December 30, 2013

In With the New

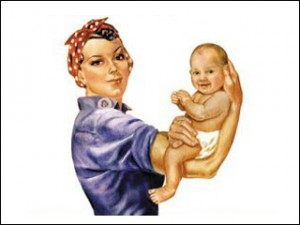

If this is a year in pictures, 2013 only needs this one for me. Not just my favourite image of the year but perhaps my favourite image of all time, my baby brand new, sticky, shrieking and naked, yanked out into the world one day shy of 42 weeks in utero. The image I never got to see when Harriet was born, and a sign that this might be our chance to right what went wrong the first time we had a baby. Not the birth I’d envisioned, cold and sterile, my body split in two, and we were so disappointed. (It is true that whenever anyone has had a baby since, I have cried because Iris’s birth was another c-section.) And yet, this image for me was a glimpse of possibility, that this could be another story. Iris’s birth was a new beginning in so many senses–of her life, course, and of our family as four. But it was also for me a rebirth of myself, that self that had been so shattered when I became a mother for the first time. The second time, however, has been like coming full circle, a journey to somewhere familiar and brand new.

This year has reassured me even with its challenges. I used to worry that I was only a happy person because circumstantially I’ve been extremely blessed, and while I am blessed and I also think I have a chemical disposition for happiness (another blessing, though after about eight more weeks of winter, I will be telling a different story), I managed moments of happiness too in times of stress and enormous fear. I think of a week in March whilst we were awaiting biopsy results, and how we spent the week so gloriously, but then the sun was shining and I’d decided to believe in the odds in my favour (and so they were). But still. I may be braver than I think. I am also grateful that my worst fears were averted. Further, I have learned a lot about things going wrong and how these things don’t necessarily signal, quite literally, the end of the world.

“Over time, I’ve come to understand that when Jamal says that a situation is normal, he means that there are flaws in the cloth and flies in the ointment, that one must anticipate problems and accept them as a part of life. Whereas I’ve always thought that things are normal until they go wrong, Jamal’s version of reality is causing me to readjust my expectations for fault-free existence and to regard the world in a more open fashion.”–Isabel Huggan, “Leaning to Wait, from Belonging

I stood on the cusp of 2013 with a great deal of uncertainty–I was partaking in a freelance writing project that would be quite intense and something I’d never done before, and I knew there would be a newborn baby in my life again, which seemed a horrifying proposition. But I’ve met both these challenges quite impressively, and it is funny that what caused me real problems during the past year was that cystic tumour growing up on my thyroid when it had never even occurred to me that I had a thyroid. It seems you never do know, which is a promise as much as something to fear.

The world has smiled on us a lot this year. First, with the birth of our strong, healthy baby; with our brilliant summer as Stuart had 12 weeks on parental leave; with Stuart being promoted to a new job that makes him so very happy upon his return to work; with a book contract for The M Word, which I am so very proud to have my name attached to; with Harriet who manages to be as wonderful as she is annoying (and that’s huge). I like people who are 4 years old. I am lucky to have Stuart in general, who delivers my tea in the morning. I am grateful for him, and to our families for their love and support. I am also grateful for our new queen-sized bed, which means that Iris sleeping with me every night (and sometimes the “sleep” is elusive) is not nearly as bad as it sounds.

I started writing when Iris was just a few weeks old, my mind and imagination anxious to be exercised. I hadn’t written short fiction for so long–the previous year had been spent on The M Word, year before that on a novel forever unfinished that has served its purpose but I’m done with it. But since then, I’ve been busy, and I do hope that some of that productivity turns into publishing credits in the year ahead. I’ve sent out submissions, which is the part of the battle I have any control over. That and working hard on my pieces of course. I’ve been focussing on revising and getting feedback, both of which I’d shrugged off for too long, out of fear, I think, and habit (too much blogging). I am proud of my book reviews this year, my Ann Patchett review in The Globe, of Hellgoing in Canadian Notes and Queries, and Alex Ohlin’s two books at the Rusty Toque. I am also happy to be reviewing kids books for Quill & Quire. I continue to be so grateful for the opportunity to promote great Canadian books through my job at 49thShelf–come March, I’ll have been working on the site for 3 years.

My New Years resolutions (in addition to writing and revising and submitting) is to not to any of the annoying things I complain about authors doing once I’ve got a book in the world myself. I’ll be writing more about this in a few weeks time. Will be interesting and educational to see it all unfold from the other side of the page.

My reading resolution of 2013 was to read more non-Canadian books, which is kind of a weird resolution but I was stuck in a CanLit bubble and it was making me crazy. So I am pleased that I read outside of that bubble (and that I’ve read 4/5 of the best fiction of the year according to the New York Times). There is not reading what everyone else is reading but also reading totally out of the loop, and I feel that in 2013, a balance was struck. (I just finished reading another top-rated book of 2013, A Constellation of Vital Phenomena by Anthony Marra, which was so wonderful. I am so glad I didn’t let it pass me by.) For 2014, I would like to put a focus on reading books in translation, because really “the novel” is so much richer than I’ve glimpsed by English language focus.

This year I’ve read 92 books or thereabouts, which is far fewer than I’ve read it years and years. But I’ve also read more long, long books than I have in recent years and taken my time and enjoyed them. I also know that I’ve read about as much as has been humanly possible, save for the problem of my possible addiction to twitter (which I’m working on) so I am content with the total. Content also because the books I’ve read have been so extraordinary. (I have also abandoned a ton of books in 2013, and I am totally happy with that.)

Over the past few days, we’ve been busily decluttering the corners of our apartment. We’ve made a commitment to stay in this place we love so much as long as it’s comfortable to live here, and so we’re working on that comfort and making space by clearing away all the things we don’t need. And suddenly, our house is bigger, airier, and cleaner than we thought it was–the space! (Certainly, getting the fir tree out of the living room helps a little bit. Also getting rid of that box of plates in the kitchen that hasn’t been opened since the last time we moved.)

Out with the old then and in with the new, and it’s all so refreshing, full of possibilities. Though the greatest thing about the situation, of course, is just how pleased are we to be where we are.

December 15, 2013

Presuming an ample supply of the things you like and need

From “Processing Negatives: A Big Picture of Poetry Reviewing” by Helen Guri on the CWILA Blog:

“But, as a woman poet who increasingly reads the work of other women poets, I know that a too-large proportion of the books I love don’t get their due in the public sphere. I cannot begin to tell you how many “underrated” poets presently occupy places of honour on my shelf. I say this not to diminish the books I read or write about, nor the marketing skills of their authors, nor to suggest that I write reviews or read books out of pity—I am at heart a lazy hedonist, and do in my unpaid hours basically only what brings me immediate pleasure—but to question the context in which poetry books by women and other “minorities” are received…

Male reviewers, by the CWILA stats at least, are more likely to have their tastes taken care of—assuming, as I think is reasonable based on my experience studying friends’ bookshelves, that tastes often diverge by gender. And really there is no better illustration of this than the relative freedom many of these reviewers seem to feel, the leftover energy they seem to have, to express their dislikes too. Singling something out and saying “no, not this” is a gatekeeping behaviour. It presupposes an ample supply of the things you like and need—people don’t generally demand to have the peppers taken off their pizza if they aren’t regularly being fed.”

March 18, 2012

On books, "buzz" and magic

“You can almost always find chains of coincidence to disprove magic. That’s because it doesn’t happen the way it does in books. It makes those chains of coincidence. That’s what it is. It’s like if you snapped your fingers and produced a rose but it was just because someone on an aeroplane had dropped a rose at just the right time for it to land in your hand. There was a real person and a real aeroplane and a real rose, but that doesn’t mean the reason you have the rose in your hand isn’t because you did the magic.” —Among Others, Jo Walton

It’s like magic, the way good news of a book spreads. I’m currently reading Jo Walton’s Among Others because at our last book club meeting, Deanna couldn’t stop talking about it, and then Trish tweeted, “Dying to get on the streetcar so I can get back to reading Jo Walton’s Among Others“, and this is the kind of buzz I listen to. It’s real and you can’t buy it, but I trust it because it’s the sound of real people talking about a book that’s made a connection.

But it’s not magic, of course. It’s a chain of coincidence that begins with a writer creating a work that is really good, or sometimes a work that is not very good but happens to be exactly what readers are hungry for. And then the work drifts out into the world, and of course it helps to know a lot of people well-placed to help the drifting, to have a great cover design, be published by a press that newspaper editors pay attention to, to be photogenic and/or notorious (or fictional), to have a lot of time to twitter, and a knack for connecting with your audience. But then I’m thinking of a book like Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin where almost none of that happened, and the book caught on fire. What happened with that book was the most amazing chain of coincidence, a force onto itself, and no one ever could have made that happen.

In less magical terms, I despair when I listen to men on the radio talking about an invasion of Iran or moving the economy forward as though anyone actually has any understanding of or control over how matters of war or economics transpire– these things take on unforeseen trajectories and are carried by their own momentum. You can’t plot these matters the way you plot a book, and nor can you plot a book’s reception either. I recently read a comment by an author stating that he appreciated the way that social media gives him control over what happens to his books once they’re published, but that control is an illusion. The magic is going to happen or it isn’t, and it’s unfair expectation on an author to make him think he can steer it either way, or that he’d feel responsible when magic fails to occur (except perhaps for having written a book that wasn’t extraordinary or even good. I come across a lot of terrible books in my travels. It is my opinion that more writers should be feeling such a burden these days).

Sometimes the magic should happen and it doesn’t. For example, it blows my mind (and in a bad way) that there are books on this that anybody hasn’t read yet. It’s unjust. Or that Lynn Coady’s The Antagonist didn’t win a major literary award last autumn (though magic did happen there. People loved that book). It kills me when the books I love don’t take, but it’s the way it goes, and it’s in nobody’s hands. But then I go declaring Carrie Snyder’s The Juliet Stories as one of the best books of the year, the CBC concurs, and the book is getting rave reviews everywhere. This is what buzz is: a chain of coincidence that originates with a book that is awesome. (And now here, it’s your turn: buy it.)

Which is not to say that writers are powerless or that book marketers would be best sitting idle. Book marketing is a tool, and so is social media, and both are always going to aid the process. I recently purchased Emma Staub’s story collection Other People We Married because on one strange morning, she had turned up in every hyperlink I’d clicked on and somehow that managed not to be annoying. Now Straub is well-connected, which does help– I followed her on twitter after a recommendation by Maud Newton, who is a good person to know, I’d say. But mostly importantly, in none of the links I clicked on was Straub telling me how fantastic she or her book was. In one, she was using her experience as a bookseller to advise writers on “How to Be an Indie Booksellers Dream”. In another, she was included in Elissa Schappell’s “Books With Second” Lives feature. And then there was this. Such a chain of coincidence, I found, that obviously the universe was telling me to buy this book. And so I did.

So the writer is not powerless. But here it is, in two of these links, the magic had already happened– the book had connected with readers and they were telling me about it. In the other, Straub was putting her name and face out there, but doing so by participating in a wider community of readers and writers, giving them something other than a sales pitch.

Writers: stop tweeting the same links to your reviews over and over again (unless, perhaps, you’ve just been reviewed in the New York Times), stop spamming your followers, you don’t need to respond to every blogger’s review (and especially not if it’s a bad one), give your potential audience a reason to be interested in you besides the fact that you’ve written a book you want them to read. Social media is a conversation, and nobody likes anyone in a conversation who only talks about themselves.

But at a certain point, the writer has to take a step back and just let it happen. Magic can’t be orchestrated.

**

Speaking of magic, we high-fived over our pancakes this morning as The 49th Shelf received a shout-out on CBC’s The Sunday Edition in a discussion about the state of Canadian publishing. It was glorious.

March 1, 2012

A cool thing

A cool thing that happened lately was discovering bloggers at The Book Mine Set and Perogies & Gyoza reading my short story “Georgia Coffee Star”. They both had lovely things to say about my story, and urged other readers to check it out. How lovely to see one’s work alive in the world, and to learn that readers are enjoying it. It means a lot to me.

December 18, 2011

I had a plan once

I had a plan once, that I’d have a book before I had a baby, but it turned out that I had a book that wasn’t very good, and one can put off having a baby forever. So I had a baby, and then I wrote a lot of other things, but it’s hard to write a new book when one took you wrong before. The first (or, ahem, second) time around, you can fool yourself into thinking the objective is just writing to the end, but there’s more to it than that. It’s hard to write a book once you’ve learned that your best might not be good enough, that hard work really can come to nothing, that the doubting voices in your head might be telling you the truth. It took me three years (and many false starts) to get to the point where I was ready to start again, but once I did, I found myself tremendously liberated. There was no fear of failure, because I’d done that before and survived, and I could do so again if required. And having my illusions shattered, I knew there was no other reason to be writing another book except for the sheer love of doing it, and love it, I truly did.

I had a plan once, that I’d have a book before I had a baby, but it turned out that I had a book that wasn’t very good, and one can put off having a baby forever. So I had a baby, and then I wrote a lot of other things, but it’s hard to write a new book when one took you wrong before. The first (or, ahem, second) time around, you can fool yourself into thinking the objective is just writing to the end, but there’s more to it than that. It’s hard to write a book once you’ve learned that your best might not be good enough, that hard work really can come to nothing, that the doubting voices in your head might be telling you the truth. It took me three years (and many false starts) to get to the point where I was ready to start again, but once I did, I found myself tremendously liberated. There was no fear of failure, because I’d done that before and survived, and I could do so again if required. And having my illusions shattered, I knew there was no other reason to be writing another book except for the sheer love of doing it, and love it, I truly did.

I started this first draft in September of 2010, and my goal for 2011 was to finish it. The manuscript was finished a few months ago, but it was only this morning that I printed it out (on green cardstock, because what else am I going to use it for?): 128 pages, 65,000 words, absolute proof of goal achieved. And you know what? It’s actually pretty good. I’m looking forward to reading it over the next few weeks, red pen in hand, and then beginning my second draft with a blank page, new document, and trying to make it as good as I possibly can. Which is now my goal for 2012, as well as to enjoy every step along the way.

But in the meantime: hooray for right now. Another goal is to remember that hurdles are milestones.

December 7, 2011

On being in a book (!)

In 2007, my friend Rebecca Rosenblum had her story “Chilly Girl” published in the Journey Prize Stories 19. And I will never forget how exciting it was to go into the Book City at Yonge and Charles (which is, like many other bookstores, no longer with us) and her buy her book off the shelf. Rebecca’s first story collection came out the following year, and the whole thing was so exciting, but to me, nothing ever topped the excitement of that first actual book with Rebecca’s story in it.

In 2007, my friend Rebecca Rosenblum had her story “Chilly Girl” published in the Journey Prize Stories 19. And I will never forget how exciting it was to go into the Book City at Yonge and Charles (which is, like many other bookstores, no longer with us) and her buy her book off the shelf. Rebecca’s first story collection came out the following year, and the whole thing was so exciting, but to me, nothing ever topped the excitement of that first actual book with Rebecca’s story in it.

I also remember that a bird shat on my hand as I was walking down Charles Street toward the bookstore, and the good luck that I was wearing a mitten at the time, and I remember thinking as I contemplated good luck, “One day, I want to be in a book like that one, with binding, and editors, and everything.”

Last night, a crowd of some of the very best people I know came out to the launch of Best Canadian Essays 2011, and I proceeded to have 2 pints of beer and fall even more in love with everyone. (I had to stop at 2. At 3 pints, I get feisty and start offending people even more than usual.) It was really, truly a spectacular night, and I felt honoured that my essay was chosen, that it was published along with so many other wonderful pieces, and that so many faces in the crowd belonged to people I love as I read from “Love is a Let-Down.”

I’ve got a sense of proportion about these things. I know the pond is big and I am small, but I’m still in awe of the fact that I get to swim in it. And I really would like to publish a book of my own one day, but who among us doesn’t have a dream like that? In the meantime though, I’m feeling a tremendous amount of satisfaction about an accomplishment that bird-shit on my mitten may have portended years ago: I am in a book. And more over, it’s a pretty great book.

I’ve been revelling in every bit of all this, and it feels as wonderful as I imagined it would be.

March 27, 2011

That annoying thing that women do

This is not so important, but it occurs to me that I’ve been doing that annoying thing that women in my situation tend to do. Making comments about professional tea-guzzling and reading with my feet up, and though these things are practically absolutely true, they’re not the whole picture. I have a tendency toward self-deprecation anyway (it’s just easier that way), and I also don’t find the demands of stay-at-home motherhood particularly arduous, mostly because I have only one child who sleeps a lot, and a small house that requires little maintenance (plus we keep our standards very low). Life for me is very good, though to play the role of the idle hausfrau would be disingenuous (though this does not change the fact that tedious maneuvering really is the story of my life. Let that fact stand).

This is not so important, but it occurs to me that I’ve been doing that annoying thing that women in my situation tend to do. Making comments about professional tea-guzzling and reading with my feet up, and though these things are practically absolutely true, they’re not the whole picture. I have a tendency toward self-deprecation anyway (it’s just easier that way), and I also don’t find the demands of stay-at-home motherhood particularly arduous, mostly because I have only one child who sleeps a lot, and a small house that requires little maintenance (plus we keep our standards very low). Life for me is very good, though to play the role of the idle hausfrau would be disingenuous (though this does not change the fact that tedious maneuvering really is the story of my life. Let that fact stand).

I thought of an excerpt from a review I read recently of Shirley Jackson’s work (“Dye the Steak Blue”  by Lidija Haas), and though I’m no Shirley Jackson, obviously, I can understand why Betty Friedan was annoyed by her, and I’m setting the matter straight here because I’m a little annoyed at myself. From the review: “Friedan called [Jackson] an Uncle Tom, one of those women who disingenuously portrayed themselves as ‘just housewives’, ‘revelling in a comic world of children’s pranks and eccentric washing machines’, affecting to find a challenge in the most routine chores and concealing the ‘vision, and the satisfying hard work’ which went into their proper vocation, as writers.”

by Lidija Haas), and though I’m no Shirley Jackson, obviously, I can understand why Betty Friedan was annoyed by her, and I’m setting the matter straight here because I’m a little annoyed at myself. From the review: “Friedan called [Jackson] an Uncle Tom, one of those women who disingenuously portrayed themselves as ‘just housewives’, ‘revelling in a comic world of children’s pranks and eccentric washing machines’, affecting to find a challenge in the most routine chores and concealing the ‘vision, and the satisfying hard work’ which went into their proper vocation, as writers.”

So though my washing machine is terribly eccentric (in fact, it would be better termed a “kind-of washing machine” and it sometimes smells like it’s about to catch on fire), and though I do take pride in managing my household (which is no small task, as anyone who’s ever lived in a household realizes), I only do housework when my child is awake, and whenever she’s asleep, feet-up or otherwise, I am usually at work on something related to writing. I work very hard at this blog, on my freelance assignments, at reading thoughtfully and writing book reviews that communicate this, at writing fiction, at creating new projects and at being a part of a wider creative community. At managing to contribute to our household income through my creative work. And I absolutely love all of it. It is tremendously important to me.

So this is not to be the writer’s equivalent of those wretched Facebook statuses that made me hate mothers just as much as the rest of society does (“So you ask, do I work? Uh yes, I work 24 hours a day. Why? Because I am a Mom… I don’t get holidays, sick pay or days off. I work through the DAY & NIGHT. I am on call at ALL hours. re-post if you are a proud Mommy “). I just think I was selling myself short before, affecting a little too much, which isn’t surprising– there is unease that comes with being a stay-at-home mother. But I am also a feminist, and I’d never want to let Betty Friedan down.

Also, I much appreciate the friends who’ve been so supportive about last week’s news. Since the shock has worn off, we’re very positive about things, and even grateful that the right decision has made, in particular because it’s one we might not have been brave enough to make on our own.

January 24, 2011

On Literary Blogs: A Passion for Reading

One of the most wonderful things that ever happened to me was being asked to speak about literary blogs on a panel for an “Arts Matters” forum, hosted by Their Excellencies, Governor General Michaëlle Jean and Jean-Daniel Lafond in December 2008. I traveled to Ottawa by train, arriving in an incredible snowstorm, and in spite of the weather, a good crowd turned out to the forum at the Ottawa Public Library. My adoration for my fell0w panelists was solidified on the trip back to Rideau Hall, and the group of us spent the next day and a half as the Governor General’s guests there, attending the Governor General’s Literary Awards the following evening. It was a magical experience, unreal to fathom now. Even more so now that we have a new Governor General and the old website has come down, my address on literary blogs along with it.

One of the most wonderful things that ever happened to me was being asked to speak about literary blogs on a panel for an “Arts Matters” forum, hosted by Their Excellencies, Governor General Michaëlle Jean and Jean-Daniel Lafond in December 2008. I traveled to Ottawa by train, arriving in an incredible snowstorm, and in spite of the weather, a good crowd turned out to the forum at the Ottawa Public Library. My adoration for my fell0w panelists was solidified on the trip back to Rideau Hall, and the group of us spent the next day and a half as the Governor General’s guests there, attending the Governor General’s Literary Awards the following evening. It was a magical experience, unreal to fathom now. Even more so now that we have a new Governor General and the old website has come down, my address on literary blogs along with it.

So I’ve reposted it on my own site, for posterity. You can read it here.

November 23, 2010

Talking In Circles and Coming Full Circle: Talking About Talking About Motherhood

Marita Dachsel’s first book of poetry All Things Said & Done (Caitlin, 2007) was shortlisted for a ReLit Award. Her poetry has been published in many Canadian journals, in a recent chapbook, Eliza Roxcy Snow (red nettle press, 2009), and as part of Vancouver’s Poetry In Transit Program. Currently, she is working on a novel as well as finishing Glossolalia , her second poetry book, in which she explores the lives of the polygamous wives of Joseph Smith, founder of the LDS Church. After twelve years in Vancouver, during which she received both her BFA and MFA in Creative Writing at UBC, she now lives in Edmonton with her husband, playwright Kevin Kerr, and their two sons.

Marita Dachsel’s first book of poetry All Things Said & Done (Caitlin, 2007) was shortlisted for a ReLit Award. Her poetry has been published in many Canadian journals, in a recent chapbook, Eliza Roxcy Snow (red nettle press, 2009), and as part of Vancouver’s Poetry In Transit Program. Currently, she is working on a novel as well as finishing Glossolalia , her second poetry book, in which she explores the lives of the polygamous wives of Joseph Smith, founder of the LDS Church. After twelve years in Vancouver, during which she received both her BFA and MFA in Creative Writing at UBC, she now lives in Edmonton with her husband, playwright Kevin Kerr, and their two sons. Kerry: Marita, I think I’m beginning to change my mind. You see, I’ve been fascinated by narratives about motherhood since before I was a mother, and as I prepared to become one, I devoured the modern “ambivalent motherhood canon”.

But I’ve been reluctant to pursue such narratives myself. When I interview writers, I insist that their work is what’s important, and I avoid questions about writing and motherhood that would probably fascinate me as much. I worry that such questions would undermine the writers’ works, would undermine the individuals as artists, would undermine me as an interviewer and a reader. But I can’t shake a suspicion that these questions are important, that perhaps we just have to carve out a time and space for them. Or not. I’m not sure.

Did you feel any similar qualms as you embarked upon your Motherhood and Writing interviews?

Marita: When I first conceived of the Motherhood and Writing interviews, I had no qualms at all. I think that may have been because I really wasn’t aware of all the books written about motherhood and writing. I’m sure if I had dug a bit, I would have discovered them and not felt the need to start the interview series.

The interviews came from purely selfish place. I wanted content for my blog, but more importantly, I really needed to know how other writing mothers did it. My boys are twenty-two and a half months apart. When my second child was born, I panicked. I remember clearly breast feeding him while reading a biography of Margaret Laurence and having the terrifying flash that I would never write again. I knew I wasn’t as driven as Laurence was and couldn’t make the choices she had. My nascent career was over.

After my husband helped talk me down, I realized that of course my career wasn’t over. There were many, many writing mothers out there who were kind, loving, stable mothers. I wanted to talk to them simply to know how they did it. How does a mother balance all those things mothers do and make time to write. And I wanted to talk to women who were in various stages in their careers–from award winning to not yet published.

The project was supposed to be just for a year, but I’ve managed to draw it out longer, partly out of laziness and partly whenever I think it’s time to shut it down, I’ll get an email or a comment on the blog from some writing mother out there to thank me. It’s important, especially in those early difficult years, for those in the trenches to be reminded that they are not alone, that there are other women out there who are struggling, too. And, of course, that it will get better.

That said, recently I’ve begun to have qualms. Maybe it’s because I’m no longer in the trenches, or maybe because I’ve become sensitive that I might be contributing to the creation of a “motherhood ghetto”.

We would never ask a man how he manages to write while being a father, so why do we feel it’s relevant to ask a mother? Is it because there is an assumption that the woman is at home with the babies and that the man is not? And that if she isn’t, she should be? It’s insulting to both mothers and fathers. But I don’t know what I’d rather see–interviewers asking fathers what they ask mothers, or stop asking mothers what they don’t ask fathers.

So, yes, I am now quite conflicted. I hope that in the context of my interview series, the questions I ask aren’t insulting because that is the point of the interview. But I don’t think if I was interviewing a writer in another context, I would feel comfortable about asking about their relationship between writing and motherhood, unless the writer brought it up or it was clearly related to the writing.

Kerry: But yet, beyond domestic drudgery and “how does she do it?”, fascinating connections abound concerning art and motherhood. These interest me the most, and they’re questions that could serve to illuminate artists’ works and the experience of motherhood in general.

But there’s the matter of the ghetto, which you mentioned, and that, as Rachel Cusk mentioned in the introduction to A Life’s Work, that “motherhood is of no real interest to anyone except other mothers.” Why do you think this is?

Marita: I think there are a few reasons and they’re interconnected. The first that popped in my head is that it isn’t paid work, it’s part of the spectrum of “women’s work” (this label makes me want to scream, but I’m using it anyway). Also, because it seems anyone can get knocked up and therefore become parents (which anyone who has struggled with infertility knows how false this is), there is no understanding that parenting is a difficult job. I mean, how hard can it be, right? Turn on the t.v. and feed them and the job is done, right? Um, no.

It’s also invisible work. In public, unless you are a mother or you’re at a child/parent place (playground, school, etc.) you really only notice mothers when their children are in melt-down mode. Mothers are noticed when they are “failing”. I don’t know about you, but once I became a mother, I noticed how invisible I suddenly became.

But there is the inherent sexism of women’s work, too. In a patriarchal society, women’s work isn’t valued work. For mothers, the outcome is important–we want children to become obedient, hardworking adults–but how it’s done isn’t important. The idea of the loving mother is celebrated, but please keep that mechanics of that behind closed doors. We want to see smiling mothers and quiet children–not the day to day drudgery.

All these economic and feminist reasons I’ve been obsessing about since I became a mother, but this morning I woke up with might be the most basic reason: because it’s shop talk. Who likes going to a party and have to hear workmates talk about their jobs the whole night? Maybe it’s that simple with motherhood. People who aren’t mothers don’t care because they can’t relate, don’t want to relate. The politics and theories don’t interest them because they don’t affect them. (Although, I think the politics of motherhood does affect the wider society, however I’m sure the banking industry has an impact on my life, but I don’t really want to hear about either.) It seemed like such a revelation this morning, but now writing it down to you, it feels a little weak. What do you think?

Kerry: I actually love that idea, that it’s shop talk– it is! And it’s easier to think of motherhood being boring for that reason rather than motherhood itself being inherently boring. And yet, putting motherhood up/down there with dental hygienisthood and geography teacherhood isn’t quite right either, is it? Or perhaps it undermines what I’m most interested in about motherhood– how it changes how we understand the world, how we understand our bodies, other women, our own mothers. Issues of empathy, bonding.

I think that motherhood is mostly boring for a reason you mentioned– that it’s so ordinary. Everybody’s mother was a mother, and a lot of daughters will end up being one too, and quite a few of them even managed to go about it without waxing ad nauseum on the subject. Without having conversations like these.

Do you think it’s a phase, this obsession with motherhood? You’ve mentioned that you’ve moved away from it as your kids grow out of babydom. Was it a necessary phase? A useful phase? And how do we make it about more than navel-gazing (which so much online conversation about motherhood, I regret, never manages to do)?

Marita: On a personal level, I think it is a phase, at least at this level of intensity. I wonder if it is a product of our society, this need to analyse it so much? I can’t imagine mothers of our grandmothers’ generation dissecting it so much. Is it because we generally have children at a later age? We’re having less children? We’re not as physically (and perhaps emotionally?) as close to our families as generations past, so it’s more foreign to us? So many questions I don’t know how to answer.

For myself it was both necessary and useful. I was the first of my close girlfriends to have a baby and other than my small, immediate family, I have no relatives in North America. My husband had some friends with children, but I wasn’t in his life during their early years. Despite always knowing I would have a family, I had no idea what those early years of motherhood would be like. I became obsessed. I think that’s normal.

I learned so much about motherhood, about myself. I especially needed to see my position as both a writer and a mother reflected back at me. It’s almost silly now to think how desperate I felt, how much I needed to see that yes, I could be both a writer and a mother. The day-to-day life of writers and mothers can be terribly solitary. I needed to know that I wasn’t alone.

How do we get past navel-gazing? I don’t know. Partly we need it to be navel-gazing, because we need to see ourselves, our situations reflected back to us by others, and how can we do that if we don’t talk about ourselves?

Motherhood is incredibly transformational, especially for those of us lucky enough to have been able to conceive, carry, and birth our children. The physicality of pregnancy and birth is so intense, so raw and life-changing. Birth changes you. You battle through this profound visceral event, and on the other side of it, you have a new title, a new job: mother. It’s crazy. Of course we’re going to talk about it, analyse it, try to make sense of it.

I’m curious about your desire to take beyond the navel, that’s my impulse too, but I’m not sure what the forum should be. Are you specifically talking about the online world?

Kerry: Oh, I’m talking about the whole wide world, but online in particular. I think that’s what I liked about your motherhood and writing interviews– that they were looking at motherhood in the context of something bigger, and that was so interesting to me. Perhaps I also needed a reflection of mother/writers, to know it was possible.

Whereas the whole mommy blog circuit was just depressing, uninspiring. Once I’d grown accustomed to being overwhelmed by my crazy blown-apart new life, I didn’t so much want that experience affirmed, as some bloggers delight in doing. Maybe I am unusual in this, but I wanted to believe in the possibility of something better, something more. That I wasn’t limited to this entrenched idea of motherhood– of being forever harried, depressed and stretched to the point of exhaustion. I mean, of course it was nice to know I wasn’t alone in the hardships, but when life is really awful, how much do you really want it reflected back at you? And how far can that kind of reflection really take you?

If we’re talking beyond navels, I’ve been really inspired by the work being done through the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement (MIRCI, formerly the Association for Reseach on Mothering). Their book Talking Back to the Experts was a real tool of liberation for me as a new mother, and I also appreciated Mothering and Blogging: The Art of the Mommy Blog, which gave me such an appreciation for what blogs about motherhood have done in particular for marginalized or isolated mothers. These books had me understanding my own experience in a wider context, and also addressing issues of feminism and motherhood and how these ideas support and contradict one another. That motherhood was a job that required a great deal of thinking, learning and understanding. Worthy of an area of academic study, even– I liked that.

I wonder if the level of analysis and need for understanding you so astutely addressed is particular to artists– writers tell these stories over and over again, but would an architect fixate on the narrative quite so much? Does our artistry give us the means to engage with motherhood as we do, or do you think it happens to everyone?

Marita: Thank you, I’m glad you liked the interviews! I think you nailed how we can take the discussion of motherhood beyond the minutia–by talking about it in relationship to something else. Perhaps that is why we talk about it so much now. Our mothers’ generation was fighting for our rights to be anything we wanted to be, and now, our generation is figuring out how to negotiate our place within so much choice and what that all means.

As a huge, sweeping generalization, there seems to be two types of mommyblogs. The negative, complaining ones you mentioned and then the ones on the other end of the spectrum, where everything is perfect and idealized. No chaos, all domestic bliss. It’s hard to be in that place, too. Neither options feel honest or a reflection of my reality. But I must to admit that I still read a couple regularly, and one of them is the “perfect life” kind. (However, if she didn’t post every day, I probably would stop that one, too.) I can’t read the negative ones at all.

Your last question is a hard one. My hunch is that most mothers want to reflect on motherhood, at least early on and I think that’s why mommyblogs are so popular. That said, artists have the creative vocabulary to fixate, which many people do not, but more importantly, it’s our job to fixate. A new mother who returns to work at her architecture/accounting/law firm has other work she’s paid to do, but as artists, one of our jobs is to obsess. So many artist-mothers that I know try to work from home at the same time as trying to be a SAHM. Both are full time jobs, so it makes sense to me that this obsessing ends up being reflected in our work to some degree. Writers specifically create narrative, so of course we’re going to examine and dissect how this new character is changing our personal narrative arc.

I believe that every experience we have somehow influences our work. I haven’t read Emma Donoghue’s Room yet, but my hunch is that it would have been a very different book if she wasn’t a mother. You’ve read it. What do you think? And do you think you can tell if an artist is a mother? Would you want to?

Kerry: I think an artist can imagine her way into motherhood, and I say this with assurance because I’ve read Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin. I remember reading the novel The Almost Archer Sisters by Lisa Gabriele too, and being stunned to discover that Gabriele wasn’t a mother– it’s a funny, popular novel, but her depiction of mothering a disabled child is stunning. I asked Alison Pick if she’d made changes to how she wrote about parenthood in her novel Far To Go after her daughter was born, and she said she’d pretty much got it right the first time (and she did).

What was remarkable about Room to me was not how “right” Donoghue got my experience, but that she’d actually managed to articulate aspects of my experience I hadn’t before been conscious of– which is really incredible. I’m at home all day alone with Harriet, and I remember as I was reading that everything I said and did was taking on a new resonance. I had never realized (perhaps because Harriet is still so young) how much a mother constructs her child’s universe in the various real-world Rooms in which they find themselves– the womb, the empty house alone all day.

I think if Donoghue hadn’t been a mother though, Room would have had a different kind of emphasis. I recently read James Woods’ review of the novel in the LRB, and he wrote about its lightness, its readability, the cutesy focus on Jack– and how the actual story that inspired the novel would not have such a rosy tinge. Because of her focus on the mother-child bond, Donoghue was able side-step a horror story, the fact that an actual mother probably would not construct such a fair and happy world for her child, would have neither the tools nor the capacity to do so. Room is a fairy-tale, really. Perhaps as a mother Donoghue was unable to look the real situation in the face (and I can’t blame her). Her story is a hypothetical one rather than a particular one, and there is safety in that.

And I must say that you’ve just answered my question, Marita! Well done. You ask, “Can you tell if an artist is a mother?” and I think, perhaps, one can’t. (Though sometimes, with bad artists, you can tell when they’re not a mother cough cough Christos Tsiolkas). Which means that my longing to ask or not to ask questions to artists about motherhood is kind of beside the point of the art. Has more to do with my own life and my own interests at the moment than art itself. (Ah, sweet navel, nice to gaze at you some more…) Which doesn’t mean these questions don’t matter, and can’t be incredibly useful/interesting in some respects. But perhaps my aversion to dwelling upon them comes from a rational place?

I think, Marita, that we’ve come full circle, and in a satisfying way. Do you think so? Can you tell if an artist is a mother?

Marita: Yay! I’m glad I helped you find your answer. I agree, I don’t think you can tell if an artist is a mother, and one wouldn’t want to. There are things that only some mothers can know, like what let-down feels like, or when your water breaks, but those details are so small that they are insignificant when it comes to the creation of art.

Someone once told me to not write what you know, but write what you want to know. This seems rather relevant to this conversation. I’m more drawn to writing about certain subjects and themes at the moment (my polygamy project) because of motherhood, but I know I won’t only write about those for the rest of my life. As artists, it’s what interests us in the moment, and for some it is motherhood.

I do think, however, that we still need to have conversations amongst writing/artist mothers, even if it is simply to compare navels and say, yes, that’s normal too.

October 8, 2010

The world in fiction

Last night I was part of a discussion with a group of women whose collective brilliance could light up the universe, and we were talking about using the real world in our writing, fiction or non-fiction. (We were also drinking champagne, eating cake, and delicious cheese, but that is another story.) Everybody had such fascinating input, about the ethics of using other people’s stories, about writing historical fiction or speculative fiction, and using the details but not conspicuously. About writing memoir, and something about fiction being the truth told twice. And then someone brought up Carol Shields’ Small Ceremonies, which was so perfect, being about this very topic, and also because for about two days, I’ve been dying for somebody to talk about Small Ceremonies with.

Anyway, I thought about the one story I’d ever done substantial research for, which was set in 1976 when the CN Tower first opened. I have long been fascinated by my impression of the CN Tower as a permanent fixture on the horizon, as old as the universe, or at least as old as the TD Tower, but then to realize that it’s only three years older than I am (but then, don’t we all envision ourselves too as well as permanent fixtures on some horizon, old as the universe?). That, not entirely literally, Torontonians went to bed one morning and woke up to a tower in the sky.

So that was what my story was about, and I spoke to people who remembered the tower’s construction, and read a 1970s’ Toronto guidebook, and read every archived newspaper article I could find on the subject. I went through the CHUM charts to find out what was playing on the radio (an aside: these were all available online until about two years ago, when CHUM was bought by CTV). I read Toronto fiction from that time, and spent a lot of time thinking about the view from our friends’ high rise apartment at Yonge and St. Clair. We were also so poor at this point in time that a research trip up the tower itself required budgeting for weeks, but we did it on one cold February day in 2006. I’d brought a falling apart book about Toronto from the library so we could compare the views.

Geographic or historical detail, as someone noted last night, can function as a scaffold. We seemed to also conclude that broad strokes work best in convincing historical fiction, and it reminded of what Alison Pick said in our interview: that the essential goal of historical fiction is that its details be grounded in time and place, but the feel and its characters be entirely contemporary. That a scaffold has to come down once the building is completed. That a writer has to ground herself in the details of time and place, and then forget it in order to get the story written. That the detail of where a story takes place, or what is playing on the car radio, or what kind of car it is– that none of this is important, unless it functions in the story at a deeper, symbolic or metaphoric level. And in terms of place, I thought of how Claudia Dey did this so well with Parkdale in Stunt, and Elise Moser with Montreal in Because I Have Loved and Hidden It. The broad strokes with which Hilary Mantel evoked the Tudors inWolf Hall. How with the best novels we’ve read in our book club (Shirley Jackson, Muriel Spark), we’ve remarked that these stories are ageless, could have taken place in any time. And perhaps a similar spirit needs to be striven for in historical fiction too, in any fiction. Spirit can’t come from detail for the sake of detail– everything has to mean something. That the song on the car radio is a kind of cheating, and it shows.

My CN Tower story was a mess, a catalogue of facts and coordinates. I haven’t tried to set anything in the past since, but I’m thinking about it now, as a kind of challenge. A detail-less historical short story– I wonder. And I will keep in mind a point somebody made last night– that people themselves are the centre of our stories, and people themselves don’t change that much. Reflecting this morning upon this, I remembered how my CN Tower view was nearly identical to the pictures in my battered book. Perhaps this means something more than itself, and I’ll try to keep it in mind.