May 1, 2020

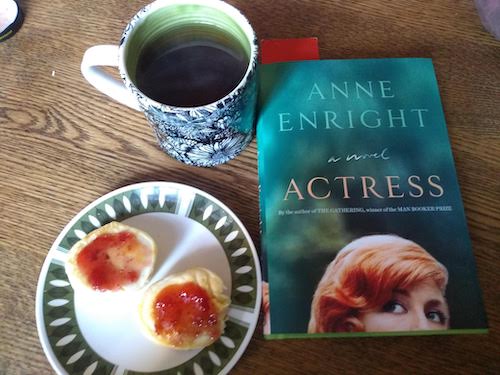

Actress, by Anne Enright

I find Anne Enright difficult, but not in the way I find other writers difficult. Which is so much so that I have absolutely no desire to read them, because life is difficult enough. But the work is usually worth it with Anne Enright, whose books are strange and beguiling, although ordinary at first glance—although I didn’t love her most recent The Green Road so much, a novel that was interesting that never really hung together in the way I wanted it to. For me, Actress was more satisfying, but also strange and disorienting, which isn’t a bad thing for a novel. Uncanny: to be both at home and not at home.

It’s the kind of book that’s just so specific, the kind of book of which you can’t say “it’s the kind of book…” at all otherwise. It’s so specific that’s difficult to fully comprehend that this is fiction, that Enright made the whole thing up, the singularly personality and career of Katherine O’Dell, the Irish theatre legend, her story told by her daughter, Norah, who grew up in her mother’s shadow, but this experience too is singular, as human experiences are. This is no Mommie Dearest, is what I mean. It’s so richly imagined and then filtered through the lens of Norah’s perspective, who’s missing half the details. A story by a daughter of her mother that is not a story of neglect or a litany of grievances, though there are some of these, but no more than with any human being. A different kind of take on mothers and daughters, that one can regard the other as a human being—albeit a complicated and flawed one, one who was eventually admitted to a psychiatric hospital after shooting a producer in the foot (which was less funny than it sounds—the injury caused torture for the rest of his days).

I appreciated this novel more after having read Say Nothing, by Patrick Radden Keefe, which filled in my understanding of The Troubles in Northern Ireland in the 1970s, though this part of the story is peripheral in The Actress. Intentionally so, because there are many things that Norah doesn’t want to know about her mother. But the part that resonated for me as I read this book in April 2020:

A funny thing happens when the world turns, as it turned for us on the night we burned the British embassy down. You wake up the next morning and carry on.

Anne Enright, The Acress

April 23, 2020

Misconduct of the Heart, by Cordelia Strube

I was nervous about this book, and if you’ve ever read Cordelia Strube you’ll understand. Cordelia Strube whose previous novel was On the Margins of These Pages, There is Heartbreak, or at least it might as well have been. (The book was actually On the Shores of Darkness, There is Light, it was one of my favourite books of 2016, and won the Toronto Book Award.) But my capacity for heartbreak is so currently occupied at the moment by everything, and I can’t take any more. So I went into this warily, is what I’m saying, like the book itself was an unreliable teenage boyfriend. “Here’s my heart, Cordelia Strube,” is what I was thinking. “Be careful, please.”

Misconduct of the Heart is not a feel-good comedy. Narrator Stevie is currently sandwiched between violent assaults by her son who returned from Afghanistan with PTSD and the demands of her aging parents (her mother assaults their personal support worker and her father shits his pants), all the while Stevie herself has trauma that she’s never properly processed or admitted to anyone. She became pregnant with her son after a violent gang rape when she was a teenager, and was never able to show him affection—though her own mother and father weren’t stand-out examples of parenting either, so did anyone ever have a chance?

But they do, which is the point of this book, which is as funny as it’s dark. Populated by the characters who work at Chappy’s, the weathered franchise restaurant in suburban Toronto where Stevie works as kitchen manager, and if you’ve ever worked in a kitchen, you’ll recognize the scene. High stress, as if Stevie needs any more—but then someone drops off a child who might be the daughter of her son, and here Stevie sees the possibility of something. Redemption? Could this troubled world ever give her that much?

This is not a feel-good comedy at all, but oh it’s so richly funny. Funny in the way the world is, absurd, preposterous, sad and hilarious. “You can’t make this stuff up,” kind of funny, which is funny because Strube does, and it’s wonderful. And even feel-good, because there is hope and there is triumph, and the reader is rooting for every single one of these lovable losers to finally win.

It’s a slow build, this book, and first 100 pages are tough—the narrative is a bit disorienting, we’re not sure why we care about any of these people yet, and the story of Stevie’s past and what happened to her son is really brutal. But the reader should persist because once the story picks up, the payoff is huge, such an unrelenting kernel of light and love. There is nobody else who writes like Cordelia Strube, and this is one of my favourite books of the year.

April 16, 2020

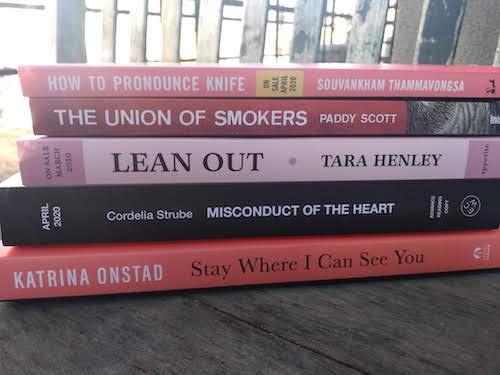

The Union of Smokers, by Paddy Scott

I confess that I cheated a bit with this one. A book about a twelve-year-old boy, “the heroic last day in the life” according to the copy on the back, and these days I just don’t have the stomach for heartbreak, so I read the last page first to see if this was a tragedy that was survivable—for me or the character, or both, perhaps—and I determined that it was. I could take this.

So I knew what I was getting into with Paddy Scott’s The Union of Smokers, is what I mean, but did I really? In this story of Kaspar Pine, a farm kid from the outskirts of Quinton, ON, which bears an uncanny resemblance to the town of Trenton, right down to the swing bridge and the creosote plant with a propensity for catching on fire.

Not everyone takes Kaspar seriously, in fact nobody really does, except Kaspar himself. (“Getting snorted at by women is bound to happen if you’ve learned your entire repertoire of charming manoeuvres from senior citizens.”) His mother’s whereabouts are unknown, and he was brought up by his father in a kind of deprivation, until circumstances changed and he was brought to live with his maternal grandparents on a farm outside of town. They, at least, provided him with the stability and love that had been missing from his life, and a sense of identity in farming culture, which most of the people who live in town don’t properly understand.

Kaspar, a prolific smoker thanks to the collection in his butt baggie, bikes into town to replace a canary (twice) and here is where the book begins, when he meets up with Mary Lynn, love of his life, just a couple of years older, with whom years before he’d once shared a dramatic adventure while dressed in a cowboy costume, but she doesn’t remember. The two of them become yoked, and it turns out their bond is even deeper than that, although not in the way that Kaspar longs for, and Mary Lynn herself has no idea what to make of this wacky weirdo kid who won’t leave her alone and ends up using her bra as a tourniquet, but not in a sexual way.

An eccentric portrait of small town life; a narrative voice that gets in your head and proves unforgettable, a story that manages to be utterly devastating and uplifting at once thanks to a character so strangely and richly imagined, with the most indefatigable sense of himself and his story and his worth—no matter what anybody else thinks, and you’re going to take his side. Not to mention be sorry when it’s finally time to leave it. I really loved this book.

PS I picked up the book finally after its virtual launch at 49thShelf. Throughout this month and next, we’re spotlighting new releases that deserve our attention at a moment when launches and festivals have been cancelled. Hope you can pay attention to what we’re doing here and do your best to support these books and authors.

April 15, 2020

Books on the Radio

Books are giving me life right now, at a moment when life itself is kind of thin, and so it was a pleasure to speak on CBC Ontario Morning today about five books that have been good for my spirits lately, as inspiration, distraction, and reasons for hope. You can listen again to my recommendations here—I come in at 44:30.

April 9, 2020

A Conversation With Tara Henley

Like many of you, I found myself unable to read as this crisis arrived in our lives, perpetually in a panic, scrolling news feeds instead. Not being able to read, however, only compounded the trouble I was in, because if I’m not a reader, then who am I? And it was Tara Henley’s new memoir LEAN OUT: A MEDITATION ON THE MADNESS OF MODERN LIFE that brought me back to books again, a gorgeously written memoir that is perfectly timed for our current moment. Henley was kind enough to answer some of my questions about the book, so please read on to learn about how Madeleine L’Engle’s books expanded her vision for her life, what are the limits of self-care, and how “right now we’re seeing in stark terms the price we all pay for inequality.” I love this book so much.

April 8, 2020

How to Pronounce Knife, by Souvankham Thammavongsa

Make your book pink. Make your book slim. Put a nail file on the cover, and have your reader forget that it’s actually a blade, and this is how you do it, create a story collection that seems unassuming but will cut you with its razor edge. The “Yes, Sir” delivered in a tone that really means, “Fuck you!” And it gets under your skin, of course, a book like this, Souvankham Thammavongsa’s fifth book after four acclaimed poetry collections and her debut fiction, the short story collection How to Pronounce Knife. (Full disclosure: the writer and I were classmates twenty years ago, and I since followed her career with admiration.)

These stories are subtle, wonderful and jarring. They range between those from the perspective of children of immigrant families from Laos (reflective of Thammavongsa’s own background), children who are know before many of their classmates the way that parents are actually fallible after all, that they struggle and have limits, and stories of people awkwardly navigating social and romantic mores, failing to fit in with convention (which is another way of not failing at all—especially in a story).

In the title story, a child takes her father’s guidance on the correct way to pronounce “knife,” and learns the lessons of a lifetime in the process. In “Paris,” a woman who works in a chicken factory dreams of getting a nose job—and experiences vicarious heartbreak. A seventy-year-old woman has an affair with her young neighbour in “Slingshot,” a story with the most perfect, powerful ending.

I LOVED “Randy Travis,” the story of a family who immigrates from Laos, and the mother falls in love with country music, which helps define for her a different kind of life she desires for herself. In “Mani-Pedi,” a failed boxer who ends up with no choice but to take a job at his sister’s nail salon—but who insists on keeping his dreams. “Chick-a-Chee” is about one family’s embrace of a bizarre local ritual. “The Universe Would Be So Cruel,” awesome and heartbreaking, about a man who runs a small print shop and has an uncanny knack for knowing the future for the couples whose invitations he creates. A child considers the mystery of her mother in “The Edge of the World.” A school bus driver realizes he’s losing his wife in “The School Bus Driver.” A mother watches her daughter from afar in “You Are So Embarrassing.” The story “Ewwrrrkk” begins, “The summer I turned eight, my great-grandmother showed me her boobs.” An accountant looks for love (and potential clients) in “The Gas Station.” A childhood friendship is recalled in “A Far Distant Thing.” And a young girl goes to work with her mother in the final story, “Picking Worms.”

The stories are quiet but powerful, the sentences extraordinary, the volume as a whole is such a pleasure to read and to discover.

April 2, 2020

No More Nice Girls, by Lauren McKeon, and Lean Out, by Tara Henley

Although almost everything I was reading a month ago seems kind of irrelevant now, Lauren McKeon’s No More Nice Girls feels like it could be an exception. This underlined by the number of Canadian politicians and public health officials who are women and spearheading efforts to fight and control what’s going on right now, women we are turning to for answers and reassurance, one of whom, Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland, shows up early in McKeon’s book as as “a new kind of power that’s completely, deliberately at odds with a very old, very masculine one.”

In her book, McKeon imagines what might be possible with a different kind of power, and writes about ways that people are imagining such things already, with all-women co-working spaces, the #MeToo movement, “identity politics of lonely, angry men” as a backlash to women’s power. She writes about how conventional power doesn’t tend to work for women when they achieve it, corporate achievement as an example, where the women at the top still have to contend with the same challenges that all women do—sexism, harassment, discrimination, violence, a gender pay gap. The ways in which women have to be “better than perfect” to be accepted, while any guy in a poor fitting suit seems to fit the bill. And the limits of #GirlBoss kind of power, which is the kind of individualized, status-quo sustaining power that the patriarchy likes.

It’s difficult to synopsize McKeon’s book, whose range is so wide. She writes about race and representation; economics and federal budgets; gender and the media; how technology affects our lives and what it means that so much of technology is created by men; feminist cities; online trolling (McKeon is author of F-Bomb: Dispatches from the War on Feminism, which I read and loved in 2017); and about numerous and inspiring ways that women all over the world are raising the bar and changing the narrative on traditional notions of what a life of a woman ought to look like. It’s an incisive and inspiring read.

*

I read No More Nice Girls in “the before times” and then was unable to read anything properly for a couple of weeks, as the world before my eyes was changed into a surreal and disturbing reality. And the book that finally brought me back to reading was Tara Henley’s Lean Out: A Meditation on the Madness of Modern Life. (Full disclosure: Henley wrote a kind and generous review of my novel back in 2017. We also share an editor. Neither of these factors are why I’m so obsessed with her book, but are definitely worth noting.)

Reader, this book was a balm, as it was always meant to be—but it meant so much more than it would have even a month ago. Suffering from physical symptoms of anxiety in 2016 after a decade of living in the big city and working in journalism, Henley reached a breaking point and realized that things would have to change—but also that she was limited as to what change was possible to her as an individual, this becoming even more apparent after she moves back to her hometown Vancouver and is confronted with the city’s unaffordability. Does modern life truly have to be like this, Henley wonders? A less solipsistic Eat, Pray, Love is how I am thinking about this book.

Lean Out is rich with reporting, but underlined by Henley’s own story and family history. (It’s also gorgeously written and inspired by the works of Madeleine L’Engle, which meant a lot to me after My Year of Vicky Austin.) She writes about alternatives to the way we do work, connect with nature, eat food, make and spend money, live online, combat loneliness, find community, and make our homes. Arriving at not definitive answers, but instead broadening the range of what is possible for a more fruitful way of living both as individuals and as a society. And, as with McKeon’s book, it all comes down to inequality in the end—data shows that unequal societies, Henley writes, make life demonstrably worse for everybody, even those who are at the “top.”

Which is something all of us should keep in mind as we think about what kind of world we want to live in “when all this is over.” I am so grateful to these authors who are already doing the work of imagining new and better ways of being.

*Both these books are included on a Books With Vision list I created at 49thShelf. And an amazing Q&A with Henley will be up on 49thShelf in about a week. Stay tuned. And buy her book in the meantime—you will be glad you did.

March 5, 2020

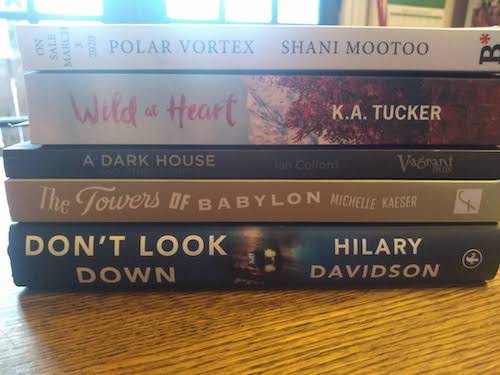

Polar Vortex, by Shani Mootoo

At first glance, this is a novel about a love triangle. Priya, who is married to Alex (a woman), and they live together in quaint and rural Prince Edward County. But something isn’t right, even before we learn that their household is about to be disturbed by a visit from Priya’s old friend, Prakash. Even notwithstanding Priya’s erotic dream about Prakash, which opens the novel. There is a distance that stands between Priya and her wife, and also a strange, uncanny hollowness to Priya’s first-person narration—or maybe it’s not hollow, but instead there’s a kernel of something there (what?!) that the reader is not privy to.

Prakash is a very old friend, a friend that Priya has barely spoken of to Alex, though she has pointed him out in an old photo from university, a photo of the two of them alongside Priya’s first girlfriend, Fiona. And is Alex threatened because he shares a cultural heritage with Priya? They are both diasporic Indians, Prakash from Uganda (where his family was expelled and brought to Canada as refugees) and Priya from Trinidad—though Priya would argue that this isn’t such a remarkable connection. But of course there is more to it, more than even Alex knows, more than Priya is willing to admit to herself or to even remember.

The novel takes place over the course of a day, and the tension in the text can be excruciating—but in the very best way. The kind of excruciating tension that makes a book unputdownable, that causes a reader to yell at a page. Polar Vortex becomes a book about truth and memory, about how little we know each other, and ourselves. Strange, ominous, haunting, it’s a propulsive read and a deliciously unsettling one.

March 4, 2020

March Books on the Radio

So happy to talk GREAT BOOKS on the radio this morning with the lovely Wei Chen, who even reads the books I recommend. If you missed it live, you can listen again on the podcast. I come in at 35.00.

February 28, 2020

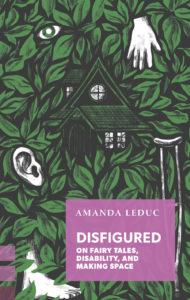

Disfigured, by Amanda Leduc

While I was intrigued by the premise of Amanda Leduc’s Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space, I wasn’t anticipating just how interesting I would find the book, as someone who can get through the day (for now, at least) without giving disability a whole lot of thought and who also didn’t grow up with a strong connection to fairy tales, Disneyfied or otherwise. A few years older than Leduc, I was lucky enough to make it out of childhood without ever longing to be Ariel and before the age when Disney started marketing dresses, so that if I’d ever wanted to dress up as a princess, I would have had to design the costume myself— and that is only part of the reason I never did.

But to say that I did not grow up in a culture steeped in the messages and symbolism of fairy tales, steeped in those stories, would be disingenuous, as Leduc makes clear in Disfigured. Because these stories are everywhere, and yes, they’re only stories… but they’re not only stories. And throughout those stories are representations of disability—hands and heads chopped off in Grimms’ tales that magically grow back, and dwarfs, and women without voices, and witches with crutches, hideously disfigured beasts, and changelings, plus fairy godmothers who exist to reverse one’s fortune.

Leduc, who has cerebral palsy, uses her own experiences (and the text includes her own childhood medical records) to tell a story of what it means when happily ever after means learning to live with one’s disability, instead of magically overcoming it—and suggests that what must be overcome is society’s ableism instead. Disfigured is gorgeously written, a fascinating blend of memoir, scholarship and cultural commentary, a quick read that’s also packed with stories about fairy tales and disability, as well as questions and curiosities. It’s the kind of book that illuminates the ordinary and points to possibilities for a better kind of world.