September 6, 2018

In Love with Lane Winslow

If you’ll recall, I did it wrong and read It Begins in Betrayal, by Iona Whishaw, last spring, having not yet read the previous three books in her Lane Winslow Mystery Series, but maybe it didn’t even matter, because I fell totally in love with the book, its characters, and Iona Whishaw’s fictional world, and the idea that I had three more books in the series to go back and discover was the very best news, and so I made this my summer project. So in June, I went back to the start and read A Killer in King’s Cove, about Lane Winslow’s arrival in the rural BC town after heartbreaking and dangerous experiences during World War Two, in which she’d served her country as a spy. But if quiet is what she’s seeking, Lane finds very little of it in her new life, where she is conspicuous as a young and very pretty woman who’s unattached and likes living alone. It doesn’t help either that dead bodies keep coming her way—and in the first book, it’s a body that’s washed up in her creek. When the local constabulary arrives, Lane herself becomes a suspect, her conspicuousness only underlined by the fact she cannot disclose much about her background and she seems to have an uncanny knowledge about things that are inappropriate for women to be concerning themselves with. And it’s here where Lane’s relationship with the dashing Inspector Darling is first sparked, but it takes until the end of Book 3 for both of them to realize and admit it.

I took Book 2, Death in a Darkening Mist, on vacation in July—body turns up in a hot springs, and there’s a whole Soviet spy plot—and it proved a most excellent companion. I read it very quickly, and continued to delight in the novel’s polish and smarts, and that the feminist threads I’d see in It Begins in Betrayal are woven all the way through. And finally, I read Book 3, An Old Cold Grave, this weekend, where the body turns up this time in a root cellar, and it’s a beautiful novel whose ties go back to British Home Children and their exploitation, but it’s also about women’s emancipation and independence from their fathers and husbands, and the terms under which Lane and Darling are going have a relationship—if one is finally going to happen.

So I’m all caught up, but it’s not over yet, oh no! Because this month A Sorrowful Sanctuary arrives, a mystery that explores Canada’s ties to Nazism, and I’ve read enough to know I’m probably good to have really high expectations. I’m looking forward to reading this one, and in the meantime, I’d encourage anyone—particularly those with a penchant for British cozy mysteries and detective fiction with excellent female characters—to pick up the preceding novels in the series. Iona Whishaw’s books have been the highlight of my reading year.

August 30, 2018

Women Talking, by Miriam Toews

“No Ernie, says Agata, there’s no plot, we’re only women talking.”

Women Talking, the latest novel by Miriam Toews, is not an easy read. Not easy because of the places it takes its readers to—the women talking in Women Talking are women from a Mennonite community in Bolivia, women whose husbands/brothers/sons have been accused to raping the women while they were sleeping, incidents based on real events, so-called “ghost rapes,” and it’s how women respond to and try to move on from this trauma that raised important questions for Toews as she considered writing this book, more than the fact of the violence itself. Because violence is ubiquitous. As Toews said in conversation with Rachel Giese when I went to see her last week, she can imagine what a rape is like. But what happens after—how do you imagine a way through that? And then she said something else, an echo of line in the novel which I read a few days later: “We are all victims, says Mariche./ True, Salome says, but our responses are varied and one is not more or less appropriate than the other.”

This line reminded me of Jia Tolentino’s article in The New Yorker on The Women’s March in 2017, and the way that so many were quick to jump on organizational conflicts and disagreements as a way to dismiss the movement altogether. Scoffing is often what happens when we hear about women talking—it’s either idle gossip, or else a petty scrap. A catfight. Women talking—it’s on the background, unless the voices are shrill. Or when they’re allowed to be a chorus. But in her novel, Toews dares to make women talking everything. The “there’s no plot” line is a funny meta-joke. But this is difficult too, on a practical level. To follow along with the conversations, to discern who these people speaking are as we’re just beginning to know them as characters. And Toews complicates the work further by refusing to make any of her characters just one thing—these are women who are difficult, who argue with each other out of spite, who contradict themselves and turn their own arguments inside-out, because this is what thinking is. For the first half of the novel, I confess that I was a little bit lost, finding the narrative hard to follow, and not remotely sure how the whole thing would come together.

But then mid-way through, something happened—it was like the walls started closing in on the threat to these women in the hayloft talking, these women who were daring to defy their husbands, brothers, sons. To explore the three options available to them: do nothing, stay and fight, or leave, but then the men who’ve gone to the city to post bail for the others could return at any time. And suddenly this novel without a plot takes on the most furious momentum and becomes unputdownable. In this novel in which nothing’s happened yet, something is going to have to give—but what?

The women talking in the novel are people who’ve never learned to read or write, who cannot read a map, and know nothing about the world beyond the boundaries of their communities. (I read this book right after Claudia Dey’s Heartbreaker, which is such a completely different novel in spirit, but there’s a kinship between them.) As the women in the novel are illiterate, writing down the minutes of their meeting is tasked to August Epp, an estranged member of the community who has returned after years away to serve as a school teacher (which is basically to be a failed farmer, and shameful occupation for a man). And August’s own complicated story, and his love for Ona, one of the women whose words he’s recording, becomes a foundation for the novel, as it would be, although just why or how does not become apparent until the conclusion, which only adds to its devastating and beautiful ambiguity.

August 15, 2018

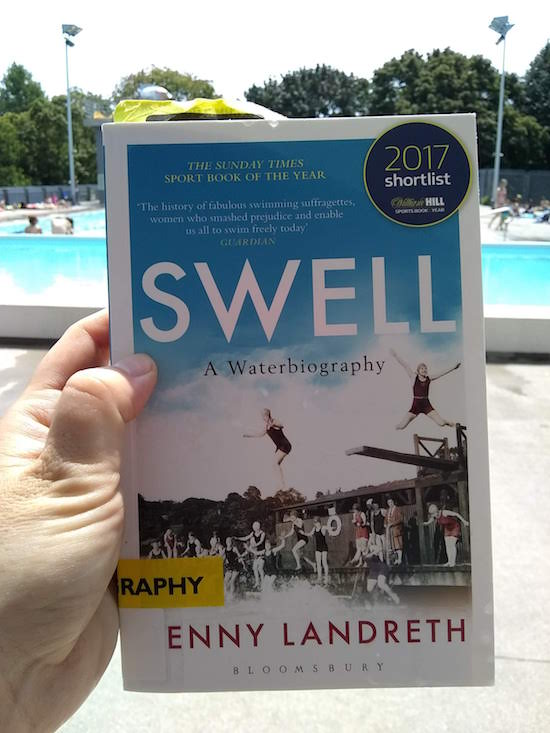

Swell: A Waterbiography, by Jenny Landreth

The gendered nature of swimming is something I think about all the time, although most often when I am sharing a lane with a man who has found taking up ample space by merely having longer limbs than I do unacceptable, and therefore has decided to enhance his lengths with flippers on his feet and paddles on his hands, increasing his chances of making violent contact with my body as he passes me. The women in the pool I swim at don’t do this, and neither do they, as one swimmer in Jenny Landreth’s spectacular book Swell: A Waterbiography does, butterfly up and down narrow lanes driving all other swimmers into the gutter. In her recent book, Boys, Rachel Giese writes about the way that boys are taught to be entitled to public space, as they dominate the basketball courts on the playground, and because I spend most of my time hiding in libraries, I don’t encounter this very much, but it’s in the pool I do. And it all makes me think of the line on the very first page of Swell, which was where I fell in love with this book: “how swimming can be a barometer for women’s equality.” We’ve all come a long way, but still.

Swell is my favourite book I’ve read this summer, a summer that has been all about swimming, in pools and lakes, as both my children are both at pivotal stages in the development of their inner fishes, and we can worry slightly less about the little one drowning. I’ve gone swimming by myself four mornings a week along with the men with the hand paddles and the flippers, and then later in the day we’ve all gone to the public pool and I’ve sat in the shallows and tried not to think about pee as my daughters delighted in turning somersaults over and over again. So yes, Swell was just absolutely perfect.

It’s a book I’d situate as what might happen if Sue Townsend of Adrian Mole fame got together with Elizabeth Renzetti’s Shewed and they decided to have a literary baby that was also a social history of women swimming in England. The result is absolutely delightful, empowering, and so terrible funny in its asides that I kept reading them aloud to the people around me who became very confused about what this book was about exactly. But that’s because it’s about everything, about the history of suffrage, and bathing suits, and public pools, and mixed beaches, and how women used to drown all the time because they weren’t taught to swim, and about how when they decided they did want to learn how to swim, no one could teach them because all the instructors were men and men and women couldn’t possible swim together. It’s about pools where women were accorded very little time for swimming, and it was usually during the day when no one could make it anyway. It’s about women who defied convention (and their mothers!) to become swimming superstars, pioneering the front crawl in England, swimming the English channel, being the first women swimmers in the Olympic games.

Landreth writes, “‘In front of every great woman is another great woman… Women whose lies will change. Some who will take this story, make it their story and push it on to its next pages.”

And of course, Landreth’s own story is part of this book, her “waterbiography”—and she admits to being proud to have coined the term. She grew up in the Midlands, which is kind of a swimming desert—when I lived there I was once so desperate for a swim that I dove in the duck pond on the Nottingham University Jubilee Campus—and was an unlikely candidate to become an avid swimmer for a host of reasons. She writes about learning to swim as a child, about travelling to Greece in her 20s and trying proper swimming for the first time, about lacklustre swimming as part of the 1980s’ fitness craze, about what an awful and unfulfilling thing it is to go swimming with small children—and then about finding her identity as a swimmer once her children were older, and what a thing it is that women can do this at any age. About how empowering it was to learn to call herself a swimmer.

There is indeed something womanly about swimming, in spite of the Michael Phelpses and the men with paddles on their hands. I mean, have you ever heard of a male mermaid? No. And I can’t for the life of me think of a single man who’s swam across Lake Ontario, but I know about Marilyn Bell and Vicki Keith, and Annaleise Carr, a swimming hero for every generation. I have dreams of one day swimming in the Ladies Pond at Hampstead Heath. I used to buy terrifically fancy swimsuits, but lately I’ve become enamoured of my sporty suits, the ones I wear while swimming in the pool in the mornings. Where my favourite swimmer is this woman I’ve never spoken to, but she’s my hero—grey bathing cap (I wouldn’t know her without it) and same bathing suit as mine, a bit stocky, older than I am. And in the pool every morning, she’s the fastest every time.

More on swimming:

- Swimming Holes We Have Known Blog

- Katrina Onstad on public swimming pools

- Nathalie Atkinson’s article in Zoomer Magazine on swimming books (which is where I heard about Swell).

- “Drowning at Midlife? Start Swimming” from the New York Times.

- “Swimming pools are a balm for whatever ails me”

- And a swimming quilt!

August 7, 2018

Sodom Road Exit, by Amber Dawn

I’ve had Amber Dawn’s Sodom Road Exit waiting for me since the beginning of May, when I bought it right after seeing her speak on a panel on genre at the Festival of Literary Diversity. She was fantastic on the panel (along with Cherie Dimaline, David A. Robertson, and Michelle Wan), explaining that Sodom Road is an actual road with an exit off the QEW to get to her hometown of Crystal Beach, on Lake Erie, which was once a thriving resort town with an amusement park famous for its terrifying roller coaster. Her novel is set during the summer of 1990, a year after the amusement park closed and things are officially in decline. Which is when Starla Mia Martin returns to town, driven by debt and desperation to move back in with her mother, and then inadvertently begins to channel a ghost who is powered by relics from the old amusement park, the spirit of a woman who’d been killed in an accident on the roller coaster decades before. But is this a benevolent spirt? Is she helping Starla get back on her feet, or is she only making it worse—and for a good portion of the book, it’s hard to tell. Starla gets a job working at a campground on the graveyard shift, which doesn’t help calm her mind at all, or reduce her propensity for being haunted. And as her connection to the spirit intensifies, Starla’s situation is complicated by the relationships she’s developing in Crystal Beach, in spite of herself—with her boss at the campground, an Indigenous woman who lives there and is struggling to maintain custody of her son, with the former high school classmate who dances at the local bar and with whom Starla might possibly think about entering into a relationship…were she the type of person who did such a thing as have loving relationships, and also if she wasn’t already cavorting with a woman who’s been dead for fifty years.

I’ve had Amber Dawn’s Sodom Road Exit waiting for me since the beginning of May, when I bought it right after seeing her speak on a panel on genre at the Festival of Literary Diversity. She was fantastic on the panel (along with Cherie Dimaline, David A. Robertson, and Michelle Wan), explaining that Sodom Road is an actual road with an exit off the QEW to get to her hometown of Crystal Beach, on Lake Erie, which was once a thriving resort town with an amusement park famous for its terrifying roller coaster. Her novel is set during the summer of 1990, a year after the amusement park closed and things are officially in decline. Which is when Starla Mia Martin returns to town, driven by debt and desperation to move back in with her mother, and then inadvertently begins to channel a ghost who is powered by relics from the old amusement park, the spirit of a woman who’d been killed in an accident on the roller coaster decades before. But is this a benevolent spirt? Is she helping Starla get back on her feet, or is she only making it worse—and for a good portion of the book, it’s hard to tell. Starla gets a job working at a campground on the graveyard shift, which doesn’t help calm her mind at all, or reduce her propensity for being haunted. And as her connection to the spirit intensifies, Starla’s situation is complicated by the relationships she’s developing in Crystal Beach, in spite of herself—with her boss at the campground, an Indigenous woman who lives there and is struggling to maintain custody of her son, with the former high school classmate who dances at the local bar and with whom Starla might possibly think about entering into a relationship…were she the type of person who did such a thing as have loving relationships, and also if she wasn’t already cavorting with a woman who’s been dead for fifty years.

Things get complicated Or even more complicated? Starla, following the instructions of the spirit, has a memorial gazebo erected out of materials from the amusement park, and people begin to travel from miles around to witness her communing with the dead and perhaps channelling their own lost loved ones. But the toll of these experiences and the burden of Starla’s connection to the spirit become too much for her to carry and her mental and physical health begin to suffer, so much so that soon the people who love her are frightened for her life.

I picked up this book because I was intrigued by the setting, and also so fascinated by Dawn’s remarks on genre and the idea of the novel as a container for a ghost story. And I was a little bit intimidated to finally start reading it because a) it had the word “sodom” in the title, b) it was a solid brick of a book and was I ready to commit to that many pages, and c) in order for the premise to work, it would have to be a really, really exceptional novel. Which, it turns out, it is. I loved this novel. We were camping the weekend before last, which isn’t always the best place to be reading, because there are bugs, and chores, and children setting themselves on fire, but all these things took a back seat as I read 300 pages of this book in two days, and came home and read the rest once the laundry was done, because it really was that compelling, so masterfully crafted. It’s a perfect gripping amazing summer read, but it’s also underlined with substance—the stakes are real here. I absolutely loved it.

August 1, 2018

Summer Books on the Radio

I was on CBC Ontario Morning today talking about amazing summer books—including two I’d already mentioned, but I hadn’t talked about them then, and I absolutely had to come back and enthuse because they’ve been highlights of my summer, along with all the rest. You can listen again to my picks on the podcast: I come in at 30.00.

July 31, 2018

The Journey to the Journey Prize

I’m so pleased to share the news that I’m a juror for the The Journey Prize this year, along with Sharon Bala and Zoey Leigh Peterson. And I’m pleased not just because it’s such an honour to be part of this project, a prize that has played a part in the careers of so many superstar Canadian writers. A prize that I always had secret dreams of being a finalist for—the closest I ever came was having a story of mine nominated way back when, and even that was something I was a little bit proud of. I’ve written before about how exciting it was to buy a copy of the anthology in 2008 when my friend Rebecca Rosenblum was a finalist—my friend was in an actual book! And so to be a juror—what a huge and incredible thing. But the honour is just the beginning—I want also write about how it’s been an absolute delight and that I’ve learned so much from the experience as a reader. It’s been so interesting.

This opportunity arrived in my inbox early this year, and I did not hesitate to say yes, because if there is any evidence that I’ve succeeded in making a name for myself as a reader, this would be it. It felt great to be in the esteemed company of Sharon and Zoey as well—I’d just read Sharon’s novel, The Boat People, and loved it, and I’d been hearing people raving about Zoey’s Next Year, For Sure since it was published. And then it would not be long before a giant envelope was delivered to my house, and I began the process of reading 100 short stories that had been published in journals and magazines across the country, which meant there was so much goodness, and it would be my job to help figure out the best of the best. I began a big knitting project as I started reading the stack, and I knit as I began reading, and also lugged the stack of stories over to the pool and read it on the bleachers while my children did their swimming lessons. When I think of that stack of stories, I think of sunny Sundays with pages spread out on my bed and also chlorine.

And then I sent in my shortlist of 15 or so stories, and I thought that it was pretty cut and dried. Several stories it seemed obvious to me were excellent, and others were pretty easy to reject, because some things are simple, right? And then I received our collective longlist, which was 30-some stories, and some of the picks were baffling—really? Maybe this was going to be harder than I thought…but I started reading again, and something amazing happened. Reading these stories in a new context was so illuminating, and understanding that my colleagues supported some of these stories made me read them differently. I also reread some of my own favourites, and wondered if my enthusiasms had perhaps been ill-placed. A few stories continued to stick out as extraordinary, and the rest of them were the same stories they’d always been, but my mind had changed. What a thing! To adjust and correct as a reader, to learn from my colleagues, to benefit from their broadening of my perspective.

And this only kept happening as we got to know each other through conference calls, as we debated and enthused, asked questions and posed answers. There was such generosity in the spirit of the work we were doing, a willingness to listen to each other and learn. I’d previously had an experience on a jury with someone who simply dug in his heels and refused to listen to anyone, and he’d ruined the entire experience for me—and I’m still so angry that we let him get his way, but in the end I just wanted to get home for lunch. With Zoey and Sharon though, every bit of our conversation was about listening and building, and at those moments when one of us dug in our heels, it was absolutely the right thing to do.

The list we settled on could not have been more perfect, and all of us were so satisfied with it, and excited as we took on the task of arranging story order and writing our introduction. That giant stack of stories had been whittled down to something that was an actual book, rich with cohesion and connections, both obvious ones and others that were surprising. And I’m so excited now, for the shortlist to be revealed on August 7, for the book to find its way into readers’ hands, for these stories to be read—I don’t know that I’ve ever felt so personally connected to a book I didn’t write. But I can tell you with assuredness that it’s such a good book, and I’m excited for the next stage of its journey into the world.

Update: In all my rhapsodizing for my co-jurors, I forgot to give credit to McClelland & Stewart and the incredible Anita Chong, who is the whole reason this experience has been such a pleasure. Anita is so incredibly good at what she does, and I’ve been so grateful to get to know her and work with her on this book.

July 25, 2018

New Summer Reads

I feel selfish keeping my vacation reads to myself, not sharing them properly in reviews (even if those reviews are kind of mini). These books are great, and I want to tell you so properly…

A Tiding of Magpies, by Steve Burrows

A Tiding of Magpies, by Steve Burrows

The fifth instalment in the Birder Murder Detective Series, which I’ve been a fan of since 2014, I really loved this one. It’s a decidedly post-Brexit novel in which non-domestic birds are causing havoc on the landscape and response is mirroring the xenophobic human population. Detective Chief Inspector Dominic Jejeune is in an interesting place here as an immigrant from Canada, and an expert bird-watcher no less, and when a body turns up (of course) he finds himself distracted by an inquiry regarding his most famous case, and all the while he suspects his girlfriend is in serious danger. As we’ve come to expect from the series, this novel is smart and thoughtful, and rich with suspense.

*

Sunburn, by Laura Lippman

Sunburn, by Laura Lippman

Last year Lippman’s Wilde Lake was a summer reading highlight for Stuart and I both, so we did not hesitate to pick up her latest, which was enthralling and full of twists and so excellent. Laura Lippman is a masterful crafter of both plots and sentences, and this story is truly original and so steeped in atmosphere. Read this to find how how Sunburn is a subversion of the “dead girl” trope.

*

How To Be Famous, by Caitlin Moran

How To Be Famous, by Caitlin Moran

And finally, I am such a Caitlin Moran completist that I even own The Chronicles of Narmo, which she published at age 16. This one is her “second” novel (or third, counting Narmo, which I don’t think she does), a follow-up to How to Build a Girl, and it’s a love letter to Brit-pop and the 1990s, and also a fantasy novel in which teenage girls are loved, valued, and confident in everything they deserve. A self-fulfilling prophecy, I hope? I’l definitely be passing it onto my daughters when it’s time.

July 16, 2018

Summer Reading

When we arrived at our rental cottage up north last Saturday, I was surprised to feel troubled, because here we were in the most idyllic place imaginable on a glorious summer day, the beginning of a splendid week. But it was unease that I encountered—so slight but visceral—as I climbed the hill, took in the vista, and walked the paths I last walked almost a year ago. A few moments before it all clicked: it had been the books, of course. And also the weather—last summer the sky was always dark and brooding and there were storms every day. It was such an uneasy summer, climate-wise, and the books I’d brought along with me only complemented the atmosphere. It is possible that anyone would feel disturbed upon returning to the place where they’d read Emily Fridlund’s History of Wolves, I mean, or experienced the intensity of Liane Moriarty’s Truly, Madly, Guilty. Wilde Lake too, which was a modern take on To Kill a Mockingbird, but with more sinister undertones. Our last night there I started reading a Louise Penny novel and the weather in the opening chapter was identical to the thunder storm crashing outside our cabin window, and I began to wonder if the line between fiction and reality had become blurred. It really was intense, all of it, nine books in a week the definition of intensity anyway. So that when I arrived back there, it all came back, those incredible books I’d been so wrapped up in.

Last year’s summer reads.

It’s funny how books stay with you, and not always in the ways you’d expect. I really enjoyed Jessica J. Lee’s Turning: A Year in the Water last year at the cottage, but it wasn’t a book I expected to return to. I gave that book away in the spring, but when I jumped into the lake last week (over and over again) I realized what a mistake I’d made, that here was a book that had changed my life. I’ve been jumping into lakes and pools ever since I read it instead of easing my way in gently (and sloooowly) as in previous summers, thinking, “If Jessica J. Lee can use a hammer to crack the ice and jump in a lake in December, I’m certainly capable of a cannonball in July.” Back in the lake beside which I first read it, I realized how much this memoir needs a space in my book collection. How much all those books I read last summer had gotten under my skin.

I wasn’t sure how the reading was going to pan out this year—we were going on vacation with three other families, and while this was a very good plan, I was concerned that being surrounded on all sides by people I like might get in the way of my reading prowess. But it turned out not to be the case because, a) it turned out no one was interested in surrounding me on all sides 24 hours a day b) everyone else was reading too and c) our friends had brought their children, who whisked mine away for so much freedom, fun and adventure that I scarcely saw them all week long and therefore got to read so much that I almost go bored of reading. (Almost. I did, however, get bored of potato chips, shockingly, but that was only very temporary and things are back to normal.)

Anyway, it turns out that I read nine books again, and it was exhilarating and amazing. Liane Moriarty again, who does not get nearly enough credit for being a literary genius—the nuance and craft in her work is astounding. More Laura Lippman too, because she is just such an astounding novelist. The latest Birder Murder Mystery, A Tiding of Magpies, which was the first anti-Brexit novel I’ve read since Ali Smith’s Autumn (and it made me thinking about whether a good pro-Brexit novel was a literary impossibility). I really liked it, and also Death in a Darkening Mist, by Iona Whishaw, the third book I’ve read in the Lane Winslow mystery series which has really been a highlight of my summer. The new Caitlin Moran, which was so terrific, laugh-out-loud funny, powerful and profound. So glad to read Celeste Ng’s first novel after loving her latest a few months back. I was happy standing in line at Webers, because I had Tish Cohen’s Little Green in my bag, which was a certainly a novel that had me in its thrall. And Rumaan Alam’s That Kind of Mother still has me thinking about all the spaces in between its story and I think I’m haunted by the ending—such a subtly provocative book.

I wonder which of these will still be haunting me a year from now?

July 2, 2018

Florida, by Lauren Groff

It continues to be one of my favourite serendipitous things, reading a short story to realize I’d read it before, long ago, in an entirely different context. I wrote about this when I finally read Isabel Huggan’s The Elizabeth Stories in 2012 and realized I’d read “Celia Behind Me” two decades before in my Grade 12 English textbook: “And I realized that I’d read this story before, more than once. It was so strangely familiar, like something I’d known in a dream, but somebody else’s dream.” I remember it also happening when I read Lauren Groff’s “L. DeBard and Aliette” in her first story collection Delicate Edible Birds in 2009, and I realized I’d read the story in The Atlantic in 2006, that it was the first thing by Lauren Groff I’d ever read—before The Monsters of Templeton, even. Before I even realized there was such a thing as Lauren Groff, who has since gone on to become my very favourite writer.

I love “rediscovering” these stories for so many reasons, for the way it suggests the architecture of my mind is infinite dusty corridors and who knows what lies around the next corner, and also for how it underlines that nothing ever goes away. That those dusty corridors are lines with rooms that are full of stuff, everything I’ve seen or heard or thought or read, and how it’s still there, all of it, even if not immediately accessible.

Midway through Florida—which is a book I’d picked up with more expectations than previous works by Groff, but also with the expectation that I was to suspend all expectations because she never does the same thing twice—I came upon her story “Above and Below.” And partway through that story I realized I’d read this one before as well, in The New Yorker in 2011. And I remember not liking it. This was before Arcadia, before I properly understood the breadth of Lauren Groff’s literary ambition, of her range. This was before the world fell apart as well, after the global economy melted down in 2008 but in that quiet period where it seemed like it all might be okay, and those of us who didn’t live in places like Florida might have been fooled into thinking that progress was an ongoing story. I remember that I just didn’t see the point.

In the context of 2018 though, of this book itself, the story reads very differently to me. I also found it interesting to think about the story in the context of Arcadia, which was about a community that comes together and then falls apart, as the society depicted in “Above and Below” also seems to be unravelling, or at least it is for the protagonist—I see how it fits into her oeuvre in a way I wasn’t able to appreciate at the time. And it certainly does fit into this collection, which is of stories in which dread is creeping, danger lurks, children are stranded alone on islands, and the possibility that a sinkhole might open at any time beneath you is not especially remote.

Florida is a locality of extremes—I am frequently grateful for living smack-dab in the middle of the continent, as immune as one could possibly be from hurricanes, earthquakes, or alligators. When I hear stories like that of a sinkhole that swallowed an entire house, I think to myself, “Well, that’s a Florida story,” and go on with my day. Although if I’ve learned anything in the last few years, it’s that what’s going on at the edges, in the margins, has deeper ramifications than I ever really realized. That a story like “Above and Below,” about a character who loses everything and just keeps going—it seems less marginal now than it did in 2011.

I like Florida for how it’s a book as well as a collection of stories. I like stories, but when I pick up a book, a book is what I want, for there to be themes and connections that tie it all together. Not that the stories be linked, necessarily, but that they inform each other. Context matters. I want a story collection to be a book that’s capable of being grasped and understood as a whole. Which is the whole reason I’d be shaking this one emphatically and imploring you to read it: Florida! It’s so good. It will break your heart about this miserable perilous world, but you’ll also love that world a little bit more because this incredible book is in it.

June 26, 2018

Homes: A Refugee Story, by Abu Bakr Al Rabeeah

When I think back to Fall 2015, I can’t help but cringe. It was an awful time, absolutely shameful, when a deranged man with a gun attacked the Canadian parliament during the most awful Canadian election I can remember, when Ministers were announcing “barbaric practices hotline” and simply throwing up their hands when the body of a child washed up on a Turkish beach, one of so many migrants who’ve been drowned. People kept hearkening back to the response of Canadians to the Vietnamese refugee crisis, and wondering if some fundamental morality was missing from us now, or perhaps we’d all been overtaken by inertia. It was the worst of times—it just was. And then something shifted.

When I think back to Fall 2015, I can’t help but cringe. It was an awful time, absolutely shameful, when a deranged man with a gun attacked the Canadian parliament during the most awful Canadian election I can remember, when Ministers were announcing “barbaric practices hotline” and simply throwing up their hands when the body of a child washed up on a Turkish beach, one of so many migrants who’ve been drowned. People kept hearkening back to the response of Canadians to the Vietnamese refugee crisis, and wondering if some fundamental morality was missing from us now, or perhaps we’d all been overtaken by inertia. It was the worst of times—it just was. And then something shifted.

With the election of a Liberal Government that October, Canada’s hard policies toward refugees was eased, and families started arriving. Suddenly everyone I knew was sponsoring a Syrian family, or tutoring them in English, and families joined our school community, became my children’s classmates. It’s been an incredible story, albeit not a straightforward one, but what human stories ever are? Did you read the one about the chocolate company founded by a Syrian refugee and their Pride-themed chocolate bars? Remember when Chris Alexander blamed the Syrian refugee crisis on the CBC? Oh my goodness, I do not miss that guy one single bit.

I will note that Abu Bakr Al Rabeeah and his family arrived in Canada in late 2014, one of the lucky few that were permitted when Canada was being pretty stingy with welcomes. And that his is just a single story standing for many, but still, it’s a remarkable thing to hear a refugee story from a Syrian point of view. Homes: A Refugee Story, as told to Winnie Yeung, who was Bakr’s teacher at his Edmonton high school. He wanted to share his story, he told her, to honour his experiences, so much loss, the friends and family he’d said goodbye to when he left his home. And so together they created this book, which is categorized as a work of creative-nonfiction, Yeung writing in Bakr’s voice, with information gleaned from interviews with his family.

Together, they tell the story of Bakr’s early childhood, born in Iraq: “It wasn’t always like this. My life wasn’t always like a scene from Call of Duty or Counter Strike.” He remembers delicious food, being surrounded by family. But eventually it becomes very difficult to be a Sunni Muslim in Baserah, where they lived, and after a cousin’s body is found in a dumpster, the family decides to leave. In 2010, they received visas to relocate to Homs in Syria where they already had family, and a twenty-four hour bus ride leads them to their new home.

Soon after arriving, the family apples for refugee status—Bakr’s father suspects that Syria will not be any safer than Iraq, and his suspicions prove prescient with the arrival of the Arab Spring in 2011, which would come to throw Syria into its bloody civil war. The first sign is an attack on the mosque where Bakr and his family are praying, and this first time the response is disbelief—could they be being shot at? But eventually they’d become numb to the violence, accustomed to the sound of gunfire and explosions—though never to the terror of being approached by government thugs in the street. But even still, life goes on. Bakr’s father tells him: “Death doesn’t matter. Money doesn’t matter. Even life doesn’t matter, son. What matters is living your life with your family, with the people you love. We love each other, hard, and hold on tight. What we face, we face together. Together we can move forward and every little happiness we can have, we enjoy. We cannot let hatred and fear stop us from living.”

This is a story about an ordinary childhood against an extraordinary backdrop—eventually the schools close, the field where Bakr and his friends play soccer is overtaken by snipers, Bakr witnesses his first massacre, and then another one—what kind of a childhood is that? But then the family wins the lottery (literally) and receives permission to travel and make a new home in Canada. It’s such a long way from there to here, but Bakr (and Yeung) are so generous in sharing the journey.

- This book nicely complements Ausma Zehanat Khan’s A Dangerous Crossing, a gripping novel about the plight and trauma of Syrian refugees that similarly brings the story of this brutal war to life.