called a racist.

- Canada Reads and the gender gap.

- Antiracism is a process. Decolonial love is a process. Our love is a process. I never want it to end.

- It’s about figuring out how to be open and capacious and to let everything in and see what happens.

- Liking Books is Not a Personality [ed: this is bad news]

- Grace comes in many forms.

- Jansson is always an astonishment.

- My objection to private education is simply put. It is not fair.*

- I don’t travel with my fountain pen because it’s magic and I’m terrified of losing it.

- There’s something new and insidious about confessional-commercialism, which preys particularly on young women through the language of solidarity.*

- …how a life unfolds from what a pencil projects.

- The women who get me and get my taste are the women I follow on Instagram.*

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

*Credit for these items goes to Jessica Stanley, who publishes her own gleanings at Read.Look.Think.