December 11, 2019

Other Dives into Other Lives

Dance Me To the End, by Alison Acheson

Alison Acheson’s memoir is all about narrative, narratives the defy the laws of narrative, or at least the commonly supposed one. After twenty-five years of marriage (and raising three sons), she discovers that she’s fallen in love with her spouse again, that they have reached that pivotal moment so many couples arrive at after years of living separately and taking the other granted—and then they decide to go on into the future together. But then the future would not stretch long, because not long afterwards, her husband is diagnosed with ALS. The decline is fast and brutal—he lives just ten months after that, and she has resolved that she will care for him at home until the end, but she didn’t really know what she is promising at the time. Told in fragments, some poems, Dance Me to the End is a memoir about marriage, aging, family illness, caregiving, and how to understand one’s own story, especially when it seems like you know the ending already (but, of course, you never do).

What the Oceans Remember, by Sonja Boon

So, before I read Sonja Boon’s memoir, I didn’t actually know where Suriname was. Beside Guyana, okay, but then I thought Guyana was somewhere in Africa, perhaps, but no. Geography is difficult—for some of us more than others, it seems—which is an underlying point to this book, with Boon attempting to understand her own personal geography and history, to connect the islands of her ancestry and experience. The memoir beginning in Newfoundland, where Boon now makes her home and raises her family, but she’d been born in the UK to parents who were Dutch and Surinamese, growing up with brown skin on the Canadian prairies, the product of Dutch colonialism, the Slave trade, with ancestors who’d come from India and Africa as indentured labourers and slave workers themselves. This memoir is an exploration of memory, archival documents, and the limits of both. It’s also about music, race, lineage, inheritance, and family, and I loved it. A truly extraordinary, entrancing work.

My Father, Fortune-Tellers & Me, by Eufemia Fantetti

A memoir that begins, “My father likes to say he was lucky that God held both his hands and stopped him from killing my mother.” Who wouldn’t be intrigued and want to read on? Fantetti is a fantastic writer (I loved her short story collection A Recipe for Disaster, way back when…), and structures her memoir with the use of Tarot cards to tell a story of her Italian parents’ arranged marriage, her mother’s mental illness, which contributes to Fantetti’s own traumatic childhood, and her complicated relationship with her beloved father, who has struggles of his own. Dark and funny, vulnerable, honest and full of love, this memoir is rich and entertaining.

Into the Planet, by Jill Heinerth

I honestly thought I kind of knew about cave diving. Because I love swimming, see, and I loved the blue of the cover, the sense of adventure. However, nope, it turns out that cave diving is nothing like I’d ever imagined, and even reading about it made my heart race, the risks, the chances. But Heinerth writes about how it’s the risk and the chance that drives her, about using her fear instead of letting it rule her, about being a woman in a male-dominated occupation, and about the endless depths of her passion for exploration, for discovery, to find parts of the world that no one else has ever seen.

Falling for Myself, by Dorothy Ellen Palmer

I’ve learned a lot from Dorothy Ellen Palmer over the years, about activism, and ableism, and how to write a novel with a twist. In her memoir, Falling for Myself, she puts the different pieces of identity together—adoptee, disabled, teacher, activist, parent, senior citizen, author— to tell the story of her life from A-Z, and she’s holding nothing back, fed up with being silent too long in a world that expects her (everyone) to conform to its impossible expectations. Palmer is fierce, and she is furious, justifiably so, but she is also witty, generous, a born storyteller, and she has created a fascinating and most compelling book.

December 9, 2019

Girl, Woman, Other, by Bernardine Evaristo

It’s so good. It’s that simple. Girl, Woman, Other is the first book by Black woman to ever win the Booker Prize (a long time coming, right?) and so you should read it, but you’ll also want to . You will start reading and not want to put this book down, and in the meantime you’ll be raving about it to strangers on the streetcar. That is, if your experience is anything like mine.

Evaristo has explained the style of the novel as “fusion fiction”: “that’s what it felt like, with the absence of full stops, the long sentences. The form is very free-flowing and it allowed me to be inside the characters’ heads and go all over the place – the past, the present.” Ostensibly about a single evening in London as a play by a Black lesbian playwright opens at the National Theatre, the novel spans the twentieth century, moves between communities in Britain, Africa and the Americas, and tells the story of twelve central characters from birth to death in a few cases, and in others to the present day. It’s a novel “about Black womanhood,” but what falls under that umbrella is wide-ranging, kaleidoscopic, diverse and disagreeing in the most fascinating way. This is a novel that’s rich with twists and connections, and surprises.

The characters include Amma, the aforementioned playwright, who recalls her radical days in contrast to now being considered establishment (or as much as a Black woman could ever be); her daughter who must find new ways to rebel against her counterculture parents; and her longtime friend and former collaborative partner, who fell in love and moved to a feminist commune in America where she becomes trapped in an abusive relationship.

The connections are not always clear at first—Carole, a superstar in the world of finance, is attending Amma’s play, but she’s part of the tapestry in other ways as well, and so is her mother, Bummi, who steers the following section, telling the story from her youth in Nigeria, her immigration to England, the death of her husband, and her determination to build a business and succeed—as well as her disappointment at how her own daughter’s success has put distance between them. And then we meet LaTisha, once upon a time Carole’s classmate, but her life took on a different kind of trajectory.

Amma’s childhood friend, Shirley, who teaches unruly youths at a London school, who started out teaching with big dreams and great ideals, which become ground into nothing after working through the Thatcherification and bureaucratization of teaching and society in general in the 1980s. And Shirley’s mother, Winsome, whose own story comes with a surprising twist, and Penelope, Shirley’s colleague, who’s got one of her own.

And then a non-binary social media influencer, Morgan, and their great-grandmother, Hattie, who lives on the family farm near Newcastle, and her own mother, Grace, which takes us to long before and far away from the opening night of Amma’s play, but everything is connected, in satisfying and illuminating ways.

That a single novel can hold so much is extraordinary —and that it can do it while being stylistically innovative and so joyful to behold is even more so. Girl, Woman, Other is magnificent, and honestly, it’s the only Booker winner you need.

June 12, 2019

Echolocation and Meteorites

Echolocation, by Karen Hofmann

As a fan of Karen Hofmann’s novels (I loved After Alice, and What is Going to Happen Next is a title I’ve been recommending widely) I’ve been looking forward to her short story collection, Echolocation, which was published in April—and it did not disappoint. The stories themselves are wide-ranging in tone and style, as well as in their publication history, if Hofmann’s “Acknowledgements” are any indication—the title story was published in Chatelaine in 1998 (and now I am nostalgic for short fiction in women’s magazines, and women’s magazines in general. But I digress). Stories are written in the first person, third person, and even one in first person plural, which I liked a lot—about a group of colleagues retreating to a cottage after a conference, and it’s an incredibly orchestrated melee. “Echolocation” is a story of miscarriage and marriage. In “Virtue, Prudence, Courage,” two misfit newlyweds turn feral on their wilderness honeymoon. In “The Swift Flight of Data Into the Heart,” a woman’s long-buried secret is beginning to rise to the surface. As in What Is Going to Happen Next, this book is impressive for its broad scope and convincingness at all corners—suburban wives and mothers, middle-aged men, a family of immigrants from Bosnia, an ex-nun, an elderly painter who clings to her independence, and former trumpet player from a travelling band of people with dwarfism, although the narrator was taller than they would have liked, but they needed trumpet players, as all bands do.

Meteorites, by Julie Paul

I was also excited to read the latest by Julie Paul, whose last book was winner of the City of Victoria Butler Book Prize and made the Globe and Mail’s Top 100. Similar to Echolocation, Meteorites is a grab-bag of various delights, whose stories whose concerns include obnoxious step-children, ghosts, teenage friendship, brotherhood, a young daughter’s self-harming, an organist determined to persist after her arm is amputated, and also murder. The settings seem familiar, but something sinister lies at their edges—sometimes surreally so—which is part of what makes these stories such compelling reading.

June 3, 2019

Gleanings

Whew! A bumper crop of good things to read online this week (or “on the line” as my youngest daughter said to me today when she was trying to explain something she’d seen on the internet). Gleanings was on hiatus last week while I was on vacation, which means I’ve got even more than usual to share this time. Thank you, as always, for reading!

- First, I stumbled upon a Chuck E. Cheese training video from the 1980s when I was procrastinating on my master’s thesis.

- I was already in love with notebooks and spying before I met Harriet, but she made that okay.

- How Claudia Kishi Inspired A Generation Of Asian American Writers

- What are children to do when they realize that the adults in their lives are making it up as they go along.

- This year I even considered scaling back the unicorn party as a sort of white flag gesture.

- What my mother likely hadn’t considered until that moment was that my books, and my Anne books in particular, were the constants in my life.

- You want to be building community, so that when you need to access community, community’s there for you.

- This is what it looks like to have a feminist husband.

- What I’ve learned from being vulnerable is we are not alone, we are all different, and we all desire to be accepted and accept ourselves fully in this journey we call life.

- it’s the swim cap, it gives me a facelift

- What are your indelible words?

- My goal is to make this summer all about having fun in the water.

- Holy cow. Can you even believe an amazing baker is whipping up ’embroidered’ cakes?

- nanaimo ice cream bars (!!!)

- I have learned the hard way that this is a lesson that everyone comes to in their own time–if a friend is fretting endlessly about what to wear to a party, “What makes you think everyone is going to be looking at you?” is not an immensely helpful thing to say.

- Over the years we’ve lived here, I’ve grown to love the homing pigeons that live a few doors down.

- I’d be a faster reader if I read one at a time, I imagine.

- It’s a bit of a shame that the in-between has not really had its time to shine, isn’t it?

- I’m especially glad that I can keep the old and useless and rejected in use a bit longer.

- If any of the eyeballs in your manuscript make sparks or are steely or artless, I would further invite you to try to make that happen and ask someone to tell you exactly what you’re doing with your eyes.

- Women acting collectively in open and angry defiance can change history…

April 8, 2019

Gleanings

- If you’ve heard me talk about the library, you’ll know that I value the photocopier as one of the unsung heroes of human exchange.

- 17 Strategies of a Born-Again Reader

- It’s time for the men to listen and to record and to stay quiet.

- You get what you get, when you get a child.

- Choose Kindness! Kids Books that Explore This Crucial Value

- But where it comes to that question – the one of whether or not to bring new life onto the planet, by way of my body – I and my presently fertile peers have chronologies to consider beyond our own.

- When I was first diagnosed I turned to Jilly Cooper…

- How an Email to an Astrophysicist Changed My (Book’s) Life

- Think about how things like desolation, sadness, an imbalance in the universe, even, have a way of sharpening us, too

- …we’ve allowed our friendship to steep and stew, to mature; gathering dust at times, shining brightly at others. Never discarded. Complex, still vital, preserved and cherished.

- The water and its glorious buoyancy makes all of us athletes.

- Lord Peter Wimsey, from the beginning

- Although I was often warned about getting Blasenguitar and I understood from the way she said it that it was painful and I would be sorry, she never explained what it was.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

April 4, 2019

A Mind Spread Out on the Ground, by Alicia Elliott

One of the first essay collections I ever fell in love with back when I was first falling in love with the essay was Pathologies, by Susan Olding, who was later kind enough to write a short piece at 49thShelf about the essay form. Olding wrote, “In an unstable world, we want to know what we’re getting, and with an essay, we can never be sure. Partaking of the story, the poem, and the philosophical investigation in equal measure, the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go. Places we may not want to go. We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave. That’s the risk we take when we pick up an essay.”

It might be the risk, but it’s also the reason, as demonstrated by Alicia Elliott’s remarkable and now-bestselling debut, A Mind Spread Out On The Ground. A collection of essays that examine stories and ideas from all angles, not one side, or even (more importantly in this age of polarization) both sides, but instead acknowledge a myriad of viewpoints, or points of consideration. These are essays that resist certainty, neat conclusions, simple morals. Instead: there is multiplicity, complication, tension, and this is what makes the book so fascinating. “Sontag, in Snapshots” begins with self image and photography; and then photography and colonialism; Black Lives Matter and video recordings of police brutality; on photography and agency, and also community; cultural stigma of “selfies” and misogyny, and imperial beauty standards; and photography as “a family building exercise;” then landscape photography in Banff vs. the Kinder Morgan pipeline and how some mountains are more worthy than others; and torture a Abu Ghraib; revenge porn; and what it means to have one’s pain witnessed, corroborated. It’s an essay that ends with questions instead of answers, ever expansive, “Why do we need our lives to be witnessed? Why do we need to share our experiences, to have this connection to others? Why do we need to control others so badly and so completely that we will even try to control their image? Is it because we’re trying to make ourselves more real? Is it because that power—as expansive or minuscule as it may be—fills a void?”

As Olding writes, “the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go.”

While Elliott’s essays—which portray her experiences growing up in poverty, as an Indigenous woman, as the child of a mother with mental illness, a teenage mother herself, a survivor sexual assault—recall (in the best way) the groundbreaking work of Roxane Gay in her collection Hunger—a collection that also lays bare the experience of trauma—they are also different in tone. While rawness is a feature of Gay’s essays in her collection, Elliott’s are more processed, polished, synthesized in a way I hadn’t entirely been expecting from someone who (admittedly, in addition to winning magazine awards, being awarded the RBC Taylor Emerging Writer Prize, being nominated for the Journey Prize, and appearing in Best American Stories, so we should have seen it coming) has made a name for herself with incisive Twitter threads and having none of your racist bullshit on that particular social media platform.

But with her first book—which is eminently readable, absorbing and hard to put down—Elliott solidifies her reputation as a profound thinker and prose stylist, in addition to being a Twitter powerhouse. Perhaps the tweets are where her rawness is, but readers of her essays will find a voice more cool and discerning, and oh-so-fucking smart. Good luck trying to mess with “Not Your Noble Savage,” a consideration of literary colonialism that is coming at you with receipts (as they say on the Twitter), with Margaret Atwood in an essay claiming that Pauline Johnson (as an Indigenous writer) is not “the real thing,” but Thomas King (“the son of a Cherokee father and a Swiss, German and Greek, ie white, mother”) gets to be. “[L]et’s consider Canada’s history of dictating Native identity,” proposes Elliott, and then this leads to considerations of how Indigenous writers’ work is “policed” by critics, and the charade of reconciliation, and “the fairy tale that keeps Canada’s conscience clear.”

Recalling Olding’s, “We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave.”

Oh, the places where these essays take us. She writes about learning the verdict in the Gerald Stanley case, on trial for the killing of Colten Boushie, while visiting the space centre in Vancouver while on vacation with her family, “dark matter” as a metaphor for racism—”it forms the skeleton of our world, yet remains ultimately invisible, undetectable.” I haven’t had lice since February (knock on wood) so was able to read her essay “Scratch” without too much creepy-crawly imaginings. She writes about mental illness, and the Mohawk phrase which describes it, which is where Elliott’s collection gets its name. About being Indigenous while looking white, and her ambivalence about her child receiving the same inheritance; on cultural appropriation and what it meant when she read Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s Islands of Decolonial Love, the first time she’d read the work of another Indigenous woman—she writes, “Every sentence felt like a fingertip strumming a neglected chord in my life, creating the most gorgeous music I’d ever heard.”

I’ve not even touched on her essay about Toronto’s Bloor and Lansdowne neighbourhood, about gentrification; the one about nutrition, poverty and its colonial legacy; about her marriage (“Antiracism is a process. Decolonial love is a process. Our love is a process…”) About attempting to understand and love her complicated and troubled mother. Her essay, “Extraction Mentalities,” which is a “participatory essay,” something I’ve never encountered before, with literal space on the page for the reader to engage with her questions. And throughout the entire book, really, Elliott has created space to engage with her questions, the entire project infused with this characteristic generosity. To be at once fierce and powerful, but also vulnerable and tender—what a gift that is to her reader. And what a gift this whole book is, strumming a neglected chord that the world needs to hear right now.

December 10, 2018

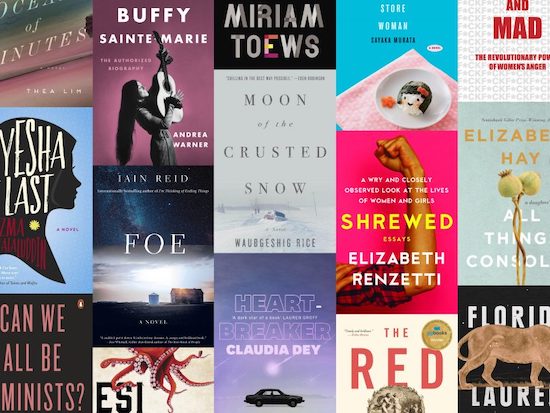

Chatelaine: Books of Year

I cannot overstate the pleasure I had being tasked with creating Chatelaine’s 2018 Books of the Year last, and how pleased I am with how it turned out. You can read the whole list here. And lucky me, I also got to help create the Books of the Year list at 49thShelf—there is definitely some overlap. And stay tuned for the Pickle Me This Books of the year list, coming up sometime later this week.

September 17, 2018

Motherhood and the Map

In July, Lauren Elkin wrote an essay about a new and sudden influx on books about motherhood, and I rolled my eyes at the idea. Because of course Lauren Elkin is pregnant with her first child, which is around the time that most literary people discover the existence of a motherhood canon. “Motherhood is the new friendship, you might say. These are books that are putting motherhood on the map, literarily speaking, arguing forcefully, through their very existence, that it is a state worth reading about for anyone, parent or not.” Which annoyed me not just because after nearly a decade of motherhood, because of course it’s been on the map all along—and I even did my part to expand its boundaries by editing The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood in 2014. But also because Elkin’s discovery of motherhood reminds me of my own earnest revelations of a decade ago, that parenting indeed is not “a niche concern,” and it’s a little embarrassing to see one’s naivety reflected in such stark terms.

In July, Lauren Elkin wrote an essay about a new and sudden influx on books about motherhood, and I rolled my eyes at the idea. Because of course Lauren Elkin is pregnant with her first child, which is around the time that most literary people discover the existence of a motherhood canon. “Motherhood is the new friendship, you might say. These are books that are putting motherhood on the map, literarily speaking, arguing forcefully, through their very existence, that it is a state worth reading about for anyone, parent or not.” Which annoyed me not just because after nearly a decade of motherhood, because of course it’s been on the map all along—and I even did my part to expand its boundaries by editing The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood in 2014. But also because Elkin’s discovery of motherhood reminds me of my own earnest revelations of a decade ago, that parenting indeed is not “a niche concern,” and it’s a little embarrassing to see one’s naivety reflected in such stark terms.

The other week, two of my library holds came in at once: Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, by Kate Manne, and And Now We Have Everything: On Motherhood Before I was Ready, by Meaghan O’Connell. I read Down Girl at once, and found it illuminating and really profound. I’ve since had to return the book—there are many holds on it after mine—but if I still had a copy here I’d been sharing the lines where she writes the misogyny inherent in our understanding that the history of feminism occurs in waves, each one sweeping away whatever came before. Instead of us there being a more constructive model of this history, something indeed that is cumulative. I was struck by this idea, by the way that waves must undermine us. As Michele Landsberg explains in Writing the Revolution: “Because our history is constantly overwritten and blanked out…., we are always reinventing the wheel when we fight for equality.”

I didn’t pick up Meaghan O’Connell’s memoir at all, however, until I received a note from the library that it was two days due. I’d been resisting the book for ages, since seeing it in the bookstore and deciding I didn’t want to pay the price of a hardcover for a book that was slight, so I was content to be the hundredth-something library hold, and even once I brought the book home, as I’ve said, I still didn’t read it. Partly for the same reason I found Lauren Elkin’s essay annoying. “We have lacked a canon of motherhood, and now, it seems, one is beginning to take shape.” OH GOD, NO. (Note: Please read my review of Val Teal’s amazing and irreverent 1948 mothering memoir, It Was Not What I Expected: “It is often said that nobody tells the truth about motherhood, though I think the reality is really that nobody ever listens.”) I’d read enough motherhood memoirs for one lifetime, I decided. There was indeed nothing new under the sun, even if you happen to be raising your baby in Brooklyn.

But then it wasn’t a very long book—the very reason I hadn’t bought it. Perhaps I could even get it read in two days (because such expansiveness is possible in the life of a mother whose children are nine and five). There were many holds on this book as well and it could not be renewed, so I picked it up and started reading, and what happened next, like motherhood, was not at all what I’d expected.

Reader: I really, really liked it, this story of a woman who got pregnant when she was 29 and decided to have a baby before she even owned a home or a car. Unlike O’Connell, my baby was planned when I got pregnant when I was 29, but we were similarly missing the house and car and career stability (actually we’d just decided to skip those) and there were people who, when they heard I was pregnant, had asked me, “Oh, Was it planned?” I identified so much with O’Connell’s story of motherhood before she was ready, and it brought back so many memories I’d forgotten about altogether—like when she jumps up from the table at last once a week to run to the bathroom because she’s convinced she’s started to miscarry and then comes back sheepishly, “False alarm.” How the pregnancy never feels real, except for about forty minutes after she’s had a sonogram. About reading Ina May Gaskin and deciding that you too can be a hero. And once her baby is born—that failure of imagination. The double standard of a society that demands you breastfeed but doesn’t know where to look when you do it. O’Connell writes that she’d known it would be hell, but had imagined the hell would be logistical instead of emotional. And that was the part where I put my finger on the line of text and shouted, “Yes, this exactly.”

I’d forgotten so much of it—and I have probably read and written about motherhood more than the average person. But so much of the story had disappeared from my consciousness, swept away—like as a wave, as it will. And I’d even decided that stories of new motherhood were no longer relevant to me, that I was done with al that. The same problem as Lauren Elkin but in reverse. Scoffing, of course, there’s always been a motherhood canon, but now it’s dusty on the shelf and I don’t even need to read it.

There might be something to the waves, something more than misogyny. I wonder if men’s lives are more linear than women’s, whereas I know that in my own experience, with motherhood in particular, my self has been continually overwritten. As it has been again now that my children are more independent, and as it will be when they get even older, and then with menopause—all these changes. I don’t remember who I was before. I don’t remember when I ever needed those books. Sometimes I pick them up and read my notes in the margins though, and it’s like they were written by a stranger.

September 12, 2018

Unabashed

I remember the first time I had courage to stand up and confront an anti-abortion protester. It was the summer of 2015 and I’d just dropped off Harriet at day camp, and the year before I’d published an essay about how becoming a mother taught me everything I knew (and was grateful for) about my abortion. Which meant that I’d thought about abortion a lot, and was comfortable talking about mine in public, and had a lot to say about my experiences, actually. Even though I usually shy away from conflict, and don’t get off on debate just for the fun of it (because, unlike a lot of anti-abortion protesters, it’s my bodily autonomy we’re talking about. These ideas, for me, aren’t abstract, and I will probably cry). These people are able to dominate the abortion conversation like they do because most of us don’t know how to talk about our abortions in public (and why should we have to? We don’t require men to issue public defences of their prostate surgeries). But I’d had enough to having these people be the loudest people when we talk about abortions, of their taking advantage of civility and politeness to scream the loudest. I was ready to talk, and so I did, and it was exhilarating, and terrifying, and very empowering to be able to tell this young man holding a sign: “I KNOW MORE ABOUT THIS THAN YOU DO. YOU’VE GOT A SCRIPT, BUT THIS IS MY LIFE STORY.”

Unfortunately, however, arguing with these zealots gets you nowhere, and while it feels good not to be silent, these conversations are always a waste of energy. So I had this idea that maybe I could make a sign, and luckily I’m married to a standup guy who makes signs for a living (among other talents) and so I said to him, “What if you made me a pro-choice sign I could fold up and carry in my purse? So I could have it on my person at all times in case of an emergency, and be there are represent and have my voice heard, but not have to talk to these abusive nefarious creeps that get off on turning women’s private experiences into public spectacle?” And my husband said okay, and he designed my sign and had it printed, and I’ve been carrying it around for nearly two years now, but there’s that rule about only ever having a thing when you don’t need it. I’ve not seen anti-abortion protestors since the Christmas I found my “My Body My Choice” sign under the tree. Which I wasn’t sorry about—maybe the sign was like some sort of repellant, and in that case, good riddance. I had my sign and women in my neighbourhood were free to walk about the streets without the abuse of gory and misleading photos of fetuses.

But no repellant lasts forever, it seems, because today I got word of the usual suspects setting up shop a few blocks from my house. So I walked over there, where a respectable counter-protest had been set up by Students for Choice and I was honoured to join them with my little sign (and my actual life experience, which is short on the ground on the pro-life side). And there I stood for an hour as people said thank you and others rolled their eyes at the display, and men stood behind me having rhetorical arguments on the matter of my bodily autonomy and didn’t seem anything ironic about that. As I said so beautifully in all-caps on Twitter: “Do you know what’s more arbitrary than Canada’s lack of an abortion law so that abortion is a decision between a woman and her doctor? AN ABORTION LAW DECIDED BY SOME RANDOM GUY ON THE SIDEWALK.”

This morning I read Anne Kingston’s article about plans afoot by the anti-abortion movement to make their cause a political issue everywhere, and it’s terrifying. It’s terrifying, because the most of us are going to continue to be civil and polite and let them continue to dominate the discourse with misrepresentation and lies—all the while our reproductive rights are eroded. But my daughters—who would not exist were it not for abortion and the choices I was free to make—deserve to have the same freedoms that I was lucky enough to be able to take for granted. And it’s not even just about them, or about abortion either—THREAD, as they say: “Reproductive justice is about bodily autonomy, it’s linked to racism and immigration and incarceration, it’s about classism and supremacy, it’s all connected to climate change and accessibility and colonialism…” writes Erynn Brook.

Reproductive justice is linked to everything, and it’s about standing up and speaking out for our rights right now. As unabashed as we want to be. About this, there is no choice—it has never been more important.

August 30, 2018

Women Talking, by Miriam Toews

“No Ernie, says Agata, there’s no plot, we’re only women talking.”

Women Talking, the latest novel by Miriam Toews, is not an easy read. Not easy because of the places it takes its readers to—the women talking in Women Talking are women from a Mennonite community in Bolivia, women whose husbands/brothers/sons have been accused to raping the women while they were sleeping, incidents based on real events, so-called “ghost rapes,” and it’s how women respond to and try to move on from this trauma that raised important questions for Toews as she considered writing this book, more than the fact of the violence itself. Because violence is ubiquitous. As Toews said in conversation with Rachel Giese when I went to see her last week, she can imagine what a rape is like. But what happens after—how do you imagine a way through that? And then she said something else, an echo of line in the novel which I read a few days later: “We are all victims, says Mariche./ True, Salome says, but our responses are varied and one is not more or less appropriate than the other.”

This line reminded me of Jia Tolentino’s article in The New Yorker on The Women’s March in 2017, and the way that so many were quick to jump on organizational conflicts and disagreements as a way to dismiss the movement altogether. Scoffing is often what happens when we hear about women talking—it’s either idle gossip, or else a petty scrap. A catfight. Women talking—it’s on the background, unless the voices are shrill. Or when they’re allowed to be a chorus. But in her novel, Toews dares to make women talking everything. The “there’s no plot” line is a funny meta-joke. But this is difficult too, on a practical level. To follow along with the conversations, to discern who these people speaking are as we’re just beginning to know them as characters. And Toews complicates the work further by refusing to make any of her characters just one thing—these are women who are difficult, who argue with each other out of spite, who contradict themselves and turn their own arguments inside-out, because this is what thinking is. For the first half of the novel, I confess that I was a little bit lost, finding the narrative hard to follow, and not remotely sure how the whole thing would come together.

But then mid-way through, something happened—it was like the walls started closing in on the threat to these women in the hayloft talking, these women who were daring to defy their husbands, brothers, sons. To explore the three options available to them: do nothing, stay and fight, or leave, but then the men who’ve gone to the city to post bail for the others could return at any time. And suddenly this novel without a plot takes on the most furious momentum and becomes unputdownable. In this novel in which nothing’s happened yet, something is going to have to give—but what?

The women talking in the novel are people who’ve never learned to read or write, who cannot read a map, and know nothing about the world beyond the boundaries of their communities. (I read this book right after Claudia Dey’s Heartbreaker, which is such a completely different novel in spirit, but there’s a kinship between them.) As the women in the novel are illiterate, writing down the minutes of their meeting is tasked to August Epp, an estranged member of the community who has returned after years away to serve as a school teacher (which is basically to be a failed farmer, and shameful occupation for a man). And August’s own complicated story, and his love for Ona, one of the women whose words he’s recording, becomes a foundation for the novel, as it would be, although just why or how does not become apparent until the conclusion, which only adds to its devastating and beautiful ambiguity.