September 9, 2020

Field Notes From An Unintentional Birder, by Julia Zarankin

There are book reviews, and then there are those reviews of books a reader has been waiting a decade for, ever since the first time the reviewer met the book’s author and was presented with an essay collection by Anne Fadiman as a hostess gift. My friendship with Julia Zarankin was forged over the essay form—though she also introduced me to Wallace Stegner. We contain multitudes. And I’ve been wanted to read a book by her since our very first conversation—she was so smart, kind and hilarious. She was working on a collection of essays at the time about being multilingual. Had not long ago abandoned academia for a different kind of life, and she’d recently taken up…birding? It still seemed unlikely then, not yet a fundamental part of her identity. And a couple of years after we became friends, I had the privilege of her contributing a beautiful piece to my anthology The M Word, the final essay in the book.

As Julia’s passion for birding grew and grew, and she began to disappear every spring for migration season.

But now her book is here, Field Notes From An Unintentional Birder, which I loved as much as I loved any of Anne Fadiman’s essay collections, which is saying everything. And I began to think, as I was reading this book, that in her field notes on birding, Zarankin had also written field notes on blogging—all about paying attention, being patient and persistent, not fearing making mistakes, feeling the exhilaration of unbridled passion—and then I realized that what the book was was a field guide to life.

What a terrifically woven collection this so, so much more than the sum of its parts, each of which is wholly impressive. Through the lens of birding, Zarankin writes gorgeously about finding herself in her mid-thirties, divorced and having left her career. So what now? And it’s through birding that she finds the answers, to this, and to other questions, including how to stay in love, how to be brave, how to be comfortable in her own skin, to understand her own history as a migratory creature, how to live in the moment, and how to have purpose. How to be.

Those answers, of course, are not straightforward. Seeing birds does not lead to satisfaction, but instead a yearning for more of them. It means reconciling herself to the birds she’s missed, or those she might never see. But she learns too the pleasures of living in the moment, of being instead of always striving (though an urge to birdsplain is one that’s hard to shake).

The book has general appeal because birding, like blogging, is life—but I also love the details for birding life that Zarankin shares with such exuberance. She shows the peculiarities of the avian world, and the people who are part of it, in perfect, vivid detail.

September 9, 2020

Seven, by Farzana Doctor

A remarkable balance is required to create a novel about Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) that is also a pleasure to read, but Farzana Doctor pulls it off with Seven, a book that is also about marriage, family, motherhood, sexuality, and rediscovering one’s self and purpose at mid-life.

Sharifa has left her job as a teacher in New York City, and travels with her husband and daughter to India, her birthplace, where her husband will be working during his sabbatical. Other than homeschooling her daughter, however, Sharifa isn’t sure how she will spend her time in India, until she decides to partake in a research project to learn the story of her great-great-grandfather, a wealthy philanthropist who was married three times—and in his second marriage was possibly divorced?

Her marriage has just gone through a rocky patch, and so restoring that relationship is also in the forefront of Sharifa’s mind, as she becomes reacquainted with her aunts and cousins, and then realizes that her cousin’s online activism against FGM practices in their Muslim community (“khatna”) strikes much closer to home than she’d ever imagined. Turns out this archaic practice might not be talked about, but it still takes place today.

The different threads of this novel are woven powerfully. and culminate in a terrifically moving story, in particular a scene where Sharifa and other members of their community (including Sharifa’s excellent husband) gather together to publicly protest khatna, disrupting a long-held taboo. There are moments where this novel of ideas becomes much more driven by those ideas than the story itself, but I forgave these , because the book was so enveloping, and Sharifa’s awakening as to her own history was poignant and absorbing, ultimately hopeful and galvanizing. I loved having her voice in my head.

I also loved the historical thread of Sharifa’s great-great-grandfather, and its resonance in the contemporary story line, and how it all comes together so satisfying in the end.

But then the very end, oh my gosh, it destroyed me. The hardest, bravest literary choice, considering the world we live in, and how tidy endings make us too comfortable. I liked this book a lot throughout, but the leap Doctor takes in her book’s epilogue is so awesome and necessary, underlining the urgency of her message—and about how the pleasure we might take in reading this book (while we do) is actually far from the point.

August 27, 2020

Want, by Lynn Steger Strong

Lynn Steger Strong’s novel Want is packed with the same narrative tension that propelled one of my favourite books of last year, Helen Phillips’s The Need. Both of them, as is apparent from their titles, about desperate yearnings, longings, cravings, desires. For an escape hatch, for example, from the demands of motherhood, the feeding, rocking, soothing, waiting. For a way out of the trap of anxiety, a detour away from the trappings of modern life.

Want is less overtly weird, however. There is no sci-fi element, intruder in antlers, no parallel world. Or rather, the parallel world is the one that Elisabeth was promised, a child of affluent parents growing up on the 1980s and 1990s, pursuing her goals in academia, her husband leaving his job in the financial sector after the crash in 2008 to find more meaningful work in carpentry. They build a life in New York, underpinned by dreams and ideals, but it all falls to pieces. As the novel begins, they’re declaring bankruptcy, a process that began with medical and dental bills. She teaches one class at the university, and works 9-5 at a high school, one of those private academies of nightmares. She and her husband sleep in a closet in their Brooklyn apartment, and still can barely afford the rent. She awakes every morning at 4:30 to get the run in that’s so essential to her mental health, and in her downtime, she scrolls social media feeds for clues about the life of her former best friend, Sasha.

It’s not a conventional narrative. It builds and builds, but it also doesn’t, it just goes, the way a life does when you have to wake up at 4:30 every morning in a closet, when you work all day, and are up nursing most of the night. When you’re just barely hanging on, the way that Elisabeth and her husband are, and she keeps thinking back on her history with Sasha, the various ways they both betrayed each other. A story line also builds about allegations against another professor at the university, about Elisabeth’s somewhat agonizing relationship with her own mother, how the effects of a mental health breakdown years before linger still. Unremarked upon are her feelings towards her husband and children, and perhaps these are the only sure things she’s got going here. Everything else is shifting, tricky, impossible to navigate.

There is a sinister banality to Elisabeth’s experiences, one that touches on experiences of race, class and privilege, and there is also a murder, one most unconventional plot-wise, and how all the pieces of the story fit together in the end is the question. They kind of don’t—but also this is the point. Why this puzzle? Why these pieces? And what is the way out of the state that we’re in?

I loved this book.

August 26, 2020

Still Summer: Books on the Radio

Listen again to my books picks on CBC Ontario Morning! I come in at 33.00.

August 21, 2020

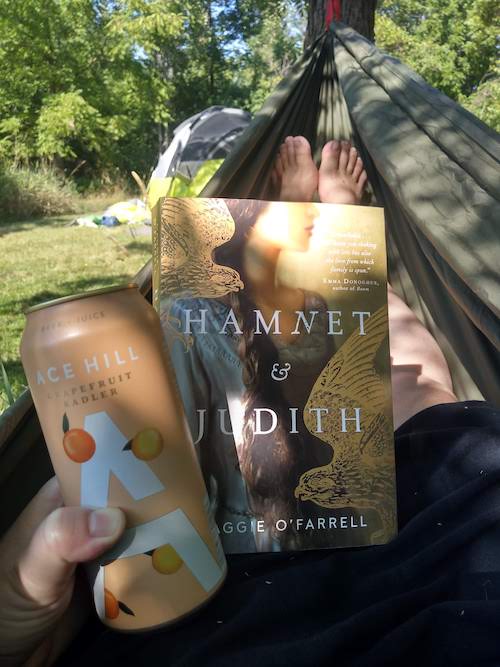

Hamnet and Judith, by Maggie O’Farrell

For YEARS, I have had Maggie O’Farrell confused with the author Catherine O’Flynn, and also I once read another Maggie O’Farrell book (Instructions for a Heatwave) but forgot about it completely, so I wasn’t exactly primed to pick up her latest, Hamnet and Judith, especially since it’s set in the sixteenth century and is about Shakespeare. No thank you.

And yet?

Then I kept reading reviews about it, and I can’t recall exactly what swayed me, but it was something about the universality of the fiction, and the glowingness of all the raves. And so I bought the book when we were at Lighthouse Books last month, and I loved it so completely, reading it a few weeks later when we were camping at Bronte Creek.

Which was two weeks ago now, and this week has got away from me. It is 5:31 pm on a Friday as I write this and I have to go make diner, but first, I want to put down on the record that this is perhaps the finest book you’ll read this year. Oh, the writing! The sentences! The scene in the apple store, those pieces of fruit bop-bop-bopping on the shelves to a rhythm. The whole world so magnificently conjured, and yes, it was the universality. It doesn’t matter that this was Shakespeare’s family (in fact the bard himself is not even named), or the century where the story is set—there was an immediacy to the narrative that I so rarely experience in historical fiction. Perhaps because the story is written in the present tense, but it works, the people, the scenes, so alive, so achingly, complicatedly real. And yes, the heartache, for this is the story of a child who dies, and the family who must suffer this incalculable loss, and this universal. The unfathomability. The fear as well, for this is a story of plague, and it seemed especially resonant as I read it in the summer of 2020. And the chapter about how the plague arrived in Warwickshire, fleas, and beads, and ship cats, the way that one thing leads to another, how everything is connected.

A truly magical, and stunning read.

August 13, 2020

Summer Reading Highlights

Queenie, by Candice Carty Williams

Describing this as a Black Bridget Jones Diary really was to undersell it—no disrespect to Bridget, who I also love. But this is more like Bridget Jones Diary if Bridget was trying to place articles about police murdering Black people. The same bad dates, complicated friendships, career frustrations, but this novel is underlined by a psychological heft that I didn’t see coming and which is powerful. Parts literally brought me to tears, others made me cringe in horror (or recognition). I loved it.

*

Little Secrets, by Jennifer Hillier

This is the second novel I’ve read by Hillier, who has made a name writing dark thrillers, and it’s the first one I feel comfortable recommending in general because no one’s body gets chopped up into tiny pieces. (Yay!) It begins with every parent’s worst nightmare—a child goes missing. But Hillier sets the action a year later when the child’s mother, with nothing left to lose, discovers that her husband is having an affair and decides to seek revenge. If reading about children in peril is too much for you, I promise that this is a different kind of book, twisty and absorbing. I loved it.

*

The Last High, by Daniel Kalla

Another plot-driven highlight is the latest from Daniel Kalla, a Vancouver ER doctor whose work I became more interested in after reading his essay in The Toronto Star about how the pandemic could lead us to greater enlightenment. The novel is set against the opioid crisis, and manages to capture a reader’s attention with a riveting plot, but also tell the real-life story of forces perpetuating devastating drug deaths across the country.

*

Sex and Vanity, by Kevin Kwan

I never read Crazy Rich Asians (I know!) but was intrigued by Kwan’s latest, which re-imagines EM Forster’s A Room With a View. A bit trashy, unabashedly silly, and a lot of fun, I really liked this one, which managed real emotional depth, memorable characters, and a few stunning narrative surprises.

*

Grown-Ups, by Marian Keyes

And I’d never read Marian Keyes either! Why did I wait so long? I was warned that Grown-Ups is NOT her best—it does involve a character who has a head injury that makes her blurt out the truth in a most unsociable manner, which plot-wise is not exactly GENIUS. But the rest of the story (narrative, characters) is so excellently constructed that she pulled it off with aplomb. If you like comedies featuring a whole bunch of family drama, then this one won’t disappoint. And now I want to read everything else she’s ever written .

August 10, 2020

The Vanishing Half, by Brit Bennett

A literary highlight of my week away in July was Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half, the follow up to her smash-hit debut The Mothers, which was one of my favourite books of 2016. A novel that reaches across lines of race, class and gender, across history, across an entire nation…to tell the story of a pair of twin sisters who run away from the southern town they come from, a community of light-skinned Black people. And then years later, in the summer of 1968, one of the sisters returns with her daughter, to live out her life where she started. Ironic when she’s the one who wanted to be an actor, but it’s her twin sister who—as we learn in the rest of the book—spends the rest of her life passing as white, enacting her suburban ennui in an upscale California neighbourhood, like a character in a 1970s’ Joan Didion novel. And what happens when the two sisters’ children become connected years later? Whole lifetimes unfurling from a connection that cannot be severed, a fascinating story of halves and doubleness, infinitely satisfying.

July 22, 2020

The Ghost in the House, by Sara O’Leary

Is there a more charming phantom than Fay, in Sara O’Leary’s The Ghost in the House, who wakes up one day on top of her piano, and realizes she’s haunting her own house? Dressed in her husband’s white shirt, a set of black pearls, and it’s obvious that something is not right. Everything in the house has altered—the atmosphere, the decor. And when she realizes her husband has taken another wife, of course Fay so delicately nudges that woman’s wedding ring off the counter into the sink until it falls down the drain. Because what else would you do in that situation, when your realize your beloved has replaced you with another wife? How would you go about spending your days?

It’s such an interesting premise, but O’Leary makes something substantial, surprising and lovely with it. The narrative itself a bit ghostly, walking through walls, a short book whose chapters and sections leap easily between past and present. There is some mischief, naturally, but the story really gets going when Fay’s husband begins to sense her presence, to see her. After five years of grief, she has come back to him—but he loves hs new wife too. Where do allegiances lie? And there is no right or wrong answer to the question.

The Ghost in the House resonates because Fay herself is so achingly human, yearning for impossible things, and as readers, we can empathize with her supernatural predicament. What would you do? Which is the happy ending, after all? A ghost story that is actually a love story, and one whose spirit lingers once the last page is turned.

July 22, 2020

Summer Reads on the Radio

What a pleasure to talk about books (and swimming, and books ABOUT swimming!) on CBC Ontario Morning today! If you missed it live, listen again on the podcast—I come in at 28.30.

July 10, 2020

The Hollow Land, by Jane Gardam

Last weekend, I had no idea what to read next, which never happens, because I always have this book or that to read for review, or whatnot. I have a pile of new releases that I am definitely excited about, but these were being saved for my holiday. So what? I picked a few books off my shelf and started them, but none of them took, and then I started reading The Hollow Land, by Jane Gardam, a book that’s been sitting on my TBR stack for a while, which I wasn’t even that excited about because sometimes Jane Gardam is hard work (kind of abstract; wholly worth the effort, but can be daunting; maybe it’s just me?).

The Hollow Land was winner of the Whitbread Book Award when first published in 1982, though the fact that it was a collection of linked stories about two young boys didn’t really grab me in theory. I started reading, however, and was hooked—finding the perfect read when you’ve been floundering is a little bit like that sweet relief of being well after an illness. “This book!” I kept exclaiming. So funny, so biting, so delightful. About a rural family in Cumbria whose grandfather’s farmhouse is let to a family from London who come for vacations, leading to all kinds of cultural intersections and misunderstandings. (It is not entirely unlike Schitt’s Creek, to be honest, especially in that polite fun is poked at everybody, and everybody gets to be human.)

Indeed, a collection of linked stories, but more effective than just a gimmick, and they come together to make the book more than the sum of its parts. We return to Bell and Harry as they grow older, as Harry and his family become familiar with the community, and we meet its eccentric characters. It’s pitch perfect, clever and fun, deft and subtle characterization. Kind of like Stephen Leacock’s Sunshine Sketches if they were 300% times better…

And then in the last story, the whole book shifts into a dystopia, taking place in a 1999 after the end of oil…but not so much as changed for Bell and Harry in Cumbria—they’ve gone back to plowing the fields with horses, that’s all. An interesting thing too to consider the end of oil in a land whose hollowness comes from the fact it was long ago mined for coal. A dystopian future set in a rural idyll where nothing ever changes, where timelessness is its essence. It’s such a strange and unexpected diversion, but makes perfect sense at the same time.

Just as reading the book did for me.