October 18, 2021

When I’m shining everybody gonna shine

I don’t know if I smiled any wider last week than I did at the news that my friends’ new novel (The Holiday Swap, by Maggie Knox!) had made the Toronto Star bestseller list, and with this news came such overwhelming gratitude that other people’s good fortune could be fuel for my fire. And I’m writing this not to be smug, but just because I’m glad, and I’m still not 100% sure how I got to this place (though I wrote about it in a post a few years ago called “How to Get Over Literary Envy”).

I remember many years ago feeling so much more desperate, perceiving other people’s wins as a kind of violation, and no doubt some of the change has come about as I’ve grown older and settled into myself, achieving creative goals that I’m proud of (though I have yet to land on a bestseller list). This process too has taught me how much of success is usually a combination of painstaking work and glorious fluke anyway, which makes it harder to resent it when it lands on somebody else’s doorstep.

Though I will confess that there still exist more than a few people whose success makes me roll my eyes and grit my teeth—but these are mostly petty grievances, and the people in question are largely unknown to me (which, obviously, doesn’t mean that I’m barred from finding them annoying).

The people who matter to me though: I want them to win, and not just because of how I seem to win when they do—but yeah, that part also feels pretty good too.

October 13, 2021

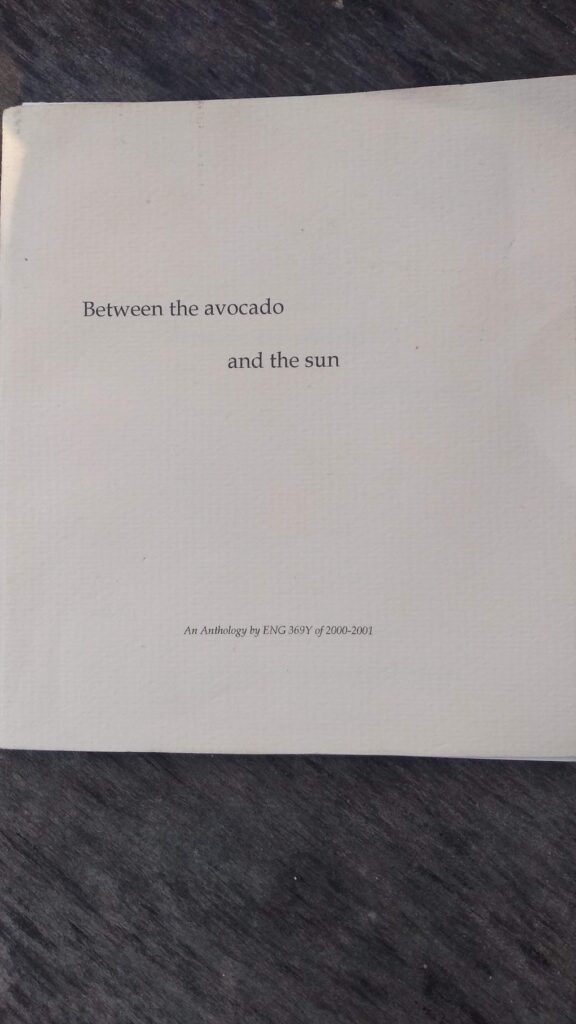

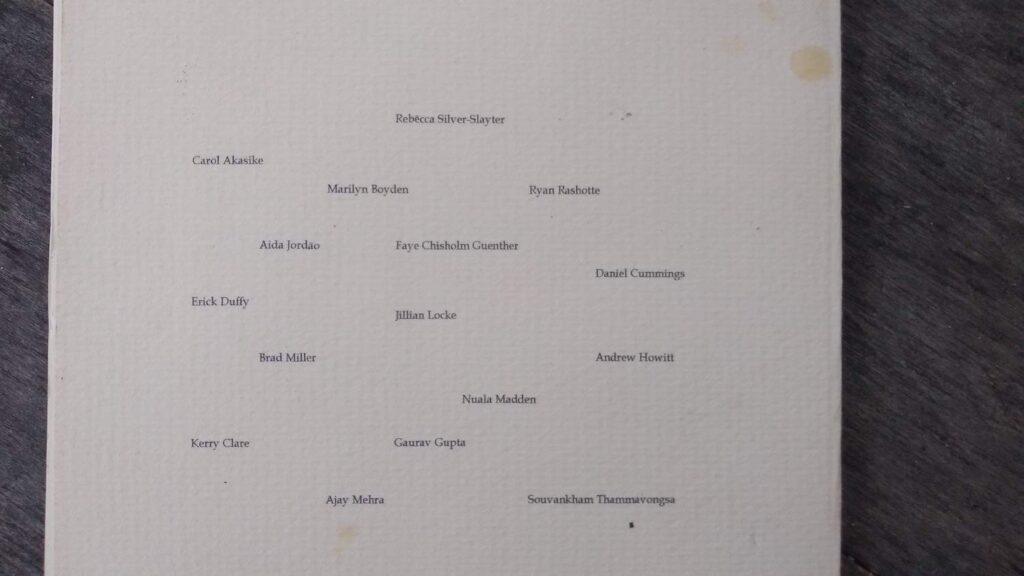

Class Reunion: ENG 369Y 20 Years Later

During my third year of undergraduate studies, from 2000-2001, I was part of ENG 369Y, a creative writing workshop led by Dr. Lorna Goodison through the Department of English at the University of Toronto.

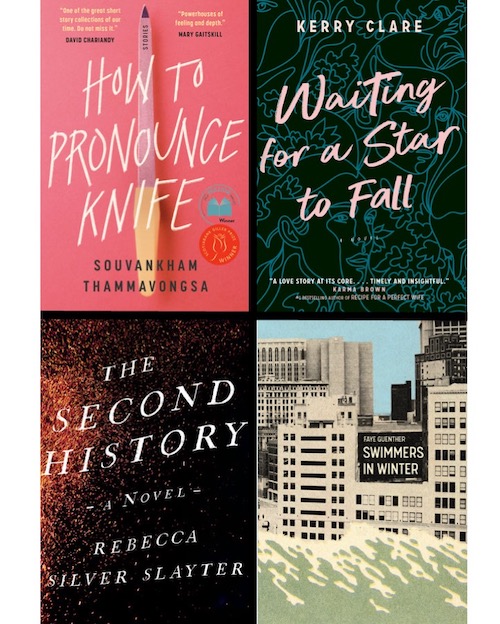

For so many reasons, many illuminated below, this class would be an unforgettable experience, though it seemed especially remarkable when—two decades later—four of us from the class would all be publishing books within the same year and a bit.

- Souvankham Thammavongsa’s How to Pronounce Knife was published in April 2020, and it was awarded the Scotiabank Giller Prize that year, as well as the 2021 Trillium Book Award, among other accolades.

- Faye Guenther’s Swimmers in Winter came out in August 2020, and it has been a finalist for both the Toronto Book Award and the 2021 ReLit Award.

- My book, Waiting for a Star to Fall, arrived in October 2020, and the Montreal Gazette called it, “Subtly complex […a] romantic drama tailor-made for the #Metoo age.”

- And Rebecca Silver Slayter’s The Second History found its way into the world this summer, with no less than Lisa Moore writing that it’s “one of the most honest renderings of romantic love I’ve ever read. [A] truly mesmeric story, tender, unflinching, quakingly good.”

To me, the serendipitous occasion of our new releases after all this time seemed like an splendid opportunity for us to reconnect and reflect on our time together, as well as so much that we’ve learned about writing in all the years since then, and so the four of us shared our thoughts and ideas via email.

tell us about 20 years in the writing life, about the trajectory of your writing life since our class together in 2000.

Kerry Clare: I don’t think I had a focussed relationship to writing at all in the first ten years after our class together, even as I completed a MA in Creative Writing at the University of Toronto from 2005-2007. There is a line in Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life that I may have misremembered, but it’s about a superficial idea of writer-dom being analogous to one admiring the way one looks in a particular hat, and I always thought she was talking about me, which was mortifying.

When I finished graduate school, I worked for two years reading financial documents all day long, which was not fun, but gave me stability and a salary, though little in the way of creative inspiration. It also gave me parental leave benefits, which I used when I had my first child in 2009, and becoming a parent really seemed to up the stakes for me writing-wise. I became invested in the world in a more meaningful way, and therefore had more to write about. My first big success in writing was an essay about new motherhood I published in 2011, and this led to my first book, the essay anthology The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, which I edited and was published in 2014.

At this point, I wasn’t sure that writing fiction was going to be my destiny, and was even making peace with that (throughout this entire period, I’ve been blogging, which has been a creative lifeline), but then something clicked shortly after my second child was born and I finally figured out how plot works. My first novel, Mitzi Bytes, was published in 2017, and I’ve been writing them ever since, and though I am constantly terrified that one day I won’t know how to do it anymore, it seems to keep happening.

Souvankham Thammavongsa: I am not a very good example of a writing life because my trajectory isn’t a simple one and it is not for everyone. I don’t think anyone would want it. I worked for fifteen years in the research department of an investment advice publisher, I counted bags of cash five levels below the basement, I prepared taxes. This work helped me write what I want and it didn’t take away my desire to write. I still have that from 2000, this desire to write, but it wasn’t anything someone taught me.

Faye Guenther: I stayed at the University of Toronto to do undergraduate and graduate degrees in English. Then I went to York University and did a PhD in English. While I was a student during those years, the jobs I had to support myself weren’t related to writing, but they showed me things about the world and this is useful to a writer. I’ve found that no matter what you do, the key is to make the time to write. My writing life has also been shaped by who I’ve met along the way, including fellow writers. In 2017, I published a chapbook of poems and short fiction, Flood Lands, with Junction Books. In 2020, I published a collection of short fiction, Swimmers in Winter, with Invisible Publishing.

That is probably most of what I’ve learned in these two decades. How to take in all the advice, all that you’ve learned from other things you wrote, from things you read, from other writers, and then listen very hard for the tiny sound of this book calling for what it needs from you.

Rebecca Silver Slayter

Rebecca Silver Slayter: I decided to stop writing not long after that workshop. I think, to reverse what Souvankham said, I worried my desire to write might be something someone had taught me. That I had lost track of why I wanted to write at all.

So I stopped for a year. Or two. Or three? It felt like forever because I was 20-something and everything was forever.

And meantime I decided to make my life and work writing-adjacent. I interned at Quill & Quire and The Walrus. I worked for a startup children’s publisher. I did odd jobs to complete the financial math, yardwork and errands. Eventually I was hired for my dream job, working as managing editor for Brick literary journal.

Sometime in the midst of that, I met my husband, and told him, proudly, how I had made the tough, mature decision to give up writing, and he listened and nodded and then said, I know you are a writer, with such certainty that I didn’t know how to doubt him and I began writing again. And I found to my great joy what I had been missing in those earlier writing years; a desire to write that easily overtook the desire to be a writer.

I did graduate studies in Montreal, where I wrote the first draft of my first novel, In the Land of Birdfishes. When I graduated, I returned to Nova Scotia, and bought a house for a song in Cape Breton, which I will be renovating for the rest of my earthly days.

This is for me a very good place to write, near the ocean and the highlands, in a community where music and storytelling are woven into everyone’s daily life. Here I published my first book and then wrote and rewrote and rewrote my second book, which was just released this summer: The Second History. It took me eight years from first draft till now, mostly because I tried to write it faster than I’m able to. It turns out I’m a writer who needs to take my time…

That is probably most of what I’ve learned in these two decades. How to take in all the advice, all that you’ve learned from other things you wrote, from things you read, from other writers, and then listen very hard for the tiny sound of this book calling for what it needs from you.

what was the best thing the writer you were in our classroom had going for them? And what writing advice would you give that previous incarnation of you? (Though would you even have taken it?)

ST: My intuition. I listened to everyone, and knew when not to. This taught me how to pick through edits. When we see edits, sometimes it’s about the person and their life experience and it doesn’t mean they are right or know but you have to be generous and allow them to have their thoughts.

I wouldn’t give myself any advice. I think advice can be a disservice to a writer. There’s a lot I didn’t know and I want myself to not know and to live in that not-knowing in order to know it. I want myself to encounter and work through those difficult and lonely moments. I don’t want anyone to hold my hand or do me any favours or make it easier or easy. I like the difficult, and I want to continue with that difficulty.

RSS: One of my clearest memories of that workshop was of Professor Goodison saying, as we discussed one of my poems, “You come from preachers, right?”

I was tongue-tied with confusion. “What?”

“Your people, they’re preachers, right?”

I had absolutely no idea what she meant. “No….” I stammered.

“Then why are you preaching at me?” she asked.

Oof. Caught. I was constantly preaching. Trying to find a much-too-simple way of understanding much-too-large things. I had a weakness for sentences that began like “Love was…”

I think somewhere in this is both my weakness and strength as a writer (probably as a human too). It is writing-in-bad-faith to just polish up pretty turns of phrase that sound truish. To go around making tidy summaries of untidy things. But… I think if I mine deeper I can find underneath that impulse what drives me to writing still, and to reading itself… The sense that there is some luminous other way of noticing the world that will make it brighter, stranger, more visible. That certain words can be incantatory, a pathway to looking again and seeing more.

I have two small children, and have found it astonishing to witness language dawn within a person who formerly had none. How each child altered a bit around the language they used. How they learned what it was then to be nervous, even tired, even thirsty. How what began as the ragged, indeterminate longing of a baby’s howl became so clear, so precise, so unmysterious. And I miss a bit the mystery. The wonder of watching a peer being who doesn’t know what yesterday is. But I think there’s another way that language can give us back what experience has made ordinary. And I think that’s what I was searching for twenty years ago and search for still, but with a few degrees more purpose. And a lot more joy.

So I would maybe advise myself something like this: First, don’t write any more poetry. You are very bad at it. And for a time, don’t write at all. Wait until the desire to write is something you have to resist. Wait until it wells up in you. And then go find the joy of writing words that make you look again, more deeply.

I wouldn’t give myself any advice. I think advice can be a disservice to a writer. There’s a lot I didn’t know and I want myself to not know and to live in that not-knowing in order to know it.

Souvankham Thammavongsa

FG: I remember being openhearted and creative. The writing advice I would give my earlier self is to be bolder. I think when boldness is combined with a practice of being open with yourself and to the world, there is a sharpening of creative focus that can happen and a strengthening of creative perception, no matter what challenges life brings.

KC: The writer I was in our classroom had no idea how much she didn’t know, and far more confidence that she deserved to have, and I’m so happy she did because being 21 is hard enough. I was not a serious person or a serious writer AT ALL. (I remember that Souvankham appeared to be both, and it was such a powerful example for me, though I think I was still too young to fully appreciate it.)

What a tremendous opportunity to develop my skills that class should have been!! But I did not work all that hard, honestly, too busy checking out my look in the hat, remember? I mainly wrote poetry because you could finish a piece in a few minutes. This did not mean my poetry was good, however, although I think sometimes some of it was.

If I could give that writer I was any advice it would be to write something REAL, instead of something you think sounds like something that could be real. (And find writers you love, instead of reading all the writers you’re supposed to love.)

For the record: I would not have listened.

what roles have literary journals and small presses played in your writing career?

RSS: I know literary journals and small presses better as a worker than as a writer. But I am shaped permanently by my years at Brick literary journal, and by the trips I made then, twice a year, to Coach House Press, where the journal was designed at that time.

The Coach House basement was a kind of church I visited like a disciple of those beautiful machines for cutting pages and laying type … and of the people who made them run and knew the stories of an older Toronto and the mesmerizing adventures then had by not-yet-famous writers. In a way that is both corny and essentially true to me, that is what I feel a tiny part of when I write: all the people in all those tiny offices and studios and nooks making small-press books and magazines; their labours of love, their care and bravery, those parallel arts of ink and paper, alongside those of prose and plot.

They taught me what was foundational to writing; the courage and the care of the work. And the kinds of community it can build.

FG: Reading literary magazines gave me an awareness of community. They were the first space where I was published, and I know this is true for many writers. Smaller presses often foster innovative and ground-breaking work. They frequently publish voices and stories that historically have been marginalized. I think smaller presses are important for energizing and sustaining a vibrant creative culture.

My first piece of published fiction was in The New Quarterly in 2007. I will never forget the joy of receiving that acceptance

Kerry Clare

KC: My first piece of published fiction was in The New Quarterly in 2007. I will never forget the joy of receiving that acceptance, especially in the wake of the novel I’d written for my Masters thesis that went nowhere (because it was boring!) because I was really feeling kind of discouraged, and then this message from the universe arrived suggesting maybe I should keep going after all. In the next few years, I would publish pieces in TNQ and other journals, and the high of an submission being accepted has never diminished for me. And then Goose Lane Editions, a remarkable Canadian indie press with an impressive history, published The M Word, and did the book such justice. Without literary journals and small presses, I’d be nowhere.

ST: Literary journals teach you things a writing class or editor or a dear friend and family cannot. They don’t love you and are not beholden in any way. They teach you about rejection—what that feels like, what to do with it. They are often the first place where we get to see ourselves in print. It’s important for a writer to understand the difference between seeing yourself in print and publishing a book. They are not the same.

what are your favourite memories of our class?

ST: I remember the talent and fun. There were so many writers in that class who are more talented, more ambitious, more interesting…but they aren’t here, or with books. They became lawyers and engineers and professors. I always keep that in mind. Having a book doesn’t mean I am good.

KC: I have so many memories! I don’t know if we were particularly interesting as a group, or if it was the work of Professor Lorna Goodison in creating community, or just the particular mix of experience and personalities in our class, but I felt very connected to everyone. I think we were a well written cast of characters.

I remember Souvankham on the very first day, and how she impressed me so much with her sense of herself. I remember we had to write a poem inspired by postcards, and mine had a field of sunflowers and said, “Welcome to Michigan,” and I wrote a poem with the line, “I won’t forget the motor city.” I remember REDACTED who wrote a poem with the line, “Let’s make love in the astral plane,” and I was seriously impressed by how sophisticated he seemed. And someone else who wrote a poem about someone sucking on her toes while listening to Robbie Robertson sing “Somewhere down the crazy river.” Everyone seemed to be having a lot more sex than me. (One could not have been having less sex than me.)

I remember Faye seemed especially interesting, partly because she seemed kind of badass with a shaved head, and we always sat in opposite corners of the room. And how I was in love with the name “Rebecca Silver Slayter,” which belonged to the woman who often sat in the same corner as me and whose work I felt very drawn to.

I think it’s kind of wonderful that in addition to the four of us, plenty of others in that group have gone on to very interesting careers in academic, television writing, and more.

One of my memories of the class was discovering what a literary reading could be—the ways prose and poetry can be shared beyond their existence as words on a page and become something like music in a public space.

Faye Guenther

FG: I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to learn from our teacher Dr. Lorna Goodison. One of my memories of the class was discovering what a literary reading could be—the ways prose and poetry can be shared beyond their existence as words on a page and become something like music in a public space.

RSS: This sounds like very cheap, opportunistic flattery, but honestly, though I remember well many of the talented, interesting writers in the class and their poems and stories, what I remember most clearly is the three of you.

I remember how beautifully Souvankham’s work was always laid out on the page in lovely, tiny type—the form so perfectly echoing the work itself, the grace and economy and polish of her words; how her work seemed always already complete, and I was stumped on how to write any feedback that didn’t just feel like tampering.

How Kerry’s writing was funny and powerful at the same time, and I hadn’t even known that was possible. How she seemed so at home both on the page and in the classroom, warm and open and at ease in a way that awed me. I remember Faye’s compassion for her characters, their rich interiority. How reading her stories felt like someone whispering in your ear, that intimate.

My strongest memory of the class was the first one. When we went around the room and each offered up our names.

Souvankham was near the end, seated at the table perpendicular to the one where Professor Goodison sat.

After she said her name, Professor Goodison asked, “So what do you want to be called?”

I was caught off guard by the question, but Souvankham answered clearly and immediately. Without blinking or skipping a beat, she said: “I want to be called a writer.”

Professor Goodison looked at her and Souvankham looked back. Then she said, “I’m going to call you Sou.”

And I was as astonished as if Souvankham had wafted out of her seat and up into the air between us. I was at that time so uncertain, so full of twenty-one-year-old desires to be interesting, to be brave, to be invisible and/or famous. I would have probably told Professor Goodison she could call me whatever she wanted. Or tried to guess what she might prefer me to be named.

Year by year over these last twenty, I get a little closer to what Souvankham already had then. That certainty. That clarity of purpose and identity as a writer that struck me silent when I was twenty-one.

April 30, 2021

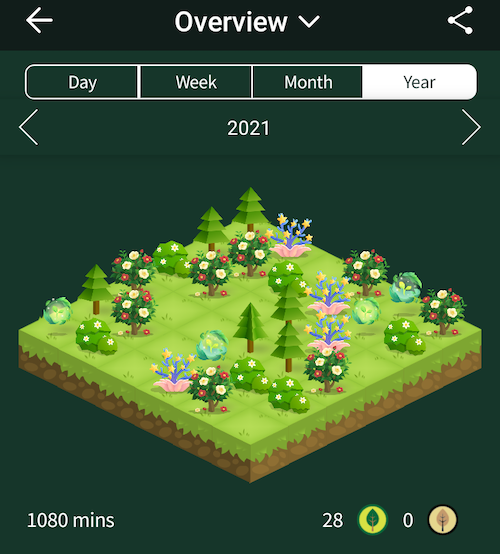

The Forest App

Everybody in my household is obsessed with video games, except for me, who spends weekend mornings reading the paper while everybody else is intent on the Switch, and sometimes I feel a bit left out of the narrative, but mostly I don’t care. I am gad that video games are something my husband gets to share with our children, and I am glad that there’s an adult who’s paying attention to this part of our children’s lives, but video games just don’t factor into my framework at all…except for the one instance in which they really do!

I learned about The Forest App two years ago from an article about reducing cell phone addiction. I’ve used social media blockers on my laptop and phone for years, which is how I manage to write anything that isn’t a pithy instagram story, but the Forest App was kind of a cool twist on the idea of these blockers, generative instead of restrictive. I set a time limit on my phone and if my phone stays undisturbed during that period, I grow a tree in my forest. If I use my phone, the tree dies. And reader: I’ve never ever killed a virtual tree. It would break my heart to kill a virtual tree.

I even have a vague suspicion that I’d have to go out of my way to kill a virtual tree—a couple of times I’ve picked up my phone to check an email and my tree has kept growing anyway, so maybe it’s just the apps or clicking on them. I don’t even know. I don’t want to know. I love that this app that’s only vaguely restrictive and may not even be restrictive at all helps me make good choices for focus even when I could be making different ones. Which is much more meaningful to me than a lock and chains.

A few weeks ago, I finally purchased the pro version of the Forest App, partly because I’m trying to pay for the online things I value, but also because I realized this could make the trees in my forest much more interesting and diverse. Tragically, however, this process deleted the substantial forest I’d been growing over the past year and more, but what can you do…but luckily I was able to start again, and with a camellia tree to boot. As part of their Earth Day challenge, I was able to unlock the luminie plant. This week, I actually increased by focus time from 45 minutes to an hour because I realized I get TWO trees when I do this (and yes, I get extra work done too).

As I grow my forest (while focusing on the work I want to do) I acquire points. I can use these points to unlock more trees, which is how I recently got the camellia. I need 2000 points to plant a plum blossom tree or a weeping willow. And I’ve got my eye on the apple tree and the maple tree (with orange leaves, and a park bench underneath!), and as my forest grows, I’m ridiculously proud of it, beyond my pride at what it represents in terms of attention and commitment to my writing…and everyone I live with is very kind and encouraging and pretends to be interested in my virtual trees.

And of course they are! Because this is my video game! Like Animal Crossing for boring people (or so I assume—I am too boring to know). And what with my virtual landscape and acquired points, what is this whole business but a video game after all. But one that is not remotely a waste of my time. Instead, it’s one that makes the best of it.

Even better? I’m not going to be unlocking any new virtual trees anytime soon, and do you want to know why? Because I’m saving my points. I’m currently at 393 after that camellia tree cleared me out but if I focus hard and work intently, I can earn 2500, at which I can use the points to plant a real tree! The Forest App is involved in the Trees for the Future program in Sub Saharan Africa. I can’t think of better motivation to get down to work.

September 25, 2020

How to Be a Champion, and Not a Sycophant

Some of my most important mentors have been the people who said no to me, the people who couldn’t accommodate my request, who didn’t want to help, who had better things to do than answer my email. From these people, I have learned that I too can set my own boundaries and limits, that none of us are required to be everything to everyone.

And so similarly was I impressed last spring when I approached a fellow author-friend for a blurb for my forthcoming novel, and she responded with a caveat—she would agree to read my book, but not necessarily to endorse it. Because how could she know if she hadn’t read it yet, and as a person who aspires for everything to mean what it means, this was a particularly powerful moment.

This story has a happy ending too, because this person really liked my book. And how much more her endorsement meant to me because it wasn’t granted automatically, because it meant something. But even if she hadn’t endorsed it, I would have admired that too. A sign that honesty and integrity are not as rare as one might think. And yes, my ego would have taken a bit of a bruising, but every public-facing person benefits from such an exercise from time to time.

Last week I wrote about the importance of making space for promoting books and reading, but this doesn’t require one to have to love everything. “The standards we raise and the judgments we pass…” Virginia Woolf refers to in “How Should One Read a Book,” and those standards and judgments are important. Not because they are the law, because they aren’t, and different readers and critics will have different standards and judgments, which is just the way it should be (and this is the great thing about making space—there can be enough of it to go around).

If you are making space and not adhering to your standards and judgments—raving about books you thought were terrible, blurbing books you’ve never read, recommending titles about which your take was mostly “meh,” holding your nose to post about a title your favourite publicist has sent you which is not your cup of tea, writing about a book that was rubbish but the author is super nice—then the space you are creating is not going to be very meaningful. And sometimes these kinds of situations are difficult to avoid, particularly if you are new to a community or less sure of your taste or less confident as a critic. But I would advise you to find yourself in these situations as little as possible to preserve your own literary reputation, your sense of self, and on behalf of the cause of better books, which is a cause we all can believe in.

Here’s how you can do it.

- If you can’t say no outright to review/blurb requests (it takes courage to be that bold) then you can make excuses. A lack of time is something nobody is going to argue with. Be vague. Don’t reply to emails. They’ll get the point. (There are people who will claim I am being unfair here, and that you owe it to authors to be honest and upfront. I have tried this. It has never gone well, and I will never do it again.)

- Build your wheelhouse. Most historical fiction, books about young men coming of age, novels with child narrators and fiction about philosophers I’ve never heard of are outside mine, which makes it easy for me to ignore these books without compunction.

- If that author on Instagram is super nice (even if she is me, although I am not that nice) and her book just didn’t jive with you, you don’t need to post about it. Even if she put it in her mailbox with her own two hands. The favour you did her was trying out the book at all. It’s not your fault if it didn’t work. And perhaps you can write a critical post that highlights the book’s redeeming features, but if none of those features can be found, just let it go.

- Be as brave as my friend and don’t agree to blurb a book you haven’t read yet. If you do agree to blurb a book that turns out to be terrible, fail to meet the deadline.

- Understand that a book may not be to your taste, but someone else might enjoy it. And that is terrific. Because you got to be honest with yourself and your audience and the book still got love. There is enough to go around without you bending over backwards.

- Know that it is not your job to take care of everybody

- And understand that your word is only ever going to mean anything if you mean the things you say. Your platforms matter. Use them wisely, smartly, and don’t water them down. And yes, we could be all throwing up our hands about declining ways to get the word out about books (and we do! And we are!) but that makes it all the more important to preserve the integrity in the places/platforms that are still available.

September 18, 2020

How to Do Self-Promotion

“There is nothing wrong with self-promotion!” someone tweeted at me a few weeks ago, an attempt at encouragement that demonstrated that they don’t know me very well, because clearly, I already know this . If I could afford to buy billboards for my selfies, I probably would. I really do hope that you will pre-order my new book (coming October 27 from Doubleday Canada!), is what I’m saying, but also that all self-promotion is not good self-promotion. There is a certain kind of grace required.

This all started because I have the best part time job ever, and I work with the best people , who fill my life with goodness and have been so supportive of my work for the past nearly-ten years. And my job involves getting excited about Canadian books, which is the greatest pleasure, and comes pretty naturally to me. But I am careful not to use this particular platform to promote my own work. I have other platforms after all, and it would be more than a little gauche. For me to include my book on the site’s Fiction Preview, for example, a project I care very much about and work hard on compiling.

So I didn’t, and my friend/colleague Kiley didn’t notice (it was a very busy summer!) until my book ended up on the Toronto Star and CBC Books’ Fall Previews the other weekend. And then she tweeted from the 49thShelf account about my forthcoming book, and how I hadn’t included it on our list. I replied that it’s kind of tacky to put your own book on your own list, and that it is to be hoped instead that somebody else might be anticipating my book, someone who isn’t even me—a gamble that had paid off (phew!) because at least two media outlets were.

Um, and yes, props to my fantastic publicist at PRH, of course. I suppose it’s easier to be kind of laissez faire when you have such people in your corner. It’s not all karma, is what I’m saying. But some of it actually is.

And what I mean by this is that the best way I know to do self-promotion is to create the space, instead of focusing on my own book specifically. This is a long-term goal, of course. You don’t start this six weeks before your pub date. Instead, you use whatever platforms you have—both digitally and in the actual world—with the intention of creating meaningful conversation, in my case about books and reading in general. Supporting a culture of literature in the places I hang out in, connecting with others who do so. And this culture matters. As Virginia Woolf wrote 95 years ago of the importance of readers in her essay “How Should One Read a Book?”—“The standards we raise and the judgments we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work.”

So how to create this space? Maybe you have a book blog. Maybe you interview writers on Youtube. Maybe you started an online literary magazine. Maybe you post about the books you love on Facebook. Maybe you run a reading series. Maybe you post photos of your library haul on Instagram. Maybe you talk about books exuberantly to the people you encounter in your everyday life. Maybe you support independent bookstores/ Maybe you read conspicuously in public. Maybe you do things to support the spaces that were created by other people, attending literary events, buying books, reading book reviews. Maybe you listen to books podcasts, and then tell other people about the books podcasts. Maybe you write Goodreads reviews, and leave reviews on Amazon—although even typing this makes me nauseous because nothing associated with Amazon is good for anybody, so if these are your tactics, perhaps think of one more.

The point of this space you’re creating is still not to promote your own book. Forget about your own book, for now. This is not about you. The point of this space you’re creating is to make more room in the world for books and readers, and even just a little tiny bit more space means something significant. And you’re benefiting from this space, because you are a reader, and you live in the world, and you’ve done your part to make the world a little closer to the kind of world you want to see—where books and reading matter.

And then, yes, because there is more space, there will also be more room for you and your book. Because you’re steeped in the atmosphere of books and reading, it will not seem so awkward to make your own book a part of the conversation. And because you’ve cultivated connections and built relationships, you won’t be the only person talking about your book either, which is the kind of promotion that really matters, which is really just living the dream.

But first, you have to make that space. Talk about and share the books you really love. You are not in competition with other writers—a world where people love and value books is good for everyone, even if the books they’re loving and valuing aren’t yours. There is room enough for everyone, especially if you’re making space. The success of any writer can be a success for all writers.

Of course, feel free to take all this with a grain of salt because modest success is all I’ve ever known anyway. I’m a blogger after all, inherently on the margins. But still.

When you hear someone asking for a book recommendation, resist the urge to suggest your own book (because of course you’re going to suggest your own book). Not because there is anything wrong with self-promotion, but because it’s just too easy and obvious to create any meaningful connection. You really do have to go the long way around, but it’s worth it. Because it’s real.

September 6, 2019

Book News: Waiting for a Star to Fall

It is with more joy than you can imagine that I write you with the news that my second novel, Waiting For a Star to Fall, will be published next summer in Canada and the US by Doubleday Canada.

For fans of Joanne Ramos and Zoe Whittall, and Emily Giffin, a sensationally gripping and resonant new novel about a young woman caught in the midst of a political scandal.

When political superstar Derek Murdoch is brought down by decade-old allegations of sexual misconduct, his on-again/off-again girlfriend Brooke is left to process the situation. Derek’s reputation is being dragged through the mud because of his propensity for dating much-younger women who work for him–but Brooke knows the situation is more complicated than that. Never mind that she was once his young employee too. . . .

As the public makes up its mind about Derek, Brooke is forced to re-examine the story of her relationship with him–a position made even more complicated by the fact that she and Derek are now estranged after a heartbreaking betrayal. She’s shared the reason of their breakup with no one–but now she fears it may rise to the surface.

Torn from the headlines, Waiting for a Star to Fall is a novel for the #MeToo era, an absorbing story that examines the complex dynamics of politics–and sexual politics–and questions the stories we tell about people in the public eye, and the myth-making of men.

Two years ago (or thereabouts), my friend May bought me a bought that said NOVELIST on it, a title I’d always felt strange assuming, because it seemed kind of presumptuous. even if I had just published my first novel. (Maybe it was all just a fluke?)

I’ve always been a bit wary of this idea that it matters what you call yourself at all, because it’s what you do that counts, not who you are. As a person who writes a lot, I have a certain impatience listening to writers try to justify not writing, and how you’re still a writer anyway when you don’t, blah blah blah. What if instead of having this conversation, I would think, you just sat down and actually wrote something?

Now I understand where this kind of sentiment comes from, the ways in which many women have trouble assuming authority or owning their experience, undermining themselves, the same way that Shirley Jackson was just a housewife. But it’s still putting the cart before the horse, I think, to imagine that learning to call one’s self a writer or “novelist” is even remotely the answer to the question of how to get to be a published author. (I read an old, old pre-Pickle blog post recently in which I worried that I’d spent far more time thinking about being a writer than actually writing. I was definitely on to something there…)

But even still, over the past two and a half years—as my first novel came into the world, and then I wrote two more books, and faced rejection and uncertainty about my future as a writer at all (let alone a “novelist”)—that mug served me a kind of talisman. That I was also doing the work of writing is fundamental to this story, but I came to understand how important it can be to own this little piece of legitimacy, even if it’s one that’s carved into a mug. But it mattered. It helped me keep going—and possibly keeping going is more vital to success than anything else in the world, that which can be written on a mug and otherwise.

And the other thing that helped me keep going was, as always, my blog, particularly this year, which I entered without a real sense of anything to look forward to creatively, and so I decided to delve back into the DIY blogging ethos and make those things to look forward to myself. After years of talking about creating an online blogging course, I decided to go for it—Blog School launches September 16. I also dreamed Briny Books into being, which turned out to be an altogether successful project, a triumph, even—the second round of seasonal selections will be coming your way in October.

And then to have a book deal, with the publisher/editor of my dreams, even, on top of that? More goodness than a person could ever ask for, really, and all of this a reminder that when all seems lost and hopeless, getting off the floor where you’ve been lying curled up in the fetal position is probably the best thing to do eventually.

Who knew?

April 1, 2019

The Narrative Value of Abortion

I am still not finished writing about abortion (or talking about abortion), not least because writing about abortion/ de-stigmatizing abortion / acknowledging abortion as ordinary is more important than it’s ever been with women’s reproductive rights and access to abortion under threat in a way I never anticipated they would be when I had my own abortion 600 years ago and even had the nerve to take my access to abortion for granted—how very 2002/”post-feminist” of me, right?

And there, I just used “abortion” eight times in a sentence, which I think was the general guideline put forth by Strunk and White in their Elements of Style. Something along the lines of, “Write abortion eight times in a sentence, then go do seven impossible things before breakfast.” (For six and under, you’re pretty much on your own.)

I keep writing about abortion because people with no experience of abortion keep trying to make laws about abortion, and the tyranny and injustice of that terrifies me. But I also keep writing about abortion, in fiction in particular, because it’s really interesting from a narrative point of view. As Lindy West writes in Shrill, ‘My abortion wasn’t intrinsically significant, but it was my first big grown-up decision—the first time I asserted unequivocally, “I know the life that I want and this isn’t it”; the moment I stopped being a passenger in my own body and grabbed the rudder.”’ And from a character-development standpoint, such a moment is pure gold for an author, along with the nuance and ambiguity that comes with the experience of abortion. The defiance, the agency, the courage—these qualities are what character is made of. And the variable ways an abortion is experienced by a couple too, if the pregnant person finds herself in that kind of arrangement. How it could bring two people together, or push them apart, or make clear a reality that’s been present all along.

The possibilities are endless, as to what can happen to a woman (fictional or otherwise) who has an abortion, and endless possibilities are kind of the whole point of abortion anyway. And not that all those possibilities are free and easy—what choice in any life ever comes with such certainty? But it’s about plot and richness and tension and balance, and knowing that a single thing can have two (or more) realities, that a reality can be true and not true at once, which is the entire jurisdiction of fiction.

So I am not finished putting abortion in my work, because of the fact of abortion in the world, regardless of whether or not it makes you uncomfortable. And maybe in this instance, your comfort is not the point? Instead, for the reader, finding abortion in our fiction brings home the ordinariness of abortion in the places where we live—our homes, our families, our small towns and big cities. Writing about abortion is not a question of changing the world, but instead of catching up with it, acknowledging the reality what life has been like all along.

March 22, 2019

It occurs to me that I’ve written a fantasy novel.

I’m finishing up a new draft of a novel I’ve written about a popular and charismatic politician whose career is derailed due to allegations of sexual misconduct a decade before. The novel’s central character is this man’s sometime-girlfriend, a young woman seventeen-years his junior who had been his employee—but something else has gone askew in their relationship (no spoilers) and they’re now estranged. What makes my novel interesting is ambiguity about the politician’s character, less so than what actually did or did not occur a decade ago. While the allegations against him may well be unfounded, smears in general upon his character are not exactly misplaced—he is indeed a forty year old man who a penchant for women born in the mid-1990s who happen to work for him. While none of that is illegal, it’s not a sign of impeccable character either. There is a small part of him that will concede that he has participated in an abuse of power—and (even if only in private) his mother would attest to that. She knows she’s let him get away with too much. It’s a good book, well plotted, nuanced. It’s been interesting to write the experiences of a 23-year-old woman who has no idea how much she still has to learn, who is refusing to be a victim. But it also occurs to me—thinking about Brett Kavanaugh’s face, and having read the memoir of the former leader of Ontario PC party whose own downfall inspired the premise of my story—that I have actually written a fantasy novel. A novel where a powerful man has a moment of contrition, for a moment questions his entitlement. “The defences of their choices would be vicious,” Megan Gail Coles writes in her incredible novel Small Game Hunting at the Local Coward Gun Club, which is the world we live in, instead of one where a mother might concede that her son could have hurt someone. I’m thinking of the incredible ending to Zoe Whittall’s The Best Kind of People, that devastating final sentence, that strict adherence to the status quo. When I read that book I didn’t really understanding how firmly committed are so many people to that narrative.

January 22, 2019

On Revising—or How I Learned to Spell ‘Excruciating.’

The title of this blog post is a lie, because I still don’t actually know how to spell “excruciating.” When I initially typed the title here, I spelled it the same way I spelled it in the image above, which I posted to Instagram, and some people thought my misspelling was the point. Ha ha, oh yes, Of course, it was. (Oh, good heavens, why haven’t they invented spellcheck for handwriting yet. Why?? Why??) But I am going to keep the blog post title anyway, because maybe I know how to spell excruciating now. (I do! For the time being.) And because the above comment is pretty typical of what I come up with in my own revisions. Because you’re never going to get it perfect. Revising is all about showing your work, and about accepting that many parts of your literary house may not necessarily be sound, and then getting on with it anyway.

For me, learning to revise was such a revelation. Because I’d come up as a writer in blogging, you see, where getting to Publish was the point. Any blogger too focussed on revising is never going to be a blogger for long, and I’d argue that revising, or “polishing” blog posts is really procrastination, a way to avoid that terrifying moment when your piece goes live. A blog post is always a bit imperfect, somewhat raw, a work in progress—it’s intrinsic to the form. But a story or a novel is very different, and before you get to Publish, you’ll be revising it over and and over again.

I’m writing this post now, because someone emailed me last week having just completed the amazing First Draft milestone. (Huzzah! Crack open a bottle of wine!). And she knows, of course, that this finish line is only just the beginning of another marathon, and she wondered if I had any advice to share as she launches forth. And it happens that I do.

- Celebrate all the milestones. This is a bit of wisdom I learned from Sarah Henstra a few years ago, and it’s the truest thing in this whole endeavour. A story idea, 10 000 words, getting to THE END. Sometimes you’ve got to throw your own party.

- Take breaks. When the First Draft milestone is reached, put your story away for a few weeks. Do something new and difference. Change it up. You’ll come back to your project with fresh eyes and a more open mind.

- I like to read through my draft first without making changes, but just reading it to see what I notice, what it’s like to encounter the text from the outside. This is where I make general notes (like the poorly spelled one above) that provide me guidelines for when I really get down to work.

- Notice the good bits. The stand-out lines, the great scenes, the twist that works—I leave check marks scattered throughout the ms as encouragement to my future self and to remember that it’s not all bad.

- Set quantifiable goals. I find this easiest in first drafts (1000 words a day!) but with revisions, you can set page goals or time based goals. An hour or two a day of a social media-blocking app makes a very good clock.

- Change your font, or the spacing, or the layout of your document upon embarking on a revision. Changing the look of your manuscript will open your mind to more possibilities and untether your mind from the idea that your draft is fixed.

- Don’t be afraid to cut, even your favourite bits, the ones that don’t work, no matter how much you hope they will. I find it easier to create a new file to copy-and-paste these “scraps” to. In the end, I usually end up deleting the entire file and its contents, but a temporary storage space makes the process less painful.

- I love the metaphor of sculpting for writing, and I love the revision process because this time I don’t have to conjure my materials out of the air. Now I’ve got the clay, but it’s raw, and I’ve got to shape it. Or else I’m using a chisel to scrape the layers off and reveal the real shape that’s underneath. Alright, you can probably tell I don’t actually know how to sculpt anything. But my point: everything you need is there now, and this is the part where you get to dig deeper.

- Digging is different from polishing, Keep that in mind. Once again, polishing can be a procrastination—worrying about word order, or where to put your comma. These details are important, but you can worry about them later, and preoccupation with them can keep you from ever moving forward with the real work (which is DIG DIG DIG).

- My favourite scene in Mitzi Bytes is one that was written in a later draft, and the goodness of that scene, to me, underlines my faith in the revision process. There will be parts of your book that you’ll end up writing down the line that will feel like they were there all along just waiting for you to discover them.

- Revision is an opportunity to make your book the best that it can be. It helps to embrace this opportunity, and love it. It’s a process of discovering what your book is really about, and it’s kind of amazing and mysterious that you—its author—might not even know what that is yet. It’s actually helpful to never be too sure.

- If you’re lucky, you might have someone in your life who is willing to read your unedited manuscript (which is a big request to make of anybody). Make sure it’s someone who cares about you and your work, and someone whose opinion you respect. Remember that every time someone reads your work, it is an opportunity to practice the art of receiving feedback.

- And understand that the moment of realizing that your entire manuscript is garbage (which is also EXCRUCIATING) is a part of the process too. It’s always devastating to realize that your art that was perfect in theory in reality is never quite the flawless piece you imagined. But that’s what revising is for. Onward, and better and better all the time.

December 17, 2018

Lightbulbs

I still remember the day I started writing Mitzi Bytes, in late June of 2014, and how we’d had dinner out on the porch, and I had this idea for a story, and we talked about it through dinner, the conversation providing the momentum for me to finally get started. Iris was still a baby, so didn’t have a lot to contribute but Stuart and Harriet had seemed as invested in the project as I was, and that night Stuart washed the dishes even though it was my turn so that I could sit down and begin writing.

Always for me, writing books has been a family project. We spent dinner last night brainstorming titles for my latest manuscript, a #MeToo era novel about a woman whose older politician boyfriend is accused of sexual misconduct alleged to have taken place a decade before, and that that woman herself is estranged from the boyfriend for mysterious reasons, having returned alone to their hometown months before in disgrace, only makes the situation more complicated to navigate. The novel unfolds over the week that the scandal does, the story of their relationship and his betrayal gradually revealed.

“Wow, you’ve sure done a lot thinking about this,” Harriet said to me, after drilling me on all the details, but I knew about the worn tread on the outdoor carpet on the boyfriend’s mother’s porch, and about the protagonist’s sister who runs a Montessori school, and I was more than a little proud of having impressed her. She was fixated on the hometown though, in the context of her Grade Three social studies project on communities, I think.

“Well, what’s the major industry?” she kept demanding. “Tourism? Resource extraction?” I confessed I didn’t know, exactly. I knew the town had a drug problem, opioids, and that the librarians were trained in administering Naloxone. Harriet did not consider this sufficient. “I think,” I told her, “that the town had at one point been a manufacturing base, but then the factories closed down, as they do.” But what had the factories made, she wondered. A novelist has to be specific.

“Light bulbs?” suggested Stuart. Yes, maybe light bulbs. The town doesn’t even have a name—maybe we could call it Edison. (I just googled to see if there is an Edison in Ontario, and there is, an Edison Mountain, named for a mine owned by THE Thomas Edison, but it turned out he didn’t invent the lightbulb after all? Further googling reveals that the incandescent light bulb was invented several times in various places all over the world—but it was two Canadians, Woodward and Evans, who sold a patent to Thomas Edison in 1879. Who knew?)

And then we got back to titles, and Harriet suggested the novel’s title be a warning to the protagonist: “Stay Away From That Man, He’s Bad News.” And I thought about “Bad News,” because of the role the media plays in the story. Then she and Iris started rhapsodizing other possibilities: “Love in the Darkness.” “Terrible Love Story.” “The Shadow of Love’s Heart.” “Don’t Tell Mom, The Politician is a Smarmy Git”—that one was my idea.

“Summer of Love?” Harriet suggests, but no. “What’s the season?” she asks, and I tell her autumn, fall. The novel takes place in October, and it’s raining a lot, and I start thinking about fall, falls, being fallen. “So now I now how downward spiral goes,” is a line from a poem I wrote many years ago that has found its way into my new book, which is about downfalls, the kind that happen to men and the kind that happen to women, and the distance between those two experiences. And there we had it—downfall. This Downfall. An actual title. after months of edits on Untitled Story Draft Two.

Always trust in the process of discussing my novels over dinner, might be the truest writing advice I know.