January 30, 2018

Boat People, by Sharon Bala

The debut novel by Sharon Bala (who was acclaimed for her short fiction with the award of The Journey Prize last year) is The Boat People, an ambitious, engrossing and absolutely important book that I keep hearing about everywhere—Bala was on The Sunday Edition; reviewed in The Globe & Mail—and for good reason. It’s a book that might be called timely, except that stories like this—of people fleeing war and persecution, chancing everything on survival in a new land, being viewed with suspicion upon arrival, the threat of outsiders and others being manipulated for government propaganda—are as old as stories about people venturing across seas at great peril in search of a better life are. Which is to say: as old as stories themselves. And peoples, and seas.

The debut novel by Sharon Bala (who was acclaimed for her short fiction with the award of The Journey Prize last year) is The Boat People, an ambitious, engrossing and absolutely important book that I keep hearing about everywhere—Bala was on The Sunday Edition; reviewed in The Globe & Mail—and for good reason. It’s a book that might be called timely, except that stories like this—of people fleeing war and persecution, chancing everything on survival in a new land, being viewed with suspicion upon arrival, the threat of outsiders and others being manipulated for government propaganda—are as old as stories about people venturing across seas at great peril in search of a better life are. Which is to say: as old as stories themselves. And peoples, and seas.

Inspired by the 2010 story of a ship of Tamil asylum-seekers arriving in British Columbia, Bala’s story begins with Mahindan, a Tamil mechanic who has lost everything except his young son and has bet everything he has on the chances of finding a new start in Canada. The novel begins with the ship’s interception as it reaches Canada, and follows Mahindan through the process of being imprisoned and separated from his son as months go by and his fate is left in limbo—will he get to stay in Canada, or will be he deported to Sri Lanka where nothing good awaits him. Alternate chapters also take us back through his history, showing us how he went from a happily married man with family, friends and a rich life, awaiting the birth of his first child, to someone with (almost—save for his son) nothing left to lose—the gradual reveal of Mahindan’s backstory makes for compelling, powerful reading.

But Mahindan is not the story’s centre, or not its only one; that this is a story with multiple centres and voices and points of view is an important aspect of its construction. Because there’s never just one centre of a story, and all the best narratives refuse to be contained, overflowing to be resonant in all kinds of surprising ways and flowing into other stories. Like the story of Priya, a second-generation Tamil-Canadian who would just like to finish her placement in corporate law so she can become accredited and begin work in mergers and acquisitions, thank you very much. But the fact of her ethnicity means she’s roped into a position with another lawyer in the company who’s working in refugee law and who overestimates her knowledge in terms of Tamil language and culture to assist him as he supports the Tamil asylum seekers with their refugee claims. Like Mahindan, Priya is somewhere she doesn’t belong, and for a while she resists being involved with the asylum seekers and the war her parents had been so intent on leaving behind them when they arrived in Canada. But eventually, she becomes invested, and the ramifications of this are felt deep within her family.

Like Priya, the story’s third central character has also worked to put the past behind her, a third generation Japanese Canadian called Grace whose hard work in the civil service has been rewarded with a role adjudicating refugee claimants. She begins her new position not long after the Tamils arrive, and political tensions are high, and ever being manipulated by Grace’s former boss and mentor, the Federal Minister for Public Safety whose interests lie in keeping the threat of terrorism high. Meanwhile, Grace’s mother is ailing from Alzheimers and the past and the presents are intermingling in her head, stirring stories of the internment of Japanese-Canadians during World War Two, stories that Grace’s family had been careful never to dwell on. Stories of othering, persecution, public safety threats, racism, and so much terrible history that’s so analogous to what’s going on in the present day.

Bala’s prose is beautiful, the narrative so careful woven, and the shape of the novel itself so terrifically undefined in a way that allows the story to go beyond its limits, to pose questions that don’t necessarily have answers, to unsettle its readers in the most powerful way. There is a didacticism at work, but with a depth and complexity that saves the novel from its few too-earnest moments. Further, a little earnestness is nothing to scoff at, and maybe the author of a book this interesting, original and well-written has earned those moments. Especially since this is such an essential book for Canadians to be reading right now.

January 29, 2018

Encyclopedia of An Ordinary Life

I got Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life out of the library on Friday and devoured it in two days while annoying everybody in my presence because I’d insist on reading passages aloud while they were trying to play Pokemon or read a different book or conduct a conversation. I loved this book so much, for all kinds of reasons, which weren’t necessarily the reasons its author intended the book to be loved when she published it for the first time in 2004. Except for this one: that she’d intended the book as a document of ordinary life at the beginning of the twenty-first century, and at this it succeeds so wildly, but so much so because life in 2004 seems very far away from 2018, where I read this book now. Answering machines, compact discs, and faxes. There is an image of a Yahoo email message, and I’d forgotten what those looked like—the font, the logo, the peculiar line breaks. The internet exists, but you’re not carrying it in your pocket, your purse. It’s still rife with possibilities for human connection, old friends getting in touch, hearing from strangers. The internet in 2004 was bringing us closer together instead of driving us further apart.

I got Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life out of the library on Friday and devoured it in two days while annoying everybody in my presence because I’d insist on reading passages aloud while they were trying to play Pokemon or read a different book or conduct a conversation. I loved this book so much, for all kinds of reasons, which weren’t necessarily the reasons its author intended the book to be loved when she published it for the first time in 2004. Except for this one: that she’d intended the book as a document of ordinary life at the beginning of the twenty-first century, and at this it succeeds so wildly, but so much so because life in 2004 seems very far away from 2018, where I read this book now. Answering machines, compact discs, and faxes. There is an image of a Yahoo email message, and I’d forgotten what those looked like—the font, the logo, the peculiar line breaks. The internet exists, but you’re not carrying it in your pocket, your purse. It’s still rife with possibilities for human connection, old friends getting in touch, hearing from strangers. The internet in 2004 was bringing us closer together instead of driving us further apart.

This book had absolutely nothing in common with Ellen Ullman’s Life in Code, which I finished reading a week ago, except that both had me thinking about the internet’s early days and all that possibility for connection. Rosenthal’s book reminded me of how exciting it was to be on the internet in 2004, the access to offered to worlds I didn’t know existed. The first job I had with an internet connection was at the Financial Post during the summer of 2001, which was the same summer I discovered that there was this fantastic literary culture happening in the world right now—that was the summer I bought White Teeth and A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. 2004 was when I was living in Japan and avidly reading Maud Newton and other book bloggers, and while actually becoming a book blogger still seemed like it was beyond me, living in a world where I had this window onto people doing and thinking and being literary culture was really astounding and transformative to me.

And Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s book gave me that same frisson of inspiration—these glimpses of fascinating people doing cool things. Or even mundane things, which this book is more about, the very point of it. The mundanity of the 2004 internet is also something I missed, as opposed to the YOU WON’T BELIEVE WHAT HAPPENED NEXT… clickbait. Smart people being boring, was the theme of the internet in 2004, or at least the corners of it I frequented. And it’s how I fell in love with blogging, really. The way that smart people being boring illuminated the secret wondrous corners of everyday existence, its various miracles the dancing dust motes (were dust motes actually things that people noticed who weren’t characters in novels).

She also writes a lot about death, which would not be so noticeable were she now, in 2018, not actually dead. It makes this ordinary book much more poignant, extraordinary, necessary, a gift. (See my 2015 post about blogs as “survival gear for our stories.”)

“I shopped for groceries. I stubbed my toe. I danced at a party in college and my dress spun around. I hugged my mother and my father and hoped they would never die. I pulled change from my pocket. I wrote my name with my finger on the cold fogged-up window. I used a dictionary. I had babies. I smelled someone barbecuing down the street. I cried to exhaustion. I got the hiccups. I grew breasts. I counted the tiles in my shower. I hoped something would happen. I had my blood pressure taken. I wrapped my leg around my husband’s leg in bed. I was rude when I shouldn’t have been. I watched the cellist’s bow go up and down, and adored the music he made. I picked at a scab. I wished I was older. I wished I was younger. I loved my children. I loved mayonnaise. I sucked my thumb. I chewed on a blade of grass.

I was here, you see. I was.”

January 23, 2018

Winter, by Ali Smith

I walked through a blizzard to buy Winter a week and a half ago, the new release by Ali Smith that I’ve been looking forward to since rereading Autumn in the autumn. A novel that helped me so much through the political turbulence that was 2017, contemporary events as rendered by literature so that they were just enough at a distance–it was clarifying, and gave me hope. And so it was strange to pick up Winter, the second book in Smith’s seasons sequence, and see that everything wasn’t okay after all. That one book is not going to cure us of what ails us, and the trouble continues through winter, a season during which nature settles down to sleep:

I walked through a blizzard to buy Winter a week and a half ago, the new release by Ali Smith that I’ve been looking forward to since rereading Autumn in the autumn. A novel that helped me so much through the political turbulence that was 2017, contemporary events as rendered by literature so that they were just enough at a distance–it was clarifying, and gave me hope. And so it was strange to pick up Winter, the second book in Smith’s seasons sequence, and see that everything wasn’t okay after all. That one book is not going to cure us of what ails us, and the trouble continues through winter, a season during which nature settles down to sleep:

“God was dead: to begin with. / And romance was dead. Chivalry was dead. Poetry, the novel, painting, they were all dead, and art was dead. Theatre and cinema were both dead. Literature was dead. The book was dead. Modernism, postmodernism, realism, and surrealism were all dead…”

The novel opens the day before Christmas, with Sophia Cleves who is haunted by a disembodied head. Interestingly, this being an Ali Smith book where surrealism is so often present, it doesn’t occur to me until later when we see Sophia through the eyes of other characters, that there is anything unusual about a woman being haunted by a disembodied head. Autumn had the weirdness of people turning into trees, and the head spectre is the strangeness of Winter, and usually these are points that would make me want to give up, but so much else makes me go on. Autumn opens with the absurdity of a character’s engagement with a bureaucrat at the passport office, and Winter does a similar trick with Sophia Cleves’ visit to the bank before they close at noon on Christmas Eve—the insanity and banality of these kind of engagements with the state and/or corporation, the robotic interaction between a human being and a person who’s just doing their job—presumably a human being as well.

Sophia Cleves is not the centre of Winter (the dead of?), which is instead her son Arthur, Art. Who writes a blog called Art in Nature, about stepping in puddles and bird sightings. Art who I was all prepared to sympathize with, all set for him to be my hero—and then we realize that as a hero he’s terribly flawed. His furious girlfriend berating him for his lack of engagement with the world around him, for believing he’s doing his part through his blog posts (which are totally made up; Art never leaves the city), and not seeing what’s going on around them. He tells her, “We’re all right… Stop worrying. We’ve enough money, we’ve both got good assured jobs. We’re okay.”

“Forty years of political selfishness…” she continues. Political divides, the rise of fascism, plastic bags, etc. And he dismisses her, all of it. It’s the way it always been, he tells here. These things are cyclic. Whatever, whatever. We’ll be all right. It’s all fine.

I am Art. This revelation occurred to me around page 58. This, and the fact that I’m a climate change denier , which is a revelation I had on Friday when I got in an argument with my dad about why we see robins around in the winter. “It’s totally normal,” I say, because I read it somewhere once. “Climate change,” says my dad. “It’s getting warmer, it’s scary.” And I become a bit hysterical. I don’t want to be scared. I know climate change is real, but I’m not sure what I’m supposed to do about it in my tiny little life, and so to preserve my sanity I cling to signs that everything is normal. For example, about how when I bought this book, I walked through a snowstorm. A blizzard. In the winter. Things are fine.

The story takes place over Christmas at Sophia’s, when Art comes to stay with his girlfriend, who is not his girlfriend (who has just broken up with him due to his political selfishness) but instead a random woman he meets on the street, an immigrant from Croatia via Toronto with a penchant for Shakespeare who is struggling to get by. When they arrive, it becomes clear that Sophia is not okay, and so they call her estranged sister Iris to come and help, Iris the old hippie, who’d protested against nuclear weapons at Greenham Common, Iris who is the living embodiment of another way to face the world, a way that’s different from Sophia and Arthur’s denial—of seeing, of engaging, and doing her part to change the world. Insisting that, via Greenham Common, she really did.

But it’s not as simple as that, of one way being the good way to live, and the other being bad. There is a moment when Iris and Sophia say to each other, “I hate you.” “I hate you.” And then embrace, and lay down together in bed, and there it is, what has to happen. It isn’t easy. It isn’t neat. But somehow these characters, “see its the same play they’re all in, the same world, that they’re all part of the same story.”

That last line a reference to Shakespeare’s Cymbeline (which I’ve never read or seen!), the play that makes Arthur’s not-girlfriend come to England, in fact. “A play about a kingdom subsumed in chaos, lies, powermongering, division and a great deal of poisoning and self-poisoning”…. “I read it and I thought, if this writer from this place can make this mad and bitter mess into this graceful thing it is in the end where the balance comes back and all the lies are revealed and all the losses are compensated, and that’s the place on earth he comes from, that’s the place that made him, then that’s the place where I’m going.”

Art is how we get there, is Smith’s thesis in this novel. Through Shakespeare, yes, but also by seeing what happens when we put real things in fiction—things like Brexit, and the Grenfell Tower fire. What happens to books when we put the world in it is a question that’s addressed in the most wonderful way, Arthur’s not-girlfriend (whose name is Lux) telling the story of an old copy of Shakespeare kept in a library with the imprint of what was once a flower pressed between the pages. “The mark left of the page by what was once the bud of a rose.” She’d called it, “the most beautiful thing I have ever seen… it was a real thing, a thing from the real world.”

Which was exactly what had made Autumn so powerful to me, and otherworldly too in the ways in which it did engage with the world. It was why reading it again in October was such a big deal, to be present in the novel’s moment. It was why it was especially meaningful to keep reading and discover that the Shakespeare play Lux refers to is housed at the Fisher Library here in Toronto, right at the end of my street. Uncanny, isn’t it? The line between life and fiction blurred in the most fascinating fashion.

My favourite thing about Winter was everything, but I especially loved its connections to Autumn, which are lovely, subtle, and so unbelievably perfect. Except I read somewhere that Spring’s not out until 2020, and how am I supposed to wait that long?

January 15, 2018

“The umbrella exists in a state of flux…”

“Nowadays, in a time when most umbrellas aren’t worth the stealing and are tossed aside like sweet wrappers when they fail, umbrella theft and ‘frightful moralities’ have been largely replaced by general indifference. Like pens, plectrums [guitar pick: who knew?], and Tupperware containers, the umbrella often seems an entity that is not owned but exists in a state of flux, travelling from person to person, taken up and left behind according to various states (or absences) of mind. Think of umbrellas doing endless loops on the Circle line, the inevitable bundles in the corner of lost property offices, the umbrellas in the staff room that nobody seems to own, or forgetting which they do own, they are afraid to take one away lest it actually belong to someone else. I would suggest that modern-day umbrella ownership has less to do with a specific object than the category as a whole: one possesses an umbrella, not their umbrella.” -Marion Rankine, Brolliology: A History of the Umbrella in Life and Literature.

“Nowadays, in a time when most umbrellas aren’t worth the stealing and are tossed aside like sweet wrappers when they fail, umbrella theft and ‘frightful moralities’ have been largely replaced by general indifference. Like pens, plectrums [guitar pick: who knew?], and Tupperware containers, the umbrella often seems an entity that is not owned but exists in a state of flux, travelling from person to person, taken up and left behind according to various states (or absences) of mind. Think of umbrellas doing endless loops on the Circle line, the inevitable bundles in the corner of lost property offices, the umbrellas in the staff room that nobody seems to own, or forgetting which they do own, they are afraid to take one away lest it actually belong to someone else. I would suggest that modern-day umbrella ownership has less to do with a specific object than the category as a whole: one possesses an umbrella, not their umbrella.” -Marion Rankine, Brolliology: A History of the Umbrella in Life and Literature.

January 10, 2018

“Be as large as you’d like to be.”

I was all set to write a blog post about how I hurt my elbow on the Christmas holidays because I fell off the couch when I was bound and gagged (this actually happened) but you’re going to have to wait until next week now for that story because I’ve got something on my mind. I was thinking about the fallout from what’s happening regarding Concordia University’s English Department (short version: a man articulated something women have been talking about for years regarding predatory males on the faculty, and then yesterday it was the six o’ clock news), all these conversations about men in positions of power—and then it occurred to me, “What is this ‘power’ we’re talking about?” The power of a part-time job teaching creative writing? The power of a handful of slim books of poetry whose sales total into the hundreds? The power of editing a literary magazine that nobody ever reads unless they’d like to be published by them (which would then permit said reader/writer the power of a publication credit)? If this is what passes for “power,” then we’re sadly impotent, the lot of us.

I was all set to write a blog post about how I hurt my elbow on the Christmas holidays because I fell off the couch when I was bound and gagged (this actually happened) but you’re going to have to wait until next week now for that story because I’ve got something on my mind. I was thinking about the fallout from what’s happening regarding Concordia University’s English Department (short version: a man articulated something women have been talking about for years regarding predatory males on the faculty, and then yesterday it was the six o’ clock news), all these conversations about men in positions of power—and then it occurred to me, “What is this ‘power’ we’re talking about?” The power of a part-time job teaching creative writing? The power of a handful of slim books of poetry whose sales total into the hundreds? The power of editing a literary magazine that nobody ever reads unless they’d like to be published by them (which would then permit said reader/writer the power of a publication credit)? If this is what passes for “power,” then we’re sadly impotent, the lot of us.

Of course, there is power. As a reader and a writer and someone who published a small press book and continues to be grateful to publish in literary journals, I know that there is indeed power in words, poems and stories; that lit mags can be magic; that small independent presses can move mountains; and a slim book that sells a few hundred copies might matter so much. I do not seek to undermine these institutions, systems and networks. I feel fortunate to have benefitted from them, but I also know that their power is in the works themselves, and that it’s a small and subtle thing, a power that can’t be quantified. This real power is also not a thing that can be lorded over others.

But I’m getting away from the point here, which is the ridiculous fact that a slovenly man with a part-time job and magazine imagines himself as having power. That we’re meant to looking up to a guy who churns out books that nobody reads and who is trapped in perpetual adolescence. That eventually that guy is in his fifties, and he’s entertaining the notion that a brilliant young woman might want to have sex with him—where, I would like to know, does a person get a sense of entitlement like that? Because, quite frankly, I would like to go there and get some too.

On Sunday I read an advanced copy (out in March) of Elizabeth Renzetti’s brilliant, generous, biting and moving collection of essays , Shrewed: A Wry and Closely Observed Look at the Lives of Women and Girls. I loved it. I wanted to read passages to my daughters, buy a copy for my mother, and plan to implore everyone I know to pick up a copy. Several essays had me in tears by the end, others made me want to grab a placard and march down the street, my shrill voice exclaiming, Feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist is for me! It’s a beautiful book rich with lessons learned from a few decades on the feminist frontline. And the theme that emerged as I read the essays was of not-enoughness—not enough women on the US Supreme Court, not enough women MPs in Canada’s House of Commons. (Related: why does nobody ever ask how many is enough men? Oh, wait! Me all the time. But never mind. Maybe a man will write a blog post about it and then we can hear about it tomorrow on the news.)

On Sunday I read an advanced copy (out in March) of Elizabeth Renzetti’s brilliant, generous, biting and moving collection of essays , Shrewed: A Wry and Closely Observed Look at the Lives of Women and Girls. I loved it. I wanted to read passages to my daughters, buy a copy for my mother, and plan to implore everyone I know to pick up a copy. Several essays had me in tears by the end, others made me want to grab a placard and march down the street, my shrill voice exclaiming, Feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist is for me! It’s a beautiful book rich with lessons learned from a few decades on the feminist frontline. And the theme that emerged as I read the essays was of not-enoughness—not enough women on the US Supreme Court, not enough women MPs in Canada’s House of Commons. (Related: why does nobody ever ask how many is enough men? Oh, wait! Me all the time. But never mind. Maybe a man will write a blog post about it and then we can hear about it tomorrow on the news.)

And of course, the book is very much about the way that women are made to feel as though they themselves are never enough—not smart enough, pretty enough, assertive enough, friendly enough, small enough, imposing enough, busty enough, thin enough, conforming enough, or original enough. As a woman, there are infinite ways to be faulty. Which is why it’s particularly powerful when Renzetti writes in her final piece, “Size Matters: A Commencement Address”: “Be large. Be as large as you’d like to be. Take up room that is yours. Spread into every crack and corner and wide plain of this magnificent world. Sit with your legs apart on the subway until a man is forced, politely, to ask you to slide over so he can have a seat. Get the dressing on the salad. Get two dressings. Order the ribs on a first date.”

(And then she goes on to write, “Throw away your scale. Stop weighing yourself. Is there ever a reason to know your precise weight? Are you mailing yourself to China? Are you a bag of cocaine?” Oh my gosh, this book…)

There are so many lessons that I’m taking away with this tragedy/debacle at Concordia/the world in general, but here’s the one I am focussing on today: if a slovenly largely unsuccessful middle aged writer can imagine himself a powerful sexual Lothario then it is possible I might actually be enough after all. Even more than. If a fucking imbecile can be President of the United States, there is really not limit for the rest of us sentient beings. If some guy who edits a literary journal is a powerful figure, then I am fucking King Kong with Godzilla riding on my shoulders, and so are you. And from now on we should be that large, and own the power we’re entitled to.

January 8, 2018

What I read on my holidays…

I think it happened the year I spent Christmas reading Hermione Lee’s biography of Penelope Fitzgerald, when the holidays began to seem to me like a fine vessel for reading biographies. With the time and space necessary to become absorbed by books so book and consuming, 500 or so pages most of them, which isn’t a number of pages that one can read in dribs and drabs. I’ve also developed a habit of going offline for a week or so at Christmas, which helps to get books like this done. Last year my Christmas biography project involved books about Claude Monet, Jane Jacobs, and Shirley Jackson, which was wonderful. So I was been looking forward to the holidays this year, stockpiling life stories, and it was a lot of pages, a lot of living, but I read four biographies in the end, biographies of four women who seem disparate at first glance, and there was such pleasure in drawing their stories together and understanding the ways in which their lives and experiences intersect.

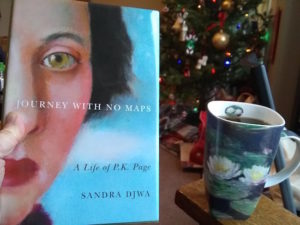

The book I read first was Sandra Djwa’s beautiful award-winning biography of P.K. Page, whose work I’m not very familiar with (although I met her once, in grad school. I can scarcely believe this actually happened. What did I say to her? Hopefully nothing…). Journey With No Maps is the book’s title, which would also be a fitting description for all women whose lives I read about during my holiday, and it was a gorgeously written evocative read. It follows Page through her life and experiences as a writer, a painter, and a diplomatic wife in Australia, Brazil and Mexico. What impressed me most with Page was the way in which she was just incredibly good at everything she set her mind to—she never really had an apprenticeship. Which is not to say that she didn’t grow and develop as an artist, but she was always P.K. Page. She seems to have always been excellent.

The book I read first was Sandra Djwa’s beautiful award-winning biography of P.K. Page, whose work I’m not very familiar with (although I met her once, in grad school. I can scarcely believe this actually happened. What did I say to her? Hopefully nothing…). Journey With No Maps is the book’s title, which would also be a fitting description for all women whose lives I read about during my holiday, and it was a gorgeously written evocative read. It follows Page through her life and experiences as a writer, a painter, and a diplomatic wife in Australia, Brazil and Mexico. What impressed me most with Page was the way in which she was just incredibly good at everything she set her mind to—she never really had an apprenticeship. Which is not to say that she didn’t grow and develop as an artist, but she was always P.K. Page. She seems to have always been excellent.

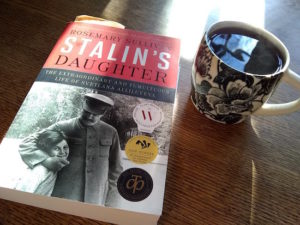

I wasn’t sure what the through lines would be from Page’s life to that of Svetlana Alliluyeva in Stalin’s Daughter, except that Rosemary Sullivan, who wrote the book, appears as a character in Journey With No Maps, which is very cool to consider. Svetlana’s story shows an extreme version of a pattern set out in Page’s biography, that of a woman being defined by her relationships to men. I suppose Svetlana’s is also a story of being in a family with a diplomat—she is paraded out during her father’s dinner with Churchill in 1942—even if the diplomat in question is Stalin. And there is unrequited love in both books—before her marriage, Page was deeply involved in a relationship with a married man that she never entirely got over; Svetlana, sadly, falls passionately in love with one man after another. We learn about Khrushchev’s Thaw, which brought with it political instability—Soviet tanks would crush a Hungarian uprising in 1956, at the same time that P.K. Page’s diplomat husband Arthur Irwin was working with Lester B. Pearson to ease tensions during the Suez Crisis. In 1967, Svetlana would defect to America. Also, Frank Lloyd Wright’s third wife is a bad bad woman, in that she brought Svetlana into an architectural cult and stole all her money. Seriously. The book was such a page-turner, Sullivan is such a wonderful biographer, and Svetlana Alliluyeva was a fascinating woman with literary talent and a fierce intelligence that was so often undermined. I found it interesting to learn how much she resisted all notions of socialism and communism after her experiences of totalitarianism, refusing to enrol her American daughter in public school because she found it anathema that the state should have a role to play in education, or anything. Sometimes its easy to dismiss what happened in the USSR as history, and to be confused by why so many people find state involvement in people’s lives potentially dangerous—Sullivan’s book did well to remind me that there’s some context to that.

I wasn’t sure what the through lines would be from Page’s life to that of Svetlana Alliluyeva in Stalin’s Daughter, except that Rosemary Sullivan, who wrote the book, appears as a character in Journey With No Maps, which is very cool to consider. Svetlana’s story shows an extreme version of a pattern set out in Page’s biography, that of a woman being defined by her relationships to men. I suppose Svetlana’s is also a story of being in a family with a diplomat—she is paraded out during her father’s dinner with Churchill in 1942—even if the diplomat in question is Stalin. And there is unrequited love in both books—before her marriage, Page was deeply involved in a relationship with a married man that she never entirely got over; Svetlana, sadly, falls passionately in love with one man after another. We learn about Khrushchev’s Thaw, which brought with it political instability—Soviet tanks would crush a Hungarian uprising in 1956, at the same time that P.K. Page’s diplomat husband Arthur Irwin was working with Lester B. Pearson to ease tensions during the Suez Crisis. In 1967, Svetlana would defect to America. Also, Frank Lloyd Wright’s third wife is a bad bad woman, in that she brought Svetlana into an architectural cult and stole all her money. Seriously. The book was such a page-turner, Sullivan is such a wonderful biographer, and Svetlana Alliluyeva was a fascinating woman with literary talent and a fierce intelligence that was so often undermined. I found it interesting to learn how much she resisted all notions of socialism and communism after her experiences of totalitarianism, refusing to enrol her American daughter in public school because she found it anathema that the state should have a role to play in education, or anything. Sometimes its easy to dismiss what happened in the USSR as history, and to be confused by why so many people find state involvement in people’s lives potentially dangerous—Sullivan’s book did well to remind me that there’s some context to that.

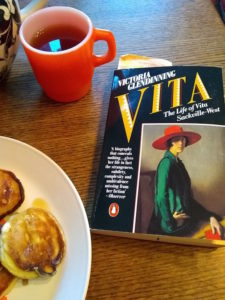

Next up was Victoria Glendinning’s biography of Vita Sackville-West who, as with P.K. Page, I have heard about and read about more often than I have actually read her work. Oh my gosh, this book! I just kept reading allowed my favourite sentences. 1956 factors here as well: “Shortly before they left on a fortnight in France in October—the Suez crisis was raging in England—Vita was stung on the neck by a wasp while giving tea to Megan Lloyd George in the garden.” The whole book is rich with such strange and perfect details, partly because Glendinning is a first class biographer (though Sullivan and Djwa are just as good) but also because she left so much material, her letters and diaries. On page 128 Katherine Mansfield dies, which is 1922—and Mansfield had been a huge influence on P.K. Page in her formative years, and Page carried on a critical dialogue with Mansfield as she read the author’s work. Page was also devastated by Mansfield’s death, though it had taken place more than a decade before Page would learn of it, but she’d been reading Mansfield’s stories in 1930s imagining the author as a kind of contemporary, that she was somewhere out there in the world. Anyway, as per Vita, when Mansfield died, she left a space in the life of Virginia Woolf, a space that would be filled by Vita herself, and Woolf was another great influence on PK Page.

Next up was Victoria Glendinning’s biography of Vita Sackville-West who, as with P.K. Page, I have heard about and read about more often than I have actually read her work. Oh my gosh, this book! I just kept reading allowed my favourite sentences. 1956 factors here as well: “Shortly before they left on a fortnight in France in October—the Suez crisis was raging in England—Vita was stung on the neck by a wasp while giving tea to Megan Lloyd George in the garden.” The whole book is rich with such strange and perfect details, partly because Glendinning is a first class biographer (though Sullivan and Djwa are just as good) but also because she left so much material, her letters and diaries. On page 128 Katherine Mansfield dies, which is 1922—and Mansfield had been a huge influence on P.K. Page in her formative years, and Page carried on a critical dialogue with Mansfield as she read the author’s work. Page was also devastated by Mansfield’s death, though it had taken place more than a decade before Page would learn of it, but she’d been reading Mansfield’s stories in 1930s imagining the author as a kind of contemporary, that she was somewhere out there in the world. Anyway, as per Vita, when Mansfield died, she left a space in the life of Virginia Woolf, a space that would be filled by Vita herself, and Woolf was another great influence on PK Page.

Like Page, Vita was a diplomatic wife, albeit a pretty unorthodox one. “Vita’s prejudices against the diplomatic life were confirmed, though she paid calls, attended and gave luncheons and dinners, as she had in Constantinople; she even gave away the hockey prizes. ‘I don’t like diplomacy, though I do like Persia,’ she told her father.” Later in her life, she was comfortable playing virtually no role in her husband’s diplomatic and political life at all—often to his displeasure. But Vita, like Page and Svetlana, made her own map, for what a daughter, a wife, a woman should be. She rankled at the limits permitted by society to her gender, and was ever resentful that because she was a girl she was not able to inherit her father’s estate and family home by which was tremendously attached and inspired. Though she did manage to buy a castle and live in a tower, so it worked out better for her than it might have for a lot of women. I was fascinated by the process of Vita moving from bohemian renegade to upper class conservative later in her life, as well as her nationalism in spite of her lack of appetite for her husband’s work. It’s such a surprising, but natural trajectory. Like Svetlana, Vita had many many love affairs, but she was the one who left lovers enthralled (and broke their hearts, though they would be forever devoted). Oh, and later in her life, Vita and her husband took to cruises, and when she’d visit Brazil she would find it quite differently than P.K. Page did (who found her experiences there transformative): “I think it is a beastly country and I never want to see it again.”

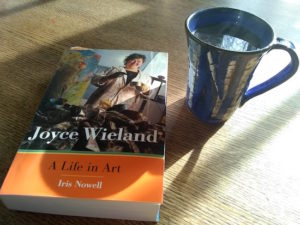

And then finally, another life without maps, that of artist Joyce Wieland, in Iris Nowell’s 2001 biography, Joyce Wieland: A Life in Art. Where there was no mention of the Suez Crisis at all, but Wieland, like Page, would also develop an affinity with Katherine Mansfield. No word on Mansfield and Svetlana—except no!! The evil Olgivanna Lloyd Wright who’d brought Svetlana into a cult and stole her money was the nurse who cared for Mansfield on her death bed, what????? Olgivanna and Mansfield were both pupils of George Gurdjieff, whose work would be meaningful to Wieland throughout her life. (And P.K. Page would become influenced by Gurdjieff through her connection with Leonora Carrington in Mexico. I don’t think Vita Sackville-West had much to do with Gurdjieff at all. I don’t know that she was so concerned with self-development. She had the confidence not to be…)

And then finally, another life without maps, that of artist Joyce Wieland, in Iris Nowell’s 2001 biography, Joyce Wieland: A Life in Art. Where there was no mention of the Suez Crisis at all, but Wieland, like Page, would also develop an affinity with Katherine Mansfield. No word on Mansfield and Svetlana—except no!! The evil Olgivanna Lloyd Wright who’d brought Svetlana into a cult and stole her money was the nurse who cared for Mansfield on her death bed, what????? Olgivanna and Mansfield were both pupils of George Gurdjieff, whose work would be meaningful to Wieland throughout her life. (And P.K. Page would become influenced by Gurdjieff through her connection with Leonora Carrington in Mexico. I don’t think Vita Sackville-West had much to do with Gurdjieff at all. I don’t know that she was so concerned with self-development. She had the confidence not to be…)

Anyway, I saw the Wieland exhibit at the McMichael Gallery in October and really wanted to learn more about her. Of the four women whose books I read, Wieland is the only one who attended a high school I can see from my bedroom (which is a mark of distinction for any life…) Her early life recalls Vita’s mother’s, in its illegitimacy and scandal (her father had left behind a wife and family in his native England) but much more destitute. She would be an orphan by age nine, and spend the rest of her childhood in the care of her older sister and family friends, but it was the Great Depression and not a great time for anybody to be taking in extra children. I loved reading about her experiences growing up in Toronto from the 1930s to the 1950s, the artistic scene in particular. I loved learning about Wieland’s interest in fashion design, and how that informed her art—and how her talent was nurtured during her years at Central Technical School under the tutelage of painter Doris McCarthy.

Once again, Wieland would be defined in relation to a man in her life, the artist Michael Snow—she’d spend a lot of time dismissed as ‘the wife of…”. Interesting to learn that she conceptualized his geese sculptures at the Eatons Centre in Toronto. Interesting too to learn that her art on the Toronto Transit System—which I tweeted about not long ago when we went to see her caribou, lamenting that we don’t have the vision anymore to make public art like that—was hugely controversial when it was installed; seems there never was a golden age of art appreciation. Or that the craftwork in much of her textile art was done by other people who employed, including her talented older system Joan—and she always took care that they got credit. Oh, and the sexism, as per P.K. Page. Unlike the three other women I read about, Wieland did not resist the label of feminist and that was refreshing (especially since all the women in my book stack so exemplified it). Like Page did, Wieland also worked very hard on behalf of Canadian artists and creators and tried to make a space where Canadian works could be celebrated as distinct from their American counterparts. Each of the women I read about on my holidays engaged with nationalism in singular and interesting ways—I’m thinking too of the way that Wieland would come to reevaluate her reverence for Pierre Trudeau, that it was never really reason over passion over all.

But then what kind of life would it be if it ever was? None of these books, nor these lives, would ever have reached the heights they did.

December 6, 2017

My Life With Bob, by Pamela Paul

It’s here! I’m on vacation, in my reading life at least. Which is the way it happens every year sometime in the first half of December when I realize that I’m done. And that for the rest of the month I’ll be reading books just for fun, because I want to, unabashedly and uncritically and for the love of it (including four big books I’ve been saving for the holidays when I take time off-line, biographies of Vita Sackville-West, Svetlana Stalin, P.K. Page, and Joyce Wieland). I’ll be reading books just like I read Pamela Paul’s book, My Life With Bob: Flawed Heroine Keeps Book of Books, Plot Ensues, voraciously and with delight. I loved My Life With Bob, which I bought Friday, started reading Sunday evening, and finished last night whilst sitting on my kitchen table waiting for the pasta to boil.

It’s here! I’m on vacation, in my reading life at least. Which is the way it happens every year sometime in the first half of December when I realize that I’m done. And that for the rest of the month I’ll be reading books just for fun, because I want to, unabashedly and uncritically and for the love of it (including four big books I’ve been saving for the holidays when I take time off-line, biographies of Vita Sackville-West, Svetlana Stalin, P.K. Page, and Joyce Wieland). I’ll be reading books just like I read Pamela Paul’s book, My Life With Bob: Flawed Heroine Keeps Book of Books, Plot Ensues, voraciously and with delight. I loved My Life With Bob, which I bought Friday, started reading Sunday evening, and finished last night whilst sitting on my kitchen table waiting for the pasta to boil.

It’s the kind of book that makes you want to write a book just like it, an autobiography through reading. I would write about reading Tom’s Midnight Garden when my first baby was born, and the night after the second when I sat up breastfeeding and reading Where’d You Go, Bernadette? Reading Joan Didion for the first time on a tram in Hiroshima, which was around the time I started reading Margaret Drabble, the secondhand bookstore in Kobe that’s responsible for my connection with some of the writers I love best. Reading Astonishing Splashes of Colour, by Clare Morrall when I had pneumonia, and Fear of Flying on a plane to London, and The Robber Bride when I was far too young to properly understand anything it could tell me. I really could write an entire book like this—except it probably wouldn’t be as good as Pamela Paul’s.

“Bob” is Paul’s “Book of Books,” a list she’s been maintaining for decades of all the books she’s read. A list without annotations, but who needs annotations, because when she sees the titles they call forth an array of memories and stories. Forcing herself to read the entire Norton Anthology in college, the books through which she learned about New York before she lived there, reading Kafka on an ill-fated high school exchange to France, and her own Catch-22—”the unquenchable yearning to own books—to own books and suck the marrow out of them and then to feel sated rather than hungrier still.” These essays are not necessarily about the books in question, but about what it means to be a book person, to identify as a reader and have literature underline one’s lived experience.

The essays are so incredibly good. They are subtle and unnerving and do precisely what essays are supposed to do, which is to catch their reader off-guard and take her somewhere she wasn’t expecting. As life itself tends to do, and we follow Paul through college, and then post-college travel to Thailand, through the precarity of her early career, and such a stunning sad essay about her short-lived first marriage. Which leads to self-help, of course, and of the time Paul took a writing course with Lucy Grealy (right??) and how she gradually became a writer, as well as a reader. (And oh, do not forget the essay about her relationship with a man who liked the “Flashman” series. Needless to say, it didn’t work out, all this in an essay on the impossibility of getting along with someone whose books you do not like.) And then the essays on reading with her children, and the one on her father’s death and Edward St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose books, which don’t have so much to do with one another except that books are not so simple and so his death and the books become intertwined.

“Ultimately, the line between writer and reader blurs. Where, after all, does the story one person puts down on the page end and the person who reads those pages and makes them her own begin? To whom do books belong? The books we read and the books we write are ours and not ours. They’re also theirs.”

And as I begin my reading holidays, I’m quite ecstatic that this one is mine.

December 5, 2017

Short Story Splendour

Things Not to Do, by Jessica Westhead

Things Not to Do, by Jessica Westhead

I still remember my first Jessica Westhead short story, the title story from what would become her debut collection, And Also Sharks. It was 2012 at the Pivot Reading Series and I was sitting at the bar, and was enthralled: this was a voice like no other. A character whose voice is the light in her darkness, the force and will of it. I loved that entire book, and Westhead’s latest collection does not disappoint those of us who’ve been waiting for it. From Judy who has been working on her assertiveness, to the wedding DJ and Justin Bieber’s dad, and these stories are sad, funny and so quietly and powerfully subversive. I loved them.

A Bird on Every Tree, by Carol Bruneau

A Bird on Every Tree, by Carol Bruneau

This collection had me with its very first story, “The Race,” in which a disappointed war bride takes her chances in a marathon ocean swim, and as a swim-lit aficionado, I was besotted. The story was a feat of language—such sentences. And it’s not just that all the stories in the collection are that splendidly written, but that they manage to be with such incredible breath—historical fiction with the war bride, and then a nun via Lagos, a new mother in a greenhouse with her baby on her chest, a married couple unmoored in Italy, a mother leaves her grown son in Berlin: “We wake to the news that Osama Bin Laden is dead. My treasure in tow—the cheap, matted repro of Kollwitz’s Sacrifice—we catch our early morning flight to Rome.” Old flames and burning fires, and some stories in which the fire goes out completely. If this book were non-fiction, it would be an encyclopedia, because it’s got the whole wide world inside it.

The Whole Beautiful World, by Melissa Kuipers

The Whole Beautiful World, by Melissa Kuipers

And speaking of the whole word, let’s turn to Melissa Kuipers’ debut collection, which I read over a lovely couple of days in early October. Not all the stories were equally impressive, but those that set the standard were really great. I loved “Mourning Wreath”, a look back at a childhood friendship and this fantastic image of a letter written along the entire length of a roll of tape. Many of the stories take place within small, tight-knit Christian communities where the outside world is viewed with suspicion: the sight of a dead cow and a preacher’s invocation of hell commingle in “The Missionary Game.” I also really liked “Happy All The Time,” which tracks how a reaching college kid turns into a cult leader, and “Mattress Surfing,” worlds colliding when an ultrasound technician contemplates the tiredness of her romance with a air balloon pilot. Memorable and original, these are stories that have stuck with me.

What Can You Do, by Cynthia Flood

What Can You Do, by Cynthia Flood

I knew I was in very good company when I was out for dinner in late September, and we were talking about books, and every single one of us had something admiring to say about the work of Cynthia Flood. At that point I’d just read the first or second of the stories in her latest collection, What Can You Do, a collection I’d been well advised not to barrel through but instead to savour slowly, story by story. In the first story, a vacationing couple try to recreate a memory but find it haunting by disturbing stories in the present. In the second, a woman attending an event alone soon after a break-up takes the most satisfying revenge. And oh my gosh, the rumours of a kindergarten predator in “Wing Nut,” hiding behind a tree: how do we ever discern what is reality? Plus the girl who finds the letter from her dead mother hidden in a desk. I could go on. This isn’t a collection that’s easy to talk about as a whole, but every single one of its parts is worth an entire conversation. I like these stories, and they’re ones that I’ll return to.

November 30, 2017

The Marrow Thieves, by Cherie Dimaline

Do you know what’s NOT very original? Me writing about The Marrow Thieves, by Cherie Dimaline, that’s what. The book that won the OLA White Pine Award, the Governor General’s Award for Young Readers, the big-deal Kirkus Prize, among its many accolades, and has since run out of space on its cover for awards. I first encountered Dimaline at The Festival of Literary Diversity in 2016 on a fantastic panel about faith in literature, and she was so impressive I bought her short story collection A Gentle Habit right after and I really liked it. But even so, I was less inclined to pick up her novel that followed it, because I was all, “YA dystopia, huh? No way.” Partly because of my own genre-biases, it’s true, but also because the world is dark enough: why should we throw a pack of post-apocalyptic teens into the mix?

Do you know what’s NOT very original? Me writing about The Marrow Thieves, by Cherie Dimaline, that’s what. The book that won the OLA White Pine Award, the Governor General’s Award for Young Readers, the big-deal Kirkus Prize, among its many accolades, and has since run out of space on its cover for awards. I first encountered Dimaline at The Festival of Literary Diversity in 2016 on a fantastic panel about faith in literature, and she was so impressive I bought her short story collection A Gentle Habit right after and I really liked it. But even so, I was less inclined to pick up her novel that followed it, because I was all, “YA dystopia, huh? No way.” Partly because of my own genre-biases, it’s true, but also because the world is dark enough: why should we throw a pack of post-apocalyptic teens into the mix?

But we should, actually, as advised by Shelagh Rogers who tweeted, “I am delighted @cherie_dimaline. The Marrow Thieves is billed as YA. I urge A’s to read it!!” And then this fall everywhere I went, people kept asking me, “Have you read it yet?” Until finally, I had no choice but to buy it, and I am so glad I did, because (and you never saw this coming): The Marrow Thieves was amazing!

Although it took me a few pages to settle into it, to get a sense of the shape of the narrative. It’s from the point of view of Frenchie, a 17-year-old who travels through the wilderness of Northern Ontario with a ragtag family of kids and a couple of elders ever on the move to escape the clutches of “the recruiters,” officials who take Indigenous people away to special “schools” where their bone marrows are harvested. The reason? Climate change has sent the environment into turmoil and as a result of the devastation people have lost the ability to dream—except for Indigenous people, whose resilience and connection to the land has enabled them to survive one apocalypse already and whose dream lives are an essential part of their cultures. And so the bone marrow of Indigenous people become coveted, the key to recovering the ability to dream without which people the world over are going mad.

The book begins with Frenchie’s brother being taken by the recruiters, after the boys have already been separated by their parents and the world is a dangerous, toxic place. Using his wiles, as well as his connection to the land and remarkable abilities in hiding and climbing, Frenchie gets away from the recruiters and is eventually found by Miig, who tells Frenchie and the other children who travel with him the story of what has happened to their land and their people, some of this story still speculative to novel’s the reader and much of it historical fact. We follow Miig and Frenchie and the rest of their found-family, learning the often harrowing stories of how many of them came to join the group.

But soon the recruiters are getting closer, and the stakes are getting higher. Three quarters of the way through, this novel becomes so difficult to put down and part of the appeal is that all its darkness is underlined with such abundant joy. The love story between Frenchie and Rose is part of this, as well as the family love between Frenchie and Miig and the other members of their group, and the strength and wisdom they carry on their journey that seem incorruptible. Amidst the YA darkness is the rich spirituality of the novel and its sense that some things—love, not least among them—are inconvertible. That life and love and land are worth surviving for.

And the third last page! The third last page! It had me audibly gasping like a, well, like a grown up devouring a YA dystopian novel in all its incredible goodness. I still can’t get over that third last page, and what it leads to. I loved this book, and urge you to pick it up if you haven’t read it yet.

November 27, 2017

Your Heart is the Size of a Fist, by Martina Scholtens

After a few days stuck in a reading rut, I knew I was probably going to enjoy Your Heart is the Size of a Fist, by Martina Scholtens MD. I’d flipped through it and supposed this was a collection of vignettes about a doctor’s experience working with patients at a Vancouver refugee clinic, a timely topic with the arrival of thousands of Syrian refugees in Canada over the last two years, and considering that our previous Federal government had seen fit to cut refugee healthcare—a decision that was reversed when the Liberal government restored benefits in 2016. A few passages jumped out at me—there was a bit about Canadian sponsors and infantilization of the refugee families they’d supported, which is something I’ve been thinking about a lot, the complexity of those relationships. This would be a book I’d find interesting, I knew.

After a few days stuck in a reading rut, I knew I was probably going to enjoy Your Heart is the Size of a Fist, by Martina Scholtens MD. I’d flipped through it and supposed this was a collection of vignettes about a doctor’s experience working with patients at a Vancouver refugee clinic, a timely topic with the arrival of thousands of Syrian refugees in Canada over the last two years, and considering that our previous Federal government had seen fit to cut refugee healthcare—a decision that was reversed when the Liberal government restored benefits in 2016. A few passages jumped out at me—there was a bit about Canadian sponsors and infantilization of the refugee families they’d supported, which is something I’ve been thinking about a lot, the complexity of those relationships. This would be a book I’d find interesting, I knew.

What I was not anticipating was that I’d be so compelled by the work as literature, for its shape as a memoir, the glimmer of its prose, and for its depth and richness as memoir. These are not just stories of Scholtens’ patients, the story of her work, its challenges and contradiction, its joys and satisfactions. The book is framed by Scholtens’ engagement with a family newly arrived from Iraq (although, as she writes in her preface, her patients in the book are composites of actual people for privacy concerns) and also by her own family life as she suffers a miscarriage and then later becomes pregnant again, giving birth to her fourth child. She counsels the Haddad family through their health concerns (PTSD among them), works to diagnose their son’s developmental problems, talks to their teenage daughter about sexual health, and gives the girl’s mother advice about how to get pregnant all the while being wary of the many health risks involved. Along with this family, we are shown glimpses into Scholtens’ relationships with other patients, from Kenya, Myanmar, Syria and Iraq.

It is with Scholtens’ own pregnancy loss and the profound way in which her own healthcare provider is present for her that she has a revelation about the role she plays in her patients’ lives. Previously, she’d felt uncomfortable with their profound gratitude toward her when she felt as though she wasn’t really providing anything, or certainly only providing to piecemeal solutions to the problems they were working to overcome in their lives. But she comes to understand the value of a physician just to bear witness and listen. She comes to understand too that while the gifts her patients bring for her, for example, might make her uncomfortable, her patients are seeking to balance a relationship in which they feel profoundly indebted. Or else gift-giving is an important cultural touchstone for that particular patient—and there funny and lovely anecdotes depicting these interactions.

Bearing witness is no small thing though, and Scholtens writes beautifully about her own struggles. What does it do to one’s spirituality and notions of God and good and evil, to see evidence of the harm and trauma that people can inflict on others? How does she reconcile her own comfortable life in contrast to the poverty and social isolation of the people she cares for? How to balance the demands of her job with her own mental health and general wellbeing—not to mention the demands of caring for four children? How to bridge cultural gaps without undermining the essential nature of cultural identity and religion?

Your Heart is the Size of Your Fist becomes a story of how a doctor learns from her patients the answers to all these questions, or at least discerns clues as to the direction to go in search of answers. To say that it’s an uplifting and breezy read should not undermine the spiritual weight of Scholtens’ story and its importance—but hopefully it will compel you to read it.