May 27, 2021

My Spring Obsession: Katherine Heiny

It started in February when I signed up for an online event celebrating Laurie Colwin, whose book Happy All The Time was appearing in a new edition with a foreword by Katherine Heiny. Heiny was also co-hosting the event, which was a pleasure to “attend” and there was a reference to her work being more than a little Colwin-esque. So I ordered her first novel Standard Deviation from the library. And I loved it. I loved it SO MUCH. I loved it in a where-have-you-been-all-my-life, I-ought-to-recommend-this-book-to-everybody-I-know kind of sense. It was the book that my husband demanded he would get to read right after I was finished with it, because he wanted to know what all the laughing was about, and then I got to listen to him laughing about it too.

Standard Deviation, like Nora Ephron’s Heartburn, like everything by Colwin, is a comic novel that break all the rules of novel-writing and is definitely the kind of book in which nothing much happens and yet everything does. Stories that fixate on minutiae and room decor and thread counts, and everybody is more than a little bit neurotic. Standard Deviation is a novel narrated by Graham, who is married to Audra, his second wife, who never stops talking and is on intimate terms with everybody they encounter. They have a son with Aspergers whose struggles are depicted poignantly but also hilariously—and what a balance is that. This is the most true-to-love depiction of the heartaches of parental love that I’ve ever encountered in a book, and it’s just the most remarkable combination of thoroughly absurd and utterly mundane. I could have read this book forever, Graham as a straight man casting Audra in the most compelling light, though he’s having his own complicated experience as he has a run-in with his first wife, Elspeth, on whom who cheated with Audra, and Elspeth is Audra’s polar opposite in every single way, and because Audra is Audra, she insists that they all get together, and (shockingly) it all doesn’t run so smoothly. Add to the mix their son Matthew’s origami club and its ensuing drama, and you’ve got a family comedy like nothing else you’ve read before…except maybe in Laurie Colwin.

I think maybe if I hadn’t had my mind blown by Standard Deviation, I would have been more ecstatic about her just-released novel Early Morning Riser, which has the same tone as the first novel but is perhaps lacking its tartness. The secondary characters aren’t as realized in this novel, and we encounter them at the beginning of their connection instead of in the midst of a long history which renders the story a little more shallow. Taking place over two decades too instead of the very focused narrative of Standard Deviation, it’s just too sprawling and meandering in terms of plot. But I still really enjoyed it, and bought a copy for my daughter’s Grade 2 teacher because Jane, the main character in the book, is a Grade 2 teacher, who rolls into town and finds love with Duncan, who’s a great guy but, unfortunately (and maybe consequently) has been intimately involved with every woman they encounter in their life together, which makes things a bit awkward for Jane, plus he has his own first wife, and other connections make their life together unnecessarily complicated and Jane is just not sure how she feels about having her domestic life be so crowded…

It was not a great novel by traditional standards, but it was a good novel, and that it was distinctly a Katherine Heiny novel—in terms of humour, character, description—made it a novel that’s thoroughly worth reading. Every since I read her books, my own fiction has included characters who are just a little less ordinary, prone to rashes and strange outbursts. Somebody will be walking into a room, and why not decide that they’re carrying a giant sombrero, you know? It’s a wonderful, inspiring kind of license, to write characters who are outside the ordinary, and I’m really enjoying playing with that.

And I’m also looking forward to finally reading her very first book, the short story collection Single, Carefree, Mellow, whose title story I’m most intrigued by and which I never would have picked up every because these are three adjectives that describe somebody so different from me that I feel like store alarms might go off if I tried to buy it. But I am going to buy it now, because I’m most certain that Katherine Heiny’s writing is meant for me.

May 13, 2021

The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym, by Paula Byrne

I…don’t like big books. They’re heavy to hold, don’t fit in my purse, and I’ve just got no time for that, for the most part. It just doesn’t groove with the pace of my life, and so at 612 pages, I was intimidated by The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym, Paula Byrne’s biography of novelist, the first since a 1990 biography by Pym’s friend and literary executor Hazel Holt which might have revealed fewer insights that it could have out of respect for Pym herself, who’d died of cancer in 1980.

But reader, I read it in two days. Granted, these were two days I’d set aside especially for it, turning off my wifi and accompanying social media so all my attention could be focussed on the task at hand, which was giving my poor wrists the support they needed to hold Byrne’s biography up to my eyes. But it helped that Byrne had divided her book into short and action-packed chapters in the style of 18th century novels like Moll Flanders, chapters with titles such as “In which our Heroine is born in Oswestry,” “In which Miss Pym returns to Oxford,” and so on to “In which our Heroine goes to Germany for the third time and sleeps with her Nazi.”

TURN BACK, BARBARA! was what the residents of my household took to shouting as I kept them abreast of developments in the narrative, such as when Barbara was having an affair with her friend’s father, various gay men, her roommate’s estranged husband, and yes, a literal Nazi. Barbara Pym was an extraordinary person, a brilliant novelist, and had comically terrible judgment when it came to men (and 1930s’ political regimes). Although it occurs to me that her terrible judgment may have been what made her such a wonderful novelist, her ability to imagine her characters into the impossible situations she’d often encountered herself. She took the tragedies (and absurdities) of her own life and spun them into literary (and comic) gold.

Barbara Pym was a fascinating woman—a student at Oxford in the 1930s, she was an enthusiastic participant in sexual relationships, and imagined herself into all kinds of romantic dramas, her particular obsession with one lover occupying her for the rest of her life. She was very drawn to Germany in the 1930s, displaying that typical judgment I’ve always mentioned, but this did not persist into wartime, where she would serve with the WRENs in Naples. After the war, she was hired as an editor for an academic journal in anthropology, which served as fodder for her work (oh my gosh, her treatment of office dynamics and whose job it is to put the kettle on and how is SO SPOT ON) but also paid her a pittance. Being a novelist was most fundamental to her identity out of everything else she did—her first novel, Some Tame Gazelle, was published in 1950. She’d been working on the novel since her Oxford days.

Throughout the 1950s, she published five books, her sixth appearing in 1961. And after this, her new work was not accepted by her publisher, nor by any another. The fashions were changing, and so was the publishing industry (everyone thought the industry was just as dire then as they have ever since), and Pym’s understated humour and wry old-fashioned sensibility had not kept up to date, it was said. So she would toil in the wilderness, encouraged by her excellent friend Philip Larkin, and these years were hard ones for her—money was a struggle, she was depressed by romantic relationships that didn’t pan out, she encountered health struggles, and felt left behind by the literary scene.

And then everything turned around—in 1977, Pym was mentioned (twice!) in a Times Literary Supplement list of underrated writers. All of a sudden, the newspapers and radio were calling. Her publisher wanted to put her back into print, she relished in rejecting them this time, new works coming out with MacMillan, her earlier books re-released. Her next novel, Quartet in Autumn, was nominated for the Booker Prize. Pym would be celebrated before her death at the age of 66, which gives this life the happy ending her biography’s reader longs for. The kind of triumph that doesn’t always happen in life itself, and seems more fitting for a novel instead (but then we’d call the conclusion a little bit pat).

Byrne refreshes one’s perception of Pym in this biography, whose title and form is entirely suited to a life that wasn’t quiet at all, and which pushed the margins in all kinds of ways. She also shows the way that Pym’s work was a reflection of its times, and changed along with the fashions, responding to the world around her, even though many of her preoccupations (spinsters and curates especially) remained the same.

May 10, 2021

Big Reader, by Susan Olding

Susan Olding’s essay collection, Big Reader, is a bibliophile’s delight. The follow-up to her 2008 collection Pathologies affirms should be on the radar of all book-loving people whose hearts skip a beat at the sight of Natalie Olsen’s marbled cover art, a riff on vintage endpapers. But then of course if you look closely, you will notice that the design is less abstract than it first appears, and the marble is a river, and leaves are floating on its surface, and a leaf can be the page of a book or something growing on a tree, to be gathered with a rake when it eventually flutters to the ground, and there’s even an essay on rakes, as in the garden tool and the 18-century series of engravings by William Hogarth “A Rake’s Progress.” Mutability is a theme of, well, life itself, as Olding’s collection attests.

She writes about Anna Karenina and her own affair in a fabulous essay on rereading. She reflects on infertility at Keats’ house. (I just finished reading Barbara Pym’s new biography, which also includes a scene at Keats’ house, a tragic scene in which Pym occurs in a cameo role in one of her novels. It seems like no one has a lot of fun at Keats’ house.) Fairy tail tropes and stepmothering in her essay “Wicked,” which first appeared in the essay collection The M Word, which I edited in 2014. Inspired by Woolf, she writes of “Library Haunting.” On how her mother’s reading life changed as the result of her vision loss. About reading The Golden Notebook on a resort vacation to Hawaii, kind of incongruous. In “Another Writers Beginnings,” which is a response to Eudora Welty and seems in conversation (or at least keeping rhythm) with Joan Didion circa Slouching Toward Babylon, Olding writes a take on self-doubt that I found against the grain of our current moment and also absolutely refreshing—that our self-doubt can serve us as writers. Who would we be without it?

I’d read in a previous review that Oldings essays on Toronto during the AIDs crisis (and the Don River) and another on blood types seem incongruous with the collection’s theme of books and reading, but they actually worked for me, for the way that Olding reads the landscape like a story in the former, and the body in the latter, always searching for signs. She writes about working at a bookstore in downtown Toronto, and how she used to read at the counter, and the oversized atlas kept getting stolen on her watch. Throughout the whole book, she writes about a refusal to conform, to fall into line, to veer into the unexpected, to be one thing and then quite another. “I needed to wander. I wanted to follow a string of words.”

May 7, 2021

Speak, Silence, by Kim Echlin

It’s a difficult sell, Kim Echlin’s novel Speak, Silence, about the International Criminal Court Trials after the Yugoslavian wars that for the first time prosecuted rape during wartime as a crime against humanity. I will admit that I might not have picked it up were I not given the opportunity to interview Echlin for a live book event this week, but am I ever glad I did. The rare kind of novel that has been engaged the way of nonfiction, pausing in my reading to leap down internet rabbit holes and learn about parts of history of which I’d had absolutely no idea (the history of how Bosnians became predominantly Muslim—it’s fascinating!) and I kept turning to my husband and asking myself, “Did you know….?”

Unfortunately the question usually ended with a detail like, “that women were kept imprisoned, raped and tortured, and intentionally made pregnant with genocide as the desired outcome?” Most of that is not explicitly in the book, but instead what I came to understand as I perused internet articles on what happened in Foca, and Bosnia, and all these things that were going on in the backdrop to my life in the 1990s, subjects of television reports. The kind of thing that happens “over there.” How did I never know about this? And Echlin’s novel is both an echo and an answer to that question.

Speak, Silence is a fascinating companion read to Miriam Toews’ Women Talking, a book about violence against women in which the violence is not gratuitous and indeed far from the point, which instead is agency and storytelling, and the power of listening and also being heard. There is a strange tension through Echlin’s text that is suggested by its title, a sense of both-ness. An irreconcilability. That nothing can change or fix what was done to these women and the pain and suffering they live with, and that a criminal trial is still an inadequate way to address their experiences, and yet it’s also everything. That testifying can reopen a woman to pain of her experience, but also permits her a kind of power. That these women who are brave enough to tell their stories, overcoming shame and stigma in order to do so, are finally permitted the power of shape the narrative of women and war, one that has centered on men since the time of The Iliad. Echlin writes about the granite memorials to war dead in the former Yugoslavia, and really everywhere. But nowhere do we find memorials to what happened to these women, and so many women before them.

But the trial itself is a memorial, and Speak, Silence builds upon the trial to further bring these women’s experiences and stories into the consciousness of readers. Echlin choosing to fictionalize the stories, she told me on Tuesday, because it’s through fiction that readers truly get to inhabit another’s experience. And yet there are limits to this too, of course—more of the both-ness I mentioned. The novel is a testament both to empathy and also to its limits. Echlin’s protagonist says, “I did not want to use the word trauma because we all think we know what trauma means but I do not think we do.”

That protagonist, Gota, is a Canadian journalist who has spend the 1990s in Toronto with her small child, the result of a love affair she’d had in Paris with a man from Sarajevo. Uncomfortable with being a mere onlooker via the TV news, Gota travels to Sarajevo to reconnect with him, and meets Edina, the woman he’s always been in love with who is in love with a different man. Edina, a lawyer, has been collecting the stories of women who’d suffered during the war, understanding how these stories could come together to make a case against the perpetrators. And Gota and Edina become connected, Gota wanting to understand what these women had experienced, taking their stories and holding them. She attends the court trials in the Hague, and Echlin outlines the administrative demands of such a thing, the translation and interpretation required for these women to be understood. Gota is determined to learn these women’s stories and write about them, memorialize them, and her character’s intentions are analogous to Echlin’s as she created the novel.

Gota’s daughter stays with Gota’s mother in Toronto, and the reader learns about Gota’s mother’s own past, one touched by war and tragedy, and this story line is a pairing with that of Edina, her daughter, and her own mother, three generations of women, and inter-generational trauma, and resilience, and the heavy price of silence, even when speaking comes with a cost of its own. It’s a curious shape for a novel, just as the love triangle at its centre is also strange, but this is a novel whose shape is more of a web (a net?) than something more linear. There is no such thing as a peripheral character; there is no such thing as periphery at all. Instead, there is connection after connection, bridges being a central symbol in the story (both literal and figurative). The language in the story is so fascinating, subtle and understated, and yet the words themselves are like traps, double edged and tricky.

It’s not a tough book to read—it’s not even long. It’s brutal in a sense, but just as beautiful, Echlin embodying both-ness again by making death-and-violence and undying love both absolutely true at once. Narratively speaking, it’s really curious but fascinatingly so, layer upon layer of meaning, and it’s impossible not to thoroughly engage with, the reader taking the story within and being changed by it, which is just what its author intended.

May 3, 2021

The Girl from Dream City, by Linda Leith

I have become unfathomably bored with the self-mythologization of male writers in my middle years, with all their memoirs and collected works, and stories about all the pretty young women lining up to fuck them. With the takeaway from their examples—that this what a genius is, what an artist is. That these men are the definition of the literary life. Their pompousness, and entitlement to take take up space—but of course, these men are usually compensating for something. If any of them had truly attained the status they believe they are due, wouldn’t they have other people to do the mythologizing for them?

And then along comes Linda Leith’s memoir The Girl From Dream City like the tall glass of water I didn’t even realize I was thirsty for. I loved this book. A book that Leith claims in the end is not a memoir, but more of an essay: “an attempt at approximating what really happened. A prose work, certainly. It has an uncertain basis in what really happened to someone who resembles this girl, the adolescent, the young woman, the older woman—all the characters I might have been, once upon a time.”

In The Girl From Dream City (the title taken from a remark by Pauline Kael about Carey Grant, referenced in Zadie Smith’s essay “Speaking in Tongues”), Leith writes about her extraordinarily peripatetic childhood—born in Northern Ireland, and then to London where her parents are ardent Communists until Leith’s father Desmond, a doctor, travels to Romania and becomes disillusioned with the realities of the movement, then they’re off to Switzerland, and then Montreal, and then Nairobi—but by that time, Leith is making her own way, studying in London, and then returning to Montreal where her literary life is rooted as she becomes a critic, literary magazine editor, novelist, and then founder of the Blue Metropolis Literary Festival, before creating her eponymous publishing company, continuing her celebration of translation, international writers, and really great books.

I love the audacity of a woman naming her company after herself, and that same audacity is so admirably present in Leith’s memoir, of claiming her triumphs and achievements, though this is a kind of audacity that was a long time coming, as she shows in the book. For while she grew up within a culture of storytelling, Leith herself was not encouraged in this respect, expected to submit to her father’s dominant narrative instead instead, and what he expected of his daughter (which was certainly not independence or any kind of challenge). “Whatever you say, say nothing,” from Seamus Heaney, is the epigraph to her first chapter, and this was also her parents approach to their own stories (particularly those of her father’s mental illness and exile from Communism). A lot of this beautiful book is Leith finally fitting together the pieces of the universe that took a long time to make sense to her.

I also love this book for showing that a vibrant domestic life is not necessarily opposed to a literary one. Leith marries young and has three sons, and during the years her life is consumed by her family’s needs (as she was also working as a teacher), she longs to write, and is not able to. And yet all this would become part of her process too—it reminds me of what Carol Shields writes in the afterword to Dropped Threads: “Tempus did not fugit. In a long and healthy life, which is what most of us have, there is plenty of time… This was not a mountain we were climbing; it was closer to being a novel with a series of chapters.” And full immersion in the literary world, in such a fabulous fashion, would be the chapter that—for Leith—arrives when her children are older, an excellent and fulfilling period that continues, bringing together the various threads of her life—travel, languages, literature, books.

Leith writes vividly about the longing she had for this kind of life as both a child, and as a young mother, dreaming of writing books and fabulous conversations with literary people. And in her memoir, she writes just as compellingly about how she made it so, and the books and writers her inspired her, about the trials and errors, successes and triumphs of her career. That this is what an artist is. That this is what constitutes a literary life, and it really is still subversive for a woman to stand up and assert such a thing for herself. To so fully own her story, and to dare to write her name on things, and it’s only subversive, of course, because self-mythologization is not something women are encouraged in—even when it’s most deserved.

Because what is self-mythologizing after all except telling the story of how one came to be?

In The Girl From Dream City, Linda Leith shows us the way.

April 29, 2021

Lost Immunity, by Daniel Kalla

No one really needs to be reading about disease outbreaks during Year 2 of a Global Pandemic, you might argue, but I think you’d be wrong, because Daniel Kalla’s thriller Lost Immunity is about a different disease (meningitis) and because it honestly warmed my heart to come across the book’s references to Covid-19 in the past tense. And because while the book is a compelling plot-driven ride, the ideas it engages with are also timely and vital, and informed by Kalla’s own experiences as an emergency physician in Vancouver BC.

Kalla’s last book, The Last High, about the opioid crisis, was one of my favourite reads of last summer, and the follow-up is even better, mostly because it deals in ideas I’m constantly grappling with anyway these days, about risk and trust, vaccines, and disinformation, and how public health officials are meant to manage anything through all that noise. It’s really wonderful to see these ideas in action, to see them complicated and interrogated in a story about their real world stakes.

The centre of the novel is Lisa Dyer, head of Public Health in Seattle when a meningitis outbreak at a bible camp begins to spread through the community, killing children and teens. Turns out a pharmaceutical company has a new vaccine that’s been through trials and might be the only weapon to stop more people from dying—but she’ll get pushback from the “vaccine-hesitant” community, never mind the fact that both she and the drug company will both have to put their reputations on the line.

But of course because this is a thriller, there is a further complication—someone is trying to sabotage the vaccination program. This aspect of the story heightens the stakes, and underlines the importance of trust and safety, while not undermining the science of vaccination, of which Kalla is well aware. But he also manages sympathetic representation of different points of view—Lisa’s family is opposed to vaccination, and another character is a public anti-vaxxer who blames vaccinations for his son’s autism. Kalla shows that even when the science is sound, the situation on the ground can be complicated, and assessing notions of risk is different in practice than theory, and especially when it’s personal.

I loved this book. A gripping read, but it made me think, which is a perfect combination.

April 19, 2021

Tainna, by Norma Dunning

Almost four years ago, I had my mind blown by Norma Dunning’s short story collection Annie Muktuk and Other Stories, a collection of heartfelt, page-bursting, ribald gorgeous stories, and as soon as I started reading her follow-up, Tainna, I knew I was in for something just as great. The first story, “Amak,” about two sisters estranged for many years who come together again, even though one of them—the narrator—knows she’s walking into a trap. The way that decades-old traumas continue to be carried, and how they might be understood so differently by two people who experienced it together, and the nuance of that relationship, of that fraught and agonizing love that will always fail to deliver what either party desires from it—oh, Dunning nails it with such acuity. She gets it exactly right, which is what I love about these stories, their straightforwardness, how there is nothing extraneous or elliptical. They’re rich and vivid, and absolutely satisfying, but never trite.

“Kunak” is the story of a homeless man on the streets of Edmonton, Inuk like most of the characters in the collection, whose grandfather has passed on to the spirit world, but watches over him still. In “Eskimo Heaven,” a Priest touches the hand of a deceased member of his congregation and is taken on a journey to learn an appreciation for the culture of the people he lives amongst. A group of women just post middle-age get together on the regular to try to snare a rich man in “Panem et Circenses.” And Annie Muktuk is back in “These Old Bones,” this time from her own point of view, when she leaves the north and her husband after a devastating place and begins to build a new life for herself with assistance from a former foe.

That sounds heavy, doesn’t it? And it is, but the story is just as rich with colour and life as it is devastating. Nothing is ever just one thing in these stories, or stays still long enough to be. These are stories of how trauma is born and turned into stories, which is how these characters (and anybody) comes to understand their experiences. These are stories about character, about how character is formed by resilience and grit, and how survival comes from hands that reach out in the darkness, unseen, and how the people those hands are saving are so often unseen themselves, but Dunning makes them known in her stories, in startling, brilliant clarity.

April 15, 2021

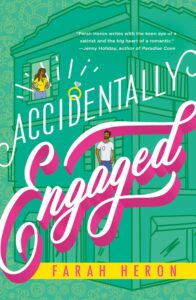

Accidentally Engaged, by Farah Heron

I could not have loved Farah Heron’s sophomore novel Accidentally Engaged any more—I was already besotted by the end of the first paragraph when we first encounter Reena’s sourdough starter, whose name is Brian (obviously). It’s a very pandemicky novel actually, not in content in the slightest, but instead it’s wonderfully cozy, video content is important, and there is so much fresh baked bread. Which is what brings Reena and Nadim together in the first place, the aroma drifting from her apartment across the hall to where he’s just moved in. The attraction between them is instantaneous, but Reena can’t act on it—it turns out her overbearing parents have Nadim in mind as a potential husband for her, and she refuses to let them play this role in her life. And so she and Nadim become friends instead, as well as neighbours. They’re compatible, share the same East African background, and he sure loves her bread. And so when an opportunity comes along for Reena to make her cooking show dreams come true as part of a couples contest, she agrees to let Nadim pretend to be her fiance—but the whole thing is just an act. Or is it?

I loved this novel. Heron’s debut, The Chai Factor, was great, but this follow-up is even better, polished and so deftly plotted. (We also get to meet up with Amira and Duncan again in this book, as Reena is Amira’s best friend.) The humour is spot-on and so very fresh, and the complicated dynamic between Reena and Nadim is drawn out just the right amount, enough to be intriguing, not so much as to be preposterous. There’s a lot of cross-cultural romance going on in fiction right now, with books like The Chai Factor and Jane Igharo’s Ties That Tether, and so it was interesting for me to read a book where both characters come from the same background and even then the course of true love does not run smooth.

Heron challenges conventional notions of Muslim women—they have sex!—and Muslim families once again this second novel, and she writes beautifully about Reena’s pride in her identity as an Indian woman: “Reena loved being Indian. Loved the food, the glittery clothes, and today, she even loved the deep-seated traditions. Like sari shopping with aunties.”

This novel is such a delight.

April 7, 2021

The Relatives, by Camilla Gibb

I loved Camilla Gibb’s new novel, The Relatives, a slim book that reads up fast, but is also not remotely slight. It’s a single volume comprising stories of three different people who don’t know each other—Lila, an alcoholic social worker yearning for a child; Tess, sharing custody of a child after her breakup and disturbed by her ex’s plans regarding their frozen embryos; and then Adam, the American man who’s being held hostage in Somalia. Each of these stories worthy of a novel of its own, and the connections between them are subtle, but important, and the whole arrangement fits together so well, kind of seamlessly, which is a remarkable achievement.

And the seamlessness is the result of the plot and the pacing here, which never stops, and makes this easily a novel you could read in a day. Everything has gone wrong for Lila, who tells her story in first person. She has put her job on the line, overstepping bounds as she brings a young girl into her care who’d been found wandering in Toronto’s High Park and does not speak a word. Lila herself is adopted, never knew the woman who gave her to her, and her own mother has just died, reawakening old wounds but also suggesting new possibilities, and it’s clear that none of this is going to end well, as she tries to fill the hole in her world with the girl.

Adam, in third person, is just as cut off from meaningful ties, even before he’s taken hostage. He’s working for the State Department in Somalia at a refugee camp, undercover, as he investigates rumours of infiltration by militant recruiters…but maybe they’re on to him, and now he’s stuck in a hole, his body brutalized, and the worst of the torture is still before him.

Things are a little less dire for Tess (also first person), an academic who studies isolated islands and other isolated communities, though her personal life is in shambles, something of an island herself. Her ex’s one last chance at motherhood would be by implanting one of Tess’s embryos, but this is a lot of ask of anyone, and especially fraught for someone as prickly as Tess—is it even possible to navigate this situation with any grace?

These stories snowball, compelled by a sense of inevitability, though the specifics still aren’t clear, and this is the seamlessness I’d talking about, how one thing leads to another, and how our lives rub up against those of others, even against our will, and what it is to be related, to have a family, how we write our own stories onto those that belong to other people. Rich and absorbing,The Relatives is about the impossibility of islands, because connection is what humans do, for better or for worse, by accident and on purpose.

March 29, 2021

Summerwater, by Sarah Moss

Dread lurks in Sarah Moss’s Summerwater from the opening pages, from the book’s description on the inside cover, in fact. From the cover itself, which dark and foreboding, and this is such a pandemic novel, though not explicitly. The reference on Page 6 though: “There won’t be a plane this summer, or next. Who could afford to travel now.”—just a little uncanny. It’s a very contemporary novel in its immediacy, in the vein of Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet, but less overtly. There’s a Brexit backdrop though, and it matters a lot, questions of us and them, who belongs and who doesn’t. Set in Scotland, which complicates things even more, at a holiday resort with a handful of cabins nearby a loch, and the weather is dreadful. There is nothing to do but stare out the windows at the unceasing drizzle and also then at the other holidaymakers, each of them mysteries to each other (and to themselves). The skinny mother who insists on going running every morning, the old man who is frustrated by his wife’s increasing infirmity, the young couple on the cusp of a lifetime together, the couple with the little girl and the baby, the grumpy teenagers and their embattled parents, everybody more than faintly annoyed at the people staying in the one cabin—are they Romanian? Ukrainian?—where loud music plays into the night.

Isolation, paranoia, mistrust and frustration colour the various narratives, everybody isolated, far away from WiFi and phone signals. Moving between various dwellers of the resort, each character’s perspective is absorbing and fascinating (and also very funny, moving, illuminating, cringe worthy, etc.) Offering clues that suggest something foreboding, though I never called it right, what actually happened, and it was terrible, but also very satisfying, in the way that devastating conclusions aren’t always—and surprising too, casting the rest of this story in a very different light. Not a spoiler because I am quoting from the cover copy again: “It is the longest day of the year, and as the hours pass imperceptibly, twelve people shift from being strangers, to bystanders, to allies…”

I love a short book, one that can read in a day (especially a day that is rainy). Summerwater is a short novel that will never be called “slight,” and it might be just the thing for a reader finding their pandemic brain is having trouble with focus. I really loved Moss’s previous book, The Ghost Wall, and this one is similar in scope, though also its own creation entirely, and very much recommended.