July 3, 2019

Summer Reads on the Radio

I was on CBC Ontario Morning today talking summer book picks. You can listen again on the podcast—I come in at 42.30.

June 26, 2019

Big Sky and The Last Resort

To start with, the Jackson Brodie novels were not my favourite Kate Atkinson, but of course I’d read anything by Kate Atkinson. And while indeed these books were my gateway to detective fiction—it seems unbelievable now that I ever needed one—I always preferred my Kate Atkinson more literary. Reading Behind the Scenes at the Museum was one of the most important literary experiences of my life.

But I also know that for many readers, the Jackson Brodie novels were a gateway to Kate Atkinson altogether, before Life After Life and God in Ruins, which were each a brand new level of success in an already remarkable career. And so there has been considerable excitement around Big Sky, Atkinson’s first Jackson Brodie novel in years. But I was not expecting to fall as hard for this novel as I did.

And I did, oh did I ever, carrying hardback book in my bag with glee and pulling it out at every opportunity. The kind of book that makes you only want to be reading, conjuring an incredibly intricate fictional world that’s just meta enough that you know it’s Kate Atkinson, and with real world ties that make Big Sky a novel that’s important as well as delicious.

In this book, Jackson Brodie stumbles backward into a human trafficking ring that had its origins in pedophile rings made up on 1970s’ high profile entertainers, which is not the stuff of fiction, if you’ve been reading the UK press in the last five years. The links between then and now are part of what the story is out to discover, and Atkinson does fascinating things with plot and time to tie the pieces together, and she is a writer so firmly in command of her story and all its threads, almost as though the threads were reins creating the novel’s momentum, making the story go go go.

Underlining everything in this book—the humour, the pleasure, the characters, Jackson’s ex-wife’s voice that’s now stuck in his head—there is rage, rage at the use and abuse and exploitation of vulnerable girls and women by hideous men, and this is a fiercely and furiously feminist novel that’s intent on justice, which isn’t always on the side of law, because the law has protected too many of these hideous men for too long, and Jackson Brodie is having none of it.

—Although it’s not actually Jackson who breaks the case, as he continues stumbling backward—as is often the case, it’s the women who get things done, not to mention a washed-up drag queen, an emotionally intelligent teen-age boy, and the lyrics to “Let It Go.”

“Let it Go” does not factor in The Last Resort, the latest (and bestselling!) novel by my friend Marissa Stapley, but it’s a novel that fits neatly with Big Sky, which I realized this morning as I was reading the latter at its climax. Both novels are about girls and women who’ve been abused and manipulated by hideous men who know just how to wield their power, until things finally reach a breaking point. The Last Resort is set at a luxury resort in Mexico run by a pair of married celebrity marriage counsellors whose own repressed secrets are beginning to rise to the surface, just as a deadly storm is rolling in, and one thought crystallizes like an icy blast: “They’re never going back (to the patriarchy), the past is in the past.”

Burn it down, blow it up, push the bastard off a cliff./ The women are furious, and they’re not taking any more shit.

Okay, I made that part up, with a little inspiration from Elsa, but I reread The Last Resort last week and found it even more compelling than I did upon my first read, appreciating Stapley’s (I refer to all women authors by their surnames in reviews as a feminist statement, even when those authors are my friends) willingness to complicate, to ask questions about women’s complicity in the abuse of other women, to have her readers sit uncomfortably in that space, and to implicate patriarchal institutions—the church, marriage—in such an unabashedly feminist manner.

Packaging all that up inside a plot that zips along and makes for such a gripping read—what more from a book could you ask for?

June 19, 2019

The Youth of God, by Hassan Ghedi Santur

Hassan Ghedi Santur’s novel, The Youth of God —about a young man of Somali background growing up in Toronto—moves between the perspective of the young man himself, Nuur, and that of high school teacher Mr. Ilmi, who is one of the few staff members at the school who isn’t white and therefore has a better perspective than most on what his radicalized students are up against. And in his student, Nuur, Mr. Ilmi sees incredible promise, the kind of scholar he might liked to have become had he not chosen a safer and more conventional path with teaching. Which is not a path that he finds altogether fulfilling, and the novel follows Mr. Ilmi through his experiences at school and also at home, showing his growing connection to his wife, not long ago arrived from Somalia. Things he suspected about her at the beginning of their relationship turn out to be more complicated and interesting than Mr. Ilmi’s original inferences—and this will be a theme in the novel, the things the characters are wrong about, which is unsettling for the reader who is situated in their points of view.

This is especially the case with Nuur, who is smart and obedient, who defines himself as good against his rebellious older brother (who he still looks up to—it’s complicated). Nuur is a very pious Muslim who dresses in traditional religious clothing, which causes him to stand out and be victimized at school, and also alienates him from his more secular parents, who are fighting their own battles and still struggling as immigrants after twenty years in Canada. Young enough still to belief in certainty and absolutes, Nuur is drawn to his teacher and the possibilities of his future in academia—but at the same time he is attracted to a charismatic Imam at his mosque whose messages underline the supposed purity of Nuur’s worldview, but also might possibly be dangerous.

The duel perspectives of The Youth of God provide a compelling story with great tension and a tragic sense of inevitability. Santur shows the way that racialized youth (and Black men in particular) are often not permitted the second (and third) chances availed to their white peers, and therefore how the consequences of their choices and impulses can be dire, even fatal. He also paints a broader picture of the experiences of the Somali diaspora in Canada, and the challenges and struggles that immigrants to Canada continue to face.

June 12, 2019

Echolocation and Meteorites

Echolocation, by Karen Hofmann

As a fan of Karen Hofmann’s novels (I loved After Alice, and What is Going to Happen Next is a title I’ve been recommending widely) I’ve been looking forward to her short story collection, Echolocation, which was published in April—and it did not disappoint. The stories themselves are wide-ranging in tone and style, as well as in their publication history, if Hofmann’s “Acknowledgements” are any indication—the title story was published in Chatelaine in 1998 (and now I am nostalgic for short fiction in women’s magazines, and women’s magazines in general. But I digress). Stories are written in the first person, third person, and even one in first person plural, which I liked a lot—about a group of colleagues retreating to a cottage after a conference, and it’s an incredibly orchestrated melee. “Echolocation” is a story of miscarriage and marriage. In “Virtue, Prudence, Courage,” two misfit newlyweds turn feral on their wilderness honeymoon. In “The Swift Flight of Data Into the Heart,” a woman’s long-buried secret is beginning to rise to the surface. As in What Is Going to Happen Next, this book is impressive for its broad scope and convincingness at all corners—suburban wives and mothers, middle-aged men, a family of immigrants from Bosnia, an ex-nun, an elderly painter who clings to her independence, and former trumpet player from a travelling band of people with dwarfism, although the narrator was taller than they would have liked, but they needed trumpet players, as all bands do.

Meteorites, by Julie Paul

I was also excited to read the latest by Julie Paul, whose last book was winner of the City of Victoria Butler Book Prize and made the Globe and Mail’s Top 100. Similar to Echolocation, Meteorites is a grab-bag of various delights, whose stories whose concerns include obnoxious step-children, ghosts, teenage friendship, brotherhood, a young daughter’s self-harming, an organist determined to persist after her arm is amputated, and also murder. The settings seem familiar, but something sinister lies at their edges—sometimes surreally so—which is part of what makes these stories such compelling reading.

June 5, 2019

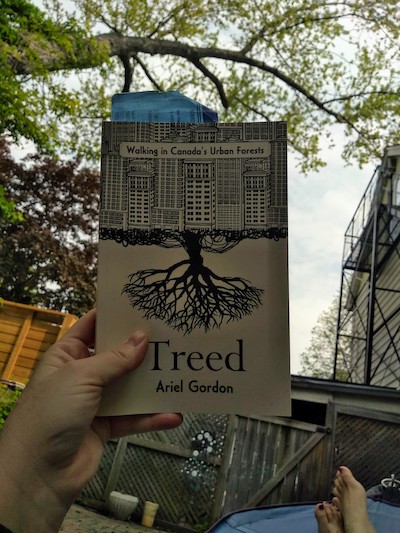

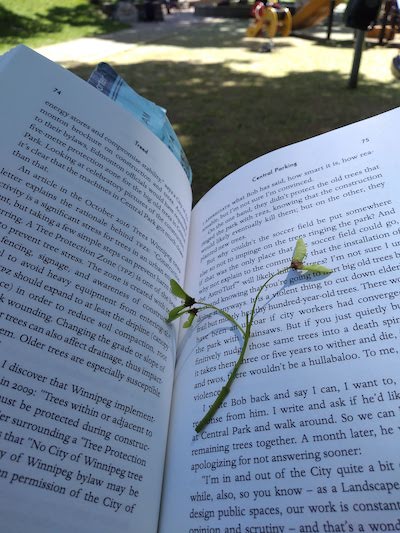

Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests, by Ariel Gordon

Ariel Gordon’s brand new essay collection Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forest, was just the book I needed last weekend, a weekend we headed into amidst news headlines of rising water and forest fires, which I was finding positively dispiriting. And yes, of course, it is supposed to be dispiriting, but I also just can’t live like that, so certain in my despair. I need to still love the world, and find wonder here, and it’s a kind of compulsion, which is what Treed is all about as it makes a kind of sense of the messiness—of hybrid spaces, our history of colonialism, of contradictions, tension and balance, and the absolute insistence of wild things. The very fact of an urban forest.

“But this is a multi-use space. It is a public space. Which means people bring to the forest what they have: Dogs. Children. Inappropriate nudity.”

Treed is also a book about mushrooms, which if you’ve known Gordon online for any length of time is unsurprising, and about the way that mushrooms became her gateway to Winnipeg’s Assiniboine Forest as she began to explore this space which was overwhelming in its immensity, but noticing mushrooms was about detail. And the book’s third essay is a diary of these explorations as Gordon moves through the seasons of the year and of her life, and it acquaints us with the subject, our intrepid narrator, and the space and trees that come to fascinate her.

There are challenges and complexities: balancing urban trees with development, fighting diseases and pests, that trees have a natural lifespan at all, invasive species, monocultures, balancing the needs of people with the trees they live amongst, and Pokemon Go vs. proper exploring (and her cat), and Gordon shows that these complexities are more complicated than she properly understands, a perfect balance impossible, the tension inherent. The challenge of being a living thing on the planet.

I loved this book, which was also about balancing motherhood and writing, the family and the self, solitude and community, city life and the inexorable fact of nature, abject despair indeed and the wonder that is everywhere, if you care to look—starting with the mushrooms.

May 30, 2019

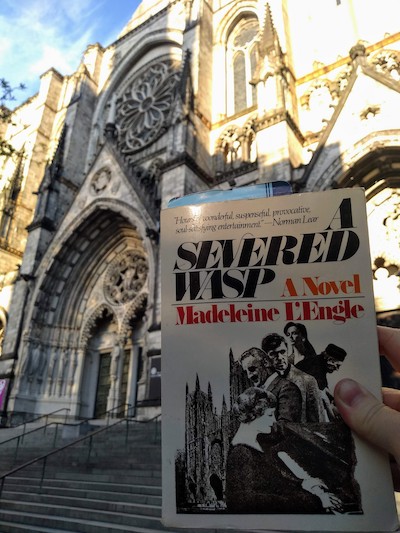

The Severed Wasp, and New York City

Sometimes, one’s inflexibilities rub up against each other in complicated ways, for example: yes, one wants to read Madeleine L’Engle’s lesser known novels in chronological order (ie two more Polly O’Keefe books to go before I read The Small Rain/A Severed Wasp) but also: I really want to read A Severed Wasp during the weekend we’re in New York, because of its setting (which is the same setting for The Young Unicorns, a novel I adored). So what to do? Well. because I am all cool and laidback, I just skipped ahead to be the other books, NBD. Ha ha.

So first to The Small Rain, which was Madeleine L’Engle’s first novel, published in 1945, 37 years and 29 books before its sequel, almost 20 years before L’Engle made her great success with A Wrinkle in Time. And…it was not good. There were interesting tastes of what would come to be L’Engle’s literary preoccupations—it begins with a young girl being cared for by a friend of the family, because her musician parents are unable to be there for her, which reminded me of Maggy in Meet the Austins. There is romance, there is melodrama, there are weird dynamics between teenage girls and grown men, there is a sea voyage. There are weird problems with plot and pacing, and I didn’t really like the book–it read like something terribly old fashioned written by someone who was terribly young and trying to be terribly edgy, and the effect was kind of terrible. I am glad I read it, but I desperately hoped that A Severed Wasp would be very different, but then I supposed it would be, written 37 years and 29 books later. Possibly, L’Engle has learned something about writing novels in the meantime.

A Severed Wasp—published in 1982, and blurbed by no less than Norman Lear!—finds Katherine Forrester in her seventies now, instead of a teenage ingenue. Now widowed and retired after a hugely successful career as a pianist, she has returned to the scene of the previous novel, to New York where she came of age and suffered her first heartbreaks, and she runs into her old friend from Greenwich Village, Felix, who was once a violin-playing beatnik, but now he’s a bishop, which is the way things go in Madeleine L’Engle novels, at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine on New York’s Upper West Side.

Which is a cathedral I first encountered through L’Engle’s The Young Unicorns (1968), the one book in the Austin series that did not feature Vicky at its centre and which was odd, plot-driven, and very compelling. Dave Davidson, who was a teenage boy in the first book, appears again in this one, now grown and Dean of the cathedral, and married to ACTUAL Suzy Austin, who has realized her dream of becoming a doctor, and is also now a mother of four. Interesting because Suzy had been the one who’d always challenged her own mother’s anti-feminism, and I’d wondered about L’Engle’s emphasis on women who had abandoned dreams of career for families, as though the two were impossible to balance. But here was Suzy, doing it all, which Katherine thinks about a lot, because she is conscious of having failed her own children as she’d travelled and toured for much of her daughter’s childhood, and her daughter now remained quite distant from her—in terms of geography and emotion.

But then we will learn that Katherine’s relationship with her daughter is complicated not just for this reason, but also because the daughter was conceived not with Katherine’s husband who’d been castrated at Auschwitz, but by her Nazi prison guard, with whom she’d had a brief affair right after the war. I know, right? The Katherine of The Small Rain has not lost her taste for melodrama, but the stakes have been raised much higher, plus Katherine is receiving obscene phone calls, Felix is also receiving threats to reveal his homosexual affairs, her pregnant downstairs neighbour’s husband has having an affair with a man, the Bishop’s wife is a former pop-singer whose past involvement with drugs continues to haunt her, the streets of New York are dangerous and riddled with crime, and Suzy Austin’s youngest daughter had lost her leg not long ago after being hit by a car in what may or may not have been an accident.

Too much, all of it. Also, too many racist stereotypes—the worst. But the plot did unfold in a most compelling way, and actually being in New York as I was reading made the whole thing much more meaningful to me. (I don’t think many people make A Severed Wasp pilgrimages. There wasn’t even a copy of the book in the Toronto Library system. I had to order a secondhand copy. My instagram hashtag was the only one!) We went to the Cathedral on Friday evening (“The very size of the Cathedral was a surprise…” the book begins. It was!) and got there too late to be able to visit or even explore the grounds, but I just wanted to see it anyway. (Would have been interested to see the plaque that is apparently there once the Cathedral was made a literary landmark because of L’Engle in 2012—she was a writer in residence and librarian there for decades.) We did get to the see the albino peacock in the garden, although the peacocks in the novel seemed to have been conventionally coloured.

We had dinner across the road from the cathedral, and then it was very exciting to be reading the next day and realize that the very place we’d eaten at—the V&T—was described by Suzy Austin was “the best pizza in New York.” It really was! And then the next day we visited other parts of the city, and though I never got to Tenth Street, where Katherine lives in Greenwich Village, we were just close enough that I felt her presence and the streets she’s describing. And the book was in my bag the entire weekend, to be taken out and read on long subway journeys—not that Katherine ever took the subway. I don’t think she even knows it exists.

“Odd, how complex and intertwined life is. Every time I think I’m settling for chance and randomness, then pattern enmeshes me in its strands.”

May 16, 2019

Little Darlings, by Melanie Golding

If domestic noir is still your thing, but you’re finding the genre a little tired (and then some), then pick up Melanie Golding’s debut novel, Little Darlings, which blends the imperilled housewife trope with literary chops and allusions, and hearkens toward the supernatural in the most delicious way.

I read the novel in a single day over Mother’s Day weekend, which seemed entirely appropriate, this book that begins in the delirious aftermath of birth. The birth of twins, no less, and Lauren is shattered, troubled, her husband sent home and she’s left to care for her babies alone, which leaves to a terrifying nocturnal encounter—but is the whole thing just in Lauren’s mind? (And the question I always get stuck on when determining when a woman’s trouble postpartum is in her mind or otherwise—why does the difference even matter, unless you think her mind doesn’t count.)

There’s nothing like the destabilization of new motherhood, how it can reduce one to a vessel, how it realigns marriages and relationships and one’s own sense of self. Golding captures that instability incredibly in this novel as Lauren grows more and more unstable, isolated, and divorced from reality. Or is she? Could it be that Lauren is more perceptive than anyone else around her to the threat she and her sons her facing, a threat that even comes to pass. Or perhaps it does—it’s all unclear. And afterwards, Lauren is convinced that her children are not her own, that they’ve been switched with those belonging to the terrifying “river woman” who is connected to a now flooded village and lore about changelings from centuries ago.

Has Lauren lost her mind? Are the children okay? Is their mother the most real threat they’re facing? And Golding weaves these questions into another storyline involving a police detective who can’t quite let the case go after hearing a recording of Lauren’s emergency call from that night in the hospital. A detective who reminded me of Rachel Bailey from the amazing TV series Scott and Bailey, what with the dysfunctional personal life and disregard for rules and the opinions of her superiors. Turns out this Detective, Jo Harper, gave up her own child born decades before when she was a teenager, and once again the question is whether Harper’s personal experiences are guiding her intuition or whether they’re distracting her from the reality of Lauren’s case. I think we all know what the answer is…

But we don’t entirely, which I appreciate, the way that Golding complicates her story in a way that might prove frustrating to some readers who are hoping for straightforward resolutions, but the author is giving us more than that. She’s giving us problems to think on, sexist biases to consider, and also a dark and creepy story designed to unsettle.

May 16, 2019

The Arm of the Starfish and Dragons in the Water

I think it’s been about ten minutes since I last wrote an ecstatic blog post about how my decision to read Madeleine L’Engle’s Austins series was completely the best thing I’ve done in 2019; so we’re due, right? I finished up the Austin books with Troubling a Star about a month ago, and then decided to embark upon the Polly O’Keefe books, which sort of bridge the Austin and Wrinkle in Time Series. I’d tried to read An Acceptable Time as part of the Wrinkle series when I was a child, but I don’t think I finished it, and I can understand now why it might not have appealed to me, because maybe all these books are best understood in the wider context of L’Engle’s fictional universe(s).

Which is the most amazing mind-bending, time-bending universe. When I picked up Arm of the Starfish, I was actually travelling back in time myself from 1994 (when Troubling a Star was published) to 1964, when she published Arm… (I still can’t believe that this book, which includes a grown-up Meg Murry, now a rather innocuous “Mrs. O’Keefe, was written before A Swiftly Tilting Planet. The way that L’Engle wrote her books so far from the chronological order in which they can be understood to be connected to each other…) Which means that while it was remarkable to reading a novel set just before the summer depicted in A Ring of Endless Night, I was also reading a book by a less sophisticated and practiced novelist. The Arm of the Starfish was also the novel with which L’Engle followed up the smash hit A Wrinkle in Time, which no doubt was some kind of pressure.

The book was okay—it was plot driven and interesting and had all the same kinds of thematic concerns of L’Engle’s work (the nature of good and evil and how they’re connected), but it was lacking in depth and was a bit too action packed. I also found Adam Eddington a less compelling narrator than Vicky Austin, and indeed Meg Murry has not grown into a very interesting woman and my goodness, she is has more children than the Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe. But also, we’re seeing her through Adam Eddington’s eyes and teenage boys are perhaps not the greatest at seeing the marvellousness of a middle aged woman, especially when she is dripping with children. Interesting how Poly swimming with dolphins portends what happens with Vicky Austin not long after—and also I enjoy contemplating what might happen if Poly and Vicky ever met—would the universe explode?

So I wasn’t especially geared up for Dragons in the Water, published in 1976, about a boy called Simon who is on a nautical voyage to Venezuela and meets Poly (who has not yet become “Polly”) and Charles (who is Charles Wallace redux) on board, and together they have to solve a murder and also there are smugglers and art thieves. But I loved it! Simon was a great character (but then again, name a fictional orphan who isn’t) who has been raised to revere an ancestor whose story turns out to be more complicated and troubling than Simon knew. We also get a glimpse of “Mrs. O’Keefe” near the beginning of this book, and she’s a more interesting character than in the previous book.

It was also exciting to meet Mr. Theo who is travelling to hear a concert by Emily, and I met both of these characters first in The Young Unicorns (published in 1969), along with Canon Tallis, who was also in Arm of the Starfish. I love that if we tried to map out a timeline of all these books and universes and how it all fits together, my brain would turn into silly string.

As with the Austin series, the novel is informed by the time it was written in: “I know a lot of politicians nowadays, and even presidents, don’t take promises seriously and even lie under oath, but I was brought up to speak the truth,” says Simon, post-Watergate. I also read this book right after reading an article in The Guardian on a small town in Louisiana that’s one of the most toxic places to live in America because of contamination from a chemical plant, and this scenario is the same as in the novel, which is why Dr. O’Keefe has been called to Venezuela because fish are dying in a lake there where companies are drilling for oil. “Miss Leonis looked down at her feet where black sludge oozed heavily out of the lake. ‘It looks to me as though the oil industry is raping the lake….'”

And then the response: “One thing I have learned in three years at Port of Dragons is that there are no easy solutions.”

And isn’t that the truth.

May 13, 2019

Spring, by Ali Smith

I wasn’t so much addicted to the spectacle as to the ongoing certainty that the next click, the next link, would bring clarity. I felt like if I watched everything, if I read every last conspiracy theory and threaded tweet, the reward would be illumination. I would finally be able to understand not just what was happening but what it meant and what consequences it would have. But there was never a definitive conclusion. I’d taken up residence in a hothouse for paranoia, a factory manufacturing speculation and mistrust.

Olivia Laing, “I was hooked and my drug was Twitter”

I don’t always love Ali Smith’s work (How to be Both did not do it for me) but I cannot overstate what the books in her seasonal quartet have meant to me since the world descended into Worst Possible Timeline, which I date to June 16, 2016, the day that British MP Jo Cox was murdered outside her constituency office by a man who shouted, “Britain First.”

What is going on here, I remember asking myself in horror (except with more expletives) and then again a week later when the Brexit verdict was delivered, and six months after that when Hillary Clinton did not become the first woman President of the United States, and then basically about every ten minutes ever since then. Clinging to Twitter, as Olivia Laing describes in her essay, to make some kind of sense out of this real time nightmare—but then again if there was any sense to be made of it, Twitter would not deliver, because it’s in their interest to keep me refreshing my timeline, to have me yearning for clarity and illumination but never actually delivering.

But then in the Spring on 2017, Autumn arrived, the first book in Ali Smith quartet, set just six months before I was reading it, which is a remarkable turnaround in the world of publishing. And the books in this series are the closest I’ve ever come to the clarity and illumination that Laing is seeking in her essay, the clarity and illumination that I’ve been craving ever since I started to realize that the world is a vastly different place than I’d supposed it was. Even though it’s not so clear or altogether illuminating, but still—that Smith is fashioning art and story out of these times that we’re living in. I get comfort from that. A lazy kind of comfort, possibly, and her novel Winter—published in January 2018 (I walked through a blizzard to get it)—alludes to this. That turning these events into literature puts then at a distance that makes me feel better, and maybe I don’t deserve to. Look, here’s art. These things are cyclic. It will be fine.

It’s not fine, and I know it’s not fine, but I am still roused at Smith’s ability to articulate our situation in her novels. Spring came out this month and begins with four pages of run-on text that appears to be cribbed from Twitter. “We need the dark web algorithms social media. We need to say we’re doing it for free speech.” And then the story begins with a screenwriter who is mourning the death of an old friend who was briefly his lover and who was also his mentor. (What is going on here?) He’s on a train platform in the north of Scotland, and he’s mostly lost in nostalgia, and the train doesn’t come.

In the next section, more disturbing zeitgeist (“We want you to know how much your face means to us. We want your face and the faces of everyone you photograph and the faces of all your friends and the faces of the people they photograph recorded online for our fun data archive and research…”) and then a young woman called Brittany Hall who works as a guard in a detention facility for asylum seekers and/or illegal immigrants—but something strange is afoot. A young girl who managed to get through the barricades, past the guards, inside locked doors and into an office where she convinced the powers that be to have the facility professionally cleaned. Which is to say that it no longer smells like shit in this place where actual people live anymore, even though Brittany Hall has forgotten these are people, because you have to forget, or else how can you bear it. And Brittany Hall is going to end up with this girl on a train to the north of Scotland where they’re going to cross paths with the screenwriter, and like the other two books in the series, this is a novel about art, and the nature or art, and the purpose of art. About hope (springs eternal), because what is art but hope embodied after all.

May 7, 2019

New Lane Winslow Alert

Has it only been a year since I fell in love with Lane Winslow and Iona Whishaw’s wonderful series about the best lady sleuth since Harriet Vane? Set in the interior of British Columbia during the post-WW2, these novels about a young woman who just happens to be an ex-spy—and who would like to retire for a little peace and quiet, please, in the idyllic hamlet of King’s Cove—are as smart and feminist as they are charming, which is saying something. And their underlying messages are so timely and relevant still decades after the time in which the series is set.

My Lane Winslow career started with the fourth book (which was amazing!), and then I spent last summer getting caught up on the back story, just in time for Book Five to come out in the fall. And now Book Six is here, A Deceptive Devotion, as Lane and Inspector Darling plan their wedding (swoon) but (naturally) they stumble upon a murder (the murder rate per capita in King’s Cove rivals that of Midsomer) and things get complicated…

I had the pleasure of providing an endorsement for this book, which I read back in December. “It’s always a pleasure to return to King’s Cove and be swept away by another Lane Winslow tale. This latest instalment—rich with intrigue, humour, murder and romance—underlines why Whishaw’s books have fast become my favourite mystery series.”