April 15, 2024

The M Word Turns 10

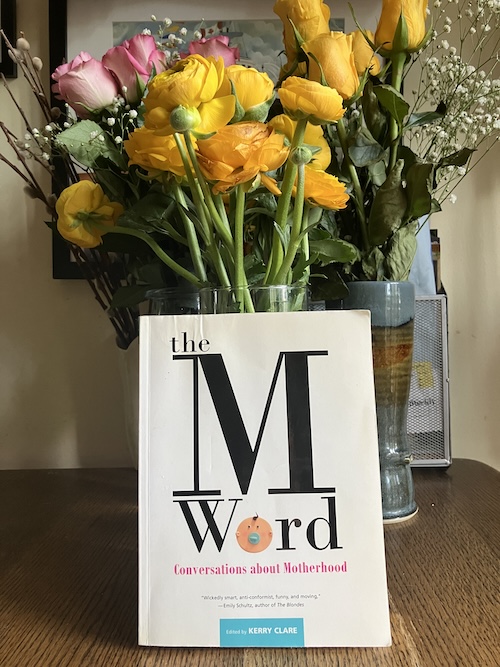

It’s been a decade since THE M WORD arrived in the world, a book that was born because I couldn’t see a reason why stories of motherhood should not include those of women who wanted children they never had, those who never wanted children at all, parenting stepchildren, being mother of children who’d died, experiences of miscarriage, maternal ambivalence, abortion, adoption, single motherhood, motherhood via IVF—AND MORE—could not all be included within a single volume. And what a volume it is. I love this book, and am so grateful to its contributors—including the inimitable Priscila Uppal, who died in 2018—for their generosity in sharing tender and intimate stories with such candour, insight, and brilliance.

Happy Anniversary and thank you to Heather Birrell, Julie Booker, Diana Bryden Fitzgerald, Myrl Coulter, Christa Couture, Nancy Jo Cullen, Marita Dachsel, Nicole Dixon, Ariel Gordon, Amy Lavender Harris, Fiona Tinwei Lam, Deanna McFadden, Maria Meindl, Saleema Nawaz, Susan Olding, Alison Pick, Heidi Reimer, Kerry Ryan, Carrie Snyder, Patricia Storms, Sarah Yi-Mei Tsiang, Julia Zarankin, and the amazing Michele Landsberg.

I’m so proud of this book.

Order a copy wherever books are sold!

April 30, 2020

Catching Up with THE M WORD

Last week, I was asked to blurb a memoir that’s coming out this September, and I was happy to say yes to this request, though I always have trouble reading books that aren’t actual books yet, and especially when they’re digital, because I’d have to read on my phone, and who wants to do that. But this book. Which I received on Friday and had finished by Monday night. On my stupid phone. Do you know what an endorsement that is?

The book is How to Lose Everything, by Christa Couture, and it’s a story that sparkles and sings. A story for anyone who would like to consider ways to find grace and keep going in the face of a hopeless situation. Amazingly, it’s also a book that was born out of the essay that Christa published six years ago in The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood. What amazing seeds that book has planted!

Which made me consider all the remarkable things that contributors to The M Word have been up to in the years since the book was published. I continue to be bowled over with gratitude to all the women who contributed to our project, and want to celebrate what some of them have been recently been up to literary-wise.

But first, I want to note the death of Priscila Uppal in September 2018. Uppal’s essay was “Footnote to the Poem “Now That All My Friends Are Having Babies: A Thirties Lament,” and it was funny, brutal, honest, and necessary. I am still so honoured that her work was a part of our collection.

- Heather Birrell’s latest book is the poetry collection, Float and Scurry, which has been shortlisted for the 2020 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award

- Christa Couture has just released her fifth album, Safe Harbour. Her memoir How to Lose Everything will be published in September.

- Nancy Jo Cullen’s debut novel The Western Alienation Merit Badge was published in 2019.

- Marita Dachsel’s most recent book is the poetry collection There Are Not Enough Sad Songs

- Ariel Gordon released the essay collection Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests in 2019. It has been nominated for the Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Award

- Fiona Tinwei Lam’s poetry collection Odes & Laments was published in 2019.

- Maria Meindl’s debut novel The Work was published in 2019.

- Saleema Newaz’s new novel, Songs for the End of the World, was due to be released in August. Due to uncanny connections between her novel—about a coronavirus that sweeps the world in 2020—and our current moment, the book has been released early as an ebook and the print book is coming this summer.

- Patricia Storms’ most recent book is the picture book Moon Wishes, co-written with Guy Storms and illustrated by, Milan Pavlovic published in 2019

- Julia Zarankin’s first book, Field Notes from an Unintentional Birder, is coming in September (and I can hardly wait!)

This is just a smattering of updates from our contributors, all of which have been up to good and interesting things in the years since the book came out. What a pleasure it is to have this connection with each and every one of them.

July 25, 2016

Christa Couture and #TheMWord on the radio

Singer, songwriter, storyteller, cyborg, halfbreed (and then some) Christa Couture was on CBC Unreserved last night, which is the show I generally spend Sunday evenings washing the dishes to. Christa, who is a wonderful musician—her latest album, Long Time Leaving, is terrific—was talking about music, her Indigenous identity, and also about motherhood and what it means to mother after loss. She gave a kind and generous shout-out to The M Word and read a little bit from her essay, which so many reviewers over the years have cited as a highlight of the collection. I remain ever so glad that she was part of the book.

Singer, songwriter, storyteller, cyborg, halfbreed (and then some) Christa Couture was on CBC Unreserved last night, which is the show I generally spend Sunday evenings washing the dishes to. Christa, who is a wonderful musician—her latest album, Long Time Leaving, is terrific—was talking about music, her Indigenous identity, and also about motherhood and what it means to mother after loss. She gave a kind and generous shout-out to The M Word and read a little bit from her essay, which so many reviewers over the years have cited as a highlight of the collection. I remain ever so glad that she was part of the book.

June 28, 2016

Book Publishing: The Long View

Yesterday I responded to a tweet by Joni Murphy (remember Joni Murphy? She wrote the wonderful novel Double Teenage that I devoured last month) about the ridiculously small window of books coverage in the mainstream media. She’s absolutely right—once the “new release” glow fades, so does a lot of interest…but I suggested that this doesn’t matter. I mean, yes, it would be altogether excellent to find oneself on a bestseller list the week one’s book was published, and for the momentum to be undeniable and inexhaustible, and to have your book be everywhere. Yes, authors do need to work and hustle to get the word out for sure. But here it is: you can only do the best that you can do. And even that is not really guaranteed to get results. And so what an author really needs to do is be satisfied with immediate coverage, but also keep the long view, and have faith in the book and its readers.

For sure, this kind of faith is not the stuff of bestsellerdom, but ultimately it is what really matters. It’s the difference between your book living on someone’s bookshelf for years and years, and being put out on the curb. It means your book not being available en-masse at secondhand bookstores six weeks after the pub date (and hello copies of The Nest and The Girl on the Train. I see you!) It means real people connecting with your work rather than just hearing about it, knowing the cover. The thing about books, good books, see, is that they have long lives, even if it’s hard to measure just how. Although the most excellent thing about the internet is that we do have some kind of a record now, a way of registering reader responses long past the on-sale date. (“The standards we raise and the judgements we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work,” writes Virginia Woolf in her 1925 essay “How Should One Read a Book,” anticipating the literary blogosphere[s]). It would be really wonderful to write a book that set the world on fire, but it’s just as stunning for me as a writer to discover, say, that my book is still being picked up and appreciated over two years after it first was published.

My point proven by two things that happened after my exchange with Murphy: last night I discovered a blog post from last month by the fantastic Red Tent Sisters (who I met when they were at our book launch way back when…) called “Why Is Mothering so Difficult?” It’s a terrific post, but I was even more thrilled by their suggestion that reading a book like The M Word might make mothering a little bit less difficult. They’ve also included The M Word on their Top Fifty Beautiful Books for Soul Sisters, which you can receive if you sign up for their newsletter (and here’s a tip—if you put somebody’s book on a list they receive if they sign up for your newsletter, that somebody will ALWAYS sign up for your newsletter). So I was feeling pretty good about that, and then this morning I was tagged on Instagram by a woman called Leah Noble with a gorgeous photo of The M Word alongside a just-as-delicious-seeming breakfast. Two signs from the universe that the book goes on, after a while of radio silence. Yes, both readers are connected with writers in the book, so I’m not suggesting that the whole thing is made from fairy dust, but there is an element of serendipity about it. You really do have to trust that the book will find its way—and the good books really will. Even if sometimes the ways are small and quiet.

My point proven by two things that happened after my exchange with Murphy: last night I discovered a blog post from last month by the fantastic Red Tent Sisters (who I met when they were at our book launch way back when…) called “Why Is Mothering so Difficult?” It’s a terrific post, but I was even more thrilled by their suggestion that reading a book like The M Word might make mothering a little bit less difficult. They’ve also included The M Word on their Top Fifty Beautiful Books for Soul Sisters, which you can receive if you sign up for their newsletter (and here’s a tip—if you put somebody’s book on a list they receive if they sign up for your newsletter, that somebody will ALWAYS sign up for your newsletter). So I was feeling pretty good about that, and then this morning I was tagged on Instagram by a woman called Leah Noble with a gorgeous photo of The M Word alongside a just-as-delicious-seeming breakfast. Two signs from the universe that the book goes on, after a while of radio silence. Yes, both readers are connected with writers in the book, so I’m not suggesting that the whole thing is made from fairy dust, but there is an element of serendipity about it. You really do have to trust that the book will find its way—and the good books really will. Even if sometimes the ways are small and quiet.

And here’s another thing that I discovered last night, the other side of the publishing coin, eight months before the release date. My novel Mitzi Bytes is now available for pre-order, and unless I have a rabid superfan I am unaware of, my sister purchased the very first copy last night. But this doesn’t mean that it’s too late for you: you can pre-order the book at Chapters Indigo, or from Amazon, or head over to your local proper bookshop to do so.

(But my point is that even if you don’t, it doesn’t fundamentally matter. Life is long and good books are even longer.)

May 5, 2016

The M Word: Ariel Gordon’s Additional Dependent

This is the sixth in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From previous weeks: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“; “Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self”; “Dear Me, by Nicole Dixon“; “Kerry Clare on Motherhood and Abortion” ; and “Christa Couture: Ever Since the End.”

“Primipara,” Ariel Gordon’s essay from The M Word about her choice to have one child, was one of the most widely remarked upon in the book’s critical responses—not least for its inclusion of her poem of the same name which began, “If I had had twins, I would have eaten one.” It was Gordon’s essay that earned The M Word its unlikely place on Brain Child Magazine’s Humour Book List last year. And now she catches us up to the very surprising news that her family has since acquired a new addition.

*****

My partner and I were together for seven years before we got knocked up.

It took us another decade to acquire an additional dependent.

In those ten years—the age of many of my friend’s marriages before they busted up—we had a tank full of fish which included Downie, a black Asian Upside-down Catfish.

We hand-fed Downie shrimp pellets, until those weren’t enough and s/he started eating everyone else. (One fish leapt to his/her death to avoid Downie’s jaws-of-death. S/he became fish-jerky between the dresser where the tank sat and the wall: “It smells in my room,” my daughter noted.)

We surrendered Downie to the pet store. We didn’t mention s/he was a cannibal.

Next we got black-and-white Mollies, which are starter fishes like Tetras, the difference being that they are prolific breeders. One female came pre-loaded with enough sperm that she gave birth every month for six months. She was the alpha: she got huge and monstrous and wouldn’t let any of the other Mollies eat, nipping their fins and head-butting them. And then she’d release a brood of baby Mollies, which looked like flecks of ash. They’d hide in the aquatic plants we grew in the tank, which came from the store infested with snails.

We surrendered entire litters of small black Mollies to the pet store.

After we drained the fish tank, my daughter pined, though she’d shown very little interest in the fish.

“I want a real pet,” she said. “Can we get a real pet?”

The summer after we drained the tank, we found a greeny-yellowy wild salamander swimming in the pool with us at the water park in Portage La Prairie. That fall, someone brought a carsick hedgehog to daycare. (“It pooped on two of my friends,” my daughter reported, excited.)

So we had serious conversations about salamanders, lizards, and geckos and then hedgehogs, guinea pigs, and rats. Anna pushed for a cat or a dog, though what she really wanted was a perpetual kitten or puppy. I resisted, citing my furry-animal allergies, but was glad that the conversation was about having-a-pet and not about having-a-sister/brother.

Now, I don’t watch kitten videos or hunt baby animals on the Internet. But when summer rolled around again and a friend posted pictures of a small white kitten stretched out, yawning, I felt a pang.

A friend of hers was trying to find homes for three kittens, including the white one. It turned out that I knew the friend-of-a-friend, so one Sunday, we went to go see them. The girl could barely contain herself on the way there, but neither of us connected with the kitten, so next we visited a no-kill shelter. I sneezed, my nose dripped, but we were both suddenly determined.

A week or so later, we brought home a half-grown black-and-white cat.

We only wanted one child and we similarly only wanted one cat. Not two or three, or a cat and a dog. One cat. But, unlike my daughter, we’ve so far managed to keep the cat out of our bed.

My boss and I commute to work together. When I told him we’d gotten a cat, he had one question.

“Who’s home the most?”

“I am,” I answered.

“She’ll love you best, then,” he said. He said with pets it’s a combination of who spends the most time with them and who feeds them.

This logic could equally be applied to children, of course. Mothers are still most often the ones home with their children when they are babies, primarily because they gave birth to them and have the boobs with which to feed them with. But I’m sure half the reason that mothers often have such strong bonds with their children is because they spend all those endless early days and weeks and months with them, skin on skin.

My boss was right. Given a choice, Kitty prefers to sit on my boobs, wedge her knobby spine under my chin, and listen to my heartbeat. She bunts my glasses aside, spreading contentment pheromone all over the bones of my face. If she’s feeling particularly tender, she licks my eyelids.

According to the Internet, this is submissive behaviour. She’d do the same to the alpha if she lived in a community of cats. She also rolls on the ground the moment the front door opens, showing her belly, as if to say “Hello, big hairless cats! Please love/feed me…”

Nowadays, people refer to their pets as furbabies and to themselves as their pets’ parents. But I prefer to think of myself as a cat that is slightly higher than Kitty in the social hierarchy. I have certain responsibilities to her—and affection for her— but I am not her parent.

Last night, after the girl had gone to bed, I was sitting on the couch and Kitty assumed her usual position. Except this time, she reached out and softly put her black-and-white paw on my eyelid. After a few moments, she tucked both paws under her body and promptly fell asleep.

When I was breastfeeding my daughter, I was often aware that I was putting my nipple into a mouth full of irrational teeth, that I was trusting her not to bite me.

Kitty’s paw is full of sickle-shaped claws. Her mouth is full of needles. But I am still willing to offer her my softest bits.

I’m good with animals, even if I don’t need them, if that makes any sense. When I was a kid, delivering newspapers in my neighbourhood, I came to an understanding with each of the neighbourhood dogs. They stopped barking at me when I entered their territory; some of them even offered me their bellies to rub.

Once, I was walking down my street at night and saw a dog-shaped animal twenty feet away. When I got a bit closer, I saw that it was a red fox. But I still bent down and offered my hand and said soft things, trying to tempt it to closer. We looked at each other for long moments, but it was wild and eventually loped away. I hold that memory close, the same way I hold the memory of watching my late uncle dandle my youngest cousin when she was two weeks old, the way I hold the memory of that hot summer when my daughter was born, how naked we both were.

My daughter had hoped that the cat would be hers, that it would love her best, but I tell her that Kitty loves all of us differently. I tell her she has to be more patient with the cat, let it come to her, but she’s almost ten now and isn’t very patient.

What’s more, she’s starting to push me, alternating pouting with correcting every single thing I say. I am embarrassing, she says.

I tell her I could be much more embarrassing, given half a chance. She squints at me.

Today, between karate and groceries, the girl was hungry, so we stopped at Tim Horton’s for a bagel and cream cheese. And she pouted because I wouldn’t get her a Frozen Lemonade or a Maple Cinnamon French Toast bagel, restricting her to the tap water I’d brought from home and a Twelve Grain bagel.

We’d made it through the drive-through and were sitting at the light and she was lifting my water bottle to her mouth when the light changed. I moved smoothly into the intersection and had just completed my left turn when she yelped.

“What?” I said.

“Waaaaaah,” she replied.

“Anna, what?”

“You—jerked—the car…”

“Anna, I was driving. I didn’t jerk the car.”

“You made me spill the water all over myself…”

A sniffly moment of silence.

“Here, blot yourself.” I passed her the box of tissues I keep in the front seat.

“I don’t even know what that means.”

“It means pat yourself with the tissues.”

“Like that’ll make a difference…”

“Anna—“

“What!?!”

“I’m starting to get mad…”

We spent the rest of the trip to the grocery store in silence. After we’d found a parking space, I handed the girl a coin and asked her to go get a cart.

I’d opened the trunk and was preparing to transfer our bags and bins when Anna returned, parking the cart next to the car.

“Mama,” she says, her face pink from crying and bashful. “Can I have a hug?”

And I didn’t need the Internet to tell me that this was submissive behaviour. That she was trying to apologize for shouting at me and for pouting before that.

But the difference between Anna and Kitty and even the neighbourhood dogs of my childhood is that my relationship with my daughter is slippery; we are both alternately dominant and submissive. More than that, we are just people, trying to get along, even if I built her in my body, cell by cell, limb by limb.

“Yes,” I say. And I pull her close, holding her tighter than usual. I want her to remember that once neither of us could remember where she began and I ended. I want her to hear my heartbeat, thudding irrationally in my chest.

And I am suddenly glad we are here, damp and irritable, in this parking lot, that we have all made it this far. My daughter was born in the hospital; Kitty was born under somebody’s stairs. But we love each other, and we most of the time, we remember to pull our claws.

Ariel Gordon is a Winnipeg writer. Her second collection of poetry, Stowaways (Palimpsest Press), won the 2015 Lansdowne Prize for Poetry. She is currently working on CNF about Winnipeg’s urban forest, which is slated for publication in 2018.

May 1, 2016

The M Word: Ever Since The End, by Christa Couture

This is the fifth in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From previous weeks: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“; “Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self”; “Dear Me, by Nicole Dixon“; “Kerry Clare on Motherhood and Abortion.”

In her essay, “These Are My Children”, Christa Couture introduces readers to her sons, Emmett and Ford, and recounts how she has mothered and related to motherhood since their deaths. Here, she considers what’s changed and what hasn’t in the two years since her essay was published.

*****

Between the time I first wrote “These Are My Children” and the time for final edits before The M Word went to print, the one update I made was to the ages my children would have been, if they were still alive (from six and three to seven and four).

I’m thinking of what’s changed in the time from print to now, and the same update is my first thought: Emmett would be nine, and Ford would be, in a few weeks from now, seven.

When asked to consider what else has changed in this time, I worried that nothing has. Motherhood remains a kind of fixed story for me, one I can still replay from its beginning to end. “The End” was the title of the final blog post where my husband and I kept family and friends updated on Ford’s 14 months of life while he was living. And when I think of my story with my children, “the end” feels almost like the title, not just the last page. I picture it a finished book; I picture that book in a bag that I carry forward into each year of my life.

That hasn’t changed.

I have moved from the city (Vancouver) where my sons’ ashes are interred to Toronto. Thus, I visit that site now, so far, only yearly. When I do, I still place my hand on the shared gravestone, still trace the letters, and still feel comfort in close proximity to their remains, and to the part of my body there.

That hasn’t changed.

When I return to their grave, new gifts have been left on its ledge, from their grandmothers, aunts, father… slow changes to the scenery take place.

In my essay, I had written of the physical record of my children on my own body. The stretch-marked belly remains the same, but the caesarean scar I’ve found comfort in tracing is almost entirely, to the eye, gone, and increasingly fading to the touch. As it fades, the whisper of the ridge of that scar gets quieter: “I am the window he climbed through, into your arms.”

I don’t mind that this fades. And that is a change.

I no longer, as I had written those few years ago, cry daily for them. When I do cry, it is with less distress.

With as much longing, but less panic. This change I am grateful for.

My therapist and I disagreed: he drew a chart, an arc, of grief and pointed to the end, “When is this?”

“Never.”

I argued I will always grieve for my children. He argued it’s an emotion that, like other emotions and like scars, will run its course and fade.

I don’t consider grief negatively. It has slowly become integrated in my body and life, blooming sometimes unexpectedly and otherwise reliably on certain holidays and anniversaries of death and birthdays. Sometimes grief still hurts enough that I gasp for air. Less often, grief still curls me into a ball and I feel blind to anything outside of it. Otherwise, it moves into my chest as a wave and with my hand to my heart and a deep breath, I sway with it until the intensity passes.

I understand better that the intensity passes.

That is a change.

A friend’s baby recently died and I realized that while I knew many bereaved parents, I had met them all after one or both of my sons’ deaths. I had not known it to happen to someone I already knew. I was struck in considering the beginning of what will be a very long journey and in remembering how impossible the first night feels. The first night is the worst one. And then the first week, the first month… how slow and dark time is until the first year when counting starts to become harder to do. How I ached, in early days, for time to pass yet hated that it did—that each day passing only took me further away from my children, putting that event and title “the end” further in the past.

“It’s not that it gets easier, but it does change,” I told this friend, knowing too well that there was nothing I could say that would help.

With her son’s death, I was reminded of having “entered a place in which I could be seen only by those who were themselves recently bereaved,” as described by Joan Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking. I felt, when I first saw my friend, seen in a way I seldom do. I found it comforting, a relief almost, for that part of me that remains hidden (against its need), and then immediately I felt regret: I would rather be lonely in grief considering that understanding can only come through such utter heartbreak.

And, in looking at a beginning after an end, I felt relieved for time passing.

“What place do you go to for strength?” I was recently asked. If time passing is a place, then that is where I have been since I first wrote my essay. I have been writing and singing and crying and moving across the country, and waiting.

And life has changed.

My boys would be nine and seven. I will always count those years and, occasionally, imagine who my boys would be, and would have become.

I will miss them. I will love them.

And that will never change.

**

Christa Couture’s new album is Long Time Leaving. It’s out right now. (Buy it!) She’s currently on a cross-Canada tour.

April 23, 2016

The M Word: Kerry Clare on Motherhood and Abortion

This is the fourth in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From previous weeks: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“; “Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self”; Dear Me, by Nicole Dixon.

**

My essay for The M Word was called “Doubleness Clarifies” (you can read it online here) and I wrote it over four mornings during one week in July 2012 while perched in the rafters of the Wychwood Library—the most terrific vantage point. Harriet was three years old, and it was the first time she’d ever been in childcare—a city-run day-camp managed by a woman I loved who ran the creative play sessions we’ve been attending at the Hillcrest Community Centre since Harriet was one. I’d dropped her off and it was the first time she’d ever been anywhere without me, and I had all this time. Three whole hours. And so I rushed up the street to the library, settled into a carrel, and got to work, headphones plugged into my ears playing Carly Rae Jepsen on repeat.

My essay for The M Word was called “Doubleness Clarifies” (you can read it online here) and I wrote it over four mornings during one week in July 2012 while perched in the rafters of the Wychwood Library—the most terrific vantage point. Harriet was three years old, and it was the first time she’d ever been in childcare—a city-run day-camp managed by a woman I loved who ran the creative play sessions we’ve been attending at the Hillcrest Community Centre since Harriet was one. I’d dropped her off and it was the first time she’d ever been anywhere without me, and I had all this time. Three whole hours. And so I rushed up the street to the library, settled into a carrel, and got to work, headphones plugged into my ears playing Carly Rae Jepsen on repeat.

It was a pivotal time in our family life. Harriet would be starting playschool in September, and I was planning on becoming pregnant again around the same time. The shock of new parenthood had worn off and we’d finally found our groove as a family of three. The pieces of the universe were reassembled and were figuring out the way forward. And now I was putting together an anthology about motherhood, because it seemed I had a knack for telling its truths. And the truth that I wanted to tell about it now was how fundamental choice had been to my whole experience, and how for me the experiences of motherhood and abortion were irrevocably connected.

I’ve written before about learning to talk about my abortion, a process in which my essay from The M Word played an enormous role. “It is only recently, and with a great deal of practise, that I have been able to say ‘abortion’ in conversation without dropping my voice an octave and muttering in order for the word to be nearly inaudible” I wrote in my essay, and that’s the only part of it that seems foreign to me now. I remember writing those lines and contemplating that one day I could possibly end up saying “abortion” in front of an entire room full of people, and wondering whether this was possibly the wisest idea. And yet. It turned out I was braver than I ever thought I could be; and that most people are way less hung up about abortion than you’d ever expect; and that there is nothing more liberating than refusing to feel shame. In understanding that you don’t have to apologize for wanting to know your own soul. Writing that essay, putting my name on it and owning it has taught me a lot about not giving fucks, what it means to be steely, and the kind of example of womanhood I want to set for my daughters. It’s made me into the kind of person I always wanted to be.

It helped, of course, that I was pregnant when the book went out for submission, and that I had a wee baby girl sleeping on my chest throughout the fall of 2013 as I edited the book, and that when the book was launched the following spring, I went to author events wearing the baby on my chest. (The night the book launched at Ben McNally books, I read my piece, and then had to strip down to breastfeed in the fiction section, for I’d chosen a book launch dress with a back zip, perhaps not so wise.) It was easier to stand up in front of a room full of people talking about abortion while holding my cute (albeit very bald, especially in retrospect) baby—I felt her presence shielded me from the possibilities of some criticism, and also legitimized my argument because (as I wrote in my essay): “It is possible that no one more than a mother can truly understand just what it is that a woman who has had an abortion has lost and gained.”

I still think that’s true, though I feel now that the baby was unnecessary. And while she made me feel more comfortable saying the word abortion out loud in public, I don’t wish to imply that any woman has more right to do so than another. But, as I’ve said, for me the experiences of abortion and motherhood are so irrevocably connected. It was the one that allowed me the other.

**

Other happenings in the lives of the women of The M Word:

Myrl Coulter’s latest book is A Year of Days. * Christa Couture’s new album, Long Time Leaving, has just been released. * Saleema Nawaz’s novel, Bone and Bread, was a finalist for CBC Canada Reads 2016 * Alison Pick’s memoir, Between Gods, was a national bestseller and a Globe and Mail Best Book of 2014 *Carrie Snyder’s Girl Runner was shortlisted for the Rogers’ Writers’ Trust Prize * Patricia Storms’ latest picture book is Never Let You Go, which was an OLA Best Bet * Sarah Yi-Mei Tsiang’s The Night Children was published in Fall 2015 * and Priscila Uppal’s latest book is the short story collection, Cover Before Striking.

April 17, 2016

The M Word: Dear Me, by Nicole Dixon

This is the third in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From previous weeks: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“; “Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self”

In her essay in The M Word, Nicole Dixon ruminated on her choice to be child-free, considering the parts of the choice she was uncertain about and and those she knew for sure, one of which was that saying no to kids is not the same as saying no to life, to love. And in this follow-up piece, she finally steps into the sun.

*****

Dear Me,

Dear me! I have to warn you—you’re about to go through two years of hell, but you will get through those two years and on the other side, the side I’m on now, you will be stronger, more hopeful, more at peace than you’ve ever felt. Trust me.

Take solace in your garden, in books, in silence and stillness, in the life you’ve built for yourself in this worn-out town on this beautiful island. You can do it. You’ll get through this. Go for walks. Stare at the ocean. Breathe it in. Feel how big it is, how easily it swallows your sorrow and carries it away on its tides and currents.

Your M Word essay, rereading it, is about choices, and you are about to make plenty. You will quit your shitty job after fighting an abusive boss; you will choose to change the system until you realize how broken it is. You will then choose to turn your back on that system in order to build a new one. You won’t know how to do this or where to begin until one day you will stand in your garden and you will hear it: here. Start where you are. Grow where you are planted. Here—this backyard, this soil, this town, this island. Stay put. Stop moving. Root yourself here. The answer, a dormant plant, will suddenly bloom like spring.

But your hardest choice will be your decision to stop talking to your mom. You will turn to her for support during all your work shit, and she will once again rage at your choices and, finally, after years of fearing your mother, you will choose to step out from her shadow and feel the sun. You too, like your garden after winter, will thrive in the warmth of that sun.

And you will realize, in this choice more than so many others, how much your mother’s abuse has influenced your decision not to have kids. You can’t write about it now, can’t even admit it, but you will. And the darkness she inherited from her mother, the darkness she tried to pass on to you, is a trait you need to nip in the bud. Instead, you will make and nurture another life, other lives, your life. You will grow food in your soil, in a town that has weathered its share of abuses, and you will write about this, you will write and love the land, the earth, and it, unlike your mother, will love you.

Go to your garden. Feel and grow life there. Let it fill you. It will. Believe me, it will.

Be strong in your choices and enjoy the sunlight,

Me

***

Nicole Dixon’s first book was the collection of stories, High-Water Mark. She lives in New Waterford, on Cape Breton Island.

April 10, 2016

The M Word: Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self

This is the second in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From last week: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“.

Heather Birrell’s “Truth, Dare, Double Dare,” opened the collection, a beautiful story about second-chances, forgiveness, and the reality of what it takes to make a family. But the essay’s happy ending would turn out to be the beginning of a more complicated story, which she delineates here.

*****

Promise to Repeat

My sister used to talk to herself when she was about four; at eight, I overheard her chatting away in her bed. She was not discussing the world with an imaginary friend—she was talking to her Self. We knew this, my parents and I, because she used the actual word: ‘Hello, Self,’ she’d say. ‘How you doing today, Self?’ And then she would let her Self know exactly what was up.

In the essay I contributed to The M Word, I talked about my mixed feelings about having a second child—how my first child’s traumatic arrival and aftermath gave me pause. Then I got pregnant (unplanned) and I was so scared. But going ahead with that pregnancy turned out to be a wonderful choice for me and my family. My essay had a happy ending.

But, when The M Word was on the brink of publication, I was struggling through a new crisis; a kind of delayed post-partum depression characterized by Pure OCD that saw me mired in a horrible muck of guilt and fear. Pure OCD sufferers experience repetitive intrusive thoughts that usually involve violent or taboo images. As new (and new-ish) mothers can attest, being so close to fragile new life cannot help but call up thoughts of death. We imagine we will somehow—accidentally or on purpose—hurt our kids. Pure OCD amplifies those thoughts in monstrous, seemingly inescapable ways.

When I was being treated in a Toronto hospital’s short term mental health unit, one of my psychiatric nurses asked me to write a letter to myself. ‘But,’ she said, ‘imagine you are talking to a dear friend in your same situation. We are often much harder on ourselves than we are on our friends.’ The idea was to show myself the compassion that my depression had transformed into criticism and cruel falsehoods. This was a surprisingly easy exercise for me—maybe because I truck in fiction, the words came readily. Writing the letter did not heal me; I didn’t recognize myself in writer or recipient. But the next day, when I re-read what I had written, I felt a measure of comfort. The exercise felt artificial, but the result was something authentic and poignant.

In a blog entry I posted just before The M Word came out (and I use the term blog loosely; I am an infrequent, undisciplined recorder of life when it comes to my online presence), I bemoaned the fact that the essay in some ways did not feel like the ‘truth’ anymore: “I was ashamed that my relationship to motherhood had once again become so challenging, so darkly complex. I felt like a fake.” My truth had changed drastically; my sense of myself as a mother had been shredded by months of despair. The end of my M Word essay is a tempered triumph. And I was feeling far from triumphant.

This past winter, I published an essay in Canadian Notes and Queries as part of their Rereading Series (‘Further Up and Further In: Rereading The Last Battle In the Wake of Mental Illness’). In the essay, I explore how the stories I have absorbed and told myself shape my reality. That essay is one of the many conversations between selves I have been having since I became a mother.

Here is another:

Things I Might Say to My M Word Self

Hello Self. How you doin’? You know, our brain is sailed by some mighty ships. They carry precious cargo. But those ships? They’re vulnerable to our body’s tides, its hormones and adrenal secretions; when they capsize, they send some powerful chemicals sloshing over the sides. Self? You will believe some things about yourself that are not actually true. Or if they are true, they are not true in the everlasting, evil way you are thinking.

Oh, Self, in the next year or so, you will endure some of the hardest, most heartrending days and nights of your life. You will have a moment on a subway platform. Another with some pills. You will not be thinking solution, you will be thinking relief. And I will not tell you suicide is wrong. Because I don’t judge those who wants to end suffering. But I will tell you that what you are feeling will not last forever.

It’s like those nights where the baby will not sleep, and will not sleep, and will never sleep. And then, the baby sleeps. But not every night! Just sometimes, Self. The way forward will be like that.

You check yourself into the mental health unit on your oldest girl’s birthday. This is a detail which will pester you as proof of something. Back up, Self. Recall that you also collected her birthday cake and delivered it home on the way to the hospital. Remember that a mother takes care of herself so that she can take care of her children.

All of this will be hard for your husband to understand. Let him protect the children from this; let him cook for you even when you aren’t hungry. Love and loyalty can take many forms.

Hey Self! Call and email and text all your friends. Say: I need you. Go for walks with them. Watch Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries. Let your mother fold your washing and sort out the kids’ hand-me-down shoes and don’t imagine she is thinking, ‘This sort of couch-loafing behaviour is typical of the selfish, ‘sensitive’ daughter.’ Also: So what if she does think this? Your clothes will be folded and the kids’ shoes sorted.

You are sick. The hard part about this sickness is that they don’t always know which is the right medicine or how long it might take to work. Take the medicine anyway. But don’t shut up if it’s making you sicker. If you can’t speak to the doctors—because this sickness can steal your voice—ask your sister, her voice is strong. Talk therapy is a medicine. Sleep is medicine. And so is time. Do yoga too; you can’t om your way to happiness, but taking deep breaths and rolling around on the floor can’t help but be good for you.

In the hospital, they will ask for your religion. They will ask if you have any hobbies. You will stare at them vacantly. That’s okay; ‘hobbies’ is a dumb word.

Self, I am here in the super-future. We made it.

Heather Birrell’s most recent story collection, Mad Hope, was one of the Globe and Mail’s top 23 Canadian fiction titles in 2012. The Toronto Review of Books called the collection “completely enthralling and profoundly grounded in empathy for the traumas and moments of relief of simply being human.” Winner of the Journey Prize for short fiction and the Edna Staebler Award for creative non-fiction, her work has appeared in many North American journals and anthologies. She currently lives on the Isle of Lewis with her family.

April 3, 2016

The M Word: Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing

This is the first in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.)

Kerry Ryan’s “Confessions of a Dilly-Dallying Shilly-Shallier” was a will-she/won’t-she essay exploring the question of whether or not to take the great leap into motherhood, which makes the prospect of catching up with her more than two years later—it’s actually been even longer since the piece was written—most enticing.

*****

Motherhood: More Wishing and Washing

Confession: by the time I’d finished writing my essay for The M Word, about deciding whether or not I should have a child, I was already pregnant.

Which seems pretty damn decisive for someone who wrote about flip-flopping on the “should we/shouldn’t we?” question.

Writing the essay didn’t exactly help me find an answer, but it did help me understand I had to make a decision. In the end, the decision I made (and ok, my husband was part of it too), was kind of a lame one. I decided we would try.

I was 36 and knew the fertility odds were against me. Plus, my periods were irregular and I figured that didn’t bode well. So, believing it wasn’t likely to work, I decided we’d try for a year and that would be that. We’d have tried, and our life of quiet activities, sleeping until 9:00am on weekends, and taking vacations would continue as usual.

Looking back, I wouldn’t have made it through a year of trying; I’d have chickened out, probably after the first month. Luckily for all of us, my daughter is brave, decisive and seizes the day. I was pregnant after the first try.

At the time, I thought didn’t think: I have made this decision. It was: the decision has been made. (And sometimes: the baby has decided.) But, no matter how, the deciding was complete. What I didn’t realize was this decision was a monster from mythology – decide to have a child and you face 5,000 new decisions. Name. Brand of car seat. Helicopter or free-range parenting. Cloth or disposable. Gender neutral or gender specific.

When you don’t have a newborn, deciding the exact minute a baby should fall asleep or be woken, the position to hold her when she’s nursing, seem inconsequential. When you’re a new mother, every decision is dire. Choose incorrectly and your child will never again sleep in her own bed, will have trust issues, or be otherwise stunted and screwed for life. Even now, whenever I google ideas for trying to get my three-year-old to eat her veggies, I learn that my decision (no dessert until you eat your green beans), guarantees she’ll have an eating disorder when she’s twelve.

Of course, I am not the only decision-maker in the family. My husband and I have equal parenting roles. But in the case of one for and one against, who breaks the tie? The one who is most/least tired/frustrated. The one who is sitting closest. The one who is blaming the other because our toddler is being irrational. So, we’re not always consistent. I’ve read that this will cause our daughter to become a gambling addict, but sometimes we all just need to get back to bed.

As a mother, the decision I have to make most often is laugh or cry? (And, truthfully, sometimes it’s cry or weep uncontrollably?) But, all those little questions have helped me answer the next big one: should we have another? On that, I am resolved.

Kerry Ryan has published two books of poetry, The Sleeping Life (The Muses’ Company, 2008) and Vs. (Anvil, 2010), a finalist for the Acorn-Plantos Award for People’s Poetry. Her poems have appeared in journals and anthologies across Canada and she has a poem forthcoming this month in All We Can Hold: Poems of Motherhood (Sage Hill Press).