April 10, 2018

A Dangerous Crossing, by Ausma Zehanant Khan

Everything is a little too close to home in Ausma Zehanat Khan’s latest mystery, A Dangerous Crossing. Inspector Esa Khattak’s best friend Nathan Clare’s sister Audrey has gone missing from the migrant camp in Lesvos where she’d been working for a Canadian non-profit, fast-tracking Syrian refugees to Canada. An Interpol officer is dead and Audrey has disappeared—is she responsible for the murder? Where has she gone? Has she been taken, and by who? And how to account for the discrepancies between Audrey’s official business with the non-profit and what she’s actually been up to?

Everything is a little too close to home in Ausma Zehanat Khan’s latest mystery, A Dangerous Crossing. Inspector Esa Khattak’s best friend Nathan Clare’s sister Audrey has gone missing from the migrant camp in Lesvos where she’d been working for a Canadian non-profit, fast-tracking Syrian refugees to Canada. An Interpol officer is dead and Audrey has disappeared—is she responsible for the murder? Where has she gone? Has she been taken, and by who? And how to account for the discrepancies between Audrey’s official business with the non-profit and what she’s actually been up to?

To stave off a diplomatic nightmare, Esa and Rachel fly to Greece and are overwhelmed by what they find there—the enormity of the need, the scarcity of resources, the boatloads of people that continue to arrive on the shores. And the people themselves, each with their own stories, people who balk at being considered part of a refugee “crisis.” Words matter, as Khan makes clear throughout the novel. What is the crisis? Are these migrants or refugees? All of these questions (and the story of the refugees in general) distracting from the matter at the heart of it all, the brutal war and tyranny in Syria, torture and war crimes, the devastation from which people are running for their lives. The details are hard to stomach, but necessary to witness, especially to understand their ramifications. Which manifest in so many ways—human trafficking, the rise of violent nationalism, the arrival of refugees, PTSD, corruption and abuse of power, and more.

This is a powerful and moving story that manages to weave these huge narrative strands together in a believable fashion. I had a harder time with the personal stories of Esa, Rachel and Nate—part of it is that Esa and Rachel are both characters who seem to be at a remove, and so these rare glimpses into their souls can sometimes only reveal a stranger. (Oh, Esa! How could you!!) I also got the feeling that this was a transitional novel in terms of the characters’ personal lives and some of the scenes in the middle felt like work to get to arrival, but I really like where they end up—Rachel’s revelations about her feelings towards Esa in particular was really beautiful.

Khan is a gorgeous writer, her prose is backed up by her background in international human rights law, and—though her previous novels suggest it this one definitely confirms it—she can craft a detective story up there with the best of them.

April 3, 2018

“Enlarge and Complicate”

I’ve been reading so much lately—book after book, and while my backlist TBR shelf is suffering from neglect (I have a Penelope Mortimer book waiting, for heaven’s sake…) the wonders of Spring 2018 Canadian books are overwhelmingly good. I’m averaging about three books a week, and it’s still not enough for me to read everything I want to read, which is why I cannot be entirely despondent about the state of “CanLit” even as its politics give us very good reason to wonder what the point is. But the point, of course, is the books, and the books are excellent, and I’m also grateful that so many of these excellent books are written by people of colour (even if I think it’s a bit of a dry season for books by Indigenous writers, Terese Marie Mailhot’s amazing memoir Heart Berries—which I read last week—the only one that’s really on my radar…)

I’ve been reading so much lately—book after book, and while my backlist TBR shelf is suffering from neglect (I have a Penelope Mortimer book waiting, for heaven’s sake…) the wonders of Spring 2018 Canadian books are overwhelmingly good. I’m averaging about three books a week, and it’s still not enough for me to read everything I want to read, which is why I cannot be entirely despondent about the state of “CanLit” even as its politics give us very good reason to wonder what the point is. But the point, of course, is the books, and the books are excellent, and I’m also grateful that so many of these excellent books are written by people of colour (even if I think it’s a bit of a dry season for books by Indigenous writers, Terese Marie Mailhot’s amazing memoir Heart Berries—which I read last week—the only one that’s really on my radar…)

Anyway one book that stands out even though I read it in a whirlwind in early February (to see if it would be a good addition to the 49thShelf.com “#MeToo Reading List” I made; and hey, it was!) was The Red Word, by Sarah Henstra. It was a mindfuck of a book, such hard work, but also impossible to put down, incredibly compelling, a novel about campus culture, sexual violence, culpability, and the meaning of justice. I had the opportunity to ask Sarah some questions about her book over at 49th Shelf, and her answers were fantastic:

49th Shelf: The Red Word is hard work, in the very best way. It complicates binaries, messes with our notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice. Why was it important for you that this book not be a polemic? And was it difficult to make that happen?

Sarah Henstra: The Red Word tackles complicated subject matter, so I felt it warranted a complicated treatment. My decision to have the Raghurst women stage their attack on the fraternity the way they do arose from two separate impulses I felt as a writer, one having to do with what story I was telling and the other with how to tell the story. In the 1990s on college campuses (as elsewhere), the dice were so loaded against the survivors of sexual violence that justice seemed an impossible prospect. The young women in the novel are so frustrated with inequality, so sick of recording and reacting to the misdeeds of the frat boys without seeing any real changes, that they believe this is the only way forward, and they’re convinced—for a while, at least—that the ends will justify the means.

In terms of the story’s structure, I sought a scenario that would leave open the maximum number of possible resolutions in order to allow readers to remain curious and to consider a wide variety of perspectives and points of view. After all, it’s the unexpected consequences of the plot—those surprise moments when events blow up way past the characters’ intentions—that keep us reading.

I’ve always liked Susan Sontag’s assertion (in her 2004 lecture on South African Novel laureate Nadine Gordimer) that good novelists are “moral agents” precisely because the stories they tell don’t moralize but instead “enlarge and complicate—and, therefore, improve—our sympathies. They educate our capacity for moral judgment.” It definitely took this book longer to find a publisher because of its lack of a “redemptive” or “hopeful” resolution, though. “What is the takeaway here for feminism?” one editor asked me. Luckily, the editors who strongly connected with it (Amy Hundley at Grove, Susan Renouf at ECW) loved it precisely for its refusal to come down cleanly on one side of the conflict.

March 29, 2018

The Apocalypse of Morgan Turner, by Jennifer Quist

I listened to a wonderful segment on CBC’s The Current this morning about the necessity of changing our relationship with death, of re-familiarizing death as a concept and inventing (or rediscovering) rituals for it to be woven into the fabric of our lives. This same directive has also been the force behind Jennifer Quist’s first two novels, both of which were odd and oddly compelling, books that particularly preoccupied with death and the macabre. I read both of them and found them well-written and remarkable, but never quite knew what to make of them as a reader, let alone a reviewer. However Quist’s third novel, The Apocalypse of Morgan Turner, is the one I finally feel as though I’ve got a handle on—and I’m grateful to her publisher, Linda Leith Publishing, for their investment in voices who are a little outside the ordinary, in writers who are daring to do something different.

I listened to a wonderful segment on CBC’s The Current this morning about the necessity of changing our relationship with death, of re-familiarizing death as a concept and inventing (or rediscovering) rituals for it to be woven into the fabric of our lives. This same directive has also been the force behind Jennifer Quist’s first two novels, both of which were odd and oddly compelling, books that particularly preoccupied with death and the macabre. I read both of them and found them well-written and remarkable, but never quite knew what to make of them as a reader, let alone a reviewer. However Quist’s third novel, The Apocalypse of Morgan Turner, is the one I finally feel as though I’ve got a handle on—and I’m grateful to her publisher, Linda Leith Publishing, for their investment in voices who are a little outside the ordinary, in writers who are daring to do something different.

And of course, The Apocalypse of Morgan Turner is also about death, but the lens is wider here, and so too is the story’s resonance. Whereas Quist’s previous novels were concentrated on individual families and their esoteric habits and rituals, The Apocalypse… involves two very families, the interactions and intersections between those two families, and also with other individuals with a wide range of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. At the centre of the novel is Morgan Turner herself, three years after the brutal murder of her sister Tricia. Three years after so that some of the shock and trauma of such a violent crime has faded away, and the narrative can consume itself with ideas beyond conventional grief and loss. Important too: Morgan and Tricia were not especially close, and her sister’s death has not left a gaping hole in Morgan’s life. Also, Morgan Turner is not a person who demands a lot of life or the world anyway—she’s content enough taking the bus every day to her job washing dishes in a fast food restaurant. So that she might not rail at the universe for all its injustices the way another character would who’d see herself at that universe’s centre.

Which is not to say that Morgan isn’t questioning: how does a person begin to move on after such a tragedy? The question particularly relevant as the trial for Tricia’s accused killer is coming up, and he’s planning to plead that he’s not criminally responsible for what happened to him. Which, naturally, is upsetting for the entire Turner family, although they all handle it in different ways. Morgan’s parents, Marc and Sheila, are divorced, and Marc has made himself a (rather self-serving) media sensation for his forgiveness of his daughter’s killer—and Quist’s black humour is apparent here with her poignant portrayal of the pretty ridiculous Marc, as compared to his ex-wife:

Sheila’s anger is always raw and steaming, irresolvable. Her story is tenacity‚ chasing Finnemore toward a crushing, punishing destiny she has already publicly denounced as insufficient. When she and Marc divided up their archetypes, he chose the wrong side. His story of cooling and moving on—a loud, public claim of letting go. Soon, he will have to stop talking about it, stop posing for it, stop pleading for it, and do it.

Morgan’s feelings manifest in stranger ways—she becomes preoccupied with horror films, she ones she remembers from during the brief time her sister had been a film studies major before she dropped out of school. She also becomes obsessed with the abattoir where her brother works, and ends up getting job in the factory kitchen, where she connects with Chinese colleagues over an obsession with Korean soap operas. Meanwhile, she’s attending meetings with the crown attorney who’ll be prosecuting the case, not her lawyer, no. The family doesn’t have a lawyer, of course, or a real place in this process (which is part of the reason that Morgan doesn’t know what to do). The lawyer prosecuting the case has a family of his own, a sister Morgan encounters one day while she’s clearing tables in the restaurant where she works. This is Gillian, “a Mormon do-gooder,” who pops in and out of Morgan’s life after that. And Gillian’s other brother, Paul, who is schizophrenic and who is grappling with his own problems with the legal system. And together, all of these characters provide Morgan with the spiritual scaffolding to process what happened to her sister and her family, and to begin to move on with her life.

I loved this book. Quist’s narratives are always rich and compelling, and this latest novel is no exception. It’s sad and brutal, but also sweet and funny, and all its characters are so real. It also becomes such a page turner as the story progresses, the trial nearing its end, Morgan’s desperate attempt to be there for the verdict—there is so much tension. We’re also been privy to the lawyer working into the early hours of morning on the case, and how high are the stakes, and what does it all mean? And where do we find that meaning, which is the novel’s central question, and Morgan Turner’s revelation. Revelation being another word for “apocalypse,” which is only just about destruction and devastation as we understand it in the pop-cultural sense, but instead what is revealed by devastation, a divine truth. Or truths, maybe, which is what happens here with the generosity of the people Morgan meets, with what they show her, unwittingly, or otherwise, about this awful, amazing, brutal, beautiful world.

March 27, 2018

Catch My Drift, by Genevieve Scott

I was always going to have an affinity for Genevieve Scott’s debut novel, Catch My Drift. Its protagonist, Cara, is nearly my exact contemporary, and I also have a strong fascination with the 1970s’ Toronto that brought my parents together and delivered us all into the world I remember from my childhood. I’m also kind of crazy about Swim-Lit, although Catch My Drift is only really pool-centric in the first chapter, which is when Cara’s mother Lorna is a on the cusp of trying out for the Varsity swim team at the University of Toronto. It’s 1975, and swimming is her entire identity, her whole life. Which has already been rocked by the end of a romance and a car accident in which her knees were injured, undermining her swimming potential. It’s summer and she’s training at the pool where her roommate is a lifeguard, sneaking in for laps just before closing. But when it comes time to prove herself, Lorna flinches, setting in motion the rest of her life, for better or for worse.

I was always going to have an affinity for Genevieve Scott’s debut novel, Catch My Drift. Its protagonist, Cara, is nearly my exact contemporary, and I also have a strong fascination with the 1970s’ Toronto that brought my parents together and delivered us all into the world I remember from my childhood. I’m also kind of crazy about Swim-Lit, although Catch My Drift is only really pool-centric in the first chapter, which is when Cara’s mother Lorna is a on the cusp of trying out for the Varsity swim team at the University of Toronto. It’s 1975, and swimming is her entire identity, her whole life. Which has already been rocked by the end of a romance and a car accident in which her knees were injured, undermining her swimming potential. It’s summer and she’s training at the pool where her roommate is a lifeguard, sneaking in for laps just before closing. But when it comes time to prove herself, Lorna flinches, setting in motion the rest of her life, for better or for worse.

We meet Cara in the next chapter, 1987, nine-years-old, and see Lorna now, no longer a woman on the cusp of her life, but instead a mom. A mom who’s dealing with an unreliable partner, the domestic demands of parenthood, and the consequences of a life she made that hasn’t turned out like she might have imagined. But all this is on the periphery—the narrative is filtered through the perspective of Cara, for whom her mother doesn’t really exist as a character in her own right yet. And so the story goes, moving back and forth from mother to daughter as the years go on, as Cara develops into her own person and Lorna reconciles with her own choices, a life with a lot she is proud of. Although at this point, we’re still seeing her through the disdainful eyes of her teenage daughter, who is grappling with her own questions about the kind of woman she wants to be, so it’s complicated. But it is the subtle softening of Cara’s understanding of her mother, her own emerging sympathy for her that is my favourite part of the novel, and culminates in an ending I feared would be heartbreaking but ended up being perfect and beautiful.

Not everything is subtle in Catch My Drift. Some secondary characters border on caricature. This is a novel composed of pieces and the shape of it all is a little unwieldy. In some places it reads like a first novel…but the more I read, the more assured I was by the project, and the more the story appealed to me beyond simple nostalgia. Partly because it becomes clear that nostalgia is a point the novel hangs on—what do we remember and why? What version of reality are those memories made of? How did we get from here to there? What are the consequences of our actions, both in our own destinies and in the lives of others? Because the answers are wondrous and far-reaching, even in the most ordinary lives.

March 26, 2018

A One-Handed Novel, by Kim Clark

It’s a quandary, certainly, and not one I’ve ever encountered in fiction before. Melanie Farrell has already done most of the things you read about in novels—she’s come of age, gotten married, been divorced, confronted a life-changing diagnosis (Multiple Sclerosis) etc. etc., but now in Kim Clark’s A One-Handed Novel, her doctor delivers her some devastating news. Her disease is progressing (not news) and a neurological test has revealed she has just six orgasms left. Six! And she’s already spent once since the test, she realizes—what to do? And so begins her journey to use those remaining orgasms to their best and fullest potential, to make each one count. But then best intentions have always been Melanie’s downfall—witness the items on her Twelve Days of Christmas list, which are most consistently “liquor” and “guilt”. With hilarity and so much heart, Clark takes her reader on Melanie’s journey to make the most of her remaining orgasms. A comic novel about MS—who would have thought it? But it’s also about sex, about coming to terms with one’s bodily limitations, and about friendship, money, hope, and community. It’s not so narratively taut—a third of the way through the remaining orgasms conceit is put aside while Melanie travels to Costa Rica for the expensive and controversial “liberation therapy” which fails to deliver the results she is looking for. Clark also relies too much on humour to carry the story, poignant moments rushed by to arrive at a wisecrack. The end of the novel also crosses the line beyond ridiculous and I feel like some meaning gets lost in the absurdity…and yet. And yet, how can you criticize someone’s narrative trajectory in their comic novel about MS? I feel like the humour and absurdity is a form of resistance, against the cliches and inspiration readers are often seeking in memoirs of disability and illness. The narrative’s all-over-the-placecess too is appropriate for a story of a progressive disease, with the arrival of symptoms where they’re least expected, some improvement, a step forward and two steps back, and then the possibilities that arrive with wild hope, that necessary wild hope—maybe indeed liberation therapy in Costa Rica will produce a miraculous cure? A progressive illness is not a straight line, but neither is any life experience, and so to expect a story to conform to such neatness is an awful lot to ask. I really enjoyed this book, its humour, its wildness, and its point of view—and my appreciation for it was underlined by an understanding of Clark’s background as a playwright. Because while this not the most perfectly shaped novel I have ever read, Clark has got her character’s voice (first person) so exactly perfect. It’s a voice for a monologue, a voice that begs to be performed, funny, generous and wise, and it’s a voice that echoes in the reader’s mind long after the novel is finished.

It’s a quandary, certainly, and not one I’ve ever encountered in fiction before. Melanie Farrell has already done most of the things you read about in novels—she’s come of age, gotten married, been divorced, confronted a life-changing diagnosis (Multiple Sclerosis) etc. etc., but now in Kim Clark’s A One-Handed Novel, her doctor delivers her some devastating news. Her disease is progressing (not news) and a neurological test has revealed she has just six orgasms left. Six! And she’s already spent once since the test, she realizes—what to do? And so begins her journey to use those remaining orgasms to their best and fullest potential, to make each one count. But then best intentions have always been Melanie’s downfall—witness the items on her Twelve Days of Christmas list, which are most consistently “liquor” and “guilt”. With hilarity and so much heart, Clark takes her reader on Melanie’s journey to make the most of her remaining orgasms. A comic novel about MS—who would have thought it? But it’s also about sex, about coming to terms with one’s bodily limitations, and about friendship, money, hope, and community. It’s not so narratively taut—a third of the way through the remaining orgasms conceit is put aside while Melanie travels to Costa Rica for the expensive and controversial “liberation therapy” which fails to deliver the results she is looking for. Clark also relies too much on humour to carry the story, poignant moments rushed by to arrive at a wisecrack. The end of the novel also crosses the line beyond ridiculous and I feel like some meaning gets lost in the absurdity…and yet. And yet, how can you criticize someone’s narrative trajectory in their comic novel about MS? I feel like the humour and absurdity is a form of resistance, against the cliches and inspiration readers are often seeking in memoirs of disability and illness. The narrative’s all-over-the-placecess too is appropriate for a story of a progressive disease, with the arrival of symptoms where they’re least expected, some improvement, a step forward and two steps back, and then the possibilities that arrive with wild hope, that necessary wild hope—maybe indeed liberation therapy in Costa Rica will produce a miraculous cure? A progressive illness is not a straight line, but neither is any life experience, and so to expect a story to conform to such neatness is an awful lot to ask. I really enjoyed this book, its humour, its wildness, and its point of view—and my appreciation for it was underlined by an understanding of Clark’s background as a playwright. Because while this not the most perfectly shaped novel I have ever read, Clark has got her character’s voice (first person) so exactly perfect. It’s a voice for a monologue, a voice that begs to be performed, funny, generous and wise, and it’s a voice that echoes in the reader’s mind long after the novel is finished.

March 20, 2018

New books by Elisabeth de Mariaffi and Nathan Ripley

Hysteria, by Elisabeth de Mariaffi

The week I was reading Hysteria, I was a bit all over the place, and in the beginning was having some trouble following the novel. “Is it you or me?” I wondered, which was kind of fitting, because the protagonist is wondering the same thing about everybody around her. The novel wasn’t what I’d been expecting either—from the jacket copy, I’d been picturing Gone Girl, domestic suspense, and girls on trains. But then I began reading and found myself in the land of Betty Draper—although not before a prologue with fairy tale elements, a girl lost in the woods and even in the land of Grimms, not far from Dresden near the end of World War Two. But de Mariaffi’s Betty and the girl in the woods turn out to be the same person, just a decade apart. Heike, rescued from a Swiss convent by her American doctor husband—she’d been for a time his patient—who has delivered her to America, and now to a lake house in New York State near the mental hospital where he is working and where Heike will spend the summer caring for their four-year-old son. All of which isn’t to say that I wasn’t enjoying the book—I adored de Mariaffi’s previous novel, The Devil You Know—but instead that I found it disorienting, and I soon realized that I was supposed to. Because Heike, like I felt as a reader, is also out of place and unable to trust her own senses—she’s fragile from her wartime trauma and her husband keeps giving her pills that make her dozy. So that when she starts seeing ghostly images of a young girl, it generally seems in keeping with the spirit of things. And then her son disappears, and Heike’s husband won’t tell her where he’s gone, and it’s around this point when Heike’s agency becomes apparent and she takes up with a television writer inspired by the creator of The Twilight Zone, and I was thinking about The Turn of the Screw and the mechanics of ghost stories. Hysteria was excellent, even before I found my feet, and now I want to go back and find my way through it again.

*

Find You in the Dark, by Nathan Ripley

Find You in the Dark, by Nathan Ripley

Once you’re reading enough books about murder, your standards for gruesomeness start to change, so that all of the sudden you’re on the radio saying, “Oh, yeah, it’s a book about a man obsessed with serial killers and digging up the long-lost remains of their unclaimed victims.” Like that isn’t weird at all, right? Which is the point of Find You in the Dark, by Ripley (a pseudonym for the award-winning Naben Ruthnum), the way that it’s easy to be swayed by the protagonist, Martin Reese, a retired tech millionaire whose hobby just happens to be unearthing remains. Plus, he’s married to the sister of a woman who disappeared twenty years ago, and begins to slip comments about nasty deeds committed in his youth. Is Martin—loving husband and father, albeit a bit weird—really such an ordinary guy? The reader begins to discern that his intentions aren’t as honourable as he’d have us suppose. And we aren’t the only ones who are suspicious, because someone else has found out what he’s up to and there’s a fresh body buried in a decades-old grave, and Martin Reese’s carefully constructed reality is seriously under threat. There’s also a kick-ass police detective who is smarter than he is, so Martin has to figure out something fast. But do we want him to? Is he a good guy or bad? That moral ambiguity is one of the most compelling parts of the novel, whose creepiest aspect turns out not to be the unearthed bodies, but instead the experience of being made to feel so sympathetic to such a messed up mind.

March 13, 2018

More Fun at English Bookshops

That we only visited three bookshops seems a bit paltry, although a little less so when you consider we were only in England for six days. My only regret is that this time we didn’t get to visit a bookshop on a boat where we were fed Victoria Sponge Cake, but perhaps that can only happen so often in a lifetime. Our trip to England was a little more local this time, focussed on Lancaster where we’d rented a house for a week. A house that came with a wall full of books, which seemed like a good omen—”But don’t let this make you think we don’t have to go to all the bookshops,” I reminded everybody.

We’d actually visited our first bookshop before we even got to England, because I like the idea of travelling to England with no books, instead picking them up on my travels. Which is pretty risky, actually, considering the decimation of book selection at the Pearson International Airport where there are no longer actual bookshops, and instead a small display of books on display alongside bottles of Tylenol and electrical volt adapters. But I found a couple of titles that interested me, ultimately deciding on Anatomy of a Scandal, by Sarah Vaughan, the story of a political wife whose life comes apart when her husband is accused of rape. A timely book, and it was interesting, but spoiled for me by a “twist” that made this very fathomable story a little bit less so. Which meant that I was all too ready to buy another book at our first English bookshop, Waterstones in Lancaster.

We’d actually visited our first bookshop before we even got to England, because I like the idea of travelling to England with no books, instead picking them up on my travels. Which is pretty risky, actually, considering the decimation of book selection at the Pearson International Airport where there are no longer actual bookshops, and instead a small display of books on display alongside bottles of Tylenol and electrical volt adapters. But I found a couple of titles that interested me, ultimately deciding on Anatomy of a Scandal, by Sarah Vaughan, the story of a political wife whose life comes apart when her husband is accused of rape. A timely book, and it was interesting, but spoiled for me by a “twist” that made this very fathomable story a little bit less so. Which meant that I was all too ready to buy another book at our first English bookshop, Waterstones in Lancaster.

I love the Waterstones in Lancaster. My heart belongs to indie bookshops, but Waterstones is better than your average bookshop chain, and the Lancaster Waterstones in particular, which its gorgeous storefront that stretches along a city block. With big windows, great displays, little nooks and crannies and staircases leading to more places to explore. It’s a gorgeous store, with great kids’ displays too, and my children were immediately occupied by reading and also by a variety of small plush octopuses. I ended up getting Susan Hill’s Jacob’s Room is Full of Books, a follow-up to Howards End is on the Landing, which I bought when we were in England in 2009 and Harriet was a baby and I spent our week there reading it while she napped on my chest. Jacob’s Room… would turn out not to be as good as Howards End…, which broadened my literary world so much (and introduced me to Barbara Pym!). The new bookwas kind of rambling and disconnected and not enough about books, but was so inherently English that I was happy with it.

On the Wednesday we drove across the Pennines to Ilkley to visit The Grove Bookshop, which is one of my favourite bookshops ever. It’s located up the street from Betty’s Tea Room, which makes for one of the best neighbourhoods I’ve ever hung out in. After afternoon tea, where the children behaved impeccably, we took them to a toyshop for a small present as reward, which was good incentive for their behaviour in The Grove Bookshop too, where I was able to browse for as long as I liked. I love it there, the perfect bookshops and well worth a trip halfway across the world. I had been in the mood for a Muriel Spark novel since reading this wonderful article, and The Grove Bookshop delivered with The Ballad of Peckham Rye, a new edition in honour of Spark’s centenary. I was also very happy to find a rare copy of Adrian Mole: The Collected Poems, as Mole’s work has had a huge impact in my own development as an author and intellectual.

I really loved The Ballad of Peckham Rye, so weird and contemporary in its tone, strange and meta, the way all Spark’s work is. When we’re on vacation, I don’t like getting out of bed, lingering instead with a cup of tea and toast crumbs, and Peckham Rye was perfect for that,

On Friday we went to Storytellers Inc, located in Lytham-St. Anne’s, just south of Blackpool. Originally a children’s bookshop, they’ve branched out to books for readers of all ages, although the children’s focus remains—they have a huge selection of kids’ books and a special kids-only reading room with a tiny door and kid-sized furniture. (Sadly, we’d not brought our kids along with us that afternoon and it would have been weird to go in there without them.) In addition to the kids’ books, they had lots of Canadian fiction, and poetry. We ended up buying Welcome to Lagos, by Chibundu Onuzo, just because we liked the cover. And also Motherhood, by Helen Simpson, because I’d seen it on the shop Instagram page, and then I saw that Emily was reading it.

I don’t think I’ve ever read Simpson before, but this is a mini-collection of her stories from a few different books over the decades—and I loved it. Plus there was a boob on the cover. I finished reading it on the plane journey home, and then started Welcome to Lagos, which was really great. It’s Onuzo’s second novel, after the award-winning The Spider King’s Daughter. The latest is about a ragtag crew who arrives in Lagos and attempts to make a life there, in spite of the odds. They end up running in with a corrupt former Minister of Education with a suitcase full of money, and what they choose to do with this fate will make or break their destinies. In this case, choosing to buy a book for it’s cover was a very good decision.

March 8, 2018

The Red Clocks, by Leni Zumas

The week before we went away when I was sick in bed, I was reading Leni Zumas’s The Red Clocks, which I purchased after reading the review in The New York Times. I wasn’t reading it with an eye toward review, and I honestly wasn’t sure how I felt about it as I made my way through the novel—it’s a strange narrative, constructed of five different women’s voices that would have been “woven together” in another book, but this isn’t what’s happening here, and it wasn’t until close to the end of the novel that I really understood how the pieces were fitting. I really liked it, this novel about a dystopian America situated a week from now in which abortion is once again illegal.

The week before we went away when I was sick in bed, I was reading Leni Zumas’s The Red Clocks, which I purchased after reading the review in The New York Times. I wasn’t reading it with an eye toward review, and I honestly wasn’t sure how I felt about it as I made my way through the novel—it’s a strange narrative, constructed of five different women’s voices that would have been “woven together” in another book, but this isn’t what’s happening here, and it wasn’t until close to the end of the novel that I really understood how the pieces were fitting. I really liked it, this novel about a dystopian America situated a week from now in which abortion is once again illegal.

“She was just quietly teaching history when it happened. Woke up one morning to a president-elect she hadn’t voted for. This man thought women who miscarried should pay for funerals for the fetal tissue and thought a lab technician who accidentally dropped an embryo during in vitro transfer was guilty of manslaughter. She had heard there was glee on the lawns of her father’s Orlando retirement village. Marching in the streets of Portland. In Newville: brackish calm.”

It’s fitting, really, that I was unable to see how the voices in the novel were fitting together, because I don’t think they were supposed to fit together. Zumas does interesting things with the idea of women being in competition and opposition with/to each other, and how difficult it is to support other women who make different kinds of choices. Mostly because, I think, we’re often told that there is not enough to go around and that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. But the point of the The Red Clocks is that ultimately, our fates are all connected whether we like it or not, and that as a woman there is very little that can happen to women that in the end has nothing do with you. Zumas makes this all the more meaningful by connecting fertility and infertility to the abortion question, which I’ve realized it really should be, all being about questions of choice. In the book, a high school teacher has to figure out whether or not to help her student obtain an illegal abortion, all the while she is undergoing to fertility treatments (but not IVF, which has been outlawed) and being made ineligible to adopt at the government brings in rules stipulating that all adopted children have two parents (because what are all these laws about but keeping women from controlling their bodies and shaping their lives after all…).

There’s a whole lot more to it than that, fascinatingly, and it’s all very stranger and weirder than you might expect, but also not at the same time. I liked this book a lot.

February 22, 2018

The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore, by Kim Fu

I’ve read twelve books this month (so far!), barrelling through each one with gusto. They have been so good and I haven’t encountered a bookish dud in weeks and weeks—which meant that Naben Ruthnum’s recent tweet really resonated with me: ‘You haven’t “lost the ability to read,” you are just being lazy. Fuck the neuroscience, leave your phone in the other room and have some discipline.” YES. Or else you’re reading all the wrong books? Maybe I should be selecting your books for you, books that will recovery your ability to read—and top of the list is Kim Fu’s second novel, The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore. It’s a novel shaped like no other novel I’ve read before, original, heartbreaking, subtle and resonant. Packing a whole lot of story into a couple of hundred pages, I have no doubt that this will be one of the best books I read this year.

I’ve read twelve books this month (so far!), barrelling through each one with gusto. They have been so good and I haven’t encountered a bookish dud in weeks and weeks—which meant that Naben Ruthnum’s recent tweet really resonated with me: ‘You haven’t “lost the ability to read,” you are just being lazy. Fuck the neuroscience, leave your phone in the other room and have some discipline.” YES. Or else you’re reading all the wrong books? Maybe I should be selecting your books for you, books that will recovery your ability to read—and top of the list is Kim Fu’s second novel, The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore. It’s a novel shaped like no other novel I’ve read before, original, heartbreaking, subtle and resonant. Packing a whole lot of story into a couple of hundred pages, I have no doubt that this will be one of the best books I read this year.

Imagine a novel about summer camp, about a kayaking trip gone terribly wrong, a novel that holds within it the span of a life like The Stone Diaries did, except there are five lives. Nita, Andee, Dina, Isabel and Siobhan. Ten-years-old, the dynamics between them are complicated, alliances and enemies emerging in the relationships between any relationship proper. And then the first chapter ends, and the reader finds herself sweeping through the next three decades of Nita’s life, what happened (or, as the book is constructed, is still going to happen) at camp just one detail among many that informs the person who Nita becomes. Or is it so incidental? Which is the question about which Fu’s narrative hangs.

Every other chapter outlines chronology of the camping trip, interspersed with the story of who each girl becomes—puberty, high school, friendships, sex, independence, marriage, motherhood—years and decades going by at a clip but Fu pinpoints her details so well that these chapters are each like a novel in themselves. (Some of the girls’ lives are more elusive than others; we see wha happens to Andee, the “scholarship camper” through the prism of her sister’s experiences.) And then once we get to end of the novel and know what happened to the girls on their trip, those children, those hapless (maybe?) re-enactors of Lord of the Flies, each woman’s story is cast in a different kind of light. And just a note that what actually transpires on the trip is kind of banal in its disturbingness—or is it? Is it more disturbing that this story is banal? All of which is to say that those with an aversion to stories about children in peril need not avoid reading this book. Nick Cutter’s The Troop this is not, and they don’t encounter any witches in gingerbread houses. That they don’t need to is a testament to Fu’s craft though, as she is making a lot here out of very little. Or making a little out of a lot, and this is the question the novel hangs on in the most fascinating way.

February 5, 2018

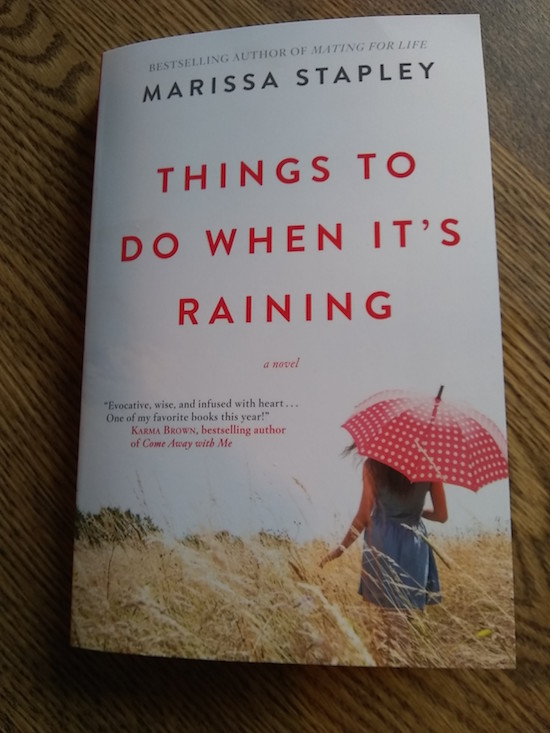

Things To Do When It’s Raining, by Marissa Stapley

I didn’t know Marissa Stapley when I read her debut novel Mating For Love four years ago, and loved its bookishness, intelligence, and what a pleasure it was to read it. In the years since I’ve come to admire her criticism, her championing of commercial fiction and its writers, and her feminist take on the CanLit community. And I’ve also come to benefit from her community directly, with her support of my own book when it came out last year, and with her friendship. Which means that I’ve been especially looking forward to her second book, Things to Do When It’s Raining, and I’m thrilled that it’s finally here. I read an advanced copy back in January, and I devoured it in a day.

It begins with Mae Summers, whose fiancé has just disappeared along with all of the money people had invested in their business, and who turns out not to be who he said he was. Her life in pieces, Mae decides to go home again, back to the inn in the 1000 Islands where she was raised by her grandparents after her mother’s tragic death. But all is not well at home either—a secret hidden in Mae’s grandparents’ past has returned to the surface and disturbed their relationship, plus Mae’s old flame and first love is back in town, right at the moment when she’s most raw and shaken.

Obviously, with a set-up this riddled with landmines, this is going to be a book with twists and turns, plus an impromptu journey to Niagara Falls. The plot had me fixed, but I was especially in love with Marissa’s prose, her words and sentences, not to mention the amount of wisdom contained within. About life, and about love—this is a story that’s so rich. The advanced copy I read in January didn’t come with the reader’s guide contained in the final book, in which Marissa explains that the story was inspired by one in her own family history, but when I read this it illuminated the story for me, its meaningfulness and resonance. Although part of it too was that it’s also written by a wonderful writer. And I particularly loved the book’s structure, the chapters moving between different characters’ points of view, but each one preceded by an item from the list that gives the novel its title. “Things to do when it’s raining,” written by Mae’s late mother in her youth, so that her voice infuses the novel like the presence of a ghost, so that we know full well what the other characters are missing. And the subtle ways these items tie into each chapter: “Build something. There are tools and scrap wood in the shed. And yes, bandages and ice in the kitchen, in case you accidentally hammer your finger.”

I received a finished copy of Things to Do When It’s Raining, but I’m fully intending to buy one too, which means I’ve an extra now for giveaway. Leave a comment on this post and let me know your favourite thing to do when it’s raining, and I will randomly choose a winner. Canadians only please, for postal reasons. And happy book birthday, Marissa!

UPDATE: Thanks for the comments, everyone! The winner has been chosen via Random Number Generator (i.e. very scientific…)