September 11, 2024

Gleanings

- We all know the answers, but we need to hear them again and again. We need to listen to the work, our life’s work, most of all, because it tells us what we’re required to do.

- I’m half Pakistani, and occasionally I wonder if it’s odd that this expresses itself almost exclusively through food. Is it odd? Is it enough? Is it okay to only express part of who you are in a highly specific way?

- I know, some of us are the gatherers. The ones who reach out and invite and create the space. And some of us are the gathered. The ones that say yes, that show up, that ask, that listen, that learn. Our tables need to be filled with both. Maybe we need to try the one that’s harder for us … or not.

- In the breaks between death defying formation stunts; modern fighter jets screeching across the sky; the stately elegance of the Lancaster bomber; and lifesaving waterbombers scooping Lake Ontario and regurgitating it back, we discussed this weird fascination we share and how at odds it is with our environmental and political views.

- Nearly 100 years after Mrs. Dalloway was published, I sat on a bench and felt chills all over my body. What is this terror, what is this ecstasy. What was it? Something had happened to me beyond what was intellectual, and beyond what was emotional. It was, I concluded, so spiritual I could not put words to it.

- When my mom finally sold the house and the smell became very rare, I finally became able to smell it—there’s a few items and areas in my mom’s current place that contain it, certain cupboards I stick my head in and sniff and remember.

- This morning, at the beginning of my swim, a little silver trout jumped out of the water just beyond where I was heading, the curve of its body an opening parenthesis to my thinking.

- The cold, hard, truth about enjoying a spectacularly good day is that it is, simultaneously, someone else’s very worst day. Life’s Yin and Yang, our shared burden – knowing that the houses of joy and anguish both have revolving doors. Understanding that as we are born, someone is dying; that as we rise, someone is falling; that as we laugh, someone is crying and that, despite clinging to hope, we cannot end or even pause that cycle – we are all constantly trading places.

- I’m a very clumsy, generally inactive person but when I’m on the ice, I feel fast and light and strong. Let’s be clear: I’m a terrible skater! I haven’t figured out how to stop yet. But the feeling of being on skates is paralleled only when I’m in the water: where I suddenly understand the strength of my body and the joy in movement.

- Parents understand that the real New Year begins in September, and my mindset has shifted accordingly over the past week. My kids are back in school! The sun is setting earlier each day! What am I doing with my life?!

- What are the values we’ve internalized along the way? We are all part of our varied pasts and upbringing, but there are some values we all (or most of us) subscribe to and which are non-negotiable in our friendships and relationships. Apart from the Dream Big and Laugh out Loud type of superficial exhortations, I think the underlying message on the placard is: Be someone who others can respect and trust. Be considerate. Be genuine and kind. Be a person of integrity.

Will ‘we’ tolerate not having bananas? Will i be able to grow bananas in New England?

September 10, 2024

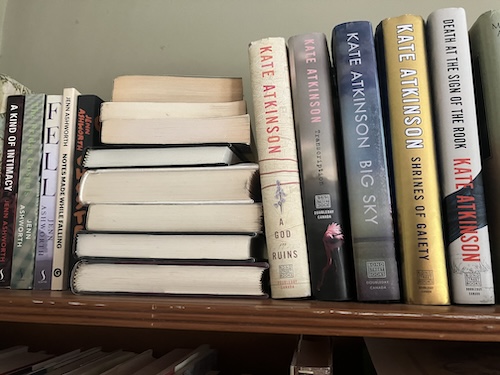

DEATH AT THE SIGN OF A ROOK, by Kate Atkinson

I didn’t know I liked detective fiction until I read Case Histories in 2005 (apparently purchased with a gift token I got for my 26th birthday!), following up my introduction to Kate Atkinson with her stunning, award-winning debut Behind the Scenes at the Museum, but I have been devoted to Jackson Brodie ever since, and the book turned me on to the genre in general, a genre of which Atkinson is very aware in this latest Brodie instalment, Death at the Sign of the Rook. And it’s true that self-aware detective fiction is having a moment. Maybe it’s not a golden age, exactly, but I’m thinking about Knives Out and Glass Onion, and Richard Osman novels, Only Murder in the Building. Death at the Sign of the Rook begins with a murder mystery weekend at a great house, Brodie himself turning up (there has been a snowstorm and he’s stranded) along with the team of actors playing the parts, and can you imagine what it would be like to run a murder mystery with Jackson Brodie in the room? Atkinson has talked about writing this book in lockdown and her desire to have some fun with the experience, which makes this a lighter Jackson Brodie than we’ve encountered for a while. What leads to the great house begins with a series of art thefts in Northern England, Ilkley, specifically, which is one of my favourite English towns (and which I only visited in the first place because I’d read about Betty’s in a Jackson Brodie novel, and Ilkley is the closest Betty’s location to where my UK family lives. And on my first visit there, I learned about Ilkley’s wonderful Grove Bookshop, which shows up in the novel twice!). Private Detective Jackson Brodie takes the case, and it overlaps with another case in which his protege Reggie Chase has worked, both cases also linked by vintage detective novels left at the scenes by a Agatha Christie-esque author called Nancy Styles. There’s a wacky family of aristocrats (as well as a reference to eccentric Englishmen not being as great as they seem, and Hugh Grant having a lot to answer for), a mysterious elder-carer (with a big bag), a vicar who has lost his faith and his voice, two sets of twins, a former soldier with PTSD and a prosthetic limb, and a murderer on the loose. And like everything Atkinson writes, the scale and pace are Shakespearean, references range from classical to contemporary, everything is just a little absurd, everyone so achingly human. I loved it.

September 9, 2024

My Stacky Authors

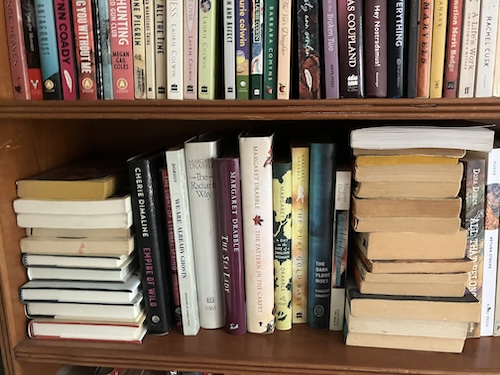

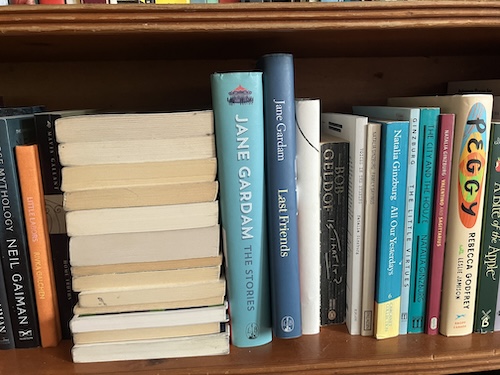

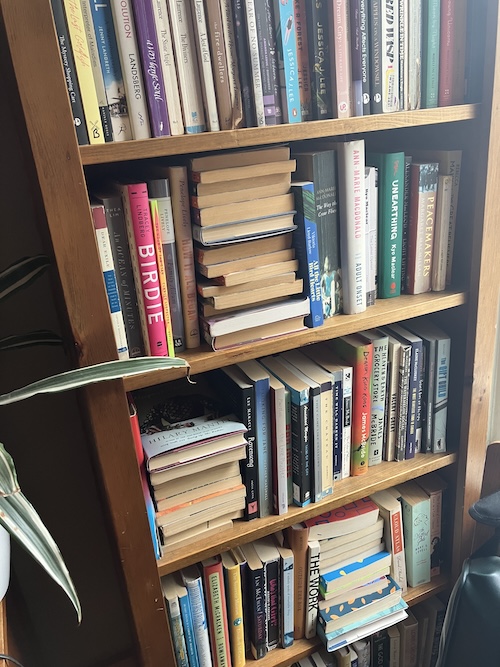

This weekend, Kate Atkinson joined an esteemed group of writers when her latest, Death at the Sign of the Rook (review to come! RAVE!), found its place in my personal library, and I determined that it was time for Atkinson to get stacky, which is what happens to authors who I like too much. And I actually kind of hate it, that I don’t get the pleasure of seeing books by my favourite authors with their colourful spines all in a row, but space is at a premium and I have to make it work (although my husband did recently suggest replacing one of our bookshelves with a taller one! SWOON!), but the only way I can accommodate the necessity of having 13 books by Atkinson on my shelf (does not even include the two of her earlier novels that I didn’t love and got rid of, which rankled the completest in me, but what can you do) is by stacking a bunch of them into a pile.

Which frees up so much space!! Room to breathe!!! Room for more books!! To be one of my stacky authors, really, is one of the largest literary compliments that I could pay you. You’d be in the company of Kate Atkinson, Joan Didion, Margaret Drabble, Jane Gardham, Penelope Lively, Hilary Mantel, Sue Miller (SO MANY L and M AUTHORS!), and Iona Whishaw.

Carol Shields is on the list now (there is more room among the Ss), for the next time shelf space gets tight.

September 3, 2024

The Summer Was An Envelope

The summer was an envelope

packed with photographs

ticket stubs

and ice cream cone wrappers

that say JOY

Waterlogged and gritty

with beach sparkle

smells like sunscreen

Moments to memories

A sacred container

Most precious souvenir

September 3, 2024

AFTER THE FUNERAL, by Tessa Hadley

I’ve never read a Tessa Hadley short story before, just her novels (most recently, Modern Love, and mercifully I still have most of her backlist before me [though they’re not easy to come by—perhaps some of them were never published in Canada?], so I was excited about her new release After the Funeral because it was a Tessa Hadley book at all, and not necessarily because it was a story collection. And then I started reading it and then spent two days walking around exclaiming, “OMG THIS BOOK THIS BOOK THIS BOOK!” because this Tessa Hadley story collection is basically 12 Tessa Hadley novels in one, each story with a ballast that is decades of history and so much perfect detail, and possibly the mind was not meant to handle so much literary goodness in a single sitting or two, because it was seriously overwhelming (and possibly I’m hormonal), but also seriously wonderful, these stories so rich and satisfying, where so much happens, where so much and said and goes unsaid.

These are stories about departures and arrivals, and also odd little intersections that occur somewhere between the two. In a recent New York Times Review of another book, Dwight Garner cited a quotation by John Edgar Wideman, who’d written, “You don’t have to be very smart to write a review of a book of short stories… All you need to say is that some stories in the book are better than others,” but I can’t even say that about this book, because they’re all wonderful. The title story is about what happens to a family after the death of a father, about how long “after the funeral” really can be. In “Dido’s Lament,” Lynette encounters her ex-husband, and reads everything all wrong. “The Bunty Club” is about three sisters, now adult, coming together upon the imminent death of their mother. “My Mother’s Wedding” features the first of a few children in this collection raised by less-than-benign neglect, and the second appears in “Funny Little Snake,” in which a woman encounters her not-so-lovable stepdaughter for the first time and then her even less charming mother. Two adult sisters meet after years of estrangement and pretend not to know each other in “Men.” “Cecelia Awakened” is about a teenage girl on holiday with her parents who finally discerns her separateness from her family, and her family’s separateness from everything else, with gut-punchingly relatable lines like, “Those girls at the next table were silly, but they were worldly, she thought, trying out that world. They were in the world and she and her parents were somehow shut out of it.” In “Old Friends,” a tragedy could possible bring together a couple together, but it turns out the absence of the third in their triangle over pulls them apart. A dream of childhood is still as vivid to a grown man as the present moment in “Children at Chess.” “The Other One” is an epic in under 30 pages, the story of a woman who encounters a figure from her father’s past in an entirely different context. “Mia” is a portrayal of glamour from a teenager’s point of view and finally “Coda,” a lockdown story of loneliness, loss and longing for connection.

Singular, vivid and compelling, every last one of them. This book came out ages ago in the US and UK and I’m glad to finally get a chance to read it. It’s one of my favourite books of the year.

August 28, 2024

Peggy, by Rebecca Godfrey, with Leslie Jamison

The two stories behind Rebecca Godfrey’s novel Peggy are interesting, first the biography of Peggy Guggenheim herself, the iconic art collector from a famous American family, and then Godfrey’s own experience working to complete her novel about Guggenheim before her death from cancer in 2022 and how, when she was unable to do this, her friend Leslie Jamison stepped in to finish the book. But as a reader who knows almost nothing about Peggy Guggenheim and who hasn’t read Godfrey’s work widely (I think I read Under the Bridge a long time ago), neither back story seemed necessarily resonant or pressing to me. Would Peggy be a book I really needed to to pick up?

But then I did, and I couldn’t stop reading.

And I finally understood the weight of Jamison’s task, and what a loss it would have been if this novel had never seen the light of day, because it’s just wonderful, imbued with a kind of magic, rich and artful, the prose full of light and surprises, Peggy Guggenheim so entirely alive on the page. We meet her at the beginning of Chapter 1, “Striped and shot, the tiger lay flat, and I stretched my hungry body across him. He was part treasure, part prey. Though we had so much, I often ignored the chaises and satin chairs, instead gathering my book and lying upon this tattered dead animal.” And it pretty much goes on like that, both extraordinary and so matter-of-fact, Guggenheim’s remarkable experiences including her provenance (“I am the daughter of two dynasties”), that her father went down with the Titanic, her life in 1920s’ Paris, being photographed by May Ray, a love affair with Samuel Beckett, that she was a patron of artists including Djuna Barnes and Emma Goldman, and would build a modern art collection that would become famous throughout the world.

A tragic figure in some ways, Godfrey also shows that Peggy Guggenheim was full of life and spirit, that she would eventually come into her own power, but some losses would never be overcome, and that she was a marvellously imperfect person, beyond ordinary (which is what she so longed to be) but also so achingly human, and that vitality is this novel’s chief appeal, that fiction can seem so real . Even fiction that’s messy and sometimes strange, mistakes and inconsistencies popping up throughout, not overwhelmingly but you notice. At the beginning we learn that Peggy and her sisters were living at the Waldorf-Astoria, but it’s the St. Regis on the following page (and in actuality, according to my internet sleuthing), and initially I was thrown by this—Jamison opted to leave most of Godfrey’s manuscript untouched, to not presume to edit, which seems like a strange call until you come to the line where Peggy is using her eye and describing some Impressionist works to her father: “These paintings look unfinished, but they’re deliberately haphazard.” And then her father points to the paintings and tells her that “all [she] need[s] to know…is that this is life.”

Peggy Guggenheim made art her life, and her life was art, and so too is this strange, beautiful and heartrending novel. Peggy is such a remarkable literary achievement.

August 20, 2024

SLOW DANCE, by Rainbow Rowell

My friend @meli_mello1 was a Rainbow Rowell fan, and when I was reading Slow Dance this weekend I kept thinking about how unfair it was that she’d never be able to read it, all those things a person is robbed of when she dies at 45 (not least of all, the chance to see her three daughters grow into the people she was raising them to be). The unfairness of this inspiring me to once again sign up for the Turning the Page on Cancer Readathon, for which I’m hoping to raise $1000 for Rethink, supporting young women diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. I hope you will consider supporting my efforts!

And wow, SLOW DANCE, just a beautiful, impossible, agonizing-at-times love story about two messed up weirdos who everybody always assumed were together in high school, but they were just friends. “Just friends” who were everything to each other, and so terrified of communicating that truth and daring to take things any further for fear of messing it all up and wrecking everything that they mess it all up and wreck everything. They both have different dreams of how they’re going to make it out of their North Omaha neighbourhood, Shiloh through Broadway stardom, and Cary through a career with the Navy, and how to weave those dreams together seems absolutely unworkable, and then they don’t even speak for 14 years until a reunion at their friend Mikey’s wedding, Shiloh divorced and a mother of two, Cary still dealing with his dysfunctional family, Shiloh living back at home with her mom. It’s like nothing has changed, but also everything has changed, and will it be possible for these two to find a way forward (particularly as they’re both determined to fling obstacles in their way so they won’t ever have to stumble upon such a thing unaware).

I loved this book. I loved these characters. A time machine, without the metaphysics. How did we get from there to here, and where are we going after?

August 16, 2024

Good Time

Am I having a good time because the books are so good, or are the books so good because I’m having a good time?

The proverbial question, one that seems more pressing when I’m in a funk and the books are terrible, but it’s worth asking too when I just keep opening one fantastic novel after another. And it’s true that our summer has been quite glorious, last week ending a string of four delightful getaways around Ontario, each one with reading as sparkling as the lakes were. A month ago, I was raving to you about Catherine Newman’s Sandwich, a read that felt like the springboard to my summer, and now I’m back with another pick that read its way straight into my heart, so much so that I’m imploring everybody around me to read it, read it, read it. (So far, my husband and daughter have done so, and loved it too, along with Barack Obama, so I’m currently working on a 100% approval rating.)

I read Liz Moore’s novel God of the Woods during a camping trip to Pinery Provincial Park on Lake Huron, and I thought I knew what I was getting into. I’ve read books about missing girls before, you see, and I’ve read books set at summer camps, and I know how such a setting can be both creepy AND perfect for exploring class divides, and this is also a book about a great house belonging to a wealthy family—naturally the house has a name, and that name is, absurdly, “Self-Reliance.” I’ve read detective fiction before too—the detective working the case of the missing Barbara Van Laar in this book is a young woman eager to prove herself, whose talents are undermined by her colleagues. This novel, I supposed, would be just a book jam-packed with all my favourite literary elements. And it is, it really is, but what makes it so exceptional is what Moore does with those elements, how she manages to take these familiar devices and tell a story that’s suprising and subversive, like nothing I’ve ever encountered before. How the dripping blood on the cover is in fact dripping paint, is the kind of thing I’m talking about. A thumb to the patriarchy, wonderfully queered, and so fiercely feminist, plus it goes down a treat. It’s so fresh, and so interesting. (Read it, read it, read it.)

(This post was a Free Post on my Substack this week! Sign up to receive Pickle Me This directly to your inbox.)

August 12, 2024

The Holiday Reading Round-Up

If appears like I’ve spent the last six weeks mostly on vacation, YOU WOULD BE CORRECT, and what a trip it’s been, so many good books. And some of the books I read last week on our cottage holiday in Haliburton will be familiar if you read my July Substack Essay, “How to Build a Summer Reading List,” beginning with Family Pictures, by Sue Miller, who has only been a summer holiday reading mainstay for me only since 2020, but it feels like since forever. Like so many of her books, this one is a complicated family saga spanning decades, about a marriage that becomes derailed with the arrival of a son who is “different,” Randall, the third of six kids, eventually diagnosed with autism. The problem with this book is that Randall is a device instead of a character, the book and its characters pre-supposing any notion of Randall could be a person with his own consciousness, let alone narrative perspective. But it’s an interesting treatment of how autism was considered in the 1950s, and the ways in which mother were to blame for their children’s diagnoses. Even without Randall, the marriage in this story would have been a complicated one, however, and this nuanced treatment of family dynamics (especially from the point of view of their adult daughter who eventually comes to view her parents, and all their mistakes, with some sympathy) is what makes the story so interesting.

My next pick was Dominick Dunne’s A Season in Purgatory, a totally battered copy I bought for three dollars at The World’s Smallest Bookstore near Kinmount on the way to our cottage. I can’t remember when Dominick Dunne came into my life, but I think it was via his Vanity Fair columns, which then led to me obsessively reading his fun and trashy novels (which, like Sue Miller, I remember lying around our house in paperback during my childhood). I’ve not read him for years though, but I’m on wait-list to receive his son’s memoir The Friday Afternoon Club, so thought a reread would be meaningful in the meantime, and I loved it just as much as I ever did. What is most remarkable is that I have been totally oblivious and only learned a few weeks ago (while listening to Griffin Dunne on a podcast) that Dominick Dunne was gay, and I really can’t believe I didn’t get it, because in the book (whose narrator is a fictionalized version of Dunne) IT’S NOT EXACTLY SUBTLE, but I also can believe I didn’t get it, because I spent most of my life in the most heteronormative bubble….

Next I reread The Joy Luck Club, which came up for me when I published my own book about women’s friendships and someone mentioned it to me, and I realized I hadn’t read it since everybody was reading it in the early 1990s. When I was, of course, a literal child, and I see now how the most interesting parts of the story would have gone over my head at that point. There is a line from Elisa Gabbert’s new book about some books reading up best when you’re too young to really understand them—her example was The Catcher in the Rye, and I concur—but The Joy Luck Club was not one of them, a story of mothers and daughters, and women’s lives, and very complicated friendships. Rereading was a lesson in how much of my earlier reading life must have gone straight over my head.

Next up was A Kind of Intimacy, by Jenn Ashworth, an English writer whose depictions of Lancashire and the northwest have been really important to me. This is the fifth book by her that I’ve read, her debut novel, and it was as easy to read and absolutely uncomfortable (seemingly a contradiction) as all her novels are. This one is set in my husband’s hometown of Fleetwood, Lancashire, which gets described as “dismal,” which it can be, particularly if you’re any of the characters in this book. Annie is an unreliable narrator hoping to put the trauma and violence in her past behind her and make a brand new start, but she becomes strangely fixated on her new next door neighbour and things go awry in ways that will even surprise the readers who’ve seen her coming.

Next was another reread, Brother of the More Famous Jack, the 1982 award-winning debut novel by Barbara Trapido, which was like nothing I’ve ever read before, and so when I read it for the first time, I was mostly baffled. Trapido’s novels are ribald and theatrical, not exactly shaped like English novels at all, and this coming-of-age story unfolds over more than a decade, as daughter of a grocer Katherine becomes enveloped into the eccentric Goldman family. Absolutely nothing is above reproach in this novel, where characters joke about rape and the Holocaust, and the death of a baby and stay in a mental hospital are passed in a few paragraphs (albeit frightfully felt). Politically correct, this novel is not, but neither is it boring or derivative. Having read three other of Trapido’s works, I was finally in a place to properly appreciate it.

And Marian Keyes’ Again, Rachel, was a fairly fitting book to read after it, another ribald story that touches on infant loss, and oh my goodness, Keyes is brilliant. Such a sparkling sense of humour, but the books are containers for such difficult and weighty subjects, and she does such justice to them. There were so many threads in this novel that it seemed impossible she’d work them just right, but she did. These books are so wonderful, and complicated, full of nuance, and worthy of serious attention. They’ve got heft, but they’re also fun to read, which is the only remotely fluffy thing about them.

And then I picked up Commencement, by J. Courtney Sullivan, which touches on the same lack of regard for novels about women that I alluded to in the previous paragraph, except that this is a debut novel and Sullivan is trying to prove herself, wanting to be taken seriously, while Keyes has no fucks to give nineteen novels in. I’d read Sullivan’s novel Maine last year, a summery pick, and enjoyed this too, their contemporary feel but gesture toward a saga.

And finally, Iona Iverson’s Rules for Commuting, by Claire Pooley, which was our audiobook for the drive, and we all loved it so much. It can be challenging to find a pick to suit readers from ages ranging from 11 to 45, and it’s mostly Agatha Christie books that get us through, but I was desperate for a book that wasn’t an Agatha Christie, so decided to take a chance on this one. Which, hilariously, begins with an Agatha Christie epigraph and some fascinating allusions to Murder on the Orient Express, which has been one of our faves. This novel is very different, of course, but we adored it, so utterly engaging, so laugh out loud funny, and I don’t think I’ve ever enjoyed an audiobook more. Warmhearted and a little edgy at once—we were all delighted.

And one more, because I can’t resist. We just passed the four year anniversary of Taylor Swift’s Folklore, an album that felt like such a gift during that very hard year and its cruel summer, and so we were listening again because it’s such a midsummer album, and also the song “August,” which has been in my head since the calendar turned. Swift is one of my favourite storytellers, the Bruce Springsteen comparison totally apt. Lines like, “You heard the rumour from Inez, you can’t believe a word she says—most times, but this time it was true.” Or, “Back when we were still changing for the better, when wanting was enough, to believe it was enough. To live for the hope of it all. Cancelled plans just in case you call.” Songs like “Mirrorball” and “Epiphany”—so much feeling. So many stories. We were listening again, when we weren’t listening to Iona Iverson, and I just felt so glad to live in a world where there is such thing as Taylor Swift.

August 1, 2024

SHARK HEART, by Emily Habeck

One of my most frequent experiences of nostalgia is biblio-nostalgia, the longing to be returned to a particular book in a time and place that felt especially sublime. The August I read MALIBU RISING at a rented cottage and could not put it down, the long weekend two years ago when I read Jennifer Close’s MARRYING THE KETCHUPS at the beach, the particular camp chair I was slumped in years ago as I was hastily turning the pages of Amber Dawn’s SODOM ROAD EXIT (lesbians, vampires and abandoned roller coasters on the shores of Lake Erie, oh my!). And yes, while it’s only been a month, I’m still not over having read Shelby Van Pelt’s REMARKABLY BRIGHT CREATURES on our camping trip over the Canada Day long weekend and—especially as we departed on another camping trip last Saturday—I felt the desire to have it happen all over again, the perfect book in the perfect place and time. But this is the kind of experience it’s impossible to manufacture; it either happens or it doesn’t.

But it did, because en-route to our campsite on the banks of Lake Huron, we stopped for in the town of St. Marys, precisely because it was home to a bookshop I’d never visited before, Betty’s Bookshelf, and the town turned out to be wonderful, the bookshop itself just absolutely perfect, stocked with excellent picks (including my own novel!), and every single member of my family left with a title we’d never heard of before.

Which for me was SHARK HEART, by Emily Habeck, enthusiastically recommended by bookseller Wren, a book that MIGHT have been a hard-sell considering its premise (this is a novel about a newlywed couple whose plans go awry when the male partner is diagnosed with a rare disease in which he mutates into a great white shark, yup, really), but Wren promised me that this was a novel about love, and grief and life, and the mutation is a metaphor of sorts, and then I read the back and saw a blurb by none other than Shelby Van Pelt, and decided that this might be the closest I’d come to reading REMARKABLY BRIGHT CREATURES for the first time all over again.

I will say that this is a very different kind of book, far more strange and lyrical, if similarly preoccupied by the desires of sea creatures and blurry lines between us and them, but it similarly hit just perfectly, and as I devoured it (I sound like a great white shark now; it was less bloody than that, I promise). Like Ann Patchett’s TOM LAKE, it’s also about a production of OUR TOWN, which I’ve now even read. This is a novel about the paths in life that take us places where our loved ones can’t follow, about how to face the unimaginable, about how some people are unlucky over and over, terrible patterns repeating, the unfairness of fate, the beauty that’s possible anyway.

I loved it. You should read it. Thank you to Betty’s Bookshelf’s Wren.